ABSTRACT

To help define the biological functions of nonessential genes of Francisella novicida, we measured the growth of arrayed members of a comprehensive transposon mutant library under a variety of nutrition and stress conditions. Mutant phenotypes were identified for 37% of the genes, corresponding to ten carbon source utilization pathways, nine amino acid- and nucleotide-biosynthetic pathways, ten intrinsic antibiotic resistance traits, and six other stress resistance traits. The greatest surprise of the analysis was the large number of genotype-phenotype relationships that were not predictable from studies of Escherichia coli and other model species. The study identified candidate genes for a missing glycolysis function (phosphofructokinase), an unusual proline-biosynthetic pathway, parallel outer membrane lipid asymmetry maintenance systems, and novel antibiotic resistance functions. The analysis provides an evaluation of annotation predictions, identifies cases in which fundamental processes differ from those in model species, and helps create an empirical foundation for understanding virulence and other complex processes.

IMPORTANCE

The value of genome sequences as foundations for analyzing complex traits in nonmodel organisms is limited by the need to rely almost exclusively on sequence similarities to predict gene functions in annotations. Many genes cannot be assigned functions, and some predictions are incorrect or incomplete. Due to these limitations, genome-scale experimental approaches that test and extend bioinformatics-based predictions are sorely needed. In this study, we describe such an approach based on phenotypic analysis of a comprehensive, sequence-defined transposon mutant library.

Introduction

The value of a genome sequence as a basis for understanding complex activities of an organism depends on the accuracy and completeness of its annotation. Function predictions in genome annotations are based largely on identifying related sequences characterized experimentally in model organisms. While such predictions can be highly informative, sequence relatedness generally identifies molecular activities much better than biological functions (1, 2). The fraction of genes in new genome sequences which cannot be assigned functions at all also remains high, typically around 30% (3). There is thus a great need for new approaches to supplement sequence-based prediction methods for assigning biological functions in genome annotations.

In this study, we used large-scale phenotyping to assign functions to genes of a nonmodel prokaryote, Francisella novicida. Large-scale phenotyping has largely been restricted to model organisms for which libraries of deletion-insertion mutants have long been available. For example, chemogenomic profiling of Saccharomyces cerevisiae using highly sensitive growth assays detected phenotypes for most genes (4), and studies of Escherichia coli defined numerous antibiotic resistance, other inhibitor resistance, and carbon source utilization genes (5–8). Large-scale phenotyping has recently been extended to two nonmodel species through the analysis of sequence-defined libraries of transposon mutants (9–11). One study examined Shewanella oneidensis and identified functions for 40 underannotated genes (11). A second study examined Pseudomonas aeruginosa but did not provide specific genotype-phenotype associations (10)

F. novicida is a low-virulence surrogate of F. tularensis, one of the most infectious pathogens known (12–14). F. novicida is ideal for genomic studies of virulence and other processes because it has a small genome (1.9 Mbp) and may be readily manipulated (15, 16). In addition, a manual genome annotation is available (http://go.francisella.org/cgi-bin/frangb/elementlist.cgi?gac=Francisella_tularensis_novicida_U112) (17), and a near-saturation, sequence-defined transposon mutant library has been created (18). In this study, we sought to evaluate genome annotation predictions by examining growth of the members of the library under a variety of nutritional and stress conditions. The results provide direct tests of annotation assignments and specify numerous unexpected genotype-phenotype associations.

RESULTS

F. novicida phenotyping was carried out using an arrayed, sequence-defined transposon mutant library. Growth of the members of the library on a variety of agar media was quantified using image processing. The growth conditions examined were chosen to help define the genetic basis of nutrition and resistance traits potentially important in both the process of Francisella infection and in its response to antimicrobial therapy. For broadly distributed traits that have been characterized in other bacteria (such as intrinsic antibiotic resistance), the tests also aimed to identify conserved elements.

Three-allele transposon mutant library.

We sought to analyze multiple independent mutants for each gene to provide confirmation of genotype-phenotype assignments. This redundancy should minimize erroneous assignments due to allele-specific effects, unlinked mutations, and cross-contamination. We therefore assembled a mutant library made up of an average of three different insertion mutants per predicted gene by supplementing a previously assembled two-allele library with mutants from a larger primary library (18). The new three-allele library contains a total of 4,571 mutants, with 1,456 of 1,767 genes represented. The library includes strains with mutations in virtually all protein-coding genes nonessential for growth on nutrient medium (Trypticase soy agar plus cysteine). The genomic locations of nearly all (97.5%) of the transposon insertions in the library were confirmed by at least two independent sequencings. The number of different insertions per gene are 0 (311 genes), 1 (133 genes), 2 (177 genes), 3 (748 genes), 4 (289 genes), and ≥5 (109 genes). There are 111 predicted insertions in intergenic regions. The 311 unrepresented genes are presumably essential.

