Abstract

The definition of “genetic testing” is not a simple matter, and the term is often used with different meanings. The purpose of this work was the collection and analysis of European (and other) legislation and policy instruments regarding genetic testing, to scrutinise the definitions of genetic testing therewith contained the following: 60 legal documents were identified and examined—55 national and five international ones. Documents were analysed for the type (context) of testing and the material tested and compared by legal fields (privacy and confidentiality, data protection, biobanks, insurance and labour law, forensic medicine); some instruments are very complex and deal with various legal fields at the same time. There was no standard for the definitions used, and different approaches were identified (from wide general, to some very specific and technically based). Often, legal documents did not contain any definitions, and many did not distinguish between genetic testing and genetic information. Genetic testing was more often defined in non-binding legal documents than in binding ones. Definitions are core elements of legal documents, and their accuracy and harmonisation (particularly within a particular legal field) is critical, not to compromise their enforcement. We believe to have gathered now the evidence for adopting the much needed differentiation between (a) “clinical genetics testing”, (b) “genetics laboratory-based genetic testing” and (c) “genetic information”, as proposed before.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12687-012-0077-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Legislation, Definition, Genetic test, Genetic information, EuroGentest

Introduction

Definitions are key elements in law and their clarity is essential, as they define the scope of laws and the interpretation of its norms; absent, vague or improper definitions may, thus, impact on their applicability. Many laws and policy statements about genetic testing present different assumptions, concepts and terminology. The use of pragmatic, context-dependent definitions tends, on the other hand, to avoid ambiguity and clarify legal and technical terms. Thus, an important issue is whether, and to what extent, the definitions provided in legal instruments help achieving its anticipated aims.

Various normative approaches have been taken at the international, regional and national level to protect individual rights regarding the applications of genetic testing (Kosseim et al 2004). One study has pointed out some controversial definitions related to genetics, such as biological material or DNA, in legal documents (Gibbons 2007). That study examined how adequate the existing laws were, and how governance structures were applicable to genetic databases in England and Wales, and found significant differences between core concepts of genetic terms within four European countries (UK was compared with Estonia, Iceland and Sweden); the study identified different approaches to define genetic databases and their contents, e.g. biological material, DNA or other genetic samples, and genetic data.

An independent expert group assigned by the European Commission (EC) produced the “25 Recommendations on the Ethical, Legal and Social Implications of Genetic Testing” (European Commission 2004). This document established, as its very first recommendation, the need for “an explicit definition of the terms used” on any official statement or position but refers also the need to develop “a consensus definition of genetic testing”.

The expert group suggested also that this should be developed by “all respective public and private bodies involved (including the World Health Organisation, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the EC, the International Federation of Genetic Societies and the International Conference on Harmonisation)” and that “the EC should consider taking the initiative” on this topic.

As a consequence, the EC asked the FP6 Network of Excellence EuroGentest (www.eurogentest.org) to prepare such a definition (Sequeiros 2010). This led us to a review of definitions of genetic testing in documents (recommendations, guidelines, other) from several international and European institutions, professional organisations, regulatory bodies and agencies, national health institutions, pharmaceutical industry, insurers, ethical organisations, patient associations, human rights organisations and others (Sequeiros et al, in this issue).

A questionnaire was also sent to professionals dealing in any way with genetic testing about their own interpretation of these definitions and the proper use and its results published (Pinto-Basto et al. 2010). Another study concluded that the definitions contained in guidelines produced by professional and advisory bodies and international organisations were very inclusive and reflected a broad understanding of genetic data (Krajewska 2009).

With the present work, we have now extended this analysis and reflection to legal documents and other instruments intended for benchmarking when developing regulation from official bodies in the European Union (EU), EU Member States (MS) and other European countries, and included also some non-European countries (USA, Canada, Japan and Australia) for comparison. Our aims were to compare these legal documents among themselves and relate them to the context for which they had been presented, as well as to their specific aims and purposes.

The ultimate goal of this work was to assess further the possibility of attaining a consensus definition and to provide evidence for the need to adopt, when regulating genetic testing, the methodology and definitions framework proposed before (Sequeiros 2010).

In that previous work, we have suggested (1) the need to categorise beforehand the items to be included/excluded (scope); (2) a decision-tree considering both the context, and the methods and material used for genetic testing; and (3) a scaffold of context-dependent definitions, which included the concepts of “clinical genetics testing”, “genetics laboratory-based genetic testing” and “genetic information” (Sequeiros 2010).

Methods

Definitions and concepts

By the expression “legal document” we mean all documents that were, directly or indirectly, created by an authorised state (public) organisation: the author may be either a governmental body, council or working group nominated by it. A “legal document”, as defined here, can be any type of legal norm, including laws emanating from a government or parliament, but also regulation, resolutions, conventions, etc. This term was chosen to encompass not only both (national and international) legislation (hard law) but also some soft law (as the recommendations from international/transnational institutions and the guidelines from professional organisations, etc.) that were relevant to the field of genetic testing. For the purposes of this study, the term legal documents (also used here as legal tools or legal instruments) does not include other concrete legal documents (such as, e.g. court orders).

