Abstract

Neurons of the avian cochlear nucleus magnocellularis (NM) receive glutamatergic inputs from the spiral ganglion cells via the auditory nerve and feedback GABAergic inputs primarily from the superior olivary nucleus. We investigated regulation of Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons with ratiometric Ca2+ imaging in chicken brain slices. Application of exogenous glutamate or GABA increased the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in NM neurons. Interestingly, GABA-induced Ca2+ responses persisted into neuronal maturation, in both standard and energy substrate enriched artificial cerebrospinal fluid. More importantly, we found that electrical stimulation applied to the glutamatergic and GABAergic afferent fibers innervating the NM was able to elicit transient [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons, and the amplitude of the Ca2+ responses increased with increasing frequency and duration of the electrical stimulation. Antagonists for ionotropic glutamate receptors significantly blocked these [Ca2+]i increases, whereas blocking GABAA receptors did not affect the Ca2+ responses, suggesting that synaptically released glutamate but not GABA induced the Ca2+ signaling in vitro. Furthermore, activation of GABAA receptors with exogenous agonists inhibited synaptic activity-induced [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons, suggesting a role of GABAA receptors in the regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in the avian cochlear nucleus neurons.

Keywords: auditory, Ca2+ imaging, glutamate receptor, GABA receptor, neuromodulation

Introduction

Calcium (Ca2+) acts as an intracellular messenger that regulates many cellular processes, such as cell growth, differentiation, synaptic transmission, and signaling transduction (Berridge et al., 2003). Homeostasis of Ca2+ dynamics is not only critical for these normal cellular functions, but also imperative for cell survival and maintenance. An excess increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) via certain routes can induce cell death through a number of processes, such as activation of proteases, lipases, and nucleases or an increase in the production of nitric oxide and free radicals (Szydlowska and Tymianski, 2010).

The chicken cochlear nucleus magnocellularis (NM) is an excellent model for studying regulation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling (Rubel and Fritzsch, 2002). Neurons in the NM have three unusual neuronal properties associated with Ca2+ dynamics. First, the NM receives highly active excitatory glutamatergic inputs. These inputs originate purely from the spiral ganglion neurons, and each NM neuron receives only 1–3 large endbulb synapses. These synapses are highly active in neurotransmission, exhibiting a spontaneous firing rate of about 80 Hz in NM neurons and an even higher rate when sounds are present (Warchol and Dallos, 1990; Born et al., 1991). Such a high spiking activity would lead to massive Ca2+ entry into NM neurons, presumably via Ca2+-permeable AMPA and NMDA receptors (Parks, 2000) and subsequently voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) (Lu and Rubel, 2005). Second, the inhibitory inputs to NM neurons, which originate primarily from the ipsilateral superior olivary nucleus (SON) (Lachica et al., 1994; Burger et al., 2005a), are unusually depolarizing and could be excitatory (Lu and Trussell, 2001; Monsivais and Rubel, 2001). Although the maximal membrane depolarization induced by activation of the GABAergic system is only approximately 15 mV and the excitatory action can be efficiently prevented by metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR)- and GABABR-mediated modulation (Lu et al., 2005; Lu, 2007), it is conceivable that activation of the GABAergic pathway can cause Ca2+ entry through low-threshold VGCCs present in NM neurons (Lu and Rubel, 2005). Indeed, application of exogenous GABA does cause [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons, but the receptors mediating the response remain unclear (Lachica et al., 1998). Finally, activation of mGluRs and GABABRs can also contribute to Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons by stimulating the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores and modulating other Ca2+ pathways (Lachica et al., 1998; Zirpel et al., 2000).

To date, studies of intracellular Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons have focused on the [Ca2+]i increases in response to exogenous agonists for glutamate or GABA receptors (Lachica et al., 1995, 1998; Kato and Rubel, 1999; Zirpel et al., 2000; Diaz et al., 2009). This approach has the advantage of using drugs with known concentrations and known specificity. However, because Ca2+ signaling in neurons is highly diverse in its spatial and temporal patterns (Berridge et al., 2003), the Ca2+ responses elicited with bath application of drugs may not faithfully reflect the responses observed under physiological conditions. In contrast, synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ signaling may be more closely associated with physiological responses. Indeed, distinct patterns of [Ca2+]i increases in response to differential patterns of synaptic activity have been reported (Markram and Sakmann, 1994; Lips and Keller, 1999; Ene et al., 2003). Therefore, it is imperative to examine whether and how synaptically released neurotransmitters result in [Ca2+]i increases in neurons as well as whether and how the Ca2+ signaling is regulated. The goal of this study was to elicit [Ca2+]i increases in response to synaptic stimulation in NM neurons, and make comparisons to those in response to bath application of agonists. In addition, we aimed to examine which ionotropic receptors for each neurotransmitter mediate the responses, and how the GABAergic system modulate synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons.

Materials and methods

Slice preparation

Fertilized chicken eggs (Gallus domesticus) were purchased from Moyer’s Chick (Quakertown, PA) and incubated using an RX2 Auto Turner (Lyon Electric Co., Chula Vista, CA). Brainstem slices (300 μm in thickness) were prepared from late-stage embryos (E17-E21) and hatchlings (age up to post-hatch 29 days) as previously described (Tang et al., 2009, 2011), with modification of the artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) components used for dissection and cutting of the brain tissue. The modified ACSF, which is a glycerol-based solution (Ye et al., 2006), contained (in mM) 250 glycerol, 3 KCl, 1.2 KH2PO4, 20 NaHCO3, 3 HEPES, 1.2 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2 and 10 dextrose, pH 7.4, when gassed with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. The procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Northeast Ohio Medical University and are in accordance with National Institute of Health (NIH) policies on animal use. All efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering.

Fura-2 loading and Ca2+ imaging

Fura-2 loading was adapted and slightly modified from previous studies that studied Ca2+ signaling using the same kind of chicken brain slice preparations (Lachica et al., 1995, 1998; Zirpel et al., 1995, 1998, 2000). Slices were incubated at 35 °C for at least 1 hr in normal ACSF containing (in mM) 130 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 3 KCl, 3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4 and 10 dextrose, followed by incubation in ACSF containing Fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2AM, 10 μM), pluronic acid (0.0025%), and sulfinpyrazone (250 μM) for 40 min at room temperature (20–22 °C). For imaging experiments, one brain slice was transferred to a 0.5 ml chamber mounted on an upright Olympus BX60 or BX51 microscope (Japan). The chamber was continuously superfused with ACSF (3–4 mL/min) driven by gravity. The microscope was positioned on the top center of an Isolator CleanTop II and housed in a Type II Faraday cage (Technical Manufacturing Corporation, Peabody, MA). The imaging system (Till Photonics, Germany) consisted of a Polychrome 5000 with its control unit ICU as the illumination source and an IMAGO CCD camera. The brain slice was alternately illuminated with 340 nm and 380 nm excitation wavelengths, and emission was collected at 510 nm using proper filters from Chroma Technology (Rockingham, VT). The interval between image acquisitions was 0.5 s when performing electrical stimulation experiments and 3 or 5 s when bath-applying agonists for glutamate or GABA receptors. Fluorescent image intensities (after background subtraction) were expressed as a ratio of F340/F380, where F340 and F380 represent the averaged fluorescence intensity of the emission light elicited by 340 nm and 380 nm excitation wavelengths, respectively (Chen et al., 2005). The fluorescence intensity of the postsynaptic cells was measured from an area of the cytoplasm excluding the nucleus, if possible, and the presynaptic endbulb terminals (Fig. 1). The experiments were run using Tillvision Imaging System v4.5 (Till Photonics, Germany) and were carried out at room temperature (20–22 °C).

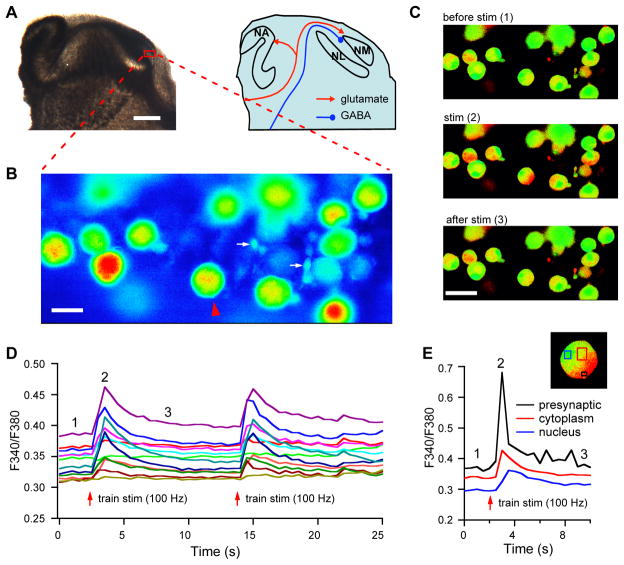

Figure 1.