Mutant phenotyping.

We examined 38 phenotypes corresponding to nutritional and stress resistance traits, including antibiotic resistance (Materials and Methods). The growth yields of mutants of the three-allele library were assayed after spotting on agar medium in a 384-well format and incubation for 24 to 48 h. Plates were imaged under dark-field illumination using high-resolution digital photography, and the images were processed to quantify growth of each mutant spot. Duplicate tests of each condition were carried out, and results for individual mutant alleles were averaged. A growth difference from the norm was considered significant if the probability of its arising by chance was less than 0.01.

A total of 4,445 mutants yielded reproducible data (see Data Set S1 in the supplemental material), with 37% (545/1,456) of the genes analyzed exhibiting mutant phenotypes (see Data Set S2). Most of the genotype-phenotype associations (82%) were confirmed for multiple mutations in a given gene. The remainder (18%) corresponded to genes for which only one allele was represented in the library. (Cases in which only one of multiple alleles led to a phenotype were not included in Data Set S2.) Approximately 23% (123/545) of the genes with mutant phenotypes were annotated as hypothetical genes and other genes of unknown function, 19% (103/545) were assigned general functions only (e.g., ABC transporter, ATP-binding protein) and 58% (319/545) were assigned specific functions (e.g., recombinase A protein).

Carbon source utilization.

We examined growth of members of the three-allele library on thirteen carbon sources, including sugars and short-chain compounds. The choice of carbon sources was guided by the results of a phenotypic microarray screen of the wild-type strain (19).

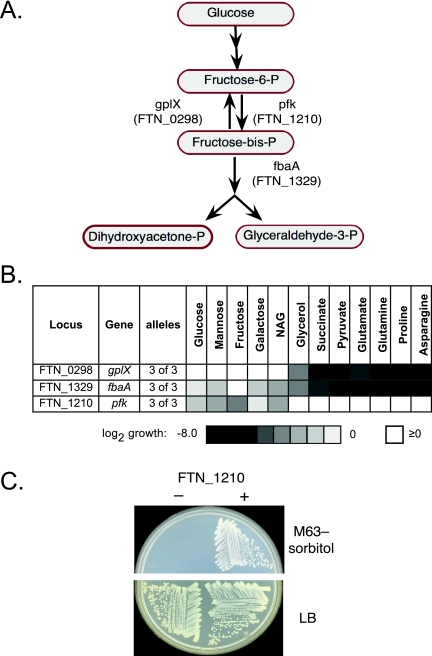

The genome annotation predicted complete glycolytic and gluconeogenic pathways, with the exception of phosphofructokinase. Mutations inactivating two steps of the pathways (fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase [gplX] and fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase [fbaA]) were represented in the library and led to pleiotropic phenotypes compatible with their roles (Fig. 1A and B). Mutations in a third gene (FTN_1210) prevented growth on sugars but not on short-chain carbon sources, suggesting a block in glycolysis. Since the FTN_1210 product shows sequence homology to sugar kinases (and was originally annotated as a ribokinase), the phenotype suggests that the gene encodes the missing phosphofructokinase.

FIG 1 .

Identification of the F. novicida phosphofructokinase gene. (A) Glycolysis pathway steps. F. novicida gene assignments are derived from the sequence annotation, and results are presented here. (B) Growth of mutants on different carbon sources. The gluconeogenesis mutant (gplX) is selectively defective for growth on short-chain carbon sources, whereas the aldolase mutant (fbaA), defective in both glycolysis and gluconeogenesis, is defective for growth on both sugars and short-chain carbon sources. Mutations in FTN_1210 lead to defects in growth on sugars, suggesting a glycolysis defect. NAG, N-acetylglucosamine. (C) Complementation of an E. coli phosphofructokinase mutant with FTN_1210. The pronounced growth defect of an E. coli pfk mutant (JW3887) on sorbitol as the carbon source (40) is complemented by expression of FTN_1210, supporting its assignment as the pfk gene. FTN_1210 also complemented an E. coli pfk mutant growth defect on glucose (not shown).

To test this assignment, we examined whether cloned FTN_1210 could complement an E. coli phosphofructokinase mutant. The Francisella gene did indeed correct the mutant E. coli carbon source utilization defect (Fig. 1C), providing strong support for assignment of FTN_1210 as the phosphofructokinase gene (pfk).

The assays also identified catabolic pathways for ten compounds (Table 1), seven of which had been fully predicted in the sequence annotation. For the eighth (N-acetylglucosamine), the results suggest a possible pathway for which three of four steps were new (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), for the ninth (mannose), a required kinase was identified that also acts on fructose (see Fig. S2), and for the tenth (fructose), a transporter (FruP) and an isomerization function (ManA) were identified.

TABLE 1 .

