Abstract

Background

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires pediatric residency programs to teach professionalism but does not provide concrete guidance for fulfilling these requirements. Individual programs, therefore, adopt their own methods for teaching and evaluating professionalism, and published research demonstrating how to satisfy the ACGME professionalism requirement is lacking.

Methods

We surveyed pediatric residency program directors in 2008 to explore the establishment of expectations for professional conduct, the educational experiences used to foster learning in professionalism, and the evaluation of professionalism.

Results

Surveys were completed by 96 of 189 program directors (51%). A majority reported that new interns attend a session during which expectations for professionalism are conveyed, either verbally (93%) or in writing (65%). However, most program directors reported that “None or Few” of their residents engaged in multiple educational experiences that could foster learning in professionalism. Despite the identification of professionalism as a core competency, a minority (28%) of programs had a written curriculum in ethics or professionalism. When evaluating professionalism, the most frequently used assessment strategies were rated as “very useful” by only a modest proportion (26%–54%) of respondents.

Conclusions

Few programs have written curricula in professionalism, and opportunities for experiential learning in professionalism may be limited. In addition, program directors express only moderate satisfaction with current strategies for evaluating professionalism that were available through 2008.

Editor's note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument (88KB, doc) used in this study.

Background

Teaching and assessment of professionalism are required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), and the medical literature both describes curricula for professionalism and suggests pedagogical approaches.1–5 At the same time, professionalism remains a significant educational challenge,6 and no interventions have been empirically proven to foster learning in professionalism.

The conceptual model by Stern and Papadakis7 for teaching professionalism includes setting expectations, providing experiences, and evaluating outcomes. Although their recommendations are focused on undergraduate medical education, they can be adapted to residency training. Guided by this model, we surveyed pediatric residency program directors to explore their strategies for satisfying ACGME requirements regarding professionalism.

Methods

Study Population

We identified participants from an ACGME list of pediatric residency program directors.8 A total of 189 participants met inclusion criteria.

Survey Instrument

Because no standard list of items about professionalism training exists, the survey included items derived from the medical literature and questions developed by 2 of the investigators (J.C.K. and T.C.S.), who are program directors or associate directors. We pilot-tested the instrument to ensure it captured the intended domains and revised it as needed to enhance clarity and ease of responding. The final 28-question survey instrument (provided as online supplemental material) asked how program directors set expectations for professional conduct; whether the program has a written curriculum in professionalism or ethics; what the educational experiences are that are used to teach professionalism; and whether residents had the opportunity to participate in experiences that could foster learning. Participants also rated their program's success in teaching professionalism, and the survey concluded with questions on the assessment of professionalism.

Survey Process

In the fall of 2008, we sent the online survey to program directors (Illume; DatStat, Inc., Seattle, WA). After 2 e-mail reminders, nonrespondents were sent a paper copy of the survey via Federal Express. Respondents were entered into a raffle for a $200 gift certificate.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which waived the requirement for documentation of consent. Analyses were descriptive and were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (Cary, North Carolina) statistical software.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

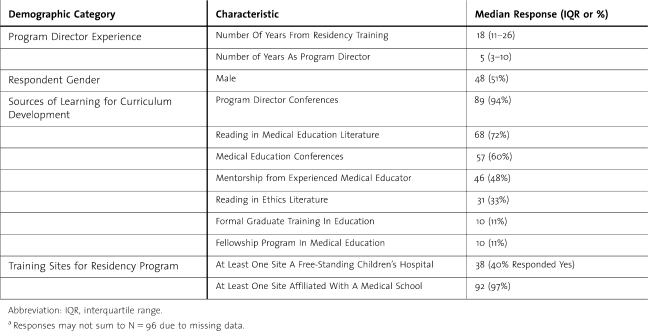

The response rate was 51% (96/189). Respondents reported a median of 18 years since completion of their own residency training and a median of 5 years of service as program directors (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Program Directors and Sources of Learning for Curriculum Development (N = 96)a Demographic Category

Setting Expectations for Professionalism

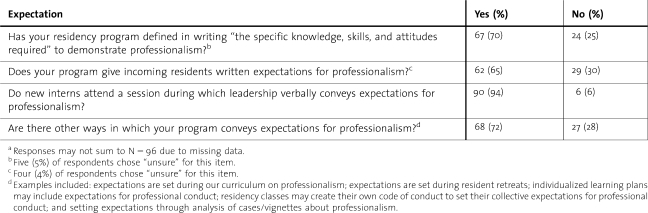

Seventy percent (67/96) of respondents reported that their program satisfied the ACGME requirement for teaching and assessment of professionalism. Most reported that new interns receive expectations for professionalism in writing (65% [62/96]) and verbally (93% [90/96]) (table 2).

TABLE 2.

