Abstract

As an initial step in the development of a bone tissue engineering strategy to rationally control inflammation, we investigated the interplay of bone-like extracellular matrix (ECM) and varying doses of the inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) on osteogenically differentiating mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) cultured in vitro on 3D poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) microfiber scaffolds containing pregenerated bone-like ECM. To generate the ECM, PCL scaffolds were seeded with MSCs and cultured in medium containing the typically required osteogenic supplement dexamethasone. However, since dexamethasone antagonizes TNF-α, the interplay of ECM and TNF-α was investigated by culturing naïve MSCs on the decellularized scaffolds in the absence of dexamethasone. MSCs cultured on ECM-coated scaffolds continued to deposit mineralized matrix, a late stage marker of osteogenic differentiation. Mineralized matrix deposition was not adversely affected by exposure to TNF-α for 4–8 days, but was significantly reduced after continuous exposure to TNF-α over 16 days, which simulates the in vivo response, where brief TNF-α signaling stimulates bone regeneration, while prolonged exposure has damaging effects. This underscores the exciting potential of PCL/ECM constructs as a more clinically realistic in vitro culture model to facilitate the design of new bone tissue engineering strategies that rationally control inflammation to promote regeneration.

Keywords: bone tissue engineering scaffold, extracellular matrix, mesenchymal stem cells, osteogenesis, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Inflammation is an immediate response to bone injury, and a growing body of evidence indicates that the signaling cascades initiated during the week-long acute inflammatory response play a critical role in priming bone regeneration.1–3 Bone fracture alters the expression of over 6000 genes, including genes encoding inflammatory cytokines as well as a variety of growth factors.4 Together with growth factors, fracture-induced inflammatory mediators promote regeneration, e.g., by promoting angiogenesis and guiding mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) differentiation.1–3 Several cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1), have been shown to directly modulate the migration of MSCs in vivo.5–8

Further studies into the impact of TNF-α on MSC osteogenic differentiation have been motivated by the recognition of its important role during in vivo bone regeneration. TNF-α expression increases immediately after bone injury, returning to baseline after a few days, and is elevated again in later stages of bone remodeling.9–11 In an animal model lacking TNF-α, fracture healing was severely impaired and bone formation was delayed by several weeks.12,13 In an in vivo fracture healing model, repeated local injections of TNF-α in the first few days after injury resulted in significantly increased fracture callus mineralization four weeks later.8

While exciting, these results have also highlighted the need for more realistic in vitro models of the fracture healing environment. In vitro studies of the effects of TNF-α on osteogenic differentiation have been complicated by the fact that two supplements typically used to stimulate in vitro MSC osteogenic differentiation, dexamethasone and ascorbic acid, antagonize TNF-α signaling.14–16 In fact, when added to this typical osteogenic medium, TNF-α had the opposite effect of that seen in vivo; it suppressed in vitro MSC osteogenic differentiation.17,18 One strategy to overcome this limitation has been to preculture MSCs in osteogenic supplements and then administer TNF-α afterwards. In the absence of dexamethasone, TNF-α has been shown to stimulate dose-dependent increases in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and mineralized matrix deposition, which are, respectively, early and late markers of osteogenesis.8,14,19–21

In a continued effort to better model the function of TNF-α in the fracture healing microenvironment, this study investigated the interplay of bone-like extracellular matrix (ECM) and TNF-α on MSC osteogenic differentiation. Although the bone ECM is mainly composed of mineralized deposits, the fracture microenvironment contains a hematoma rich in molecular signaling sources including: insoluble macromolecules (e.g., collagen), soluble proteins (including growth factors and cytokines), as well as proteins and receptors on the surfaces of neighboring cells.2,22 Our laboratory has previously described a method to coat microfiber meshes with bone-like, mineralized ECM containing an array of osteogenic growth factors.23–25 The presence of preformed bone-like ECM has been shown to transform osteoconductive microfiber scaffolds into osteoinductive materials.24–28

To create a more realistic in vitro model of the injured bone microenvironment and to elucidate the interplay of TNF-α and bone-like ECM, this study investigated the impact of varying doses of TNF-α delivered to osteogenically differentiating MSCs cultured on 3D biodegradable microfiber scaffolds containing pregenerated bone-like ECM (PCL/ECM). The objective of this study was to determine the impact of bone-like ECM on the concentration of TNF-α which enhances in vitro osteogenic differentiation of MSCs.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Experimental design

The study design required the culture of two separate batches of MSCs on each electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) scaffold: one batch to generate the bone-like ECM, and a second batch for the actual experiment (Figure 1). A design with 7 groups and 3 time points was used to evaluate the interplay of pregenerated bone-like ECM and varying TNF-α concentration on rat MSC osteogenic differentiation (Figure 2). The three experimental groups received identical concentrations of TNF-α (0.1 ng/mL, 5 ng/mL, 50 ng/mL) to those used in a previous study of MSC in vitro osteogenic differentiation on plain PCL scaffolds.14 This facilitated evaluation of the interplay of pregenerated ECM and TNF-α. Four control groups were included: a positive control seeded with MSCs precultured in dexamethasone-replete (+dex) osteogenic media that continued to be supplemented with dexamethasone during the study; two negative controls cultured in dexamethasone-free (−dex) media that differed in terms of the MSCs seeded (one group had MSCs precultured in +dex osteogenic media and the other had MSCs precultured in −dex media); and a group of acellular PCL/ECM scaffolds that were “cultured” in −dex media. This final group was included because similar ECM-coated scaffolds have been previously shown to undergo non-cell-specific scaffold calcium accumulation.27

Figure 1.

