Abstract

Metabolites and peptides play important roles in almost every aspect of cell function. Their intracellular levels and spatial localizations reflect the state of each cell and its relationship to its surrounding environment. Moreover, their levels and dynamics are indicative of normal or pathological cellular conditions. Bioanalytical technologies for microanalysis are able to qualitatively and quantitatively characterize subsets of peptides and metabolites from individual microorganism, plant and animal cells. Highlighted here are the established and evolving strategies for characterization of the metabolome and peptidome of single cells. Focused studies of the chemical composition of individual cells and their networks promise to provide a greater understanding of cellular fate, function, and homeostatic balance. Single cell bioanalytical microanalysis has also become increasingly valuable for examining cellular heterogeneity, particularly in the fields of neuroscience, stem cell biology, and developmental biology.

Why study single cells?

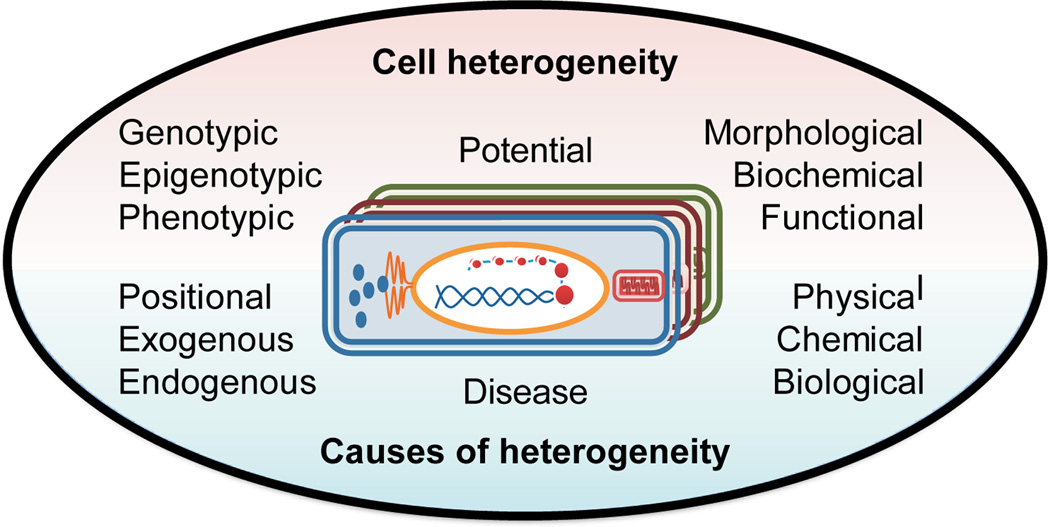

Targeted measurements of single cells in animals not only serve to further our understanding of biological variability and differential susceptibility to disease and treatment, they help us to understand heterogeneity among similar cells. For decades, investigations comparing supposedly homogeneous multicellular samples and selected individual cells have documented their cellular heterogeneity. Single cell studies revealed the process of cell excitability using molluskan neurons1 and were also critical in the discovery of the mechanisms of vision,2 where only particular cells in a cellular population were found to be involved in the recognition of a specific pattern. Importantly, heterogeneity in the molecular organization among cells underlies individual variability in the activity of cellular networks and circuits.3 Consider a metabolic pathway such as NO production in nitrergic cells, perhaps present in less than 1% of the neurons in a brain region. If only rare nitrergic neurons have high levels of the NO decomposition products nitrite and nitrate, then regional measurements of low micromolar levels of these two compounds imply nitrergic cell levels of millimolar, a value that impacts many other pathways. With single cell measurements from larger invertebrate neurons, cellular heterogeneity in NO producing neurons has been shown to occur.4 Heterogeneity may result from genetic, structural or functional differences within a cell population (Fig. 1) and can develop in systematic or stochastic ways. Ultimately, cellular heterogeneity becomes evident at the chemical level. Recognizing the similarities and differences between distinct cells, each specialized for a specific role within the organism, can lead to unique insights into the functioning of an entire system. Even in the mammalian brain, which contains trillions of cells and demonstrates a high level of redundancy, activation of a single neuron can evoke a complete motor action (e.g., whisker movement5) and stimulation of single neurons in the somatosensory cortex affects behavioral responses in rats.6 Stem cells present one of the more striking examples of the potential of heterogeneity to manifest in unique functional outcomes. For example, individual adult stem cells transplanted in vivo can generate a prostate7 or a functioning mammary gland.8 Such remarkable developments occur in part because of significant changes in the cellular biochemistry of stem cells. Thus, investigating the chemical similarities and differences between individual cells is clearly an important research area, one which requires specific methodologies that can address small sample volumes in a wide variety of analytes.

Figure 1.

Cell-to-cell heterogeneity has many different manifestations and causes. "Potential heterogeneity" reflects the cell’s capability to change its function, chemical composition, and structure under influences of its physical and chemical environments. One goal of metabolomics/peptidomics is to enable predictions on which cell(s) will become cancerous and to determine what extracellular or intracellular stimuli are needed for this transformation.

What are the Metabolome and Peptidome?

The metabolome represents the set of small molecules, or metabolites, in a cell that are often defined as those with a molecular mass below 1 kDa. RNA molecules are part of the cellular transcriptome and typically are not included in the metabolome. The peptidome of an individual cell comprises the set of 2 to 50-amino-acid-residues-long peptide gene products. Cellular metabolites and peptides can be exogenous or endogenous in nature. Exogenous compounds originate outside of the organism of interest; they are frequently termed xenobiotics, and more specifically, xenometabolites and xenopeptides. An estimate of the number of endogenous metabolites discussed in the literature approaches a million.9 However, current metabolite databases contain only several tens of thousands of these compounds. Nonetheless, many of the molecules detected in metabolomic experiments, especially those performed at the single cell level, remain unidentified. It is not surprising that these studies present challenges; determination of an unknown metabolite often requires significant investments in time and resources, as well as demanding greater sample amounts.

