Abstract

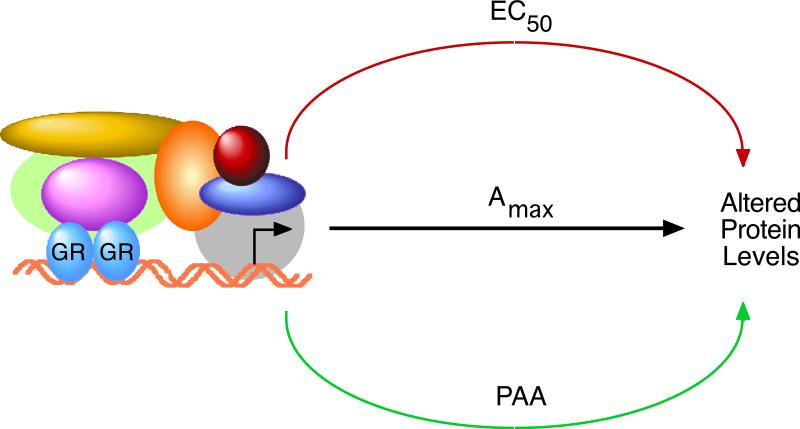

Increased specificity in steroid-regulated gene expression is a long-sought goal of endocrinologists. Considerable progress has resulted from the discovery of coactivators, corepressors, and comodulators that adjust the total activity (Amax) of gene induction. Two less frequently quantitated, but equally potent, means of improving specificity are the concentration of agonist steroid required for half-maximal activity (EC50) and the residual or partial agonist activity displayed by most antisteroids (PAA). It is usually assumed that the modulatory activity of transcriptional cofactors coordinately regulates Amax, EC50, and PAA. Here we examine the hypothesis that these three parameters can be independently modified by separate protein domains. The test system involves three differently sized fragments of each of three factors (glucocorticoid receptor [GR], coactivator TIF2, and comodulator STAMP), which are shown to form a ternary complex and similarly affect the induction properties of transfected and endogenous genes. Twenty five different fragment combinations of the ternary complex are examined for their ability to modulate the Amax, EC50, and PAA of a transiently transfected synthetic reporter gene. Different combinations selectively alter one, two, or all three parameters. These results clearly demonstrate that Amax, EC50, and PAA can be independently regulated under some conditions by different pathways or molecular interactions. This new mechanistic insight suggests that selected activities of individual transcription factors are attractive targets for small molecules, which would have obvious clinical applications for increasing the specificity of steroids during endocrine therapies.

Keywords: glucocorticoid receptors, dose-response curve, maximal induced activity, partial agonist activity, TIF2, STAMP

1. Introduction

A major objective in steroid hormone research has been to explain the selectivity of gene expression by steroids during development, differentiation, and homeostasis. The discovery of cognate receptor proteins for each class of steroid hormones, and the determination of their general mode of action, were great steps forward. Briefly, steroid binds to its intracellular receptor protein to give a complex that binds to specific genomic sequences, called hormone response elements (HREs), and recruits a variety of cofactors that regulate the rate of gene transcription with or without prior chromatin remodeling (Metivier et al., 2006, Lonard and O'Malley, 2007, Wu and Zhang, 2009). However, this model predicts that the affinity of steroid binding to its cognate receptor is the determining step, such that all regulated genes will respond at the same concentration of steroid. Some selectivity can result from the presence of different cofactors, such as coactivators and corepressors that alter the maximal total activity (Amax). Moreover, recent results with the morphogen Decapelaplegic (Dpp) suggest that relative changes in inducing factor concentration can be more important than its absolute concentration (Wartlick et al., 2011).

Other sources of selectivity include gene induction vs. repression, antagonists, and ligand potency. Currently it is difficult to predict, not to mention control, which genes are induced vs. repressed by steroid hormones. It was initially thought that an antisteroid or antagonist would block the action of a given steroid receptor for all genes that it regulated. However, it has become clear that not only do most antisteroids retain some partial agonist activity (PAA), which is exhibited as less than full agonist activity with saturating concentrations of antisteroid, but also the same cofactors that modulate Amax can additionally modify the PAA of antisteroids (Simons; Jr., 2003, Simons; Jr., 2010). Thus an antisteroid that displays 20% of full agonist activity in one circumstance can exhibit 80% of full activity under another condition. A particularly versatile source of selectivity for steroid hormones is ligand potency or EC50, which is the concentration of steroid required for half-maximal activity. While it was believed for many years that the EC50 of steroid-regulated gene expression was directly linked to the affinity of steroid binding to its cognate receptor, numerous studies have established that this view is incorrect (Barton and Shapiro, 1988, May and Westley, 1988, Karim and Thummel, 1992, Reese et al., 1992, Lee et al., 1995, Simons; Jr., 2003, Simons; Jr., 2010). Furthermore, the same cofactors that modify the Amax of agonists and the PAA of antagonists can usually act like a rheostat to alter the EC50 of steroid-regulated gene expression (Simons; Jr., 2003, Simons; Jr., 2010). This modulation is often independent of any effect of cofactor on ligand binding to receptor (Liu et al., 2003). This is particularly true for GRs where coactivators and corepressors appear to bind only to activated complexes of steroid-bound receptors (Cho et al., 2005a, Wang and Simons; Jr., 2005). Furthermore, changing concentrations of coactivator unequally affect the EC50 of different endogenous genes in the same cell with the same GR complex (Luo and Simons; Jr., 2009). This modulation is especially effective because the EC50 of many regulated genes is near the circulating concentration of steroid hormone. Thus, small changes in EC50 can lead to disproportionately larger changes in gene expression. For example, as little as 10% differences in Bicoid concentration have been found to be sufficient to determine the fate of individual cells during Drosophila embryogenesis (Gregor et al., 2007).

From the above examples, it is clear that cofactors not only play a major role in steroid receptor-mediated gene expression but also could be attractive targets for increasing the selectivity of gene transcription. Support for this hypothesis comes from reports that the ability of cofactors to relay the information of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR)-steroid complexes to which they bind can be modified by mutations in the ligand binding domain (LBD) (Tao et al., 2008, Lee and Simons; Jr., 2011). In addition, the magnitude of changes in Amax, EC50, or PAA with these mutants can be very different and is sensitive to the nature of the bound steroid. Similarly, studies in primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) revealed that reducing the endogenous concentration of the coactivator TIF2 differentially affects not only specific genes but also selected properties (Amax, EC50, or PAA) of each gene (Luo and Simons; Jr., 2009). Therefore, the modulatory activity of cofactors is likely to be physiologically, as well as pharmacologically, relevant.

The ability of changing concentrations, or activities, of some cofactors to preferentially modify one or two of the three parameters of GR-regulated gene induction has also been seen with the comodulator Ubc9, which modifies the Amax at low and high GR concentrations but influences the EC50 and PAA only at high levels of GR (Kaul et al., 2002, Cho et al., 2005b, Ong et al., 2010). Interestingly, just the GR LBD was required to mediate the modulatory activity of the full-length TIF2 and Ubc9 proteins (Cho et al., 2005b). These results suggested that defined domains of cofactors might possess different activities that could also be gene specific. If so, it should be possible to selectively modulate cofactor actions by targeting those domains affecting the transcriptional parameter and/or gene of interest. It is well known that distinct regions of coactivators, and the receptors themselves, are critical for Amax in gene induction and repression. However, little is known about the determinants of PAA and nothing is known about those factors influencing EC50 for a given receptor-steroid complex. The government of PAA and EC50 by different molecular interactions and factors than the Amax would raise new mechanistic opportunities for selective control of steroid-regulated gene expression.

The functional combination of GR, TIF2, and STAMP provides an attractive system for investigating which protein domains control Amax, EC50, and PAA. TIF2 is a well-known member of the p160 family of coactivators (York and O'Malley, 2010). STAMP (also called TTLL5) was more recently discovered as a comodulator that binds to TIF2 and augments the ability of TIF2 to increase both GR-regulated gene induction (He and Simons; Jr., 2007) and repression (Sun et al., 2008). The combination of TIF2 and STAMP was found to alter Amax, EC50, and PAA of GR-controlled transcription in a more than additive fashion.

In the present study, we have directly tested the hypothesis that different regions of TIF2 and STAMP affect the individual parameters of GR transactivation. This was accomplished by systematically examining the activities of various combinations of different sized fragments of GR, TIF2, and STAMP. In each case, the activity of the combined truncated proteins was compared to that of the native full-length proteins. This approach with three cooperating factors was selected for two reasons. First, the cooperative nature of the actions of TIF2 and STAMP was expected to amplify the modulation of the three induction parameters, thereby making it easier to detect productive interactions. Second, the number of permutations of potential biologically active protein surfaces is much higher with three than two factors, thereby increasing the possible combinations that could be involved in selective gene transcription. We find that some combinations of protein surfaces can uniquely alter one induction parameter (Amax, EC50, or PAA) independently of the other two. Furthermore, more than one arrangement of surfaces is sufficient to modify most parameters. Finally, this behavior is not unique to one experimental system. Thus there is both specificity and redundancy of receptor and interacting cofactor domains that can contribute to the selectivity of GR-regulated gene expression and provide attractive mechanism-based targets for pharmacological intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

Unless otherwise indicated, all cell growth was at 37 °C and all other operations were performed at 0-4 °C.

2.1. Chemicals

Dexamethasone (Dex) was purchased from Sigma (Louis, MO). Dex-21-mesylate (DM) was synthesized as previously described (Simons; Jr. et al., 1980).

2.2. Plasmids

pSG5 and pBSK+ were purchased from Stratagene and pFLAG-CMV2 was from Sigma. pM and VP16 vector were obtained from Clontech (Palo Alto, CA). pFR-Luc reporter, which contains five repeats of the GAL4 binding element fused upstream of a basic TATA promoter, and the Luciferase reporter were from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). Renilla-TS was a kind gift from N. M. Ibrahim, O. Fröhlich, and S. R. Price (Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA). GREtkLUC (Sarlis et al., 1999), GAL/STAMP623-834, /STAMP623C, pFLAG-CMV2/STAMP, /STAMP392C, and /STAMP623C (He and Simons; Jr., 2007), VP16/GR (Kaul et al., 2000), TIF2.37, TIF2.38, TIF2.4m123 (He et al., 2002), and VP16/GRN523, /GR361C, /GR407C, and /GR486C (Wang and Simons; Jr., 2005) have been previously described. pSG5/GR407C and pSG5/GR524C were both made by PCR by Yunguang Sun, using pSG5/GR as the template. For pSG5/GR407C, the primers were 5’-GGGGGATCCACCATGTCAGTGTTTTCTAATGGGTACTCAAGC-3’ and 5’-CTTGGATCCTCATTTTTGATGAAACAG-3’. For pSG5/GR24C, the primers were 5’-GGGGGATCCACCATGGCAGGAGTCTCACAAGACACTTCGG-3’ and 5’- CTTGGATCCTCATTTTTGATGAAACAG-3’. In both cases, the amplified DNA was then cut with BamHI and inserted into the BamHI site of pSG5. VP16/GR525C was prepared by excising GR525C from GAL/GR525C with Bam H1/Xba 1 and inserting into same site of VP16. pSG5/TIF2,/TIF2.3, /TIF2.4, /TIF2.7, /TIF2.8, and /TIF2m123 were kind gifts from Hinrich Gronemeyer (IGBMC, Strasbourg, France). pHA-GRIP was donated by Michael R. Stallcup (USC, Los Angeles). pSG5/TIF2.3m123 was prepared by first amplifying the TIF2.3m123 fragment by PCR from pSG5/TIF2m123 using 5’-GGAATTCGAGAGAGCTGACGGGCAGAGC-3 and 5’-TTTGGATCCCTACGTGGGCCTGAGGC-3’ as primers. The PCR product was cut with BamHI and inserted into the BamHI site of the pSG5.