Fura-2 labeling and ratiometric Ca2+ imaging in nucleus magnocellularis (NM) neurons. A: Photograph (bright field illumination) of a chicken brainstem slice (without any staining) and a schematic drawing illustrating the auditory brainstem nuclei and the afferent pathways to the NM. NA: nucleus angularis; NL: nucleus laminaris. B: Fura-2-labeled NM neurons were readily identified as large and round bushy cells (soma diameter of about 15–20 μm) when excited with light at the wavelength of 340 nm. Glial cells (indicated by the arrows) are distinguishably much smaller in size. C: Ratio images (F340/F380) before, during, and after electrical shocks (train stimulation at 100 Hz, duration of 200 ms) to the afferent fibers of the NM. In response to the train stimulation, the fluorescence intensity at 340 nm increased while that at 380 nm decreased. Therefore the ratio images (F340/F380) showed hotter color in responding cells. D: The electrical shocks (indicated by the red arrow) induced transient [Ca2+]i increases in 10 out of 12 cells. When the same stimulation was repeated, the responses were similar to those to the first stimulation. E: Ratios of F340/F380 obtained from areas indicated in the inset plotted against time, showing a strong Ca2+ response in the presynaptic endbulb, a moderate response in the postsynaptic cytoplasm and a delayed response in the nucleus. Scale bar = 500, 15, and 30 μm in A, B, and C, respectively.

Extracellular synaptic stimulation was performed using bipolar tungsten electrodes or concentric bipolar electrodes with a tip core diameter of 127 μm (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Square electric pulses (duration of 0.2 ms) were delivered through a Stimulator A320RC (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) controlled by a Train/Delay Generator DG2A (Digitimer Ltd., England). The stimulation electrode was placed using a Micromanipulator U-3C or NMN-25 (Narishige, Japan). In the majority of experiments, the stimulating electrode was placed lateral to the NM, where the auditory nerve fibers and the SON fibers innervating the NM travel together (Young and Rubel, 1983; Lachica et al., 1994).

The drugs were delivered via bath application. Glutamate (100 μM) and GABA (100 or 500 μM) were used to activate glutamate receptors and GABA receptors, respectively. D-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV, 50–100 μM) and 1-naphthylacetyl spermine trihydrochloride (NAS, 30 μM) were used to block NMDA receptors and AMPA receptors, respectively. SR95531 (10–20 μM) was used to block GABAA receptors. Muscimol (10 μM) and baclofen (100 μM) were used to activate GABAA receptors and GABAB receptors, respectively. To activate mGluRs, 100 μM of tACPD was used. All chemicals and drugs were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), except for Fura-2AM and tACPD, which were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and Tocris (Ballwin, MO), respectively.

Data analysis

The peak value of the ratio of F340 over F380 relative to the baseline was measured and the percent change in response to drug application calculated. Graphs were constructed in Igor (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Statistical differences were detected using t-test or ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, and P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant. Means and standard errors of the means are reported (n in parenthesis indicates the number of cells and N the number of slices).

Whole-cell recordings

Voltage clamp whole-cell recordings are the same as described previously (Tang et al., 2011). Briefly, after incubation brain slices were transferred to a 0.5 mL chamber mounted on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 FS Plus microscope (Zeiss, Germany) with a 40X- water-immersion objective and infrared, differential interference contrast optics. The chamber was continuously superfused with ACSF (1–2 mL/min) by gravity. Patch pipettes were drawn on an Electrode Puller PP-830 (Narishige, Japan) to 1–2 μm tip diameter. The electrodes had resistances between 3 and 7 M when filled with a solution containing (in mM): 105 K-gluconate, 35 KCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 4 ATP-Mg, and 0.3 GTP-Na, with pH of 7.2 (adjusted with KOH) and osmolarity between 280 and 290 mOsm/L. The Cl− concentration (37 mM) in the internal solution approximated the physiological Cl− concentration in NM neurons (Lu and Trussell, 2001; Monsivais and Rubel, 2001). Voltage clamp experiments were performed with an AxoPatch 200B (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) at a holding potential of −70 mV. Extracellular stimulation was performed as described above for Ca2+ imaging experiments. Recording protocols were written and run using the acquisition and analysis software AxoGraph X (AxoGraph Scientific, Sydney, Australia).

RESULTS

The boundary of the NM in acute brain slices can be readily identified under bright field microscopy (Lu, 2009). Neurons in the NM at the ages we studied are known to be homogeneous in their morphology and physiology, with a gradient distribution of their neuronal properties along the tonotopic axis (Fukui and Ohmori, 2004). They are homologous to the bushy cells in the mammalian cochlear nuclei, with large and round cell bodies and none or few short dendrites. Therefore, Fura-2-labeled NM neurons were readily identified when excited with light at the wavelength of 340 nm, and easily distinguished from glial cells, which were much smaller (Fig. 1A, B).

The main goal of this study was to characterize synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons. Pilot studies showed that electrical shocks (train stimulation at 100 Hz, duration of 200 ms) to the afferent fibers of the NM induced transient [Ca2+]i increases in 10 out of 12 cells, reported as the ratio (in arbitrary units) of the fluorescence intensity at 340 nm to that at 380 nm (Fig. 1C, D). When the same stimulation was repeated, the responses were similar to those to the first stimulation (Fig. 1D). Two cells did not show detectable responses. This may be simply because either their afferent fibers were severed during slice preparation or the stimulating electrode did not contact their fibers. For the cells that did respond, two of them were out of focus. Therefore a total of 4 cells in this case would be excluded in analyses of drug effects. The Ca2+ signaling is expected to be different in different cellular compartments, therefore analyses were performed to monitor Ca2+ responses in different cellular domains. Each NM neuron receives only a few (1–3) large excitatory terminals (Endbulb of Held synapses) impinging onto their cell bodies, covering about 60% of the soma area (Parks, 1981). Therefore, Ca2+ increases inside the presynaptic terminals could be detected. In a sampled neuron, the response in the presumably presynaptic endbulb was the strongest, and the response peak in the nucleus area was delayed (Fig. 1E), suggesting dependency of synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ signaling on both time and space domains. The responses in the endbulbs however were not always reliably observed, likely due to variations in location of the endbulbs relative to the cell bodies as well as their small size. Furthermore, the cold spots in the ratio images may indicate the nuclei that were loaded with Fura-2. Excluding the measurement from the presynaptic terminals and the nuclei may help enhance the report of the Ca2+ signaling inside the cytoplasm, although such exclusion could not be done perfectly. The following experiments examined the Ca2+ signaling in the postsynaptic cytoplasm excluding the nuclei and the endbulbs whenever possible. Four series experiments were performed. First, we examined the [Ca2+]i increases in response to application of exogenous glutamate and GABA. Second, we demonstrated that synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons was stimulation frequency- and duration-dependent. Third, we dissected out the contributions of different transmitter receptors using pharmacological tools. Finally, we examined GABA-mediated modulation of synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons.

[Ca2+]i increases in response to exogenous agonists for glutamate or GABA receptors

In normal ACSF that contained 3 mM Ca2+, glutamate (100 μM) or GABA (100 μM) induced [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons (Fig. 2A, B). These cytoplasmic Ca2+ responses could be mediated by two general pathways. One is via extracellular Ca2+ influx through ion channels such as Ca2+-permeable ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) and subsequently VGCCs, and the other is via Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. To block the first pathway, we did the same experiments using Ca2+-free ACSF in which the extracellular Ca2+ was omitted and replaced by the same concentration of Mg2+. In Ca2+-free ACSF, glutamate (100 μM) resulted in [Ca2+]i increases that were smaller in amplitude than the responses recorded in normal ACSF (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, GABA (100 μM) did not produce noticeable Ca2+ responses in Ca2+-free ACSF (Fig. 2D).

