Abstract

Extracellular heat-shock protein 72 (eHsp72) expression during exercise-heat stress is suggested to increase with the level of hyperthermia attained, independent of the rate of heat storage. This study examined the influence of exercise at various intensities to elucidate this relationship, and investigated the association between eHsp72 and eHsp27. Sixteen male subjects cycled to exhaustion at 60% and 75% of maximal oxygen uptake in hot conditions (40°C, 50% RH). Core temperature, heart rate, oxidative stress, and blood lactate and glucose levels were measured to determine the predictor variables associated with eHsp expression. At exhaustion, heart rate exceeded 96% of maximum in both conditions. Core temperature reached 39.7°C in the 60% trial (58.9 min) and 39.0°C in the 75% trial (27.2 min) (P < 0.001). The rate of rise in core temperature was 2.1°C h−1 greater in the 75% trial than in the 60% trial (P < 0.001). A significant increase and correlation was observed between eHsp72 and eHsp27 concentrations at exhaustion (P < 0.005). eHsp72 was highly correlated with the core temperature attained (60% trial) and the rate of increase in core temperature (75% trial; P < 0.05). However, no common predictor variable was associated with the expression of both eHsps. The similarity in expression of eHsp72 and eHsp27 during moderate- and high-intensity exercise may relate to the duration (i.e., core temperature attained) and intensity (i.e., rate of increase in core temperature) of exercise. Thus, the immuno-inflammatory release of eHsp72 and eHsp27 in response to exercise in the heat may be duration and intensity dependent.

Keywords: Heat-shock proteins, Hyperthermia, Exhaustion, Core temperature

Introduction

Thermotolerance during a prolonged acute bout of exercise in the heat is characterised by the heat-shock response and adaptations associated with heat acclimation. The heat-shock response confers transient thermal tolerance, in part due to the expression of heat-shock proteins (Hsps). These highly conserved ubiquitous stress proteins are found in all eukaryotes and prokaryotes, and are synthesised by the cells of an organism in response to a variety of stimuli, including heat, oxidative, metabolic and chemical stress (Welch 1992; Morimoto et al. 1994). The classification of Hsps is based on function and molecular mass, ranging from 8 to 110 kDa (Schlesinger 1990; Welch 1992). This includes the constitutively expressed and stress-inducible Hsp70 family. Hsp72 in particular is responsive to heat stress and exercise (Locke 1997). Its extracellular expression (eHsp72), measured in plasma and serum, has been suggested as a potential signal, triggering innate immunity and stimulating the release of proinflammatory cytokines (Pockley et al. 1998; Asea et al. 2000; Njemini et al. 2003; Pockley et al. 2003; Njemini et al. 2004; Asea 2005; Noble et al. 2008). In humans, the contracting muscles do not appear to be a source of eHsp72 (Febbraio et al. 2002a), whereas the brain and hepatosplanchnic tissues are capable of releasing Hsp72 in the systemic circulation (Febbraio et al. 2002b; Lancaster et al. 2004).

Walsh et al. (2001) first demonstrated an increase in eHsp72 following a 60-min treadmill run in humans at 70% of maximal oxygen uptake ( ) in temperate conditions. Since then, others have also observed the upregulation of eHsp72 expression after prolonged exercise (Febbraio et al. 2002b), which appears to rely on the duration and intensity of exercise (Fehrenbach et al. 2005). Under conditions of heat stress, eHsp72 increases markedly during exercise (Marshall et al. 2006). The level of increase may be associated with the rise in core temperature, as walking to an end-point core temperature of 38.5°C in conditions eliciting high and low rates of heat storage resulted in a similar eHsp72 response (Amorim et al. 2008). However, the similarity in eHsp72 concentration between conditions may relate to the relatively low intensity of exercise and minimal increase in core temperature. Regardless, these observations are supported by previous findings showing a stronger relationship between eHsp72 and final core temperature, compared with the rate of heat storage (Ruell et al. 2006). Measures taken 24 h post-exercise underscore the transient nature of this increase with a return in eHsp72 to basal levels (Walsh et al. 2001; Fehrenbach et al. 2005).

) in temperate conditions. Since then, others have also observed the upregulation of eHsp72 expression after prolonged exercise (Febbraio et al. 2002b), which appears to rely on the duration and intensity of exercise (Fehrenbach et al. 2005). Under conditions of heat stress, eHsp72 increases markedly during exercise (Marshall et al. 2006). The level of increase may be associated with the rise in core temperature, as walking to an end-point core temperature of 38.5°C in conditions eliciting high and low rates of heat storage resulted in a similar eHsp72 response (Amorim et al. 2008). However, the similarity in eHsp72 concentration between conditions may relate to the relatively low intensity of exercise and minimal increase in core temperature. Regardless, these observations are supported by previous findings showing a stronger relationship between eHsp72 and final core temperature, compared with the rate of heat storage (Ruell et al. 2006). Measures taken 24 h post-exercise underscore the transient nature of this increase with a return in eHsp72 to basal levels (Walsh et al. 2001; Fehrenbach et al. 2005).

Similarly, Hsp27, a smaller member of the Hsp family, confers cellular protection and also rapidly returns to basal levels once the homeostatic challenge has been removed (Arrigo 2007). This allows for the overexpression of Hsp27 when cytoprotection is required (Concannon et al. 2003). Accordingly, extracellular (eHsp27) levels increase markedly in the venous blood of healthy human subjects following maximal cycling exercise in thermoneutral conditions (Jammes et al. 2009). Significant eHsp27 increases are also noted in response to exhaustive hand grip exercise under hyperoxic conditions (Brerro-Saby et al. 2010), which indicates that both eHsp72 and eHsp27 expressions are upregulated under physiological stress.