Overall study design using pregenerated bone-like ECM. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) were isolated from rat bone marrow and cultured on electrospun PCL scaffolds in the presence of dexamethasone (+dex) and complete osteogenic media, which has been shown to stimulate production of bone-like ECM. These MSCs were removed and then replaced with a second batch of freshly isolated MSCs, which were subjected to the experimental conditions shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic of study design for ECM and TNF-α interplay. The four control groups consist of two negative controls seeded with MSCs precultured in “+dex” media (as shown) or in “−dex” media; a positive control seeded with MSCs precultured in “+dex” media that continued to receive dexamethasone during days 0–16, and a group of acellular PCL/ECM scaffolds. OM = Osteogenic Media (α-MEM, 10% v/v fetal bovine serum, 50 μg gentamicin/mL, 0.5 μg amphotericin-B/mL, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid) either with or without 10−8 M dexamethasone (“+dex” vs. “−dex”).

Electrospun PCL preparation

Electrospun PCL meshes were generated according to an established protocol.14 The PCL (Lactel, Pelham, AL) had a number-average molecular weight (Mn) of 59,000 ± 800 Da and polydispersity index (Mw/Mn) of 2.01 ± 0.03, determined via gel permeation chromatography (Phenogel Linear Column with 5 μm particles, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA; Differential Refractometer 410, Waters, Milford, MA) and a calibration curve generated from polystyrene standards (Fluka, Switzerland). A 10 mL syringe was loaded with an 18 w/w% solution of PCL in 5:1 (by vol) chloroform:methanol, fitted with a 16 gauge blunt-tip needle (Brico Medical Supplies, Inc., Metuchen, NJ), and positioned in the electrospinning apparatus so that the needle tip was 33 cm from a glass collecting plate placed over the system’s grounded copper plate. A detailed description of this electrospinning apparatus has been published previously.14,29 A voltage difference of 33 kV was applied to the needle tip and to a copper ring placed 4 cm from the needle tip. The PCL solution was pumped out of the needle at 40 mL/h using a syringe pump until an electrospun mesh of ~1mm thickness was generated on the glass collecting plate. All scaffolds used in this study were derived from two electrospun meshes.

Scaffolds with 8 mm diameter were cut from the meshes using biopsy punches (Miltex, York, PA). The thickness of each scaffold was measured using digital micro-calipers (Mitutoyo, Aurora, IL) and, to maintain consistency with previous work14, scaffolds with thickness 0.90–1.10 mm were used for the study. To prevent degradation or changes to the scaffold surface, electrospinning was performed two days prior to MSC seeding, which allowed just enough time to sterilize and prewet the scaffolds.

Scaffold characterization

Scaffolds (n = 3) from each of the two electrospun meshes used in this study were mounted onto aluminum stubs, sputter-coated with 20 nm of platinum, and imaged using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (FEI Quanta 400 Environmental, Hillsboro, OR) at a 7.0 kV accelerating voltage and 2.5 spot size. Predefined coordinates on each scaffold were imaged and the diameters of (n = 45 fibers) from the top and (n = 45 fibers) from the bottom of each mesh were measured using an established protocol.14,29. The porosity of n = 50 scaffolds from each mesh was determined via an established gravimetric analysis protocol.14,29

Preparation of ECM-coated PCL scaffolds

All MSC isolations were approved by the Rice University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines (NIH Publication #85-23 Rev. 1985) for the care and use of laboratory animals. Two batches of cells were required for this study (see Figure 1) and were obtained from separate MSC isolations. MSCs were isolated from the pooled femoral and tibial bone marrow of syngeneic male Fischer 344 rats weighing 150–175 g, according to established methods.25,30 The MSCs from the first isolation (n = 8 rats) were used to generate the bone-like ECM. The bone marrow suspensions from this isolation were cultured in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks using complete (+dex) osteogenic media, which consisted of α-MEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA), 50 μg/mL gentamicin, 0.5 μg/mL amphotericin-B, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, and 10−8 M dexamethasone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The medium was changed after one day and the non-adherent cells removed. The adherent cells were designated as “mesenchymal stem cells,” based on the established osteogenic potential of this cell population under appropriate in vitro conditions.14,31,32 Thereafter, media was changed every two days. MSCs were cultured for a total of 7 days until nearly confluent and then seeded onto PCL scaffolds.

Prior to MSC seeding, and immediately after being punched from freshly electrospun meshes, the PCL scaffolds were sterilized via exposure to ethylene oxide gas for 14h and prewet using a decreasing ethanol gradient (from 100% to 70%), according to established protocols.14,29 The ethanol was exchanged with sterile milliQ water, and then with sterile +dex media. The scaffolds were stored in +dex medium at 37°C overnight. The next day, the scaffolds were press-fit into sterile seeding cassettes and placed into ultra-low attachment 6-well plates (1 cassette/well) (Corning Incorporated Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) for seeding.

On the day of seeding, the nearly confluent MSCs were detached with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), counted with a hemocytometer, centrifuged, and resuspended at 1.25 million cells/mL in +dex osteogenic media. 0.2 mL of the resuspended MSCs were added drop-wise to each seeding cassette containing a press-fit scaffold. After a 4h attachment period, each well was filled with 8 mL of +dex media. After 24h, the constructs were moved to fresh ultra-low attachment 6 well plates containing 4 mL of fresh +dex media (1 scaffold/well). The constructs were cultured for 12 days total, with media changes every two days.