The total number of naturally occurring peptides is large, in part, because of protein degradation, as well as posttranslational modifications of the degrading proteins. Current peptide databases mostly list molecules that have been characterized as physiologically or putatively active. Prohormones that encode several hundred peptides potentially involved in cell-to-cell signaling in the nervous system of common neuronal model species are described in NeuroPred (http://neuroproteomics.scs.illinois.edu/neuropred.html). The SwePep database lists thousands of unique, biologically relevant peptides (http://www.swepep.org/). One of the largest sources of information on endogenous peptides, PepBank, references more than 21,000 peptides (http://pepbank.mgh.harvard.edu/). The diversity of metabolites and peptides is staggering. However, considering the small volume (femtoliter range) and weight (femtogram range) of an average cell, only a limited number of abundant substances with diverse physicochemical parameters will "fit" within the cell. Schmid et al.10 calculated that a typical mammalian cell, 10 µm in diameter, has a volume of 500 fL and a weight of 100 pg when dried, and contains 10 pg of carbohydrates, 1010 molecules of lipids, and 109 protein molecules with ~100,000 copies per protein of 1,000 proteins.10 Intracellular concentrations of amino acids are in the low millimolar to high micromolar range for murine hybridoma cells.11 Other examples from the literature demonstrate that molecular concentrations in different cells are wide ranging. An average human erythrocyte contains 60 ± 30 amol of glutathione;12 even a single molecule in a 60 fL erythrocyte will be present at about a nanomolar concentration, so that lower concentration measurements are not needed. Similarly, a PC12 cell includes 3.5 ± 3 fmol of glutamic acid,13 and larger neurons can contain femtomole levels of select neuropeptides.14

Capillary electrophoresis is one of several methods that has come close to the single molecule detection level, enabling analysis of yoctomole amounts of analytes from a cell.15 The approach has advanced single cell metabolomics and peptidomics (SCMP) to the ability to assay selected analytes in individual organelles.16 Multiple levels of the chemical organization of individual cells are the focus of 'omics technologies,17 including genomics, epigenomics (see www.roadmapepigenomics.org), transcriptomics, proteomics, peptidomics, metabolomics, and metallomics/elementomics. In this review, we focus on the strategies used for metabolomic and peptidomic analyses of single cells.

Single cell metabolomics and peptidomics

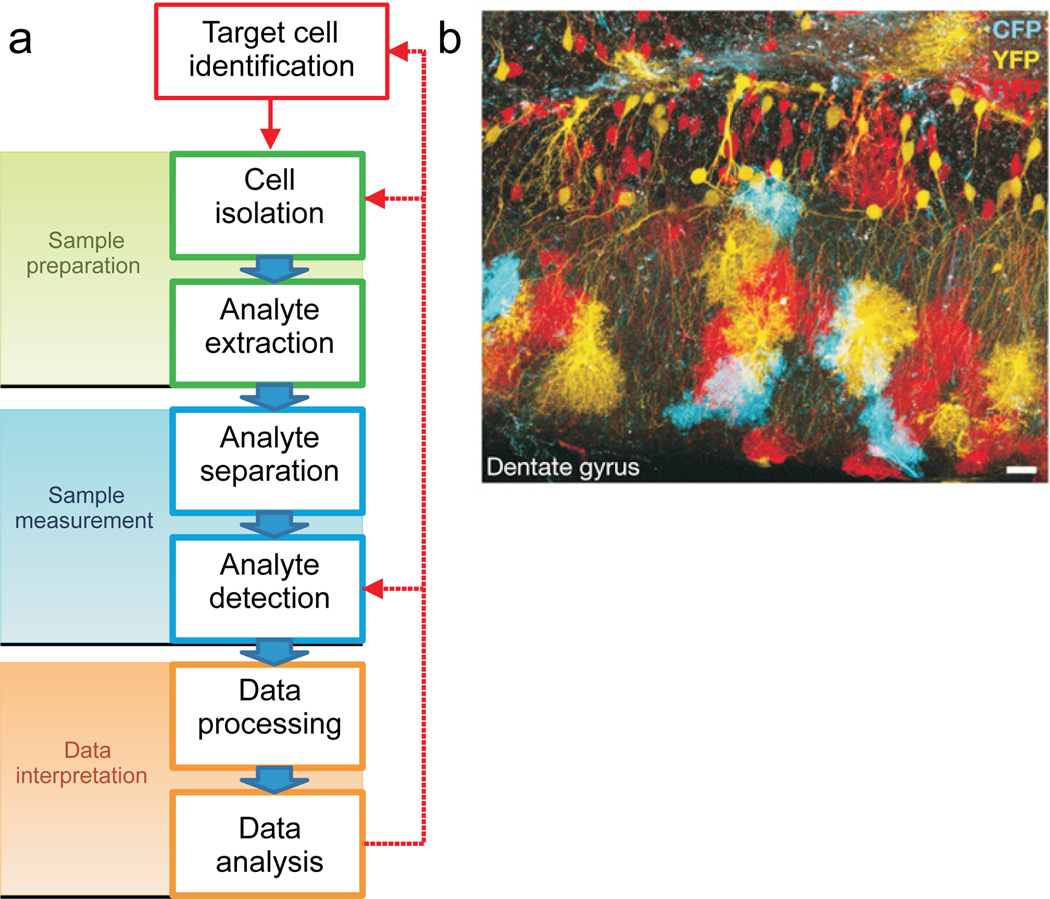

The development and application of specific analytical approaches in SCMP include addressing the inherent biological, physical, and chemical challenges, and elicit several specific questions. What is the best approach for identifying the cell of interest? How can this cell be isolated from its morphologically and chemically complex environment without perturbing its contents? Which methods should be used to extract, measure and identify small amounts of cellular analytes? Of the available bioanalytical tools, which provide the sensitivity and selectivity needed, and also meet the appropriate minimal sample volume requirements for the planned single cell investigation? In addition to considering the significant investments in hardware, expertise and time needed to accomplish an SCMP study, answering these questions during the project planning phase is critical—the experimental protocol must be optimized for the specific cell type being examined. The general workflow of an SCMP experiment, as outlined in Fig. 2a, is described below.

Figure 2.

A variety of approaches allow the visualization of cells to enable subsequent isolation and characterization. (a) Typical workflow for single-cell metabolomic and/or peptidomic analysis outlining the major experimental steps; cell-selection approaches are greatly aided when the cells are labeled. (b) The Brainbow mouse involves the stochastic combinatorial expression of multiple fluorescent proteins, with neurons and astrocytes from the dentate gyrus shown here; such labeling schemes allow selection of specific cells for assay. Used with permission from Nature Publications.26

Target cell identification

The first step for many SCMP experiments is to identify the cell(s) of interest, especially when working with rare or unique cells. A straightforward and reliable method for targeted cell identification is visual observation and is suitable for the sampling of extraordinary cells such as giant neurons of mollusks, or morphologically distinct cells such as Purkinje neurons of the rat cerebellum. More sophisticated cell localization approaches are needed when targeting individual cells from populations of morphologically similar cells. Cell-specific labeling methods, exogenous and endogenous, facilitate cell discrimination.