Interestingly, it has been suggested that eHsp72 concentration may serve as an aid in the diagnosis of exertional heat-related illnesses. Ruell et al. (2006) observed that early clinical signs of heat stroke (i.e., neurological dysfunction) were associated with higher levels of eHsp72 immediately following a 14-km running event. Recently, it was proposed that elevated levels of eHsp70 during exercise and the increased release of eHsp70 from lymphocytes during high-intensity exercise may induce a sense of fatigue in the central nervous system (CNS) (Heck et al. 2011). However, the relationship between eHsp72 and exhaustive exercise in the heat at different intensities, which may elicit various rates of expression, is not well understood. Moreover, the association between eHsp72 and eHsp27 concentration remains largely unexplored.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to (1) investigate the relationship between eHsp72 concentration and exercise to exhaustion in a hot environment at moderate and high intensities, and (2) determine whether eHsp72 and eHsp27 follow a similar pattern of expression. Measurements of eHsp were performed prior to exercise, immediately on reaching exhaustion and 24 h post-exercise. It was hypothesised that eHsp72 levels would differ between intensities at exhaustion because of the attainment of a higher core temperature in the moderate exercise trial. It was further hypothesised that a similar pattern of expression would characterise eHsp72 and eHsp27 concentrations at exhaustion.

Methods

Subjects

Sixteen healthy male subjects unacclimatized to heat participated in this study. Their physical characteristics for age, body mass, height, and  were 26.4 ± 4.5 years, 72.9 ± 7.5 kg, 180.3 ± 5.9 cm and 4.4 ± 0.6 l·min−1. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney and written consent was obtained after explanation of risks and discomforts.

were 26.4 ± 4.5 years, 72.9 ± 7.5 kg, 180.3 ± 5.9 cm and 4.4 ± 0.6 l·min−1. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney and written consent was obtained after explanation of risks and discomforts.

Pre-experimental protocol

Prior to undertaking the experimental trials of the study, height and nude body mass (Mettler ID1, Greifensee, Switzerland) were taken. Maximal heart rate and oxygen uptake was measured in a thermoneutral environment (20°C, 40% relative humidity (RH)) with participants cycling on an electronically braked cycle ergometer (Schoberer Rad Meßtechnik, Jülich, Germany) for 5 min at four submaximal steady-state power outputs (20 min total) followed by a 5-min rest period and then incremental increase in power (25 W min−1) until volitional fatigue. Power outputs corresponding to 60% (181.9 ± 35.0 W) and 75% (238.2 ± 47.4 W)  were calculated from the

were calculated from the  :power output relationship. Saddle and handlebar positions were adjusted by the subject to their preferred cycling position and remained unchanged for all trials. Subjects were familiarised with the experimental protocol and climatic conditions by cycling in the heat for 20–30 min at 60%

:power output relationship. Saddle and handlebar positions were adjusted by the subject to their preferred cycling position and remained unchanged for all trials. Subjects were familiarised with the experimental protocol and climatic conditions by cycling in the heat for 20–30 min at 60%  following the incremental test to exhaustion. During all trials subjects wore cycling shorts, socks, and shoes.

following the incremental test to exhaustion. During all trials subjects wore cycling shorts, socks, and shoes.

Experimental protocol

Subjects presented to the laboratory 60 min prior to testing at the same time of day, on two occasions separated by 4 to 7 days. Before each visit the subjects were asked to refrain from strenuous exercise and avoid the consumption of caffeine and alcohol for at least 24 h. Upon arrival, subjects were asked to empty their bladder, were weighed and inserted a rectal thermistor probe. They then sat resting in a thermoneutral environment while being instrumented. A cannula was inserted into a ventral forearm vein to collect a resting blood sample before the subjects entered the climate chamber. The cannula remained in the vein until completion of the trial and was systematically flushed with saline after sample collection to maintain patency. After instrumentation, the subjects entered the climate chamber, were weighed, and mounted the cycle ergometer. They were then instructed to exercise until exhaustion in a hot environment (40°C, 50% RH) with convective airflow of 4.17 m s−1. The experimental trials were randomly assigned and required subjects to cycle at 60% and 75%  . All subjects were instructed and encouraged to exercise for as long as possible while unaware of heart rate and time. Exhaustion was defined as the point at which (1) a subject volitionally terminated exercise, or (2) power output could no longer be maintained at a cadence above 60 rev min−1. In compliance with ethical approval, exercise was terminated if a subject attained a rectal temperature of 39.9°C.

. All subjects were instructed and encouraged to exercise for as long as possible while unaware of heart rate and time. Exhaustion was defined as the point at which (1) a subject volitionally terminated exercise, or (2) power output could no longer be maintained at a cadence above 60 rev min−1. In compliance with ethical approval, exercise was terminated if a subject attained a rectal temperature of 39.9°C.

Exercise measurements

Expired respiratory gases during the  protocol were collected for 1 min using the Douglas bag method and analysed for fractions of O2 and CO2 using zirconium cell-based sensors (Pm1111E and IrI507, respectively; Servomex, Sugar Land, TX, USA). Expiratory volumes were determined using a dry gas meter (Harvard, UK) and standard temperature, pressure and dry gas values were calculated according to corrected barometric pressure and temperature. During the experimental trials, heart rate was monitored telemetrically and recorded continuously with a Polar transmitter–receiver (T-31 Polar Electro, Lake Success, NY, USA). Rectal temperature was also measured continuously and logged on a portable data logger (T-Logger, University of Sydney, Australia) by a thermistor probe (YSI 400 series, Mallinckrodt Medical, MO, USA) inserted to a depth of 12 cm past the anal sphincter. The T-Logger was calibrated before and after the study within a temperature range of 20°C to 45°C. The rectal temperature area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using a modification to the trapezium rule (Hubbard et al. 1977) when rectal temperature exceeded 38.5°C (Cheuvront et al. 2008). It was calculated as:

protocol were collected for 1 min using the Douglas bag method and analysed for fractions of O2 and CO2 using zirconium cell-based sensors (Pm1111E and IrI507, respectively; Servomex, Sugar Land, TX, USA). Expiratory volumes were determined using a dry gas meter (Harvard, UK) and standard temperature, pressure and dry gas values were calculated according to corrected barometric pressure and temperature. During the experimental trials, heart rate was monitored telemetrically and recorded continuously with a Polar transmitter–receiver (T-31 Polar Electro, Lake Success, NY, USA). Rectal temperature was also measured continuously and logged on a portable data logger (T-Logger, University of Sydney, Australia) by a thermistor probe (YSI 400 series, Mallinckrodt Medical, MO, USA) inserted to a depth of 12 cm past the anal sphincter. The T-Logger was calibrated before and after the study within a temperature range of 20°C to 45°C. The rectal temperature area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using a modification to the trapezium rule (Hubbard et al. 1977) when rectal temperature exceeded 38.5°C (Cheuvront et al. 2008). It was calculated as:  . Ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) (Borg 1982) and thermal comfort (Bedford 1936) were recorded every 10 min. During each trial, subjects were permitted to drink ad libitum. A 24-h food diary was kept and subjects were asked to replicate their diet before each exercise trial. Changes in body mass were determined at the conclusion of each trial (Pugh et al. 1967) and corrected for moisture loss due to the exchange of O2 and CO2 (Mitchell et al. 1972), fluid ingestion, and sweat trapped in clothing.

