Abstract

Impairment of host immunity, particularly CD4+ T cell deficiency, presents significant complications for vaccine immunogenicity and efficacy. CD40 ligand (CD40L or CD154), a member of the tumor necrosis factor superfamily (TNFSF), is an important co-stimulatory molecule and, through interactions with its cognate receptor CD40, plays a pivotal role in the generation of host immune responses. Exploitation of CD40L and its receptor CD40 could provide a means to enhance and potentially restore protective immune responses in CD4+ T cell deficiency. To investigate the potential adjuvanticity of CD40L, we constructed recombinant plasmid DNA and adenoviral (Ad) vaccine vectors expressing murine CD40L and the mycobacterial protein antigen 85B (Ag85B). Co-immunization of mice with CD40L and Ag85B by intranasal or intramuscular prime-boosting led to route-dependent enhancement of the magnitude of vaccine-induced circulating and lung mucosal CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in both normal (CD4-replete) and CD4+ T cell deficient animals, including polyfunctional T cell responses. The presence of CD40L alone was insufficient to enhance or restore CD4+ T cell responses in CD4-ablated animals; however, in partially-depleted animals, co-immunization with Ag85B and CD40L was capable of eliciting enhanced T cell responses, similar to those observed in normal animals, when compared to those given vaccine antigen alone. In summary, these findings show that CD40L has the capacity to enhance the magnitude of vaccine-induced polyfunctional T cell responses in CD4+ T cell deficient mice, and warrants further study as an adjuvant for immunization against opportunistic pathogens in individuals with CD4+ T cell deficiency.

1. Introduction

Impaired immune function, including CD4+ T cell deficiency, can drastically affect the ability of an individual to mount effective immune responses following vaccination. There are growing numbers of individuals with defects in CD4+ T cell numbers and functions due to HIV infection, age, malignancy, or other immunosuppressive factors [1]. CD4+ T cell deficiency can lead to increased risk of opportunistic infections, increased morbidity and mortality of many primary infections, and decreased efficacy of immunization. It is, therefore, of interest to direct efforts towards developing immunization strategies to elicit robust vaccine-induced immune responses in the context of CD4+ T cell deficiency.

With a demonstrated role in the generation and promotion of host immune responses, the CD40:CD40L ligand (CD40L) pathway provides a potential means of manipulation and enhancement of vaccine-induced immunity. CD40 is a member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily (TNFRSF) and is constitutively expressed on human and mouse B cells, dendritic cells, and monocytes/macrophages [2-3]. CD40L, a tumor necrosis factor superfamily member (TNFSF), is primarily expressed as a costimulatory molecule on the surface of activated T cells, particularly CD4+ T cells [2-4]. Like other TNFSF members, CD40L has been shown to be crucial for expansion and survival of T, B, and dendritic cells during the initial phases of the immune response [5-12]. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of exogenous CD40L as a vaccine adjuvant to promote increased T cell proliferation and effector functions, including T cell polyfunctionality and cytokine production, and to polarize cellular and humoral immune responses towards a Th1 phenotype [13-20].

While experimental evidence indicates that CD40L may serve as a vaccine adjuvant, its capacity to enhance immune responses under conditions of immunodeficiency is less clear. It has been postulated that the additional CD40 stimulation provided by exogenous CD40L could act as a surrogate for CD4+ T cell help [21]. In pre-clinical trials, the use of exogenous CD40L with a target antigen led to improved memory responses and overcame age-related immune defects [22]. Previous studies from our laboratory and by others have demonstrated, in murine models of CD4-depletion, that immunization with CD40L and vaccine antigens increased antigen-specific CD8+ T cell numbers, IFN-γ production, and humoral responses [23-24].

As these earlier studies did not specifically address CD4+ T cell responses, we designed the current study to investigate whether CD40L had the capacity to enhance both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses in the context of CD4+ T cell immunodeficiency. To that end, we constructed plasmid DNA and Ad vaccine vectors encoding murine CD40L along with the mycobacterial vaccine antigen 85B (Ag85B). Ag85B is a major secretory protein in actively-replicating M. tuberculosis, possesses the mycolyltransferase activity necessary for mycobacterial cell wall formation, and has been shown to be highly immunogenic in individuals with latent or active tuberculosis [25-28]. Heterologous prime-boost immunization has been shown by ourselves and others to induce both quantitatively and qualitatively superior T cell responses of the Th1 phenotype, including “polyfunctional” T cell responses, as compared to conventional or single vector-based immunization strategies [29-32]. We therefore evaluated our vaccine vectors in prime-boost combinations, either by systemic or mucosal routes, in both normal (CD4-replete) and immunodeficient mouse models. Our studies indicate that CD40L-mediated enhancement of vaccine immunogenicity is route-dependent and that CD40L can enhance vaccine-induced circulating and lung mucosal immunity in both normal and CD4+ T cell deficient animals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Vaccine Vectors

