Summary

We present the results of our approach for treating 12 consecutive cases of acute middle cerebral artery (MCA) stroke by performing balloon-expandable stent (BES) placement after immediate reocclusion due to the underlying stenosis after intra-arterial thrombolysis (IAT).

We retrospectively reviewed the clinical outcomes of 12 patients with acute MCA stroke who underwent recanalization by BES placement in an underlying stenosis after IAT. The time to treatment, urokinase dose, duration of the procedure, recanalization rates and symptomatic hemorrhage were analyzed. Clinical outcome measures were assessed on admission and at discharge (the National Institutes of Health stroke scores [NIHSS]) as well as three months after treatment (modified Rankin scales [mRS]).

The median NIHSS score on admission was 8.6. Four patients received IV rtPA. The median time from symptom onset to IAT was 236 minutes and the median duration of IAT was 62 minutes. The median dose of urokinase was 140,000 units. Initial recanalization after stent deployment (thrombolysis in cerebral ischemia attack grade of II or III) was achieved in all patients. Two patients died in the hospital due to aspiration pneumonia during medical management. In two patients, in-stent reocclusion occurred within 48 hours after stent deployment. At discharge, the median NIHSS score in ten patients (including the patients with reobstruction) was 2.4. The three-month outcome was excellent (mRS, 0-1) in eight patients.

In this study, BES deployment was safe and effective in patients with an immediately reoccluded MCA after successful IAT.

Key words: stroke, stent, atherosclerosis, thrombolysis, middle cerebral artery

Introduction

With an aging population, stroke has become one of the major causes of death and permanent disability in industrialized countries. The most recognized stroke syndromes occur in the middle cerebral artery (MCA) region. In addition to extracranial embolic sources, intracranial atherosclerotic stenosis is considered to be the leading cause of ischemic stroke especially in those of African descent, Asians and Hispanics 1,2. In the United States, intracranial stenosis causes 8% to 10% of all ischemic strokes and the risk of recurrent stroke in these patients may be as high as 15% per year 3-5.

The Wafarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) trial has shown that the overall incidence of stroke due to symptomatic intracranial stenosis is as high as 20% in the first year after the qualifying event, despite standard medical therapy with anti-platelet agents or oral anticoagulants 6. Also, in the case of acute ischemic stroke due to underlying severe atherosclerosis, some studies have reported that immediate reocclusion of the recanalized arteries during performance of intra-arterial thrombolysis (IAT) for acute ischemic stroke was commonly seen or relatively frequently seen, and this was associated with a high grade residual stenosis of the initially perfused arteries 7,8.

Intracranial angioplasty and stenting are evolving as possible treatment options for high-risk patients with symptomatic atherosclerosis. Several studies have reported the feasibility of performing intracranial angioplasty and stent placement for high degree intracranial stenosis 9-12. Also, a limited number of studies showed that intracranial stenting after failed IAT was effective in acute stroke patients 13,14. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been no adequate studies on the specific concerns of reoccluded vessels after successful IAT. Stenting could be a possible treatment option for these cases. Therefore, we evaluated in a retrospective study whether stent placement is a safe salvage therapy if a previously opened MCA in patients with acute stroke was quickly reoccluded due to an underlying stenosis.

Materials and Methods

Between May 2008 and March 2010, all patients with acute ischemic stroke due to obstruction of the MCA and who were referred to our institution for IAT were entered into this study. The institutional review board approved this study and informed written consent was waived. Of these patients, 61 patients with acute obstruction of the MCA were treated with either IAT (47 patients) or combined IV/IA (14 patients) thrombolysis. Of these patients, 48 patients (80.2%) underwent initial recanalization after the IAT (TICI grade II or III). On admission, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was assessed by a stroke neurologist. Either cerebral CT or MR was obtained in all patients before initiation of IA therapy. The inclusion criteria of this study were the following: 1) MCA stroke symptoms with an onset within 6 hours before treatment, 2) CT or MR exclusion of hemorrhage, 3) CT signs of ischemia that affected less than one-third of the MCA territory, and 4) patients with successful initial opening with visualization of acute plaque and subsequent reocclusion of the MCA by intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography (DSA); this was treated by deployment of a BES due to immediate reocclusion after IAT. We excluded patients who were at risk of bleeding (i.e., infarction volume more than one-third of the affected vascular territory), or revealed severe brain edema, intracranial hemorrhage or uncontrolled hypertension. Finally, 12 patients were included in this study. These 12 consecutive patients (average age: 58.3 years, age range: 37-77 years) with acute obstruction of the MCA underwent cerebral revascularization with a combination of a balloon-expandable stent (BES) placement because of immediate reocclusion after IAT.