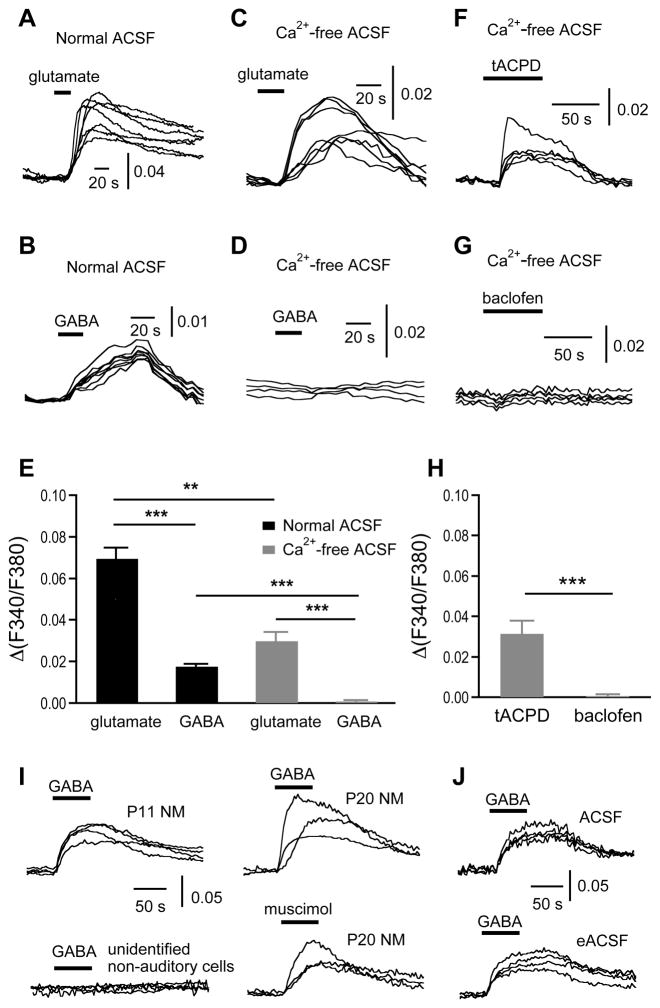

Figure 2.

Bath application of exogenous glutamate induces [Ca2+]i increases in both normal and Ca2+-free ACSF, whereas bath application of exogenous GABA induces Ca2+ responses in normal ACSF only. Notably, GABA-induced Ca2+ responses persist into maturation, even in the presence of energy-enriched ACSF (eACSF), which eliminated or reversed the depolarizing GABA responses in some mammalian systems (Rheims et al., 2009; Holmgren et al., 2010). A–B: Superimposed individual traces showing that glutamate (100 μM) or GABA (100 μM) in normal ACSF induced [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons. The vertical scale bar represents the relative change in the ratio of F340/F380, Δ(F340/F380). C–D: In Ca2+-free ACSF, glutamate (100 μM) induced [Ca2+]i increases, whereas GABA (100 μM) did not. E: Pooled data show that glutamate- and GABA-induced [Ca2+]i increases in normal ACSF (glutamate: n = 115 cells, N = 19 slices; and GABA: n = 34 cells, N = 8 slices). In Ca2+-free ACSF, glutamate (100 μM, n = 20 cells, N = 4 slices) but not GABA (100 μM, n = 14 cells, N = 4 slices) induced [Ca2+]i increases. F–H: In Ca2+-free ACSF, tACPD (100 μM), a broad-spectrum agonist for mGluRs, induced [Ca2+]i increases (0.031 ± 0.007, n = 28 cells, N = 7 slices), whereas baclofen (100 μM), a specific agonist for GABABRs, did not (0.001 ± 0.001, n = 25 cells, N = 7 slices). I: GABA (500 μM) induced [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons obtained from more mature animals (age up to 29 days after hatch) (n = 40 cells, N = 19 slices). The same GABA application did not elicit any noticeable [Ca2+]i increases in unidentified non-auditory cells in the same slice preparations. J: GABA (500 μM) induced similar [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons in the standard ACSF (10 mM glucose as the sole energy source) and in the eACSF (5 mM pyruvate and 4 mM BHB were added to the standard ACSF). All traces are single cell responses from the same slice except for the traces in panels A and C, which are from two slices. In this and subsequent figures, the superimposed individual traces were aligned at the response onset and the baseline was artificially offset for clarity of display. Bars represent means ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 (t test for this figure and ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test for the subsequent figures).

Summary data (Fig. 2E) showed that, at the same and presumably saturating concentration (100 μM), glutamate gave rise to significantly larger [Ca2+]i increases than GABA did in both normal ACSF and Ca2+-free ACSF. The amplitudes of the glutamate- and GABA-induced [Ca2+]i increases in normal ACSF were 0.069 ± 0.006 (n = 115 cells, N = 19 slices) and 0.017 ± 0.001 (n = 34 cells, N = 8 slices), respectively (t-test, P < 0.001). The amplitude of [Ca2+]i increases in Ca2+–free ACSF was smaller than that in normal ACSF (0.030 ± 0.005, n = 20 cells, N = 4 slices, t-test, P < 0.01, compared to normal ACSF; and 0.001 ± 0.001, n = 14 cells, N = 4 slices, t-test, P < 0.001, compared to normal ACSF, for glutamate and GABA, respectively), indicating that pathways other than ion channels on the cellular membrane may be involved, e.g., Ca2+ release from internal stores through mGluR-activated signaling pathways (Zirpel et al., 1995; Lachica et al., 1998; Kato and Rubel, 1999), or Ca2+ signaling induced by other neurotransmitters such as ATP (Milenkovic et al., 2009). Indeed, in Ca2+-free ACSF, tACPD (100 μM), a broad-spectrum agonist for mGluRs, induced [Ca2+]i increases (n = 28 cells, N = 7 slices), whereas baclofen (100 μM), a specific agonist for GABABRs, did not (n = 25 cells, N = 7 slices) (Fig. 2F-H, t-test, P < 0.001). These results essentially agree with previous studies (Lachica et al., 1995, 1998; Kato and Rubel, 1999; Zirpel et al., 2000; Diaz et al., 2009) (with minor discrepancies, see Discussion) and indicate that under these conditions, Ca2+ influx from extracellular space is the major pathway for cytoplasmic Ca2+ responses in NM neurons.

The GABA-induced Ca2+ responses in NM neurons are interesting and worth further investigation. Physiological studies using chicks age up to 10 days after hatch showed that the GABAergic transmission in NM neurons maintains a depolarizing feature in relatively mature animals (Lu and Trussell, 2001), whereas GABAergic transmission in non-auditory neurons in the same slice preparations has already switched to be a conventional hyperpolarizing inhibition (Monsivais and Rubel, 2001). To confirm and to extend the findings of these physiological studies, we repeated the experiments of bath application of agonists for GABA receptors in brain slices obtained from more mature animals (8 hatchlings ages P3–P29). We reliably elicited Ca2+ responses by applying GABA (100 or 500 μM) or a specific GABAA receptor agonist muscimol (100 μM), whereas the same drug application did not elicit any noticeable Ca2+ increases in unidentified non-auditory neurons in the same brain slices (Fig. 2I) (GABA for NM: n = 40 cells, N = 19 slices; Muscimol for NM: n = 10 cells, N = 5 slices; GABA for unidentified cells: n = 5 cells, N = 3 slices). These results provided evidence that the depolarizing effects of GABA in NM neurons persisted into maturation. To confirm that GABA-induced Ca2+ responses were not due to the use of the standard ACSF that contained glucose as the sole energy source, which may be responsible for generating depolarizing GABA responses caused by insufficient energy sources (Rheims et al., 2009; Holmgren et al., 2010), we examined the GABA effects in the presence of an energy substrate enriched ACSF (eACSF), which contained 5 mM pyruvate and 4 mM 3-β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) as additional energy substrates besides glucose. We observed similar GABA-induced Ca2+ responses as those recorded in the standard ACSF (Fig. 2J, n = 18 cells, N = 3 slices), indicating that the GABA-induced Ca2+ responses were not artifacts caused by insufficient energy sources in the standard ACSF.