Nucleotide sequences for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Erdman strain Antigen 85B (Ag85B) (GenBank Acc. No. X62398) and for Mus musculus CD40 ligand (GenBank Acc. No. NM_011616) were codon-optimized using Java Codon Optimization Tool (http://www.jcat.de) and manufactured by GenScript. Individual coding sequences were cloned into the dual-expression vector pBudCE4.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California) under the CMV (Ag85B) or EF-1α (CD40L) promoters. The CD40L coding sequence was also cloned into the pHIS plasmid (Coley Pharmaceutical Group, Wellesley, Massachusetts). A pHIS plasmid encoding Ag85B was previously prepared in this laboratory using standard molecular cloning techniques. Plasmid construct identities and orientations were confirmed by restriction digest and sequencing. Plasmid DNA was prepared using Endo-Free MegaPrep kits (QIAgen, Gaithersburg, Maryland). Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CD40L constructs were prepared by cloning the Ag85B and CD40L coding sequences into Gateway® pENTR2B entry and pAd/CMV/V5-DEST destination vectors (Invitrogen). Adenovirus type 5 constructs were purified from pAd-transfected 293A cell extracts by anion-exchange chromatography and CsCl density gradients. Adenovirus purity and identity was confirmed by PCR of viral DNA.

2.2 Generation of mBMDCs and IL-12p70 ELISA

Murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (mBMDCs) were generated following harvest of bone marrow from mouse femurs and tibias. Bone marrow cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone, Thermo Fisher Scientific), 12.5 ng/mL mGM-CSF, 12.5 ng/μL mIL-4, 10 mM HEPES, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis Missouri). All media reagents were purchased from Gibco unless otherwise specified. mBMDCs were harvested on day 6-7 and maturity was assessed by flow cytometry for MHC II, CD80/86, CD11c, and DEC205 surface markers. mBMDCs were transduced with Ad vaccine vectors at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 250 in triplicate. Cell supernatants were collected at 18, 24, and 48 hrs. post-transduction and used to measure IL-12p70 content using a DuoSet Mouse IL-12p70 ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota) according to manufacturer's instructions. Sample absorbances at 450 and 540 nm were measured using a Syngery HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, Vermont).

2.3 Animals

Six to eight week old specific pathogen-free female BALB/c mice were purchased from Charles River (North Carolina) and housed in the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center (LSUHSC) Animal Care Facility. All procedures were approved by the LSUHSC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). All invasive procedures were performed under anesthesia with a mixture of KetaThesia (ketamine HCl, 100 mg/mL, Butler Animal Health Supply, Dublin, Ohio) and xylazine (10 mg/mL) diluted eight-fold in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco, Invitrogen).

2.4 CD4+ T cell Deficient Murine Models

CD4+ T cell deficient murine models were established by intraperitoneal injection of rat anti-mouse CD4 monoclonal antibody (GK1.5) (Taconic, Hudson, New York) at 0.1 mg (CD4-ablated murine model) or 0.02 mg (CD4-depeleted murine model) in 200 μL PBS. CD4+ T cell depletion was initiated three days prior to immunization with DNA vaccines and maintained by weekly injections thereafter.

2.5 Immunizations

Animals were immunized with plasmid DNA and adenoviral vaccine vectors encoding both Ag85B and CD40L or Ag85B alone according to a DNA or prime-boost immunization protocols (Table 1). DNA immunizations were given as a cocktail of DNA vaccines encoding Ag85B or CD40L or as a single DNA vaccine encoding both Ag85B and CD40L by intramuscular injections of 30 μg plasmid DNA into each tibialis muscle (60 μg total) followed by immediate electroporation with 2 pulses at 150 volts using an ECM 830 Electroporation System and caliper electrode (BTX - Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, Massachusetts) delivered at weeks 0 and 3. Booster immunizations were administered as cocktails of Ad vaccines in PBS (1 × 109 PFUs Ad consisting of 5 × 108 PFUs Ad-Ag85B and 5 × 108 PFUs Ad-CD40L or Ad/CMV) by intranasal administration (20 μL per animal) or intramuscular injection into the quadriceps of either hind limb (100 μL per animal) routes at week 6.

Table 1.

DNA and Prime-Boost Immunization Protocols

| Group | Week 0 | Week 3 | Week 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Immunization | |||

| Ag85B | pHIS-Ag85B | pHIS-Ag85B | – |

| Ag85B + CD40L (cocktail of DNA Vaccines) | pHIS-Ag85B pHIS-CD40L |

pHIS-Ag85B pHIS-CD40L |

– |

| Ag85B | pBud-Ag85B | pBud-Ag85B | – |

| Ag85B + CD40L (single co-expressing DNA Vaccine) | pBud-Ag85B/CD40L | pBud-Ag85B-CD40L | – |

| Prime-Boost Immunization | |||

| Ag85B | pBud-Ag85B | pBud-Ag85B | Ad-Ag85B Ad-CMV |

| Ag85B + CD40L | pBud-Ag85B-CD40L | pBud-Ag85B-CD40L | Ad-Ag85B Ad-CD40L |

DNA vaccines were administered by intramuscular injection followed by electroporation as described in Materials and Methods, such that each animal received a total of 60 μg of designated DNA vaccines at weeks 0 and 3. Ad vaccines were given at week 6 either by the intranasal (IN) or intramuscular (IM) routes as described in Materials and Methods, such that each animal received a cocktail comprising 5 × 108 PFU of the Ad vaccine listed above. See figure legends for specific details within each experiment.