2.3. Transient transfection

Triplicate samples of cells were transiently transfected in 24-well plates with luciferase reporter plasmids as described for CV-1 (Tao et al., 2008). Triplicate samples were seeded into 24-well plates in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 20,000 cells per well for MEF and HEK293 cells (DMEM high glucose/10% FBS was used for U2OS cells) and transfected the following day (U2OS and HEK293 cells) or same day 6 h later (MEF cells) in 0.8 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per well according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total transfected DNA was adjusted to 300 ng/well of a 24-well plate with pBluescript II SK (Stratagene). The molar amount of plasmids expressing different protein constructs was kept constant with added empty vector. Renilla-TS (10 ng/well of a 24-well plate) was included as an internal control. After 24 h cells were treated with DMEM/10% FBS containing appropriate hormone dilutions. Sixteen hours later, the cells were lysed and assayed for reporter gene activity using dual luciferase assay reagents according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Luciferase activity was measured by an EG&G Berthold's luminometer (Microlumat LB 96P). In both cases, the data were normalized to Renilla-TS activity and expressed as a percentage of the maximal response with Dex before being plotted (± standard error of the mean, unless otherwise noted).

2.4. Mammalian two-hybrid and three-hybrid assays

The recommended procedure for the Mammalian Matchmaker two-hybrid assay kit (Clontech) was modified slightly by changing from a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase reporter to a Luciferase Reporter, pFRLuc (Stratagene), which is under the control of five repeats of the upstream activating sequence for the binding of GAL4. For three hybrid assays, GR and GR fragments were fused to VP16 and STAMP fragments were fused to GAL. TIF2 and TIF2 fragments were used without any fusion protein.

2.5. Re-immunoprecipitation assays

The method of Vicent et al. (Vicent et al., 2006) was used with the following modifications. The day before transfection, Cos-7 cells were seeded into 150mm dishes at 3,000,000 cells per dish containing 20 ml of DMEM containing 5% FBS. On the next day, cells were transfected with FuGene (Roche) containing 15 mg of DNA/dish. After 24 h, cells were treated with ethanol (EtOH) with or without Dex for 1 h, washed twice with 20 ml of PBS at r.t., cross-linked with 1mM dimethyl 3,3′-dithiobispropionimidate (DTBP) (Pierce, 20665) in PBS for 30 min at 37°C followed by quenching the crosslinking by adding 100 mM Tris (chilled; pH 7.5) at r.t. for 5 min. The cells were washed with PBS at r.t., harvested and lysed by gentle shaking with 1 ml of CytoBuster protein extraction reagent (Novagen) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche; 11836153001) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 1 (Sigma, P2850) and 2 (Sigma, P5726) according to the manufacturer’ instructions for 30 min, and centrifuged for 20 min at 14,000 xg. Supernatant (from two 150 mm plates) was precleared by incubating with 60 ml of 50% slurry of preblocked mouse IgG Sepharose (Sigma; A0919) for 1 h followed by centrifugation at 2000 xg for 1 min. The supernatant was incubated with gentle shaking with 100 ml of anti-FLAG M2 Agarose (Sigma; A2220, preblocked with BSA) overnight. On the next day, the antibody complexes were centrifuged (1 min at 16,000 xg) and washed four times at 4 °C with 1 ml of IP buffer (50mM Tris.HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100). Antibody complex was eluted by incubating with shaking with 2x 150 μl of 25 μg FLAG peptide (Sigma; F3290) in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl and centrifugation (2000 xg for 1 min). The supernatant was reincubated with 2 μg anti-TIF2 antibody (Santa Cruz; sc-8996 [antibody A] or Bethyl A3000-345A [antibody B]) and 40 μl of a 50% slurry of Protein G sepharose (Amersham#17-0618-01) (preblocked with BSA) overnight in 1 ml IP buffer. The beads were then washed four times with IP buffer and protein complexes were extracted with 20 ml of 2x SDS loading buffer (95°C for 10 min), and separated by 4 to 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (NuPAGE, Invitrogen) followed by Western blotting with anti-GR (ABR, PA1-511A or PA1-516), anti-TIF2 (BD Bioscience, 610984), and anti-STAMP (raised against amino acids 1234-1250 (He and Simons; Jr., 2007)).

2.6. Induction of endogenous genes

HEK293 cells seeded into 6-well plates in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/10% FBS at 200,000 cells per well and transfected the following day in 4 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) per well according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total transfected DNA was adjusted to 1.5 μg/well of a 6-well plate with pBSK+. After 24 h cells were treated with DMEM/10% FBS containing appropriate hormone dilutions. For quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), total RNA was extracted by TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The relative levels of target mRNAs were quantitated using SyberGreen (ABI) and the ABI 7900HT real-time PCR system for inositol hexaphosphate kinase 3 (IP6K3) (primers; forward 5’-TTCTCGCTGGTGGAAGACAC-3’, reverse 5’-CAGCAACAAGAACCGATG-3’), glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) (primer sequences were taken from Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2006). β-Actin (primers; forward 5’-GCGAGAAGATGACCCAGATCATG-3’ and reverse 5’-GTCACCGGAGTCCATCACGAT-3’) was measured as control.

2.7. ChIP assays

The basic method of Nelson et al. (Nelson et al., 2006) was modified as follows. HEK293 cells were seeded into 150-mm dishes at 5,000,000 cells per dish in DMEM with 10% FBS and transfected with 15 mg of Plasmid and 45 ml of Lipofectamine 2000 after 24 hr. On the third day, cells were treated with hormones for 1 h, cross-linked with 1 mM DTBP in PBS for 30 min at 37°C followed by crosslinking with formaldehyde (1% final concentration with shaking at r.t. for 10 min). Crosslinking was quenched by adding glycine (125 mM final concentration at r.t. for 5 min with shaking). Cells were harvested by scraping and washed with cold (4°C) PBS with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche; #11836153001). After centrifugation at 885 rpm for 5 min, the cell pellet was resuspended and incubated in 1 ml of cell lysis buffer (50mM HEPES, 140mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% Triton X-100) for 10 min at r.t. The nuclei were collected by centrifugation (800 xg for 10 min at 4 °C) and incubated in 1 ml of protein extraction buffer (200 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 0.5mM EGTA, 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1 at 4 °C) with gentle agitation at 4 °C followed by centrifugation at 800 xg (5 min at 4 °C). Nuclear pellet was resuspended in 300 μl of chromatin extraction buffer (1mM EDTA, 0.5mM EGTA, 10mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1 at 4 °C) and sonicated at 4 °C in a Bioruptor (Biogenode) with a total of six cycles of 30 s on and 30 s off for 5 min each at the High power setting. Samples were centrifuged at 16,627 xg (15 min at 4 °C) after three 5 min cycles and at 16,627 xg (10 min at 4 °C) after the final three 5 min cycles. The supernatant (300 μl) was diluted with 2.7 ml of chromatin extraction buffer and 390 μl of 10% Triton X-100 plus 39 μl 1% sodium deoxycholate, followed by 100 μl of preblocked protein A Sepharose beads (Amersham Pharmacia) with gentle mixing for 1 hr. After centrifugation at 885 xg for 1 min at 4 °C, 100 μl of the supernatant was taken for “Input”. The rest supernatant was divided into 3 tubes (1 ml in each) and incubated with 2 μg of anti-GR (1:1 of PA1-511A + MA1510; Pierce), anti-TIF2 (1:1 of sc8996; Santa Cruz + A300-345A; Bethyl) or anti-STAMP (He and Simons; Jr., 2007) antibody overnight at 4 °C. The next morning, 30 μl of preblocked protein A Sepharose beads was added (1 hr at 4 °C). The pellet was centrifuged (885 xg for 1 min), washed sequentially by 1 ml each of wash buffers I, II, and III (wash buffer I: 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X100, 2 mM EDTA , 20 mM Tris.HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl; wash buffer II: 0.1 % SDS, 1% Triton X100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM, Tris.HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl; wash buffer III: 250 mM LiCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris.HCl, pH 8.0), two times with 1 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer, and then boiled with 100 μl of 10% Chelex 100 followed by centrifugation at 16,627 xg for 5 min at 4 °C. This supernatant was placed in a new tube while 150 μl water was added to the beads, vortexed for 10 sec and centrifuged at 16,627 xg for 1 min at 4 °C. This supernatant was then pooled the above supernatant. The “Input” (see above) was incubated with 1 μl Proteinase K (Fermentas; E0491) and 1 μl RNase A (Fermentas, EN0531) at 65 °C overnight with shaking DNA and then purified using a QIAGEN PCR purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The immunoprecipitated DNA was quantitated by real time PCR using the published primers for the human GILZ (Chen et al., 2006). Primers for the human IP6K3 gene were selected from the known structure of the human IP6K3 gene (Luo et al., submitted): 5’ control at -2471 to -2227 bp (Forward) 5'-GGAAACGACCATGGAGAGAA-3’, (Reverse) -5'-ACATTCCACCACCTGCTTTC-3’, TSS at -107 to 80 bp (Forward) 5'-AGCAGAACACCCAGCTGAC-3’, (Reverse) 5’- CACCATGTACAGGCATCAGG-3’, possible pause site at 60 to 222 bp (Forward) 5'-CCTGATGCCTGTACATGGTG-3’, (Reverse) - 5'-GACCCTCTCTCCCCTCAGTC-3’, GRE at 472 to 679 bp (Forward) 5'-CTGGAGCCCTCTCACTTCAG-3’, (Reverse) 5'-CTGGGCTAGGACATGCTGTT-3’, 3’ control at 2221 to 2378 (Forward) 5'-GGGCAGTTCCAAGAATGTGT-3’, Control (Reverse) - 5'-GTGTGTGGCTGAGGGAGAAT.

