Abstract

Background

The Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) service for unhealthy alcohol use has been shown to be one of the most cost-effective medical preventive services and has been associated with long-term reductions in alcohol use and health care utilization. Recent studies also indicate that SBIRT reduces illicit drug use. In 2008 and 2009, the Substance Abuse Mental Health Service Administration funded 17 grantees to develop and implement medical residency training programs that teach residents how to provide SBIRT services for individuals with alcohol and drug misuse conditions. This paper presents the curricular activities associated with this initiative.

Methods

We used an online survey delivery application (Qualtrics) to e-mail a survey instrument developed by the project directors of 4 SBIRT residency programs to each residency grantee's director. The survey included both quantitative and qualitative data.

Results

All 17 (100%) grantees responded. Respondents encompassed residency programs in emergency medicine, family medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics-gynecology, psychiatry, surgery, and preventive medicine. Thirteen of 17 (76%) grantee programs used both online and in-person approaches to deliver the curriculum. All 17 grantees incorporated motivational interviewing and validated screening instruments in the curriculum. As of June 2011, 2867 residents had been trained, and project directors reported all residents were incorporating SBIRT into their practices. Consistently mentioned challenges in implementing an SBIRT curriculum included finding time in residents' schedules for the modules and the need for trained faculty to verify resident competence.

Conclusions

The SBIRT initiative has resulted in rapid development of educational programs and a cohort of residents who utilize SBIRT in practice. Skills verification, program dissemination, and sustainability after grant funding ends remain ongoing challenges.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains the survey instrument (818.2KB, pdf) used in this study.

What was known

Brief interventions for unhealthy alcohol use are highly effective, but many physicians self-report low efficacy and, consequently, low use in practice.

What is new

The Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) program has trained nearly 3000 residents to provide interventions that include motivational interviewing and use of validated screening instruments.

Limitations

Implementation challenges include finding time to teach the curriculum, training faculty, and sustaining the program after grant funding.

Bottom line

SBIRT has resulted in the rapid dissemination of an intervention addressing unhealthy alcohol use, and a cohort of residents who use it in practice.

Background

Screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is one of the most cost-effective medical preventive services1,2 and has been associated with long-term reductions in alcohol and illicit drug use3,4 and associated health care utilization.5 Rates of alcohol and drug misuse range from 8% to 40% among patients6 and are associated with poorer medication adherence, increased traumatic injury, and poorer prognosis for many chronic conditions,7 as well as higher health care costs.8 There is considerable variance among states and payers in recognizing and reimbursing SBIRT services, and current deployment of SBIRT in general medical settings is low.9–14 Low screening and intervention rates correlate consistently with lack of training and low clinician self-efficacy in this area.9–14

In 2008 the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) granted 17 five-year cooperative agreements for SBIRT medical residency programs with a total award of $19 million. The aim was to develop and implement training programs to teach residents how to provide evidence-based screening, brief intervention, brief treatment, and referral to specialty treatment for patients who either have or are at increased risk for a substance use disorder. The initiative was based on the premise that piloting curricula in various residencies around the country would ultimately result in a set of common training tools and implementation strategies that facilitate the adoption of SBIRT training in residency programs nationwide. Training residents in SBIRT may increase the spread of this approach as residents complete training and implement best practices into their clinical practice. SAMHSA expects to establish SBIRT training as a component of residency programs in a variety of disciplines including family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, emergency medicine, surgery, psychiatry, and other programs.

We sought to describe the geographic distribution of SBIRT training programs, the major curricular features and delivery methods, targeted trainees, screening instruments used, most valued training resources, challenges encountered, and future directions.

Methods

The program directors from 4 SBIRT medical residency programs developed a survey instrument to characterize each SBIRT grantee according to (1) the medical discipline(s) represented; (2) the number of residents trained to date; (3) the projected number of residents trained during the grant period; (4) characteristics curricula and delivery methods; (5) methods of assessing resident proficiency; and (6) use of the curriculum to train other health care professionals. The survey (provided as online supplemental material (818.2KB, pdf) ) was e-mailed to each participating program director and placed in an online application (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The survey collected general descriptive statistics, frequencies, and comments. Additional data for the number of participating residents were obtained from SAMHSA summary of grantees biannual report data reported in June 2011. The University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved this study.