2.6 Isolation of Lymphocytes

At three or six weeks post-immunization, animals were euthanized, and spleens and lung-associated lymph nodes (deep cervical as well as anterior and poster mediastinal LNs) were isolated by gross dissection. Tissues were processed into single-cell suspensions in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 20 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, 50 U/mL penicillin, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10% FCS (Hyclone). All media reagents were purchased from Gibco unless otherwise specified. Red blood cell lysis was performed using RBC Lysing Buffer (Sigma-Aldrich).

2.7 Peptides

Synthetic peptide oligomers for CD4 epitopes in Ag85B, the 20-mer p99 (TFLTSELPQWLSANRAVKPT) and the 18-mer p262 (HSWEYWGAQLNAMKGDLQ), or the CD8 epitope, the 9-mer CTL8 (MPVGGQSSF), were used to stimulate antigen-specific responses in IFN-γ ELISpot and ICS assays. All peptides were synthesized by Genscript (Piscataway, NJ).

2.8 Interferon gamma (IFN-γ) ELISPOT

IFN-γ ELISpot assays were performed using 96-well Multiscreen TM-IP plates (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts) and Mabtech reagents for ELISpot assay of mouse interferon-γ (Mariemont, Ohio) according to manufacturer's protocols. Cells were stimulated with CD4+ or CD8+ peptides at 2 μg/mL. Spots were developed using BCIP/NBT substrate (Moss Substrates, Pasadena, Maryland) and enumerated with an AID-ELISPOT counter (AutoImmun Diagnostika GmbH, Strasburg, Germany). Data are presented as spot-forming cells (SFC) per million cells.

2.9 Intracellular cytokine staining (ICS)

For ICS assays, 1-2 × 106 isolated lymphocytes were stimulated with 2 μg/mL anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody (Caltag, Invitrogen) and 5 μg/mL CD4 or CD8 epitope peptides at 37°C for 2 hrs, treated with 0.1 μL/well BD GolgiPlug Protein Transport Inhibitor (BD Pharmigen, San Diego, California), and incubated at 37°C for an additional 4 hrs. Cells were stained, washed, fixed and permeablized using a BD CytoFix/CytopermTM Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (BD Biosciences, San Diego, California). Fluorochrome antibodies used for staining included CD3e-Pacific Blue, CD4-FITC, CD8-PE-Cy5, CD4-FITC, IFN-γ-APC, IL-2-PE, and TNF-α-PE-Cy7 (BD Pharmigen). Samples were acquired on a BD LSR II system. Data were analyzed using FlowJo Software version 8.8.6 (Tree Star, Ashland, Oregon). For analysis, lymphocyte populations were initially identified by forward-scatter (size) and side-scatter (granularity) profiles. Lymphocytes positive for CD3 were subsequently sorted into CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ subsets. Cytokine-secretion was measured in these T cell subsets.

2.10 Statistical Analysis

ANOVA and Student's t-test were used to determine statistical significance. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Construction and evaluation of recombinant plasmid DNA and Ad vaccine vectors expressing CD40L and Ag85B

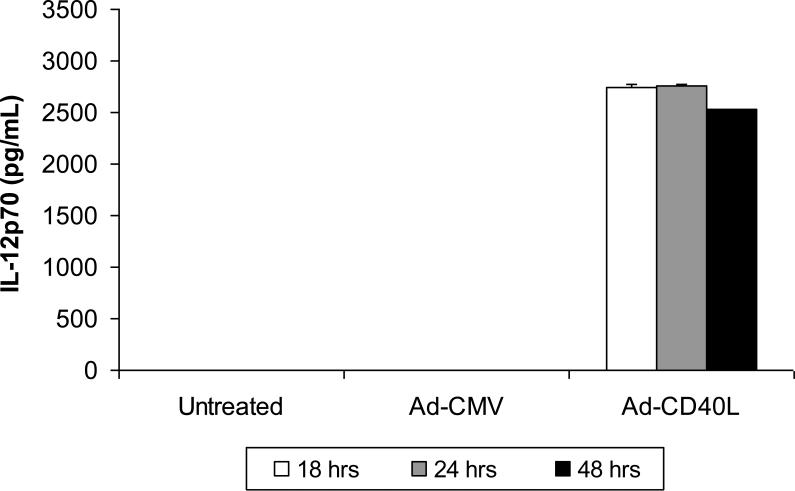

Recombinant plasmid DNA vectors expressing the mycobacterial protein Ag85B and CD40L in single- (pHIS) and dual-expression (pBudCE4.1) plasmid vector systems and recombinant adenovirus type 5 vaccine vectors expressing Ag85B and CD40L transgenes were designed and constructed as described above. The expression of biologically-active CD40L was shown by induction of IL-12p70 in murine bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) transduced with vectors encoding CD40L but not control vectors (Fig. 1). Cross-linking of CD40 in DCs by CD40L stimulation is known to induce robust IL-12 production [33].

Figure 1. Functional expression of vector-encoded CD40L in BMDCs.

Murine BMDCs were infected with control vector (Ad-CMV) or Ad-CD40L at an MOI of 250. Untreated murine BMDCs served as transduction and negative controls. Cell culture supernatants collected at 18, 24, and 48 hours post-transduction were tested using an IL-12p70 ELISA, as described in Materials and Methods. As anticipated, only BMDCs transfected with the Ad-CD40L demonstrated induction of IL-12p70 expression. Data shown are mean ± SEM from two independent experiments performed in triplicate.