The so-called “hard law”, means binding laws and decrees, passed by a competent legislator body, such as a national or the European parliament, or a national Government or Ministry. Hard law is linked to an enforcement system and legal consequences, in case the law is breached. In addition to hard law, there are guidelines, standards and recommendations, which set operational principles or recommendations for activities in a given field. These instruments are usually described as “soft law”, even though there are controversial perceptions about the notion of soft law, and its impact (Trubeck et al. 2005). They are often based on negotiations between different stakeholders and, thus, reflect commonly accepted minimum ethical criteria intended to set basic standards. Soft law instruments may also be the outcome of professional self-regulation. The Helsinki Declaration is the most notorious example, even though it has now been institutionalised, due to a reference in the EC Clinical Trials Directive (2001/20/EC).

In addition, the Oviedo Convention is a good example of how some soft laws may become enforceable; though the Council of Europe cannot issue binding legal instruments, once its recommendations are approved by the Council of Ministers, signed and ratified by the Member countries, those will be transposed into national laws and thus becomes hard law.

Legal documents from EU Institutions (EU law) and the Council of Europe (CoE) (international law) have already been analysed (Sequeiros et al, in this issue) and are used here again, together with the “Additional Protocol…” (Council of Europe 2008) to the Oviedo Convention (Council of Europe 1997), only to provide a comparison with national laws (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of genetic testing and their documents

| European Union (EU27) Institutions and Council of Europe (CoE) | ||

| EC | Opinion of the Group of Advisers on the Ethical Implications of Biotechnology to the European Commission | ✓ |

| EC | Opinion on the Ethical Aspects of Genetic Testing in the Workplace (Opinion No. 18) | ✓ |

| CoE | Recommendation No. R (92) 3 on Genetic Testing and Screening for Health Care Purposes (Feb. 10, 1992) | ✓ |

| CoE | Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being (Oviedo, 1997) | ✓ |

| CoE | Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine Concerning Genetic Testing for Health Purposes (CETS No. 203) | ✓ |

| European Union (EU27) Member States | ||

| Austria | Austrian Gene Technology Act | ✓ |

| Austria | Book of Gene Technology | ○ |

| Belgium | Genetics and Insurance | ○ |

| Belgium | Royal Decree | ✓ |

| Belgium | Act on Medically Assisted Procreation and the Disposition of Supernumerary Embryos and Gametes, of 6 July 2007 | ○ |

| Bulgaria | Bulgarian Health Act | ✓ |

| Cyprus | The Safeguarding and Protection of Patients’ Rights Law, 2004 | ✓ |

| Czech Republic | – | ■ |

| Denmark | Health Act No. 546, of 24 June 2005 | ✓ |

| Denmark | Law on Artificial Fertilization in Connection with Medical Treatment, Diagnosis, and Research (Research on Embryonic Stem Cells) | ✓ |

| Denmark | Act on the Use of Health Data…on the Labour Market | ✓ |

| Estonia | Human Genes Research Act | ✓ |

| Finland | Act on the Protection of Privacy in Working Life | ✓ |

| France | Penal Code | ✓ |

| France | Decree No. 2008-321, of 4 April 2008, on the Examination of the of Genetic Characteristics of a Person and the Identification of that Person by Genetic Fingerprints for Medical Purposes | ○ |

| France | Criminal Procedure | ✓ |

| Germany | Predictive Health Information in the Conclusion of Insurance Contracts | ✓ |

| Germany | Law and Ethics in Modern Medicine | ✓ |

| Germany | Genetic Diagnosis Before and During Pregnancy | ✓ |

| Germany | Genetic Diagnosis Act—GenDG | ✓ |

| Greece | Code of Medical Ethics | ○ |

| Greece | Opinion on Prenatal and Pre-Implantation Diagnosis | ✓ |

| Greece | Recommendation on the Collection and Use of Genetic Data | ✓ |

| Hungary | Health Care Act | ✓ |

| Hungary | Proposal to the Government on the Draft Bill on the Protection of Human Genetic Data and the Rules for Genetic Tests and Research | ✓ |

| Ireland | A Guide to Ethical Conduct and Behaviour (6th edition) | ✓ |

| Ireland | Disability Act 2005 | ✓ |

| Italy | Bioethical Guidelines For Genetic Testing | ✓ |

| Latvia | Human Genome Research Law | ✓ |

| Lithuania | – | ■ |

| Luxemburg | – | ■ |

| Malta | – | ■ |

| Poland | – | ■ |

| Portugal | Personal Genetic Information and Health Information (Law 12/2005, of 26 January) | ✓ |

| Romania | – | ■ |

| Slovakia | ACT on the Application of Deoxyribonucleic Acid for the Identification of Persons | ✓ |

| Slovenia | – | ■ |

| Spain | Law on Biomedical Research | ○ |

| Sweden | Act on Genetic Integrity | ✓ |

| Sweden | Ordinance No. 358, of 18 May 2006, on Genetic Integrity | ○ |

| Sweden | Biobanks in Medical Care Act | ✓ |

| The Netherlands | Policy Document: The Application of Genetics in the Health Care Sector | ✓ |

| UK | Human Tissue and Embryos Bill | ✓ |

| UK | Code of Practice and Guidance on Human Genetic Testing Services Supplied Direct to the Public | ✓ |