One approach for exogenous labeling relies on cell surface markers that are recognized by antibodies or aptamers. It is widely used for in vivo and in vitro tracking of various cells via conjugated fluorescent secondary labels and fluorescent or magnetic nanoparticles18,19 and is often applied in stem cell sorting experiments.20 Another means of cell labeling utilizes preferential uptake and accumulation of a synthetic label by a subtype of cells with certain attributes. Fluorescent molecules, labeled latex beads, and gold or virus nanoparticles have been employed as exogenous labels. Nanoparticles are useful in following cell localization in organs and tissues of live organisms with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Targeted MRI investigations are possible with the use of specific molecular probes, such as antibodies, linked to ultra small super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles.21 These markers can be injected into living organisms, concentrated on target cells and visualized by MRI, as demonstrated for tumor cell localization.21 Alternatively, nanoparticles are loaded into live cells and the cells are then injected into an organism where distribution is followed with MRI.22

The uptake (or intracellular injection) of neuroanatomical tracers into neurons or their neurites has allowed labeling of the cell of interest via tracer intracellular transport or diffusion.23,24 As an example, the backfill of neurons with neuroanatomical tracers enabled the isolation of specific insect (Periplaneta americana) neurons; 22 distinct FMRFamide-related peptides were detected in these individual neurons using matrix-assisted laser desorption / ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry (MS).25

Endogenous labeling primarily relies on molecular biology approaches that use the expression of fluorescent gene reporters in selected cell types within a tissue. One of the most exciting examples of this is the Brainbow mouse—a strain with a multitude of fluorescent labels that have been genetically encoded and expressed in a stochastic manner at varying concentration levels in different neurons (Fig. 2b).26 In these mice, numerous neighboring neurons each have a uniquely colored fluorescence that distinguish them individually, as well as differentiate them from glia. Similarly, random Golgi-like stable neuron labeling has been achieved via expression of green, cyan or yellow fluorescent proteins in unique subpopulations of neurons.27 New molecular biology tools such as genetic tracing28 allow visualization of specific postsynaptic and presynaptic populations of cells. Development of the Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers29 and Single-Neuron Labeling with Inducible Cre-Mediated Knockout30 methods further empower single cell analysis by effecting selective gene knockout in a subpopulation of mouse fluorescent cells. Successful use of endogenous labeling for target cell identification in SCMP studies has been demonstrated for insect31 and mammalian32 cells.

Alternatively, one can employ a more general, multiparametric approach for cell identification; characteristics such as size, density, shape, and rigidity can often be sufficient for finding the target cell in certain models. For example, mouse embryonic stem cells have been selected using sedimentation field-flow fractionation, or SdFFF.33 Determination of cells of interest also can be done post hoc, for example, by the presence of known cell-specific metabolites.

While characterizing small numbers of cells can reveal important information, high-throughput technologies are needed for many applications. As it stands currently, single cell measurement technologies tend to enable either fast characterization of cells with relatively few (preselected) channels of information such as in flow cytometry, or yield higher information content but with lower throughput profiling as obtained with mass spectrometry.

Cell isolation

Once the targeted cell has been localized, metabolite and peptide profiles can be measured in the cell of interest while it remains inside the larger tissue sample. Alternatively, the collection/isolation process can be used to deliver the cell to an analytical instrument. Single cell sample isolation is an especially demanding procedure because the cellular metabolome and peptidome are variable and sensitive to sampling-related perturbations such as temperature changes, enzyme or chemical treatments, and mechanical manipulations. Thus, it is vital to reduce intracellular biochemical activity and damage-induced analyte loss during this process. There are numerous approaches for reducing isolation-related perturbation in the cellular metabolome and peptidome. For example, lower temperatures decrease metabolic activity, while cell heating prevents proteolytic degradation of ubiquitous proteins. Additionally, a low-calcium medium may reduce undesirable release of analytes from neurons.

Manual methods of single cell sample preparation34–37 often follow the classical protocols established by Otto Friedrich Karl Deiters, who used sharp needles for cell isolation without enzymatic pretreatment of the tissue.38 Other common practices use enzymes to facilitate tissue dissociation— protease- or DNAse-treatment enabled isolation of cells from brain, muscle, and liver39 and enzymatic digestion generated thousands to millions of cells for high-throughput cell sorting techniques such as flow cytometry.40

Perhaps the prototypical approach for characterizing individual cells is flow cytometry; greater numbers of fluorescent barcodes increase the information content so that cells can be characterized as well as sorted in an efficient manner.41 The development of microfluidic cell sorters42,43 has enabled cell collection, lysis, analyte separation and detection to be performed on a single device. Although one tends to think of flow cytometry as high throughput but not information rich, methods are becoming available for adding greater numbers of channels, or measured cellular parameters, so that cells can be sorted and typed. In fact, even specific cellular conditions such as selected phosphorylation states can be determined.44 Recent enhancements include the interface of flow cytometry to time-of-flight (TOF) MS, with this approach yielding up to 100 channels of chemical information as well as determination of cell type.45 When fully developed, this technology should offer unprecedented throughput in combination with chemical information to allow a fundamentally increased level of insight into cellular heterogeneity.

Analyte extraction

When an SCMP investigation is performed using invasive or destructive technologies, analyte extraction from the target cells becomes a crucial experimental step. This is because the measurement accuracy depends not only on the detection method but also on the efficiency of the analyte extraction. Likewise, the speed and efficiency of quenching the cell isolation-related changes impacting the intracellular metabolic activity is important. Recovery of intracellular analytes from single cells is often achieved either by lysis46 or by using chemical agents to make cellular membranes permeable to analytes. The various approaches employed for SCMP studies utilize different operating principles to facilitate analyte extraction, and are selected based on cell type.

Physical lysis methods include high-strength electrical fields applied to cells in microfluidic devices,47 laser-induced lysis,48 lysis by freezing and/or thawing,49 and cell disruption by rapid decompression, osmotic shock, or mechanical means. Alternatively, enzymatic lysis or treatment with detergents is also used. Different cell types require different lysis protocols. Importantly, not all lysis methods are compatible with all of the analyte separation and detection modalities and thus must be carefully chosen. High detergent or inorganic salt concentrations may interfere with analyte desorption/ionization for mass spectrometric detection, and higher viscosity and salt content can detrimentally affect electrophoretic separations in capillaries or microfluidic devices.

Many analyte extraction protocols are biased for a specific class of compounds (e.g., lipids, sugars, gaseous free radicals). This bias has several causes, including the exceptionally diverse physicochemical parameters of cellular metabolites and peptides as well as their dynamic binding/incorporation into different intracellular matrices and structures. Often, multiple extraction protocols are used in a single SCMP investigation for more complete metabolome coverage. However, the limited size of single cell samples and amount of available analytes makes application of multiple extraction protocols in SCMP difficult, in part due to analyte loss. Application of radioactive or fluorescent internal standards as well as the use of microfluidic devices may partially alleviate this problem by allowing optimization of each step of the extraction protocol and creating confined, small volume spaces for analyte extraction and manipulation.

