Sir,

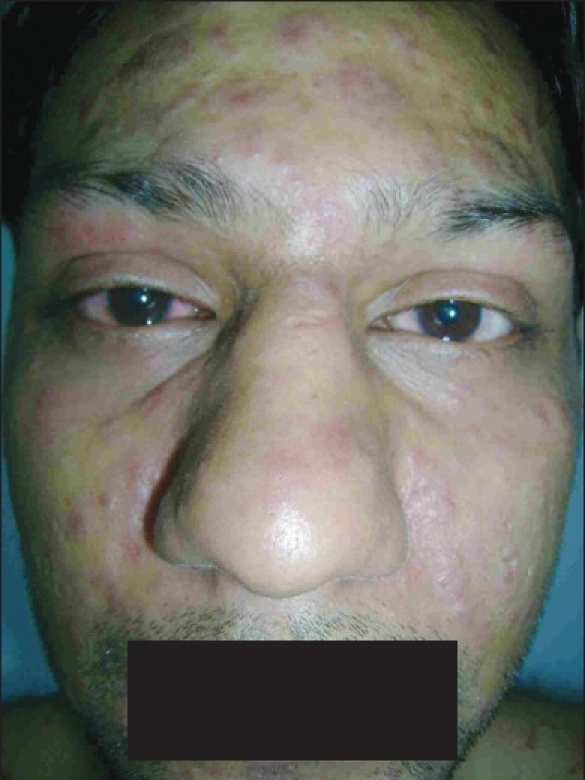

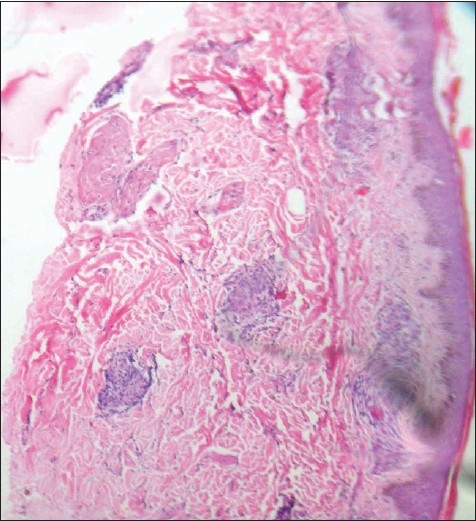

A 28 years old male patient presented with a reddish asymptomatic rash that at first appeared over the forearms, and then spread rapidly all over the body. He was diagnosed as a case of sputum positive pulmonary tuberculosis 9 months back and put on standard four drug antitubercular therapy “isoniazid + rifampicin + pyrazinamide + ethambutol” for 2 months, and then continued on two drug therapy, till he presented with the rash. There was no history of sexual exposure. On examination, widespread erythematous macules, papules, and plaques were distributed bilaterally symmetrically over the face, trunk, upper extremities [Figure 1], and to a lesser extent over the lower extremities with sparing of the palms and soles. Some of the papules and plaques showed scaling on their surface. In addition, multiple hyperpigmented macules and patches were found on the upper limbs. On diascopy, the plaques showed an appearance similar to apple jelly nodules. There was complete absence of pruritus. The rash worsened and was followed by painful red eyes [Figure 2]. The chest X-ray showed clearance of his previous lesions with minimal scar. CT scan of chest, routine blood counts, and blood biochemistry were normal. Serum calcium and serum ACE level were also within normal limits. The Mantoux test was negative. Ultrasound examination of abdomen showed splenomegaly. Ophthalmological examination revealed pan-uveitis. A skin biopsy revealed noncaseating granulomas [Figure 3]. He was diagnosed as a case of sarcoidosis and started on 50 mg/day of prednisolone, which led to dramatic improvement of his eye problem and skin rash within a week.

Figure 1.

Widespread erythematous papules and plaques over trunk and upper extremities

Figure 2.

Facial involvement with uveitis

Figure 3.

Noncaeseating granulomas in dermis (H and E stain, ×100)

The presentation of this patient brought differential diagnosis of sarcoidosis, miliary tuberculosis, papulonecrotic tuberculid, maculopapular drug reaction, and secondary syphilis. The patient developed the lesions while being on anti-TB therapy, so tuberculid and military tuberculosis were ruled out. The absence of pruritus ruled out drug reaction. There was neither any history of exposure, nor generalized lymphadenopathy on examination. The absence of psoriasiform hyperplasia, spongiosis, and plasma cells in the biopsy made the diagnosis of secondary syphilis unlikely. The presence of noncaseating granulomas in skin biopsy, negative Mantoux test, pan-uveitis proved the diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis, with splenomegaly indicating possible abdominal involvement. There was no evidence of pulmonary sarcoidosis though, with normal X-ray, CT scan, and normal serum calcium and ACE level.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disorder characterized pathologically by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in involved tissues. The etiology and pathogenesis of sarcoidosis has been a debatable subject for years. It is generally agreed that this is a tissue reaction to environmental agents (inorganic and organic) in a genetically susceptible individual.[1] Sarcoidosis is remarkably similar to tuberculosis in both clinical and histopathological features and Mycobacterium has also been identified as a possible etiological agent in sarcoidosis. Miliary sarcoidosis following the treatment of miliary tuberculosis has been described.[2] A recent meta-analysis of 31 studies showed that 26.4% of biopsies from sarcoidosis patients were positive for mycobacterial DNA or RNA and there was 9–19-fold increased odds over nonsarcoidosis control tissues.[3] Our case developed skin lesions while still on anti-TB drugs for his sputum positive pulmonary tuberculosis. The present hypothesis of sarcoidosis is that it is a tissue reaction resulting from a host response that is effective in killing but ineffective in antigen removal. In our case the anti-TB drugs cured his pulmonary TB but have somehow changed the host response resulting in systemic sarcoidosis. There are very few reports of concomitant tuberculosis and sarcoidosis.[4,5] So, this is a rare case of systemic sarcoidosis in a patient still on the treatment for sputum positive pulmonary tuberculosis and provides an in interesting clue to the ongoing debate on the etiopathogenesis of sarcoidosis.

References

- 1.Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:365–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hatzakis K, Siafakas NM, Bouros D. Miliary sarcoidosis following miliary tuberculosis. Respiration. 2000;67:219–22. doi: 10.1159/000029492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, Jindal SK. Molecular evidence for the role of mycobacteria in sarcoidosis: A meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:508–16. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oluboyo PO, Awotedu AA, Banach L. Concomitant sarcoidosis in a patient with tuberculosis: First report of association in Africa. Cent Afr J Med. 2005;51:123–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong CF, Yew WW, Wong PC, Lee J. A case of concomitant tuberculosis and sarcoidosis with mycobacterial DNA present in the sarcoid lesion. Chest. 1998;114:626–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]