All patients were examined with CT imaging for evidence of hemorrhage or evidence of early cerebral infarction greater than one third of the distribution of the affected branch. Of these patients, 11 patients were examined with MR imaging, including diffusion-weighted imaging and MR angiography. Perfusion-weighted imaging was not available for one patient at the time of ictus. All 11 patients underwent MR examination that showed diffusion anomaly, a diffusion-perfusion mismatch and MR angiography findings of MCA occlusion.

Two patients who met the standard National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) criteria for receiving intravenous (IV) recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) were treated with 0.9 mg/kg of IV rtPA (Actylase, Boeringer Ingelheim, Germany). Intra-arterial (IA) therapy was performed because there was no neurologic improvement within 1 hour of IV rtPA. All IA therapy was performed by one interventional neuroradiologist. Cerebral angiography was performed via a femoral approach. The beginning of IA therapy was defined as the needle puncture of the common femoral artery. After arterial puncture and insertion of a 7F guiding sheath (Super Arrow Flex; Arrow international, Reading, PA, USA) and 7F guiding catheter (Guider Softip; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA), systemic anticoagulation was maintained with a 3000-U bolus of intravenous heparin followed by 1000 U/h of intravenous heparin. After angiographic evidence of an acute MCA occlusion responsible for the presenting neurologic symptoms was confirmed, the patient underwent IAT with urokinase infusion and mechanical clot disruption with a microcatheter and a microguide wire. An end-hole microcatheter (Microferet; Cook, Bjaeverskov, Denmark) over a microguide wire (Synchro-14, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was advanced through the7F guiding catheter into the MCA occlusion site. We thought that the underlying stenosis of MCA was because of resistance into the MCA during passage of the microcatheter. The microcatheter tip was placed into the thrombus, and then a 100,000 U bolus of urokinase (Green Cross, Yongin, Korea) diluted in 10 mL of saline and contrast medium was manually infused for three to five minutes. Mechanical clot disruption with a microcatheter and a microguided wire was undertaken immediately after 100,000 U of urokinase was administered. Mechanical clot disruption consisted of multiple passes of the microguide wire through the clot after the tip was manually shaped into a complete J-curve that approximated the diameter of the vessel. During this process, the microcatheter was often advanced multiple times over the microguide wire as well. After mechanical clot disruption, 100,000 U bolus of urokinase diluted in 10 mL of saline and contrast medium was manually infused for three to five minutes at the site of the remaining thrombus. The urokinase infusion was stopped immediately if angiograms showed complete recanalization.

The angiograms of all patients after urokinase infusion and mechanical clot disruption showed the continuous antegrade flow and severe stenosis of the MCA. We waited five to ten minutes to confirm whether reobstruction of the MCA occurred. All patients showed a decreased MCA flow and/or reobstruction and then received a bolus dose of abciximab (0.25 mg/kg) through the microcatheter because of the possibility of acute platelet aggregation. Also, we waited five to ten minutes, but the MCA flow did not restore after injection of abciximab. Therefore, we thought that these patients had an underlying stenosis of the MCA combined with thrombus of the distal portion of the MCA because of resistance into the MCA during passage of the microcatheter and no restoration after injection of abciximab. We then placed an intracranial stent at the stenosis to restore MCA flow.

Before stenting, clopidogrel (300 mg) was orally administered through an orally-placed gastric tube to prevent acute stent thrombosis (these patients were not pretreated with adequate antiplatelet medications). For intracranial stenting, an exchange microguide wire (Transend 300 ES Floppy; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was used to exchange the microcatheter. Five patients underwent percutaneous angioplasty for the treatment of MCA stenosis. The balloon diameter was generally 1.25 or 1.5 mm and it was purposely undersized. The angiograms of these patients revealed a decreased MCA flow during the waiting period after percutaneous angioplasty. The BES stent (Flexmater; Abbott, Abbott Park, Michigan, USA) was sized to simulate the diameter of the normal patent vessel. The stent length was selected to be equal to or exceed the length of the target lesion (2.0-2.5 mm diameter, 9-12 mm length). The proximal one third to one half of the stent was positioned at the point of occlusion. As indicated, postdilation of the stent was performed with a balloon sized to 80% of the predicted vessel diameter. Delayed angiographic runs were performed to grade the postprocedural TICI and to rule out thrombosis, spasm or dissection. Patients received a maintenance dose of either aspirin (100 mg daily) or clopidogrel (75 mg daily) the day after the procedure.