[Ca2+]i increases in response to electrical stimulation of the afferent fibers innervating the NM

To elicit synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ responses, we applied electrical stimulation to the area lateral to the NM, where the auditory nerve fibers and the SON fibers innervating NM neurons travel together (Fig. 3A). By doing so, we aimed to elicit [Ca2+]i increases in response to receptor activation by endogenous neurotransmitters, namely, synaptically released glutamate and/or GABA. To test the effectiveness of the stimulus, we performed whole-cell voltage clamp recordings from NM neurons in response to single-pulse electrical stimulation. Under control conditions, the stimulus elicited postsynaptic currents (PSC) of two components, representing a fast EPSC and a slow IPSC (Lu, 2007). Blocking ionotropic glutamate receptors with DNQX (50 μM) and APV (50 μM) eliminated the EPSC, and adding an antagonist for GABAA receptors (SR95531, 20 μM) nearly completely blocked the PSC. In another cell, SR95531 eliminated the IPSC, and adding DNQX and APV blocked the PSC completely (Fig. 3B). The stimulus elicited both EPSC and IPSC in 9 out of 11 NM neurons, and two cells showed EPSC only (Fig. 3C), indicating that the stimulus is effective in activating both the glutamate and the GABA pathways, with a few exceptions. The parameters of the stimulus pulse (1 mA in intensity, and 0.2 ms of single pulse duration) were chosen for studying Ca2+ responses based on these physiological results and previous studies using similar preparations (Lu, 2007, 2009).

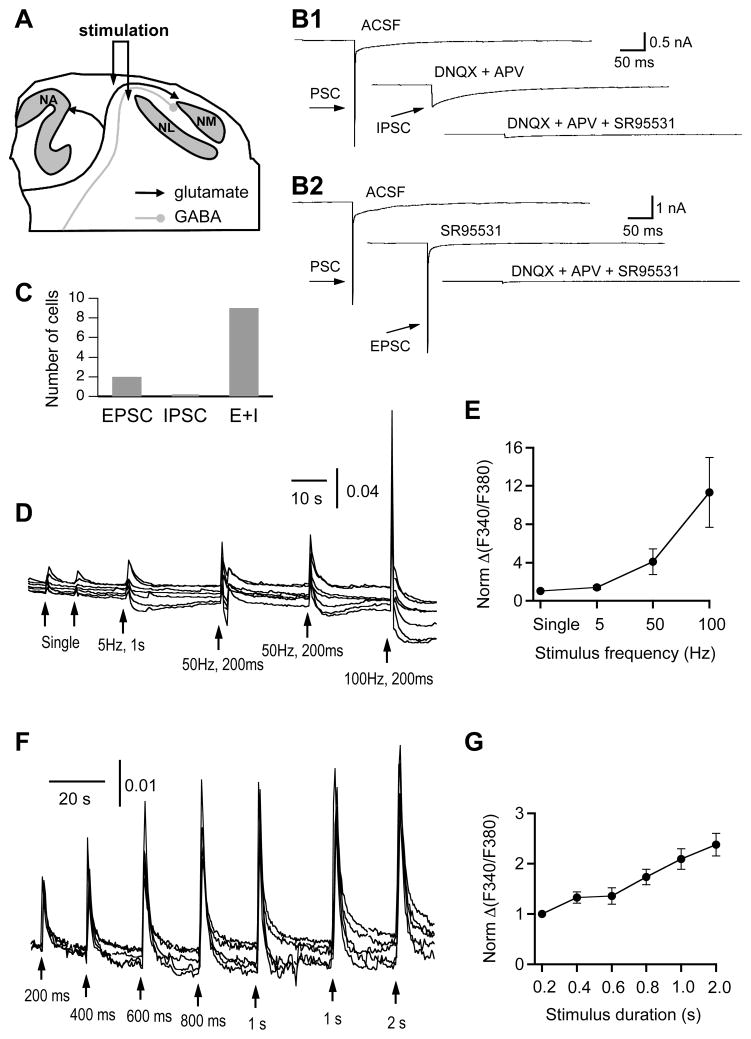

Figure 3.

Stimulus frequency- and duration-dependent [Ca2+]i increases in response to synaptic stimulation. A: Schematic drawing showing that the stimulating electrode is positioned lateral to the NM where the auditory nerve and SON fibers innervating the NM travel together. B: Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings from two NM neurons in response to single-pulse electrical stimulation. The stimulus artifacts are blanked for clarity. In ACSF, both cells responded with a fast followed by a slow postsynaptic current (PSC). Blocking ionotropic glutamate receptors (50 μM DNQX and 50 μM APV for AMPA and NMDA receptors, respectively) eliminated the fast component, leaving the IPSC intact, and adding an antagonist for GABAA receptors (SR95531, 20 μM) nearly completely blocked the PSC (B1). In another cell, SR95531 was applied first, which eliminated the slow component, leaving the EPSC intact, and adding DNQX and APV blocked the PSC completely (B2). C: Out of 11 NM neurons stimulated with the protocol, nine cells showed both EPSC and IPSC (E+I), and two cells EPSC only. D: Transient [Ca2+]i increases were induced by electrical stimulations of a single pulse, 5 pulses of 5 Hz (total duration of 1 s), 10 pulses of 50 Hz (total duration of 200 ms), and 20 pulses of 100 Hz (total duration of 200 ms), respectively. The single-pulse stimulation and the train stimulation at 50 Hz were repeated twice, and similar responses were observed to the same stimulation. The amplitude of each stimulus pulse was 1 mA and duration was 0.2 ms. E: Quantification of the amplitudes of the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i responses, normalized to the averaged peak value induced by single-pulse stimulation. The normalized amplitudes at the frequency of 5, 50, and 100 Hz were 1.4 ± 0.2, 4.1 ± 1.4 and 11.3 ± 3.6, respectively (n = 11–15 cells, N = 2 slices). F: Transient [Ca2+]i increases were induced by electrical stimulations at the same frequency (100 Hz) but different durations (from 200 ms to 2 s). The stimulation at the duration of 1 s was repeated twice, which elicited similar responses. G: Quantification of the amplitudes of the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i responses, normalized to the averaged peak value induced by the stimulation of the shortest duration (200 ms). The amplitudes at the duration of 400, 600, 800, 1,000, and 2,000 ms were 1.3 ± 0.1, 1.4 ± 0.1, 1.7 ± 0.1, 2.1 ± 0.2 and 2.4 ± 0.3, respectively (n = 24 cells, N = 7 slices). The traces in D are single cell responses from the same slice, and the traces in F are single cell responses from two slices. For whole-cell recordings, NM neurons were held at −70 mV, and the solution in the recording electrodes contained high Cl− (37 mM) approximating the physiological concentration.

Once NM neurons that responded with [Ca2+]i increases to synaptic stimulations were identified, we studied the relationships between the [Ca2+]i increases in postsynaptic NM neurons and the stimulation by changing either the frequency of the stimulus or the total duration of the stimulation at a fixed frequency. We observed stimulus frequency- and duration-dependent [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons (Fig. 3D–G). The amplitude of the Ca2+ responses increased with increasing stimulation frequencies, which ranged from single pulse to higher stimulation frequencies at 5 Hz (5 pulses), 50 Hz (10 pulses), and 100 Hz (20 pulses). When normalized to the peak amplitude of the Ca2+ responses elicited with single stimulation pulse, the peak amplitude of the [Ca2+]i increases elicited at 100 Hz showed an 11.3-fold increase (Fig. 3D, E). When the stimulus frequency was fixed at 100 Hz and the total duration of the stimulation was increased, the amplitude of Ca2+ responses increased gradually and modestly, with a 2.4-fold increase when the duration was increased by 10-fold (Fig. 3F, G). Because they produced relatively reliable and large, but not saturating, [Ca2+]i increases, the stimulation parameters (amplitude of 1 mA, single-pulse duration of 0.2 ms, frequency of 100 Hz, and total stimulation duration of 200 ms) were used as a standard paradigm in the following experiments.

Synaptic activity-induced [Ca2+]i increases were primarily mediated by iGluRs

Because the synaptic stimulation applied to the lateral part of the NM activates both the glutamatergic and the GABAergic pathways (Monsivais et al., 2000; Lu, 2007), the potential sources primarily responsible for the [Ca2+]i increases could be as follows: 1) Ca2+-permeable iGluRs (AMPA and NMDA receptors); 2) VGCCs activated by membrane depolarization due to the glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission; and/or 3) Ca2+ release from internal stores triggered by G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) signaling transduction pathways. We mainly focused on Ca2+ responses triggered by ionotropic receptors for the following reasons. First, ionotropic receptors mediate fast signal transmission and thus fast Ca2+ signaling with distinct temporal and spatial patterns, which may be physiologically more important than overall [Ca2+]i increases with slower kinetics. Second, although contributions by VGCCs to synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ signaling are important, they cannot be studied pharmacologically because blocking VGCCs will disable synaptic transmission.