. Ratings of perceived exertion (RPE) (Borg 1982) and thermal comfort (Bedford 1936) were recorded every 10 min. During each trial, subjects were permitted to drink ad libitum. A 24-h food diary was kept and subjects were asked to replicate their diet before each exercise trial. Changes in body mass were determined at the conclusion of each trial (Pugh et al. 1967) and corrected for moisture loss due to the exchange of O2 and CO2 (Mitchell et al. 1972), fluid ingestion, and sweat trapped in clothing.

Haematological and biochemical measurements

Venous blood samples were collected at rest (pre-exercise control), after 10 and 30 min of exercise, at exhaustion (i.e., termination of exercise), and 24 h after exercise completion. They were immediately placed in EDTA and lithium heparin treated tubes on ice. Blood glucose and lactate concentration were measured in duplicate using the automated glucose oxidase and lactate oxidase methods, respectively (EML 105, Radiometer Pacific, Copenhagen, Denmark). Hematocrit and hemoglobin concentrations were measured on EDTA-treated blood (Sysmex KX-21 N, Kobe, Japan) to estimate percent changes in resting plasma volume (Dill and Costill 1974). Further, EDTA-treated blood samples were centrifuged at 1,800 rev min−1 for 10 min at 4°C. The plasma was then removed and stored at −85°C until analysis. Plasma Hsp72 and Hsp27 were analysed using R and D Systems kits (DYC1663 and DYC1580 respectively, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to manufacturer instructions and previous research (Molvarec et al. 2009). All measurements were made in duplicate. Plasma Hsp72/27 samples were diluted 1/5 and 1/10, respectively, in a solution of 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS pH 7.4. The intra/inter-assay variability was 5/9% and 8/18% and the detection range of the assays were 0.15–10 and 0.03–2 ng/ml for Hsp72 and Hsp27, respectively. Malondialdehyde (MDA), a measure of lipid peroxidation, was estimated from a modification of the thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances (TBARS) assay described by Lawler et al. (1994).

Statistical analysis

All statistical calculations were performed using PASW software version 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, US). A two-way (time-by-trial) repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to test significance between and within trials. Preceding any statistical analysis, all outcome variables were assessed for normality. Whenever outcome variables displayed departure from normality, logarithmic transformations were applied. Outcome variables were tested using Mauchly’s procedure for sphericity. Whenever the data violated the assumption of sphericity, P values and adjusted degrees of freedom based on Greenhouse–Geisser correction were reported instead. Where significant interaction effects were established, pairwise differences were identified using the Bonferroni post hoc analysis procedure adjusted for multiple comparisons. Multiple regression analysis was used with the enter method to determine predictors of exercise-induced increases in eHsp72 and eHsp27 concentrations. The significance level was set at P < 0.05. All values are expressed as means ± SD.

Results

Exercise responses

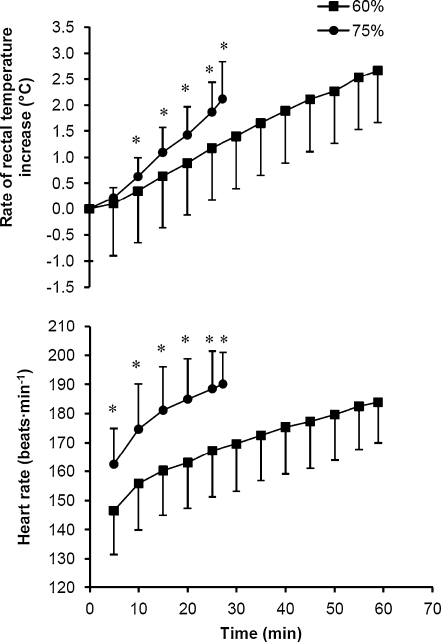

Exhaustion in the 60% trial occurred at 58.9 ± 10.9 min, and in the 75% trial at 27.2 ± 9.0 min (P < 0.001). During the 60% trial, three subjects had to be stopped on reaching the University of Sydney Human Ethics Committee rectal temperature limit of 39.9°C, whereas one subject terminated exercise prematurely in the 75% trial. Rectal temperature was similar at the onset of the 60% and 75% trials, 37.0 ± 0.3°C and 36.9 ± 0.3°C, respectively. However, final rectal temperatures were different reaching 39.7 ± 0.4°C (60%) and 39.0 ± 0.5°C (75%) (P < 0.001). The rate of increase in rectal temperature was 2.1 ± 1.4°C h−1 greater in the 75% trial than in the 60% trial (Fig. 1) (P < 0.001). This rate of rise was paralleled in the heart rate response (Fig. 1), which was strongly correlated with that of rectal temperature in both the 60% (r = 0.64) and 75% (r = 0.60) trials (P < 0.001). On reaching exhaustion, heart rate in the 60% trial was 96.2 ± 4.0% of maximum, and in the 75% trial 99.5 ± 1.9% of maximum (P < 0.01). The calculated AUC was significantly greater in the 60% trial (17.0 ± 9.0°C min−1) compared with the 75% trial (3.2 ± 4.3°C min−1) (P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Rate of increase in rectal temperature and heart rate during exercise to exhaustion at 60% and 75%  in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity). Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference between 60% and 75%, P < 0.005

in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity). Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference between 60% and 75%, P < 0.005