3.2. CD40L expression enhances the immunogenicity of DNA vaccination

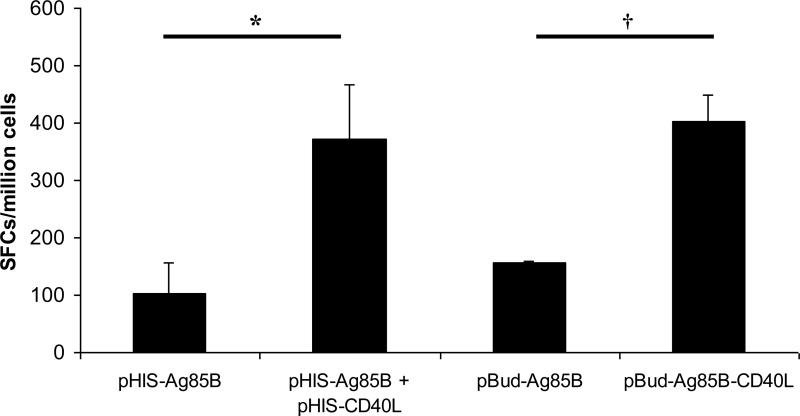

Initial immunization experiments were designed to compare the effects of CD40L on antigen-specific T cell responses when delivered either as a cocktail of DNA vaccines or co-expressed with vaccine antigen in a single DNA vaccine. As detailed in Table 1, mice were immunized either with DNA vaccines encoding Ag85B alone, a cocktail of DNA vaccines encoding either Ag85B or CD40L, or a single DNA vaccine encoding both Ag85B and CD40L. Circulating T cell responses were assessed in IFN-γ ELISpot assays at three weeks post-immunization. Mice immunized with Ag85B and CD40L, either as a cocktail of DNA vaccines or in a single DNA vaccine, demonstrated nearly four-fold increases in numbers of CD8+ T cells secreting IFN-γ compared to those immunized with Ag85B alone (Fig. 2). CD4+ T cell responses elicited following stimulation with the p99 and p262 peptides were also analyzed in these mice, but were generated only at low levels following DNA immunization alone (data not shown). Additional controls included mice immunized with pHIS, pHIS-CD40L, pBudCE4.1, or pBud-CD40L control vectors, in which Ag85B-specific immune responses were not detected (data not shown). These results indicate that immunization with either a cocktail of pHIS-Ag85B and pHIS-CD40L vaccines or with the pBud-Ag85B-CD40L vaccine were of similar immunogenicity for CD8+ T cell responses. It was therefore concluded that dual-expression pBudCE4.1-based plasmids represented a more economical and potentially more efficient vector system for use in further studies involving more immunogenic DNA/Ad prime-boost immunization strategies.

Figure 2. CD40L enhances circulating CD8+ T cell responses to Ag85B expressed in DNA vaccines.

Female BALB/c mice of 6-8 weeks of age were immunized twice either with a single DNA vaccine expressing Ag85B (pHIS-Ag85B or pBud-Ag85B), a cocktail of DNA vaccines (pHIS-Ag85B and pHIS-CD40L), or a single DNA vaccine expressing both Ag85B and CD40L (pBud-Ag85B-CD40L). Mice were sacrificed at 3 weeks post-immunization and splenocytes were isolated for use in IFN-γ ELISpot assays. Data shown are mean numbers of spot-forming cells (SFCs) ± SEM for pooled splenocyte samples within each vaccine group. Data represent inter-sample variations of pooled samples from one experiment and are representative of three such experiments performed. n = 4-6. *P = 0.013. †P < 0.01.