2.8. Data analysis

The maximum induced activity (Amax) in cells transiently transfected with GR plasmids was obtained with saturating concentrations of agonist steroid, which was either ≥100-fold higher than the EC50 or 10 μM, whichever was lower. For gene induction, the basal activity is that without steroid and maximal activity is that produced by saturating agonist steroid concentrations. The fold induction is (induced value)/(basal activity). The partial agonist activity (PAA) of the antagonist (DM) was calculated by expressing the activity of a saturating concentration of DM (1 μM) as the percent of maximal activity of a saturating concentration of agonist under the same conditions. For dose-response curves, seven concentrations of Dex are used, with each point being the average of triplicate samples ± the standard deviation. One curve of average points yields one value of EC50 (the concentration of agonist required for 50% of the maximal response) via best-fit curve fitting programs with KaleidaGraph (Synergy Software, Reading, PA) following a first-order Hill plot (R2 almost always ≥ 0.95). For bar graphs giving average values of Amax, EC50, and PAA, the average of n replicates (each in triplicate but considered, statistically, as one observation) was plotted ± the standard error of the mean (n observations) unless otherwise noted. Statistical significance was assessed by the two-tailed Student's t test using InStat 2.03 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). In every case, each average of triplicates was treated as one value of the n experiments. When the difference between the SDs of two populations was significantly different, the Mann-Whitney or Alternate Welch t test was used. A nonparametric test was used if the distribution of values was non-Gaussian.

Data in Tables 1 and 2 are the averages of 1-6 series of experiments, with each series containing 2-6 individual experiments (average = 4) of triplicate determinations (average of each triplicate is recorded as one value). The activity of combinations of protein fragments is expressed as percent of that seen with the three full-length proteins (FFF) on the basis of comparisons with the average values from six independent series of experiments for the FFF complex. The range of S.E.M. values in each series of experiments is almost always 10-25%.

Table 1.

Activities of trimeric GR/TIF2/STAMP complexes relative to FFF (full length protein complex)

| GR/TIF2/STAMP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Properties | |||||

| Complex | GR | TIF2 | STAMP | Amax | EC50 | PAA |

| FFF | F | F | F | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| FFM | F | F | M | 129 | 84 | 76 |

| FFS | F | F | S | 115 | NC | 54 |

| FMF | F | M | F | 107 | 99 | 86 |

| FMM | F | M | M | 177 | 168 | 79 |

| FMS | F | M | S | 96 | NC | 36 |

| FSF | F | S | F | 51 | 47 | 55 |

| FSM | F | S | M | 75 | 67 | 66 |

| FSS | F | S | S | 57 | ND | 38 |

| MFF | M | F | F | 209 | NC | 89 |

| MFM | M | F | M | 309 | ND | 74 |

| MFS | M | F | S | 274 | NC | NC |

| MMF | M | M | F | 224 | 70 | 91 |

| MMM | M | M | M | 309 | 106 | 104 |

| MMS | M | M | S | 160 | -4 | 61 |

| MSF | M | S | F | -6 | Neg | 10 |

| MSM | M | S | M | 6 | 41 | 47 |

| MSS | M | S | S | ND | ND | ND |

| SFF | S | F | F | Neg | Neg | 98 |

| SFM | S | F | M | Neg | ND | NC |

| SFS | S | F | S | Neg | ND | NC |

| SMF | S | M | F | 159 | Neg | 69 |

| SMM | S | M | M | 121 | Neg | 89 |

| SMS | S | M | S | 186 | ND | NC |

| SSF | S | S | F | -70 | -49 | Neg |

| SSM | S | S | M | ND | ND | ND |

| SSS | S | S | S | -37 | ND | -26 |

Key:  = only modulation of EC50 is lost

= only modulation of EC50 is lost

= only modulation of Amax is retained

= only modulation of Amax is retained

= only modulation of PAA is retained

= only modulation of PAA is retained

= only modulation of EC50 is retained

= only modulation of EC50 is retained

= smallest fragment to retain modulatory activity

= smallest fragment to retain modulatory activity

Legend: Neg = change by ternary complex (increase for Amax and PAA, decrease for EC50) is not greater than that of either binary complex (GR + TIF2 or GR + STAMP fragments). Positive values are calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Negative values indicate the percentage by which the activity of the ternary or binary complex is less than that for the GR construct alone of that combination (i.e., lower Amax or PAA or higher EC50), in which case complex formation inhibits the activity of GR. A zero value means that complex formation causes no change in the parameter relative to the relevant GR construct by itself. ND = not done.

Table 2.

Activities of GR/TIF2 and GR/STAMP complexes relative to full length dimeric complex

| GR/TIF2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Properties | |||||

| Complex | GR | TIF2 | - | Amax | EC50 | PAA |

| FF- | F | F | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| FM- | F | M | 86 | 63 | 51 | |

| FS- | F | S | 30 | 35 | 29 | |

| MF- | M | F | 289 | 156 | 127 | |

| MM- | M | M | 205 | 117 | 144 | |

| MS- | M | S | 6 | 123 | 24 | |

| SF- | S | F | 196 | 96 | 158 | |

| SM- | S | M | 189 | 165 | 117 | |

| SS- | S | S | -3 | 15 | 39 | |

| GR/STAMP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Properties | |||||

| Complex | GR | - | STAMP | Amax | EC50 | PAA |

| F-F | F | F | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| F-M | F | M | 169 | 40 | 98 | |

| F-S | F | S | 97 | 35 | 15 | |

| M-F | M | F | 4 | -28 | 59 | |

| M-M | M | M | 23 | 42 | 75 | |

| M-S | M | S | -2 | -29 | 0 | |

| S-F | S | F | -57 | -52 | 19 | |

| S-M | S | M | -49 | ND | 20 | |

| S-S | S | S | -32 | ND | 0 | |

3. Results

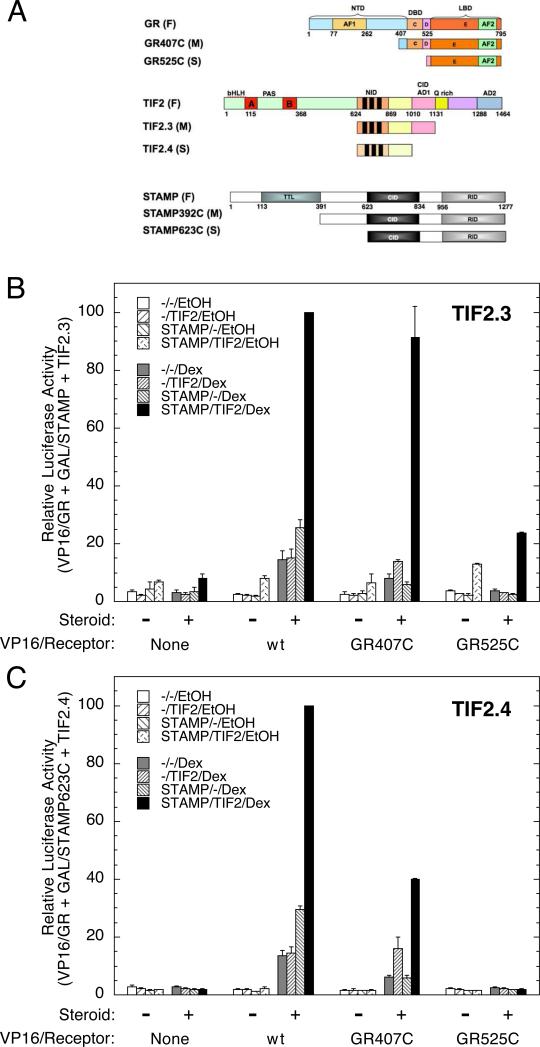

3.1. Modulatory activity of TIF2 and STAMP with GR

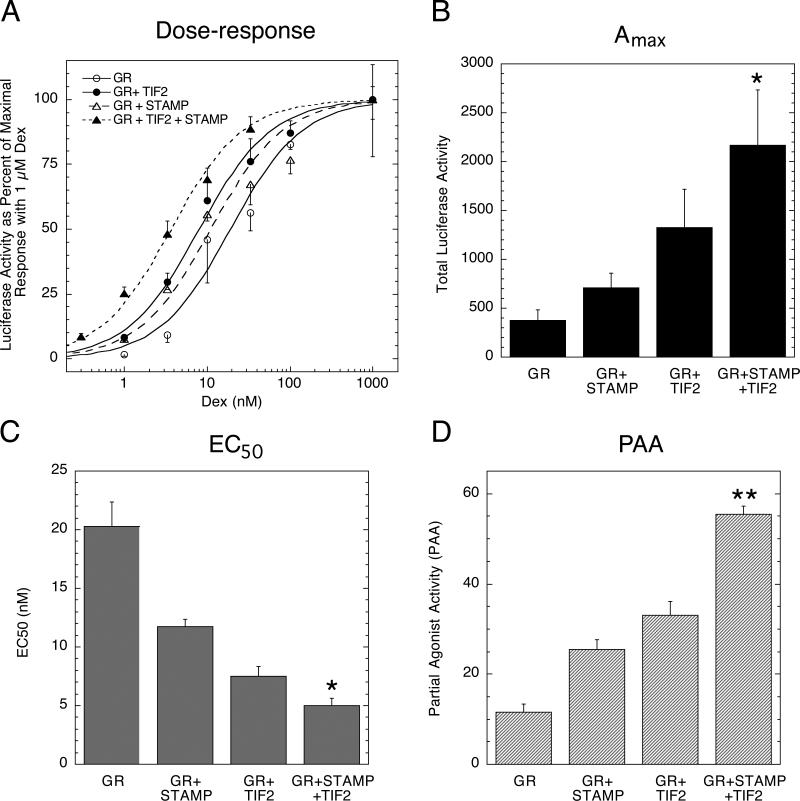

We first confirmed the suitability of using TIF2 plus STAMP to modulate GR induction properties (He and Simons; Jr., 2007). Dexamethasone (Dex) is used as the pure agonist for full induction. The antiglucocorticoid employed is Dex-21-mesylate (DM), which displays a variable amount of partial agonist activity under a variety of conditions (Szapary et al., 1999). A single representative experiment is presented in Fig. 1A, with Figs. 1B-D summarizing the results of four independent experiments. These results establish that the combination of transiently transfected TIF2 and STAMP increases the Amax of Dex and PAA of DM, and decreases the EC50 of Dex, for GR-regulated induction of a synthetic reporter gene (GREtkLUC) in CV-1 cells in an additive or more than additive manner.

Fig. 1.

Modulatory activity of TIF2 and STAMP with GR-regulated gene induction of synthetic reporter gene. CV-1 cells were transiently transfected as described in Materials and Methods with GR (6 ng) with or without TIF2 (20 ng) and/or Flag/STAMP (160 ng) plus GREtkLUC reporter (100 ng) and Renilla control (10 ng). After incubation with the indicated concentrations of steroid, vehicle (EtOH), or 1 μM DM in triplicate, the amount of induced luciferase was determined and the data plotted as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Dose-response curves for luciferase induction by GR plus indicated cofactors. Graph is one representative experiment with the error bars being the S.D. of each triplicate steroid treatment. (B) Maximal activity (Amax), (C) steroid potency (EC50) and (D) partial agonist activity (PAA). The average Amax with 1 μM Dex, the average EC50 (nM) with Dex, and the average partial agonist activity of 1 μM DM from four experiments such as in A were determined for the indicated grouping of factors. Error bars equal S.E.M. (n=4). P values for GR+STAMP+TIF2 vs. GR+TIF2 are * = <0.05, ** = < 0.005.