Pretreatment and posttreatment angiograms were evaluated by the same interventional neuroradiologist. The recanalization status was classified according to the Thrombolysis in Cerebral Ischemia (TICI) scale (grade 0: no perfusion, grade I: penetration but not perfusion, grade IIa: partial perfusion with incomplete distal filling of <50% of the expected territory, grade IIb: partial perfusion with incomplete distal filling of 50%-99% of the expected territory, grade III: near complete perfusion but with delay in contrast runoff, grade IV: full perfusion with normal filling of distal branches in a normal hemodynamic fashion) 15. Recanalization was defined as TICI grades of II or III.

Age, gender, the NIHSS on admission, time from symptoms to IA therapy, the duration of the procedure, urokinase dose, recanalization, symtomatic intracranial hemorrhage, the NIHSS at discharge and outcomes were recorded and analyzed. Clinical evaluation was done by stroke neurologists who were not blinded to the treatment. A brain CT scan was routinely obtained immediately after the procedure. Also, brain CT and MRI was performed if the patients showed neurologic deterioration during admission. The CT scans were analyzed for hemorrhagic transformation by the same interventional neuroradiologist. Follow-up MRI was performed three months after the procedure. Any new infarct in the ipsilateral area was recorded. Clinical outcomes were assessed by a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) at three months and they were dichotomized as favorable (mRS: 0-2) or unfavorable (mRS: 3-6).

Results

The clinical characteristics of the 12 patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the 12 patients (nine men and three women) was 59.4 years (range, 37-77 years). The median NIHSS score was 8.6 (range, 4-18; SD 3.6) on admission. The median time between the onset of neurologic symptoms (defined as the time preceding which the patient was in his or her usual state of health) and endovascular intervention was 236 minutes (90 to 350 min), and the median duration of IA therapy was 62 minutes (range: 50-75 min). Ten angiographic occlusion sites were located in the MCA and there were two combined lesions of the distal internal carotid artery and MCA.

Table 1.

Clinical and imaging characteristics and outcomes of the 12 patients.

| Patient No./Age (y)/Gender |

NIHSS score on admission |

Onset time (min) |

Time to IA therapy (min) |

Duration of procedure (min) |

Urokinase dose (×104 U) |

Angioplasty (mm) |

Stent (mm) |

TICI grade |

Symptomatic hemorrhage |

NIHSS at discharge |

mRS at 3 Months |

Clinical Outcome |

Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/56/F | 8 | 200 | 240 | 50 | 20 | 1.5 × 15 | 2.5 × 9 | 3 | No | 0 | 0 | HTN | |

| 2/59/F | 6 | 100 | 140 | 65 | 20 | 2.5 × 12 | 3 | No | NA | 6 | Death | HTN | |

| 3/58/M | 4 | 180 | 230 | 50 | 10 | 1.5 × 15 | 2.5 × 12 | 3 | No | 0 | 1 | Alcohol | |

| 4/48/M | 8 | 300 | 340 | 70 | 10 | 2.5 × 9 | 3 | No | 5 | 2 | HTN, Alcohol |

||

| 5/75/F | 18 | 180 | 250 | 65 | 20 | 2.5 × 12 | 2b | Yes | 16 | 6 | Death | HTN | |

| 6/49/M | 5 | 60 | 90 | 50 | 20 | 2.5 × 12 | 3 | No | 2 | 1 | Reob- struction |

HTN, Alcohol, Smoker |

|

| 7/77/M | 8 | 200 | 260 | 70 | 10 | 1.5 × 15 | 2.5 × 12 | 3 | No | 2 | 1 | Smoker, Alcohol |

|

| 8/37/M | 10 | 60 | 90 | 60 | 20 | 2.0 × 15 | 2.5 × 12 | 3 | No | 3 | 3 | Reob- struction |