Setting Expectations for Professionalism (N = 96)a

Experiences to Foster Learning in Ethics and Professionalism

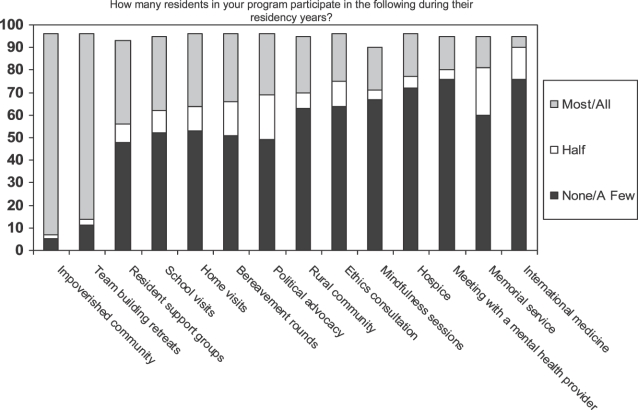

Twenty-eight percent (27/96) of respondents reported that their program had a written curriculum in ethics and/or professionalism, 46% (44/96) of respondents reported that their program had an unwritten curriculum, and 26% (25/96) of respondents responded that their program had no curriculum in this area. figure 1 shows the proportion of residents that participated in experiences that might foster learning in professionalism.

FIGURE 1.

Experiences to Foster Ethics and Professionalism (N = 96)

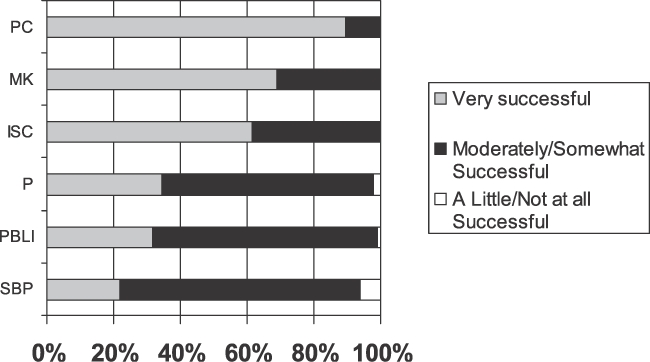

When assessing their own program's success in fulfilling each of the 6 ACGME core competencies (figure 2), fewer than half of program directors gave ratings of “very successful” to professionalism. Similarly, a minority indicated that their programs were “very successful” in achieving Systems-based Practice and Practice-based Learning and Improvement competencies.

FIGURE 2.

Program Directors' Ratings of Their Own Program's Success at Fulfilling ACGME Competencies

Abbreviations: PC = Patient Care, MK = Medical Knowledge, ISC = Interpersonal Skills and Communication, P = Professionalism, PBLI = Practice-based Learning and Improvement, SBP = Systems-based Practice.

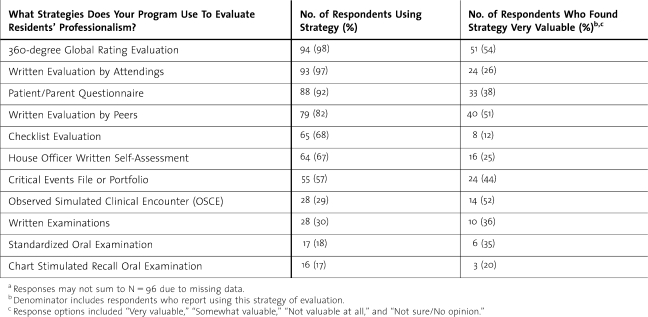

Evaluation of Professionalism

Program directors were asked what strategies they used for evaluating residents' professionalism (table 3). The strategies they used most frequently were those to which they assigned the highest value. Nevertheless, only 25%–53% (24–51/96) of respondents who reported using these evaluation tools rated them as “very valuable.”

TABLE 3.

Evaluation of Professionalism (N = 96)a

Discussion

Our survey found that a minority of program directors reported their program had a structured, written curriculum in ethics or professionalism. Most respondents reported that none or few of their residents participated in the majority of 14 experiences intended to foster learning in professionalism. Although respondents reported using multiple methods to evaluate professionalism, they rated the value of these strategies as modest at best.

Similar to a prior study,9 we found that many pediatric programs lack formal professionalism curricula. However, because our survey distinguished written from unwritten “curricula,” our data reveal that true written curricula are even less common than previously demonstrated. Only 28% of our respondents reported having written curricula, despite accreditation requirements for written documentation of educational experiences and plans to institute similar expectations for eligibility for graduate medical education (GME) payments.10,11

We applied a widely accepted conceptual model for professionalism education7 to broadly examine the setting of expectations for professional conduct, experiences provided to foster professionalism learning, and methods to evaluate professionalism. Adult learning theory indicates that lessons should be active and relevant to the learner's world,12–14 so experiential learning is an essential component of residency training. Program directors reported that few learners participate in experiential learning activities related to professionalism, such as visiting patients at home or in school, participating in ethics consultations or hospice care, or reflecting through memorial services or resident support groups, suggesting opportunities to expand and study experiential learning as an intervention to foster professionalism. Because effectively bolstering experiential learning to teach professionalism requires engagement and expertise of teaching faculty, our findings highlight the importance of faculty development to ensure the quality of training in this area.