| UK | Discrimination Law Review. A Framework for Fairness: Proposals for a Single Equality Bill for Great Britain | ✓ |

| UK | Concordat and Moratorium on Genetics and Insurance | ✓ |

| UK | Draft Code of Practice: The use of Personal Data in Employer/Employee Relationships | ✓ |

| UK | Our Inheritance, Our Future: Realising the Potential of Genetics in the NHS | ✓ |

| UK | Code of Practice and Guidance with Respect to Genetic Paternity Testing Services | ✓ |

| UK | Laboratory Services for Genetics | ✓ |

| UK | ||

| (Northern Ireland) | The Human Organ Transplants (Establishment of Relationship) Regulations Statutory Rule, 1998 | ✓ |

| UK | Human Tissue Act, 2004 | ✓ |

| Other (Non-EU) European Countries | ||

| Albania | – | ■ |

| Belarus | - | ■ |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina | – | ■ |

| Croatia | – | ■ |

| Georgia | Law of Georgia, of 5 May 2000, on the Rights of Patients | ✓ |

| Iceland | Regulations on the Keeping and Utilisation of Biological Samples in Biobanks | ✓ |

| Lichtenstein | – | ■ |

| Macedonia | – | ■ |

| Moldova | – | ■ |

| Monaco | – | ■ |

| Norway | Act No. 100, of 5 December 2003, Relating to the Application of Biotechnology in Human Medicine… | ✓ |

| Norway | The Medical Use of Biotechnology | ✓ |

| Russia | – | ■ |

| Serbia | – | ■ |

| San Marino | – | ■ |

| Switzerland | Ordinance of 31 May 2000, on the Information System Based on DNA Profiles (Ordinance on DNA) | ✓ |

| Switzerland | Swiss Federal Law on Human Genetic Analysis, 2004 | ✓ |

| Turkey | – | ■ |

| Ukraine | – | ■ |

| Non-European Countries | ||

| Australia | Genetic Testing—Guidelines for Prioritising Genetic Tests | ✓ |

| Australia | Ethical Guidelines on the Use of Assisted Reproductive Technology in Clinical Practice and Research (as revised in 2007 to take into account the changes in legislation) | ✓ |

| Australia | Genetic Testing and Storage of Genetic Material/Information | ✓ |

| Australia | ALRC 96, Essentially Yours: The Protection of Human Genetic Information in Australia (this report reflects the law, as at 14 March 2003) | ✓ |

| Canada | Genetic Testing and Privacy | ✓ |

| Canada | CCMG Molecular Genetics Guidelines | ✓ |

| Japan | Guidelines For Genetic Testing | ✓ |

| Japan | Guidelines for Genetic Testing, Using DNA Analysis | ✓ |

| USA | Executive Order, To Prohibit Discrimination in Federal Employment Based on Genetic Information | ✓ |

| USA | Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act of 2008 | ✓ |

| USA | Genomics and Personalized Medicine Act of 2007 (Introduced in Senate) | ✓ |

Definitions or relevant text describing “genetic testing” in these legal documents and its URLs are provided as Supplementary Material

(✓) definitions found and analysed, (○) no definitions included or no translation available, (■) no legal documents found

International rules usually need to be incorporated into national law to become applicable. Thus, regulatory instruments such as the Oviedo Convention become legally binding only after national transposing measures. The situation is different, however, with EU law, as Member States are obliged to transpose EU Directives into their national legislation and because EU Regulation is directly binding.

Other, non-legal, non-binding norms and codes (as professional and other guidelines and recommendations), reviewed before (Sequeiros et al, in this issue), were not included in this analysis.

Legal databases and other resources

This study was based primarily on the legal documents found searching various online resources, between 2008 and 2011. Legal databases (specialised on genetics and a general one) were systematically used to collect national legislation and policy documents concerning genetic testing. Two are kept by the World Health Organisation (WHO): (1) the Ethical, Legal, Social Implications & Issues of Human Genome Project Genetics Resource Directory (WHO 2008a), which aims “to provide ready access to existing legislation and policy documents relating to various aspects of genetic research and applications” and (2) the International Digest of Health Legislation (WHO 2008b), which contains a selection of national and international health legislation relating to health care, in every member state of WHO. (3) The HumGen database (HumGen International 2008) concerns ethical, legal and social issues in human genetics. (4) The Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine (Central European University 2005) has also established a database on law, ethics and policy in the field of biomedical law, including human genetics. (5) The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development database (OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry 2008), (6) the EuroGentest database on “Regulations and Practices Related to Genetic Counselling in 38 European Countries” (Rantanen et al. 2008) and (7) the “European Ethical-Legal Papers” series (WP6.4 of EuroGentest 2008; www.eurogentest.org) are all based on surveys and, thus, better refined and analysed than simple data collections. (8) A well-known general legal database, Lexadin (2008), which includes laws and norms on health care, insurance, labour, private law, etc., was also used. Finally, (9) national legal databases were also searched whenever there were no language barriers or technical problems.

The CoE, EU institutions, the EU27 MS, other (non-EU) European countries, as well as Australia, Canada, Japan and USA, were all surveyed for legal documents and policy instruments available in English (even if only in an unofficial translation) containing any definition of genetic testing.