Smoker |

| 9/58/M | 16 | 300 | 350 | 70 | 10 | 2.5 × 9 | 3 | No | 5 | 3 | No | ||

| 10/60/M | 4 | 180 | 230 | 50 | 10 | 2.5 × 12 | 3 | No | 0 | 1 | Alcohol | ||

| 11/47/M | 8 | 300 | 340 | 70 | 10 | 2.5 × 12 | 3 | No | 5 | 2 | HTN, Alcohol |

||

| 12/78/M | 8 | 200 | 260 | 70 | 10 | 1.5 × 15 | 2.5 × 9 | 3 | No | 2 | 1 | Alcohol | |

| HTN = hypertension | |||||||||||||

All patients underwent IA thrombolysis with urokinase and mechanical clot disruption with a microcatheter and microguide wire. The dose of urokinase was 100,000-200,000 U (median: 141,000 U). After IA thrombolysis and mechanical clot disruption, the angiograms showed the underlying stenosis of MCA at the occlusion site in all patients. Percutaneous angioplasty was performed in five out of 12 patients. These patients had reobstruction of the MCA after ten to 20 minutes.

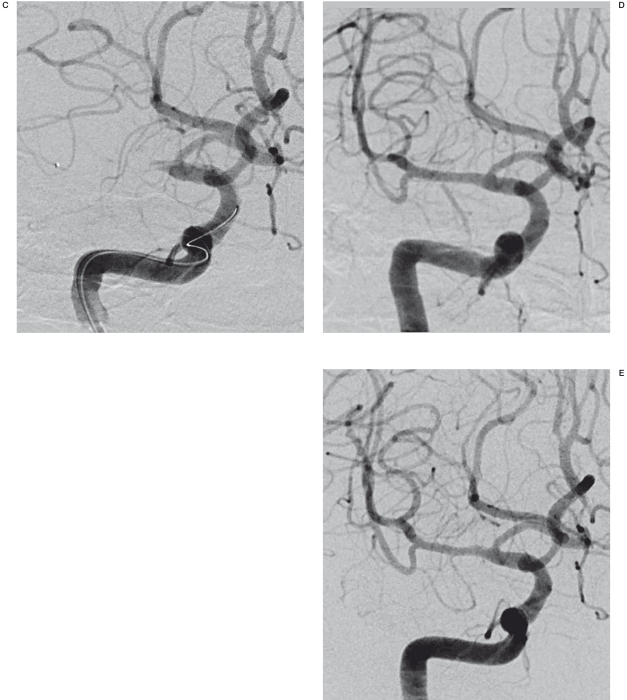

Technical success of intracranial stenting was achieved in all patients. Recanalization (TICI grade II or III) was also observed in all patients. TICI grade III occurred in 11 patients (91.7%) and TICI grade IIb occurred in one patient (8.3%; Figure 1). No procedure-related complications such as vessel rupture or dissection were observed. No acute hemorrhage (either intraparenchymal or subarachnoid) was seen on the postprocedural CT scan obtained within 24 hours of the procedure. One patient had a hemorrhagic transformation in the core area of the infarction seen on MR scan within 72 hours of the procedure. Two in-hospital deaths (16.7%) occurred: one with hemorrhagic transformation due to progression of stroke and withdrawal of care at the family's request and one secondary to respiratory failure due to aspiration pneumonia.

Figure 1.

A 58-year-old man with history of alcohol abuse developed mental changes. A) The initial angiogram in the frontal projection shows complete obstruction of the right middle cerebral artery. B) The angiogram after IA thrombolysis shows the underlying stenosis of the right middle cerebral artery. C) The 20 min-delayed angiogram shows reobstruction of the right middle cerebral artery. D) Post stent-deployment angiography shows good patency. E) The follow-up angiogram after 2 months shows good patency and a normal range of flow.

Two patients underwent early reobstruction due to in-stent reocclusion within 48 hours of the procedure. These patients were heavy smokers. These patients underwent IA therapy including urokinase infusion, mechanical clot disruption with a microcatheter and microguide wire, and angioplasty, but they did not achieve recanalization of the MCA. Of these patients, one patient had bypass surgery performed due to poor collateral flow, and one was treated with conservative treatment due to good collateral flow.

At discharge (10/12), the median NIHSS score was 2.4 (range: 0-5). The NIHSS scores of all patients were improved. For the neurologic improvement, seven of ten patients achieved a ≥4-point reduction of their admission score; three patients achieved a three-point reduction. At the three-month follow-up, the functional outcome was excellent (mRS, 0 or 1) in six (60%) of the ten patients, good (mRS, 2) in one patient and poor (mRS, 3-5) in two patients. No new infarctions were found with follow-up MRIs.

