Abstract

Periodontitis is a destructive inflammatory disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth and is caused by specific microorganisms or a group of specific microorganisms. Association of periodontal infection with organ systems like cardiovascular system, endocrine system, reproductive system, and respiratory system makes periodontal infection a complex multiphase disease. Inflamed periodontal tissues produce significant amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, mainly interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which may have systemic effects on the host. Low birth weight, defined as birth weight less than 2500 g, continues to be a significant public health issue in both developed and developing countries. Research suggests that the bacteria that cause inflammation in the gums can actually get into the bloodstream and target the fetus, potentially leading to premature labor and low birth weight (PLBW) babies. One reasonable mechanism for this is the deleterious effect of endotoxin released from gram-negative bacteria responsible for periodontal disease. Hence, periodontal disease appears to be an independent risk factor for PLBW and there is a need to expand preventive measures for pregnant women in coordination with the gynecological and dental professions.

Keywords: Cytokines, dental, periodontitis, premature labor and low birth weight

INTRODUCTION

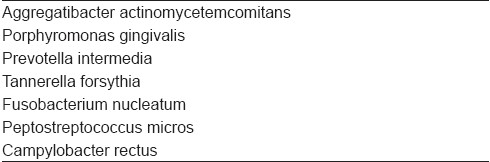

Periodontitis is a destructive inflammatory disease of the supporting tissues of the teeth and is caused by specific microorganisms or a group of specific microorganisms [Table 1], resulting in progressive destruction of periodontal ligament and alveolar bone with periodontal pocket formation, gingival recession or both.[1,2] Periodontal diseases are recognized as infectious processes that require bacterial presence and a host response and are further affected and modified by other local, environmental, and genetic factors. Association of periodontal infection with organ systems like cardiovascular system, endocrine system, reproductive system, and respiratory system makes periodontal infection a complex multiphase disease. Bacteria are the primary etiological agents in periodontal disease, and it is estimated that more than 500 different bacterial species are capable of colonizing the adult mouth.[3] Inflamed periodontal tissues produce significant amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, mainly interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β), IL-6, PGE2, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), which may have systemic effects on the host. Periodontitis initiates systemic inflammation and can be monitored by inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein or fibrinogen levels.

Table 1.

Microorganisms commonly associated with periodontitis

PHARMACOLOGY OF PRO-INFLAMMATORY CYTOKINES ASSOCIATED WITH PERIODONTITIS

Continuous production of cytokines in inflamed periodontal tissues is responsible for the progress of periodontitis and periodontal tissue destruction. Particularly, inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-lα, 1L-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, are present in the diseased periodontal tissues, and their unrestricted production seems to play a role in chronic leukocyte recruitment and tissue destruction. Acute periodontal disease primarily involves a local innate immune response to the microflora of the oral biofilm. Gingival epithelial cells recognize bacterial cell components via toll-like receptors and respond by producing IL-1 and TNF-α. Bacteria and bacterial products also penetrate into the underlying tissues. There they interact with fibroblasts and dendrite cells. These cells also produce proinflammatory cytokines. Additional immune signals are generated by alternative complement activation. These bacterial products and pro-inflammatory cytokines affect vascular endothelial cells as well. Endothelial cells express cellular adhesion molecules, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM and VCAM) that recruit circulating immune cells. Vascular permeability is also increased, allowing the influx of phagocyte cells and serum into the gingival tissue. Neutrophils and macrophages are attracted to the site of infection by chemotaxis following gradients of complement proteins, cytokines, and bacterial products. Activated macrophages produce interleukin-12 (IL-12) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ). Overall, these processes result in gingival inflammation and are responsible for the clinical manifestations of gingivitis, further leading to periodontitis. It is possible that monitoring cytokine production or its profile may allow us to diagnose an individual's periodontal disease status and/or susceptibility to the disease.

LOW BIRTH WEIGHT INFANTS

Low birth weight, defined as birth weight less than 2500 g, continues to be a significant public health issue in both developed and developing countries.[4] Preterm delivery (PTD) is the major cause of neonatal mortality and nearly one-half of all serious long-term neurological morbidities.[5] Premature labor and low birth weight (PLBW) infants are still 40 times more likely to die during the neonatal period. PLBW infants who survive the neonatal period face a higher risk of several neurodevelopmental disturbances, health problems (such as asthma, upper and lower respiratory infections, and ear infections), and congenital anomalies.[4] Some risk factors that have been associated with PLBW include a high (>34 years) and low (<17 years) maternal age, a low socioeconomic status, inadequate prenatal care, drug abuse, alcohol and tobacco use, hypertension, diabetes, and multiple pregnancies. Despite increasing efforts to diminish the effects of these risk factors through preventive interventions during prenatal care, there has been only a small decrease in the number of PLBW infants. There is a reason to believe that other unrecognized risk factors may contribute to the continuing prevalence of PLBW infants. One possible contributing factor to this phenomenon is the effect of an infection on PLBW. It is possible that subclinical genitourinary and periodontal infections can adversely affect the pregnancy outcomes. Women with preterm labor do not invariably present with positive amniotic fluid culture, suggesting that subclinical infections, resulting in translocation of bacteria, bacterial metabolites, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), may account for some of the inflammatory processes associated with PLBW.