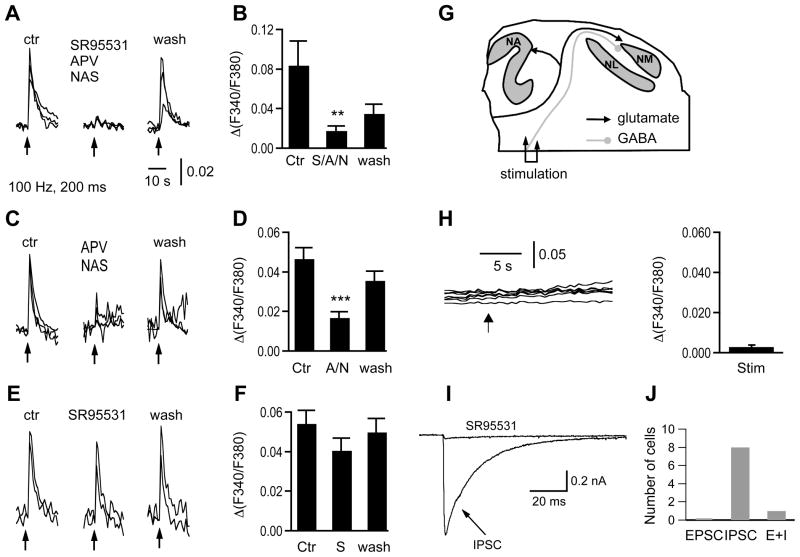

We determined the contributions of different ionotropic glutamate or GABA receptors using pharmacological agents. To block GABAA, NMDA, and AMPA receptors, SR95531 (10 μM), APV (100 μM), and NAS (30 μM) were used, respectively. Application of a cocktail containing SR95531, APV, and NAS significantly blocked the synaptic activity-induced [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons. The amplitudes of the [Ca2+]i increases were 0.084 ± 0.025, 0.018 ± 0.005, and 0.034 ± 0.010 for control, cocktail (S/A/N), and washout, respectively (n = 12 cells, N = 4 slices; ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4A, B). Omitting SR95531 in the cocktail resulted in similar blockade of the Ca2+ responses (Fig. 4C, D). The amplitudes of the [Ca2+]i increases were 0.047 ± 0.006, 0.017 ± 0.003, and 0.035 ± 0.005 (n = 16 cells, N = 7 slices) for control, the cocktail without SR95531 (A/N), and washout, respectively (ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P < 0.001). Application of DNQX (50 μM) and APV (100 μM) resulted in similar inhibition, with the [Ca2+]i increases being 0.024 ± 0.005, 0.002 ± 0.001, and 0.017 ± 0.002 (p < 0.001, n = 21 cells, N = 4 slices) for control, DNQX and APV, and washout, respectively. However, application of DNQX and APV also caused the baseline Ca2+ responses to shift to smaller amplitude, possibly because of the light color of the ACSF introduced by DNQX. This baseline shift might affect the peak value of the Ca2+ responses to synaptic stimulation. Therefore, we chose to report the data by using NAS in Figure 4. It is well known that NAS blocks Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors (e.g. Yin et al., 2002), and more importantly, AMPA receptors of NM neurons are Ca2+-permeable due to the low expression level of the channel subunit GluR2 (Parks, 2000). On average, SR95531 (10 μM) alone did not significantly affect the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases. The amplitudes of the [Ca2+]i increases were 0.054 ± 0.007, 0.040 ± 0.007, and 0.050 ± 0.007 (n = 20 cells, N = 8 slices) for control, SR95531, and washout, respectively (Fig. 4E, F; ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P > 0.05). Consistent with this observation, electrical shocks (train stimulations, 10–100 Hz, duration of 200–1000 ms) applied to the area of the slices (ventral to the auditory fiber pathway) that presumably contained GABAergic but not the glutamatergic fibers innervating the NM did not elicit any noticeable [Ca2+]i increases (Fig. 4G, H, n = 60 cells, N = 9 slices). Such stimulations did elicit inhibitory postsynaptic currents (IPSC) in NM neurons. Electrical stimulation of the presumably GABAergic pathway originating from the SON elicited IPSC only in 8 out of 9 NM neurons, with the other cell responding with EPSC as well (Fig. 4I, J). These results indicate that the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons are mainly triggered by iGluRs, with possible minor contributions by metabotropic receptors and GABAARs. It is worth noting that while iGluRs in NM neurons allowed Ca2+ entry upon activation, they also depolarized the membrane and activated VGCCs. Therefore the Ca2+ entry via iGluRs is direct or primary, whereas the Ca2+ entry via VGCCs is indirect or secondary.

Figure 4.

Synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases are mediated primarily by iGluRs. The synaptic stimulation (100 Hz, 20 pulses, duration of 200 ms) is indicated by the upward arrow. A: Bath application of a cocktail containing GABAA receptor blocker SR95531 (10 μM), NMDA receptor blocker APV (100 μM), and AMPA receptor blocker NAS (30 μM) nearly completely blocked synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases in the sample cells. The responses partially recovered after washout of the blockers. B: Pooled data show that the cocktail significantly reduced the amplitude of the synaptic stimulation-induced Ca2+ responses (n = 12 cells, N = 4 slices). C, D: Omitting SR95531 in the cocktail resulted in similar effects as the cocktail did, reducing the responses significantly (ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P < 0.001). E, F: SR95531 alone did not significantly affect the averaged stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases (n = 20 cells, N = 8 slices; ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P > 0.05). The traces in each panel are single cell responses from the same slice. G: Schematic drawing showing the position of the electrical stimulation of the presumably GABAergic pathway originating from the SON. H: Train stimulation (100 Hz, 50 pulses, indicated by the arrow) did not elicit [Ca2+]i increases in any of the 7 NM neurons recorded from one slice. Pooled data showed that there were not detectable Ca2+ responses to such stimulations (n = 60 cells, N = 9 slices). I: Representative IPSC recorded in one NM neuron in response to single-pulse stimulation was abolished by SR95531 (20 μM). J: The electrical stimulus elicited IPSC only in 8 out of 9 NM neurons, with the other cell responding with EPSC as well. Recording conditions were the same as in Figure 3B.

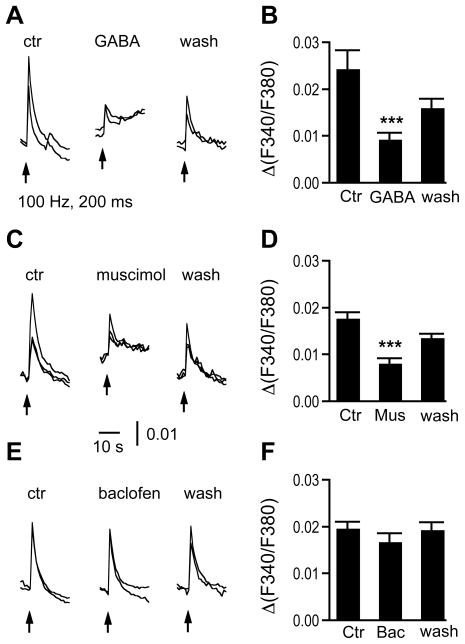

GABA modulation of synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases in the NM

Previous electrophysiological studies have shown that GABA modulates neurotransmission and the excitability of NM neurons through its metabotropic and ionotropic receptors, respectively. Via activation of presynaptic GABABRs, GABA regulates glutamate release (Otis and Trussell, 1996; Brenowitz et al., 1998; Brenowitz and Trussell, 2001) as well as GABA release in NM neurons (Lu et al., 2005). Via activation of postsynaptic GABAARs, GABA produces potent shunt inhibition and improves temporal coding in the same neurons (Monsivais et al., 2000; Monsivais and Rubel, 2001). Both actions could lead to reduced [Ca2+]i increases mediated by iGluRs and/or VGCCs. To test this hypothesis, we studied the effects of agonists for GABA receptors on synaptic stimulation-induced Ca2+ responses (presumably equivalent to synaptic glutamate induced responses) in NM neurons.