Decellularization of PCL/ECM

After 12 days, all scaffolds were removed from the media and rinsed twice with 4 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). For baseline calcium measurements, (n = 4) constructs were each placed into 1 mL of sterile milliQ water and flash-frozen. These constructs were stored at −20°C in a non-defrosting freezer until the day 4 timepoint, when they were decellularized and their calcium content was quantified in parallel to that of the day 4 samples. The remaining constructs were immediately decellularized according to an established protocol25 to create the PCL/ECM scaffolds that were used for the experiment. Briefly, the scaffolds were placed in 1.5 mL sterile milliQ water, flash-frozen, and stored at −20°C overnight. The next day, the scaffolds were thawed at 37°C for 10 min, rinsed twice with 2 mL PBS, and then placed in 1.5 mL fresh sterile milliQ water. Aseptic techniques were used for all steps. Using liquid nitrogen for 10 min to complete the freeze step, the entire freeze/thaw (37°C for 10 min)/rinse cycle was repeated two more times, and then the decellularized PCL/ECM scaffolds were press-fit into sterile seeding cassettes. Each seeding cassette was placed into the well of a sterile ultra-low attachment 6-well plate (1 cassette/well) for MSC seeding.

MSC isolation for TNF-α culture

On the sixth day of ECM pregeneration, a new batch of MSCs were isolated from the pooled femoral and tibial bone marrow of (n = 6) male syngeneic Fischer 344 rats weighing 150–175 g, according to established methods.25,30 The bone marrow suspensions from each rat were split into two portions and cultured in either +dex or −dex media in 75 cm2 culture flasks. As in the previous isolation, non-adherent cells were removed after 24h and the MSCs were cultured for 7 days total.

On the day of seeding, which was the same day that the decellularized PCL/ECM scaffolds were prepared, the nearly confluent MSCs were detached with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Gibco), counted with a hemocytometer, centrifuged, and resuspended at 1.25 million cells/mL in −dex osteogenic media. The cells that had been precultured in −dex media were lifted and resuspended separately from those precultured in +dex media. For the MSCs precultured in −dex media, 0.2 mL of the cell suspension were added to (n = 13) PCL/ECM scaffolds; this was the −dex/−dex control group (see Figure 2). For the acellular group, (n = 13) PCL/ECM scaffolds were press-fit into seeding cassettes but were not seeded with any MSCs. The remaining PCL/ECM scaffolds were seeded with +dex-precultured cells (0.2 mL cell suspension/scaffold, corresponding to 0.25 million cells/scaffold). After allowing 4h for cell attachment, each well was filled with 8 mL of −dex media and the relevant groups (see Figure 2) were supplemented with either dexamethasone (to achieve a 10−8 M concentration) or 4 μL/well of the appropriate TNF-α stock solution.

TNF-α reconstitution and dilution

On the day of scaffold seeding, recombinant rat TNF-α (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions using sterile PBS containing 0.1 w/w% bovine serum albumin (Sigma). This 100 ng/μL stock solution was then further diluted to prepare 0.1 ng/μL, 5 ng/μL, and 50 ng/μL stock solutions. For experiments, 4 μL of TNF-α stock solution were added to 4 mL of media used for construct culture, resulting in the desired 0.1 ng/mL, 5 ng/mL, or 50 ng/mL TNF-α.

Biochemical assays for cellularity, alkaline phosphatase activity, and calcium content

On days 4, 8, and 16 of the culture of the second batch of MSCs on PCL/ECM (see Figure 1), (n = 4) scaffolds from each group were removed, rinsed twice with 4 mL of PBS, and flash-frozen in 1 mL of sterile milliQ water using liquid nitrogen. The cells were lysed using three consecutive freeze/thaw/sonication cycles (10 min at −80°C, 10 min at 37°C, 10 min sonication). The DNA content of each resulting cell lysate was quantified using the fluorometric PicoGreen assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and then converted to the number of cells per construct.14,25 The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity of the cell lysates was quantified using an established colorimeteric assay based on the rate of conversion of the colorless substrate, p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt hexahydrate (Sigma), to a yellow product, p-nitrophenol.14,25 Next, each construct was transferred into 1 mL of 1 N acetic acid and left on a shaker table at 200 rpm overnight to dissolve the matrix-bound calcium. Calcium content was quantified using an established colorimetric assay based on the Arsenazo III calcium chelating agent (Genzyme Diagnostics PEI, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, Canada).14,25 Samples and standards were run in triplicate for all assays. Samples were diluted as necessary to fall within the range of the standards for each assay.

Sample preparation for histology and SEM

At the final timepoint, n = 1 construct from each of the seven groups was rinsed twice with PBS and cut in half with a sterile razorblade. One half of each construct was prepared for SEM via fixation in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma) overnight and then dehydration through an ascending ethanol gradient (70% to 100%). The samples were air-dried overnight, mounted on aluminum stubs, coated with platinum, and imaged via SEM as described above. The other half of each construct was fixed overnight in 5 mL of 10% buffered formalin phosphate (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), passed through an ascending ethanol gradient (70% to 100%), and then embedded in HistoPrep (Fisher Scientific) overnight at room temperature. Frozen 5 μm thick sections were cut with a cryotome (CM1850, Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL), placed on Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific), and incubated at 45°C on a slide warmer for 4–5 days to achieve optimal section adhesion.14

On the day of histological staining, the sections were rehydrated with water. The slides were then flooded with von Kossa stain (5 w/w% silver nitrate (Sigma) in milliQ water) and kept under an ultraviolet (UV) lamp for 30 min. The slides were rinsed with water and then 95% ethanol. Alcoholic eosin Y (Sigma) was applied as a counter-stain for 3 min. The slides were rapidly dehydrated and cleared with 95% ethanol, and then imaged with a light microscope (Eclipse E600, Nikon, Melville, NY) equipped with a camera (3CCD Color Video Camera DXC-950P, Sony, Park Ridge, NJ) and image-capture software. Light microscope images were calibrated using the standard two-image method to correct for differences in background lighting and in dark-current effects in the detector.33

Statistical analysis

Fiber diameters and porosities are reported as mean ± standard deviation for n = 45 fibers and n = 50 scaffolds, respectively. The average fiber diameter of the top and bottom of each PCL microfiber mesh, along with the average porosity, were compared using a Student’s t-test for two independent samples with equal variance (α = 0.05) after performing an F-test to validate the assumption of equal variance at 95% confidence. Cellularity, ALP activity, and calcium assay results are reported as mean ± standard deviation for n = 4 constructs. Statistical differences amongst groups at each time point, and also within each group over time, were analyzed at 95% confidence using one-way analysis of variance. Multiple pair-wise comparisons were made using the Bonferroni post-hoc analysis method at 95% confidence.

