Abstract

Two patients with mini-volcano type of skin lesions which showed histopathologic features of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) have been described. It was localised and linear in one case while widespread in the other. Both responded to sodium stibogluconate. The importance of recognising new emerging foci of CL is emphasised.

Keywords: Cutaneous leishmaniasis, leishmania tropica, mini-volcano

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) has been reported in India mainly from the north-western regions. The wide range of clinical manifestations of CL have been well documented from different endemic countries across the world. In the present article, we report two cases with unusual presentation of CL in whom the initial diagnosis of CL was missed either due to a lapse in careful history taking or under-recognition of the newly emerging foci of CL.

Case Reports

Case 1

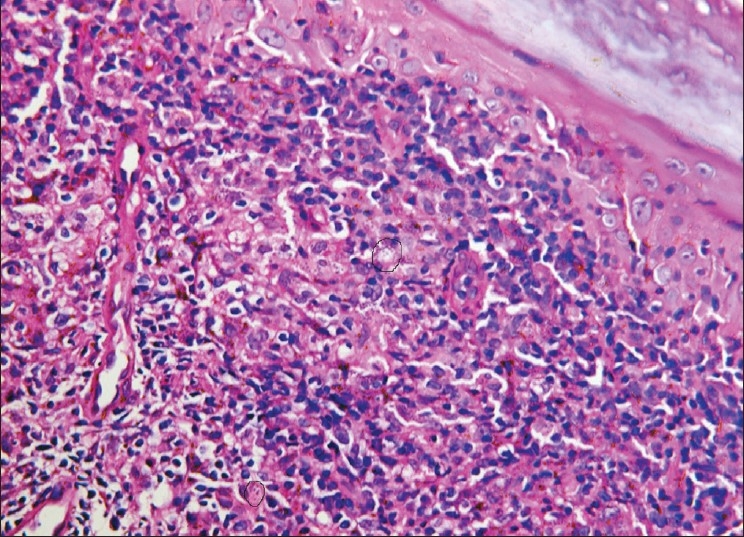

A 49-year-old man presented with asymptomatic eruptions on the hand for the past 8 months. They increased in size and few had ulcerated. There were no systemic complaints and family members were normal. The patient had been making frequent visits to his home town in the sub-Himalayan state of Uttarakhand, the last visit being a month prior to the onset of lesions. Cutaneous examination revealed well-defined erythematous coalescing papules arranged linearly on the radial aspect of the dorsum of his right hand. A solitary lesion was present on the middle of the dorsum of the same hand. Some had developed central ulceration, giving a picture of ulcerated papulonodules [Figure 1]. A provisional diagnosis of sporotrichosis had been considered. Histopathological examination showed numerous 2 to –4 μm round to oval organisms, with the kinetoplast located at the periphery of vacuolated cytoplasm of macrophages consistent with amastigotes [Figure 2]. The polymerase chain reaction was positive for Leishmania tropica. A diagnosis of CL was made. The patient received intralesional sodium stibogluconate 1-2 ml (100 mg/ml) every 2 weeks, with 80% improvement after two injections.

Figure 1.

Coalescing papules, some resembling a mini-volcano; solitary lesion is also seen

Figure 2.

Numerous Leishman-Donovan bodies within and without macrophages

Case 2

A 60-year-old woman presented with asymptomatic, multiple, grouped lesions on the abdomen and left elbow of 1 year duration and an ulcer on the left foot since 2 months. Cutaneous examination revealed multiple, well-defined and grouped erythematous papules on the abdomen and left elbow. The lesions had started as papules, few of which were similar to the mini-volcanoes described in case 1. The others enlarged to form crateriform wells with prominently raised borders and surrounding erythema [Figure 3]. A solitary clean ulcer of size 3 cm × 3 cm with well-defined margins was present over the dorsum left foot at the base of the little toe. Systemic examination and routine investigations (hemogram, kidney function tests and liver function tests) were within normal limits. The clinical possibilities suggested were sarcoidosis and granuloma annulare. The histopathological examination was similar to the previous examination, leading to the diagnosis of CL. Re-interrogation disclosed that she had stayed in Jaisalmer for 9 months, a city in the state of Rajasthan, 5 months prior to the onset of the disease. She was given 1 g (10 ml) of sodium stibogluconate daily by the intravenous route. A week later, the lesions showed signs of regression, after which she was lost to follow-up.

Figure 3.