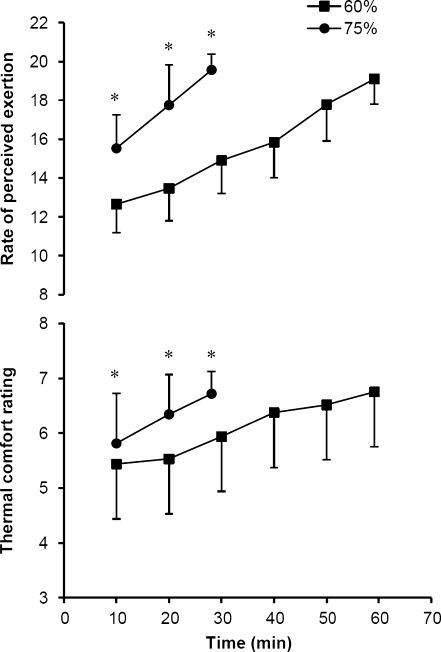

RPE and thermal comfort are presented in Fig. 2. Although initial ratings (10 min) and the rate of increase were significantly different between the 60% and 75% trials, final RPE and thermal comfort were similar on reaching exhaustion (P < 0.005). Blood glucose measures decreased slightly at 10 min of exercise (4.5 ± 0.7 and 4.8 ± 0.6 mmol l−1) in both 60% and 75% trials compared with pre-exercise baseline (5.1 ± 1.1 and 4.9 ± 0.7 mmol l−1), and then increased on reaching exhaustion (5.0 ± 0.7 and 5.7 ± 0.9 mmol l−1). Significant main effects of time (P < 0.01) and condition (60% vs. 75%; P < 0.05) were noted in blood glucose levels, but there was no difference between trials. Increases in blood lactate, while significantly different, were noted in both trials (P < 0.001). In the 60% trial, pre-exercise blood lactate was 1.6 ± 0.3 mmol l−1, increasing to 3.9 ± 2.0 mmol l−1 at 10 min of exercise and 4.8 ± 2.5 mmol l−1 at exhaustion (P < 0.001). In the 75% trial, blood lactate increased from 1.7 ± 0.6 mmol l−1 (pre-exercise baseline) to 9.2 ± 3.9 mmol l−1 (10 min) and 10.9 ± 4.8 mmol l−1 (exhaustion) (P < 0.001). Percent changes in plasma volume calculations indicated a reduction at 10 min of exercise (−7.9 ± 2.7% and −10.9 ± 3.9%) and on reaching exhaustion (−8.8 ± 3.7% and −11.4 ± 4.4%) in both 60% and 75% trials, respectively (P < 0.001). The decline in plasma volume was greater in the 75% trial (P < 0.05). The percent change in body mass was minimal and similar between trials, 0.7 ± 0.8% (60%) and 0.5 ± 0.4% (75%).

Fig. 2.

Ratings of perceived exertion and thermal comfort during exercise to exhaustion at 60% and 75%  in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity). Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference between 60% and 75%, P < 0.005

in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity). Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference between 60% and 75%, P < 0.005

Heat-shock protein and oxidative stress responses

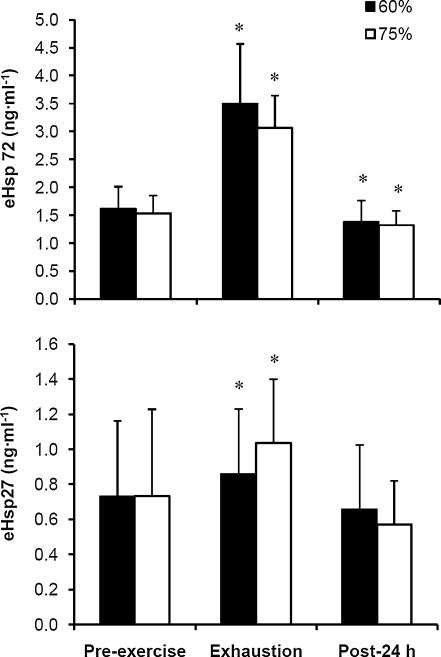

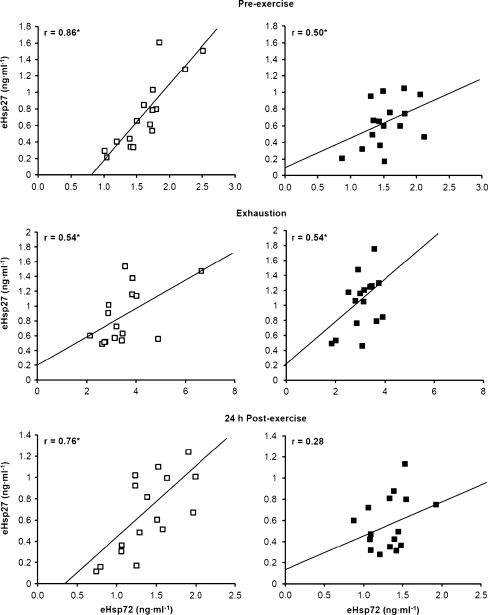

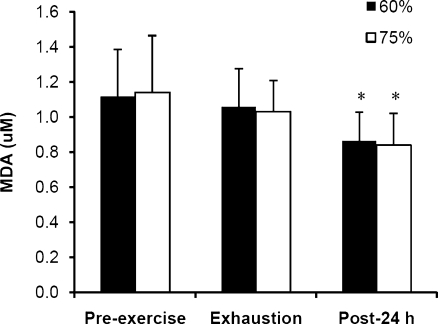

The expression of both eHsp72 and eHsp27 increased significantly from pre-exercise baseline to exhaustion in the 60% and 75% trials (Fig. 3; P < 0.001). During the following 24 h, eHsp72 decreased to levels below baseline (P < 0.05), whereas eHsp27 returned to basal levels. No difference was noted between the 60% and 75% trials in eHsp72 and eHsp27 concentration. There was a strong correlation between eHsp72 and eHsp27 in the 60% trial at all blood sampling time points, whereas in the 75% trial, correlations were observed at pre-exercise baseline and exhaustion (Fig. 4; P < 0.05). A significant decline in MDA was observed 24 h after exercise compared with pre-exercise and exhaustion values (Fig. 5; P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Plasma heat-shock protein 72 (eHsp72) and 27 (eHsp27) prior to exercise at 60% and 75%  in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity), on reaching exhaustion and 24 h after exercise completion. Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference from pre-exercise, P < 0.05

in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity), on reaching exhaustion and 24 h after exercise completion. Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference from pre-exercise, P < 0.05

Fig. 4.

Correlations between plasma heat-shock protein 72 (eHsp72) and 27 (eHsp27) prior to exercise at 60% (white square) and 75% (black square)  in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity), on reaching exhaustion and 24 h after exercise completion. Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant correlation, P < 0.05

in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity), on reaching exhaustion and 24 h after exercise completion. Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant correlation, P < 0.05

Fig. 5.