RESULTS

Electrospun PCL morphology

The morphology of representative scaffolds is shown in Figure 3, imaged via SEM at varying magnifications. As shown in Table 1, one mesh had a slightly higher mean fiber diameter at the bottom (~14 μm), but this did not affect MSC culture since the top surfaces of the scaffolds were seeded with MSCs. The top surfaces of the PCL microfiber meshes had statistically equivalent mean fiber diameters (p > 0.05), as shown in Table 1. Additionally, the two electrospun PCL microfiber meshes fabricated for this study had statistically equivalent mean porosities (p > 0.05) (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Representative scaffold morphology via SEM. Representative scaffolds from the electrospun PCL meshes generated for this study, imaged via SEM at varying magnifications, (a) 300×, (b) 600×, and (c) 2000×. Scale bar for (a) is 200 μm, for (b) is 100 μm, and for (c) is 25 μm.

Table 1.

Comparison of fiber diameters and porosites for the two electrospun meshes used for this study

| Parameter for Comparison | Value for Mesh 1 | Value for Mesh 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Fiber Diameter, Top (μm) | 10.9 ± 2.0 | 11.8 ± 1.2 |

| Fiber Diameter, Bottom (μm) | 11.3 ± 1.4* | 13.6 ± 2.4* |

| Porosity (%) | 80.6 ± 2.1 | 80.1 ± 2.0 |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation. The sample size was n = 45 for fiber diameters from the top and bottom of each mesh, and n = 50 scaffolds for PCL mesh porosity.

indicates pairs of values that significantly differ (p < 0.05). Note that MSCs were seeded on the top surface of each scaffold, so differences in the bottom fiber diameter were unlikely to affect MSC culture.

PCL/ECM construct cellularity

Figure 4 depicts the construct cellularity at each timepoint. Overall, the cellularity of the groups at each timepoint was fairly similar. As expected, the acellular PCL/ECM constructs (“Acellular”) had nearly zero cells at all timepoints. The cellularity of all the other groups, with the exception of those exposed to the intermediate and high doses of TNF-α (“5 ng/mL TNF” and “50 ng/mL TNF,” respectively), showed a slight peak at day 8. However, only the positive control group (“0 ng/mL TNF +dex”) had statistically unique cellularity at each timepoint (p < 0.05). The positive control group and the dexamethasone-naïve negative control group (“0 ng/mL TNF (pre: −dex)”) had lower cell content than all other groups (except the acellular constructs) on days 8 and 16 (p < 0.05). The low-dose TNF-α group (“0.1 ng/mL TNF”) and the +dex-precultured negative control group (“0 ng/mL TNF”) had equivalent cell content on day 16 (p > 0.05), while the 5 ng/mL TNF and 50 ng/mL TNF groups had significantly higher (p < 0.05) cellularity than all other groups on day 16. The intermediate and high doses of TNF-α induced cell proliferation, so that the day 16 values significantly exceeded (p < 0.05) the day 4 values.

Figure 4.

MSC cell count on preformed ECM with varying TNF-α dose. Scaffolds with pregenerated bone-like ECM (PCL/ECM) were seeded with MSCs precultured in +dex media (except for the group designated “(pre: −dex),” which was seeded with MSCs precultured in −dex media). Experimental groups were exposed to varying TNF-α doses. The control groups included acellular PCL/ECM, a positive control cultured in +dex media (0 ng/mL +dex), and two negative controls cultured in −dex media (0 ng/mL TNF) containing MSCs precultured in either +dex or −dex media (the latter is denoted with “pre: −dex”). Bars represent average ± standard deviation of (n = 4) scaffolds per group at each timepoint. Within a timepoint, groups with * differ from all other groups (p < 0.05), while letters A–D indicate groups that differ from all other groups but not groups with the same letter (p < 0.05). On day 16, + indicates that d4 and d16 values of that group differ (p < 0.05), while # indicates that values at all timepoints differ (p < 0.05).

PCL/ECM construct ALP activity

Figure 5 depicts the ALP activity of the constructs at each timepoint. Figure 5a depicts the ALP activity on a per scaffold basis, and was included because the acellular PCL/ECM constructs had non-zero ALP activity. At day 4, the acellular group had significantly lower ALP activity than all other groups (p < 0.05), but on days 8 and 16, the values for this group were equivalent to those of the 5 ng/mL TNF and 50 ng/mL TNF groups (p > 0.05). The ALP activity on a per cell basis is shown in Figure 5b for all groups except for the acellular constructs. In contrast to the other groups, the ALP activity (per cell) of the 0 ng/mL +dex positive control group showed a monotonic increase over time such that the value at each timepoint was statistically unique (p < 0.05). On days 8 and 16, the ALP activity of this group was much higher (p < 0.05) than that of all other groups. TNF-α suppressed ALP activity at all timepoints. The 5 ng/mL TNF and 50 ng/mL TNF had significantly lower ALP activity (per cell) than all other groups (p < 0.05) at all timepoints. The 0.1 ng/mL TNF group had significantly lower ALP activity per cell (p < 0.05) than the corresponding negative control (0 ng/mL TNF) on days 4 and 16, and had equivalent ALP activity (p > 0.05) to the dexamethasone-naïve negative control (0 ng/mL TNF (pre: −dex)) on days 8 and 16.

Figure 5.