3.3. Prime-boost immunization with Ag85B and CD40L demonstrates route-dependent enhancement of circulating immunity

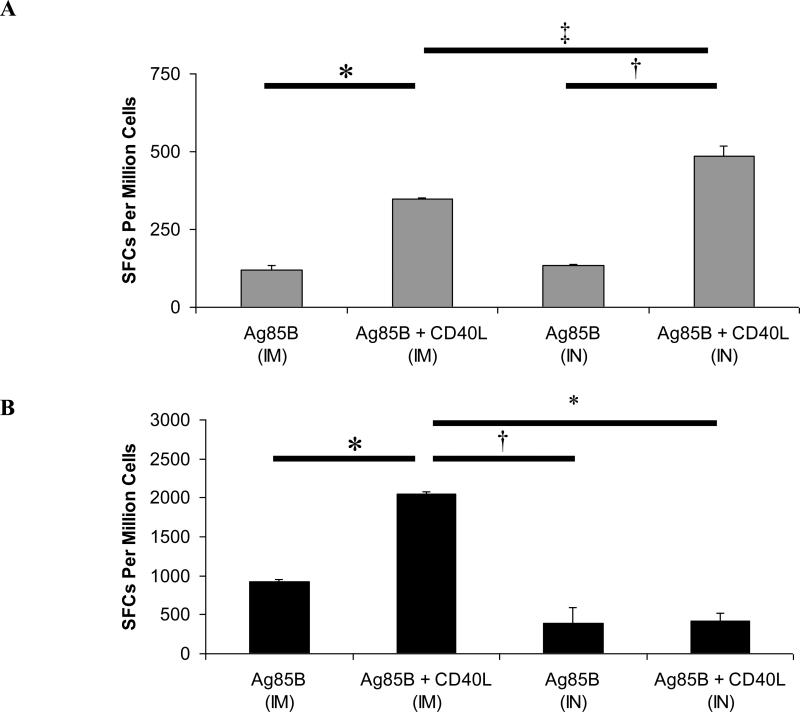

DNA vaccine vectors were used to prime mice using two rounds of immunization at an interval of three weeks followed by boosting with a cocktail of recombinant Ad vaccine vectors encoding Ag85B, with or without CD40L, three weeks later. Prime-boost immunization protocols are detailed in Table 1. Intramuscular and intranasal routes of boosting were compared in order to evaluate their capacity to generate circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to the vaccine antigen.

We compared circulating T cell responses following intramuscular or intranasal boosters given six weeks after the initial DNA immunizations (Fig. 3). The route of boosting did not appear to affect the magnitude of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell responses elicited following immunization with Ag85B alone (Fig. 3A). When CD40L was included in either immunization protocol, numbers of IFN-γ-secreting CD4+ T cells that were generated were significantly increased. However, intranasal boosting with Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CD40L was superior to intramuscular boosting for induction of circulating Ag85B-specific CD4+ T cell responses. In contrast, booster immunization with Ag85B via the intramuscular route favored the induction of circulating CD8+ T cell responses (Fig. 3B). Intramuscular boosting with both Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CD40L strongly enhanced the numbers of responding IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ T cells. However, intranasal boosting with Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CD40L had no discernable influence on circulating CD8+ T cell responses.

Figure 3. Intramuscular or intranasal prime-boost immunization with CD40L demonstrates route-dependent enhancement of circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses.

Female BALB/c mice of 6-8 weeks of age were prime-boost immunized with Ag85B and CD40L vaccines or Ag85B vaccine alone (see Table 1). Booster immunizations were administered as a cocktail of either Ad-Ag85B + Ad-CD40L or Ad-Ag85B + Ad-CMV via intramuscular (IM) or intranasal (IN) routes. Six weeks post-immunization, splenocytes were isolated and CD4+ T cell responses (A) and CD8+ T cell responses (B) were assayed by IFN-γ ELISpot. Data shown are mean SFCs ± SEM within each vaccine group (n = 6-8), and represent inter-sample variations of pooled cells from one experiment that is representative of three such experiments performed. n = 6-8. *P < 0.001. †P < 0.005. ‡P = 0.022.

These results indicate that intranasal boosting with heterologous vaccine vectors expressing vaccine antigen and CD40L generates superior CD4+ T cell responses in the circulation, suggesting that events downstream of delivery of CD40L to the pulmonary tissues may favor induction of CD4+ T cell responses.