Malondialdehyde (MDA) prior to exercise at 60% and 75%  in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity), on reaching exhaustion and 24 h after exercise completion. Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference from pre-exercise and exhaustion, P < 0.001

in hot conditions (40°C and 50% relative humidity), on reaching exhaustion and 24 h after exercise completion. Values are means ± SD for 16 subjects. *Significant difference from pre-exercise and exhaustion, P < 0.001

In the 60% trial, a significant regression analysis model emerged with eHsp72 expression (P < 0.05). Rectal temperature and  were significant predictor variables of eHsp72 expression with an adjusted R2 = 0.33; rectal temperature β = 0.862, P = 0.016, and

were significant predictor variables of eHsp72 expression with an adjusted R2 = 0.33; rectal temperature β = 0.862, P = 0.016, and  β = −0.914, P = 0.012. In the 75% trial, the rate of increase in rectal temperature was a significant predictor variable of eHsp72 expression with an adjusted R2 = 0.219 and β = −0.52, P = 0.039. For the expression of eHsp27, blood glucose was a significant predictor variable in the 60% trial with an R2 = 0.239 and β = 0.538, P = 0.032. No predictor variables were found for eHsp27 concentration in the 75% trial. In the 75% trial,

β = −0.914, P = 0.012. In the 75% trial, the rate of increase in rectal temperature was a significant predictor variable of eHsp72 expression with an adjusted R2 = 0.219 and β = −0.52, P = 0.039. For the expression of eHsp27, blood glucose was a significant predictor variable in the 60% trial with an R2 = 0.239 and β = 0.538, P = 0.032. No predictor variables were found for eHsp27 concentration in the 75% trial. In the 75% trial,  was a significant predictor of MDA concentration with an adjusted R2 = 0.351, β = −0.628, P = 0.009.

was a significant predictor of MDA concentration with an adjusted R2 = 0.351, β = −0.628, P = 0.009.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine the influence of exercise intensity on eHsp72 expression when cycling to exhaustion in a hot environment, and to elucidate the relationship between eHsp72 and eHsp27. As such, this study provides novel in vivo data of human plasma Hsp expression following exercise to exhaustion at moderate and high exercise intensities in the heat. In contrast to our hypothesis, no difference in eHsp72 concentration was observed between the 60% and 75% trials on reaching exhaustion, despite a rectal temperature difference of 0.7°C. However, a strong correlation was noted between eHsp72 and eHsp27 in both trials (Fig. 4). The increase in eHsp72 was strongly correlated with the increase in core temperature in the 60% trial and with the rate of increase in rectal temperature in the 75% trial. These observations suggest that the release of eHsp72 and eHsp27 in response to an acute physiological challenge under heat stress may be both duration and intensity dependent.

The unique feature of the protocol utilised in this study was the use of two different exercise intensities in the heat eliciting distinct homeostatic disturbances (Fig. 1). Essentially, the rate of increase in rectal temperature was manipulated, as was the temperature attained on exhaustion. Concomitantly, the development of metabolic and cardiovascular strain varied between exercise at 60% and 75%  . Previous research has suggested that the expression of eHsp72 is a function of the core temperature attained following an acute bout of exercise, rather than the rate at which hyperthermia develops (i.e., the rate of heat storage) (Ruell et al. 2006; Amorim et al. 2008). Accordingly, a significant correlation has been noted between eHsp72 concentration and core temperature in athletes completing a race in cool environmental conditions (21°C, 33% RH and 28 km h−1 wind velocity) (Ruell et al. 2006). It was further reported that while core temperature was not the sole factor mediating the rise in eHsp72 concentration, it accounted for 42% of the variance in eHsp measured immediately post-run. Others have noted that a treadmill walk in the heat to elicit a core temperature of 38.5°C via high (1.04 W m−2 min−1) and low (0.54 W m−2 min−1) rates of heat storage resulted in similar levels of eHsp72 concentration (Amorim et al. 2008). Recently, Selkirk et al. (2009) observed a temperature-dependent increase in eHsp72 in endurance-trained subjects attaining a higher core temperature (39.7°C) during walking exercise to exhaustion in the heat, compared with sedentary-untrained subjects (39.1°C). Data from this study add to these observations by demonstrating that the increase in eHsp72 and eHsp27 is not exclusively mediated by a rise in core temperature during exercise in the heat, especially at a high intensity. This observation is reinforced by AUC calculations showing a greater interval time spent above a rectal temperature of 38.5°C in the 60% trial, but yielding a similar eHsp response to that noted in the 75% trial. Moreover, while rectal temperature was a significant predictor variable of eHsp72 concentration in the 60% trial, the rate of increase in rectal temperature was a strong predictor in the 75% trial. However, no common predictor variable was associated with the expression of both eHsp72 and eHsp27 in the 60% and 75% trials. Other variables associated with the increase in plasma Hsp were

. Previous research has suggested that the expression of eHsp72 is a function of the core temperature attained following an acute bout of exercise, rather than the rate at which hyperthermia develops (i.e., the rate of heat storage) (Ruell et al. 2006; Amorim et al. 2008). Accordingly, a significant correlation has been noted between eHsp72 concentration and core temperature in athletes completing a race in cool environmental conditions (21°C, 33% RH and 28 km h−1 wind velocity) (Ruell et al. 2006). It was further reported that while core temperature was not the sole factor mediating the rise in eHsp72 concentration, it accounted for 42% of the variance in eHsp measured immediately post-run. Others have noted that a treadmill walk in the heat to elicit a core temperature of 38.5°C via high (1.04 W m−2 min−1) and low (0.54 W m−2 min−1) rates of heat storage resulted in similar levels of eHsp72 concentration (Amorim et al. 2008). Recently, Selkirk et al. (2009) observed a temperature-dependent increase in eHsp72 in endurance-trained subjects attaining a higher core temperature (39.7°C) during walking exercise to exhaustion in the heat, compared with sedentary-untrained subjects (39.1°C). Data from this study add to these observations by demonstrating that the increase in eHsp72 and eHsp27 is not exclusively mediated by a rise in core temperature during exercise in the heat, especially at a high intensity. This observation is reinforced by AUC calculations showing a greater interval time spent above a rectal temperature of 38.5°C in the 60% trial, but yielding a similar eHsp response to that noted in the 75% trial. Moreover, while rectal temperature was a significant predictor variable of eHsp72 concentration in the 60% trial, the rate of increase in rectal temperature was a strong predictor in the 75% trial. However, no common predictor variable was associated with the expression of both eHsp72 and eHsp27 in the 60% and 75% trials. Other variables associated with the increase in plasma Hsp were  and blood glucose. In the present study, runners with a higher

and blood glucose. In the present study, runners with a higher  had lower eHsp72 levels at the end of exercise, whereas glucose appears to be important in regulating eHsp27 concentration.

had lower eHsp72 levels at the end of exercise, whereas glucose appears to be important in regulating eHsp27 concentration.