Bath application of GABA (100 μM) resulted in a slow [Ca2+]i increase, consistent with the observation presented in Figure 2. GABA application reversibly inhibited synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases. The amplitudes of the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases were 0.024 ± 0.004, 0.009 ± 0.002 and 0.016 ± 0.002 for control, GABA, and washout, respectively (n = 13 cells, N = 4 slices; ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P < 0.001) (Fig. 5A, B). Muscimol (10 μM), a GABAAR agonist, induced a similar slow [Ca2+]i increase as GABA did, and also reversibly inhibited the synaptic stimulation-induced Ca2+ responses. The slow [Ca2+]i increase was blocked by Ni2+ (100 μM), a low-threshold VGCC blocker (n = 9 cells, N = 3 slices). The amplitudes of the [Ca2+]i increases were 0.018 ± 0.001, 0.008 ± 0.001, and 0.014 ± 0.001 (n = 29 cells, N = 6 slices) for control, muscimol, and washout, respectively (Fig. 5C, D; ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P < 0.001). Baclofen (100 μM), a GABABR agonist, on average did not affect the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases. The amplitudes of the [Ca2+]i increases were 0.020 ± 0.002, 0.017 ± 0.002, and 0.019 ± 0.002 (n = 15 cells, N = 4 slices) for control, baclofen, and washout, respectively (Fig. 5E, F; ANOVA post hoc Fisher’s test, P > 0.05).

Figure 5.

Activation of GABAA receptors reversibly inhibits synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases. A: Bath application of GABA (100 μM) induced a slow [Ca2+]i increase (indicated by the artificially upwardly shifted baseline), which is consistent with the observation in Figure 2B. The application also inhibited synaptic stimulation-induced Ca2+ responses. B: Pooled data show that GABA significantly reduced the amplitude of the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases (n = 13 cells, N = 4 slices). C, D: Muscimol (10 μM), a specific agonist for GABAA receptors, resulted in similar effects as GABA did (n = 29 cells, N = 6 slices). E, F: In contrast, baclofen (100 μM), a specific agonist for GABAB receptors, did not affect the average stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i responses (n = 15 cells, N = 4 slices). The traces in each panel are single cell responses from the same slice.

DISCUSSION

We report three main findings regarding Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons. First, as a novel observation, activation of afferent fibers innervating NM neurons led to transient [Ca2+]i increases in a stimulus frequency- and duration-dependent fashion. Second, the Ca2+ responses were primarily mediated by iGluRs and presumably subsequent activation of VGCCs. Finally, through GABAARs, the GABAergic system impinging on NM neurons modulated their synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ dynamics.

[Ca2+]i increases in response to exogenous glutamate or GABA: comparisons with previous studies

Glutamate, as the sole known excitatory neurotransmitter in avian NM neurons, activates both iGluRs and mGluRs, with the former mediating fast excitatory transmission (Jackson et al., 1985; Zhou and Parks, 1992; Zhang and Trussell, 1994), and the latter being involved in regulating neuronal survival during development (Zirpel et al., 1998, 2000). GABA, as the sole known inhibitory neurotransmitter in NM neurons, activates both GABAARs and GABABRs, with the former mediating a temporally summated sustained inhibition (Monsivais et al., 2000) and the latter being involved in regulating release of glutamate (Otis and Trussell, 1996; Brenowitz et al., 1998; Brenowitz and Trussell, 2001) and GABA (Lu et al., 2005). Activation of these receptors (iGluRs, mGluRs, GABAARs, and GABABRs) by exogenous agonists has been reported to be able to cause [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons (Lachica et al., 1995, 1998; Kato and Rubel, 1999; Zirpel et al., 2000). However, in cultured NM neurons of organotypic preparations, mGluR agonists do not elicit Ca2+ responses (Diaz et al., 2009).

Our results using exogenous agonists for glutamate or GABA receptors were essentially consistent with observations of these previous studies (Lachica et al., 1995, 1998; Kato and Rubel, 1999; Zirpel et al., 2000; Diaz et al., 2009), with two minor discrepancies. First, previous studies (Zirpel et al., 1995; Lachica et al., 1995, 1998) report low sensitivity of [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons in response to exogenous glutamate, i.e., reliable Ca2+ responses are elicited by glutamate at higher (>5 mM) but not lower (100–500 μM) concentrations. In the present study, 100 μM glutamate was sufficient to cause large [Ca2+]i increases in both normal ACSF and Ca2+–free ACSF. Technical differences might account for this discrepancy. We used an upright microscope for the imaging experiments so that bath-applied drugs were able to rapidly reach the slice surface and act on the recorded cells, whereas these authors used an inverted microscope, which may limit the access of bath-applied drugs to the recorded cells in slice preparations. Second, we found that GABA did not induce Ca2+ responses in Ca2+-free ACSF. Lachica et al. (1998) have reported that GABA induces [Ca2+]i increases in Ca2+-free ACSF, likely owing to GABABR-mediated signaling pathways. However, they have also reported in the same paper that GABABR agonist baclofen does not induce Ca2+ responses in Ca2+-free ACSF, an observation confirmed by the present study (Fig. 2G). The definitive reasons for these conflicting results are unclear.

The GABA-induced Ca2+ responses in NM neurons are interesting. It is a well-established phenomenon that GABAA receptors mediate a depolarizing and excitatory action during development, as well as in certain adult brain systems, owing to a relatively high intracellular Cl− concentration (Ben-Ari, 2002). The membrane depolarization induced by GABAA receptors activates VGCCs, causing Ca2+ entry and providing Ca2+ signaling for many developmental events. However, this notion has been challenged recently. The depolarizing and excitatory actions of GABA was attributed to an artifact caused by using energy insufficient ACSF (the standard ACSF containing 10 mM glucose as the sole energy source) in brain slice recordings (Rheims et al., 2009; Holmgren et al., 2010). When 3-β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB, 4 mM) was added to ACSF as an additional energy substrate, both resting membrane potential and the reversal potential for GABA in neocortical pyramidal neurons became significantly more negative (Rheims et al., 2009). When an energy substrate enriched ACSF (eACSF containing 5 mM glucose, 5 mM pyruvate, and 2 mM BHB) replaced the standard ACSF, the sign of the reversal potential for GABA in neocortical and hippocampal neurons was reversed, producing conventional hyperpolarizing inhibition (Holmgren et al., 2010). In response to these challenges, a number of studies presented data supporting the classical view of the depolarizing GABA actions during development (Kirmse et al., 2010; Ruusuvuori et al., 2010; Mukhtarov et al., 2011; Tyzio et al., 2011), resulting in exciting ongoing debates on this issue (Zilberter et al., 2010; Ben-Ari et al., 2011; Khakhalin, 2011). Our results (Fig. 2I, J) provided evidence that the depolarizing effects of GABA in NM neurons persisted into maturation, consistent with previous physiological studies (Lu and Trussell, 2001; Monsivais and Rubel, 2001). Furthermore, the GABA-induced Ca2+ responses were not artifacts caused by insufficient energy sources in the ACSF, supporting the notion that 10 mM glucose is sufficient as the energy source for brain slices in vitro (Tyzio et al., 2011), a case that may be especially valid in avian preparations.

Features and functional significance of synaptic activity-induced Ca2+ responses in NM neurons

Synaptic activity-induced [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons bear three distinct features, which are associated with the intrinsic Ca2+ signaling dynamics and synaptic inputs to NM neurons and are also distinguished from [Ca2+]i increases in response to bath application of neurotransmitter agonists.

First, the [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons due to synaptic activity were transient, with rapid rising and falling time courses. Although there was a dramatic increase in [Ca2+]i increases with increasing stimulus frequency or duration, which is likely due to increased release of neurotransmitters and recruitment of more types of transmitter receptors (Ene et al., 2003), the responses recovered to baseline within several seconds. Even when the stimulation duration was prolonged to 5 s, saturation of [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons did not occur (data not shown). This finding indicates that there exists an extremely effective Ca2+ buffering system in NM neurons to prevent Ca2+ overload for prolonged periods, in agreement with the idea that highly active neurons have powerful Ca2+ buffering machinery. In contrast, low to modest endogenous buffering capability of neurons may be associated with their susceptibility to Ca2+-dependent pathology (Foehring et al., 2009).