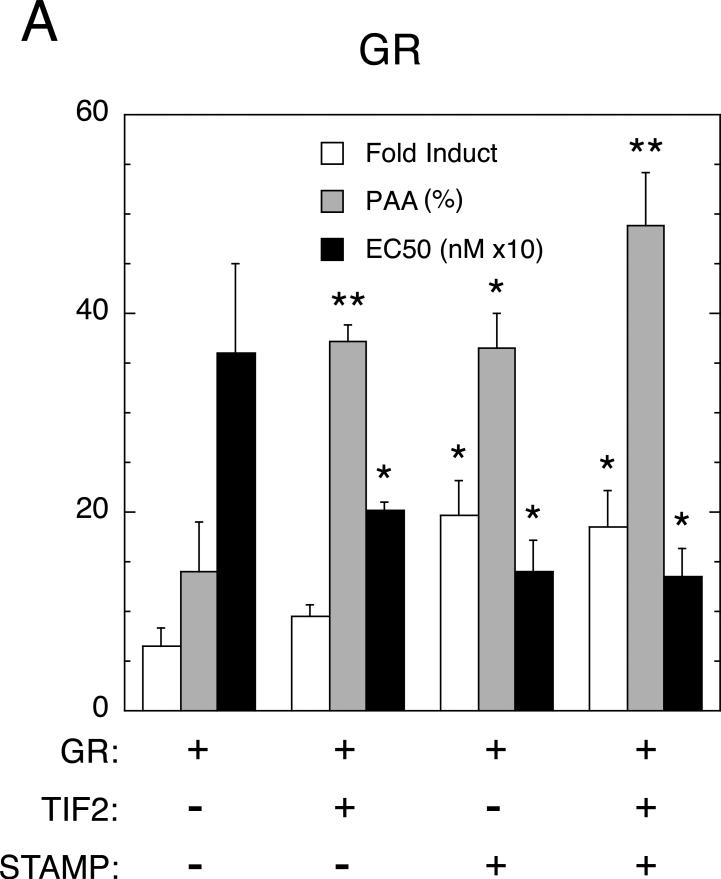

To determine if similar effects occur with an endogenous gene, we turned to 293 human embryonic kidney cells and the IP6K3 (also called I6PK) gene. Very little is known about the IP6K3 gene other than that it is inducible by glucocorticoids (Rogatsky et al., 2003, Lee and Simons; Jr., 2011). After transient transfection of GR without or with TIF2 and/or STAMP, the levels of IP6K3 mRNA were determined and plotted as in Fig. 1. The only difference is that the fold induction was plotted because the qRT-PCR determinations with SYBR Green cannot give absolute measurements of cDNA concentrations. When the basal levels are the same, as they are here, there is very little difference between using fold induction and Amax of Dex. As shown in Fig. 2A, the combination of exogenous TIF2 and STAMP causes changes in the PAA of DM, and the EC50 of Dex, that are significantly different from that for GR alone and somewhat to marginally greater than those with either factor alone. As expected, ChIP assays (Fig. 2B) reveal that GR, TIF2, and STAMP are each preferentially recruited in a steroid-dependent manner to the GRE, which is in the first intron of the IP6K3 gene (Luo et al., submitted). This behavior is gene-selective, though, and was not seen in the same 293 cells for another gene, GILZ (data not shown), which is consistent with the weak induction of GILZ mRNA (2.8 ± 0.6 fold, S.E.M., n=4) and the inability of added TIF2 and/or STAMP to either increase the fold induction by Dex and the PAA of DM or to decrease the EC50 with Dex (data not shown). This contrasts with the more robust average of a 10-fold induction of GILZ by GR, which is accompanied by the recruitment of GR to the promoter region, that has been reported for other cell lines (Rogatsky et al., 2003, Chen et al., 2006, Avenant et al., 2010).

Fig. 2.

GR-induction properties of endogenous IP6K3 gene with added TIF2 and STAMP in 293 cells. (A) Modulation of parameters of IP6K3 gene induction by transiently transfected full-length GR with TIF2 and STAMP. Experiments were conducted as described in Materials and Methods, with IP6K3 induction being determined by qRT-PCR. Data were then processed and analyzed as in Fig. 1 except that fold induction by 1 μM Dex was quantitated as opposed to Amax. Of relevance is the fact that the basal levels of IP6K3 mRNA expression were essentially the same for each treatment. Note that the y-axis is dimensionless in panels A and C because the bars being plotted have their own associated units (fold induction, percent of maximal activity for PAA, and nM × 10 for EC50). (B) Binding of GR, TIF2, and STAMP to IP6K3 gene. ChIP assays were performed as outlined in Materials and Methods with U2OS cells that were transiently transfected with full-length GR, TIF2, and STAMP followed by treatment with vehicle (EtOH), 1 μM Dex, or 1 μM DM. Primers for PCR amplification were selected to probe protein recruitment to control regions about 2.3 kb upstream and downstream of the transcription start site (TSS), the TSS, a possible pause site at +60-220, and the intronic GRE. Anti-Flag antibody was used to assess non-specific binding of GR, TIF2, and STAMP to each region. Error bars represent S.E.M. (n = 4-6). (C) Induction parameters of IP6K3 gene with truncated GR407C with TIF2 and STAMP. Experiment is the same as in panel A except truncated GR407C is used in place of full-length GR. For both panels A and C, error bars equal S.E.M. (n=4) with P values being for comparisons with data for receptor (GR or GR407C) alone are * = <0.05, ** = < 0.005, *** = <0.0005.

We have previously reported that the amino terminal half of GR is not required to mediate the modulatory activity of the individual addition of several full-length cofactors (Cho et al., 2005a, Cho et al., 2005b, Tao et al., 2008, Lee and Simons; Jr., 2011). We therefore asked, again in 293 cells, whether the truncated rat GR (GR407C) lacking the amino terminal 406 residues was similarly able to respond to added TIF2 ± STAMP in the induction of IP6K3. Using GR407C in place of the full-length GR, an even more robust response with TIF2 and STAMP was obtained compared to either cofactor alone (Fig. 2C). Under these conditions, the changes in fold induction, EC50, and PAA with TIF2 plus STAMP are the same as, or larger than, the sum of the effects of both factors in isolation. Under these same conditions in the same cells, TIF2 and STAMP again have little if any ability to modify the fold induction, EC50, and PAA of GR-mediated induction of GILZ (data not shown). The fact that added cofactors alter the EC50 of IP6K3, but not GILZ, with the same GR complex argues persuasively that these effects are independent of effects of cofactor on ligand binding to GR. Instead, the modulatory activities of TIF2 and STAMP combinations are sensitive to the nature of the endogenous gene in a manner that is not unique to CV-1 cells or synthetic reporters.

3.2. Ternary complex formation of GR, TIF2, and STAMP in three-hybrid assays

A simple explanation for the additive, and sometimes cooperative, modulatory activity of TIF2 and STAMP with GR is that all three proteins form a complex to modify gene transcription. As a first test of this hypothesis, we used a three-hybrid assay to examine the ability of one protein to augment the activity of the other two in a classical mammalian two-hybrid assay. At the same time, this assay allows us to begin to examine what domains of which proteins are required for the formation of the functional ternary complex. For this and other assays below, we selected two progressively more truncated species of each factor (Fig. 3A). In addition to the full-length protein (F), medium-length (M) and short length (S) constructs were prepared. In every case, the smallest fragment of each protein was selected on the basis of previous reports that some activity for modulating the induction parameters with the full-length GR is retained (He et al., 2002, Cho et al., 2005b, He and Simons; Jr., 2007). The medium-length fragment was constructed to have one more functional domain than the smallest fragment (e.g., the DBD of GR in GR407C and the AD1 domain in TIF2.3). The region corresponding to amino acids 392-622 of STAMP has been reported to augment a different activity of STAMP, i.e., its ability to polyglutamylate proteins (van Dijk et al., 2007).

Fig. 3.

Interaction of GR, TIF2, and STAMP in mammalian three-hybrid assays. (A) Cartoon of different size constructs of each factor. Maps of full (F), medium (M), and short (S) length fragments of GR, TIF2, and STAMP are shown along with the known domains of GR and TIF2. For STAMP, the domains are tyrosine tubulin ligase (TTL), coactivator interaction domain (CID), receptor interaction domain (RID) (He and Simons; Jr., 2007). The full names of the medium and short species of GR and STAMP include a number and the letter “C”, which indicate the first amino acid and the C-terminal amino acid of each species. The TIF2 names are those of Voegel et al. (Voegel et al., 1998). Three-hybrid assays with (B) TIF2.3 or (C) TIF2.4 cotransfected with the indicated VP16/GR fusions, GAL/STAMP623C, and the GAL regulated reporter FRLUC without or with 1 μM Dex. Luciferase activity (in triplicate) was determined as described in Materials and Methods, after which the data were normalized to the highest activity. Error bars in graphs are S.E.M. (n= 2-3 [TIF2.3] or 2 [TIF2.4] independent experiments).

As a first step in detecting interactions between the various species of Fig. 3A, we selected all three GR species in combination with the two smallest TIF2 constructs and the shortest STAMP species. Various combinations were compared for their ability to synergistically increase the activation of a GAL4 responsive reporter that occurred upon adding the synthetic glucocorticoid Dex to cells that were cotransfected with VP16 activation domain chimeras of various GR species, either of the two TIF2 fragments, and the fusion construct of the GAL4 DNA binding domain with the smallest STAMP molecule (see Fig. 3A). With exogenous TIF2.3, a more than additive interaction in the presence of Dex is maintained with the smallest fragment of GR (GR525C) and STAMP (STAMP623C) (Fig. 3B). However, the ability of VP16/GR525C and GAL/STAMP623C to cooperatively increase Luciferase induction with TIF2 is lost when adding TIF2.4, which is the smallest TIF2 fragment examined (Fig. 3C). This is not an artifact of inadequate levels of functional TIF2.4, as shown both by the robust activity of TIF2.4 with VP16/wt GR in Fig. 3C and by Western blots of expressed TIF2.4 protein (data not shown and Cho et al., 2005a). Thus, these data suggest that the modulatory activity seen in Figs. 1 and 2 disappears when large segments of each protein are removed.