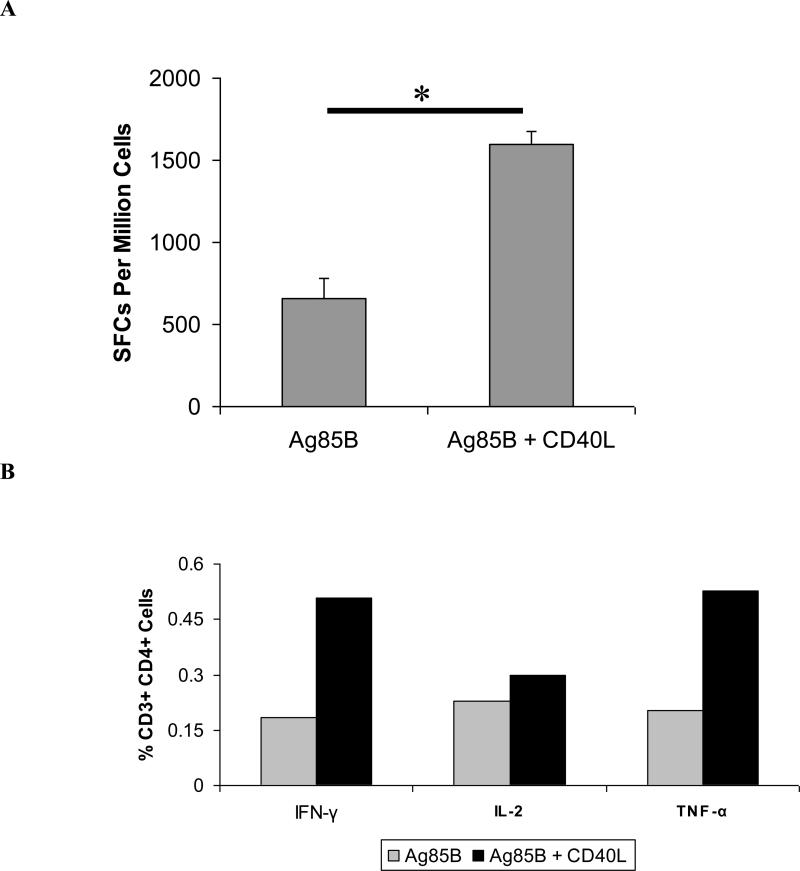

3.4. CD40L enhances pulmonary mucosal CD4+ T cell responses following prime-boost immunization by the intranasal route

We next examined pulmonary mucosal T cell responses generated following intranasal boosting with Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CD40L vaccines in DNA-primed mice. Lymph nodes, including the deep cervical and mediastinal nodes, were collected for assay six weeks after Ad boosting by the intranasal route. Local immunization with CD40L led to increases in both the magnitude and polyfunctionality of CD4+ T cell responses in lung-associated lymph nodes, with greater than two-fold increases in numbers of Ag85B-specific, IFN-γ-secreting pulmonary CD4+ T cells measured by IFN-γ ELISpot (Fig. 4A). Intracellular cytokine staining confirmed these findings and further showed that IFN-γ- and TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cells were the populations that were most prominently increased following immunization with Ag85B and CD40L (Fig. 4B), likely indicating a CD40L-mediated enhancement of effector function. Splenocyte populations from mice boosted intranasally with CD40L also contained significantly greater numbers of Ag85B-specific IFN-γ-, IL-2-, or TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cells than animals given Ag85B alone; however, consistent with our earlier findings, no significant differences were observed in pulmonary mucosal CD8+ T cell responses (data not shown).

Figure 4. Immunization with Ag85B and CD40L increases the magnitude of pulmonary CD4+ T cell responses.

Lung-associated lymph nodes were harvested from mice primed with DNA vaccines and boosted intranasally with Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CD40L or with Ad-Ag85B alone at six weeks post-immunization. (A) CD4+ T cell responses in lung-associated lymph nodes were measured by IFN-γ ELISpot. Data shown are mean SFCs ± SEM for pooled cell samples within each vaccine group and represent inter-sample variations of pooled cells from one experiment that is representative of three such experiments performed. *P < 0.005. (B) Intracellular cytokine staining of CD4+ T cells from lung-associated lymph nodes. Percentages represent frequencies of cytokine-secreting cells within the total CD3+ CD4+ parent cell population. A minimum of 250,000 cells were acquired for each vaccine group. Data are shown for one experiment using pooled lymph node cell samples within each vaccine group (n = 4-8) and are representative of four such experiments.

3.5 Establishment of murine models of CD4+ T cell deficiency

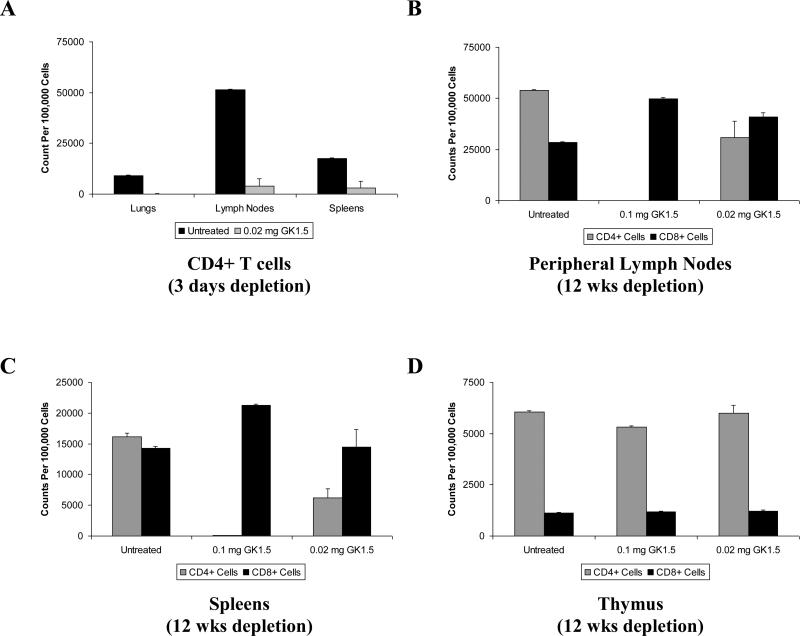

It has been established, by ourselves and others, that the rat anti-mouse CD4 monoclonal antibody GK1.5 can be used to effectively deplete BALB/c mice of CD4+ T cells [23,24,34,35]. We evaluated different doses of GK1.5 by weekly intraperitoneal injections in attempts to establish models of CD4+ T cell deficiency in order to study the effects of CD40L on vaccine-induced immunity in these animals (Fig. 5). Three days after initial administration of GK1.5, the CD3+CD4+ cell populations in the lungs, lymph nodes, and spleens were dramatically reduced in number (Fig. 5A). With time, the CD4+ cell counts in these tissues stabilized, resulting in a state of “CD4-depletion,” with a loss of approximately 40-60% of tissue-resident CD4+ T cells in a mouse given 0.02 mg GK1.5/week, or a state of “CD4-ablation,” in mice given 0.1 mg GK1.5/week, where CD4+ T cell populations were virtually eliminated (Fig. 5B, 5C). These levels of depletion were maintained during twelve weeks of weekly GK1.5 administration, the maximum duration of these experiments. GK1.5-mediated CD4 depletion did not impair the production of naïve T cells as demonstrated by cell counts in the thymus (Fig. 5D), while peripheral CD8+ T cell counts were not adversely affected by GK1.5 administration.

Figure 5. GK1.5-mediated depletion of CD4 T cells from lymphoid tissues of BALB/c mice.

