Abstract

Cognition has already been considered as a component of frailty, and it has been demonstrated that it is associated with adverse health outcomes. We estimated the prevalence of frailty syndrome in an Italian older population and its predictive role on all-cause mortality and disability in nondemented subjects and in demented patients. We evaluated 2,581 individuals recruited from the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging, a population-based sample of 5,632 subjects, aged 65–84 years old. Participants received identical baseline evaluation at the 1st survey (1992–1993) and were followed at 2nd (1995–1996) and 3rd survey (2000–2001). A phenotype of frailty according to partially modified measurement of Cardiovascular Health Study criteria was operationalized. The overall prevalence of frailty syndrome in this population-based study was 7.6% (95% confidence interval (CI) 6.55–8.57). Frail individuals noncomorbid or nondisable were 9.1% and 39.3%, respectively, confirming an overlap but not concordance in the co-occurrence among these conditions. Frailty was associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality over a 3-year follow-up (hazard ratio (HR) 1.98, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.52–2.60) and over a 7-year follow-up (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.44–2.16), but with significant increased risk of disability only over a 3-year follow-up (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.06–1.86 over a 3-year follow-up and HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.88–1.56 over a 7-year follow-up). Frail demented patients were at higher risk of all-cause mortality over 3- (HR 3.33, 95% CI 1.28–8.29) and 7-year follow-up periods (HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.10–3.44), but not of disability. Frailty syndrome was a short-term predictor of disability in nondemented older subjects and short- and long-term predictor of all-cause mortality in nondemented and demented patients.

Keywords: Frailty, All-cause mortality, Dementia, Disability, Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Frailty has emerged as an increasingly important concept in both clinical care of older persons and research in aging and as a clinical syndrome generally associated with a greater risk for adverse outcomes such as falls, disability, institutionalization, and death (Fried et al. 2001; Rockwood et al. 2004). The Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) index developed by Fried et al. (2001) is an operational definition of frailty in older subjects based on the presence of any three of the following five characteristics: shrinking, weakness, poor endurance, slowness, and low physical activity. While other population-based studies confirmed original findings from the CHS of the overlaps and dissociations among frailty, disability, and comorbidity, there were important differences in the reported prevalence estimates (from 6.9% to 20.0%; Fried et al. 2001; Woods et al. 2005; Ottenbacher et al. 2005; Bandeen-Roche et al. 2006; Cesari et al. 2006; Gill et al. 2006; Hirsch et al. 2006; Avila-Funes et al. 2008; Santos-Eggimann et al. 2009; Wong et al. 2010).

Although the CHS index remains the most widely used, inclusion of other common age-related conditions has been a topic of considerable debate (Panza et al. 2011). Furthermore, several studies have reported that physical frailty is associated with low cognitive performance (Gill et al. 1996; Strawbridge et al. 1998, Avila-Funes et al. 2009), incidence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD; Buchman et al. 2007), and mild cognitive impairment (Boyle et al. 2010) and AD pathology in older persons with and without dementia (Buchman et al. 2008). At present, there is no population-based study in which frailty syndrome has been investigated as possible determinant of short- and long-term all-cause mortality in demented patients. In the present study, we estimated the prevalence of frailty syndrome in a large Italian older population and its predictive role on all-cause mortality and disability in nondemented subjects and demented patients.

Methods

Setting

The methods of the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA) and the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd survey data collection have been described in detail elsewhere (Solfrizzi et al. 2004, 2006). A sample of 5,632 subjects aged 65–84 years, free-living or institutionalized, was randomly selected from the electoral rolls of eight Italian municipalities after stratification for age and gender. Following the equal allocation strategy, in each study center, four age classes (65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, and 80 to 84 years old) of 88 subjects for each gender were drawn up. The data of the present report have been obtained during the first prevalence survey study between March 1992 and June 1993 (prevalence day: March 1, 1992), the 2nd prevalence survey study between September 1995 and October 1996 (prevalence day: September 1, 1995), and the 3rd prevalence survey between March 2000 and September 2001 (prevalence day: March 1 2000). The study project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the eight municipalities. Voluntary informed consent was obtained from each subject and/or their relatives before enrollment.

Clinical examination and laboratory analyses

Cases of coronary artery disease (myocardial infarction or angina pectoris), type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and peripheral artery disease were identified with a two-phase procedure, utilizing clinical criteria described in detail elsewhere (Solfrizzi et al. 2004; The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging Working Group 1997). Each participant was administered a screening questionnaire, a series of brief screening tests to identify suspect cases of the above listed diseases for further investigation, and a clinical evaluation (phase 1). Suspected cases were clinically confirmed with a standardized clinical examination by a certified neurologist or geriatrician (phase 2). In particular, the main screening criteria for cognitive impairment or dementia were the Mini Mental State examination (MMSE) with a cutoff score of 23 (Folstein et al. 1975), or a previous diagnosis reported by the respondent proxy. The diagnosis was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd edition revised criteria for dementia syndrome (American Psychiatric Association 1987), the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke–Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association criteria for possible and probable AD (McKhann et al. 1984), and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision criteria for vascular dementia (VaD), and other dementing diseases (World Health Organization 1992).