PERIODONTAL INFECTION IN PREMATURE LABOR AND LOW BIRTH WEIGHT

The concept that periodontal disease might influence systemic health is not new. Miller originally published his focal infection theory in 1891,[6] suggesting that microorganisms or their waste products gain entrance of parts of the body adjacent to or remote from the mouth. Infection is now considered one of the major causes of PLBW deliveries, responsible for somewhere between 30 and 50% of all cases, and periodontitis and periodontal diseases are true infections of the oral cavity.[1] The oral cavity works as a continuous source of infectious agents and its condition often reflects the progression of systemic pathologies. Periodontal infection happens to serve as a bacterial reservoir that may exacerbate systemic diseases. Research suggests that the bacteria that cause inflammation in the gums can actually get into the bloodstream and target the fetus, potentially leading to PLBW babies. One reasonable mechanism begins with endotoxin resulting from gram-negative bacterial infections (such as periodontal disease). These endotoxins stimulate the production of cytokines and prostaglandins (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α), which in appropriate quantities stimulate labor,[5] and pro-inflammatory mediators may cross the placenta barrier and cause fetal toxicity resulting in PTD and low birth weight babies.[7] High concentrations of these cytokines in pregnant women are responsible for rupture of the uterine membranes leading to premature birth and retardation. As periodontal medicine is still in its infancy here in Asia, there is a compelling need to determine the possible association between adverse pregnancy outcomes and periodontal infections. It has been well documented that periodontal disease is a treatable and preventable condition. In the event of a positive association of periodontal infection with PLBW, this would have potential applications in preventive oral health programs as an integral component of prenatal care for pregnant mothers. Indeed, as healthcare professionals working as a team, an understanding of the role of periodontal–systemic relationship and its implications will further enhance the quality of medical and dental care being provided to our patients in the community.[7] Several animal and clinical studies clearly indicate an association between periodontal infection and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Although no definitive causal relationship has been established and other explanations for the correlation might be offered, a model can nevertheless be envisaged wherein chronic periodontal infection could mediate this systemic effect through one or more of the following mechanisms:[4]

Translocation of periodontal pathogens to the fetoplacental unit;

Action of a periodontal reservoir of LPS on the fetoplacental unit; and

Action of a periodontal reservoir of inflammatory mediators (IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, PGE2) on the fetoplacental unit.

RECOMMENDED ORAL HYGIENE PRACTICES AND VISITS TO DENTIST DURING PREGNANCY

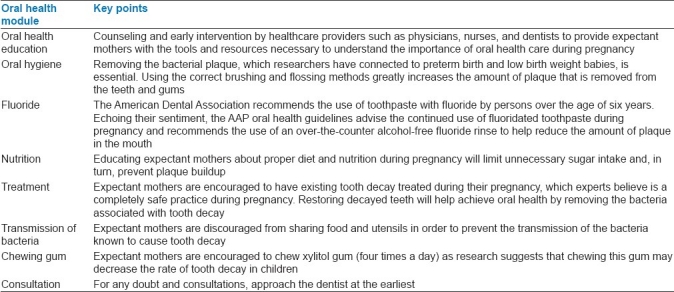

Oral health guidelines for pregnant women assist them in maintaining healthy teeth and gums during their pregnancy and into the early stages of motherhood. The American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAP) announced new oral health guidelines for pregnant women in 2009, which have been modified and given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Oral health guidelines

SUMMARY

Thus, it can be concluded that periodontal disease appears to be an independent risk factor for PLBW and there is a need to expand preventive measures for pregnant women in coordination with the gynecological and dental professions, and to provide professional oral hygiene measurements during pregnancy.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saini R, Marawar PP, Shete S, Saini S. Periodontitis a true infection. J Glob Infect Dis. 2009;1:149–50. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.56251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Aiuto F, Parkar M, Andreou G, Brett PM, Ready D, Tonetti MS. Periodontitis and atherogenesis: Causal association or simple coincidence. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:402–1l. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore WE, Moore LV. The bacteria of periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. 1996;5:66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1994.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGaw T. Periodontal diseases and pre-term delivery of low birth weight infants. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68:165–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffcoat MK, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: Results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:875–80. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller WD. The human mouth as a focus of infection. Dent Cosm. 1891;33:689–713. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeo BK, Lim LP, Paquette DW, Williams RC. Periodontal Disease – The Emergence of a Risk for Systemic Conditions: Pre-term low birth weight. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]