Results

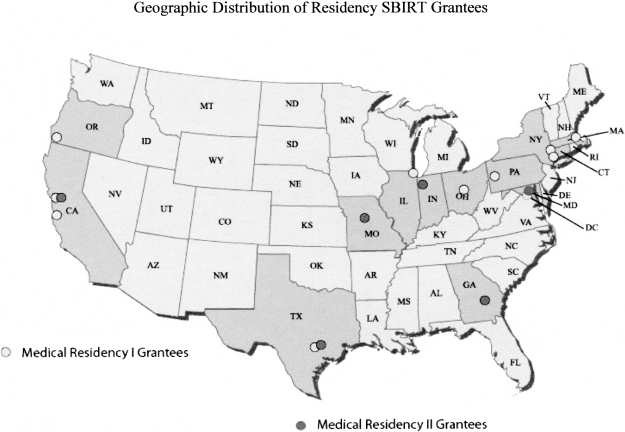

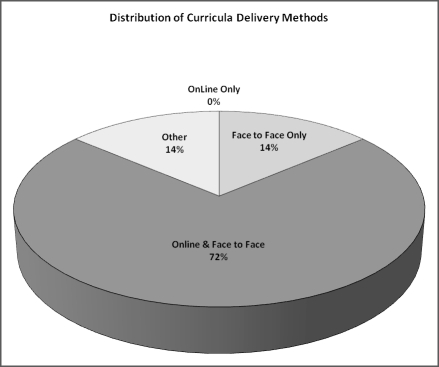

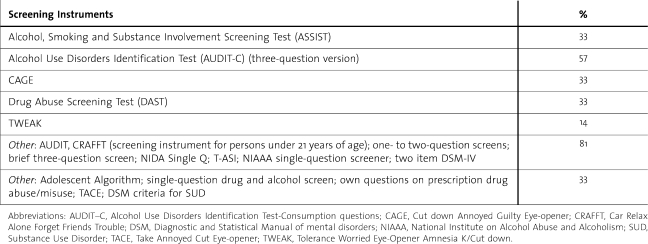

All 17 grantees responded to the online survey. figure 1 shows respondents' geographic distribution. All grantees have developed formal curricula; major curricular features are shown in box 2, and figure 2 displays the distribution of methods used to deliver the curricula. The table shows the screening instruments used with SBIRT. All programs incorporated some form of motivational interviewing into their curriculum. Motivational interviewing is a highly effective, evidence-based approach often used to assist patients in changing unhealthy behaviors.15–18 Motivational interviewing skills taught include open-ended questions, affirming patient self-efficacy, reflective listening, summarization, developing discrepancy, rolling with resistance, and a specific intervention approach developed for emergency departments called the Brief Negotiated Interview.19

FIGURE 1.

Geographic Distribution of Residency SBIRT Grantees

Box 2 Major Curricula Features

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and addiction

Curricular adjustments for different specialties

Definitions of substance abuse and dependence

Brief intervention approaches

Addiction as a chronic disease

Clinical skills evaluation

Community focus

Confidence ruler

Cultural awareness

Drinker's pyramid

Impaired physicians/residents

Motivation for change/motivational enhancement skills/motivational interviewing

Neurobiology of addiction

Overview of the public health issues associated with hazardous alcohol and drug use

Pain management

Pharmacologic treatment of addictive disorders

Precepting SBIRT (for faculty/resident champion training)

Prescription drug abuse

Referral to treatment approaches

SBIRT implementation approaches

Screening tools

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of Curricula Delivery Methods

TABLE.

Screening Instruments and Percentage Use

Sixteen grantees are currently training postgraduate year-2 (PGY-2) and PGY-3 residents, and 15 of the 17 are training PGY-1 residents. All programs train residents from multiple specialties (box 3). As of June 2011, 2867 residents have been trained across the 17 grantees, and program directors report that 100% of trained residents are using SBIRT in practice. In addition to monthly resident self-reports of having used SBIRT during the past month, measures of the use of SBIRT in practice include chart reviews, procedural logs, and tracking forms. Ten grantees use the SBIRT curriculum to educate medical students, and an additional 4 grantees plan to do so. Other health care personnel who are being trained include clinical pharmacists, front desk staff, counselors, medical assistants, nurses, nurse practitioners, physical therapists, physician assistants, social workers, chaplains, physician assistant students, nurse midwives, psychologists, and health care educators. Training resources that are reported to be most valuable included standardized patient encounters, the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Clinician's Guide,20 the Georgia-Texas Improving Brief Intervention Project modules,21 the validated screening tools listed in the table, and billing and coding information.22

Box 3 Medical Specialties of Participating Residents (Number of Programs Providing Training in This Area)

Anesthesiology (1)

Emergency Medicine (7)

Family Medicine (15)

Infectious Disease (1)

Internal Medicine (14)

Obstetrics and Gynecology (10)

Pediatrics (12)

Podiatry (1)

Preventive Medicine (2)

Psychiatry – Adult and Child (10)

Surgery – including Oral Maxillofacial, Trauma (4)

The most consistently mentioned challenge to developing and implementing an SBIRT curriculum is finding time in residents' schedules to deliver the modules, both online and face-to-face. Other reported challenges included (1) the need for additional trained faculty and resident role models; (2) development of assessment methods to reliably document resident competence in performing SBIRT; (3) maintaining a focus on delivering SBIRT as a preventive service for at-risk drinkers while also identifying patients with substance use disorders; (4) disseminating SBIRT outside the 17 participating programs (box 1); and (5) finding ways to sustain SBIRT training efforts after federal funding ends.