Body mass index was calculated as weight/square height (kilograms per square meter). Based on self-reports, smoking habits were categorized as “ever” or “never.” Furthermore, smoking habits were assessed by asking the study participants the amount of cigarettes smoked and the ages when they started and stopped smoking. Using these data, we obtained the variable “pack-years” (years smoked × usual number of cigarettes smoked/20 cigarettes per pack). Depressive symptoms were investigated using the Italian version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)-30 items (Yesavage et al. 1982–1983). Functional status was assessed with the Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale, which determines the level of independence in six activities: bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring from bed to chair, continence, and feeding (Katz and Akpom 1976). Ability in home management (using the telephone, shopping for personal items, preparing meals, doing light housework, managing money or drugs, and so forth) was assessed by the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) scale (Lawton and Brody 1969).

The physical activity practice was assessed by the administration of a structured questionnaire specifically developed for the InChianti Study and also proposed for the ILSA, ascertaining retrospectively physical activities, plus frequency and duration (Benvenuti et al. 2000). Levels of physical activity in the year before the interview were coded into an ordinal scale as follows: 1, hardly any physical activity; 2, mostly sitting (occasional walks, easy gardening); 3, light exercise (no sweating) 2–4 h/week; 4, moderate exercise (sweat) 1–2 h/week; 5, moderate exercise >3 h/week; 6, intense exercise (at the limits) >3 times/week. According to this classification, we grouped the participants as follows: 1–3, inactive or light physical activity; 4–5, moderate physical activity; and 6, intense physical activity (Benvenuti et al. 2000). Physical function was also ascertained prospectively also with ADL and IADL tasks, as well as the GDS item: “Do you practice physical activity?” (Yesavage et al. 1982–1983). Motor performance was assessed using the six tests of a battery designed to measure motor ability in older people (standing up from a chair, stepping up, tandem walk, standing on one leg, walking speed, and steps turning 180°; Inzitari et al. 2006). The Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), a weighted index that takes into account the number and the seriousness of comorbid disease, was calculated (Charlson et al. 1987). Data on vital status were gathered directly from study participants or proxy responders. Death certificates were collected for those who died. The date and cause of death for all participants who died were obtained from death certificates and other official sources, and trained physicians coded the cause of death according to the International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision. Blood samples were obtained early in the morning after a 13-h overnight fast. Serum albumin was measured by electrophoresis, as detailed elsewhere (Maggi et al. 2001).

Operationalization of the frailty syndrome

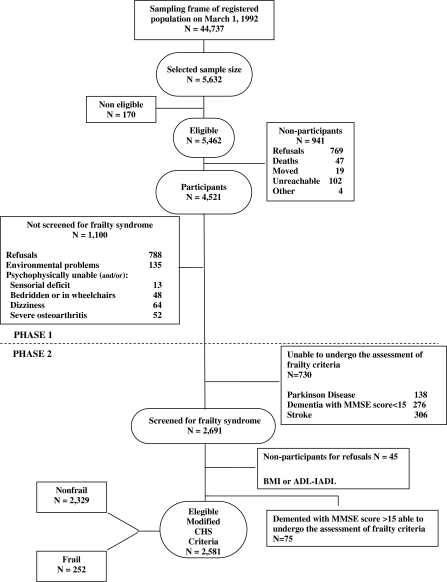

A phenotype of frailty was operationalized slightly modifying the CHS criteria (Fried et al. 2001) and was identified by the presence of three or more frailty components, as shown in Table 1. For the second component (“exhaustion”), we included only the demented patients with a MMSE score ≥15 because the use of the GDS has been validated within this MMSE score limit (Table 1; Mcgivney et al. 1996). We excluded at baseline both for the outcome all-cause mortality and the outcome disability older subjects with severe sensorial deficit, bedridden or in wheelchairs, dizziness, severe osteoarthritis, a history of Parkinson's disease, stroke, dementia, or MMSE score <15, as these conditions could potentially constitute frailty components as a consequence of a single disease (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Characterization of frailty syndrome (Cardiovascular Health Study modified criteria) (Fried et al. 2001)

| Components of frailtya | ILSA measurements |

|---|---|

| Weight loss | Unintentional weight loss >5 kg in the last year (possibly supported by the answer to the question: “Do you think that your clothes are wide?”) |

| Exhaustion | GDS score ≥10 and negative answer to the question: “Do you feel full of energy?” |

| Weaknessb | Negative chair-stand test: inability to stand from a chair unaided and without using the arms (standardized by gender and body mass index)e |

| Slownessc | Time ≥7 s spent to walk 5 m (standardized by gender and height)e |

| Low activityd | Physical activity questionnaire: inactive or light physical activity (retrospective evaluation) or asking “Do you practice physical activity?” (prospective evaluation; standardized by gender) |