Analysis and software

All the online resources were searched for international and national legal documents, using keywords, such as genetic testing and genetic test(s), as well as specific types of tests/testing and sources of genetic information (including related synonyms): diagnostic (genetic) test, confirmation/confirmatory test, genetic diagnosis, presymptomatic test, predictive test, carrier test, heterozygote/heterozygosity test, disease predisposition test, susceptibility test, test for complex diseases, drug response test, pharmacogenetics test, adverse drug reactions, drug dose adjustment, prenatal test, f(o)etal testing, preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), pre(-)implantation diagnosis, population (genetic) screening, identity (genetic) testing, forensic testing, civil identification, criminal identification, paternity testing, family testing, twin/zigosity testing, chromosome(ic)(al) analysis, cytogenetic, karyotype, genes, nucleic acid, genetic (material), DNA, gene products, biochemical test, genetic biochemistry, metabolic test, protein, hormone, enzyme activity, RNA, metabolites, routine blood tests, clinical pathology, blood test (exams) (workup), family history (information) (tree), pedigree (information), genogram and genealogy/genealogical.

These documents were all analysed with NVivo8 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster Victoria, Australia), a software for the analysis of text data. Documents were classified by legal fields (Table 2) and for the same items (type of testing, object of test, etc.) as used before (Sequeiros et al, in this issue) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the definitions of genetic testing in different legal fields (scope)

| Legal Field | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main features | Labour and/or insurance law | Privacy and confidentiality/data protection and law on biobanks | Health care law | Forensics (criminal/civil) and family law | Complex laws |

| Specificities | Specific genetic mutations and susceptibilities, incl. exposure to work environment or increased future disease risk, stratification of risks and actuarial activity | Protection of patient and human rights, non-disclosure of genetic information without informed consent | Diagnosis, treatment, prevention, genetic counselling, quality assurance, population screening, clinical research or research applied to human disease | Civil and criminal identification, identify human bodies/remains, parenthood or kinship | Various and very general |

| Explicit exclusions | Potential danger to others or public health | Reporting results from research biobanks without prior consent/policy | Research without informed consent in diagnostic samples | Use of potentially diagnostic information | Various |

| Target group of genetic testing | Employees and candidates to employment or life/health insurance | Human volunteers, general population | Affected patients, persons at risk, population at large | Suspected or actual criminal offenders, convicts, missing persons, general population, disputed paternity | Health related |

| Example | USA: Executive Order to Prohibit Discrimination in Federal Employment Based on Genetic Information | Portugal: Personal Genetic Information and Health Information Law | Australia: Genetic Testing—Guidelines for Prioritizing Genetic Tests | Slovakia: Act on the Application of DNA for the Identification of Persons | CoE: “Oviedo Convention” and Additional Protocol Concerning Genetic Testing Related to Health |

Table 3.

Items covered by the various definitions of genetic testing contained in legislation

| COUNTRY Legislation | Legal field (scope) | Type of testing (context) | Object (material/method) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Labour/insurance law | Privacy, confidentiality and biobanks law | Health care law | Forensic/criminal/civil identification/family law | Complex | Diagnostic testing | Presymptomatic testing | Disease predisposition testing | Drug response | Carrier testing | Prenatal testing | PGD | Population screening | Identity testing | Chromosomes | DNA | Specific gene products | Routine blood tests | Family history | |

| EU + CoE | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Opinion No. 18” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| “Recommendation No. R (92) 3” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| “CDBI-CO-GT4” | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| “Oviedo Convention” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| “Additional Protocol” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| Austria | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Austrian Gene Technology Act” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| Belgium | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Royal Decree” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Bulgaria | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Bulgarian Health Act” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Cyprus | |||||||||||||||||||

| “The Safeguarding …” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Demark | |||||||||||||||||||

| “… on patients’ rights” | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| “Law on artificial fertilization…” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| “Act on the use of health data …” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Estonia | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Human Genes Research Act” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Finland | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Privacy in Working Life” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| France | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Code Penal” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| “Criminal Procedure” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| Germany | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Predictive Health Information …” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| “Second Interim Report” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| “Genetic diagnosis …” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||

| “GenDG” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Greece | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Opinion on Prenatal …” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| “Use of Genetic Data” | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| Hungary | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Health Care Act” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| “Proposal to the Government…” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Ireland | |||||||||||||||||||

| “A Guide to Ethical Conduct …” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| “Disability Act 2005” | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| Italy | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Bioethical guidelines …” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||

| Latvia | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Human Genome Research Law” | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| Northern Ireland | |||||||||||||||||||

| “The Human Organ Transplants” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| Portugal | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Personal genetic information” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| Slovakia | |||||||||||||||||||

| “…identification of persons” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| Sweden | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Act on Genetic Integrity” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| “Biobanks in Medical Care Act” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| The Netherlands | |||||||||||||||||||

| “The application of Genetics …” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| UK | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Human Tissue and Embryos Bill” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||

| “Code of practice …” | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| “Discrimination Law Review …” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| “Concordat and Moratorium …” | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| “The use of Personal Data …” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| “Our Inheritance, Our Future” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| “… genetic paternity testing” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| “Laboratory Services for Genetics” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| “Human Tissue Act 2004” | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| Australia | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Guidelines for prioritising…” | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| “Ethical guidelines…” | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| “Genetic testing and storage…” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||