A follow-up study at six months for restenosis was completed in eight patients. Angiographic follow-up in six patients revealed a mean 31 ± 0.23% stenosis. No definite restenosis (>50%) was seen on with CT angiography and Doppler studies, indicating that there was no restenosis in our study patients (0/8).

Discussion

Some studies have reported that immediate reocclusion of recanalized arteries during IAT for acute ischemic stroke was commonly or relatively frequently seen, and this was associated with a high grade residual stenosis of the initially perfused arteries 7,8. Qureshi et al. 7 showed that early reocclusion occurred in eight of 46 patients (17%) with initial recanalization after IAT and a mechanical maneuver. Reocclusion after IAT was associated with poor clinical outcomes. Heo et al. 8 reported that early reocclusion occurred in four of 18 patients (22%) with initial revascularization after IAT or combined IV/IA therapy. This reocclusion occurred in those patients with high-grade residual stenosis of the initially perfused arteries and administration of abciximab achieved effective clot lysis. In our study, reocclusion occurred in 12 of 48 patients (25%). Those patients with early reocclusion after IAT had underlying atherosclerotic stenosis of the MCA.

Mechanical device trials have recently been initiated in the hope of addressing these concerns. Mechanical maneuvers described in the literature have included clot maceration with a microcatheter or microguide wire 16 as well as the use of a thrombectomy device 17-19, stent 20 or balloon angioplasty 21. Yoon et al. 16 reported that techniques using low-dose intra-arterial urokinase and aggressive mechanical clot disruption have markedly improved the recanalization rates. However, angioplasty or/and placement of an intracranial stent must be performed, as in our cases, for the treatment of patients with severe atherosclerotic stenosis and immediate reocclusion after IAT.

Percutaneous angioplasty alone and stent placement for symptomatic intracranial stenosis after use of a microballoon catheter is intended for cerebrovascular use in patients who are refractory to medical management and this also increased the technical success rate; this also increased the interest in these therapeutic options. Connors et al. 9 reported a 16% incidence of significant postoperative residual stenosis after 50 angioplasty procedures. Marks et al. 22 reported a much higher rate of significant postoperative residual stenosis in an intracranial angioplasty series (18/36 cases, 50%). In contrast, Yoon et al. 23 reported a low recurrence rate of ischemic symptoms during long-term follow-up and a low rate of periprocedural complications after intracranial angioplasty in patients with symptomatic MCA stenosis. We thought that these results occurred because of variable causes such as the size of the intracranial balloon, pressure and duration of balloon inflation or the patient's condition. In the present study, we performed intracranial angioplasty for the treatment of reocclusion after IAT, but no patients showed a recanalization of MCA. We thought the low rate of recanalization after intracranial angioplasty was due to small size of the balloon catheter, the low pressure of balloon inflation or a hemodynamically unstable condition.

Intracranial stent placement for recanalization in the setting of acute stroke after failed chemical and/or mechanical IAT has been performed in a limited number of patients 13,14. These previous studies showed that intracranial stenting is associated with a high rate of recanalization and a low rate of intracranial hemorrhage. Siddiq et al. 24 reported that stent treatment for intracranial atherosclerosis had a lower rate of significant postoperative residual stenosis as compared with that of primary angioplasty alone. Our retrospective study shows that BES deployment is safe and effective in patients with immediate reocclusion of the MCA after IAT due to high-grade residual stensosis. No technical failure was encountered in our study. The recanalization (TICI grade II or III) rate after intracranial stent placement in our study was 100%. Suh et al. 25 reported that the procedural success rate of intracranial stenting for severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis was 99%.

Suh et al. 25 reported that the adverse event rate after intracranial stenting of severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis was much lower in the stable patient group (4.1%) compared with that of the unstable patient group (25.9%). The risk of acute stent thrombosis without appropriate antiplatelet therapy has been well documented in the cardiac literature 26,27. Nahab et al. 28 reported that major complications after intracranial stenting were associated with stenting soon after a qualifying event (<10 days) and stroke was the qualifying event. Because of the emergency nature of this procedure in acute stroke patients, a loading dose of aspirin (100 mg orally) and clopidogrel (300 mg orally) at least three hours before the procedure, and a statin (80 mg of atorvastatin) at a mean of 12 hours before the procedure may improve clinical outcome by improving endothelial function. These drugs have vasodilatory effects, direct antithrombotic effects and anti-inflammatory actions. An adjunctive platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor such as tirofiban or abciximab may be used as rescue management for the case of procedure-related thrombosis. In our study, we used a loading dose of clopidogrel (300 mg orally) immediately before the procedure. No patients had procedure-related thrombosis immediately after intracranial stenting. Patients received a maintenance dose of either aspirin (100 mg daily) or clopidogrel (75 mg daily) the day following the procedure. Two patients in our study showed early reobstruction due to plaque aggression or acute thrombus within 48 hours of the procedure, and they failed to achieve recanalization although injection of abciximab was given and additional angioplasty was performed. Therefore, additional randomized controlled studies will be required for more effective management of emergency patients.

