Abstract

Saliva is a complex fluid, which influences oral health through specific and nonspecific physical and chemical properties. The importance of saliva in our everyday activities and the medicinal properties it possesses are often taken for granted. However, when disruptions in the quality or quantity of saliva do occur in an individual, it is likely that he or she will experience detrimental effects on oral and systemic health. Often head and neck radiotherapy has serious and detrimental side effects on the oral cavity including the loss of salivary gland function and a persistent complaint of a dry mouth (xerostomia). Thus, saliva has a myriad of beneficial functions that are essential to our well-being. Although saliva has been extensively investigated as a medium, few laboratories have studied saliva in the context of its role in maintaining oral and general health.

Keywords: Diagnostic fluid, human saliva, saliva, salivary gland

INTRODUCTION

It is probably surprising for most people to learn that saliva has been used in diagnostics for more than 2000 years.[1] Ancient doctors of traditional Chinese medicine have concluded that saliva and blood are “brothers” in the body and they come from the same origin.[2,3] It is believed that changes in saliva are indicative of the wellness of the patient.[4] The thickness and smell of saliva, as well as patients’ gustatory sensation of their own saliva are all used as symptoms of a certain disease state of the body.[5,6]

Analyses of the properties of saliva using biochemical and physiological methodologies can be traced back to at least over a century ago.[6–8] It is obvious that in 1898, when Chittenden and Mendel[9] conducted their study on the influence of alcoholic drinks upon digestion and secretion, the measurement of total organic constituents, salts, and chlorine in saliva was already being performed routinely.[7,9] In the late 19th century, researchers had already learnt that saliva had digestive powers,[10–12] mainly in the form of amylolysis[13,14] and proteolysis.[15,16] Studies in the early 20th century had shown some evidence of the dietary effect of saliva.[1,12] Highly sensitive and high-throughput assays such as mass spectrometry,[17,18] RT-PCR,[19,20] microarray,[21,22] and nano-scale sensors[23] that can measure proteins[24,25] and nucleic acids[21,26] with minimal sample requirement in a short period of time allowed scientists to broaden the utility of saliva.

BIOLOGY OF SALIVA

Saliva is produced and secreted from salivary glands. The basic secretary units of salivary glands are clusters of cells called acini.[2] These cells secrete a fluid that contains water, electrolytes,[27–30] mucus,[7,31] and enzymes,[14,32,33] all of which flow out of the acinus into collecting ducts. Within the ducts, the composition of the secretion is altered.[34] Much of the sodium is actively reabsorbed,[35,36] potassium is secreted,[36–38] and large quantities of bicarbonate ion[39] are secreted. Small collecting ducts within salivary glands lead into larger ducts, eventually forming a single large duct that empties into the oral cavity.[34]

Few important functions of saliva

Saliva serves many roles,[2] some of which are important to all species and others to only a few:

Lubrication and binding: The mucus in saliva[40] is extremely effective in binding masticated food into a slippery bolus that (usually) slides easily through the esophagus[41] without inflicting damage to the mucosa.[10,40,42,43]

Solubilization of dry food: In order to be tasted, the molecules in food must be solubilized.[44,45]

Oral hygiene: The oral cavity is almost constantly flushed with saliva, which floats away food debris and keeps the mouth relatively clean.[46,47] The flow of saliva diminishes considerably during sleep,[29,30,42] allow populations of bacteria to build up in the mouth – the result is dragon breath in the morning.[47,48] Saliva also contains lysozyme, an enzyme that lyses many bacteria and prevents the overgrowth of oral microbial populations.[46–50]

Initiation of starch digestion: In most species, the serous and acinar cells secrete an alpha amylase which can begin to digest dietary starch into maltose.[12,44,45]

INCREDIBLE INSIGHTS INTO HEALTH AND DISEASE ARE OFFERED THROUGH ANALYSIS OF SALIVA

Scientists concur that the diagnosis and prevention of diseases using human saliva[42,51,52] is about to be explored as more and more laboratories and medical practitioners get ready for this new technology.[53,54] Unlike blood testing, saliva analysis looks at the cellular level (the biologically active compounds) and therefore saliva is truly a representative of what is clinically relevant.[52,55] Blood analysis, on the other hand, looks at compounds as they travel through the blood serum, most of which are protein bound. Researchers experienced in saliva analysis are able to predict, diagnose, or prevent many health problems and diseases.[8,56,57]