When working with hundreds of dynamically changing compounds within the cell, enzymatic activity must be quenched in order to avoid changes in the metabolome and peptidome that occur during the cell sampling and analyte extraction processes. Methanol/waterbased mixtures are more frequently used for metabolite extraction, especially as methanol works well to quench metabolic activity. Mixtures of methanol, chloroform, and water (1:1:1, v/v/v) have been applied successfully for simultaneous extraction of lipophilic and hydrophilic metabolites from cultured M2R mouse melanoma cells.50 Peptides can be extracted by acidified methanol or acidified acetone solutions. In peptide extraction experiments using an aqueous solution of 2,5 dihydroxybenzoic acid, it has been shown that that multistage analyte extraction improves the peptidome coverage.37 Molecules that are difficult to manage in a metabolomic investigation include short-lived metabolites such as endogenous nitric oxide and carbon monoxide, which are both highly reactive species. To address this issue, either markers for the compounds or selective sensors can be positioned nearby the cell of interest before its lysis.51

Separation and Detection: Characterization of Peptides and Metabolites in a Cell

The analytical approach of choice for an SCMP investigation depends on the goals of the study. Profiling experiments allow comparison of the metabolomes or peptidomes of cells without analyte identification (e.g., biomarker discovery) and generate lists of signals/compounds for further examination. Qualitative analyses aim to identify as many analytes as possible, whereas quantitative metabolomics and peptidomics measure absolute or relative concentrations of a chemical species. The main trend in SCMP has been a greater focus on analyte identification and its relative quantitation, both of which emphasize information-rich approaches such as MS. Not surprisingly, the small amounts of analytes present in a cell, as well as the unavailability of relative standards, make absolute quantitation of many compounds difficult.

Depending on the specific technologies used, SCMP approaches can be divided into noninvasive and invasive. Noninvasive methods maintain the anatomical and functional integrity of the cell, and achieve analysis in vivo. In contrast, invasive methods extract analytes from the cell and destroy its integrity.

Noninvasive approaches

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is an excellent example of a noninvasive, quantitative method of analyte detection. It has recently been used for SCMP analyses of individual cells,52,53 predominantly, for metabolite detection in individual larger cells such as Xenopus laevis oocytes54 and Aplysia californica neurons.55 Because of sensitivity issues, NMR spectroscopy tends to provide low coverage of the metabolome. However, enhancements in NMR sensitivity have been achieved with new probe technologies such as microcoils that allow 10 pmol analyte detection56 and microslot waveguide probes which enable detection of ~1 nmol RNase A.57 These small-volume NMR probes enhance the detection limits of NMR and allow the characterization of cell-sized samples.58,59

A limited number of analytes can also be specifically detected in single cells with high sensitivity using intracellular fluorescent probes that are loaded into or expressed inside of cells.51,60 It is feasible to design a system that utilizes both NMR spectroscopy and fluorescent probes to simultaneously follow the concentration changes of several metabolites of different abundances. There are a number of chemical imaging methods that allow metabolite detection in live cells, even inside an organism. For example, the observation of lipids and other metabolites in a single cell can be achieved using infrared, Raman, stimulated Raman scattering, and coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering imaging. However, these approaches produce chemical information that is typically insufficient for identification of analytes in cells. This issue is addressed when combining these approaches with other techniques, as described below.

Invasive approaches

When using invasive SCMP methods, analytes are removed from the cell(s) for characterization. In MS, for example, analytes are transferred into the gas phase, ionized, separated by their mass-to-charge ratios, and ultimately detected.61 Three of the more common categories of invasive SCMP approaches are highlighted below: chromatography and electrophoresis, microfluidics and lab on a chip, and direct MS.

Chromatography and electrophoresis

Chromatography and electrophoresis are two chemical separations well suited for SCMP experiments because they have favorable scaling laws for miniaturization and reduce the complexity of the sample before detection. Multiple techniques are often combined to create hyphenated systems, allowing them to characterize even more complex samples. Gas chromatography (GC), capillary electrophoresis (CE) and liquid chromatography (LC) are three effective separation approaches used in SCMP investigations. After separation, single cell analytes are detected using a variety of methods including MS, amperometry, or fluorescence detection.

There have been a number of representative SCMP studies utilizing chromatography or electrophoresis. Neurotransmitters and their precursors have been characterized in single neurons of the mollusk Helix aspersa with open tubular LC and voltammetric detection.62 Nano-high performance LC hyphenated to electrospray ionization (ESI) MS provided quantitative and qualitative data for the identification of pigments in cells of the Torenia plant.63 A number of peptides were detected in a cell using microcolumn LC linked off-line to MALDI TOF MS.64 Historically, GC with electron capture detection was introduced in the late 1960s65 and only a few years later, the amino-acids in single neurons of A. californica were characterized with GC-MS.66

CE with laser-induced fluorescence detection is one of most versatile and sensitive SCMP approaches,67 allowing quantitation of yoctomole amounts of analytes68 in complex samples. Using these approaches, a wide range of analytes, including chiral molecules such as L- and D-amino acids69 and aromatic species70 have been investigated at the single-cell level. The combination of single-cell CE and ESI-MS was used to assay mammalian erythrocytes,71 and more recently, CE-ESI MS facilitated the chemical analysis of individual neurons of the A. californica central nervous system.72

Microfluidics and lab-on-a-chip

Analyte amounts present in a single cell and the high complexity of the cellular metabolome and peptidome, together require efficient cell lysis, analyte extraction with minimal dilution, high resolution separation, and sensitive detection. Microfluidic devices provide a unique opportunity to meet these goals. They offer small internal surface areas and low-volume interfaces among the various functional units of the devices (e.g., microchambers for cell culture and channels for analyte capture and/or separation), resulting in negligible analyte losses, a low degree of dilution, and fast multidimensional separations. Because their physical dimensions match those of both the cell sample and many microanalytical detection techniques, microfluidics are easily integrated with different off-chip detection modalities, including MS and fluorescence spectroscopy.73

A variety of microfluidic device designs have been developed and applied in metabolomics investigations,74 and are used for SCMP studies of the cell secretome. For example, Jo et al75 presented a microfluidic device in which a live neuron was positioned, stimulated, and the released neuropeptides captured downstream on a C18-coated surface (Fig. 3), allowing their analysis via off-line MALDI MS imaging. Metabolite fluxes from single cells can also be studied. A single beating cardiomyocyte placed in a polydimethylsiloxane device releases lactate upon electropermeabilization, and was measured in real-time with an electrochemical lactate microbiosensor.76 With the addition of “on-chip” cell lysis/extraction steps, these experimental designs are well-suited for studies of the cellular metabolome or peptidome. For example, microfluidic devices were used for the rapid lysis of single human erythrocytes and electrophoretic separation of released cellular biomolecules.73 Eluting compounds were ionized by an integrated electrospray emitter and the generated ions were mass analyzed, with cell counts as high as 12 per min. Separation of analytes undoubtedly improves molecular identifications and can advance quantification in MS experiments.

Figure 3.