To our knowledge, the influence of exercise intensity on plasma and serum Hsp72 in humans has only been investigated in cool climatic conditions (Fehrenbach et al. 2005). It was shown that competitive aerobic exercise (i.e., a marathon) induces greater levels of eHsp72 compared with more intensive, shorter duration interval-type training. However, it was also demonstrated that exhaustive exercise at 80%  induces greater levels of eHsp72 compared with exercise at 60%

induces greater levels of eHsp72 compared with exercise at 60%  of the same duration. Thus, the exercise-induced increase in eHsp72 concentration was described as both duration and intensity dependent (Fehrenbach et al. 2005). Accordingly, the similar level of expression in eHsp72 and eHsp27 noted in this study during moderate and high intensity exercise, may relate to both duration (60% trial) and intensity (75% trial) (Fig. 3). In the 60% trial, the increase in eHsp72 was correlated with the core temperature attained, whereas in the 75% trial, eHsp72 increased in response to the rate of rise in core temperature and enhanced metabolic demand. Although this study is limited by the lack of a condition in which exercise duration was matched between different exercise intensities, we speculate that eHsp72 and eHsp27 expression is duration and intensity dependent during exhaustive exercise under heat stress conditions. Based on cellular location, Hsp70 has both an anti-inflammatory (intracellular) and pro-inflammatory (extracellular) effect on leucocytes (Noble et al. 2008). In the extracellular milieu, Hsp72 is suggested to improve immune function. For example, it has been shown that the concentration of eHsp70 is highly correlated with oxidative stress, inflammation, cardiovascular, and pulmonary disease (Ogawa et al. 2008), and that the artificial increase in eHsp70 via glutamine supplementation is associated with a reduced hospital treatment period in critically ill patients (Ziegler et al. 2005). As such, an increase in eHsp72 may represent an important immuno-inflammatory response to protect the organism against physiological disturbances (Heck et al. 2011). During the exercise recovery period, eHsp72 may remain elevated to limit the response time to a pathogenic challenge (Yamada et al. 2008). Although the precise role of eHsp27 is less well defined, increases in the extracellular concentration of eHsp27 are also associated with elevations in oxidative stress (Brerro-Saby et al. 2010). An interesting finding was a reduced eHsp72 concentration 24 h following the cessation of exercise (Fig. 3). A similar finding was noted in a previous study (Marshall et al. 2006) following exercise in the heat on two consecutive days. It was suggested that the lower resting concentration was due to an enhanced cellular uptake by cells unable to synthesis their own Hsps.

of the same duration. Thus, the exercise-induced increase in eHsp72 concentration was described as both duration and intensity dependent (Fehrenbach et al. 2005). Accordingly, the similar level of expression in eHsp72 and eHsp27 noted in this study during moderate and high intensity exercise, may relate to both duration (60% trial) and intensity (75% trial) (Fig. 3). In the 60% trial, the increase in eHsp72 was correlated with the core temperature attained, whereas in the 75% trial, eHsp72 increased in response to the rate of rise in core temperature and enhanced metabolic demand. Although this study is limited by the lack of a condition in which exercise duration was matched between different exercise intensities, we speculate that eHsp72 and eHsp27 expression is duration and intensity dependent during exhaustive exercise under heat stress conditions. Based on cellular location, Hsp70 has both an anti-inflammatory (intracellular) and pro-inflammatory (extracellular) effect on leucocytes (Noble et al. 2008). In the extracellular milieu, Hsp72 is suggested to improve immune function. For example, it has been shown that the concentration of eHsp70 is highly correlated with oxidative stress, inflammation, cardiovascular, and pulmonary disease (Ogawa et al. 2008), and that the artificial increase in eHsp70 via glutamine supplementation is associated with a reduced hospital treatment period in critically ill patients (Ziegler et al. 2005). As such, an increase in eHsp72 may represent an important immuno-inflammatory response to protect the organism against physiological disturbances (Heck et al. 2011). During the exercise recovery period, eHsp72 may remain elevated to limit the response time to a pathogenic challenge (Yamada et al. 2008). Although the precise role of eHsp27 is less well defined, increases in the extracellular concentration of eHsp27 are also associated with elevations in oxidative stress (Brerro-Saby et al. 2010). An interesting finding was a reduced eHsp72 concentration 24 h following the cessation of exercise (Fig. 3). A similar finding was noted in a previous study (Marshall et al. 2006) following exercise in the heat on two consecutive days. It was suggested that the lower resting concentration was due to an enhanced cellular uptake by cells unable to synthesis their own Hsps.

The correlation between plasma eHsp72 and eHsp27 may indicate a common mechanism of release (Fig. 4). Although hepatosplanchnic and brain tissue remain the principle sources of Hsp72 release into the systemic circulation (Febbraio et al. 2002b; Lancaster et al. 2004), it is suggested that exosomes, small vesicles secreted following the fusion of multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane, provide the secretory pathway for cells to actively release specific Hsps during exercise (Lancaster and Febbraio 2005; De Maio 2011; Ogawa et al. 2011). An alternative mechanism of expression proposes that during exercise, eHsp72 is triggered by circulating ATP in the extracellular milieu (Ogawa et al. 2011), potentially released during muscle contraction (Mortensen et al. 2009). Ultimately, the release of eHsp72 into the systemic circulation likely originates from several tissues and cell types, which could involve specific mechanisms of release and various inducing factors (Mambula et al. 2007).