Molecules freely travel through the cells and into saliva ducts and it is these small molecules that can be assayed in saliva.[58] Hormones are smaller molecules and can be tested in saliva[59,60] and they are indicators of health and diseased status in humans.[58,59,60] A saliva test can make information available that may be obscured when looking for information in the blood.[42]

A factor of significance when assaying saliva is that molecules at the cellular level are found at very low levels; hence results are reported in pico- to nanograms.[23,61] Only a small number of medical testing labs have so far developed the technology to assay such a lower concentration of biologically active molecules like proteins,[25,51,62] RNA,[21,63] and DNA.[64] The technology however is improving all the time. The new technology development is extremely sensitive and easily measures the low levels of biologically active molecules found in saliva.[55]

Just a few of the many health issues and diseases that can be diagnosed through saliva and helped, resolved, or prevented through supplementation include but not limited to the[56] following: acne,[58] cholesterol,[61] male pattern baldness,[61] cancer,[65,66] stress,[67] heart problems,[68] heart palpitations,[68] allergies,[8] cold body temperature,[1] sleep problems,[1] inability to absorb calcium,[38,69] and difficulties in conceiving.[70,71] In fact it is hormone supplementation[59,60] that has become the centerpiece of those growing number of doctors who have joined the emerging science of antiaging medicine.[18]

WHAT'S NEXT? SALIVA TESTING OFFERS A POTENTIAL SUBSTITUTE TO BLOOD TESTING

Proteomics

Researchers have identified the largest number of proteins to date in human saliva,[25,72] a preliminary finding that could pave the way for more diagnostic tests based on saliva samples.[56] Such tests show promise as a faster, cheaper, and potentially safer diagnostic method than blood sampling.[51,73] There is a growing interest in saliva as a diagnostic fluid,[56] due to its relatively simple and minimally invasive collection.[74] The same proteins present in blood are also present in saliva from fluid leakage at the gum line. It is considerably easier, safer, and more economical to collect saliva than to draw blood, especially in children and elderly patients.[61,75] While saliva tests won’t replace blood tests for all diagnostic applications, but in the future they could prove to be a potentially life-saving alternative to detect diseases where early diagnosis is critical, such as certain cancers.[54,65,66,76,77]

Diagnostic assays using saliva are a relatively new but growing technology.[54] Several tests are in the pipeline for uses ranging from pregnancy testing[71,78,79] to the detection of chemicals such as alcohol[9] and other drugs.[8,18,80] One of the hurdles in developing new tests is a lack of understanding of the human proteome,[54] or the study of large sets of proteins,[25,62,72] particularly those that can serve as biomarkers[81,82] for the presence of disease.[1,65,66,83]

Most proteome studies have focused on specific tissues and human blood samples, but a few studies represent the salivary proteome. Not much is known yet about the salivary proteome, but more should be known in the near future.[53,70,73,84] Using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis in combination with mass spectrometry,[17] other researchers were able to identify up to 28 proteins in saliva, including 19 proteins only found in saliva and 9 proteins also present in blood serum.[72,85–87]

Using a single saliva sample from a healthy, nonsmoking male subject,[88] the researchers were able to identify 102 proteins, including 35 salivary proteins and 67 common serum proteins.[62,72,85,89] Identifying all of the serum proteins present in saliva could take many more years. With advances in instrumentation, it is predicted that the number of serum proteins identified in saliva will increase significantly, although it will probably never match the number of serum proteins found in blood,[90] mainly because serum proteins[72] are only a tiny part of saliva, described as a dilute, watery solution containing electrolytes, minerals, buffers, and proteins.[27,28,29,30,72] Blood tests are a well-established, proven methodology, and it may take some time before saliva tests can become as reliable as serum tests. In the future, patient and doctors can look forward to more saliva-based tests.[1,3,6]