ALP activity of MSCs on preformed ECM with varying TNF-α dose. Scaffolds with pregenerated bone-like ECM (PCL/ECM) were seeded with MSCs precultured in +dex media (except for the group designated “(pre: −dex),” which was seeded with MSCs precultured in −dex media). ALP activity on a per scaffold basis is shown in (a), while the same data on a per cell basis is shown in (b) with the exception of the acellular group. Experimental groups were exposed to varying TNF-α doses. The control groups included acellular PCL/ECM, a positive control cultured in +dex media (0 ng/mL +dex), and two negative controls cultured in −dex media (0 ng/mL TNF) containing MSCs precultured in either +dex or −dex media (the latter is denoted with “pre: −dex”). Bars represent average ± standard deviation of (n = 4) scaffolds per group at each timepoint. Within a timepoint, groups with * differ from all other groups (p < 0.05), while letters A–F indicate groups that differ from all other groups but not groups with the same letter (p < 0.05). On day 16, + indicates that d4 and d16 values of that group differ (p < 0.05), while # indicates that values at all timepoints differ (p < 0.05).

PCL/ECM construct mineralization

The baseline calcium content of the PCL/ECM was 140 ± 13 μg Ca2+/scaffold, which is indicated by the dashed line in Figure 6. The acellular PCL/ECM constructs accumulated calcium at a rapid, linear rate (~23 μg/day). All groups had statistically equivalent calcium content on day 4 (p > 0.05). On day 8, the dexamethasone-naïve negative control (0 ng/mL TNF (pre: −dex) and 0.1 ng/mL TNF groups had significantly lower calcium content than all other groups (p < 0.05). On day 16, the dexamethasone-naïve negative control again had the lowest calcium content (p < 0.05). In contrast, the 0 ng/mL +dex positive control had the highest calcium content on day 16 (p < 0.05), followed by the +dex-precultured 0 ng/mL TNF negative control. Comparing the experimental groups to this negative control indicates that TNF-α suppressed day 16 mineralization in a dose-dependent fashion.

Figure 6.

MSC calcium deposition on PCL/ECM with varying TNF-α dose. The baseline calcium content of the PCL scaffolds with pregenerated bone-like ECM (PCL/ECM) was 140 ± 13 μg Ca2+/scaffold, which is indicated by the dashed line. PCL/ECM scaffolds were seeded with MSCs precultured in +dex media (except for the group designated “(pre: −dex),” which was seeded with MSCs precultured in −dex media). Experimental groups were exposed to varying TNF-α doses. The control groups included acellular PCL/ECM, a positive control cultured in +dex media (0 ng/mL +dex), and two negative controls cultured in −dex media (0 ng/mL TNF) containing MSCs precultured in either +dex or −dex media (the latter is denoted with “pre: −dex”). Bars represent average ± standard deviation of (n = 4) scaffolds per group at each timepoint. Within a timepoint, groups with * differ from all other groups (p < 0.05), while letters A–C indicate groups that differ from all other groups but not groups with the same letter (p < 0.05). On day 16, + indicates that d4 and d16 values of that group differ (p < 0.05), while # indicates that values at all timepoints differ (p < 0.05).

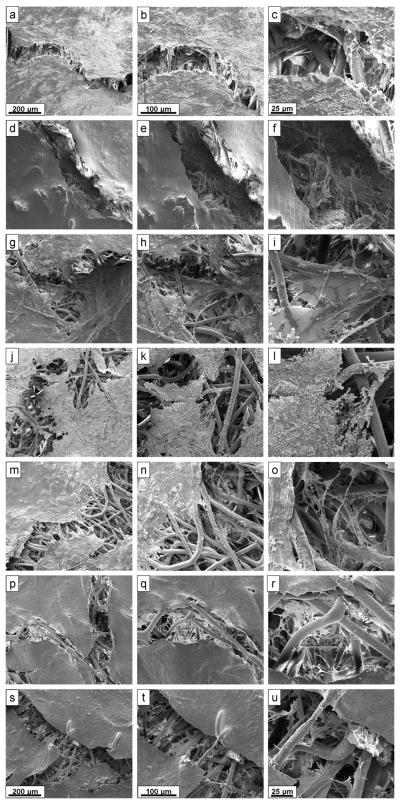

Day 16 construct morphology

SEM imaging (Figure 7) and histology (Figure 8) confirmed that cells and matrix coated the surfaces of the scaffolds and also penetrated into the pores between the PCL fibers. Histological sections (Figure 8) were stained with von Kossa, which stains mineralized ECM black (blue arrows), and counter-stained with eosin, which stains cytoplasmic material and organic ECM components (e.g., collagen) reddish-pink (yellow arrows). Histological analysis qualitatively confirmed the results of the cellularity (Figure 4) and calcium content (Figure 6) assays. For example, the 0 ng/mL +dex positive control was the darkest-staining group, consistent with the calcium assay data, and had few identifiable pink-stained cells, consistent with the cellularity results. Although the highest density of mineralized matrix (blue arrows) and cells (yellow arrows) occurred at the top of the scaffolds, cells and small mineralized deposits were observed 200–500 μm below the surface. Lower density collections of cells within the scaffolds appear as grayish threads spanning between the PCL fibers, which is an artifact of the low magnification (10×) used to capture the images; at higher magnification, these features were pink in color, as expected.

Figure 7.