ILSA Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging, GDS Geriatric Depression Scale, a score of less than 10 indicates absence of depression, between 10 and 19 mild depression, and greater than 20 to a maximum of 30 severe depression

aPositive for phenotype of frailty syndrome: presence of ≥3 criteria

bMen 66/101 and women 97/151 frail individuals, χ2 = 0.56, p = 0.46

cMen 53/101 and women 72/151 frail individuals, χ2 = 0.03, p = 0.86

dMen 98/101 and women 140/151 frail individuals, χ2 = 2.15, p = 0.14; as overly conservative measure of agreement between prospective and retrospective measurements for low activity was used Cohen’s kappa (Cohen’s kappa = 0.12, p < 0.01)

eTest included in the Motor Performance battery of the ILSA (Benvenuti et al. 2000)

Fig. 1.

Attrition of the study population at the different phases of the survey, Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 1992–1993. BMI body mass index, ADL Activities of Daily Living, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, CHS Cardiovascular Health Study

Statistical analysis

The prevalence estimates of frailty syndrome were based on baseline data collected in the 1st ILSA survey. A poststratification adjustment by age and gender was used to make the sample consistent with the population represented. Prevalence punctual estimates (and 95% confidence interval (CI)) were evaluated according to the procedures of complex surveys supported by SAS package (SURVEYMEANS procedure) on the basis of the characteristics of the ILSA sampling. Trends in binomial proportions of frailty syndrome across levels of age, disability, and by gender were evaluated by Cochrane–Mantel–Haenszel test. Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the independent contribution of baseline frailty syndrome to incidence of all-cause mortality and disability (worsening in ADL score ≥1) over 3-year (median duration of follow-up was 3.4 years) and over 7-year follow-ups (median duration of follow-up was 7.6 years). Indicators for being frail (three or more frailty criteria) were established with the at-risk or nonfrail group (less than three frailty criteria) serving as the reference group. Partially adjusted hazard models (adjustment for 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, and 80–84 age categories and gender) were estimated for each outcome. Fully adjusted hazard models were also fit; using baseline covariates could be predictive of mortality and disability in this cohort: age categories (coded 1 for 65–69, coded 2 for 70–74, coded 3 for 75–79, and coded 4 for 80–84), gender (coded 0 for women and 1 for men), education, pack-years (coded 0 for pack-years cigarettes = 0 (never smoking), and 1 for pack-years cigarettes ≥0.5), IADL score, MMSE, CCI, and serum albumin levels. The same procedure was repeated in the demented participants followed up over 3 years (median duration of follow-up was 3.4 years both disability and all-cause mortality) and over 5 years (median duration of follow-up was 5.1 years both disability and all-cause mortality). Fully adjusted hazard models were also fit, using baseline covariates as in the previous paragraph excluding MMSE and IADL scores involved in the diagnosis of dementia. To check the proportional hazard assumption over time, we included each covariate by time as a predictor variable in the statistical models. Finally, we defined the time to event of interest beginning at the time the subject entered the study. Analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, 2004). The statistical significance threshold was set at 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of individuals with frailty and without frailty syndrome are shown in Table 2. Figure 1 shows sample size and attrition of the present study, with frailty syndrome diagnosed according to the CHS criteria in 252 of 2,851 (7.6%) individuals. Differences in age (73.1 ± 5.6 vs 75.3 ± 5.7, p < 0.01 evaluated by separate variance t test) and gender (Pearson χ2 = 43.9, p < 0.01) were observed between participants and nonparticipants (2,581 participants—1,414 (54.8%) men and 1,167 women (45.2%); 3,051 nonparticipants—1,401 (45.9%) men and 1,650 (54.1%) women). Some frailty components (weakness, slowness, and low activity) were not measured according to the CHS instruments of evaluation, but they were slightly modified with similar measurements used in the ILSA (Table 1). Individuals who were frail, were older, more likely to be women, had less education, and higher rates of comorbid chronic diseases and disability than those who were nonfrail (p < 0.001 for each comparison; Table 2). Both lower cognition and greater depressive symptoms were associated with frailty. Frail demented subjects were 17.8%, frail individuals without disability were 39.3%, and without comorbidity were 9.1%.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics (mean ± SD or median (25th–75th percentiles) or %) of individuals with frailty and without frailty syndrome

| Variable | Total sample (n = 2,581) | Nonfrail (n = 2,329) | Frail (n = 252) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 73.1 ± 5.6 | 72.6 ± 5.5 | 77.2 ± 4.7 | 0.001a |