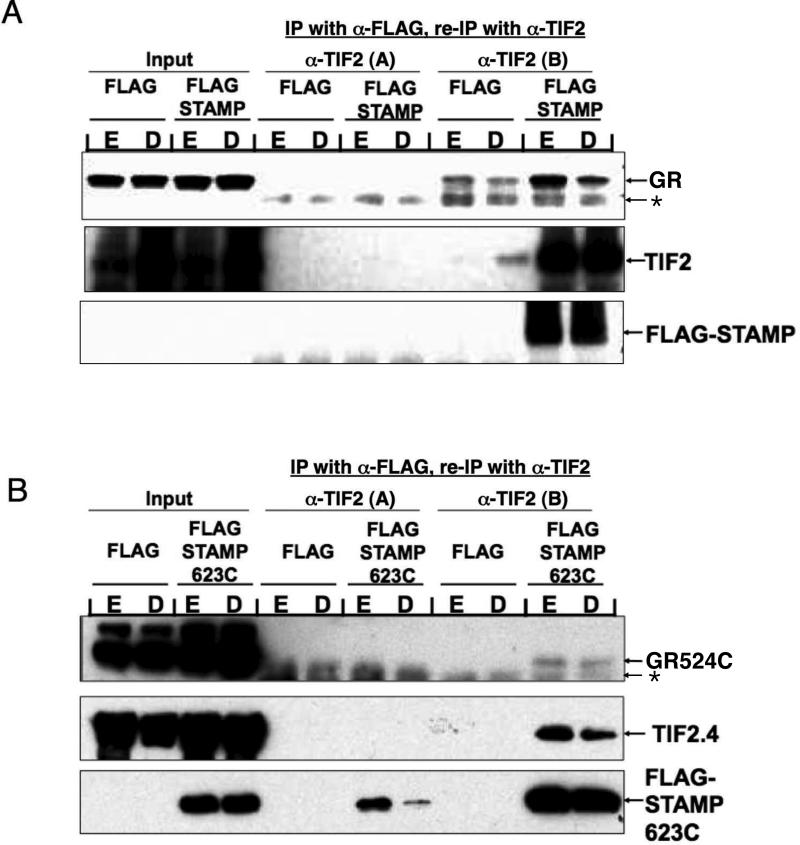

3.3. Full-length and short forms of GR, TIF2, and STAMP yield ternary complexes

The lack of gene induction in Fig. 3C by the smallest fragments of GR, TIF2, and STAMP could be due to the absence of a ternary complex. In an effort to provide direct evidence for the presence of this ternary complex, we used the co-IP/re-co-IP method of Vicent et al. (Vicent et al., 2006). Here, light cross-linking with dimethyl 3,3′-dithiobispropionimidate (DTBP) is used to preserve the integrity of multimeric complexes during the potentially disruptive conditions of washing and resuspension of the first immunoprecipitate. With the full-length proteins, a ternary complex is specifically detected in Western blots of the IP/re-IP sample (Fig. 4A). The low amount of GR that is co-IP'd under control conditions (anti-Flag, followed by anti-TIF2 [B]) appears to be unrelated to the ternary complex as little or no TIF2 or Flag-STAMP is also present. The formation of a complex in the absence of Dex appears to be due to the fact that, under cell-free conditions, steroid-free GRs are readily activated with regard to binding both DNA (Cho et al., 2005a) and cofactors such as the corepressor NCoR (Wang and Simons; Jr., 2005).

Fig. 4.

Existence of ternary complexes of GR, TIF2, and STAMP. IP/re-IP assays of lightly cross-linked complexes of (A) GR/TIF2/Flag-STAMP and (B) GR524C/TIF2.4/Flag-STAMP623C from cells treated with EtOH (E) or 1 μM Dex (D) were conducted and visualized as described in Materials and Methods. Flag plasmid was used in place of Flag-STAMP as a negative control for the first IP. Anti-TIF2 antibody A is a non-precipitating anti-TIF2 antibody that was used as a negative control for the re-IP. Due to the low levels of expression of Flag-STAMP, it is not detected by Western blotting until after the IP. * = non-specific impurity.

Under the conditions of Fig. 4A, the smallest fragments of each protein (using the available GR524C as opposed to GR525C) also form a ternary complex (Fig. 4B). The apparent disagreement of these results with the three-hybrid data of Fig. 3 could be due to two situations. First, the ternary complex may form in the three-hybrid assay but is biologically inactive (see below for confirmation). Alternatively, it is known that three-hybrid assays are unable to detect weakly bound complexes (de Felipe et al., 2004). In either case, it appears that additional domains are required either for transcriptional activity or to afford a more stable ternary complex with increased transcriptional activity. Thus, by adding back individual domains, it should be possible to determine whether the modulation of Amax, EC50, and PAA in GR-regulated gene induction by TIF2 and STAMP are all recovered at the same time or whether separate domains are utilized for the modulation of individual parameters.

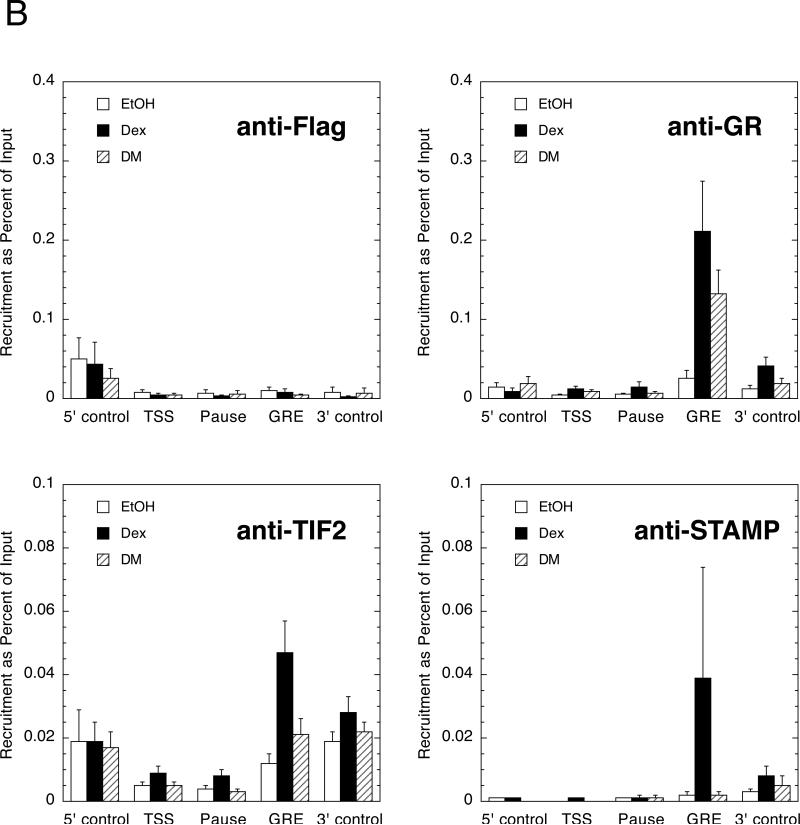

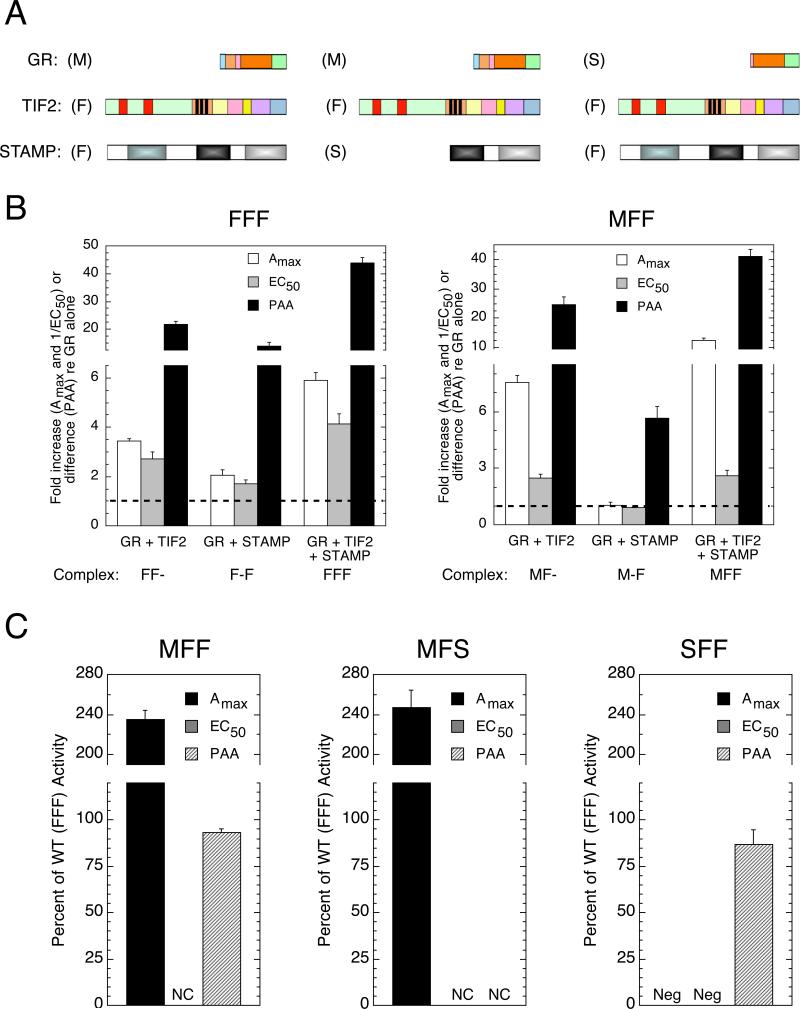

3.4. Determination of regions in ternary complexes required for modulation of Amax, EC50, and PAA

Using the three species (F, M, S) of each protein in Fig. 5A, there are 33, or 27, different possible combinations of constructing a ternary complex containing one molecule from each parent factor. Combinations with full-length (F) and medium-length (M) GR were examined with the same reporter (GREtkLUC) in the same cells (CV-1) as above. For the GR525C (the short [S] form of GR), we used the chimera of GAL4 DBD fused upstream of GR525C and determined the parameters for its induction of the GAL-regulated luciferase reporter (FRLuc), again in CV-1 cells. The use of GAL/GR525C in comparisons with full-length GR is reasonable as we have previously documented that GAL/GR525C induction of FRLuc faithfully mimics the properties of the wild type GR with the GREtkLUC reporter in the presence of several antiglucocorticoid steroids and a variety of full-length cofactors added one at a time (Cho et al., 2005a, Cho et al., 2005b, Tao et al., 2008, Lee and Simons; Jr., 2011).

Fig. 5.

Regions of GR, TIF2, and STAMP required for modulation of Amax, EC50, and PAA. (A) Cartoon of different size constructs of each factor, as described in Fig. 3A. For clarity, the GAL DBD that is fused to GR (S) to give GAL/GR525C is not shown. (B) Effect of factor combinations on induction parameters. The experiments were conducted as in Fig. 1 for different combinations of full-length GR, TIF2, and STAMP (F, F, F) and of medium-length GR with full-length TIF2 and STAMP (M, F, F). The data for each combination of factors are presented as fold increase above that for the GR species of that series by itself for Amax and for 1/EC50 (so that increased potency is displayed as an increase relative to the same GR alone, i.e., GR(M) in MFF series) and as the absolute change in percent agonist activity for PAA (error bars = S.E.M., n = 4 individual experiments). The composition of the binary and ternary complexes in each panel is given at the bottom of each panel. The dashed line represents the level of no change relative to full-length GR. (C) Effect of factor combinations on induction parameters relative to those with full-length proteins. The “percent of wt (FFF) activity” for a given combination (e.g., MFF of panel B) was calculated by dividing the fold increase (or difference in the case of PAA) of the test complex (e.g., MFF) by that of the paired wt standard (e.g., FFF in panel B) as described in the text and Materials and Methods. The data of two other representative series of experiments are also shown for MFS and SFF. NC = no change relative to the paired GR plus TIF2 (or plus STAMP). Neg = negative value compared to the paired GR plus TIF2 (or plus STAMP). It should be noted that the responses of GR + TIF2 are almost always greater than GR + STAMP. Error bars = S.E.M. (n = 4-5).