Surface morphology of PCL/ECM after 16 days of culture. On the final day of the study, the surface of one half of a representative scaffold from each group was imaged via SEM. Images in each row are from the same group, and images in each column have the same magnification. Specifically, the images depict: (a–c) the positive control (0 ng/mL +dex in other Figures); (d–f) the negative control cultured in −dex media (0 ng/mL TNF); (g–i) the negative control seeded with dexamethasone-naïve MSCs and cultured in −dex media (0 ng/mL TNF (pre: −dex)); and (j–l) acellular PCL/ECM (Acellular). The final three rows of images depict the experimental groups cultured with varying doses of TNF-α: (m–o) 0.1 ng/mL, (p–r) 5 ng/mL, and (s–u) 50 ng/mL. The original magnification of the images in the columns (from left to right) is: 200× (scale bar is 200 μm), 400× (scale bar is 100 μm), 1000× (scale bar is 25 μm). For all columns, the scale bars at the top and bottom of each column apply to all images within that column.

Figure 8.

PCL/ECM construct cell and mineral distribution visualized by histology after 16 days of culture (cross-sectional view). Group names are the same as previous figures. 5 μm thick sections were stained with von Kossa, which stains mineralized matrix black (blue arrows), and eosin, which stains cells and non-mineralized matrix reddish-pink (yellow arrows). Images were captured at 10× original magnification. Scale bar in the lower right corner represents 200 μm and applies to all images.

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to determine the interplay of TNF-α and pregenerated bone-like ECM on the in vitro osteogenic differentiation of MSCs. The experimental design (Figure 2) was nearly identical to a previous study14 that examined the impact of varying TNF-α dose on the in vitro osteogenic differentiation of MSCs cultured on plain electrospun PCL scaffolds (i.e., lacking pregenerated ECM). Comparison to these previously published results indicates that pregenerated bone-like ECM had a significant interplay with TNF-α in terms of cellularity, ALP activity, and, most notably, mineralized matrix deposition.

The lowest TNF-α concentration (0.1 ng/mL) used in this study was equivalent to that measured in wound fluid from patients with severe bone injuries.34 In comparison to the cellularity results on plain PCL,14 the presence of bone-like ECM suppressed the proliferation of the 0.1 ng/mL TNF group and stimulated proliferation of the 5 and 50 ng/mL TNF groups (Figure 4). The cellularity of the control groups was similar on both plain PCL and PCL/ECM.

The presence of preformed ECM greatly increased the ALP activity (Figure 5) of all groups by several fold compared to plain PCL. The most prominent change was in the acellular constructs, which had negligible ALP activity in the previous study on plain PCL meshes,14 but had significant ALP activity on PCL/ECM (Figure 5a) despite near-zero cellularity (Figure 4). The ALP activity detected for the acellular PCL/ECM constructs likely reflects ALP secreted by the first batch of MSCs, which generated the ECM. Studies of native rat bone have shown that ALP exists in both a membrane-bound form, on the external surface of osteoblasts, and also as a free extracellular enzyme localized near the collagen fibers of mineralizing osteoid.35 It is likely that the values for the acellular PCL/ECM constructs reflect the activity of this latter “free” ALP, since nearly complete decellularization of the PCL/ECM was achieved (Figure 4). Aside from the change in the magnitude of the ALP activity values, the trends observed for the control and experimental groups in this study (Figure 5) were similar to those reported for plain PCL.14 For instance, the 5 and 50 ng/mL TNF groups showed a monotonic decrease in ALP activity in both cases. On days 8 and 16, the ALP activity per scaffold for these groups was indistinguishable from that of the acellular constructs (Figure 5a), suggesting that the increased ALP values on PCL/ECM were due to the extracellular ALP, which was not affected by TNF-α.

The presence of pregenerated ECM caused the acellular PCL/ECM constructs to accumulate calcium at a rapid, linear rate (~23 μg/day). This phenomenon has been previously reported for PCL microfiber scaffolds with smaller fiber diameter (~5 μm, compared to ~10 μm in this study) that were coated with ECM generated under similar in vitro culture conditions.27 Remarkably, despite the presence of ECM, the dexamethasone-naïve negative control group (0 ng/mL TNF (pre: −dex)) ceased to mineralize between days 4 and 8 (Figure 6). Although some calcium deposition occurred between days 8 and 16, this group had the lowest calcium content at the final timepoint (p < 0.05). This type of negative control was not included in the previous study of PCL/ECM,27 which only included a negative control with MSCs precultured in +dex media (analogous to the “0 ng/mL TNF” group in Figure 6). The low calcium content of the “0 ng/mL TNF (pre: −dex)” negative control indicates that the presence of dexamethasone-naïve cells and/or the ECM secreted by these cells inhibited the non-cell-specific calcium accumulation of the pregenerated ECM. Thus, the dexamethasone-naïve MSC-seeded PCL/ECM constructs may be a superior negative control compared to acellular PCL/ECM, since all other groups also contained cells, which would also presumably reduce non-cell-specific calcium accumulation.

As previously observed in a similar 3D culture system containing biodegradable microfibers coated with bone-like ECM 27, MSCs cultured on PCL/ECM continued to undergo osteogenic differentiation and deposit mineralized matrix in the absence of dexamethasone. This is remarkable because dexamethasone is typically required for in vitro osteogenic differentiation of MSCs.36 However, since corticosteroid signaling is not involved in in vivo bone regeneration, and may even inhibit fracture healing,1,37 our findings suggest that culture on 3D PCL/ECM constructs is a better model of in vivo MSC osteogenic differentiation.

The difference between TNF-α effect on MSCs cultured on plain PCL and on PCL/ECM constructs was most evident at the final timepoint. The highest dose of TNF-α stimulated mineralized matrix deposition on plain PCL.14 In contrast, TNF-α caused a dose-dependent decrease in calcium content on PCL/ECM (p < 0.05; Figure 6). The dose-dependent decrease seen in this study differs from the results of previous studies of osteoprogenitors cultured in vitro and exposed to TNF-α in the absence of dexamethasone; in those studies, TNF-α stimulated a dose-dependent increase in mineralized matrix deposition 8,14,19–21. However, with the exception of the previous study from our group, in which MSCs were cultured on 3D plain PCL microfiber meshes,14 all of these other studies involved delivery of TNF-α to cells cultured in 2D.8,19–21 Thus, the effects noted in this study likely reflect the interplay of the 3D bone-like ECM and TNF-α.