Summary of nutritional phenotypesa

| Pathway | Pathway genes |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Unpredicted | Other unpredicted genes | ||

| Carbon source utilization | ||||

| Glucoseb | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Galactoseb | 4 | 0 | 1 | |

| N-Acetylglucosamineb | 1 | 3 | 1 | |

| Mannoseb | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Fructoseb | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Glycerolb | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Succinate | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Pyruvate | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Glutamateb | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Glutamineb | 1 | 0 | 6 | |

| Prolineb | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Asparagineb | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Biosynthesis | ||||

| Purinesb | 8 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pyrimidinesb | 7 | 0 | 0 | |

| Leucineb | 4 | 0 | 2 | |

| Isoleucine-valineb | 5 | 1 | 1 | |

| Threonineb | 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| Lysine | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| Aromatic amino acids | 12 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pantothenate | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

The numbers of genes associated with different nutritional defects are shown according to whether or not they were predicted by annotation. Specific genes are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material

Complete pathway identified.

For many of the carbon sources, there were mutant assignments that could not be readily fitted into the predicted pathways (Table 1; also, see Table S1 in the supplemental material). For example, mutations inactivating a predicted quinate/shikimate dehydrogenase (FTN_0511) led to a relatively specific defect in fructose utilization, and mutations inactivating a predicted glycogen-biosynthetic function (glgB) blocked growth on multiple sugars.

Amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis.

F. novicida is naturally auxotrophic for four amino acids (arginine, histidine, methionine, and cysteine) but can synthesize the remaining amino acids and nucleotides. Mutant library analysis identified most or all steps of the pathways for the synthesis of leucine, isoleucine/valine, threonine, lysine, phenylalanine/tyrosine/tryptophan, purines, pyrimidines, and pantothenate, suggesting several new assignments in the process (Table 1; also, see Table S1 in the supplemental material).

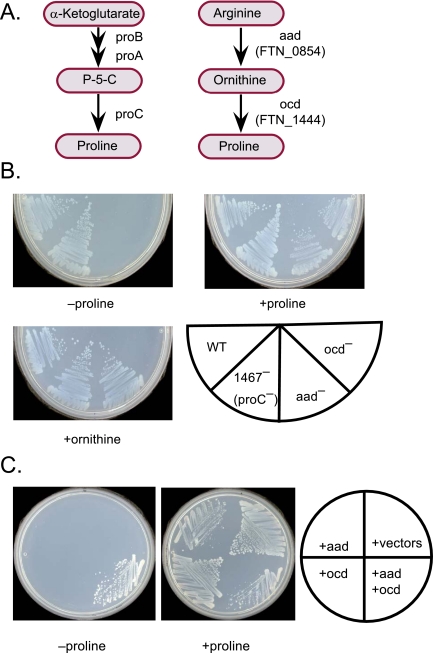

Proline presented an unusual case. Although F. novicida lacks the proline-biosynthetic pathway (ProABC) found in E. coli (Fig. 2A, left), the organism could grow in the absence of proline if a substitute source of α-ketoglutarate (such as its transamination product glutamate) was provided, presumably as a source of carbon for the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Four findings implied that F. novicida encodes a pathway for generating proline from arginine (Fig. 2A, right). First, a screen for mutants requiring proline identified two genes (FTN_0854 and FTN_1444) with predicted enzymatic functions (aminotransferase and ornithine cyclodeaminase) compatible with the pathway (Fig. 2B). Second, the proline requirement of FTN_0854 (aad) mutants could be satisfied by ornithine (Fig. 2B). Third, mutations inactivating a proC homolog (FTN_1467) did not lead to proline auxotrophy (Fig. 2B). Finally, the FTN_0854 (aad) and FTN_1444 genes (ocd) complemented the proline requirement of an E. coli proAB deletion mutant (Fig. 2C). Both genes were necessary. The F. novicida proline-biosynthetic pathway resembles the arginine catabolic pathway encoded by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid (20) but generates ornithine from arginine by means of an amidinotransferase rather than an arginase step.

FIG 2 .

Proline biosynthesis. (A) Proline-biosynthetic pathway. (Left) Pathway found in E. coli; (right) proposed pathway for F. novicida. P-5-C, 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate; aad, arginine amidinotransferase gene (amidino group [-CNHNH2] acceptor unknown); ocd, ornithine cyclodeaminase gene. (B) F. novicida proline auxotrophs. Mutations in aad and ocd genes prevented growth on medium lacking proline (FNDM supplemented with glutamate) (see Text S1 in the supplemental material). As predicted, aad mutants grew without proline in medium containing ornithine. Mutations in a proC homolog (FTN_1467) did not reduce growth on medium lacking proline. (C) Complementation of an E. coli proline auxotroph. Expression of aad and ocd in E. coli complemented a proAB deletion mutant (M8820) for growth in the absence of proline.