Twenty-five different combinations were examined in at least one set of a minimum of three experiments and compared to the results with either the full-length proteins (abbreviated as FFF) or some other combination (e.g., medium-length constructs of each protein, or MMM) that had been previously calibrated against FFF. In each case, the letters F, M, or S (indicating full, medium, or short length of the proteins; see Fig. 5A) are listed in the order of GR, TIF2, and then STAMP. Each set of experiments consists of at least three independent experiments using triplicates for each steroid concentration as illustrated in Fig. 5B for FFF and MFF. The average total modulatory activity displayed with each triplicate determination of the indicated combination of factors is considered as one value and is then compared to that of the reference complex (i.e., GR(F) for FFF and GR(M) for MFF in Fig. 5B) in the same individual experiment. The dashed line in each panel indicates no change relative to GR alone. The amount of modulatory activity for the ternary MFF complex is then displayed as a percent of activity for the wild type full-length proteins (FFF) in the left hand panel of Fig. 5C. These values are calculated as follows. For Amax, the fold change in Amax is compared (= [(fold increase in Amax for MFF)-1]/[(fold increase in Amax for FFF)-1]). For EC50, again the relative fold change in EC50 is determined (= [(fold increase in 1/EC50 for MFF)-1]/[(fold increase in 1/EC50 for FFF)-1]). In both cases, this relative comparison is calculated to neutralize the inherent differences in absolute Amax activities and EC50s for the three different GR complexes (F, M, and S). Two forms (M or GR407C and S or GAL/GR525C) lack the amino terminal transactivation domain AF1 while one form (S) induces a different reporter construct (i.e., FRLuc instead of GREtkLUC). This mode of comparison is appropriate because we are determining the modulatory activity of the different constructs, i.e., their ability to cause the same fold changes in Amax and EC50 as seen with the full-length proteins. Whether or not the absolute values of Amax and EC50 are the same for truncated vs. full-length proteins is not an objective of this study.

As shown in Fig. 5B, the absolute change in PAA is monitored instead of fold increase. This was done because the range of PAA values is not open ended, like Amax and EC50, but rather is bounded between 0 and 100% of full agonist activity under the same conditions. Thus a change in PAA of 60 percentage points from 30% to 90% of Amax is only a 3-fold increase but is considered greater than the 10-fold increase of 1% to 10%, which is an increase of 9 percentage points. Therefore, for PAA, a comparison of absolute changes is considered to be more accurate than fold changes as a measure of factor modulatory activity. To obtain the relative modulatory activity of MFF for PAA, compared to the wild type proteins (FFF) that is shown in Fig. 5C, the relative change in absolute PAA is calculated (= [absolute increase in PAA for MFF]/[absolute increase in PAA for FFF]).

The modulatory activity of the ternary complex was termed negative (Neg) if it is less than that of the most active binary complex (i.e., the same GR + TIF2 or GR + STAMP fragments). This behavior indicates that the added third factor is acting as a dominant negative inhibitor. If there was no difference between the ternary complex and one of the binary complexes, the response is labeled as no change (NC). In this case, the third factor is inactive. A negative number (or zero) means that the value of that parameter for a given combination of constructs is less than (or equal to) that seen for just the GR species by itself, again indicating dominant negative activity. The magnitude of the negative number (or zero) reflects the percent change in each parameter (reduction for Amax and PAA, increase for EC50) relative to the value obtained with just the GR species.

Fig. 5C shows three particularly interesting combinations of constructs: MFF, MFS, and SFF. The values for MFS and SFF were calculated as described above for MFF. In each grouping, all three parameters are not equally affected. With MFF, the ability to modulate the EC50 is lost while nearly wild type protein activity (or more) is retained for altering the Amax and PAA. The greater than wild type activity of MFF relative to FFF for changing the Amax is presumably due to the fact that the shorter fragments of each protein (in this case, GR407C) are expressed in greater concentration than the full-length protein (data not shown). Such higher levels of expression of the fragments of each full-length protein increase the capacity to detect an altered transactivation parameter in the ternary complex. Importantly, this heightened sensitivity makes the inability of those complexes of truncated proteins to modulate selected parameters even more significant. It should be noted that the quantitation of all three parameters for a given ternary complex under the same conditions often provides a valuable internal control. For example in Fig. 5C, the failure of the higher amounts of expressed GR and STAMP in the MFS combination to influence either the EC50 or the PAA, while causing an even greater increase in Amax than seen with the full-length proteins, strongly argues not only that all fragments are being expressed but also that the interactions required to influence EC50 and PAA, but not Amax, are missing. Thus, under identical conditions, some parameters are affected while others are not, even under conditions where the higher levels of overexpressed truncated proteins (relative to full-length protein) would amplify any residual modulatory activity of Amax, EC50, or PAA.

Removing the amino terminal half of STAMP changes the MFF combination to MFS. This deletion is accompanied by the loss of the capacity the MFF complex to modify the PAA of DM. Alternatively, further truncation of the GR (from the M of GR407C to the S of GAL/GR525C) results in the SFF complex being able to modulate only the PAA. Both STAMP (S) and GR (S) are active in combination with other constructs (see below). This further argues that the inability of STAMP (S), or GR (S), to modify some parameters in Fig. 5C is not due to insufficient expression of each construct. These results clearly show that changes in Amax, EC50, and PAA are not regulated in concert by the same regions of these three proteins. Instead, selected domains of each protein can make different contributions to altering individual induction parameters, sometimes without affecting one or both of the other parameters under identical conditions.

The data for 25 of the 27 possible combinations of GR/TIF2/STAMP were determined as described above for Figs. 5B&C and listed in Table 1. There are groupings in addition to those of Fig. 5C that are no longer able to modify just the EC50 (highlighted in yellow in Table 1) or where only the Amax is altered (highlighted in red). In some situations, all three parameters are equally affected (FMF, FSF, and FSM). In other cases, the different truncated proteins modulate all three parameters (Amax, EC50, and PAA) but the magnitude of change is not equal for each parameter (e.g., FMM, MMF, and MMM). Furthermore, using 50% of the activity of the wild type proteins (FFF) as an arbitrary breakpoint, there is more than one combination of factor domains that retains modulatory activity for each parameter. As indicated by the bold boxing, the combinations of FSS and SMS are the “smallest” combinations that are able to modify Amax. This suggests that SSS might also regulate Amax but this is not the case. Similarly, MMS and SMM appear to be arrangements of the “smallest” factors capable of altering the PAA. This suggests that SMS would also be able to change the PAA but this is not true. Finally FSM and MMM are sufficient to change the EC50 but MSF is not. Thus it appears that there is more than one permutation of protein domains that can combine to modulate each parameter for gene induction. Also of interest is that more domains of all three proteins are required to change the EC50 than the Amax or PAA. Not only are there more combinations that are inactive with regard to modifying the EC50 than the other two parameters but also the ability to alter the Amax and PAA by greater than 50% is seen with more groupings of smaller protein constructs (i.e., SMS, SMM, and MMS) than for the EC50, where no combination smaller than MMM is active. Finally, Table 1 shows that every construct (F, M, S) of each factor (GR, TIF2, STAMP) is able, in at least one ternary complex, to increase the Amax and PAA above that seen with just the other two constructs. This establishes not only that biologically significant quantities of each construct are being expressed in these assays but also that the inactivity of a given construct in a specific combination is not due to some generalized interference.

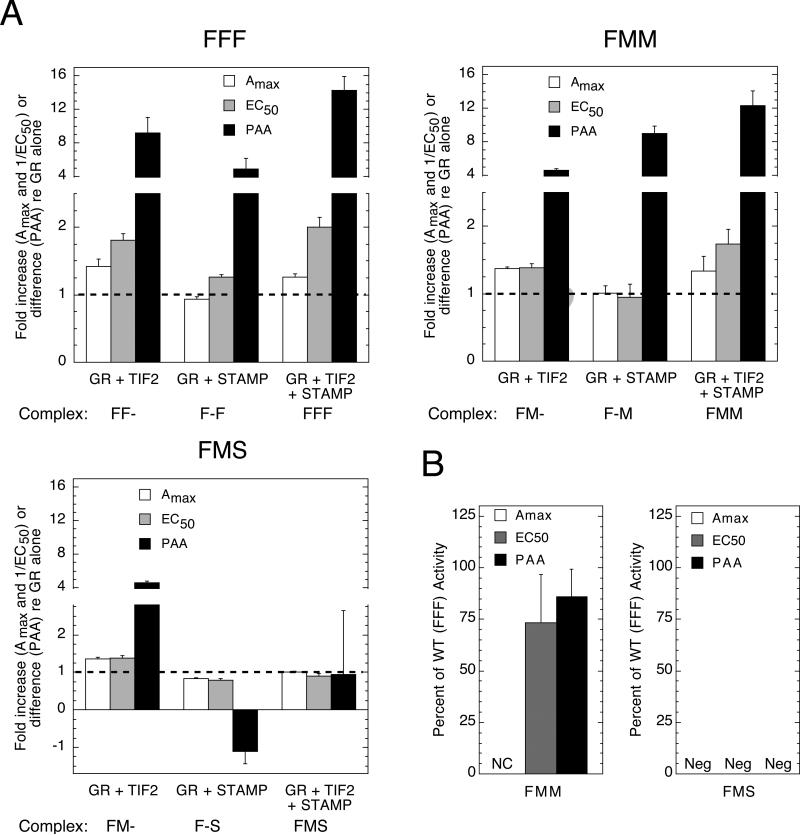

3.5. Determination of regions in binary complexes required for modulation of Amax, EC50, and PAA

While the data in Table 1 are all for ternary complexes, the experiments necessary to obtain these values include an examination of both binary complexes (GR + TIF2 and GR + STAMP), as shown in Fig. 5B. Therefore, the above experiments simultaneously provide information on the modulatory activity of the different domains of GR with those of TIF2 and of STAMP. These values are presented in Table 2. Interestingly, in contrast to the trimeric complexes, the modulation of EC50 by the binary GR-TIF2 complexes appears to be the least affected by deletions. The combination of GR (M) and TIF2 (S), highlighted in green, retains significant activity only for modifying the EC50 of gene induction. With the shortest forms of both proteins (SS), the ability of this complex to modify any parameter is below our arbitrary cutoff of 50% while the slightly larger complex of SM displays full activity. A greater percentage of full-length STAMP than TIF2 is needed to modify the induction parameters. No form of STAMP is significantly active with the GAL/GR525C (the short form of GR) while most combinations of STAMP with GR (M) have less than 50% activity. As seen above with the ternary complex (same color coding used), the ability to modify the EC50 is the first activity to be lost when any deletion of STAMP is assayed with full-length GR (F).