| “ALRC 96” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||

| Canada | |||||||||||||||||||

| “CCMG Mol.Gen. Guidelines” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||

| Georgia | |||||||||||||||||||

| “on the Rights of Patients” | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| Iceland | |||||||||||||||||||

| “… biological samples in biobanks” | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||

| Japan | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Guidelines for genetic testing” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| “… using DNA analysis” | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||

| Norway | |||||||||||||||||||

| “… biotechnology in human medicine” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| “The medical use of biotechnology” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| Switzerland | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Ordinance on DNA” | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| “Human Genetic Testing—Federal Law” | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||

| United States | |||||||||||||||||||

| “Executive Order …” | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||

| “… Non-discrimination Act of 2008” | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

| “Genomics and Personalized …” | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||

(+) ‘legal field’ touched by each document (scope) and whether a given term or phrase was used in it (context and material/method covered)

Results

Countries and legal documents

The countries surveyed and legal documents identified are shown in Table 1. No relevant legislation was found for Albania, Belarus, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Monaco, Poland, Romania, Russia, San Marino, Serbia, Slovenia, Turkey and Ukraine.

A total of 67 documents were identified: 62 national (from 48 countries—44 European and four non-European countries) and five international documents (from the EC and CoE). Their availability in English allowed the analysis of 60 of these: 55 national and five international; one document from Canada (“Genetic testing and privacy”), however, was not importable into NVivo 8. For the legal documents found for Belgium, France, Greece, Spain and Sweden, either no definitions of genetic testing were found or no English (official or unofficial) translation was available. The weblinks for the documents used, as well as definitions or the relevant text they contain, are available as “Supplementary Data”, as well as on the EuroGentest website (Varga and Sequeiros 2008).

Legal fields and items covered

Most of the documents found related to (1) labour, (2) insurance, (3) biobanks, (4) data protection, (5) health care or regulation of medical activity, (6) forensic/criminal genetics, (7) family, (8) privacy/confidentiality and (9) international law. Definitions of genetic testing applying to different fields were analysed, and their main features are summarised in Table 2. Since legal fields often overlap in a single document, more than one legal field may have been identified for each one (Table 3). This multiple marking may also have helped reducing biases in the analysis.

Table 3 is organised into (1) “legal fields”, which refer to the scope of the documents (as some fields overlap, those were grouped together for discussion), (2) “type of testing”, referring to the context of application of the genetic test and (3) “object”, which pertains to the type of “material” used for a genetic test (in its broader sense of any source providing genetic information).

Binding vs. non-binding legal instruments

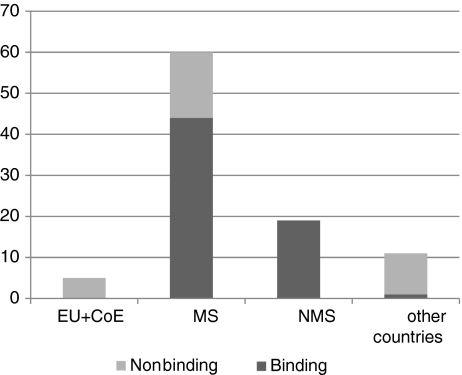

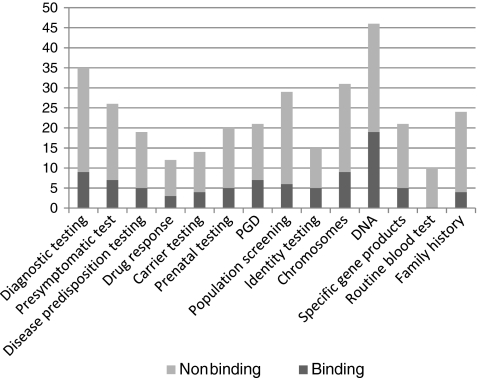

Documents were also compared as to their binding effect. The proportion of binding to non-binding, among international and national documents (EU27 MS and non-EU countries), is shown in Fig. 1. European MS issue more binding than non-binding legal documents (58% vs. 42%). Figure 2 shows the cumulative number of (binding and non-binding) documents, by type (context) and object (material) of genetic testing. DNA (or synonyms) was the most frequent item in these documents. Interestingly, all terms related to genetic testing were more frequent in non-binding than in binding legal documents.

Fig. 1.

Number of legal documents regarding genetic testing in different types of documents (the relevant text and the URLs for the documents can be found as Supplementary Material). EU + CoE European Union (EU) and the Council of Europe (CoE), MS Member States of the EU27, NMS other (non-EU) European countries, Other countries other, non-European, countries

Fig. 2.

Cumulative number of binding and non-binding legal documents, by type and object of genetic testing (only the main term is indicated, though it includes its respective synonyms/related terms found). For each item, only the main term is indicated, although the search was conducted with various synonyms as well

Discussion

The importance of clear definitions when regulating genetic testing

Genetic testing can affect many aspects of life, including education, profession, employment, insurance, forensics, ancestry, basic and applied research, health care, etc. One of the biggest challenges is to find the proper focus for specific legislation and regulation of genetic testing.