Concerning the choice between using a BES or a self-expandable stent (SES), advocates of SES claim that the balloon-mounted stents developed for cardiology are less flexible than the self-expandable stent, and therefore the BES technique was developed to decrease procedural risks as compared with the use of the relatively flexible SES 29. Yue et al. 30 reported that the frequency of restenosis after intracranial stenting in patients with symptomatic stenosis of the MCA was higher in the SES group than the BES group, but there were no differences in clinical outcomes. In our institution, SES could not be used due to the policies of Korean public health insurance. But none of our cases showed procedure-related complications within 24 hours, including arterial dissection, vessel perforation and acute stent thrombosis. Only one patient had hemorrhagic transformation in the core area of the infarction seen on an MR scan within 72 hours of the procedure. In this study, restenosis did not appear during the follow-up period.

One major concern of intracranial stenting is perforator occlusion from the “snow plowing” effect (i.e., forceful displacement of an atheroma in the perforator ostia) attributed to high deployment pressure of the BES 31,32. When BES were the only option for intracranial stenting, a “staged approach” was shown to reduce periprocedural stroke risk 32. It was suggested that intimal fibrosis and vascular remodeling fostered in the interim period might reduce the “snow plowing effect” in subsequent stenting. However, in our study, all patients had MCA occlusion at admission and no new aggravation of perforator infarction was found in follow-up MRI scans. We thought that this result appeared because all patients had the initial infarction of basal ganglia due to MCA occlusion at admission.

The limitations of our study included the lack of central adjudication of the events and cerebral angiograms as well as the lack of a prospective follow-up of the study patients. Further, our results have to be interpreted with caution because of the retrospective nature of the study, the inhomogeneous and small patient cohort and the different therapies used in addition to the placement of an intracranial stent. Finally, we did not obtain data on the patients treated with stents other than coronary stents. These questions are all important to consider in future studies.

Conclusions

Our study showed that BES deployment is safe and effective in patients with immediate reocclusion due to underlying atherosclerotic stenosis after successful IAT. A high rate of recanalization, a low rate of symptomatic hemorrhage and excellent functional outcomes can be achieved in this setting using BES.