The findings of this study with respect to TNF-α may be a reflection of the fact that PCL/ECM constructs are a more realistic model of the in vivo fracture microenvironment. Although TNF-α signaling is critical for in vivo bone regeneration,12 the distinct temporal pattern of its expression cannot be ignored. In murine models, TNF-α signaling peaks 24h following bone injury, returns to baseline levels after a few days, and then rises again several weeks later.9 In a recent study of a fracture healing model, daily local injections of TNF-α during the first two days after bone fracture significantly increased fracture callus mineralization four weeks later.8 However, chronic exposure to high levels of TNF-α has damaging effects on in vivo fracture healing, including decreased bone volume and reduced bone mechanical strength.38 The pattern of mineralized matrix deposition seen on PCL/ECM is consistent with these in vivo findings. At early timepoints, high doses of TNF-α did not adversely affect calcium content. However, 16 days of continuous TNF-α delivery caused a dose-dependent decrease in mineralized matrix deposition (Figure 6). These results for TNF-α highlight the exciting potential of PCL/ECM constructs as a more clinically realistic in vitro culture model to improve our understanding of the in vivo effects of various cytokines.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrated that continuous delivery of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α over 16 days reduces mineralized matrix deposition, a late stage marker of osteogenic differentiation, when delivered to MSCs cultured in 3D electrospun PCL microfiber meshes coated with pregenerated bone-like ECM (PCL/ECM). As previously observed in a similar 3D culture system, MSCs cultured on PCL/ECM continued to undergo osteogenic differentiation and deposit mineralized matrix in the absence of dexamethasone. Exposure to TNF-α for 4–8 days caused a dose dependent decrease in cell-specific ALP activity, which is an early marker of osteogenic differentiation, and did not adversely affect mineralized matrix deposition. However, continuous TNF-α delivery over 16 days markedly reduced calcium deposition compared to the untreated control group. These results simulate the in vivo response to TNF-α, where brief, highly regulated signaling stimulates bone regeneration, while prolonged signaling has damaging effects on bone. Thus, this study underscores the exciting potential of PCL/ECM constructs as a more clinically realistic in vitro culture model to improve our understanding of the impact of various cytokines on MSC osteogenic differentiation, which will ultimately facilitate the design of new tissue engineering strategies to rationally control inflammation and promote bone regeneration.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DE17441, R01 AR57083) (AGM). PMM was supported by a training fellowship from the NIH Biotechnology Training Program (NIH Grant No. 5 T32 GM008362-19).

Abbreviations

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- −dex

without dexamethasone as a culture supplement

- +dex

refers to the presence of 10−8 M dexamethasone

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- MSC

mesenchymal stem cell

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PCL

poly(ε-caprolactone)

- PCL/ECM

PCL scaffolds containing pregenerated bone-like ECM

- SDF-1

stromal cell-derived factor-1

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- UV

ultraviolet

Footnotes

No benefit of any kind will be received either directly or indirectly by the author(s).