During exercise at both intensities, RPE and thermal comfort increased significantly until exhaustion (Fig. 2). Such increases in RPE, in association with the rise in core temperature during exhaustive exercise in the heat, have previously been linked with the development of fatigue and alterations in cerebral activity (i.e., an increase in the α/β index), indicating suppressed arousal (Nielsen et al. 2001; Nybo and Nielsen 2001). However, the increased index was also correlated with the rise in heart rate, which might signal a cardiovascular limitation to exercise (Périard et al. 2011a, b). Notwithstanding, the increased release of eHsp70 during exercise has recently been suggested to trigger the sensation of fatigue within the CNS (Heck et al. 2011). It is proposed that CNS cells may take up circulating Hsp70, which in turn would act as a stressor or danger signal from peripheral cells, enhancing or initiating a greater sense of fatigue (Heck et al. 2011). However, elevated levels of eHsp72 are associated with the rise in core temperature and a greater severity of the symptoms related to heat illnesses (Ruell et al. 2006). Thus, if the release of eHsp70 was a CNS fatigue-signalling mechanism, it may be inferred that subjects would reduce their effort in conjunction with the development of the sensation of fatigue, avoiding a potentially life-threatening situation. It is also suggested that eHsp70 in export vesicles may have a different role depending on vesicle composition, source and cell target (De Maio 2011). Perhaps a particular type of vesicle containing Hsp72 does trigger the sensation of fatigue. However, further research is required to analyse the composition of eHsp72, its expression and its concentration in different types of vesicles.

Lipid peroxidation, as reflected by circulating MDA, is indicative of free radical production. In a recent study, Jammes et al. (2009) observed a negative correlation between TBARS and eHsp72 or eHsp27 following incremental cycling to fatigue in temperate conditions. The association was noted when data from subjects suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome and healthy controls were pooled, and indicated enhanced post-exercise oxidative stress in those having the lowest eHsp response (i.e., chronic fatigue patients). In the current study, MDA did not increase during exercise in either condition, or correlate with either eHsp at exhaustion (Fig. 5). The lack of increase during exercise reflects previous observations demonstrating an increase in MDA only during exhaustive maximal exercise, as compared to exercise at 40% and 70%  (Lovlin et al. 1987). It has also been shown that eHsp27 concentration increases quickly in response to the combination of hyperoxia and maximal isometric exercise to fatigue, possibly to counterbalance the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (Wu 1995; Brerro-Saby et al. 2010). Thus, the immuno-inflammatory release of eHsp27 occurs rapidly in venous blood after maximal exercise (Jammes et al. 2009), which corroborates that noted in the current study.

(Lovlin et al. 1987). It has also been shown that eHsp27 concentration increases quickly in response to the combination of hyperoxia and maximal isometric exercise to fatigue, possibly to counterbalance the excessive production of reactive oxygen species (Wu 1995; Brerro-Saby et al. 2010). Thus, the immuno-inflammatory release of eHsp27 occurs rapidly in venous blood after maximal exercise (Jammes et al. 2009), which corroborates that noted in the current study.

In summary, the present observations demonstrate the similarity in eHsp72 and eHsp27 expressions during exhaustive exercise at moderate and high exercise intensities in the heat. They also highlight the duration and intensity-dependent nature of this expression. In the 60% trial, eHsp72 was associated with the rectal temperature reached at exhaustion, likely due to the more progressive development of hyperthermia (i.e., duration dependent). In the 75% trial, a relationship emerged between eHsp72 and the rate of increase in rectal temperature, possibly because of greater metabolic demand and energy conversion increasing rectal temperature (i.e., intensity dependent). Further research is required however to fully elucidate this relationship and determine the precise function and origin of each eHsp.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the subjects that participated in this investigation. The authors also thank Rhys Philips, Madeline Lynch, Colin Tuohy, Carl Cheah, Angelina Tan, and Thomas Wüthrich for their help with data collection. This work was supported by the University of Sydney Faculty of Health Sciences.

References

- Amorim FT, Yamada PM, Robergs RA, Schneider SM, Moseley PL. The effect of the rate of heat storage on serum heat shock protein 72 in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:965–972. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0850-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo AP. The cellular “networking” of mammalian Hsp27 and its functions in the control of protein folding, redox state and apoptosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;594:14–26. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-39975-1_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A. Stress proteins and initiation of immune response: chaperokine activity of hsp72. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2005;11:34–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A, Kraeft SK, Kurt-Jones EA, Stevenson MA, Chen LB, Finberg RW, Koo GC, Calderwood SK. HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat Med. 2000;6:435–442. doi: 10.1038/74697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford T (1936) The warmth factor in comfort at work: a physiological study of heating and ventilation. Industrial Health Research Board Report No. 76