| Women (%) | 1,166 (45.2) | 1,015 (43.6) | 151 (59.9) | 0.001b |

| Education (years) | 6.3 ± 4.6 | 6.6 ± 4.7 | 4.2 ± 3.4 | 0.001a |

| MMSE | 25.8 ± 4.3 | 26.2 ± 3.9 | 23.2 ± 4.8 | 0.001a |

| ADL | ||||

| 0 lost functions (%) | 1,863 (72.2%) | 1,764 (75.7%) | 99 (39.3%) | 0.001b |

| 1–2 lost functions (%) | 599 (23.2%) | 512 (22%) | 87 (34.5%) | 0.001b |

| ≥2 lost functions (%) | 119 (4.6%) | 53 (2.3) | 66 (26.2%) | 0.001b |

| IADL | 8.8 ± 3.4 | 8.4 ± 3.4 | 12.5 ± 6.4 | 0.001a |

| GDS | 9.5 ± 6.1 | 8.8 ± 5.7 | 16.4 ± 5.8 | 0.001a |

| Hypertension | 1,789 (69.3%) | 1,582 (67.9%) | 207 (82.1%) | 0.001b |

| Coronary artery disease | 322 (12.5%) | 284 (12.2%) | 38 (15.1%) | 0.188b |

| Congestive heart failure | 155 (6.0%) | 127 (5.5%) | 28 (11.1%) | 0.001b |

| Peripheral artery disease | 156 (6%) | 133 (5.7%) | 23 (9.1%) | |

| Type two diabetes mellitus | 330 (12.8%) | 290 (12.5%) | 40 (15.9%) | 0.122b |

| CCI | 1.0 ± 0.79 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 0.001a |

| Pack-years cigarettes (25°, 50°, 75° percentiles) | 17.1 ± 26.4 (0, 0.6, 26.7) | 17.6 ± 26.5 (0, 1.5, 30) | 13.0 ± 25.9 (0, 0, 14.9) | 0.001c |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.5 | 0.001a |

The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 1st prevalence survey, 1992–1993

MMSE Mini Mental State Examination, ADL Activities of Daily Living, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, GDS Geriatric Depression Scale, CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index

aStudent’s t test for unpaired data

bPearson’s chi-squared

cMann–Whitney U test

Frailty syndrome prevalence estimates

The prevalence rate of frailty syndrome in this study population was 7.56% (95% CI 6.55–8.57). It increased with class of age (Mantel–Haenszel estimate, odds ratio (OR) 2.12, 95% CI 1.88–2.38), was higher in women than in men (Mantel–Haenszel estimate, OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.48–2.52), and increased with class of age more in men than in women, but the difference in increase was not significant (Mantel–Haenszel estimate, OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.81–2.47 for women and Mantel–Haenszel estimate, OR 2.14, 95% CI 1.78–2.58, test of homogeneity of ORs χ2 = 0.01, p < 0.91). Moreover, the prevalence of frailty syndrome increased with worsening in ADL score (Mantel–Haenszel estimate, OR 2.12, 95% CI 5.56–8.86), while it increased not significantly with age by worsening in ADL score (Mantel–Haenszel estimate, OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.75–2.58, OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.29–1.96, and OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.32–2.77, test of homogeneity of ORs 4.06, χ2 = 4.06, p < 0.13; Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence rates (with 95% confidence intervals) of frailty syndrome in nondemented individuals, according to age classes, gender, and self-reported disability

| Age class, years | Gender | Lost functions in ADL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men, n = 1,415 | Women, n = 1,166 | ADL 0, n = 1,861 | ADL 1–2, n = 599 | ADL >2, n = 121 | Total rate, n = 2,581 | |

| 65–69 | 1.82 (0.56–3.08) | 2.50 (1.01–3.99) | 1.28 (0.44–2.12) | 4.76 (1.01–8.52) | 28.35 (0.08–55.88) | 2.19 (1.20–3.18) |

| 70–74 | 3.94 (2.05–5.84) | 7.45 (4.52–10.38) | 4.00 (2.34–5.66) | 8.58 (3.64–13.52) | 37.72 (16.63–58.80) | 5.82 (4.06–7.57) |

| 75–79 | 10.44(7.05–13.83) | 18.70 (14.0–23.40) | 9.76 (6.58–12.93) | 19.39 (13.54–25.23) | 41.79 (25.12–58.45) | 14.86 (11.88–17.84) |

| 80–84 | 15.59(10.93–20.25) | 26.77 (20.29–33.26) | 11.63 (7.47–15.80) | 23.41 (14.96–31.86) | 75.64 (64.01–87.27) | 22.19 (17.85–26.54) |

| Total | 5.25 (4.16–6.34) | 9.49 (7.84–11.15) | 4.09 (3.22–4.95) | 12.81 (9.93–15.70) | 49.95 (40.39–59.52) | 7.56 (6.55–8.57) |

The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 1st survey, 1992–1993

ADL Activities of Daily Living

Frailty syndrome, all-cause mortality, and disability in nondemented individuals

During the first follow-up period, 8,692 person-years were accrued (out of 2,581 elderly individuals, 258 refused to participate, 32 moved, and 88 were unreachable), and 369 deaths occurred, whereas at the second follow-up 16,613 person-years were accrued (out of 2,212 elderly individuals, 20 moved, and 52 were unreachable), and 782 events of death in overall occurred. In frail individuals identified at baseline, mortality was about two times higher than that for the nonfrail over a 3-year follow-up (HR 1.98, 95% CI 1.52–2.60), while over a 7-year follow-up, it was about 1.7 times higher than that for the not frail (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.44–2.16, fully adjusted model; Table 4).