Mutants defective in early steps of the lysine-biosynthetic pathway (dapABDE) did not require diaminopimelate (DAP), even though DAP is the immediate precursor of lysine and is normally essential. Furthermore, genes encoding the DAP-lysine-biosynthetic pathway are absent from highly virulent Francisella genomes (21). The results raise the possibility that DAP is not required for peptidoglycan biosynthesis in Francisella.

Resistance to multiple antibiotics.

Mutations in several genes increased sensitivity to multiple antibiotics and other agents (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Mutants with related sensitivity patterns affected genes for the AcrAB efflux pump (FTN_1609-1610) (22), and a TolC homolog (FTN_1703) (23), suggesting that they may function together. Two additional potential efflux transporters were also identified (FTN_0570 and FTN_1180-1181), as was a potential rhodanese family sulfurtransferase (FTN_0120).

Resistance to quinolone antibiotics.

The quinolone antibiotics ciprofloxacin and nalidixic acid inhibit DNA gyrase, leading to double-strand DNA breaks. Accordingly, many of the mutations increasing sensitivity to these antibiotics affect DNA recombination and repair functions, including recABCD and ruvABC (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). Homologs of many of the F. novicida resistance functions also contribute to quinolone resistance in E. coli (5, 6). Novel functions include a replication helicase (rep) and exonuclease I (sbcB).

Resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as gentamicin, target the 30S ribosome subunit to enhance misreading, resulting in aberrant proteins that compromise membrane integrity (24). Mutations in four genes associated with proteolysis (hslVU, yccA, and sohB) enhance aminoglycoside sensitivity (Fig. 3), consistent with previous results suggesting that proteolysis of mistranslation products may be protective (25). The E. coli homolog of one of the functions (YccA) facilitates the destruction of secretion complexes “jammed” by proteins unable to be secreted (26). Mistranslation products unable to be secreted could be eliminated in an analogous manner. Mutations reducing export capacity (such as in secG and yidD) could increase the sensitivity of cells to such jamming by reducing the number of functional secretion complexes. Many aminoglycoside sensitive mutants were pleiotropic, with increased sensitivities to conditions such as elevated temperature and pH, presumably as a consequence of elevated sensitivity to mistranslation products even in the absence of antibiotic.

FIG 3 .

Aminoglycoside hypersensitive mutants. Mutations leading to increased streptomycin and gentamicin sensitivity are shown. Shadings reflect average growth of the two alleles with the strongest defects for each gene, and nutritional phenotypes are not shown. Asterisks indicate cases in which polar effects on expression of downstream genes could contribute to phenotypes. Several genes whose inactivation led to pleiotropic phenotypes are not included (plsC, glnA, FTN_0802, and FTN_0917). The number of mutant alleles for each gene leading to increased sensitivity is provided. Functions associated with intrinsic aminoglycoside resistance in E. coli or P. aeruginosa are indicated (5, 6, 25, 27).

About half of the genes contributing to aminoglycoside resistance in F. novicida have been associated with intrinsic aminoglycoside resistance in E. coli or P. aeruginosa (5, 6, 25, 27). The result suggests that the mechanisms responsible for intrinsic aminoglycoside resistance are at least partially conserved in the three species.

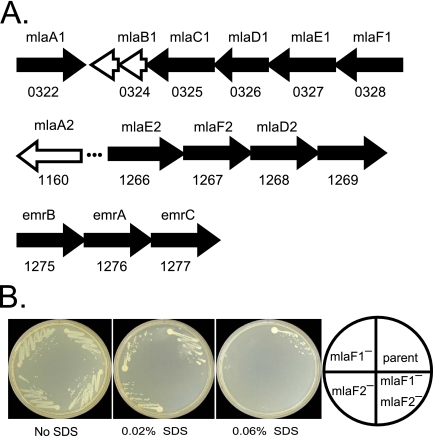

Resistance to SDS.

Mutations in three clusters of predicted transport genes enhanced sensitivity to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (Fig. 4A). Two of the clusters corresponded to an E. coli ABC transport system (mlaABCDEF) that helps maintain outer membrane phospholipid asymmetry (28), and a third (emrABC) encodes a putative efflux pump similar to one in E. coli that confers resistance to hydrophobic compounds (29).

FIG 4 .

SDS resistance genes. (A) Three clusters of transport genes contributing to SDS resistance are shown. Genes in which mutations led to SDS sensitivity are shaded black. Two of the clusters encode homologs of the E. coli mlaABCDEF genes involved in outer membrane lipid quality control. FTN_1269 may substitute for the missing mlaC2 function. (B) Mla mutant sensitivities. The growth defects of single and double mla mutants on TSAC containing increasing levels of SDS are shown. Note that the mlaF1-mlaF2 double mutant is more SDS sensitive than the parent single mutants. Similar results were seen for mlaD1 and mlaD2 single and double mutants (not shown).