Female BALB/c mice of 6-8 weeks of age were treated with the anti-mouse CD4 monoclonal antibody GK1.5 at doses of 0.1 mg or 0.02 mg per mouse by weekly intraperitoneal injection. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell numbers were measured in tissues from individual mice by flow cytometry following staining with fluorescent-labeled anti-mouse CD3, CD4, and CD8 mAbs. A minimum of 100,000 cells were acquired for each sample group. (A) Measurement of CD3+ CD4+ lymphocytes in lung tissues, lymph nodes, and spleens at three days after injection of 0.02 mg/mouse GK1.5. Mean cell counts of CD3+ CD4+ and CD3+ CD8+ lymphocyte subsets from (B) spleens, (C) peripheral lymph nodes, or (D) thymuses, after 12 weeks of GK1.5-mediated CD4+ T cell depletion. Data shown represent mean cell counts ± SEM from individual experiments (n = 3-5) that are representative of four such experiments performed.

3.6 Immunization with Ag85B and CD40L enhances vaccine-induced immune responses in CD4-depleted but not CD4-ablated animals

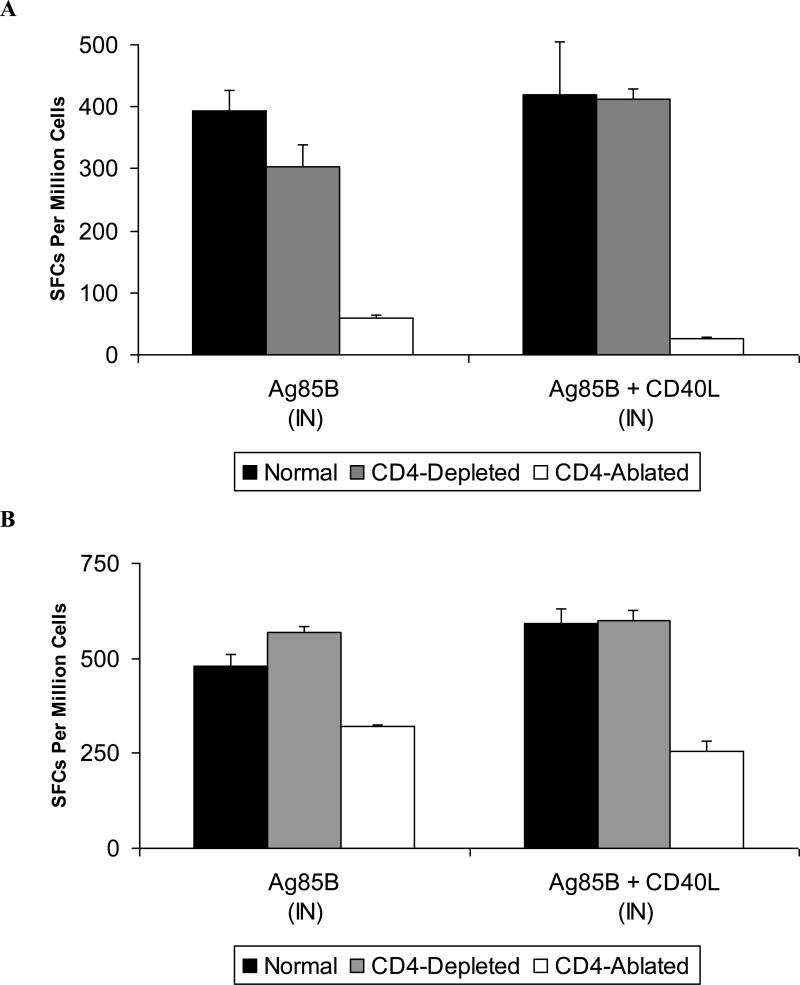

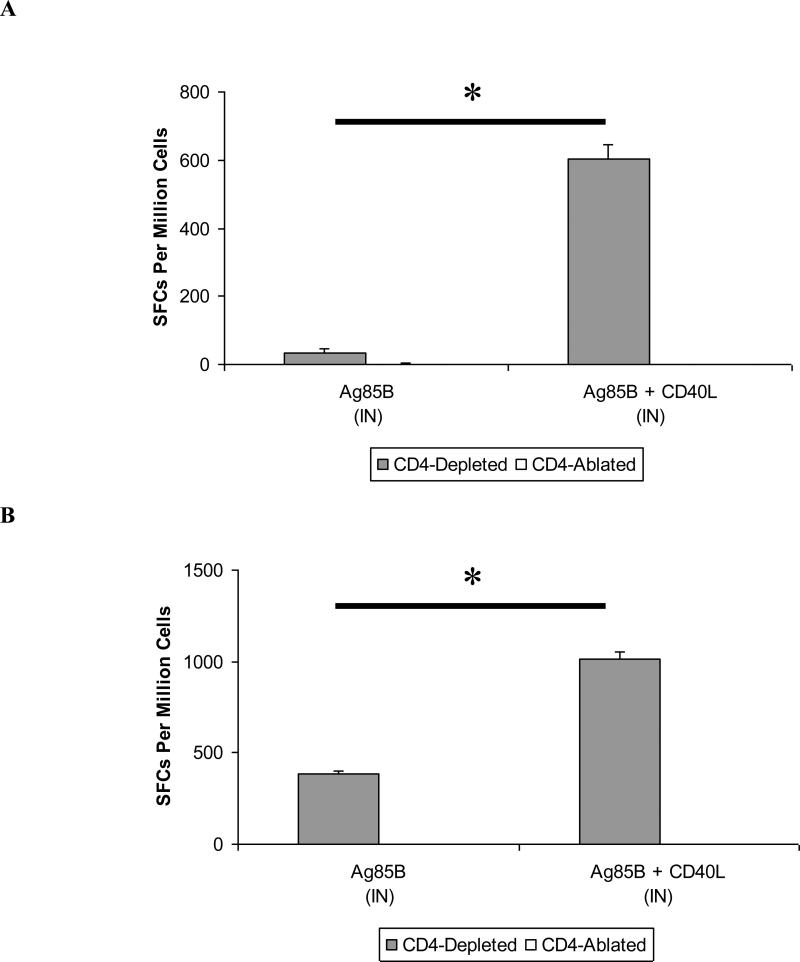

Having shown that CD40L to enhance vaccine-induced immunity in normal (CD4-replete) animals, we next examined its capacity to augment antigen-specific T cell responses in our CD4-deficient murine models. CD8+ T cell responses directed at Ag85B were detected in both CD4-depleted and CD4-ablated animals, however CD4-ablation resulted in significant reductions in antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in the circulation and lung-associated tissues (Fig. 6). CD40L did not significantly enhance CD8+ T cell responses in either CD4-depleted or CD4-ablated animals.