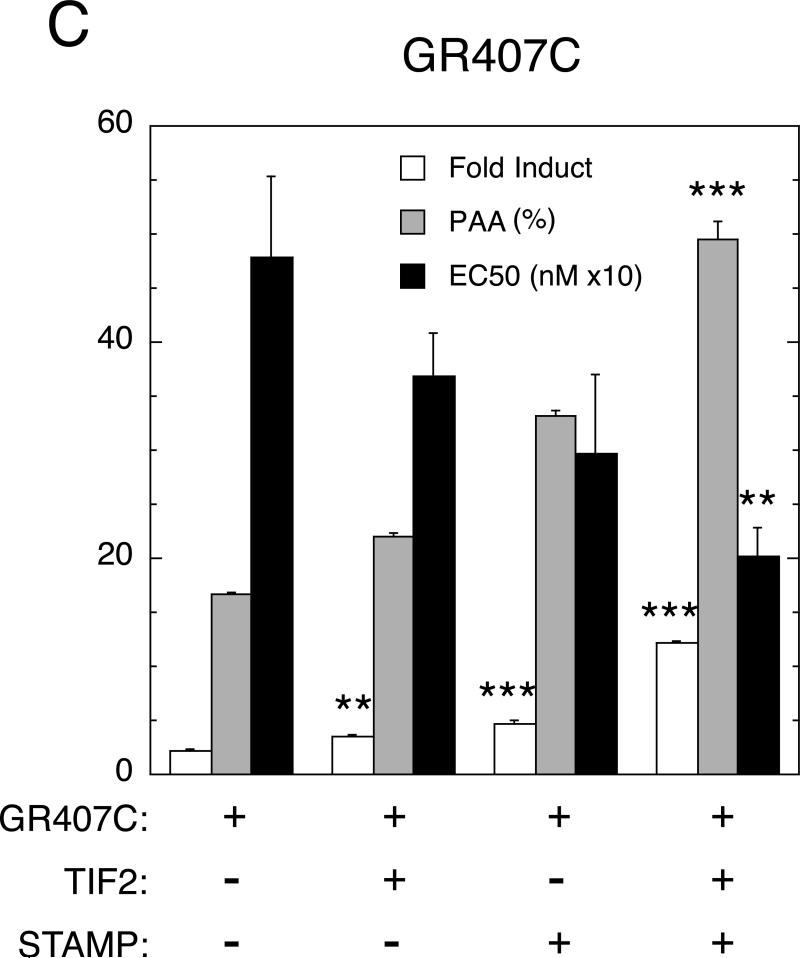

3.6. Modulatory activity of factor fragments in other cells

The induction properties of GREtkLUC reporter by three combinations of GR/TIF2/STAMP were next examined in transiently transfected 293 cells: FFF, FMM, and FMS. The actual fold, or absolute, change for each combination of factors (both binary and ternary complexes) is presented in Fig. 6A in the same format as in Fig. 5B above. This allows the modulatory activity of both the two binary complexes and the ternary complex to be presented in the same graph. The dashed line represents the relative value of each parameter with just the GR construct. The two full-length binary complexes (FF- and F-F) alter the EC50 and PAA but only GR + TIF2 (FF-) affects the Amax. The ternary complex of FFF modifies only the PAA of DM more than that of either binary complex alone. Similar results are seen for the FMM complex. With further truncation of STAMP to give the FMS complex, both the GR-STAMP and the ternary complex have lost all modulatory activity. This is not due to major differences in abundance of the M and S forms of STAMP as Western blots show that STAMP (S) is actually more abundant (data not shown). Thus again, different domains of the various factors participate in the modulation of different induction parameters.

Fig 6.

Activity of modulatory regions of GR, TIF2, and STAMP is cell-dependent. The indicated constructs of GR, TIF2, and STAMP were transiently transfected into 293 cells along with the GREtkLUC reporter. The experiments were conducted and plotted as in Fig. 5. (A) Effect of factor combinations on induction parameters in 293 cells. The data for each combination of factors are presented as in Fig. 5B as fold increase above that for corresponding GR alone for Amax and for 1/EC50 (so that increased potency is displayed as an increase relative to same GR alone, e.g., GR(F) for FMS series) and as the absolute change in percent agonist activity for PAA. The composition of the binary and ternary complexes in each panel is given at the bottom of each panel. The dashed line represents the level of no change relative to full-length GR (error bars = S.E.M., n = 4 individual experiments). (B) Effect of factor combinations on induction parameters relative to those with full-length proteins in 293 cells. The “percent of wt (FFF) activity” for a given combination was calculated from the data in panel A as described for Fig. 5C. NC = no change relative to the paired GR plus TIF2 (or plus STAMP). Neg = negative value compared to the paired GR plus TIF2 (or plus STAMP). Error bars = S.E.M. (n = 4 individual experiments).

Discussion

All three parameters of GR-regulated gene expression (Amax, EC50, and PAA) are usually assumed to be determined by the same factors and mechanism. This study reveals that each parameter is independently controlled under some conditions. The system used to derive this conclusion involves the cofactors TIF2 and STAMP, which are known to modulate each parameter in cases of GR-mediated induction and repression of exogenous reporter genes when employing the full-length proteins (He and Simons; Jr., 2007, Sun et al., 2008). We confirm this behavior and show that the alteration of these three parameters (Amax, EC50, and PAA) also occurs with an endogenous gene (Fig. 2) in a gene-selective manner (i.e., IP6K3 vs. GILZ). Thus, changes in these three parameters occur under physiologically relevant conditions.

Dex-induced recruitment of all three factors (GR, TIF2, and STAMP) to the intronic GRE of the IP6K3 gene (Luo et al., submitted) is observed. Steroid-regulated gene transcription has recently been found to involve the pausing of RNA polymerase II at a region about 100 bp downstream of the TSS (Core and Lis, 2008, Price, 2008, Kininis et al., 2009). We were unable to detect any association of GR, TIF2, or STAMP in the predicted region of the IP6K3 gene for a paused polymerase (Fig. 2). Additional studies are required to determine whether changes in the duration of polymerase pausing, or mode of release of paused polymerase, affects Amax, EC50, or PAA.

Studies with transiently transfected factors and reporter gene were then employed in order to gain a more detailed understanding of the modulation of Amax, EC50, and PAA. Direct observation of a ternary complex of GR, TIF2, and STAMP is detected, even when relatively small portions of each protein are used (Fig. 4). However, the combination of smallest fragments fails to display increased activity in a three-hybrid assay (Fig. 3C). This observation was pursued in a bioassay with ternary complexes of a series of progressively smaller protein segments. By deleting increasingly large segments of GR, TIF2, and STAMP, it was found that different domains can independently affect each of the three parameters of GR-mediated induction (Fig. 5 and Table 1). The same phenomenon is seen for the actions of TIF2 or STAMP alone with GR (Table 2), again sometimes to the exclusion of one or two of the other parameters. This differential modulatory activity is not unique to CV-1 cells and is also seen with 293 cells (Fig. 6).

All conditions are not capable of revealing unequal influences on Amax, EC50, and PAA. However, the few clear-cut examples of separable control of these three parameters are sufficient to establish mechanistic non-equivalence. This methodology differs from conventional studies in two respects. First, we ask if a combination of three factors that changes one parameter always causes similar changes in the other two parameters. Second, the most important changes are those where, as in Fig. 1, the combined effect of all three factors is greater than that of any binary pair. This requirement automatically assures that all three factors are being expressed. For example, if one factor is not expressed (which is functionally identical to the expression of an inactive construct), there will be no change (NC in Table 1) in any of the three parameters from that when just the other two factors are expressed (it should be noted that this result is never seen in Table 1). If, however, one or two of the parameters are unequally affected (as is the case in Fig. 5C), then the unavoidable conclusion is that all three constructs are expressed at significant levels and that all three parameters (Amax, EC50, and PAA) are not controlled via the same molecular interactions. Similar arguments apply if one factor is expressed at relatively higher levels than the other constructs. These conclusions are possible because they rely only on each factor being expressed in biologically significant quantities and are relatively insensitive to the absolute concentration of each factor.

Having obtained evidence that Amax, EC50, and/or PAA can be separately modulated, our next objective was to examine the mechanism. Our approach was to identify those deletions in each factor that eliminate the ability of that factor to augment a given parameter. This tactic also requires only biologically active levels of each factor as opposed to immunochemical quantification of protein expression. For example, the data of MFS vs. MFF in Fig. 5C suggests that the amino terminal half of STAMP is required for the elevation of PAA. The possibility that the inability of MFS to change the PAA could be due to a low expression level of the short form (S) of STAMP and that a similar change in PAA as seen for MFF would occur with “normal” levels of STAMP (S) expression can be eliminated for three reasons. (1) The ability of any combination of three constructs to modulate Amax, EC50, or PAA (as in Table 1 and Figs. 5 and 6) means, by definition, that the final activity is “greater” than that of any two factors alone. Thus, the increase in Amax by the combination of MFS is greater than that of GR (M) and TIF2 (F) and has to be due to net positive effects of expressed STAMP (S). The converse situation of one factor being overexpressed is similarly unable to account for the observed results. Thus the ability of the identical conditions to cause a 2.5-fold larger increase in Amax than seen with the full length factors (FFF) not only proves, by definition, that STAMP (S) is being expressed but also makes the lack of any change in PAA that much more significant. (2) Table 1 shows that there are combinations of constructs in which STAMP (S) is able to modulate the PAA (i.e., FFS and MMS). Similar examples from Table 1 indicate the expression of all of the other constructs when one remembers that a positive value in Table 1 indicates a “positive” change greater than that seen with any two factors. (3) It has been previously documented that STAMP (F and S) (He and Simons; Jr., 2007), TIF2 (F, M, and S) (Voegel et al., 1998, He et al., 2002), and GR (F, M, and S) (Cho et al., 2005a, Cho et al., 2005b) are expressed and are biologically active under similar conditions. In summary, examples in Table 1 of a positive effect on Amax and PAA by at least one ternary complex of every construct of each factor that is greater than any binary combination of the same constructs establishes that sufficient amounts of each construct are being expressed to exert a biological response.