References

- 1.Mountziaris PM, Spicer PP, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Harnessing and modulating inflammation in strategies for bone regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0182. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolar P, Schmidt-Bleek K, Schell H, Gaber T, Toben D, Schmidmaier G, Perka C, Buttgereit F, Duda GN. The early fracture hematoma and its potential role in fracture healing. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16(4):427–434. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2009.0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pape H-C, Marcucio R, Humphrey C, Colnot C, Knobe M, Harvey EJ. Trauma-induced inflammation and fracture healing. J Orthop Trauma. 2010;24(9):522–525. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181ed1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rundle CH, Wang H, Yu H, Chadwick RB, Davis EI, Wegedal JE, Lau K-HW, Mohan S, Ryaby JT, Baylink DJ. Microarray analysis of gene expression during the inflammation and endochondral bone formation stages of rat femur fracture repair. Bone. 2006;38:521–529. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitaori T, Ito H, Schwarz EM, Tsutsumi R, Yoshitomi H, Oishi S, Nakano M, Fujii N, Nagasawa T, Nakamura T. Stromal cell–derived factor 1/CXCR4 signaling is critical for the recruitment of mesenchymal stem cells to the fracture site during skeletal repair in a mouse model. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(3):813–823. doi: 10.1002/art.24330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thevenot PT, Nair AM, Shen J, Lotfi P, Ko C-Y, Tang L. The effect of incorporation of SDF-1[alpha] into PLGA scaffolds on stem cell recruitment and the inflammatory response. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):3997–4008. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bocker W, Docheva D, Prall W, Egea V, Pappou E, Rossmann O, Popov C, Mutschler W, Ries C, Schieker M. IKK-2 is required for TNF-α-induced invasion and proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells. J Mol Med. 2008;86(10):1183–1192. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glass GE, Chan JK, Freidin A, Feldmann M, Horwood NJ, Nanchahal J. TNF-α promotes fracture repair by augmenting the recruitment and differentiation of muscle-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(4):1585–1590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018501108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kon T, Cho T-J, Aizawa T, Yamazaki M, Nooh N, Graves DT, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Expression of osteoprotegerin, receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (osteoprotegrin ligand) and related pro-inflammatory cytokines during fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res. 2001;16(6):1004–1014. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerstenfeld LC, Cullinane DM, Barnes GL, Graves DT, Einhorn TA. Fracture healing as a post-natal developmental process: Molecular, spatial, and temporal aspects of its regulation. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:873–884. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mountziaris PM, Mikos AG. Modulation of the inflammatory response for enhanced bone tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2008;14(2):179–186. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2008.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerstenfeld LC, Cho T-J, Kon T, Aizawa T, Tsay A, Fitch J, Barnes GL, Graves DT, Einhorn TA. Impaired fracture healing in the absence of TNF-α signaling: The role of TNF-α in endochondral cartilage resorption. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18(9):1584–1592. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.9.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerstenfeld LC, Cho TJ, Kon T, Aizawa T, Cruceta J, Graves BD, Einhorn TA. Impaired intramembranous bone formation during bone repair in the absence of tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Cells Tissues Organs. 2001;169(3):285–294. doi: 10.1159/000047893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mountziaris PM, Tzouanas SN, Mikos AG. Dose effect of tumor necrosis factor-[alpha] on in vitro osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells on biodegradable polymeric microfiber scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2010;31(7):1666–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Balga R, Wetterwald A, Portenier J, Dolder S, Mueller C, Hofstetter W. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha: Alternative role as an inhibitor of osteoclast formation in vitro. Bone. 2006;39(2):325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iqbal J, Sun L, Kumar TR, Blair HC, Zaidi M. Follicle-stimulating hormone stimulates TNF production from immune cells to enhance osteoblast and osteoclast formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(40):14925–14930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606805103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacey DC, Simmons PJ, Graves SE, Hamilton JA. Proinflammatory cytokines inhibit osteogenic differentiation from stem cells: implications for bone repair during inflammation. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17(6):735–742. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin C-C, Metters AT, Anseth KS. Functional PEG-peptide hydrogels to modulate local inflammation induced by the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF[alpha] Biomaterials. 2009;30(28):4907–4914. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hess K, Ushmorov A, Fiedler J, Brenner RE, Wirth T. TNF[alpha] promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells by triggering the NF-[kappa]B signaling pathway. Bone. 2009;45(2):367–376. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.04.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ding J, Ghali O, Lencel P, Broux O, Chauveau C, Devedjian JC, Hardouin P, Magne D. TNF-[alpha] and IL-1[beta] inhibit RUNX2 and collagen expression but increase alkaline phosphatase activity and mineralization in human mesenchymal stem cells. Life Sci. 2009;84(15–16):499–504. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paula-Silva FWG, Ghosh A, Silva LAB, Kapila YL. TNF-{alpha} promotes an odontoblastic phenotype in dental pulp cells. J Dent Res. 2009;88(4):339–344. doi: 10.1177/0022034509334070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(1):47–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomes ME, Bossano CM, Johnston CM, Reis RL, Mikos AG. In vitro localization of bone growth factors in constructs of biodegradable scaffolds seeded with marrow stromal cells and cultured in a flow perfusion bioreactor. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(1):177–88. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Datta N, Pham QP, Sharma U, Sikavitsas VI, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. In vitro generated extracellular matrix and fluid shear stress synergistically enhance 3D osteoblastic differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(8):2488–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505661103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Datta N, Holtorf HL, Sikavitsas VI, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. Effect of bone extracellular matrix synthesized in vitro on the osteoblastic differentiation of marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26(9):971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pham QP, Kasper FK, Mistry AS, Sharma U, Yasko AW, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. Analysis of the osteoinductive capacity and angiogenicity of an in vitro generated extracellular matrix. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;88(2):295–303. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thibault RA, Baggett LS, Mikos AG, Kasper FK. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells on pregenerated extracellular matrix scaffolds in the absence of osteogenic cell culture supplements. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(2):431–440. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liao J, Guo X, Nelson D, Kasper FK, Mikos AG. Modulation of osteogenic properties of biodegradable polymer/extracellular matrix scaffolds generated with a flow perfusion bioreactor. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2386–2393. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pham QP, Sharma U, Mikos AG. Electrospun poly(epsilon-caprolactone) microfiber and multilayer nanofiber/microfiber scaffolds: characterization of scaffolds and measurement of cellular infiltration. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7(10):2796–805. doi: 10.1021/bm060680j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pham QP, Kasper FK, Baggett LS, Raphael RM, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. The influence of the in vitro generated bone-like extracellular matrix on osteoblastic gene expression of marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2008;29(18):2729–2739. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276(5309):71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE, Caplan AI, Bruder SP. Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J Cell Biochem. 1997;64:295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merchant FA, Periasamy A. Correction Using Calibration Images. In: Wu Q, Merchant FA, Castleman KR, editors. Microscope Image Processing. Burlington: Elsevier; 2008. p. 258. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pape H-C, Schmidt RE, Rice J, van Griensven M, das Gupta R, Krettek C, Tscherne H. Biochemical changes after trauma and skeletal surgery of the lower extremity: Quantification of the operative burden. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(10):3441–3448. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200010000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonucci E, Silvestrini G, Bianco P. Extracellular alkaline phosphatase activity in mineralizing matrices of cartilage and bone: ultrastructural localization using a cerium-based method. Histochemistry. 1992;97(4):323–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00270033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng SL, Yang JW, Rifas L, Zhang SF, Avioli LV. Differentiation of human bone marrow osteogenic stromal cells in vitro: induction of the osteoblast phenotype by dexamethasone. Endocrinology. 1994;134(1):277–286. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.1.8275945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber AJ, Li G, Kalak R, Street J, Buttgereit F, Dunstan CR, Seibel MJ, Zhou H. Osteoblast-targeted disruption of glucocorticoid signalling does not delay intramembranous bone healing. Steroids. 2010;75(3):282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo R, Yamashita M, Zhang Q, Zhou Q, Chen D, Reynolds DG, Awad HA, Yanoso L, Zhao L, Schwarz EM, et al. Ubiquitin ligase smurf1 mediates tumor necrosis factor-induced systemic bone loss by promoting proteasomal degradation of bone morphogenetic signaling proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(34):23084–23092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709848200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]