It is, thus, essential to use clear, context-dependent definitions when regulating genetic testing. In a previous publication, we stress the need to (1) precise the scope of each legal instrument (e.g. it is fundamental to separate human from non-human, and medical from non-medical applications), (2) to explicit the methods and genetic material used for genetic testing, (3) to consider the context for clinical applications (distinguishing diagnostic testing, i.e. to confirm/exclude a medical diagnosis, from the various forms of predictive testing performed in healthy persons), (4) to use in its proper sense well-defined terms (such as cascade testing and population genetic screening, PGD and preimplantation genetic screening or the distinguish the predictive value of testing in various forms of cancer), (5) to be aware of the controversial use of some terms (such as presymptomatic and predictive testing, screening, carrier), (6) to distinguish among genetics laboratory-based tests, clinical genetics testing and genetic information and (7) all of these according to the aims and purposes of the legal instrument (Sequeiros 2010).

Legal fields and scope of definitions

A “legal field” is a rank in the vertical structure of the legal system. Each field relates to laws or legal norms and specific principles that are more or less connected because of their similar topic, the issues they regulate or their legal demands. This concept may help understanding and reaching more transparent and effective legislation and regulation.

In the legal documents analysed in this work, the distinction we made between the various fields was necessarily arbitrary (Table 2), since those documents frequently touched several legal fields at the same time. In theory, a distinction can be made among insurance/labour, privacy/confidentiality and data protection laws, based upon their target groups and the purpose of genetic testing; in practice, however, these fields are intimately connected, and it is difficult to treat them separately. Most definitions of genetic testing emphasised issues related to health care and privacy/confidentiality; a possible reason for this mixed classification is the importance of privacy and confidentiality of genetic information in relation to other legal fields. A relatively small number of documents were found within the scope of civil/criminal identification or of insurance/labour law (Table 3).

Legal fields and applications of genetic testing

When comparing definitions contained in various legal documents, as to its purposes, there were three major broad applications of genetic testing: (1) identification (including, e.g. forensics, civil or criminal and family law), (2) health care and medical research (including, e.g. medical care, laboratory quality assurance, patient rights) and (3) data protection and antidiscrimination (including, e.g. insurance, employment, data protection, privacy and confidentiality, biobanks, human rights).These are explained as follows:

Identification: the definitions of genetic testing contained in the legal documents addressing mainly identity testing are often more restrictive. Although forensic genetic testing is also based on the direct investigation of DNA, it usually targets non-coding sequences, for (civil or criminal) identification of a single person, rather than testing a specific gene or mutation, as is still the main practice in medical genetics testing.

Medical applications: these documents often provided complex definitions, using sometimes coded professional language, and distinguishing among several subtypes of genetic tests, for population genetic screening, diagnosis, counselling, prevention or treatment of a particular hereditary disease or one with a genetic component.

Data protection and anti-discrimination: these documents contained usually general definitions. In the specific context of labour and insurance law, definitions aim at well-defined groups, while in the case of privacy and confidentiality law, they are much broader (usually emphasising that genetic tests should serve mainly or merely medical purposes and not be used to violate basic human rights or human dignity).

It is important to note that most EU27 MS have not yet developed legislation or other legal norms relating specifically to genetic testing (see Table 1). One explanation for this gap may be a lack of understanding of the specificities of genetic testing (particularly in healthy persons), and its familial, ethical and social implications; another may be a view opposing genetic exceptionalism, deliberately leaving genetic testing to be covered under general health care regulation.

Very often, there were no general definitions contained, or the legal document failed to provide a specific definition of genetic testing. One such example is the Hungarian Health Care Act (1997:CLIV.tv), which does not provide a definition or clarify what it means by a genetic test, although it regulates how genetic testing and counselling should be performed in health care.

Legally binding and non-binding documents

We could not find any binding documents issued by the EU institutions or the Council of Europe containing definitions of genetic testing (Fig. 1). This is not surprising, since these entities have no or only restricted power to issue binding laws for the MS, in the field of genetics. The EU27 MS themselves, as other non-EU European countries, seem to issue more binding than non-binding legal documents containing definitions of genetic testing, while the trend in the non-European countries surveyed is the opposite.

Examining the components of these definitions (Fig. 2), we found that the most frequently occurring term/phrase (either alone or part of definitions) was DNA (or a synonym). Definitions of genetic testing occurred much more frequently in non-binding legal documents.

Structure of definitions: general and specific approaches

The different complexity of the definitions can be identified in terms of their structure: some use a general definition (based only on technical terms such as DNA), while others apply a more specific one. Although the technical (laboratory) description of genetic testing should be distinguished from that of genetic information, this difference was rarely made in the legal documents analysed. One of the examples for such a clear distinction is the Portuguese law on “Personal Genetic Information and Health Information” (Law no. 12/2005).

The more “general definitions” do not provide a precise description of the purpose and target group but apply a broad approach, often unclear from a medical or scientific point of view. Two types of general definitions could be found among the documents examined:

Some general definitions of “genetic testing” are based on a technical description of medical/scientific terms, as DNA, genes, etc. As an example, the Australian “Ethical Guidelines on the Use of Assisted Reproductive Technology in Clinical Practice and Research (as revised in 2007 to take into account the changes in legislation)” states: “A genetic test is one that reveals genetic information. It may be performed on DNA, RNA or protein (the ‘gene product’), or involve measurement of a substance that indirectly reflects gene function.”