Two F. novicida homologs are represented for three of the mla genes (mlaDEF), indicating that there are two independent pathways. If the two Mla pathways function independently, a double mutant in which both are inactive should be more SDS sensitive than either parental single mutant. Indeed, the growth of the double mutants was completely inhibited at a concentration of SDS on which the parent single mutants grew well (Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

The primary goal of this study was to help assign biological functions to a significant number of F. novicida genes through large-scale phenotyping. Assigning biological functions experimentally complements the use of sequence similarity to predict function and should strengthen the foundation for the genetic dissection of complex traits. This “phenotypic annotation” should contribute to an understanding of Francisella virulence, which requires metabolic and stress resistance adaptations controlled by hundreds of genes (30–35).

Our analysis employed a library of arrayed, sequence-defined transposon mutants with insertions in nearly all nonessential genes. On average, three mutants for each gene were assayed to provide confirmation of genotype-phenotype assignments and to minimize missed assignments. It was crucial to incorporate this redundancy into the analysis, since a significant number of individual mutants exhibited unrepresentative phenotypes. A total of 39 nutritional and stress sensitivity phenotypes were examined using image analysis to quantify growth of individual strains.

There are several limitations in using the approach presented here to define gene function. First, transposon insertion mutations can cause polar effects on gene expression. In this study, cases in which a phenotype may be due to polarity can generally be recognized as adjacent genes in the same orientation with overlapping mutant phenotypes. Second, the relationship between a mutation and a phenotype can be indirect. Third, the absence of a phenotype for a mutation may be due to redundant functions, which mask the effects of the genetic defect. One advantage of F. novicida as a test organism is that its genome is small, which presumably limits the extent of such redundancy.

Mutant phenotypes were identified for 37% of the nonessential genes of the organism. The genes ranged from those with “complete” annotation predictions (i.e., including both molecular and biological activities) to those lacking predicted functions altogether. The genotype-phenotype associations we identified thus both provide tests of annotation predictions and help specify the functions of underannotated genes.

The screen identified the genes responsible for ten carbon source utilization pathways, nine amino acid and nucleotide biosynthesis pathways, seven intrinsic antibiotic resistance and six additional stress resistance networks. For most of the phenotypes, there were unexpected gene associations, and for some, the majority of assignments were new. We assume that the large number of new assignments reflects both physiological novelty in F. novicida and incomplete characterization of some of the traits in model species.

Although nearly every phenotype we examined presented novel elements, there were several particularly noteworthy findings. (i) The identification of a putative phosphofructokinase in F. novicida completes the glycolytic pathway. Homologs are found in highly virulent Francisella strains (17). (ii) Proline biosynthesis in F. novicida is carried out using a two-step pathway that employs the essential amino acid arginine as precursor. The pathway appears to be nonfunctional in highly virulent Francisella strains in which both genes carry inactivating mutations (17). (iii) Diaminopimelic acid may not be required for peptidoglycan synthesis. (iv) Three potential drug efflux functions were identified, two of which were new. (v) A subset of quinolone and aminoglycoside intrinsic resistance functions of F. novicida is shared with E. coli and/or P. aeruginosa (5, 25). (vi) There appear to be two Mla transport systems that eliminate phospholipids from the outer leaflet of the outer membrane and confer detergent resistance. The redundancy may compensate for the apparent absence of an outer membrane phospholipase A1 (28).

Although our analysis was restricted to basic growth phenotypes, the data set of results includes associations that may help in understanding more complex traits, such as virulence. For example, Weiss et al. identified 164 F. novicida genes required for survival or growth in mice (32). About half of these genes were associated with growth phenotypes in our study, including 33 genes with undefined or incompletely defined functional annotations (data not shown). Among the functionally undefined genes were ones whose inactivation led to enhanced sensitivity to temperature (FTN_0599), pH (FTN_1582), and detergent (FTN_1548), as well as carbon source utilization defects (FTN_1016 and FTN_1656). Several other screens for virulence genes provide additional examples (30, 31, 33) (data not shown). The phenotypes represent potential starting points for further analysis of the roles of these genes in virulence.

This study shows that large-scale phenotypic analysis can provide a direct evaluation of genome annotation predictions and serve as a source of discovery even for well-characterized processes. The recent development of deep-sequencing methods for tracking transposon mutants in large populations should complement the approach presented here and make it possible to extend genome-scale phenotyping to prokaryotes for which defined mutant libraries are not yet available (27, 36–39).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth and imaging of F. novicida mutants.