Table 4.

Frailty syndrome and risk of disability and all-cause mortality in nondemented individuals and demented patients

| Surveys | New events | Total subjects | Partially adjusteda | Fully adjustedb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |||||

| Disability (worsening of functions in ADL ≥1) | Nondemented individuals | 1992–1993 | 379 | 2,193 | 1.45 | 1.18–2.01 | 1.32 | 1.06–1.86 |

| 1995–1996 | ||||||||

| Nondemented individuals | 1992–1993 | 546 | 2,121 | 1.27 | 0.95–1.52 | 1.16 | 0.88–1.56 | |

| 2000–2001 | ||||||||

| All-cause mortality | Nondemented individuals | 1992–1993 | 369 | 2,193 | 2.82 | 1.68–3.51 | 1.98 | 1.52–2.60 |

| 1995–1996 | ||||||||

| Nondemented individuals | 1992–1993 | 782 | 2,121 | 2.11 | 1.76–2.53 | 1.74 | 1.44–2.16 | |

| 2000–2001 | ||||||||

| Disability (worsening of functions in ADL ≥1) | Demented patients | 1992–1993 | 19 | 75 | 1.36 | 0.54–3.56 | 1.84 | 0.54–6.31 |

| 1995–1996 | ||||||||

| Demented patients | 1992–1993 | 21 | 75 | 1.30 | 0.53–3.11 | 1.28 | 0.41–3.43 | |

| 2000–2001 | ||||||||

| All-cause mortality | Demented patients | 1992–1993 | 43 | 75 | 2.51 | 1.28–4.93 | 3.33 | 1.29–8.29 |

| 1995–1996 | ||||||||

| Demented patients | 1992–1993 | 55 | 75 | 1.99 | 1.15–3.52 | 1.89 | 1.10–3.44 | |

| 2000–2001 | ||||||||

The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging, 2nd survey, 1995–1996 and 3rd survey, 2000–2001

ADL Activities of Daily Living, HR hazard ratios, CI confidence interval, IADL Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

aHRs were adjusted for age, sex (coded 0 for women and 1 for men), and failure type as covariate in partially adjusted models

bHRs were adjusted for age categories (coded 1 for 65–69, coded 2 for 70–74, coded 3 for 75–79, and coded 4 for 80–84), gender (coded 0 for women and 1 for men), education, pack-years {pack-years cigarettes [coded 0 for pack-years cigarettes = 0 (never smoking) and 1 for pack-years cigarettes ≥0.5]}, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living score, Mini Mental State Examination score, Charlson comorbidity index, serum albumin levels, in fully adjusted models for the nondemented population; MMSE and IADL scores were excluded from the models for the demented population

During the first follow-up period, 379 new events of disability occurred, while at the second follow-up 546 events of disability in overall occurred. Moreover, in those who met the criteria for frailty at baseline, occurring disability was significantly increased only over a 3-year follow-up (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.06–1.86 over a 3-year follow-up fully adjusted model), but not over a 7-year follow-up (HR 1.16, 95% CI 0.88–1.56 fully adjusted model; Table 4).

Frailty syndrome, all-cause mortality, and disability in demented subjects

Seventy-five demented patients who performed a MMSE score over 15 to make plausible GDS scores were able to undergo the assessment of frailty criteria. Thirty-eight (50.7%) were affected by AD, 16 (21.3%) by VaD, and 21 (28%) by other dementias. Fifty-two percent demented subjects were frail (47.4% AD, 28.9% VaD, and 23.7% other dementias). During the first follow-up period, 258 person-years were accrued, and 43 death occurred while at second follow-up period, 246 person-years were accrued and 55 events of death in overall occurred. Demented patients frail at baseline had a higher risk of all-cause mortality about three times than that for the nonfrail over a 3-year follow-up (HR 3.33, 95% CI 1.28–8.29, fully adjusted model). On the other hand, demented patients frail at baseline had a higher risk of all-cause mortality about two times than that for the nonfrail over a 7-year follow-up (HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.10–3.44, fully adjusted model; Table 4). During the first follow-up period, 19 new events of disability occurred, while at the second follow-up, 21 events of disability in overall occurred. Moreover, in those who met the criteria for frailty at baseline, occurring disability was not significantly increased over a 3-year follow-up (HR 1.84, 95% CI 0.54–6.31, fully adjusted model) and over a 7-year follow-up (HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.41–3.43, fully adjusted model; Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we found a prevalence rate of 7.6% (95% CI 6.55–8.57) for frailty syndrome in a community-defined cohort of 65–84-year-old subjects. In the nondemented sample, after adjustment for possible confounders at baseline, frailty syndrome remained an independent risk factor of all-cause mortality in short- and long-term periods and significantly associated with an increased risk of disability only in short-term period. Frail individuals noncomorbid or nondisable were 9.1% and 39.3%, confirming an overlap but not concordance in the co-occurrence among these conditions. Furthermore, frail demented patients were at higher risk of all-cause mortality but not of disability in short- and log-term periods.