Second, although bath application of agonists for either glutamate or GABA receptors caused large and reliable cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i increases in NM neurons, the synaptic stimulation-induced Ca2+ responses were mainly mediated by glutamate receptors, especially iGluRs. The application of GABAAR antagonist, SR 95531, did not on average significantly affect the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases, indicating that the contribution of the GABAergic pathway to the synaptic stimulation-induced Ca2+ responses was minimal under the stimulation conditions. The lack of Ca2+ responses to electrical shocks (train stimulations, 10–100 Hz, duration of 200–1000 ms) applied to the area of the brain slices that presumably contained GABAergic but not glutamatergic fibers innervating the NM further supports this notion (Fig. 4G–J). These observations can be well interpreted with the prior knowledge about the GABAergic transmission in NM. Due to a high intracellular Cl− concentration in NM neurons that persists into maturation of neuronal properties (Lachica et al., 1994; Hyson et al., 1995; Lu and Trussell, 2001; Monsivais and Rubel, 2001), the GABAergic input to the NM is unusually depolarizing, and synaptic activation of the GABAergic input can occasionally evoke action potentials (APs) (Lu and Trussell, 2001). The membrane depolarization and possible spiking activity could activate VGCCs and lead to Ca2+ influx, as shown in developing neurons where GABAergic inputs are excitatory (Leinekugel et al., 1995; Kullmann et al., 2002). NM neurons express both low- and high-threshold VGCCs (Lu and Rubel, 2005), and Ca2+ influx through these VGCCs activated by GABA-mediated depolarization could be a possible source for [Ca2+]i increases. However, due to the dual modulation of the GABAergic transmission by mGluRs and GABABRs (Lu et al., 2005; Lu, 2007), the excitatory action of GABA in NM neurons may be effectively prevented. Without generation of APs, activation of the GABAergic pathway, even at high input frequencies, produces a maximum membrane depolarization of about 15 mV due to temporal summation of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (Yang et al., 1999; Lu, 2009). Given the resting membrane potential of NM neurons between −70 and −65 mV (Lu et al., 2005; Lu, 2007), the membrane would be depolarized to only about −50 mV at maximum shall the GABAergic pathway be fully activated. Membrane depolarization of this amplitude may be likely to activate some of the low-threshold VGCCs (Markram and Sakmann, 1994; Magee et al., 1995), but unlikely to activate the high-threshold VGCCs (Lu and Rubel, 2005). Furthermore because currents mediated by the low-threshold VGCCs in NM neurons are transient (inactivating) (Lu and Rubel, 2005), the amount of Ca2+ entry through these channels is expected to be small. Therefore, Ca2+ influx induced by synaptic activation of the GABAergic pathway for relatively short periods is very limited. This finding is in contrast to the observation of slow [Ca2+]i increases when GABA or muscimol was bath-applied, in which cases prolonged and repeated activation of the GABA receptors and thus accumulated Ca2+ entry may occur, giving rise to Ca2+ responses.

Finally, the GABAergic system modulates synaptic glutamate-induced Ca2+ signaling. The GABAergic inputs, via action of GABAARs, produce a potent inhibitory effect in NM neurons by reducing the input resistance, activating voltage-gated K+ conductances, and inactivating Na+ channels (Lu and Trussell, 2001; Monsivais and Rubel, 2001). A similar inhibitory effect of GABAARs was found here on Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons. Besides generating a slow cytoplasmic [Ca2+]i increase, both GABA and GABAAR agonist muscimol inhibited synaptic stimulation-induced Ca2+ responses in NM neurons. Similar observations have been reported in the developing auditory midbrain inferior colliculus, in which GABAergic or glycinergic inhibitory inputs modulate synaptic glutamate-induced Ca2+ responses, via GABAARs (Lo et al., 1998). In contrast, it is somewhat surprising that activation of GABABRs did not produce inhibitory effects on Ca2+ responses in NM neurons. A possible interpretation may reside in the multiple loci and modulatory functions of GABABRs in the NM. These receptors are expressed on both presynaptic and postsynaptic elements in the NM (Burger et al., 2005b). Presynaptic GABABRs modulate the glutamatergic transmission in NM neurons in a way such that the synaptic depression is substantially suppressed (inhibition of the first EPSC and facilitation of subsequent EPSCs), and the synaptic efficiency and safety factors for spiking are enhanced (Otis and Trussell, 1996; Brenowitz et al., 1998; Brenowitz and Trussell, 2001). In current clamp recordings, the spiking rate in NM neurons is, in contrary to one’s intuition, increased in the presence of GABABR agonists (Brenowitz et al., 1998). Such modulation is expected to cause bidirectional regulation of Ca2+ signaling in response to synaptic activation of the glutamatergic pathway. The inhibition of the initial release of glutamate by GABABRs would reduce Ca2+ responses while the enhancement of the subsequent spike activity would increase Ca2+ responses, resulting in little net effect. Modulation of the GABAergic transmission by presynaptic GABABRs (Lu et al., 2005), and the unknown effects of postsynaptic GABABRs in NM neurons may further complicate the effects of baclofen on the Ca2+ responses. Therefore, activation of GABABRs may alter the synaptic stimulation-induced [Ca2+]i increases in varying directions and degrees, resulting in insignificant differences in statistical averages.

In summary, synaptically released glutamate at the NM triggers [Ca2+]i increases primarily via direct entry through iGluRs and presumably subsequent activation of VGCCs. In contrast, synaptically released GABA does not participate in generating significant Ca2+ signaling in NM neurons. The [Ca2+]i increases elicited by synaptic activation of the glutamatergic system are transient, consistent with the high capability of Ca2+ buffering of NM neurons. Such a transient Ca2+ signaling may confer regulations of cellular processes associated with Ca2+ in a spatially and temporally precise manner. Neural modulation of this Ca2+ signaling by GABAA receptors may play a role in regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in the avian cochlear nucleus neurons.

Highlights.

Synaptic glutamate results in [Ca2+]i increases in avian cochlear nucleus neurons.

Ionotropic glutamate receptors primarily mediate these [Ca2+]i increases.

GABAA receptors inhibit these [Ca2+]i increases, regulating calcium homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Karl Kandler for advice on building up the calcium imaging setup in our laboratory, and Dr. Ivan Milenkovic for helpful discussion on data analysis. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive critics. This work was supported by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant R01 DC008984 to YL.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ACSF

artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- APs

action potentials

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular Ca2+ concentration

- eACSF

energy substrate enriched ACSF

- EPSC

excitatory postsynaptic current

- F340/F380

the ratio of fluorescence intensity of the emission light elicited at 340 nm over that at 380 nm