Box 1 Participating Medical Residency Programs

Access Community Health Network

Albany Medical Center

Baylor College of Medicine InSight SBIRT Residency Training Program

Boston University Combined Residency Program in Pediatrics

Howard University SBIRT Medical Residency Program

Indiana University

Kettering Medical Center

Mercer University School of Medicine

Oregon Health and Science University Family Medicine Residency

Natividad Medical Center

University of California, San Francisco – San Francisco General Hospital

University of California, San Francisco – Department of General and Internal Medicine

University of Maryland

University of Missouri Health Care

University of Pittsburgh SMaRT Program

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio-Pediatric Residency

Yale University Emergency Medicine

Discussion

Screening and brief intervention for alcohol abuse has been found to be one of the most underutilized effective prevention interventions in primary care.23 Similarly, substance use disorder teaching is one of the most neglected areas in American medical education, resulting in a recent “call to action” issued by a consensus statement sponsored by the Betty Ford Institute and the Obama administration.24 Our survey results demonstrate significant successes of the residency SBIRT initiative in mobilizing medical schools and teaching hospitals to offer curricula on alcohol and drug misuse in residency programs across the country during the study period (2008–2011), and 2867 residents in 11 different medical specialty areas receiving training thus far. In addition, health professionals in 9 other disciplines and medical students have been trained in the initial 2 years of this project, although training non-physician professionals was not part of the project's original mandate. Participants use state-of-the art training approaches that go beyond simple lectures and online modules to providing active learning exercises and skills training, which have been shown to be effective,25 and use state-of-the-art screening and intervention approaches, employing validated instruments such as the AUDIT,26 AUDIT-C, DAST, CRAFFT, 27 and ASSIST28 and using evidence-based intervention approaches such as motivational interviewing to assist patients with alcohol and drug misuse. SBIRT training is helping residency programs provide training that meets several of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies. Findings suggest that SBIRT skills are being used in clinical settings, and training programs using a variety of means for measuring the use of SBIRT in practice report that 100% of their residents are using SBIRT clinically.

Consistent provision of preventive clinical services, such as SBIRT, in US primary care has proven to be a challenging enterprise in light of the many competing demands, and historically, only limited numbers of practices have achieved high levels of preventive service delivery after undergoing intensive, highly individualized interventions.29 Additional challenges include dissemination and sustainability. In order to become an effective public health intervention, SBIRT must spread beyond the 17 participating institutions to create a true nationwide impact. Responses of participating programs indicated that many are relying on the posting of their materials on the Internet to disseminate SBIRT teaching and training. Given the history of curricular inertia in substance misuse disorder teaching,30,31 the success of this approach remains to be demonstrated. In addition, significant numbers of expert faculty members will be needed to disseminate these techniques outside the 17 participating institutions,4 and the community will need to train more faculty in SBIRT. Finally, the residency SBIRT initiative will face the challenges encountered by other similar grant-funded projects, that is, the ability to sustain efforts after outside funding ends. The major limitation of this study is that most information is based on self-reports and is subject to all the limitations of that data collection method.

Conclusions

The SBIRT initiative has resulted in rapid increases in the implementation of training programs to train residents and other health care personnel how to screen, provide brief interventions for patients exhibiting unhealthy alcohol and/or drug use, and refer seriously ill patients to substance use disorder treatment. The few years should see expansion in teaching and training as federal funding continues and more health care sites implement SBIRT. While validated screening tools are available for conducting SBIRT, there are no validated assessment tools for evaluating SBIRT competency. This is an area of active investigation and is needed for SBIRT training to integrate successfully into increasingly competency-based curricula. Current grantees should disseminate SBIRT teaching to other residencies in their areas while seeking to secure funding for a national faculty development effort to facilitate more rapid dissemination. In the absence of these efforts, program dissemination and sustainability after grant funding ends are likely to be ongoing challenges for this program.