In the ILSA sample, the prevalence of frailty syndrome, defined according the CHS criteria (Fried et al. 2001), was comparable to the overall prevalence of frailty reported in the CHS sample, which included people aged 65 years and over (6.9%; 95% CI 6.22–7.58), but the subsample of CHS participants aged 75 and over had a slightly higher prevalence of 13% (95% CI 11.5–14.7; Fried et al. 2001). However, frailty syndrome was associated with a higher risk of disability in the CHS over 3 and 7-year follow-ups (Fried et al. 2001), while in the ILSA, this risk was significant only over a 3-year follow-up. Furthermore, differences between the CHS and the ILSA populations in age range (involvement of 85+-year-old individuals in the CHS), gender distribution (45.2% of women in the ILSA vs. 57.9% in the CHS, with female gender that is more likely frail), and disability at baseline (ADL ≥1 in frail groups was 27.5% for the CHS and 60.7% for the ILSA) could be partly explain this different impact of frailty syndrome on disability. The prevalence estimate of frailty syndrome in the ILSA was also similar to that of another Italian population-based study, the Invecchiare in Chianti Study (8.8%; Cesari et al. 2006). However, several other population-based studies have applied the same definition of frailty syndrome of the CHS and the ILSA with very different prevalence estimates that varied from 6.9% to 20.0% (Fried et al. 2001; Woods et al. 2005; Ottenbacher et al. 2005; Bandeen-Roche et al. 2006; Gill et al. 2006; Hirsch et al. 2006; Avila-Funes et al. 2008; Wong et al. 2010). In these population-based studies, differences in the tools used in estimating the different components of the frailty syndrome, different races, and different age and gender distribution of the samples could be the source of this great variability.

To the best of our knowledge, the present was the first study in which frailty syndrome appeared to be a determinant of short- and long-term all-cause mortality in demented subjects. However, some of the frailty components have been associated with survival in demented subjects. In fact, long-term survivors among demented subjects had delayed emergence of motor symptoms (Hu et al. 2009), while unintentional weight loss was predictive of decreased survival in dementia (Aziz et al. 2008). Physical activity can reduce the risk of cognitive decline and dementia (Fratiglioni and Wang 2007), but clinical trial evidence for the effectiveness of physical activity programs in managing or improving cognition, function, behavior, depression, and mortality in people with dementia is still insufficient overall (Forbes et al. 2008). Furthermore, very recent findings from the Three-City Study suggested that cognitive impairment improved the predictive validity of the operational definition of frailty, increasing the risk to develop disability. On the contrary, risk of death also tended to be higher in cognitively impaired frail participants than in their nonfrail counterparts without cognitive impairment, even if the results were not statistically significant (Avila-Funes et al. 2009).

Previous epidemiological studies suggested that age, male sex, sociodemographic characteristics, the severity of dementia, other comorbid conditions, disability, and genetic characteristics may be significant predictors of mortality in the elderly population with dementia (Larson et al. 2004; Xie et al. 2008). In a previous report, we demonstrated that the Multidimensional Prognostic Index, derived from a standardized comprehensive geriatric assessment, was effective in predicting short- and long-term mortality risk in elderly subjects with dementia admitted to a geriatric hospital ward (Pilotto et al. 2009). Overall taken together, these findings supported the concept that considering multidimensional aggregate information and frailty syndrome could be very important for predicting short- and long-term all-cause mortality in older subjects with dementia and that it may be important for the identification of the more adequate management of patients.