Other general definitions list different subtypes of genetic testing, with the respective technical terms. This is the case with the Hungarian “Proposal to the Government on the Draft Bill on the Protection of Human Genetic Data and the Rules for Genetic Tests and Research”: It mentions that a genetic test is “a laboratory test aimed at disclosing DNA and/or chromosome variations and their specific protein products, which are accompanied by or predict effects that have an adverse influence of human health. Types of genetic test include diagnostic, presymptomatic, predictive, heterozygote and prenatal tests. Genetic screening is a wide-range programmed genetic test provided to a population or a group of population for the purpose of identifying certain genetic characteristics in asymptomatic persons, thereafter called collectively as ‘genetic testing’)”.

The other main approach is giving specific definitions of genetic testing, highlighting their purpose and target group, not the source of the genetic information. The British document on “The Use of Personal Data in Employer/Employee Relationships” declares that “employers should not require employees to undergo genetic testing (or other tests identifying susceptibility to disease) unless it can be objectively justified on either strong public, or employee, health and safety grounds. Such tests may only be carried out with the prior consent of the employee concerned and if the results are interpreted by a qualified health professional who has completed higher specialist training in clinical genetics under the Royal College of Physicians, or an equivalent overseas body”.

The Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (Oviedo Convention) and its Additional Protocol Concerning Genetic Testing for Health Purposes

The Oviedo Convention and its Additional Protocol deserve special mention, since they had a crucial role in benchmarking human rights in biomedicine, including issues on genetic testing and counselling. The “Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (CETS No. 164)”, also known as the Oviedo Convention, has been ratified, so far, by 28 European countries1: Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Montenegro, Norway, Portugal, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, the F.Y.R Macedonia and Turkey.

Article 12 of the Convention focuses on predictive genetic tests and states that “tests which are predictive of genetic diseases or which serve either to identify the subject as a carrier of a gene responsible for a disease or to detect a genetic predisposition or susceptibility to a disease may be performed only for health purposes or for scientific research linked to health purposes, and subject to appropriate genetic counselling.”

In April 2008, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe adopted the “Additional Protocol” to the Convention “Concerning Genetic Testing for Health Purposes” (Council of Europe 2008). It sets down principles relating to the quality of genetic services, prior information and consent, genetic counselling and population screening, and uses the concepts of clinical validity and utility of genetic tests. It is the first international instrument with intended legal effects concerning genetic testing for health purposes (Lwoff 2009).

The Explanatory Report to this Additional Protocol (Article 2 26.) declares that it applies to tests carried out for health purposes, which involve analysis of biological samples of human origin, and specifically aim to identify genetic characteristics of a person that are inherited or acquired during early prenatal development. The notion of “genetic test” in the Explanatory Report (Article 2 29.) is based both on the method used and the purpose of the test. It is to be understood as a procedure including the removal of biological material of human origin, as well as the analysis of the personal information obtained from it. It refers to chromosomal analysis, DNA or RNA analysis, or analysis of any other element enabling information that is equivalent to that obtained by the first two methods (Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe 1996).

Limitations of the study

The purpose of this paper was the collection and analysis of legal documents and other policy-making instruments and the comparison of the definitions of genetic testing they contained. There were, however, some study limitations with respect to the sources and the analysis.

Language

A significant proportion of national legislation and norms was not available in English (neither in official or unofficial translation); therefore, we decided to exclude them, as we lacked the resources to translate them all. We must also bear in mind that unofficial translations may not be fully faithful to the original sense (readers may find the relevant translated parts as Supplementary Material).

Availability

A general legal database, which includes all the legislation of all European countries and of the European Institutions, does not yet exist. Most legal databases relating to genetics focus on legislation from the EU MS.

Differences in legal systems

Differences between continental European and common law (as in the UK) are evident and may complicate comparison of legal documents.

Conclusions

Clear and precise definitions in national, international and supranational law are very important, since they may determine the applicability of the legislation and affect its enforcement. Our results, however, showed that many legal documents do not have any definition at all or a clear definition of genetic testing.

Regulation of genetic testing varies from country to country and is heavily dependent on the type of legal document (binding or non-binding) and their final purposes. A definition of genetic testing was more frequent in binding legal documents, than in non-binding ones, mainly in the EU27 MS, but also in other European countries.

Main legal fields included insurance and labour; privacy, confidentiality and data protection; biobanks; health care; and identity testing. Most laws, however, were not specific and related to several legal fields at the same time. This is the case mainly with international or transnational soft law.

While most legal documents dealing with health care and privacy/confidentiality contained definitions of genetic testing, only a small number of those on forensic testing and insurance/labour law did.

Some definitions are provided on a technical basis, or on a list of specific types of genetic testing, while others are more detailed and refer a precise target group or the purpose they are meant to cover. Most documents relating to health care and/or privacy and confidentiality contain definitions of genetic testing that are technically driven, while definitions in insurance and labour law tend to be more descriptive.

Many legal documents do not show full awareness of what the term genetic testing may encompass. Thus, the legislator (in different countries) often has not helped to solve the issues for which the law or policy document was intended. If the law is trespassed, the actual formulation of those instruments may create difficult problems, open to different interpretations.