Genomics

Saliva and other oral fluids support a host of functions in the oral cavity.[44] These fluids reduce biomass and provide mechanical cleansing of teeth,[42,91] provide an optimal pH in which oral functions are efficiently carried out, and contain an array of antimicrobial components.[34,47,48] Saliva is not merely an ultrafiltrate of plasma; it contains the entire library of proteins, hormones, antibodies, and other molecular compounds which are typically measured in routine blood tests.[1,10,25,43,47,59,60] Thus, saliva functions as a diagnostic window to the body, both in health and in disease. Oral samples include saliva, as well as buccal swabs, and mucosal transudates.[6,34,42,92,93] Saliva, as a diagnostic medium, is easy to collect and poses none of the risks, fears, or invasiveness of drawing blood. Salivary diagnostic tests could eliminate the need not only for a trained technician but also of the potential risk of contracting infectious disease for both a technician and the patient.[6,53,54]

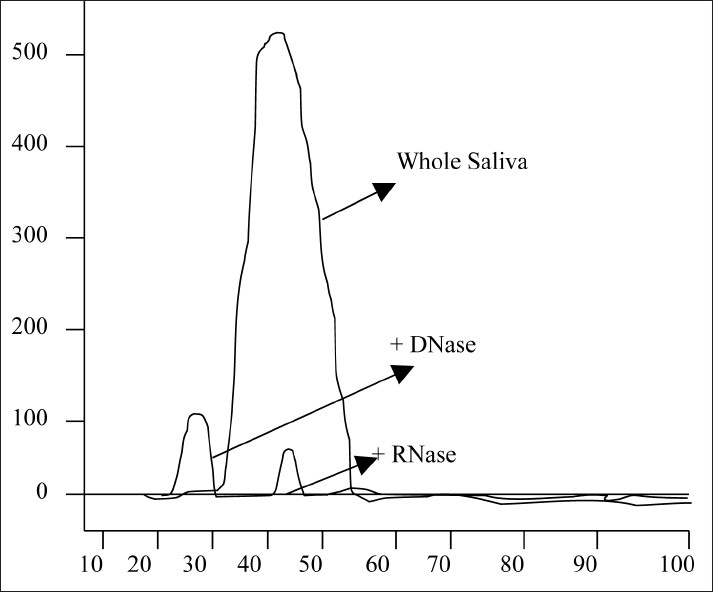

Scientists have long recognized saliva as a mirror of the state of the body's health. Until recently, the problem with developing the field of salivary diagnostics was that specific and informative biomarkers exist in saliva in relatively low quantities.[65,81,82] However, the development of new, exquisitely sensitive amplification techniques such as RT-PCR,[90] Q-PCR,[90,94] and high-density oligonucleotide microarrays[17,18] has demonstrated the feasibility of using saliva as a diagnostic probe[53] for the rapid and unambiguous detection of oral biomarkers.[81] Interestingly, saliva acts as a wide resource for genomic information useful for studying the potential disease status by analyzing their RNA level [Figure 1].[65,73,77,95]

Figure 1.

The RNA profile in whole saliva

Interestingly, a cadre of scientific groups is advancing the development of micro- and nanotechnology-based biosensors[23] to detect salivary biomarkers.[81,82] Current efforts also focus on cataloging the human salivary proteome. Future efforts will determine differences in salivary biomarkers from healthy controls compared with those in patients with a variety of diseases and disorders.[52,53,81,96]

Testing for HIV positivity[75,97,98] is one example of a powerful use of saliva in the diagnosis of infectious diseases. Early efforts indicate that there exist differences in patterns of mRNA expression in saliva that would indicate the presence of a developing oral squamous cell carcinoma.[76,84,99,100]

Salivary mRNA may serve as a chemical signature that a particular gene has been expressed. There is also evidence that saliva may be useful for monitoring the presence of biomarkers indicating the presence of neoplasia in remote sites, for instance, breast cancer.[96,101,102] Salivary diagnostic tests may provide an avenue to allow for the detection of malignancies at a sufficiently early stage that treatment is likely to be successful, and to provide inexpensive testing which will reduce affordability and accessibility barriers to early diagnosis.[53,66,84,99,101]

CONCLUSION

Each of us may have inside our mouths a key to the pathological and disease biomarker library hidden inside our bodies. Saliva – the source of all this information – is the secretory product of glands located in or around the oral cavity. If we could read the stories of diagnostic information present within saliva, then the abundance of information waiting to be found could be comparable to a vast vault of information such as the internet. The relationship between salivation and behaviors within our daily lives is undeniable. Yet most people never appreciate the uniqueness of saliva. Throughout the world, saliva carries definite positive and negative connotations with it based upon its social, psychological, behavioral, and cultural settings. The thought of saliva may be viewed as grotesque in one population, yet conversely it may be the vehicle of blessing in other cultures. Saliva's double nature brings up some interesting cultural, social, behavioral, and psychological points about how saliva is perceived in the world, some of which are stated below in order to present saliva as the spirited fluid it is.