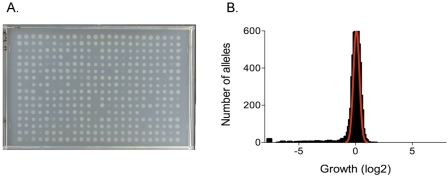

F. novicida mutant library plates were thawed and aliquots deposited onto agar test plates using a QPIX robot (Genetix) fitted with a floating head replicator (V &P Scientific AFIXP96FP6). The replicator deposits about 1 microliter per strain, corresponding to about 5 × 105 cells. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C (with the exception of the 46°C and SDS plates, which were incubated for 24 h) to allow growth of bacteria. Following incubation, a digital image of each plate was created using a Nikon D70 camera (28-mm lens) mounted on a dark field photographic assembly built for this project. In this setup, test plates were illuminated indirectly from below. Bacterial spots scatter more light than the surrounding agar, making them brighter than the agar background in the resulting images. The intensity of spots measured from the images as described below was approximately linear with cell number, as measured by viable counts (not shown). An image of a representative plate of mutant spots illustrates the range of different growth yields observed (Fig. 5A).

FIG 5 .

Analysis of growth phenotypes. (A) Growth of mutant cells. The growth of mutant spots in 384-well array format on one of the test media (FNDM-glucose) after 24 h of incubation is shown. Mutants exhibiting reduced growth are evident. (B) Distribution of mutant growth yields. A histogram representing growth of the three-allele mutant library on FNDM-glucose is shown. A tail to the left of mutants with reduced growth is evident. A normal distribution curve fitted to the peak centered at zero is shown.

Data analysis.

The growth of bacterial spots was quantified from high-resolution images (see the supplemental material). Analysis of data was carried out in several steps. First, growth values for each mutant from independent assays (two or more per condition) were averaged. Second, mutants growing poorly on unsupplemented TSAC medium (values of ≤0.4) were eliminated (69 strains total). Third, the growth values of the remaining mutants (4,445 strains) were normalized to the growth on unsupplemented TSAC and log2 transformed. Complete results are presented in Data Set S1.

For each condition, growth values were centered near a log2 of 0 with a conspicuous tail corresponding to mutants with decreased growth (Fig. 5B). To identify mutants with significantly decreased or increased growth, we assumed that the growth values in the peaks centered at a log2 of 0 were approximately normally distributed (Fig. 5B). Strains whose growth differed significantly from the norm (P value of ≤0.01 or ≥0.99) were considered candidates for the corresponding mutant phenotypes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Cases in which at least two different mutant alleles of a gene led to a phenotype defined confirmed genotype-phenotype associations (see Data Set S2). Cases in which only one mutation in a gene led to a phenotype were disregarded unless it was the sole mutant allele examined for the gene; these cases defined unconfirmed genotype-phenotype associations and were included in Data Set S2.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental Materials and Methods. Download Text S1, DOCX file, 0.1 MB.

Mutant growth data. Growth data for all mutants analyzed are provided. Values are averages of two or more independent measurements. Download Data Set S1, XLSX file, 1.9 MB.

Confirmed mutant phenotypes. Growth values in which two insertion alleles shared at least one significant phenotype are shown. Cases in which genes are represented in the library by one mutant (for which confirmation was thus not possible) are also included, while those for which only one of multiple alleles exhibited a phenotype are not included. Download Data Set S2, XLSX file, 0.3 MB.

N-Acetylglucosamine utilization pathway mutants. Mutations in the predicted NagA deacetylase gene (FTN_1149) prevented N-acetylglucosamine utilization, as expected. Three additional gene functions were needed for growth on N-acetylglucosamine: a predicted sugar porter, FTN_1079 (here named nagP), glucokinase (glk), and a putative transaminase, FTN_1080 (nagB). The FTN_1080 (nagB) product was annotated as a phosphosugar-binding protein and appears to encode a glutamine fructose-6-phosphate transaminase related to GlmS (FTN_0485). Mutations in a predicted efflux gene (FTN_1685) also blocked growth on N-acetylglucosamine. NAG, N-acetylglucosamine; nag-6P, N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate. Download Figure S1, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Fructose- and mannose-negative mutants. Mutations in the gene predicted to encode mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (manA, FTN_0408) prevented growth on mannose, as expected (see Data Set S2). Two additional genes required for growth on the sugars correspond to a predicted sugar kinase (FTN_0646), which appears to act on both fructose and mannose, and a predicted transporter (FTN_0688), which appears to import fructose. Mutations in FTN_0511 and FTN_0512 (glgX) also led to fructose-negative phenotypes. Download Figure S2, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Mutants sensitive to multiple antibiotics. Shadings correspond to the averages of the two strongest alleles for each gene. Nutritional phenotypes are not shown. Asterisks indicate cases in which polar effects on expression of downstream genes could contribute to phenotypes. The number of mutant alleles for each gene leading to increased sensitivity is provided. Download Figure S3, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Quinolone antibiotic-hypersensitive mutants. Mutations leading to increased ciprofloxacin and/or nalidixic acid sensitivity are shown. Shadings correspond to the averages of the two strongest alleles for each gene. Nutritional phenotypes are not shown. Asterisks indicate cases in which polar effects on expression of downstream genes could contribute to phenotypes. Several genes with strong mutant phenotypes that could be explained by polarity were not included in the table (FTN_0120, FTN_121, FTN_0188, FTN_400, and FTN_401). The number of mutant alleles for each gene leading to increased sensitivity is provided. Functions associated with quinolone intrinsic resistance in E. coli are indicated. Download Figure S4, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Summary of nutritional phenotypes. Genes associated with carbon source utilization or biosynthetic defects are listed according to whether or not they were predicted by annotation.