Microfluidic devices are of growing importance in SCMP investigations. Here, a microfluidic device with functionalized gold surfaces allows chemical stimulation of individual cultured neurons, collection of stimulated release, and characterization of released peptides using off-line mass spectrometry. (a) Schematic of the device containing a cell compartment and three fluidic channels used for released peptide collection. (b) Cultured neuron in the microchannel prior to stimulation. Scale bar = 100 μm. (c) MS image of the (1) prestimulation, (2) stimulation, and (3) poststimulation channels showing that peptides are only collected during chemical stimulation of the neuron. (d) Representative mass spectra of the prestimulation channel showing only background peaks (top) and from the stimulation channel showing several known neuropeptide peaks (bottom). Used with permission from the Royal Society of Chemistry.75

An on-chip cell viability assay combined with a microdroplet workflow enabled mammalian cell cytotoxicity studies and combinatorial screening at a high-throughput.77 These manipulations can further aid the chemical analysis of cell content when combined with appropriate separation/detection techniques including CE, MS, and spectroscopy. As one example, Raman spectroscopy is a nondestructive analytical method that has already shown success in fingerprinting, quantifying, and even three-dimensionally imaging distributions of selected molecules (reviewed in Brehm-Stecher et al.78). In a recent development, individual living microalgal cells were laser-trapped and analyzed by Raman methods.79 These data not only provide insight into the lipid content but also yield information on the relative concentration of lipids within the cell.

Direct-tissue mass spectrometry

Perhaps one of the most successful SCMP approaches is single cell MS. Accurate mass measurements of intact molecules and their fragments have made MS an indispensible research tool in metabolite and peptide characterization. While some modalities of MS involve transferring the single cell sample to a vacuum system for analysis, others are capable of performing measurements at atmospheric pressure.

Among the vacuum MS methods, secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) and MALDI have become instrumental in single cell investigations. SIMS utilizes a highly focused beam of energetic primary ions that bombard the sample surface, sputtering secondary ions for massanalysis. Offering exquisite lateral resolution, TOF SIMS provides a unique way to study the spatial localization of chemical species with a molecular mass below ~1,000 Da in single cells.61 SIMS is the method of choice to analyze the lipid composition of cellular membranes, in part due to its high sensitivity for many lipids and their fragments. As a milestone in the study of molecular mechanisms of cellular membrane shaping, SIMS revealed the time-dependent chemical composition of membranes in the unicellular organism Tetrahymena thermophila.80 It was determined that the formation of membrane lipid domains followed structural changes taking place during the mating process (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

A variety of vacuum-based MS methods have been used for single-cell SCMP investigations. (a) Secondary ion MS is used to visualize and identify the phospholipid distribution changes that occur during conjugation of the Tetrahymena thermophila (top panel). Normalized phosphatidylcholine ion images and (bottom panel) line scans for the phosphatidylcholine and C5H9 across cell–cell junctions at 1 h and 3 h, respectively, reveal the temporal evolution of the lipid domains formed during these processes. Scale bar denotes 50 μm. Used with permission by the National Academy of Sciences.80 (b) MALDI MS reveals the metabolic individuality of Closterium acerosum cells (microscope pictures in inset) obtained from different cultures (top to bottom). For reference, the lowest trace shows a spectrum from the blank (no cell deposited on the MALDI plate). Yellow bars highlight spectral features associated with the cells. The scale bar denotes 200 μm. Used with permission from the American Chemical Society.87 (c) Relative quantification of neuropeptides is possible using MALDI MS of single neurons via appropriate labeling reactions. Top mass spectrum represents the peptide profile of an individual CFT neuron before labeling. Two bottom mass spectra acquired from mixtures of two different pairs of CFT cells, enabling changes in peptide contents between cells to be measured. Used with permission from the American Chemical Society.90

Recent methodological advances allowed SIMS to be used for the three-dimensional chemical imaging of cell structures. Vickerman and co-workers81 have probed the threedimensional organization of isolated Xenopus laevis oocytes using a depth profiling approach. SIMS imaging has also been used to observe the subcellular localization of a number of compounds, including vitamin E in the cellular membrane of individual isolated neurons from A. californica.82

Laser desorption ionization (LDI) encompasses a range of MS techniques. Perhaps the earliest examples of single cell LDI MS were reported in the work of Hillenkamp and colleagues.83 A laser beam with a 5-µm-diameter probed the chemistry of thin tissue slices and various metabolites were detected in different regions of single cells. Several powerful analyte desorption/ionization approaches have subsequently been developed and applied to investigate peptides and metabolites in single cells. Direct desorption of silicon84 has been used to study cultured neurons.85 The exciting work of Siuzdak86 resulted in the introduction of clathrate nanostructures-based analyte desorption/ionization (nanostructure-initiator mass spectrometry, or NIMS). NIMS achieves ion generation via a molecular interplay with initiator molecules trapped within the substrate that can help map out the metabolite and peptide content of single cells with 150-nm resolution in the ion-mode.86

MALDI MS is a powerful analytical approach for simultaneously characterizing a broad range of analytes including metabolites, peptides and proteins. It is also amenable to a wide range of biological sample types and is, perhaps, the most frequently used technique for MSbased single cell analysis. This success is due, in part, to its simplicity of use, the availability of high performance instruments, and the unsurpassed capability of MALDI MS to analyze small quantities of analytes from chemically heterogeneous samples (Fig. 4b).87 MALDI MS detects and characterizes unlabeled compounds that can influence the activity of cellular circuits/pathways. As an example, single-cell MALDI-TOF MS was used to monitor temporal changes in intracellular histamine levels in the mouse bone marrow-derived mast cell during the maturation process.88 Furthermore, lowering the sample size and volume to the single micron scale and attoliter to femtoliter volume regime, MALDI MS has opened the door for peptide profiling from individual A. californica atrial gland secretory organelles.89 More than ten peptides from four separate genes were detected within each vesicle. With the advent of in situ, in vitro, and in vivo isotope labeling protocols, mass spectrometric methods have become well suited for quantitative or semiquantitative analysis of volume-limited samples. Stable isotope labeling with d0- and d4-succinic anhydride and iTRAQ reagents was adapted for relative quantitation of insulin Cβ peptide in individual neurons (Fig. 4c).90

MS-based determinants of the distributions of intact biomolecules with subcellular spatial resolution is a rapidly developing approach that can be adapted to single cell studies. The combination of scanning laser microprobe mass analysis and MALDI is particularly attractive for future applications as this synergy results in the high lateral resolving power (~1μm) offered by near-field effects and the ability to detect large peptides and proteins. As an example, Bouschen et al.91 demonstrated the potential of scanning microprobe MALDI, or SMALDI, by chemically imaging human renal carcinoma cells with 2 μm resolution. In addition, a variety of MALDI matrix deposition techniques can be explored in the future to tailor ion generation for a selected subset of compounds in SCMP experiments.

Ambient MS SCMP can be also performed in a direct fashion without analyte separation.92 For example, live video-MS is one such method that employs a metal-coated micropipette to sample visually selected areas of live individual cells. These samples are then directly electrosprayed from a micropipette into a mass analyzer. This approach enables direct interrogation of the microgranules of mast cells (Fig. 5a). Serotonin and histamine, known mediators in allergy stimulation, were detected and identified.93

Figure 5.