Interestingly, more than one combination of protein sequences for each factor is effective in displaying modulatory activity with any one parameter. The corollary is that one cannot predict the final activity of one collection of protein domains from the activities of the same components in two other, closely related ternary complexes. For example, both FSM and MMM complexes modulate all three parameters (Table 1). One might then predict that MSF would be similarly active; and, one would be wrong. This lack of strict combinatorial behavior suggests that isolated domains are necessary but not sufficient to determine the capacity of the complex to modify a given parameter. Instead, it is likely that the final topology for productive interactions can be molded by the cooperative interactions of a variety of specific protein surfaces, probably via protein-protein induced conformational changes that can be approximated by different combinations of protein sequences. Furthermore, the final activity is sensitive to the gene and cellular environment. For example, the truncated GR407C with full-length TIF2 and STAMP (= MFF) is unable to alter the EC50 for induction of GREtkLUC reporter in CV-1 cells (Table 1) but does decrease the EC50 for induction of the IP6K3 gene in 293 cells (Fig. 2C). This suggests that not only other factors but also target gene DNA sequences may influence the final topology of the GR/TIF2/STAMP complex. This is not unexpected as the DNA sequence can affect GR activity (Meijsing et al., 2009). Similarly, the modulatory activity of the FMM and FMS complexes is not the same in CV-1 (Table 1) and 293 cells (Fig. 6B). This is thus another example of cell-specific differences in steroid-regulated gene expression (So et al., 2007, Biddie et al., 2010). Therefore, the phenomenon of different domains of cofactors and GR independently contributing to the final Amax, EC50, and PAA is likely to be general even though the precise combinations vary with the gene and/or cell type. It is interesting, though, that the EC50 is, in many situations, more sensitive to the removal of individual domains and/or cellular environment (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 6). This suggests that molecular mechanisms controlling the EC50 are often more complex than those for Amax and PAA.

While the present study clearly establishes the ability of defined regions of GR and transcriptional cofactors to selectively modulate Amax, EC50, and/or PAA, it does not directly inform us of the molecular mechanisms involved. Our data implicate different combinations of the protein surfaces of GR, TIF2, and STAMP as being critical determinants. It is, therefore, reasonable to conclude that similar domain-specific interactions with other factors, such as the components of Mediator, histone acetylases and deactylases, and the initial, paused, and elongating complexes of RNA polymerase, also influence the Amax, EC50, and PAA. Identifying these other players and their functional domains will require much further experimentation. However, the present report shows that this is a worthwhile endeavor. Given that the number of possible combinations of interacting protein surfaces greatly exceeds the number of involved proteins, domain-specific interactions offer an attractive mechanism to explain the usually gene-specific responses to a common transcription factor like GR.

Earlier studies with a variety of full-length receptors in different cells suggested that transiently transfected full-length cofactors can modulate Amax, EC50, and PAA independently (Simons; Jr., 2008, Tao et al., 2008, Ong et al., 2010, Lee and Simons; Jr., 2011). A similar alteration of selected parameters in a gene-selective manner has been seen in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) for three endogenous genes when the level of endogenous TIF2 is decreased with added TIF2 siRNA (Luo and Simons; Jr., 2009). In these reported cases, though, it was not possible to determine which domains of each factor modify specific parameters. The results of the present study with GR, TIF2, and STAMP suggest a mechanistic explanation for these previous results: cell- and gene-specific components further adjust the contributions of different domains of identified proteins to regulate the Amax, EC50, and PAA of gene induction by GRs. The present study indicates that that such selective modification of GR transactivation properties is both physiologically relevant, occurs in a variety of cellular systems, and can be localized to defined regions of the involved cofactors. We suspect that the separate modulation of gene induction properties seen in this study is general for many receptors under a variety of conditions with native proteins. These observations are of broader relevance with regard to the well-known, but poorly understood, cell-type specific differences in steroid-regulated gene expression (So et al., 2007, Biddie et al., 2010).

Some combinations of truncated factors have dominant negative activity (i.e., negative values in Table 1) and repress individual parameters to less (for Amax or PAA) or more (for EC50) than seen with the same GR species alone (e.g., the binary GR (S) and STAMP (F) complex and the ternary SSF complex). Such behavior is observed only when the short construct of a factor is present in the complex. This is to be expected due to competition with endogenous factors for complex formation by a species lacking a necessary functional domain(s). However, at least for the ternary complexes, such dominant negative activity is not uniformly seen for all three parameters with a given combination of factors (e.g., MMS, MSF, and SFF). This is additional evidence that each parameter can be individually altered.

The present results provide firm evidence supporting our earlier hypothesis (Simons; Jr., 2008) that different pathways are often employed to regulate Amax, EC50, and/or PAA (Fig. 7). This conclusion has numerous consequences. First, and most obvious, is that many mechanistic details of steroid-regulated gene expression will be missed if one quantitates only the Amax and does not also monitor the EC50 and PAA. The ability of each parameter to be independently controlled argues for the existence of novel factors and pathways that will be detected only if the EC50 of agonists and the PAA of antagonists are quantitated. Such approaches should uncover critical new components of steroid hormone action. Second, the fact that selected domains of transcription factors can uniquely alter one or two induction parameters suggests that small molecules could perform the same function by preferentially interacting with these domains. A conceptual demonstration of this approach has been reported for small molecules that inhibit coactivator peptide binding to the LBD of androgen (Estebanez-Perpina et al., 2007), estrogen (Parent et al., 2008), and thyroid (Hwang et al., 2009) receptors and for point mutations of the GR LBD that appear to perturb particular surfaces of GR-bound TIF2 or Ubc9 to alter Amax, EC50, and/or PAA (Tao et al., 2008, Lee and Simons; Jr., 2011). Third, the possible clinical applications of these conclusions are exciting to contemplate. While genetic engineering to over-express particular cofactor fragments is a theoretically possible approach, a more viable solution may be to search for small, orally active molecules that would inactivate unique domains of selected cofactors. The present studies demonstrate that domain-specific targeting should be feasible. This offers the prospect of dramatically increasing the selectivity, and decreasing the unwanted side effects, of current endocrine therapies, which have been two long-term goals of endocrinologists. Further studies will hopefully yield such candidate small molecules.

Fig. 7.

Model of cofactor modulation of parameters for GR-regulated gene induction. Individual pathways, or interactions with proteins, for altering the levels of gene product can be used such that one, two, or all three of the parameters of Amax, EC50, and PAA are affected. See text for discussion.

Highlights for submission of Awasthi and Simons.

Differential control of steroid-regulated induction by varying Amax, EC50, and PAA

Control of Amax, EC50, and PAA can occur via separate pathways/molecular interactions

Different cofactor domains influence the three different induction parameters

Independent modulation of Amax, EC50, and PAA of exogenous and endogenous genes

Acknowledgements

We thank Yun-Bo Shi (NICHD, NIH) and members of the Steroid Hormones Section for constructive criticism. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDDK.

Abbreviations

- Amax

maximal activity

- Dex

dexamethasone

- DM

dexamethasone-21-mesylate

- DTBP

dimethyl 3,3′-dithiobispropionimidate

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- PAA

partial activity of antisteroids as percent of Amax

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Avenant C, Kotitschke A, Hapgood JP. Glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation modulates transcription efficacy through GRIP-1 recruitment. Biochemistry. 2010;49:972–985. doi: 10.1021/bi901956s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton MC, Shapiro DJ. Transient administration of estradiol-17β establishes an autoregulatory loop permanently inducing estrogen receptor mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:7119–7123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddie SC, John S, Hager GL. Genome-wide mechanisms of nuclear receptor action. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Rogatsky I, Garabedian MJ. MED14 and MED1 differentially regulate target-specific gene activation by the glucocorticoid receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:560–572. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Blackford JA, Jr., Simons SS., Jr. Role of activation function domain 1, DNA binding, and coactivator in the expression of partial agonist activity of glucocorticoid receptor complexes. Biochemistry. 2005a;44:3547–3561. doi: 10.1021/bi048777i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Kagan BL, Blackford JA, Jr., Szapary D, Simons SS., Jr. Glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding domain is sufficient for the modulation of glucocorticoid induction properties by homologous receptors, coactivator transcription intermediary factor 2, and Ubc9. Mol. Endo. 2005b;19:290–311. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Core LJ, Lis JT. Transcription regulation through promoter-proximal pausing of RNA polymerase II. Science. 2008;319:1791–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1150843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Felipe KS, Carter BT, Althoff EA, Cornish VW. Correlation between ligand-receptor affinity and the transcription readout in a yeast three-hybrid system. Biochemistry. 2004;43:10353–10363. doi: 10.1021/bi049716n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estebanez-Perpina E, Arnold AA, Nguyen P, Rodrigues ED, Mar E, Bateman R, Pallai P, Shokat KM, Baxter JD, Guy RK, Webb P, Fletterick RJ. A surface on the androgen receptor that allosterically regulates coactivator binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16074–16079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708036104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor T, Tank DW, Wieschaus EF, Bialek W. Probing the limits to positional information. Cell. 2007;130:153–164. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Simons SS., Jr. STAMP: a novel predicted factor assisting TIF2 actions in glucocorticoid receptor-mediated induction and repression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:1467–1485. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01360-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Szapary D, Simons SS., Jr. Modulation of induction properties of glucocorticoid receptor-agonist and -antagonist complexes by coactivators involves binding to receptors but is independent of ability of coactivators to augment transactivation. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:49256–49266. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JY, Arnold LA, Zhu F, Kosinski A, Mangano TJ, Setola V, Roth BL, Guy RK. Improvement of pharmacological properties of irreversible thyroid receptor coactivator binding inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3892–3901. doi: 10.1021/jm9002704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim FD, Thummel CS. Temporal coordination of regulatory gene expression by the steroid hormone ecdysone. EMBO J. 1992;11:4083–4093. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05501.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul S, Blackford JA, Jr., Chen J, Ogryzko VV, Simons SS., Jr. Properties of the glucocorticoid modulatory element binding proteins GMEB-1 and -2: potential new modifiers of glucocorticoid receptor transactivation and members of the family of KDWK proteins. Mol. Endocrinol. 2000;14:1010–1027. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.7.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul S, Blackford JA, Jr., Cho S, Simons SS., Jr. Ubc9 is a novel modulator of the induction properties of glucocorticoid receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:12541–12549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112330200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kininis M, Isaacs GD, Core LJ, Hah N, Kraus WL. Postrecruitment regulation of RNA polymerase II directs rapid signaling responses at the promoters of estrogen target genes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1123–1133. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00841-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G-S, Simons SS., Jr. Ligand binding domain mutations of glucocorticoid receptor selectively modify effects with, but not binding of, cofactors. Biochemistry. 2011;50:356–366. doi: 10.1021/bi101792d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Duncan KA, Chou H, Chen D, Kohli K, Huang C-F, Stallcup MR. A somatic cell genetic method for identification of untargeted mutations in the glucocorticoid receptor that cause hormone binding deficiencies. Mol. Endocrinol. 1995;9:826–837. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.7.7476966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Knappenberger KS, Kack H, Andersson G, Nilsson E, Dartsch C, Scott CW. A homogeneous in vitro functional assay for estrogen receptors: coactivator recruitment. Mol. Endocrinol. 2003;17:346–355. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard DM, O'Malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: judges, juries, and executioners of cellular regulation. Mol Cell. 2007;27:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]