Growth yield distributions. Statistical parameters are shown for the growth yield distributions under different conditions of the complete set of mutants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Maynard Olson, Pradeep Singh, Pete Greenberg and Lazlo Csonka for helpful discussions.

The work was supported by NIH grant U54AI057141.

Footnotes

Citation Enstrom M, et al. 2012. Genotype-phenotype associations in a nonmodel prokaryote. mBio 3(2):e00001-12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00001-12.

REFERENCES

- 1. Reeves GA, Talavera D, Thornton JM. 2009. Genome and proteome annotation: organization, interpretation and integration. J. R. Soc. Interface 6:129–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galperin MY, Koonin EV. 2010. From complete genome sequence to “complete” understanding? Trends Biotechnol. 28:398–406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kasif S, Steffen M. 2010. Biochemical networks: the evolution of gene annotation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6:4–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hillenmeyer ME, et al. 2008. The chemical genomic portrait of yeast: uncovering a phenotype for all genes. Science 320:362–365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tamae C, et al. 2008. Determination of antibiotic hypersensitivity among 4,000 single-gene-knockout mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 190:5981–5988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nichols RJ, et al. 2011. Phenotypic landscape of a bacterial cell. Cell 144:143–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Girgis HS, Hottes AK, Tavazoie S. 2009. Genetic architecture of intrinsic antibiotic susceptibility. PLoS One 4:e5629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ito M, Baba T, Mori H, Mori H. 2005. Functional analysis of 1440 Escherichia coli genes using the combination of knockout library and phenotype microarrays. Metab. Eng. 7:318–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Salama NR, Manoil C. 2006. Seeking completeness in bacterial mutant hunts. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:307–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pommerenke C, et al. 2010. Global genotype-phenotype correlations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deutschbauer A, et al. 2011. Evidence-based annotation of gene function in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 using genome-wide fitness profiling across 121 conditions. PLoS Genet. 7:e1002385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barker JR, Klose KE. 2007. Molecular and genetic basis of pathogenesis in Francisella tularensis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1105:138–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nano FE, Schmerk C. 2007. The Francisella pathogenicity island. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1105:122–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dai S, Mohapatra NP, Schlesinger LS, Gunn JS. 2010. Regulation of Francisella tularensis virulence. Front Microbiol. 1:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ludu JS, et al. 2008. Genetic elements for selection, deletion mutagenesis and complementation in Francisella spp. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 278:86–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zogaj X, Klose KE. 2010. Genetic manipulation of Francisella tularensis. Front. Microbiol. 1:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rohmer L, et al. 2007. Comparison of Francisella tularensis genomes reveals evolutionary events associated with the emergence of human pathogenic strains. Genome Biol. 8:R102–R102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gallagher LA, et al. 2007. A comprehensive transposon mutant library of Francisella novicida, a bioweapon surrogate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:1009–1014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bochner BR. 2003. New technologies to assess genotype-phenotype relationships. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4:309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sans N, Schröder G, Schröder J. 1987. The Noc region of Ti plasmid C58 codes for arginase and ornithine cyclodeaminase. Eur. J. Biochem. 167:81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brittnacher MJ, et al. 2011. PGAT: a multistrain analysis resource for microbial genomes. Bioinformatics 27:2429–2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bina XR, Lavine CL, Miller MA, Bina JE. 2008. The AcrAB RND efflux system from the live vaccine strain of Francisella tularensis is a multiple drug efflux system that is required for virulence in mice. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 279:226–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gil H, et al. 2006. Deletion of TolC orthologs in Francisella tularensis identifies roles in multidrug resistance and virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:12897–12902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davis BD. 1987. Mechanism of bactericidal action of aminoglycosides. Microbiol. Rev. 51:341–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee S, et al. 2009. Targeting a bacterial stress response to enhance antibiotic action. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:14570–14575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. van Stelten J, Silva F, Belin D, Silhavy TJ. 2009. Effects of antibiotics and a proto-oncogene homolog on destruction of protein translocator SecY. Science 325:753–756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gallagher LA, Shendure J, Manoil C. 2011. Genome-scale identification of resistance functions in Pseudomonas aeruginosa using Tn-seq. mBio 2:e00315-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malinverni JC, Silhavy TJ. 2009. An ABC transport system that maintains lipid asymmetry in the gram-negative outer membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:8009–8014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lomovskaya O, Lewis K. 1992. Emr, an Escherichia coli locus for multidrug resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:8938–8942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kraemer PS, et al. 2009. Genome-wide screen in Francisella novicida for genes required for pulmonary and systemic infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 77:232–244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lai XH, et al. 2010. Mutations of Francisella novicida that alter the mechanism of its phagocytosis by murine macrophages. PLoS One 5:e11857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Weiss DS, et al. 2007. In vivo negative selection screen identifies genes required for Francisella virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:6037–6042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Asare R, Abu Kwaik Y. 2010. Molecular complexity orchestrates modulation of phagosome biogenesis and escape to the cytosol of macrophages by Francisella tularensis. Environ. Microbiol. 12:2559–2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Su J, et al. 2007. Genome-wide identification of Francisella tularensis virulence determinants. Infect. Immun. 75:3089–3101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Charity JC, et al. 2007. Twin RNA polymerase-associated proteins control virulence gene expression in Francisella tularensis. PLoS Pathog. 3:e84–e84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Opijnen T, Bodi KL, Camilli A. 2009. Tn-seq: high-throughput parallel sequencing for fitness and genetic interaction studies in microorganisms. Nat. Methods 6:767–772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Langridge GC, et al. 2009. Simultaneous assay of every Salmonella typhi gene using one million transposon mutants. Genome Res. 19:2308–2316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gawronski JD, Wong SM, Giannoukos G, Ward DV, Akerley BJ. 2009. Tracking insertion mutants within libraries by deep sequencing and a genome-wide screen for Haemophilus genes required in the lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:16422–16427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Goodman AL, Wu M, Gordon JI. 2011. Identifying microbial fitness determinants by insertion sequencing using genome-wide transposon mutant libraries. Nat. Protoc. 6:1969–1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morrissey AT, Fraenkel DG. 1972. Suppressor of phosphofructokinase mutations of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 112:183–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Materials and Methods. Download Text S1, DOCX file, 0.1 MB.