Ambient ionization MS allows fast sampling from living single cells followed by immediate sample analysis. (a) Video-MS probes (left middle panel) the granules from a mast cell and identifies (left bottom panel) histamine by tandem MS. Adapted with permission from Wiley-Blackwell.93 (b) LAESI MS interrogates a single cell of an Allium cepa cultivar in noncontact mode (left panel) showing a sharpened optical fiber, and yielding mass spectra that reveal different metabolic composition for neighboring (middle panel) colorless and (right panel) pigmented epidermal cells, with the optical image of the cells in the inset (scale bar = 50 μm). Adapted with permission from the American Chemical Society.98

A fundamentally different approach for the characterization of biomolecules in real time is becoming possible with the advent of the nanoelectromechanical system (NEMS).94 NEMS combines molecular transfer and detection in a single step; molecules are directly weighted in this approach. Roukes and colleagues94 used an electrospray injection system to deliver and measure single-molecule absorption events for the protein bovine serum albumin with a mass resolution of 1,000 Da. Well-suited for protein detection, NEMS is expected to provide a mass resolution below 1 Da and an accuracy of 100 ppm for 100 kDa proteins. The use of nanowires and nanotubes in nanomechanical mass sensing promises to further lower the detection limit to allow the measurement of single atomic masses.95 NEMS and similar approaches present an exciting prospect for single-cell metabolomics, peptidomics, and proteomics.96

The physical contact between the sampling apparatus and the cell is eliminated in laser ablation electrospray ionization (LAESI) MS. This ambient ionization method is also applied to single cell metabolomics. In LAESI, the native water content of cells efficiently absorb the energy of mid-infrared (mid-IR) light, which results in sample ablation.97 The ablated particulate matter is then captured into charged electrosprayed droplets to convert the chemical constituents of the sample into gas-phase ions that are subsequently detected by MS. In a recent embodiment of LAESI, a mid-IR light was passed through a sharpened optical fiber and a multidimensional video-microscopic system guided the fiber tip within ~30–40 μm of the selected plant cells (Fig. 5b).98 This variant of the LAESI technique provided single-cell resolution chemical imaging under native-like experimental conditions. As consecutive laser pulses were delivered, more than 300 distinctive ion signals were detected in situ from a single cell. Over 30 of these ions were assigned to different metabolites with the aid of tandem-MS experiments. LAESI-MS offers high throughput analysis by enabling populations of individual cells to be interrogated within a few minutes.

These MS-based approaches underscore the ability to identify key components of cellular chemistry by studying cells in an unbiased, discovery-oriented manner. With further enhancements in ionization such as the clathrate nanostructures or improved atmospheric ionization, the range and scale of these measurements will greatly increase.

Data analysis and interpretation

Approaches to interpret the data obtained are as varied as the approaches used to obtain the data and are covered in detail in the references to the individual highlighted approaches. The databases listed earlier containing metabolomics and peptidomics libraries are helpful in identifying the compounds detected by a variety of chemical information-rich analytical methods. Perhaps even more than metabolite characterization, peptide identification is aided by transcriptomic and genomic information. Nonetheless, the number of widespread posttranslational modifications of predicted gene products increases their biochemical complexity, which is dynamic and not encoded in genomes. Just as in genomics and transcriptomics, the role of bioinformatics and chemometrics in single cell metabolomics, especially in MS-based studies, is growing, with advances that integrate disparate data types being the key to future improvements.

Conclusions

The key structural and functional element of life on Earth is the cell. It has been intensively examined since the invention of the microscope in the 16th century. Today, new ‘omics strategies and approaches are targeting the chemical composition of individual cells, specifically, their DNA, RNA, proteins, and metabolites. As illustrated throughout this special issue, methodologies for single cell imaging, transcriptomics, and genomics have achieved a higher level of maturity than those for SCMP. While the SCMP technologies are potent in measuring subsets of the metabolome (e.g., lipids) or peptidome, they typically detect analytes present at the highest concentrations. There is no question that increases in sensitivity for MS and higher resolution separations will result in improved analyte coverage. Perhaps just as importantly, lossless sample preparation and more efficient analyte extraction will aid such studies.

While the analytical figures of merit required for single cell metabolome, peptidome and even proteome coverage are demanding, the rapid improvements in a wide range of technologies in bioanalytical microanalysis certainly suggests that more and more approaches will meet the requirements of SCMP measurements. We certainly expect that the next decade will showcase a wider range of SCMP methods that provide high throughput qualitative and quantitative analysis—with a greater depth of chemical coverage— to allow new applications in an increasing range of cell sciences (see Box 1 for examples).

Box1. New areas for bioanalytical microanalysis of single cells.

While many of the applications and research directions presented here relate to neuroscience and cancer biology, other areas will benefit from SCMP approaches. Stem cell research and developmental biology are two obvious disciplines that deal with single cell manipulation and analysis. Despite substantial progress over the last decade in understanding stem cell biology at the genomic and transcriptomic levels, much remains to be learned about changes in the metabolome and peptidome in order to advance stem cell application to replacement therapy (e.g., endocrine tissue) and individualized medicine. There is a need for detailed knowledge on the molecular properties of stem cells, their signaling regulatory pathways, and molecular mechanisms that drive proliferation and specialization of these cells into fully functional organotypic cells. To date, there have been numerous attempts to characterize these cells with gene-expression and proteomic studies on large cell populations using microarrays, antibody chips, peptide arrays, gel electrophoresis, and LC combined with MS. An emerging challenge that must be addressed is stem cell population heterogeneity, and this is where SCMP analysis at the single cell level would be invaluable. The current pace of technology development for sample collection, signal acquisition and data processing in a high-throughput manner will likely intensify in the coming decade.

Another avenue for SCMP research is the development of in vitro screening systems for toxicology and personalized medicine.99 Most toxicological studies rely on model organisms; translation of obtained results to the human is limited due to the obvious physiological interspecies differences. Likewise, tumor or in vitro transformed cell lines often lack the physiological properties of primary cells. Human stem cells, therefore, may serve as a unique and optimal model system for a well-controlled toxicity study maximally approximated to human physiology. For example, various organotypic somatic cells with normal physiological parameters characteristic of a specific cell type can be successfully obtained in the laboratory.100 However, heterogeneity of the cell populations limits the use of spontaneously differentiating multicellular aggregates, further emphasizing the need for screening assays performed at the single cell level. Induced pluripotent stem cells, commonly abbreviated as iPS cells or iPSCs, are a type of pluripotent stem cell artificially derived from a non-pluripotent cell, typically an adult somatic cell, by inducing a "forced" expression of specific genes.101 Presently, iPS cells are particularly interesting because not only can they be reprogrammed to develop into organotypic cells suitable for in vitro screening or for cell replacement therapies, they also have potential for personalized therapies and can be manipulated into individualized in vitro models of a particular human disease (see review by Okita et al.102). The use of human iPS cell lines from healthy and diseased donors for in vitro toxicological studies will be facilitated by screening methods that rely on the chemical analysis of single cells.