The strengths of the present study were its prospective design, the lengths of the follow-up, the population-based setting, and its large number of subjects, although the number of dementia cases considered for all-cause mortality was relatively small (in overall 75 demented subjects). Nonetheless, some limitations in this study have to be considered. The HRs for all-cause mortality and disability were likely underestimated, as they did not include those who were not valuable for frailty at follow-up due to missing data or, for disability only, did not include loss due to mortality. Furthermore, excluding subjects with MMSE <15 to increase reliability of GDS responses would have led to underestimates of all-cause mortality. However, excluding “exhaustion” from the definition of frailty, the sample of frail demented subjects was reduced of only six individuals, and the results on increased all-cause mortality in this subsample did not change (data not showed). The results of the study were based on a retrospective assessment of frailty because this was not initially part of the study design. Physical activity was partially prospectively and partially retrospectively evaluated, and the agreement was relatively low. Notwithstanding these limitations, this study gave prevalence estimates in line with other population-based studies on older population. This was one of the priorities assigned to the CHS criteria for the phenotype of frailty when it was developed (Fried et al. 2001). Regardless of the tool used, frailty is a common syndrome, even though demented subjects who were the most frail might have been excluded from the denominator of population at risk (demented who performed MMSE <15). Although these promising findings, further investigations are needed in larger samples of elderly subjects with longer follow-up to determine the role of frailty syndrome in survival in demented subjects also in relation to other environmental and genetic factors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (Italian National Research Council—CNR-Targeted Project on Ageing—Grants 9400419PF40 and 95973PF40) and by the Ministero della Salute, IRCCS Research Program 2009–2011, Line 2: “Malattie complesse.” The researchers operate independently of the funders of the study.

Footnotes

The ILSA Working Group

E. Scafato, MD (Scientific Coordinator), G. Farchi, MSc, L. Galluzzo, MA, C. Gandin, MD, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Rome; A. Capurso, MD, F. Panza, MD, PhD, V. Solfrizzi, MD, PhD, V. Lepore, MD, P. Livrea, MD, University of Bari; L. Motta, MD, G. Carnazzo, MD, M. Motta, MD, P. Bentivegna, MD, University of Catania; S. Bonaiuto, MD, G. Cruciani, MD, D. Postacchini, MD, Italian National Research Centre on Aging, Fermo; D. Inzitari, MD, L. Amaducci, MD, University of Firenze; A. Di Carlo, MD, M. Baldereschi, MD, Italian National Research Council, Firenze; C. Gandolfo, MD, M. Conti, MD, University of Genova; N. Canal, MD, M. Franceschi, MD, San Raffaele Institute, Milan; G. Scarlato, MD, L. Candelise, MD, E. Scapini, MD, University of Milano; F. Rengo, MD, P. Abete, MD, F. Cacciatore, MD, University of Napoli; G. Enzi, MD, L. Battistin, MD, G. Sergi, MD, G. Crepaldi, MD, University of Padova; S. Maggi, MD, N. Minicucci, MD, M. Noale, MD, Italian National Research Council, Aging Section, Padova; F. Grigoletto, ScD, E. Perissinotto, ScD, Institute of Hygiene, University of Padova; P. Carbonin, MD, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome.

Contributor Information

Vincenzo Solfrizzi, Phone: +39-80-5473685, FAX: +39-80-5478633, Email: v.solfrizzi@geriatria.uniba.it.

Francesco Panza, Email: geriat.dot@geriatria.uniba.it, Email: f.panza@operapadrepio.it.