References

- 1.Wityk RJ, Lehman D, Klag M, et al. Race and sex differences in the distribution of cerebral atherosclerosis. Stroke. 1996;27:1974–1980. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.11.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldmann E, Daneault N, Kwan E, et al. Chinese-white differences in the distribution of occlusive cerebrovascular disease. Neurology. 1990;40:1541–1544. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.10.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, et al. Race-ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke. 1995;26:14–20. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) Trial Investigators Design, progress and challenges of a double-blind trial of warfarin versus aspirin for symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:106–117. doi: 10.1159/000068744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chimowitz MI, Kokkinos J, Strong J, et al. The Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease Study. Neurology. 1995;45:1488–1493. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.8.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasner SE, Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, et al. Predictors of ischemic stroke in the territory of a symptomatic intracranial arterial stenosis. Circulation. 2006;113:555–563. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.578229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qureshi AI, Siddiqui AM, Kim SH, et al. Reocclusion of recanalized arteries during intra-arterial thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:322–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heo JH, Lee KY, Kim SH, et al. Immediate reocclusion following a successful thrombolysis in acute stroke: a pilot study. Neurology. 2003;60:1684–1687. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063323.23493.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Connors JJ, 3rd, Wojak JC. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for intracranial atherosclerotic lesions: evolution of technique and short-term results. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:415–423. doi: 10.3171/jns.1999.91.3.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bose A, Hartmann M, Henkes H, et al. A novel, self-expanding, nitinol stent in medically refractory intracranial atherosclerotic stenoses: the Wingspan study. Stroke. 2007;38:1531–1537. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.477711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks MP, Wojak JC, Al-Ali F, et al. Angioplasty for symptomatic intracranial stenosis: clinical outcome. Stroke. 2006;37:1016–1020. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000206142.03677.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaidat OO, Klucznik R, Alexander MJ, et al. The NIH registry on use of the Wingspan stent for symptomatic 70-99% intracranial arterial stenosis. Neurology. 2008;70:1518–1524. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000306308.08229.a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy EI, Ecker RD, Horowitz MB, et al. Stent-assisted intracranial recanalization for acute stroke: early results. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:458–463. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000199159.32210.E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sauvageau E, Samuelson RM, Levy EI, et al. middle cerebral artery stenting for acute ischemic stroke after unsuccessful Merci retrieval. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:701–706. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000255419.01302.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noser EA, Shaltoni HM, Hall CE, et al. Aggressive mechanical clot disruption; a safe adjunct to thrombolytic therapy in acute stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:292–296. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000152331.93770.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon W, Park MS, Cho KH. Low-dose intra-arterial urokinase and aggressive mechanical clot disruption for acute ischemic stroke after failure of intravenous thrombolysis. Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31:161–164. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gobin YP, Starkman S, Duckwiler GR, et al. MERCI 1: a phase 1 study of Mechanical Embolus Removal in Cerebral Ischemia. Stroke. 2004;35:2848–2854. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147718.12954.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castao C, Dorado L, Guerrero C, et al. Mechanical thrombectomy with the Solitaire AB device in large artery occlusions of the anterior circulation: a pilot study. Stroke. 2010;41:1836–1840. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penumbra Pivotal Stroke Trial Investigators The penumbra pivotal stroke trial: safety and effectiveness of a new generation of mechanical devices for clot removal in intracranial large vessel occlusive disease. Stroke. 2009;40:2761–2768. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.544957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly ME, Furlan AJ, Fiorella D. Recanalization of an acute middle cerebral artery occlusion using a self-expanding, reconstrainable, intracranial microstent as a temporary endovascular bypass. Stroke. 2008;39:1770–1773. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.506212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakano S, Iseda T, Yoneyama T, et al. Direct percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for acute middle cerebral artery trunk occlusion: an alternative option to intra-arterial thrombolysis. Stroke. 2002;33:2872–2876. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000038985.26269.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marks MP, Marcellus ML, Do HM, et al. Intracranial angioplasty without stenting for symptomatic atherosclerotic stenosis: long-term follow-up. Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:525–530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon W, Seo JJ, Cho KH, et al. Symptomatic middle cerebral artery stenosis treated with intracranial angioplasty: experience in 32 patients. Radiology. 2005;237:620–626. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siddiq F, Vazquez G, Memon MZ, et al. Comparison of primary angioplasty with stent placement for treating symptomatic intracranial atherosclerotic diseases. A multicenter study. Stroke. 2008;39:2505–2510. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.515361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh DC, Kim JK, Chol JW, et al. Intracranial stenting of severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis: results of 100 consecutive patients. Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:781–785. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinhubl SR, Talley JD, Braden GA, et al. Point-of-case measured platelet inhibition correlates with a reduced risk of an adverse cardiac event after percutaenous coronary intervention: results of the GOLD (AU-Assessing Ultegra) multicenter study. Circulation. 2001;103:2572–2578. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.21.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walter DH, Schächinger V, Elsner M, et al. Platelet glycoprotein IIIa polymorphisms and risk of coronary stent thrombosis. Lancet. 1997;350:1217–1219. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)05399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nahab F, Lynn MJ, Kasner SE, et al. Risk factors associated with major cerebrovascular complications after intracranial stenting. Neurology. 2009;72:2014–2019. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0b013e3181a1863c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henkes H, Miloslavski E, Lowens S, et al. Treatment of intracranial atherosclerotic stenoses with balloon dilatation and self-expanding stent deployment (WingSpan) Neuroradiology. 2005;47:222–228. doi: 10.1007/s00234-005-1351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yue X, Yin Q, Xi G, et al. Comparison of BMSs with SES for symptomatic intracranial disease of the middle cerebral artery stenosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:54–60. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9885-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung TW, Yu SC, Lam WW, et al. Would self-expanding stent occlude middle cerebral artery perforators. Stroke. 2009;40:1910–1912. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.532416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levy EI, Chaturvedi S. Perforator stroke following intracranial stenting: A sacrifice for the greater good. Neurology. 2006;66:1803–1804. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000227198.02597.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]