Just as in neuronal networks where individual cells have unique roles to play, during development individual cells can have unique roles in embryogenesis, apoptosis, regeneration, cell cycle and differentiation. These processes are highly dynamic and often associated with dramatic changes in the metabolome and peptidome of the cell of interest, as when progenitor cells differentiate into glutamatergic neurons, endocrine cells, and entire neuronal circuits. Three dimensional chemical imaging of metabolite distributions in individual Xenopus laevis oocytes81 by SIMS is a good example of the power of SCMP approaches when applied to developmental biology challenges, and we anticipate increasing interest in SCMP approaches by researchers in this field.

Given the rapid advancement of high throughput and high chemical information-rich characterization approaches, the future of SCMP will not only transform studies on cell-to-cell heterogeneity in stem cells, but also impact developmental biology, cancer and neuroscience-related research.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Award CHE-04-00768 from the National Science Foundation (NSF), and P30 DA018310, 5RO1NS031609, and 5RO1DE018866 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF or NIH.

References

- 1.Hausser M. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3 Suppl:1165. doi: 10.1038/81426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubel David H, Wiesel Torsten N. Brain and visual perception: the story of a 25-year collaboration. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goaillard JM, Taylor AL, Schulz DJ, et al. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:1424–1430. doi: 10.1038/nn.2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moroz LL, Gillette R, Sweedler JV. J. Exp. Biol. 1999;202:333–341. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brecht M, Schneider M, Sakmann B, et al. Nature. 2004;427:704–710. doi: 10.1038/nature02266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houweling AR, Brecht M. Nature. 2008;451:65–68. doi: 10.1038/nature06447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leong KG, Wang BE, Johnson L, et al. Nature. 2008;456:U804–U894. doi: 10.1038/nature07427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shackleton M, Vaillant F, Simpson KJ, et al. Nature. 2006;439:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nature04372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwab W. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:837–849. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmid A, Kortmann H, Dittrich PS, et al. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010;21:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmid G, Blanch HW. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1992;36:621–625. doi: 10.1007/BF00183239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao J, Yin XF, Fang ZL. Lab Chip. 2004;4:47–52. doi: 10.1039/b310552k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi B, Huang W, Cheng J. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:1595–1600. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garden RW, Shippy SA, Li L, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:3972–3977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen D, Dickerson JA, Whitmore CD, et al. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. (Palo Alto Calif) 2008;1:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kostal V, Arriaga EA. Electrophoresis. 2008;29:2578–2586. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang D, Bodovitz S. Trends Biotechnol. 2010;28:281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nery AA, Wrenger C, Ulrich H. J. Sep. Sci. 2009;32:1523–1530. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200800695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arruebo M, Valladares M, González-Fernández A. J. Nanomaterials. 2009;2009 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pruszak J, Sonntag KC, Aung MH, et al. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2257–2268. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumaier CE, Baio G, Ferrini S, et al. Tumori. 2008;94:226–233. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster PJ, Dunn EA, Karl KE, et al. Neoplasia. 2008;10:207–216. doi: 10.1593/neo.07937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conte-Perales L, Barroso-Chinea P, Rico AJ, et al. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raju DV, Smith Y. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2006 doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0114s37. Chapter 1, Unit 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neupert S, Gundel M. Peptides. 2007;28:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livet J, Weissman TA, Kang H, et al. Nature. 2007;450:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feng G, Mellor RH, Bernstein M, et al. Neuron. 2000;28:41–51. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huh Y, Oh MS, Leblanc P, et al. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2010;10:763–772. doi: 10.1517/14712591003796538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, et al. Cell. 2005;121:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young P, Qiu L, Wang D, et al. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:721–728. doi: 10.1038/nn.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Neupert S, Johard HAD, Nässel DR, et al. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:3690–3694. doi: 10.1021/ac062411p. The use of molecular labeling (here green fluorescent protein expression) facilitates the isolation of specific peptidergic neurons from the fruit fly brain for mass spectrometric analysis of neuropeptide products at the single cell level.

- 32.Rubakhin SS, Aldridge GM, Greenough WT, et al. Proceedings of the 56th ASMS Conference on Mass Spectrometry and Allied Topics; May 31–June 6, 2008; ASMS, Denver, CO. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guglielmi L, Battu S, Le Bert M, et al. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:1580–1585. doi: 10.1021/ac030218e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rapallino MV, Cupello A. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 2001;8:58–67. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(01)00088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Nature Protoc. 2007;2:1987–1997. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neupert S, Predel R. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;615:137–144. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-535-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bora A, Annangudi SP, Millet LJ, et al. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:4992–5003. doi: 10.1021/pr800394e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazzarello P. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999;1:E13–E15. doi: 10.1038/8964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle A, Griffiths JB. Cell and tissue culture for medical research. New York: Wiley, Chichester; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cunningham RE. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;588:319–326. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-324-0_31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krutzik PO, Nolan GP. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:361–368. doi: 10.1038/nmeth872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Voldman J. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006;17:532–537. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ateya DA, Erickson JS, Howell PB, Jr, et al. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;391:1485–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00216-007-1827-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotecha N, Flores NJ, Irish JM, et al. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandura DR, Baranov VI, Ornatsky OI, et al. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:6813–6822. doi: 10.1021/ac901049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown RB, Audet J. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2008;5 Suppl 2:S131–S138. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0009.focus. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClain MA, Culbertson CT, Jacobson SC, et al. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:5646–5655. doi: 10.1021/ac0346510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang D, Sims CE, Allbritton NL. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:2558–2565. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farzaneh Dehkordi F, Ahadi AM, Shirazi A, et al. J. Biol. Sci. 2009;9:78–82. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tyagi RK, Azrad A, Degani H, et al. Magn. Reson. Med. 1996;35:194–200. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ye X, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2008;168:373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Motta A, Paris D, Melck D. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:2405–2411. doi: 10.1021/ac9026934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reckel S, Hänsel R, Löhr F, et al. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2007;51:91–101. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee SC, Cho JH, Mietchen D, et al. Biophys. J. 2006;90:1797–1803. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Grant SC, Aiken NR, Plant HD, et al. Magn. Reson. Med. 2000;44:19–22. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200007)44:1<19::aid-mrm4>3.0.co;2-f. Further broadening the scope of NMR spectroscopy from entire living organisms, isolated organs, tissues, and even cultured assemblies of cells, here, perhaps for the first time, the technical feasibility of NMR spectroscopy is demonstrated for the spatial localization of osmolytes and metabolites in individual live neurons.