Efforts on the discovery of analytes in the saliva of normal and diseased subjects suggest an additional function of saliva, a local and systematic diagnostic tool. Analytes used for disease detection range from proteins, to antibodies, and nucleic acids that are of either human microorganism origins. Highly sensitive and high-throughput assays such as mass spectrometry, RT-PCR, microarray, and nano-scale sensors that can measure proteins and nucleic acids with a minimal amount of sample requirement in a short period of time allowed scientists to broaden the utility of saliva as a diagnostic tool.

As research evidence accumulates, saliva-based diagnostics are being widely accepted by clinicians and patients. Research efforts are underway to reveal the connection of salivary changes in all aspects to systemic health status. The noninvasive nature and ease of collection have made saliva the fluid of choice for not only diagnostic but also the more important health surveillance purposes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greabu M, Battino M, Mohora M, Totan A, Didilescu A, Spinu T, et al. Saliva-a diagnostic window to the body, both in health and in disease. J Med Life. 2009;2:124–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miletich I. Introduction to salivary glands: Structure, function and embryonic development. Front Oral Biol. 2010;14:1–20. doi: 10.1159/000313703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bibby BG. What about the saliva? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1949;2:72–81. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(49)90129-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iorgulescu G. Saliva between normal and pathological. Important factors in determining systemic and oral health. J Med Life. 2009;2:303–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cove-Smith R, Moncrieff A. Defective Saliva. Proc R Soc Med. 1935;29:126–7. doi: 10.1177/003591573502900221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farnaud SJ, Kosti O, Getting SJ, Renshaw D. Saliva: Physiology and diagnostic potential in health and disease. Scientific World Journal. 2010;10:434–56. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miglani DC, Raghupathy E. Research on saliva. A-critique. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1968;40:131–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kefalides PT. Saliva research leads to new diagnostic tools and therapeutic options. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:991–2. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-12-199912210-00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chittenden RH, Mendel LB. A Further Study of the Influence of Alcohol and Alcoholic Drinks upon Digestion, with Special Reference to Secretion. Am J Physiol. 1898;1:164–209. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dechaume M, Goguel S, Poullain P. Human saliva: Physical properties; chemical composition; cytology; bacteriology; serological properties; role. Revue Stomatol. 1950;51:521–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neilson CH, Lewis DH. The effect of diet on the amylolytic power of saliva. J Biol Chem. 1908;4:501–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neilson CH, Terry OP. “The adaptation of the salivary secretion to diet.”. Am J Physiol. 1906;15:406–11. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobsen N, Hensten-Pettersen A. Salivary amylase I- An assay method of alpha-amylase. Caries Res. 1970;4:193–9. doi: 10.1159/000259641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meites S, Rogols S. Amylase isoenzymes. CRC Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1971;2:103–38. doi: 10.3109/10408367109151305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riekkinen PJ, Ekfors TO. Demonstration of a proteolytic enzyme, salivain, in rat saliva. Acta Chem Scand. 1966;20:2013–8. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.20-2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pawilowska-Michalik H, Halawa B, Potoczek S. Proteolytic activity of saliva. Pol Med J. 1969;8:694–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun X, Salih E, Oppenheim FG, Helmerhorst EJ. Activity-based mass spectrometric characterization of proteases and inhibitors in human saliva. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2009;3:810–20. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huestis MA. A new ultraperformance-tandem mass spectrometry oral fluid assay for 29 illicit drugs and medications. Clin Chem. 2009;55:2079–81. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.134551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song Q, Lange T, Spahr A, Adler G, Bode G. Characteristic distribution pattern of Helicobacter pylori in dental plaque and saliva detected with nested PCR. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:349–53. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-4-349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hochmeister MN, Rudin O, Ambach E. PCR analysis from cigarette butts, postage stamps, envelope sealing flaps, and other saliva-stained material. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;98:27–32. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-443-7:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Zhou X. RNA profiling of cell-free saliva using microarray technology. J Dent Res. 2004;83:199–203. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schena MD, Shalon Quantitative monitoring of gene expression patterns with a complementary DNA microarray. Science. 1995;270:467–70. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palanisamy V, Sharma S, Deshpande A, Zhou H, Gimzewski J, Wong DT. Nanostructural and transcriptomic analyses of human saliva derived exosomes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Araki Y. Nitrogenous substances in saliva. I. Protein and non-protein nitrogens. Jpn J Physiol. 1951;2:69–78. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Nieuw Amerongen A, Bolscher JG, Veerman EC. Salivary proteins: Protective and diagnostic value in cariology? Caries Res. 2004;38:247–53. doi: 10.1159/000077762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitsouras K, Faulhaber EA. Saliva as an alternative source of high yield canine genomic DNA for genotyping studies. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:219. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wotman S, Mandel ID, Thompson RH, Jr, Laragh JH. Salivary electrolytes, urea nitrogen, uric acid and salt taste thresholds in hypertension. J Oral Ther Pharmacol. 1967;3:239–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venables PH. Electrolytes and behaviour in man. Ciba Found Study Group. 1970;35:113–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawes C. The effects of flow rate and duration of stimulation on the condentrations of protein and the main electrolytes in human parotid saliva. Arch Oral Biol. 1969;14:277–94. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(69)90231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawes C. The effects of flow rate and duration of stimulation on the concentrations of protein and the main electrolytes in human submandibular saliva. Arch Oral Biol. 1974;19:887–95. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(74)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe G. The pathology and physiology of saliva from the standpoint of the acid-base equilibrium. Igaku. 1948;3:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pigman W, Reid AJ. The organic compounds and enzymes of human saliva. J Am Dent Assoc. 1952;45:326–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raus FJ, Tarbet WJ, Miklos FL. Salivary enzymes and calculus formation. J Periodontal Res. 1968;3:232–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1968.tb01925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schneyer LH, Schneyer CA. Secretion of Saliva. Adv Oral Biol. 1964;1:1–31. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4832-3117-4.50007-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tekenbroek JN, Woldring MG. Sodium and potassium content of saliva. Tijdschr Voor Tandheelkd. 1952;59:442–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niedermeier W, Dreizen S, Stone RE, Spies TD. Sodium and potassium concentrations in the saliva of normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1956;9:426–31. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(56)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgen AS. The secretion of potassium in saliva. J Physiol. 1956;132:20–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swanson M, Cacace L. “Saliva calcium and potassium concentrations in the detection of digitalis toxicity.”. Circulation. 1973;47:736–43. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.47.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leung SW. A demonstration of the importance of bicarbonate as a salivary buffer. J Dent Res. 1951;30:403–14. doi: 10.1177/00220345510300031601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simmons NS. Studies on the defense mechanisms of the mucous membranes with particular reference to the oral cavity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1952;5:513–26. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(52)90231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kongara KR, Soffer EE. Saliva and esophageal protection. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1446–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.1124_b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dodds MW, Johnson DA, Yeh CK. Health benefits of saliva: A review. J Dent. 2005;33:223–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Slomiany BL, Murty VL, Piotrowski J, Slomiany A. Salivary mucins in oral mucosal defense. Gen Pharmacol. 1996;27:761–71. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humphrey SP, Williamson RT. A review of saliva: Normal composition, flow, and function. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;85:162–9. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2001.113778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hara AT, Zero DT. The caries environment: Saliva, pellicle, diet, and hard tissue ultrastructure. Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:455–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dewar MR. The saliva: A short review, with special reference to dental caries. Med J Aust. 1950;1:803–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1950.tb80759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tenovuo J. Antimicrobial function of human saliva-how important is it for oral health? Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56:250–6. doi: 10.1080/000163598428400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Kesteren M, Bibby BG, Berry GP. Studies on the Antibacterial Factors of Human Saliva. J Bacteriol. 1942;43:573–83. doi: 10.1128/jb.43.5.573-583.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Belding PH, Belding LJ. Salivary inhibition and dental caries. J Dent Res. 1948;27:480–5. doi: 10.1177/00220345480270040501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferguson DB. Dehydrogenase enzymes in human saliva. Arch Oral Biol. 1968;13:583–8. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(68)90119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lucas GH. The Saliva Test. Can J Comp Med. 1939;3:67–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee YH, Wong DT. Saliva: An emerging biofluid for early detection of diseases. Am J Dent. 2009;22:241–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dawes C. “Considerations in the development of diagnostic tests on saliva.”. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:265–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yeh CK, Christodoulides NJ, Floriano PN, Miller CS, Ebersole JL, Weigum SE, et al. Current development of saliva/ oral fluid-based diagnostics. Tex Dent J. 2010;127:651–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Choi M. Saliva diagnostics integrate dentistry into general and preventive health care. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ferguson DB. “Current diagnostic uses of saliva.”. J Dent Res. 1987;66:420–4. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kunsman K. Oral fluid testing arrives. (34).Occup Health Saf. 2000;69:28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leimola-Virtanen R, Helenius H, Laine M. Hormone replacement therapy and some salivary antimicrobial factors in post- and perimenopausal women. Maturitas. 1997;27:145–51. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(97)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vining RF, McGinley RA. Hormones in saliva. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1986;23:95–146. doi: 10.3109/10408368609165797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Korotko GF, Gotovtseva LP. Pituitary, adrenal and sex hormones in saliva. Fiziol Cheloveka. 2002;28:137–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lusa Cadore E, Lhullier FL, Arias Brentano M, Marczwski Da Silva E, Bueno Ambrosini M, Spinelli R, et al. Salivary hormonal responses to resistance exercise in trained and untrained middle-aged men. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2009;49:301–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wolf RO, Taylor LL. A Comparative Study of Saliva Protein Analysis. Arch Oral Biol. 1964;9:135–40. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(64)90003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu CJ, Kao SY, Tu HF, Tsai MM, Chang KW, Lin SC. Increase of microRNA miR-31 level in plasma could be a potential marker of oral cancer. Oral Dis. 2010;16:360–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bahlo M, Stankovich J, Danoy P, Hickey PF, Taylor BV, Browning SR, et al. Saliva-derived DNA performs well in large-scale, high-density single-nucleotide polymorphism microarray studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:794–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu JY, Yi C, Chung HR, Wang DJ, Chang WC, Lee SY, et al. Potential biomarkers in saliva for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:226–31. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagler RM. Saliva as a tool for oral cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:1006–10. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nicolson N, Storms C, Ponds R, Sulon J. Salivary cortisol levels and stress reactivity in human aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:M68–75. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.2.m68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vinoy S, Mascai-Taylor C. The Relationship Between Areca Nut Usage and Heart Rate in Lactating Bangladeshis. Ann Hum Biol. 2002;29:488–94. doi: 10.1080/03014460110112051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Horton K, Marrack J, Price I. The relation of calcium in the saliva to dental caries. Biochem J. 1929;23:1075–8. doi: 10.1042/bj0231075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cassiday L. Salivary proteome changes as women age. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:4886. doi: 10.1021/pr9009029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salvolini E, Di Giorgio R, Curatola A, Mazzanti L, Fratto G. Biochemical modifications of human whole saliva induced by pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:656–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Masson PL, Carbonara AO, Heremans JF. Studies on the proteins of human saliva. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1965;107:485–500. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(65)90192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mandel ID. “Salivary diagnosis: Promises, promises.”. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;694:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb18336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salisbury E. Method of Obtaining Saliva for Saliva Test. Can J Comp Med. 1939;3:101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sherman GG, Lilian RR, Coovadia AH. Oral fluid tests for screening of human immunodeficiency virus-exposed infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:169–72. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181b9a19c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sato J, Goto J, Murata T, Kitamori S, Yamazaki Y, Satoh A, et al. Changes in saliva interleukin-6 levels in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110:330–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang L, Farrell JJ, Zhou H, Elashoff D, Akin D, Park NH, et al. Salivary transcriptomic biomarkers for detection of resectable pancreatic cancer. (e1-7).Gastroenterology. 2010;138:949–57. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McGregor JA, Hastings C, Roberts T, Barrett J. Diurnal variation in saliva estriol level during pregnancy: A pilot study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:S223–5. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bowsher J. Oral care during pregnancy. Prof Care Mother Child. 1997;7:101–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Borzelleca JF, Doyle CH. Excretion of drugs in saliva. Salicylate, barbiturate, sulfanilamide. J Oral Ther Pharmacol. 1966;3:104–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bast RC, Jr, Lilja H. Translational crossroads for biomarkers. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:6103–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Oliveira VN, Bessa A, Lamounier RP, de Santana MG, de Mello MT, Espindola FS. Changes in the salivary biomarkers induced by an effort test. Int J Sports Med. 2010;31:377–81. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tamarin A. Contemporary Salivary Gland Reserach. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:833–40. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li Y, St John MA, Zhou X, Kim Y, Sinha U, Jordan RC, et al. Salivary transcriptome diagnostics for oral cancer detection. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8442–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Middleton JD. Human Salivary Proteins and Artificial Calculus Formation in vitro. Arch Oral Biol. 1965;10:227–35. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(65)90024-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yan W, Apweiler R, Balgley BM, Boontheung P, Bundy JL, Cargile BJ, et al. Systematic comparison of the human saliva and plasma proteomes. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2009;3:116–34. doi: 10.1002/prca.200800140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chicharro JL, Serrano V, Ureña R, Gutierrez AM, Carvajal A, Fernández-Hernando P, et al. Trace elements and electrolytes in human resting mixed saliva after exercise. Br J Sports Med. 1999;33:204–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.33.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Maliszewski TF, Bass DE. “True and apparent thiocyanate in body fluids of smokers and nonsmokers.”. J Appl Physiol. 1955;8:289–91. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1955.8.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kirc ER, Kesel RG, et al. Amino acids in human saliva. J Dent Res. 1947;26:297–301. doi: 10.1177/00220345470260040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Power DA, Cordiner SJ, Kieser JA, Tompkins GR, Horswell J. PCR-based detection of salivary bacteria as a marker of expirated blood. Sci Justice. 2010;50:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.scijus.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dewar MR. Importance of saliva for the condition of the teeth. Med Welt. 1951;20:842–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Walls HJ. Role of the forensic science laboratory. Br Med J. 1967;2:95–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5544.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hedman J, Nordgaard A, Rasmusson B, Ansell R, Rådström P. Improved forensic DNA analysis through the use of alternative DNA polymerases and statistical modeling of DNA profiles. Biotechniques. 2009;47:951–8. doi: 10.2144/000113246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Akiyama T, Miyamoto H, Fukuda K, Sano N, Katagiri N, Shobuike T, et al. Development of a novel PCR method to comprehensively analyze salivary bacterial flora and its application to patients with odontogenic infections. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;109:669–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de Jong EP, Xie H, Onsongo G, Stone MD, Chen XB, Kooren JA, et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals myosin and actin as promising saliva biomarkers for distinguishing pre-malignant and malignant oral lesions. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11148. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Radpour R, Barekati Z, Kohler C, Holzgreve W, Zhong XY. New trends in molecular biomarker discovery for breast cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:565–71. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2009.0060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Malamud D. Oral diagnostic testing for detecting human immunodeficiency virus-1 antibodies: A technology whose time has come. Am J Med. 1997;102:9–14. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(97)00032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kamat HA, Adhia M, Koppikar GV, Parekh BK. Detection of antibodies to HIV in saliva. Natl Med J India. 1999;12:159–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scully C, Epstein JB. Oral health care for the cancer patient. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1996;32B:281–92. doi: 10.1016/0964-1955(96)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Langevin SM, Stone RA, Bunker CH, Grandis JR, Sobol RW, Taioli E. MicroRNA-137 promoter methylation in oral rinses from patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is associated with gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:864–70. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Streckfus C, Bigler L. The use of soluble, salivary c-erbB-2 for the detection and post-operative follow-up of breast cancer in women: The results of a five-year translational research study. Adv Dent Res. 2005;18:17–24. doi: 10.1177/154407370501800105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Agha-Hosseini F, Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Rahimi A, Seilanian-Toosi M. Correlation of serum and salivary CA125 levels in patients with breast cancer. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2009;10:E001–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]