Abdominal lesions simulating crateriform wells

Discussion

CL is a vector-borne protozoal infection of the skin caused by several species of Leishmania, mainly L. major, L. tropica and L. aethiopica (together known as L. tropica complex) in the old world and species of L. braziliensis and L. mexicana in the new world. New world species do not occur in India.[1] In India, CL is usually caused by L. tropica, and man is the most common reservoir.[2]

In India, indigenous cases of CL are confined to the north western half of the Indo-Gangetic plain, including the dry areas along the Indo-Pakistan border from Amritsar to Gujarat.[1] There are reports of large-scale epidemics of oriental sore in Delhi and the adjoining areas before 1940, and the disease showed transient disappearance with the National Malaria Eradication Program in 1958 during which most of these endemic areas came under DDT spray to which sandflies are highly susceptible.[3] According to a study undertaken in the year 1973 between January and March to assess the status of infection in the endemic belt, it was found that sporadic cases of CL were found restricted to some localised areas predominantly in the state of Rajasthan.[4]

The usual clinicopathological picture of CL varies from erythematous papules to noduloulcerative forms and, mostly, the lesions are seen on the exposed parts of the body. There are worldwide reports of unusual presentations of CL from different endemic countries: acute paronychial forms, fissure leishmaniasis, chancriform, annular, palmo-plantar, zosteriform, erysipeloid, lupoid, scar leishmaniasis, subcutaneous submandibular nodule, whitlow, discoid lupus erythematosus-like, squamous cell carcinoma-like, eczematous, verrucous, mucocutaneous and panniculitic variants.[5–11] The wide variation in the morphological presentation of CL has been attributed to many factors relating to the strain of the parasite, pathogenicity, virulence, infectivity, immunological status of the host and geographical factors of the place of dwelling.[2,7]

Our patients presented with an uncommon morphology. In one, the disease was localised and in the other, it was widespread. In the first patient, the ulcerated papular lesions resembled a smaller counterpart of the volcanic nodules that have been described as a morphological variant of CL, often restricted to the deeper subcutaneous plane. In the other patient, the lesions had progressed deeper and wider, giving rise to crateriform wells. Histopathology in both had revealed numerous leishman-donovan bodies after which the diagnosis of CL was made. They responded to sodium stibogluconate injections. The linearity of the lesions and a history of hailing from a state known to be endemic for sporotrichosis prompted the diagnosis in the first patient.[12] Of late, a new focus of CL has been reported from the areas along the Himalayan belt and adjoining areas of bordering districts situated along the river Satluj.[13] In the second patient too, who was later known to have spent some time living in a part of the country highly endemic for CL, this rare presentation of CL had been missed. The notable feature was the striking similarity between the morphological presentations in both cases, which was localised in one and widespread in the other. Because cosmopolitan cities of India have to deal with a large number of migrants, it is important for us to be aware of new foci of leishmaniasis within the country.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Rastogi V, Nirwan PS. Cutaneous leishmaniasis- an emerging infection in a non-endemic areas and a brief update. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2007;25:272–5. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.34774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hepburn NC. Cutaneous leishmaniasis- an overview. J Post Grad Med. 2003;49:50–4. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma MI, Suri JC, Kalra NL, Krishna Mohan, Swami PN. Epidemiological and entomological features of an outbreak of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Bikaner, Rajasthan, during 1971. J Comm Dis. 1973;5:54–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma MI, Suri JC, Kalra NL. Studies on cutaneous leishmaniasis in India (A note on the current status of CL in North–Western India as determined during 1973) J Comm Dis. 1973;5:73–9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kibbi AG, Paulette GK, Kurban AK. Sporotrichoid leishmaniasis in patients from Saudi Arabia - clinical and histological features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:759–64. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raja KM, Khan AA, Hameed A, Rahman SB. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:111–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bongiorno MR, Pistone G, Arico’ M. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sicily. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:286–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bari A, Bari A, Ejaz A. Fissure leishmaniasis: A new variant of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bari A, Rahman S. Many faces of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:23–7. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.38402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma A, Gulati A, Kaushik R. Cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as a submandibular nodule: A case report. J Cytol. 2007;24:149–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eryilmaz A, Durdu M, Baba M, Bal N, Yigit F. A case with two unusual findings: Cutaneous leishmaniasis presenting as panniculitis and pericarditis after antimony therapy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:295–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.04337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal S, Gopal K, Umesh MD, Kumar B. Sporotrichosis in Uttarakhand (India): A report of nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:367–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma RC, Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Sharma A. A new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Himachal Pradesh. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:170–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]