References

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd edn, revised (DSM-III-R) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Funes JA, Helmer C, Amieva H, Barberger-Gateau P, Goff M, Ritchie K, Portet F, Carrière I, Tavernier B, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Dartigues JF. Frailty among community-dwelling elderly people in France: the Three-City Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:1089–1096. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Funes JA, Amieva H, Barberger-Gateau P, Goff M, Raoux N, Ritchie K, Carrière I, Tavernier B, Tzourio C, Gutiérrez-Robledo LM, Dartigues JF. Cognitive impairment improves the predictive validity of the phenotype of frailty for adverse health outcomes: the Three-City Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:453–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz NA, Marck MA, Pijl H, Olde Rikkert MG, Bloem BR, Roos RA. Weight loss in neurodegenerative disorders. J Neurol. 2008;255:1872–1880. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandeen-Roche K, Xue QL, Ferrucci L, Walston J, Guralnik JM, Chaves P, Zeger SL, Fried LP. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:262–266. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti E, Bandinelli S, Iorio A, Gangemi S, Camici S, Lauretani F. Relationship between motor behaviour in young/middle age and level of physical activity in late life. Is muscle strength in the causal pathway? In: Capodaglio P, Narici MV, editors. Advances in rehabilitation. Pavia: Maugeri Foundation Books and PI–ME; 2000. pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Wilson RS, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. Physical frailty is associated with incident mild cognitive impairment in community-based older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Wilson RS, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Frailty is associated with incident Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline in the elderly. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:483–489. doi: 10.1097/psy.0b013e318068de1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchman AS, Schneider JA, Leurgans S, Bennett DA. Physical frailty in older persons is associated with Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology. 2008;71:499–504. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000324864.81179.6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari M, Leeuwenburgh C, Lauretani F, Onder G, Bandinelli S, Maraldi C, Guralnik JM, Pahor M, Ferrucci L. Frailty syndrome and skeletal muscle: results from the Invecchiare in Chianti study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1142–1148. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal study: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40:373–383 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA, Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56A:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.M146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L, Wang HX. Brain reserve hypothesis in dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;12:11–22. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Forbes S, Morgan DG, Markle-Reid M, Wood J, Culum I. Physical activity programs for persons with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;3:CD006489. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Williams CS, Richardson ED, Tinetti ME. Impairments in physical performance and cognitive status as predisposing factors for functional dependence among nondisabled older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51A:M283–M288. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51A.6.M283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG, Han L. Transitions between frailty states among community-living older persons. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:418–423. doi: 10.1001/.418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch C, Anderson ML, Newman A, Kop W, Jackson S, Gottdiener J, Tracy R, Fried LP, Cardiovascular Health Study Research Group The association of race with frailty: the cardiovascular health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16:545–553. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WT, Seelaar H, Josephs KA, Knopman DS, Boeve BF, Sorenson EJ, McCluskey L, Elman L, Schelhaas HJ, Parisi JE, Kuesters B, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Petersen RC, Swieten JC, Grossman M. Survival profiles of patients with frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1359–1364. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzitari M, Carlo A, Baldereschi M, Pracucci G, Maggi S, Gandolfo C, Bonaiuto S, Farchi G, Scafato E, Carbonin P, Inzitari D, ILSA Working Group Risk and predictors of motor-performance decline in a normally functioning population-based sample of elderly subjects: the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Akpom CA. A measure of primary sociobiological functions. Int J Health Serv. 1976;6:493–507. doi: 10.2190/UURL-2RYU-WRYD-EY3K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson EB, Shadlen MF, Wang L, McCormick WC, Bowen JD, Teri L, Kukull WA. Survival after initial diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:501–509. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi S, Minicuci N, Harris T, Motta L, Baldereschi M, Carlo A, Inzitari D, Crepaldi G. High plasma insulin and lipids profile in older individuals: the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M236–M242. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.4.M236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcgivney SA, Mulvihill M, Taylor B. Validating the GDS depression screen in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:98–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb04969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of the Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–944. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottenbacher KJ, Ostir GV, Peek MK, Snih SA, Raji MA, Markides KS. Frailty in older Mexican Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1524–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza F, Solfrizzi V, Frisardi V, Maggi S, Sancarlo D, Addante F, D’Onofrio G, Seripa D, Pilotto A (2011) Different models of frailty in predementia and dementia syndrome. J Nutr Health Aging 15: (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pilotto A, Sancarlo D, Panza F, Paris F, D'Onofrio G, Cascavilla L, Addante F, Seripa D, Solfrizzi V, Dallapiccola B, Franceschi M, Ferrucci L. The Multidimensional Prognostic Index (MPI), based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts short- and long-term mortality in hospitalized older patients with dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;18:191–199. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Howlett SE, MacKnight C, Beattie BL, Bergman H, Hébert R, Hogan DB, Wolfson C, McDowell I. Prevalence, attributes, and outcomes of fitness and frailty in community-dwelling older adults: report from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59A:1310–1317. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.12.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Eggimann B, Cuénoud P, Spagnoli J, Junod J. Prevalence of frailty in middle-aged and older community-dwelling Europeans living in 10 countries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:675–681. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute (2004) SAS/STAT user’s guide, version 9.1, Cary, USA

- Solfrizzi V, Panza F, Colacicco AM, D'Introno A, Capurso C, Torres F, Grigoletto F, Maggi S, Parigi A, Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Scafato E, Farchi G, Capurso A, Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging Working Group Vascular risk factors, incidence of MCI, and rates of progression to dementia. Neurology. 2004;63:1882–1891. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144281.38555.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solfrizzi V, Colacicco AM, D'Introno A, Capurso C, Torres F, Rizzo C, Capurso A, Panza F. Dietary intake of unsaturated fatty acids and age-related cognitive decline: a 8.5-year follow-up of the Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:1694–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Balfour JL, Higby HR, Kaplan GA. Antecedents of frailty over three decades in an older cohort. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53B:S9–S16. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53B.1.S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging Working Group Prevalence of chronic diseases in older Italians: comparing self-reported and clinical diagnoses. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26:995–1002. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.5.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CH, Weiss D, Sourial N, Karunananthan S, Quail JM, Wolfson C, Bergman H. Frailty and its association with disability and comorbidity in a community-dwelling sample of seniors in Montreal: a cross-sectional study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2010;22:54–62. doi: 10.1007/BF03324816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods NF, LaCroix AZ, Gray SL, Aragaki A, Cochrane BB, Brunner RL, Masaki K, Murray A, Newman AB, Initiative WH. Frailty: emergence and consequences in women aged 65 and older in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1321–1330. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, 10th revision (ICD-10). Chapter V, categories F00–F99. Mental, behavioural, and developmental disorders, clinical description and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Xie J, Brayne C, Matthews FE, Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study collaborators Survival times in people with dementia: analysis from population based cohort study with 14 year follow-up. BMJ. 2008;336:258–262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39433.616678.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982–1983;17:37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]