When present, definitions were extremely variable and often unclear and imprecise. Creating a definition that fits the aims of a legal document requires some effort from the legislator, so that not just the scope but also the context and the material and methods to be covered are clearly specified.

Clear operational definitions according to the scope of each legal document, that are both scientifically and legally sound, or, preferably, the use of well-informed, context-dependent definitions, will help avoiding ambiguity and creating new problems, in case the law is breeched.

Harmonisation of definitions may be very challenging, but it is also very much needed within the various legal fields, and according to the context of application of genetic tests.

We believe the present study has now provided the evidence needed for the adoption of separate definitions for (a) “clinical genetics testing”, (b) “genetics laboratory-based genetic testing” and (c) “genetic information”, as proposed before (Sequeiros 2010). A framework of clear, context-dependent, definitions should help developing legislation and regulation of “genetic testing” that proves to be coherent and enforceable.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 88 kb)

Footnotes

For a timely list of ratifications, see: http://conventions.coe.int/Treaty/Commun/ChercheSig.asp?NT=164&CM=8&DF=24/08/2011&CL=ENG and http://www.coe.int/bioethics

References

- Central European University (2005) Center for Ethics and Law in Biomedicine. http://web.ceu.hu/celab/. Accessed 31 December 2008

- Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe (1996) Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, Explanatory Report. DIR/JUR (97) 5. Secretary General of the Council of Europe, Strasbourg

- Council of Europe (1997) Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, Oviedo, 4.IV.1997. ETS No. 164. Oviedo

- Council of Europe (2008) Additional Protocol to the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, Concerning Genetic Testing for Health Purposes. No. 203 Council of Europe Treaty Series ed, Strasbourg [PubMed]

- EuroGentest (2008) European Ethical & Legal Papers, no. 1–16. WP6.4 of EuroGentest. http://www.eurogentest.org/patient/ethical_and_legal. Accessed on 29 December 2011

- European Commission (2004) 25 Recommendations on the Ethical, Legal and Social Implications of Genetic Testing. Directorate-General for Research, Brussels. ISBN 92-894-7308-8

- Gibbons SM. Are UK genetic databases governed adequately? A comparative legal analysis. Leg Stud. 2007;27(2):312–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-121X.2007.00045.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- HumGen Database of Laws and Policies (2008) http://www.humgen.umontreal.ca/int/search.cfm?mod=1&lang=1. Accessed 31 December 2008

- Kosseim P, Letendre M, Knoppers BM. Protecting genetic information: a comparison of normative approaches. GenEdit. 2004;2(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Krajewska A. Conceptual quandaries about genetic data—a comparative perspective. Eur J Health Law. 2009;16(1):7–26. doi: 10.1163/157180909X400204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lexadin: The World Law Guide (2008) http://www.lexadin.nl/wlg/legis/nofr/legis.htm. Accessed 31 December 2008

- Lwoff L. Council of Europe adopts Protocol on Genetic Testing for Health Purposes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(11):1374–1377. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD Directorate for Science, Technology and Industry (2008); http://www.oecd.org/infobycountry/0,3380,en_2649_34537_1_1_1_1_1,00.html. Accessed 31 December 2008.

- Pinto-Basto J, Guimarães B, Rantanen E, Javaher P, Nippert I, Cassiman JJ, Kääriäinen H, Kristoffersson U, Schmidtke J, Sequeiros J. Scope of definitions of genetic testing: evidence from a survey amongst various genetics professionals. J Commun Genet. 2010;1:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s12687-010-0004-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rantanen E, Hietala M, Kristoffersson U, Nippert I, Schmidtke J, Sequeiros J, Kaariainen H. Regulations and practices of genetic counselling in 38 European countries: the perspective of national representatives. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(10):1208–1216. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequeiros J (2010) Regulating genetic testing: the relevance of appropriate definitions. In: Kristoffersson U, Schmidtke J, Cassiman JJ (eds) Quality issues in clinical genetic services. Springer, Berlin pp 23–32

- Sequeiros J, Paneque M, Guimarães B, Rantanen E, Javaher P, Nippert I, Schmidtke J, Kääriäainen H, Kristoffersson U, Cassiman JJ (in this issue) The Wide Variation of Definitions of Genetic Testing in International Recommendations, Guidelines and Reports [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Trubeck DM, Cottrell P, Nance M (2005): Soft law, hard law, and European integration: toward a theory of hybridity. University of Wisconsin–Madison, 21 April 2005; http://law.wisc.edu/facstaff/trubek/hybriditypaperapril2005.pdf. Accessed 29 December 2011

- Varga O, Sequeiros J (2008) Definitions of genetic testing in European and other legal documents. http://www.eurogentest.org/web/files/public/unit6/core_competences/BackgroundDocDefinitionsLegislationV10-FinalDraft.pdf. Accessed 1 January 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- WHO (2008a) Ethical, legal, social implications & issues of human genome project genetics resource directory (ELSI ReD); http://www.who.int/genomics/elsi/regulatory_data/en/index.html. Accessed 31 December 2008

- WHO (2008b) International Digest of Health Legislation (2008b); http://www.who.int/idhl-rils/frame.cfm?language=english. Accessed 31 December 2008

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 88 kb)