Our study has several limitations. The instrument was limited by the lack of previously validated questions, methods, or measures of the elements of our conceptual model of professionalism education. To address this concern, we pilot-tested the instrument to ensure that the items measured the intended domains of professionalism training. Second, because no evidence-based list of experiences known to foster learning in professionalism is available, we compiled our own list for the survey. This list may facilitate curricular development and can guide future research about professionalism education. Third, the lack of availability of demographic data about nonresponding program directors hindered our ability to evaluate the generalizability of our findings. Fourth, in some cases, the program director may not be the individual who is the most knowledgeable about this topic within the program. In addition, programs may have updated their strategies for teaching and evaluating professionalism since the survey was conducted. Finally, the survey relies on self-reporting and is subject to bias.

Our data indicate that providing educational experiences to teach professionalism and adequately evaluating professionalism remain significant challenges in GME.

Conclusions

Our findings of a paucity of formal curricula and experiential learning to foster professionalism reinforces concerns that the teaching of professionalism is increasingly complex6 and that medical educators feel limited in their abilities to effectively teach this content.15 Our data show that many program directors do not consider themselves successful at fulfilling the professionalism competency.

Our study also sheds light on the evaluation of professionalism in the context of the ACGME requirement for evaluating the competencies and efforts to improve the quality of evaluations.16 Program leaders may benefit from additional training in implementing instruments to evaluate professionalism and interpreting data derived from them. The American Board of Pediatrics has developed an instrument for the assessment of professionalism,22 and the experience of educators in other specialties may be useful for pediatric program directors. For example, 360-degree global rating evaluations (multisource feedback) have demonstrated validity and reliability in various practice settings, indicating that they may have more potential value than our respondents perceive.17,18 The mini-clinical evaluation exercise (mini-CEX), a direct observation technique that has been recommended by medical educators in internal medicine,19,20 may prove valuable as well. Finally, the development of new instruments may yield additional strategies for evaluating professionalism.

Footnotes

Jennifer C. Kesselheim, MD, MBE, MEd, is faculty at the Department of Pediatric Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and the Department of Medicine, Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Theodore C. Sectish, MD, is faculty at the Department of Medicine, Children's Hospital, Boston, MA; Steven Joffe, MD, MPH, is faculty at the Department of Pediatric Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and the Department of Medicine, Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

References

- 1.Fallat ME, Glover J. Professionalism in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):e1123–e1133. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goold SD, Stern DT. Ethics and professionalism: what does a resident need to learn. Am J Bioeth. 2006;6(4):9–17. doi: 10.1080/15265160600755409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huddle TS. Viewpoint: teaching professionalism: is medical morality a competency. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):885–891. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saultz JW. Are we serious about teaching professionalism in medicine. Acad Med. 2007;82(6):574–577. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3180555c5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitcomb ME. Medical professionalism: can it be taught. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):883–884. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafferty FW, Castellani B. The increasing complexities of professionalism. Acad Med. 2010;85(2):288–301. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c85b43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stern DT, Papadakis M. The developing physician: becoming a professional. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(17):1794–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Listing of accredited training programs and directors. http://www.acgme.org/adspublic/. Accessed January 13, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang CW, Smith PJ, Ross LF. Ethics and professionalism in the pediatric curriculum: a survey of pediatric program directors. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1143–1151. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hackbarth G, Boccuti C. Transforming graduate medical education to improve health care value. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):693–695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1012691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iglehart J. Health reform, primary care, and graduate medical education. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):584–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1006115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman S. The educational Kanban: promoting effective self-directed adult learning in medical education. Acad Med. 2009;84(7):927–934. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a8177b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartzell JD. Adult learning theory in medical education. Am J Med. 2007;120(11):e11–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludmerer KM. Learner-centered medical education. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1163–1164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bryden P, Ginsburg S, Kurabi B, Ahmed N. Professing professionalism: are we our own worst enemy? Faculty members' experiences of teaching and evaluating professionalism in medical education at one school. Acad Med. 2010;85(6):1025–1034. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ce64ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swing SR CS, Holmboe ES, Williams RG. Advancing resident assessment in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):278–286. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00010.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi R, Ling FW, Jaeger J. Assessment of a 360-degree instrument to evaluate residents' competency in interpersonal and communication skills. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):458–463. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massagli TL, Carline JD. Reliability of a 360-degree evaluation to assess resident competence. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86(10):845–852. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318151ff5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Board of Internal Medicine. Mini clinical evaluation exercise. http://www.abim.org/pdf/paper-tools/mini-cex.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kogan JR, Holmboe ES, Hauer KE. Tools for direct observation and assessment of clinical skills of medical trainees: a systematic review. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1316–1326. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Board of Medical Examiners. AoPBASI, 2010. http://www.nbme.org/apb. requested January 13, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Board of Pediatrics. Teaching and assessing professionalism: a program directors guide. https://www.abp.org/abpwebsite/publicat/professionalism.pdf. Accessed January 13, 2012. [Google Scholar]