- 56.Olson Dean L, Peck Timothy L, Webb Andrew G, et al. Science. 1995;270 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maguire Y, Chuang IL, Zhang S, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:9198–9203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703001104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Krojanski HG, Lambert J, Gerikalan Y, et al. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:8668–8672. doi: 10.1021/ac801636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olson DL, Lacey ME, Sweedler JV. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:257A–264A. doi: 10.1021/ac9818071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amantonico A, Urban PL, Zenobi R. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3850-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Methods Mol. Biol. 2010;656:21–49. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-746-4_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kennedy Robert T, St Claire Robert L, White Jackie G, et al. Microchim. Acta. 1987;92:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kajiyama S, Harada K, Fukusaki E, et al. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2006;102:575–578. doi: 10.1263/jbb.102.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hsieh S, Dreisewerd K, van der Schors RC, et al. Anal. Chem. 1998;70:1847–1852. doi: 10.1021/ac9708295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mitruka BM, Alexander M. Appl. Microbiol. 1968;16:636–640. doi: 10.1128/am.16.4.636-640.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Iliffe TM, McAdoo DJ, Beyer CB, et al. J. Neurochem. 1977;28:1037–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Powell PR, Ewing AG. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2005;382:581–591. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3075-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Whitmore CD, Olsson U, Larsson EA, et al. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:3100–3104. doi: 10.1002/elps.200700202. Fluorescent microscopy is combined with capillary electrophoresis for the detection of fluorescently labeled products of cellular catabolism. With yoctomole detection levels, this method allows low level analytes to be measured in small individual cells.

- 69.Miao H, Rubakhin SS, Scanlan CR, et al. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:595–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fuller RR, Moroz LL, Gillette R, et al. Neuron. 1998;20:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hofstadler SA, Severs JC, Smith RD, et al. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 1996;10:919–922. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0231(19960610)10:8<919::AID-RCM597>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lapainis T, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:5858–5864. doi: 10.1021/ac900936g. A hyphenated capillary electrophoresis / electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry platform combines high-efficiency separations and confident identification of metabolites and neurotransmitters in single cells and subcellular structures.

- 73. Mellors JS, Jorabchi K, Smith LM, et al. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:967–973. doi: 10.1021/ac902218y. The described microfluidic device performs continuous on-chip cell lyses with real-time electrophoretic separation and mass spectrometric analysis of proteins in individual cells, characteristics well suited for SCMP.

- 74.Kraly JR, Holcomb RE, Guan Q, et al. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009;653:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jo K, Heien ML, Thompson LB, et al. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1454–1460. doi: 10.1039/b706940e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cheng W, Klauke N, Sedgwick H, et al. Lab Chip. 2006;6:1424–1431. doi: 10.1039/b608202e. A microelectrode device fully integrated within a microfluidic system is described that enables the real-time measurement of ionic and metabolic fluxes from individual electrically active, and beating heart cells in combination with simultaneous in-situ microscopy for optical measurements of cell contractility as well as fluorescence measurements of extracellular pH and cellular Ca2+.

- 77. Brouzes E, Medkova M, Savenelli N, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:14195–14200. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903542106. Using the example of human monocytic cell analyses, an integrated and robust microfluidic platform allows for the encapsulation of single cells and reagents in independent aqueous microdroplets (1 pL to 10 nL volumes) and enables the digital manipulation of these droplet reactors for the purpose of high-throughput single-cell analyses, combinatorial screening, and robust measurements form small samples.

- 78.Brehm-Stecher BF, Johnson EA. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2004;68:538–559. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.538-559.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu H, Volponi J, Oliver A, et al. Nature Precedings. 2010 < http://hdl.handle.net/10101/npre.2010.4428.1>. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kurczy ME, Piehowski PD, Van Bell CT, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:2751–2756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908101107. Secondary ion mass spectrometry imaging is used characterize lipid domains in single-cell organisms during mating; with this approach, localized composition changes in the plasma membrane of living cells is observed and shown to be related to local structure.

- 81. Fletcher JS, Lockyer NP, Vaidyanathan S, et al. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:2199–2206. doi: 10.1021/ac061370u. Using a breakthrough ion source technology, the third dimension is added to mass spectrometry imaging of small molecules from a cell. Analysis of lipids and lipid fatty acid side chains distribution as a function of depth enables three-dimensional images of an Xenopus laevis oocyte, thereby advancing the degree of biological complexity amendable to single cell metabolomics.

- 82.Monroe EB, Jurchen JC, Lee J, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12152–12153. doi: 10.1021/ja051223y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kaufmann R, Hillenkamp F, Nitsche R, et al. Microsc. Acta Suppl. 1978;2:297–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nordström A, Want E, Northen T, et al. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:421–429. doi: 10.1021/ac701982e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kruse RA, Rubakhin SS, Romanova EV, et al. J. Mass Spectrom. 2001;36:1317–1322. doi: 10.1002/jms.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Northen TR, Yanes O, Northen MT, et al. Nature. 2007;449:1033–1036. doi: 10.1038/nature06195. A new approach to high sensitivity spatially defined mass analysis that uses 'initiator' molecules trapped in nanostructured surfaces or 'clathrates' to release and ionize intact molecules adsorbed on the surface via ion or laser irradiation. Exciting demonstrations include peptide microarrays, direct mass analysis of single cells, tissue imaging, and direct chemical characterization of biological fluids.

- 87.Amantonico A, Urban PL, Fagerer SR, et al. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:7394–7400. doi: 10.1021/ac1015326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shimizu M, Levi-Schaffer F, Ojima N, et al. Anal. Sci. 2002;18:107–108. doi: 10.2116/analsci.18.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rubakhin SS, Garden RW, Fuller RR, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:172–175. doi: 10.1038/72622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. Anal. Chem. 2008;80:7128–7136. doi: 10.1021/ac8010389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bouschen W, Schulz O, Eikel D, et al. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2010;24:355–364. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4401. A nice optimization of the critical stages of sample preparation for MS-based chemical imaging of individual cultured human renal carcinoma cells with an impressive spatial resolution of 2 µm.

- 92.Cooks RG, Ouyang Z, Takats Z, et al. Science. 2006;311:1566–1570. doi: 10.1126/science.1119426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mizuno H, Tsuyama N, Harada T, et al. J. Mass Spectrom. 2008;43:1692–1700. doi: 10.1002/jms.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Naik AK, Hanay MS, Hiebert WK, et al. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009;4:445–450. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gil-Santos E, Ramos D, Martinez J, et al. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:641–645. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Doerr A. Nat. Methods. 2009;6:555. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Nemes P, Vertes A. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:8098–8106. doi: 10.1021/ac071181r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Shrestha B, Vertes A. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:8265–8271. doi: 10.1021/ac901525g. Laser ablation of single cells through a sharpened optical fiber is used for the detection of metabolites by laser ablation electrospray ionization (LAESI) mass spectrometry (MS), which allows the exploration of metabolic variations in cell populations.

- 99.Winkler J, Sotiriadou I, Chen S, et al. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:4814–4827. doi: 10.2174/092986709789909657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yamanaka S, Blau HM. Nature. 2010;465:704–712. doi: 10.1038/nature09229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Okita K, Yamanaka S. Exp. Cell Res. 2010;316:2565–2570. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]