Mutant growth data. Growth data for all mutants analyzed are provided. Values are averages of two or more independent measurements. Download Data Set S1, XLSX file, 1.9 MB.

Confirmed mutant phenotypes. Growth values in which two insertion alleles shared at least one significant phenotype are shown. Cases in which genes are represented in the library by one mutant (for which confirmation was thus not possible) are also included, while those for which only one of multiple alleles exhibited a phenotype are not included. Download Data Set S2, XLSX file, 0.3 MB.

N-Acetylglucosamine utilization pathway mutants. Mutations in the predicted NagA deacetylase gene (FTN_1149) prevented N-acetylglucosamine utilization, as expected. Three additional gene functions were needed for growth on N-acetylglucosamine: a predicted sugar porter, FTN_1079 (here named nagP), glucokinase (glk), and a putative transaminase, FTN_1080 (nagB). The FTN_1080 (nagB) product was annotated as a phosphosugar-binding protein and appears to encode a glutamine fructose-6-phosphate transaminase related to GlmS (FTN_0485). Mutations in a predicted efflux gene (FTN_1685) also blocked growth on N-acetylglucosamine. NAG, N-acetylglucosamine; nag-6P, N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate. Download Figure S1, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Fructose- and mannose-negative mutants. Mutations in the gene predicted to encode mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (manA, FTN_0408) prevented growth on mannose, as expected (see Data Set S2). Two additional genes required for growth on the sugars correspond to a predicted sugar kinase (FTN_0646), which appears to act on both fructose and mannose, and a predicted transporter (FTN_0688), which appears to import fructose. Mutations in FTN_0511 and FTN_0512 (glgX) also led to fructose-negative phenotypes. Download Figure S2, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Mutants sensitive to multiple antibiotics. Shadings correspond to the averages of the two strongest alleles for each gene. Nutritional phenotypes are not shown. Asterisks indicate cases in which polar effects on expression of downstream genes could contribute to phenotypes. The number of mutant alleles for each gene leading to increased sensitivity is provided. Download Figure S3, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Quinolone antibiotic-hypersensitive mutants. Mutations leading to increased ciprofloxacin and/or nalidixic acid sensitivity are shown. Shadings correspond to the averages of the two strongest alleles for each gene. Nutritional phenotypes are not shown. Asterisks indicate cases in which polar effects on expression of downstream genes could contribute to phenotypes. Several genes with strong mutant phenotypes that could be explained by polarity were not included in the table (FTN_0120, FTN_121, FTN_0188, FTN_400, and FTN_401). The number of mutant alleles for each gene leading to increased sensitivity is provided. Functions associated with quinolone intrinsic resistance in E. coli are indicated. Download Figure S4, PDF file, 0.1 MB.

Summary of nutritional phenotypes. Genes associated with carbon source utilization or biosynthetic defects are listed according to whether or not they were predicted by annotation.

Growth yield distributions. Statistical parameters are shown for the growth yield distributions under different conditions of the complete set of mutants.