Footnotes

Janice L. Pringle, PhD, is Associate Professor and Director of the Program Evaluation Research Unit, University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy; Alicia Kowalchuk, DO, is Assistant Professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Medical Director of the InSight Program, Harris County Hospital District, and Medical Director of the CARE Clinic Santa Maria Hostel; Jessica Adams Meyers, MSEd, is Project Coordinator, Program Evaluation Research Unit, University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy; and J. Paul Seale, MD, is Professor and Director of Research, Department of Family Medicine, Medical Center of Central Georgia and Mercer University School of Medicine.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

The authors acknowledge the Substance Abuse Mental Health Service Administration and Kevin Hylton of JBS International/Alliances for Quality Education, Inc.

References

- 1.Solberg LI, Maciosek MV, Edwards NM. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse: ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohman TM, Kulkarni S, Waters V, Spence RT, Murphy-Smith M, McQueen K. Assessing health care organizations' ability to implement screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. J Addict Med. 2008;2:151–157. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181800ae5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitlock EP, Polen MR, Green CA, Orleans T, Klein J for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce risky/harmful alcohol use by adults: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:557–568. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madras BI, Compton WM, Avula D, Stegbauer T, Stein JB, Clark HW. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1–3):280–295. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleming MF, Mundt MP, French MT, Manwell LB, Stauffacher EA, Barry KL. Brief physician advice for problem drinkers: long-term efficacy and benefit-cost analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(1):36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zernig G, Saria A, Kurz M. Handbook of Alcoholism. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien P, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertens JR, Weisner C, Ray GT, Fireman B. Hazardous drinkers and drug users in HMO primary care: prevalence, medical conditions, and costs. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:989–998. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000167958.68586.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson K, Bendtsen P, Akerlind I. Early intervention for problem drinkers: readiness to participate among general practitioners and nurses in Swedish primary health care. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:38–42. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasswell AB, Liepman MR, McQuade WH, Wolfson MA, Levy SM. Comparison of primary care residents' confidence and clinical behavior in treating hypertension versus treating alcoholism. Acad Med. 1993;68:580–582. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199307000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaner EF, Heather N, McAvoy BR, Lock CA, Gilvarry E. Intervention for excessive alcohol consumption in primary health care: attitudes and practices of English general practitioners. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:559–566. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.4.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deehan A, Templeton L, Taylor C, Drummond C, Strang J. Low detection rates, negative attitudes and the failure to meet the “Health of the Nation” alcohol target: findings from a national survey of GPs in England and Wales. Drug Alcohol Rev. 1998;17:249–258. doi: 10.1080/09595239800187081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roche AM, Richard GP. Doctors' willingness to intervene in patients' drug and alcohol problems. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90010-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rush BR, Powell LY, Crowe TG, Ellis K. Early intervention for alcohol use: family physicians' motivations and perceived barriers. CMAJ. 1995;152:863–869. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker A, Hambridge J. Motivational interviewing: enhancing engagement in treatment for mental health problems. Behav Change. 2002;19:138–145. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rollnick SP, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational Interviewing in Health Care: Helping Patients Change Behavior (Applications of Motivational Interviewing) New York: The Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative. The impact of screening, brief intervention and referral for treatment on emergency department patients' alcohol use. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50(6):699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.06.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician's guide. National Institutes of Health, 2005. http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/cliniciansguide2005/guide.pdf. January 26, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seale JP, Shellenberger S, Clark DC. Providing competency-based family medicine residency training in substance abuse in the new millennium: a model curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:33. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisconsin Initiative to Promote Healthy Lifestyles. Coding, billing and reimbursement manual. http://www.wiphl.com/bills/index.php?category_id=4648. Accessed November 11, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maciosek MV, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Flottemesch TJ, Goodman MJ, Solberg LI. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O'Connor PG, Nyquist J, McLellan AT. Integrating addiction medicine into graduate medical education in primary care: the time has come. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:56–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.el-Guebaly N, Toews J, Lockyer J, Armstrong S, Hodgins D. Medical education in substance-related disorders: components and outcome. Addiction. 2000;95:949–957. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95694911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knight JR, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Chang G. Validity of brief alcohol screening tests among adolescents: a comparison of AUDIT, POSIT, CAGE and CRAFFT. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;27:67–73. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000046598.59317.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Humeniuk SL, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of alcohol, smoking, and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST) Addiction. 2008;103(6):1039–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery: the study to enhance prevention by understanding practice (STEP-UP) Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:20–28. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00310-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Isaacson JH, Fleming M, Kraus M, Kahn R, Mundt M. A national survey of training in substance use disorders in residency programs. J Stud Alcohol. 2000;61:912–915. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleming MF, Manwell LB, Kraus M, Isaacson JH, Kahn R, Stauffacher EA. Who teaches residents about the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders? A national survey. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:725–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]