- GABAAR, GABABR

γ-aminobutyric acid A and B receptor, respectively

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- iGluR, mGluR

ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptor, respectively

- IPSC

inhibitory postsynaptic current

- NL

nucleus laminaris

- NM

nucleus magnocellularis

- SON

superior olivary nucleus

- VGCC

voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ben-Ari Y, Tyzio R, Nehlig A. Excitatory action of GABA on immature neurons is not due to absence of ketone bodies metabolites or other energy substrates. Epilepsia. 2011;52:1544–1558. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodeling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born DE, Durham D, Rubel EW. Afferent influences on brainstem auditory nuclei of the chick: nucleus magnocellularis neuronal activity following cochlea removal. Brain Res. 1991;557:37–47. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90113-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz S, David J, Trussell L. Enhancement of synaptic efficacy by presynaptic GABAB receptors. Neuron. 1998;20:135–141. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80441-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz S, Trussell LO. Minimizing synaptic depression by control of release probability. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1857–1867. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-06-01857.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger RM, Cramer KS, Pfeiffer JD, Rubel EW. Avian superior olivary nucleus provides divergent inhibitory input to parallel auditory pathways. J Comp Neurol. 2005a;481:6–18. doi: 10.1002/cne.20334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger RM, Pfeiffer JD, Westrum LE, Bernard A, Rubel EW. Expression of GABAB receptor in the avian auditory brainstem: ontogeny, afferent deprivation, and ultrastructure. J Comp Neurol. 2005b;489:11–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.20607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XK, Wang LC, Zhou Y, Cai Q, Prakriya M, Duan KL, Sheng ZH, Lingle C, Zhou Z. Activation of GPCRs modulates quantal size in chromaffin cells through Gβγ and PKC. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1160–1168. doi: 10.1038/nn1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz C, Martinez-Galan JR, Juiz JM. Development of glutamate receptors in auditory neurons from long-term organotypic cultures of the embryonic chick hindbrain. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:213–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ene FA, Kullmann PH, Gillespie DC, Kandler K. Glutamatergic calcium responses in the developing lateral superior olive: receptor types and their specific activation by synaptic activity patterns. J Neurophysiol. 2003;90:2581–2591. doi: 10.1152/jn.00238.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foehring RC, Zhang XF, Lee JC, Callaway JC. Endogenous calcium buffering capacity of substantia nigral dopamine neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2326–2333. doi: 10.1152/jn.00038.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui I, Ohmori H. Tonotopic gradients of membrane and synaptic properties for neurons of the chicken nucleus magnocellularis. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7514–7523. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0566-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren CD, Mukhtarov M, Malkov AE, Popova IY, Bregestovski P, Zilberter Y. Energy substrate availability as a determinant of neuronal resting potential, GABA signaling and spontaneous network activity in the neonatal cortex in vitro. J Neurochem. 2010;112:900–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyson RL, Reyes AD, Rubel EW. A depolarizing inhibitory response to GABA in brainstem auditory neurons of the chick. Brain Res. 1995;677:117–26. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00130-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson H, Nemeth EF, Parks TN. Non-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors mediating synaptic transmission in the avian cochlear nucleus: effects of kynurenic acid, dipicolinic acid and streptomycin. Neuroscience. 1985;16:171–179. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato BM, Rubel EW. Glutamate regulates IP3-type and CICR stores in the avian cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:1587–96. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.4.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khakhalin AS. Questioning the depolarizing effects of GABA during early brain development. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1065–1067. doi: 10.1152/jn.00293.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmse K, Witte OW, Holthoff K. GABA depolarizes immature neocortical neurons in the presence of the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16002–16007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2534-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kullmann PH, Ene FA, Kandler K. Glycinergic and GABAergic calcium responses in the developing lateral superior olive. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:1093–1104. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachica EA, Kato BM, Lippe WR, Rubel EW. Glutamatergic and GABAergic agonists increase [Ca2+]i in avian cochlear nucleus neurons. J Neurobiol. 1998;37:321–337. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19981105)37:2<321::aid-neu10>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachica EA, Rübsamen R, Rubel EW. GABAergic terminals in nucleus magnocellularis and laminaris originate from the superior olivary nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1994;348:403–418. doi: 10.1002/cne.903480307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachica EA, Rübsamen R, Zirpel L, Rubel EW. Glutamatergic inhibition of voltage-operated calcium channels in the avian cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci. 1995;15:1724–1734. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01724.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leinekugel X, Tseeb V, Ben-Ari Y, Bregestovski P. Synaptic GABAA activation induces Ca2+ rise in pyramidal cells and interneurons from rat neonatal hippocampal slices. J Physiol. 1995;487:319–329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lips MB, Keller BU. Activity-related calcium dynamics in motoneurons of the nucleus hypoglossus from mouse. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2936–46. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.2936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo YJ, Rao SC, Sanes DH. Modulation of calcium by inhibitory systems in the developing auditory midbrain. Neuroscience. 1998;83:1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00410-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Trussell LO. Mixed excitatory and inhibitory GABA-mediated transmission in chick cochlear nucleus. J Physiol. 2001;535:125–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. Endogenous mGluR activity suppresses GABAergic transmission in avian cochlear nucleus magnocellularis neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:1018–1029. doi: 10.1152/jn.00883.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y. Regulation of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission in the chick nucleus laminaris: role of N-type calcium channels. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1009–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Burger RM, Rubel EW. GABA(B) receptor activation modulates GABA(A) receptor-mediated inhibition in chicken nucleus magnocellularis neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1429–1438. doi: 10.1152/jn.00786.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Rubel EW. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits high-voltage-gated calcium channel currents of chicken nucleus magnocellularis neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1418–1428. doi: 10.1152/jn.00659.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee JC, Christofi G, Miyakawa H, Christie B, Lasser-Ross N, Johnston D. Subthreshold synaptic activation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels mediates a localized Ca2+ influx into the dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1335–1342. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.3.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Sakmann B. Calcium transients in dendrites of neocortical neurons evoked by single subthreshold excitatory postsynaptic potentials via low-voltage-activated calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5207–5211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic I, Rinke I, Witte M, Dietz B, Rübsamen R. P2 receptor-mediated signaling in spherical bushy cells of the mammalian cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:1821–1833. doi: 10.1152/jn.00186.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsivais P, Rubel EW. Accomodation enhances depolarizing inhibition in central neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7823–7830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07823.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monsivais P, Yang L, Rubel EW. GABAergic inhibition in nucleus magnocellularis: implications for phase locking in the avian auditory brainstem. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2954–2963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02954.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otis TS, Trussell LO. Inhibition of transmitter release shortens the duration of the excitatory synaptic current at a calyceal synapse. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:3584–3588. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks TN. Morphology of axosomatic endings in an avian cochlear nucleus: nucleus magnocellularis of the chicken. J Comp Neurol. 1981;203:425–440. doi: 10.1002/cne.902030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks TN. The AMPA receptors of auditory neurons. Hear Res. 2000;147:77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheims S, Holmgren CD, Chazal G, Mulder J, Harkany T, Zilberter T, Zilberter Y. GABA action in immature neocortical neurons directly depends on the availability of ketone bodies. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1330–1338. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EW, Fritzsch B. Auditory system development: primary auditory neurons and their targets. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:51–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruusuvuori E, Kirilkin I, Pandya N, Kaila K. Spontaneous network events driven by depolarizing GABA action in neonatal hippocampal slices are not attributable to deficient mitochondrial energy metabolism. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15638–15642. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3355-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szydlowska K, Tymianski M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZQ, Gao H, Lu Y. Control of a depolarizing GABAergic input in an auditory coincidence detection circuit. J Neurophysiol. 2009;102:1672–1683. doi: 10.1152/jn.00419.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang ZQ, Hoang Dinh E, Shi W, Lu Y. Ambient GABA-activated tonic inhibition sharpens auditory coincidence detection via a depolarizing shunting mechanism. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6121–6131. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4733-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyzio R, Allene C, Nardou R, Picardo MA, Yamamoto S, Sivakumaran S, Caiati MD, Rheims S, Minlebaev M, Milh M, Ferré P, Khazipov R, Romette JL, Lorquin J, Cossart R, Khalilov I, Nehlig A, Cherubini E, Ben-Ari Y. Depolarizing actions of GABA in immature neurons depend neither on ketone bodies nor on pyruvate. J Neurosci. 2011;31:34–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3314-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME, Dallos P. Neural coding in the chick cochlear nucleus. J Comp Physiol [A] 1990;166:721–734. doi: 10.1007/BF00240021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Monsivais P, Rubel EW. The superior olivary nucleus and its influence on nucleus laminaris: a source of inhibitory feedback for coincidence detection in the avian auditory brainstem. J Neurosci. 1999;19:2313–2325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-02313.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye JH, Zhang J, Xiao C, Kong JQ. Patch-clamp studies in the CNS illustrate a simple new method for obtaining viable neurons in rat brain slices: glycerol replacement of NaCl protects CNS neurons. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;158:251–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HZ, Sensi SL, Ogoshi F, Weiss JH. Blockade of Ca2+-permeable AMPA/kainate channels decreases oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced Zn2+ accumulation and neuronal loss in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1273–1279. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-04-01273.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young SR, Rubel EW. Frequency-specific projections of individual neurons in chick brainstem auditory nuclei. J Neurosci. 1983;3:1373–1378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-07-01373.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Trussell LO. A characterization of excitatory postsynaptic potentials in the avian nucleus magnocellularis. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:705–718. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.2.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou N, Parks TN. Developmental changes in the effects of drugs acting at NMDA or non-NMDA receptors on synaptic transmission in the chick cochlear nucleus (nuc magnocellularis) Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1992;67:145–152. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(92)90215-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilberter Y, Zilberter T, Bregestovski P. Neuronal activity in vitro and the in vivo reality: the role of energy homeostasis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirpel L, Janowiak MA, Taylor DA, Parks TN. Developmental changes in metabotropic glutamate receptor-mediated calcium homeostasis. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:95–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirpel L, Lachica EA, Rubel EW. Activation of a metabotropic glutamate receptor increases intracellular calcium concentrations in neurons of the avian cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci. 1995;15:214–222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00214.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirpel L, Lippe WR, Rubel EW. Activity-dependent regulation of [Ca2+]i in avian cochlear nucleus neurons: roles of protein kinases A and C and relation to cell death. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:2288–2302. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.5.2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]