- Borg GA. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brerro-Saby C, Delliaux S, Steinberg JG, Boussuges A, Gole Y, Jammes Y. Combination of two oxidant stressors suppresses the oxidative stress and enhances the heat shock protein 27 response in healthy humans. Metabolism. 2010;59:879–886. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheuvront SN, Chinevere TD, Ely BR, Kenefick RW, Goodman DA, McClung JP, Sawka MN. Serum S-100[beta] response to exercise-heat strain before and after acclimation. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1477–1482. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31816d65a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concannon CG, Gorman AM, Samali A. On the role of Hsp27 in regulating apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2003;8:61–70. doi: 10.1023/A:1021601103096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maio A. Extracellular heat shock proteins, cellular export vesicles, and the Stress Observation System: a form of communication during injury, infection, and cell damage: it is never known how far a controversial finding will go! Dedicated to Ferruccio Ritossa. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2011;16:235–249. doi: 10.1007/s12192-010-0236-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill DB, Costill DL. Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37:247–248. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.2.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio MA, Steensberg A, Walsh R, Koukoulas I, Hall G, Saltin B, Pedersen BK. Reduced glycogen availability is associated with an elevation in HSP72 in contracting human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2002;538(Pt 3):911–917. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febbraio MA, Ott P, Nielsen HB, Steensberg A, Keller C, Krustrup P, Secher NH, Pedersen BK. Exercise induces hepatosplanchnic release of heat shock protein 72 in humans. J Physiol. 2002;544:957–962. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.025148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehrenbach E, Niess AM, Voelker K, Northoff H, Mooren FC. Exercise intensity and duration affect blood soluble HSP72. Int J Sports Med. 2005;26:552–557. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-830334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heck TG, Schöler CM, Bittencourt PI. HSP70 expression: does it a novel fatigue signalling factor from immune system to the brain? Cell Biochem Funct. 2011;29:215–226. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard RW, Bowers WD, Matthew WT, Curtis FC, Criss RE, Sheldon GM, Ratteree JW. Rat model of acute heatstroke mortality. J Appl Physiol. 1977;42:809–816. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1977.42.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jammes Y, Steinberg JG, Delliaux S, Brégeon F. Chronic fatigue syndrome combines increased exercise-induced oxidative stress and reduced cytokine and Hsp responses. J Intern Med. 2009;266:196–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster GI, Febbraio MA. Mechanisms of stress-induced cellular HSP72 release: implications for exercise-induced increases in extracellular HSP72. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2005;11:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster GI, Møller K, Nielsen B, Secher NH, Febbraio MA, Nybo L. Exercise induces the release of heat shock protein 72 from the human brain in vivo. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:276–280. doi: 10.1379/CSC-18R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler JM, Powers SK, Dijk H, Visser T, Kordus MJ, Ji LL. Metabolic and antioxidant enzyme activities in the diaphragm: effects of acute exercise. Respir Physiol. 1994;96:139–149. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(94)90122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke M. The cellular stress response to exercise: role of stress proteins. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1997;25:105–136. doi: 10.1249/00003677-199700250-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovlin R, Cottle W, Pyke I, Kavanagh M, Belcastro AN. Are indices of free radical damage related to exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1987;56:313–316. doi: 10.1007/BF00690898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mambula SS, Stevenson MA, Ogawa K, Calderwood SK. Mechanisms for Hsp70 secretion: crossing membranes without a leader. Methods. 2007;43:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall HC, Ferguson RA, Nimmo MA. Human resting extracellular heat shock protein 72 concentration decreases during the initial adaptation to exercise in a hot, humid environment. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2006;11:129–134. doi: 10.1379/CSC-158R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JW, Nadel ER, Stolwijk JA. Respiratory weight losses during exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1972;32:474–476. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1972.32.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molvarec A, Rigó JJ, Lázár L, Balogh K, Makó V, Cervenak L, Mézes M, Prohászka Z. Increased serum heat-shock protein 70 levels reflect systemic inflammation, oxidative stress and hepatocellular injury in preeclampsia. Cell Stress and Chaperones. 2009;14:151–159. doi: 10.1007/s12192-008-0067-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto RI, Tissieres A, Georgopoulos C. The biology of heat shock proteins and molecular chaperones. Plainview: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen SP, Gonzalez-Alonso J, Nielsen J-J, Saltin B, Hellsten Y. Muscle interstitial ATP and norepinephrine concentrations in the human leg during exercise and ATP infusion. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1757–1762. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00638.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen B, Hyldig T, Bidstrup F, González-Alonso J, Christoffersen GR. Brain activity and fatigue during prolonged exercise in the heat. Pflügers Arch - Eur J Physiol. 2001;442:41–48. doi: 10.1007/s004240100515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njemini R, Lambert M, Demanet C, Mets T. Elevated serum heat-shock protein 70 levels in patients with acute infection: use of an optimized enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Scand J Immunol. 2003;58:664–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2003.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njemini R, Demanet C, Mets T. Inflammatory status as an important determinant of heat shock protein 70 serum concentrations during aging. Biogerontology. 2004;5:31–38. doi: 10.1023/B:BGEN.0000017684.15626.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble EG, Milne KJ, Melling CW. Heat shock proteins and exercise: a primer. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33:1050–1065. doi: 10.1139/H08-069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybo L, Nielsen B. Perceived exertion is associated with an altered brain activity during exercise with progressive hyperthermia. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:2017–2023. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.5.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa F, Shimizu K, Hara T, Muroi E, Hasegawa M, Takehara K, Sato S. Serum levels of heat shock protein 70, a biomarker of cellular stress, are elevated in patients with systemic sclerosis: association with fibrosis and vascular damage. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26:659–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa K, Seta R, Shimizu T, Shinkai S, Calderwood SK, Nakazato K, Takahashi K. Plasma adenosine triphosphate and heat shock protein 72 concentrations after aerobic and eccentric exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2011;17:136–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Périard JD, Caillaud C, Thompson MW. Central and peripheral fatigue during passive and exercise-induced hyperthermia. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1657–1665. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182148a9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Périard JD, Caillaud C, Thompson MW (2011b) The role of aerobic fitness and exercise intensity on endurance performance in uncompensable heat stress conditions. Eur J Appl Physiol. doi:10.1007/s00421-00011-02165-z [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pockley AG, Shepherd J, Corton JM. Detection of heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) and anti-Hsp70 antibodies in the serum of normal individuals. Immunol Invest. 1998;27:367–377. doi: 10.3109/08820139809022710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pockley AG, Georgiades A, Thulin T, Faire U, Frostegård J. Serum Heat Shock Protein 70 Levels Predict the Development of Atherosclerosis in Subjects With Established Hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;42:235–238. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000086522.13672.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugh LGCE, Corbett JL, Johnson RH. Rectal temperatures, weight losses, and sweat rates in marathon running. J Appl Physiol. 1967;23:347–352. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.23.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruell PA, Thompson MW, Hoffman KM, Brotherhood JR, Richards DA. Plasma Hsp72 is higher in runners with more serious symptoms of exertional heat illness. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;97:732–736. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger MJ. Heat shock proteins. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:12111–12114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkirk GA, McLellan TM, Wright HE, Rhind SG. Expression of intracellular cytokines, HSP72, and apoptosis in monocyte subsets during exertional heat stress in trained and untrained individuals. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R575–R586. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90683.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh RC, Koukoulas I, Garnham A, Moseley PL, Hargreaves M, Febbraio MA. Exercise increases serum Hsp72 in humans. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:386–393. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0386:EISHIH>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch WJ. Mammalian stress response: cell physiology, structure/function of stress proteins, and implications for medicine and disease. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:1063–1081. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C. Heat Shock Transcription Factors: structure and regulation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:441–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada P, Amorim F, Moseley P, Schneider S. Heat shock protein 72 response to exercise in humans. Sports Med. 2008;38:715–733. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200838090-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler TR, Ogden LG, Singleton KD, Luo M, Fernandez-Estivariz C, Griffith DP, Galloway JR, Wischmeyer PE. Parenteral glutamine increases serum heat shock protein 70 in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1079–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]