Figure 6. Generation of vaccine-induced CD8+ T cell responses was unimpaired in CD4+ T cell deficiency but diminished in CD4-ablated animals.

Female BALB/c mice of 6-8 weeks of age were either left untreated, CD4-depleted with 0.02 mg GK1.5, or CD4-ablated with 0.1 mg GK1.5 given at three days prior to immunization and weekly thereafter. Six weeks after intranasal booster immunization with Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CD40L or Ad-Ag85B and Ad-CMV, mice were sacrificed and tissues harvested for isolation of lymphocytes. Circulating (A) or lung-associated lymph node (B) CD8+ T cell responses against Ag85B were measured by IFN-γ ELISpot. Data shown are mean SFCs ± SEM for pooled samples within each vaccine group (n = 5-8) and represent inter-sample variations of pooled cells from a single experiment that is representative of three such experiments that were performed.

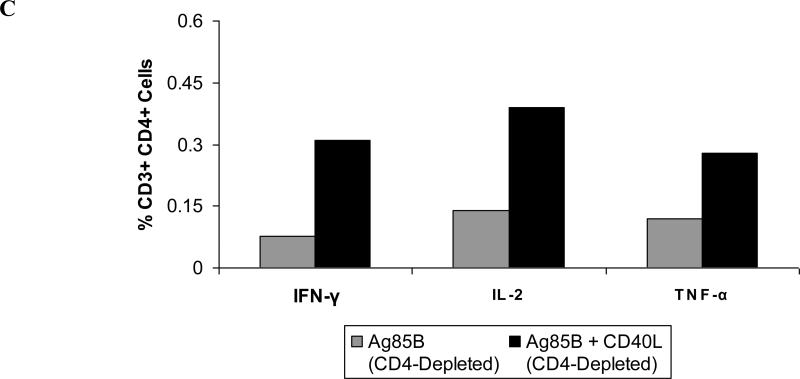

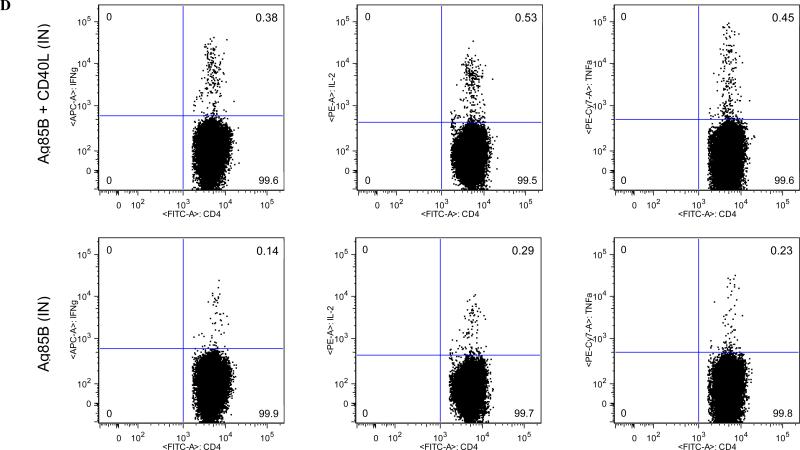

As anticipated, Ag85B-specific CD4+ T cell responses were not detected in the ablated animals (data not shown). It appears, therefore, that vector-directed delivery of CD40L is unable to “replace” missing CD4+ T cell activity in severely-depleted mice, despite its demonstrated adjuvant activities. In contrast, in CD4-depleted animals, CD40L retained potent adjuvant activity. Both circulating and lung-associated Ag85B-specific CD4+ T cell responses were significantly increased following immunization with Ag85B and CD40L (Fig. 7A, 7B). Levels of IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α secretion by pulmonary mucosal CD4+ T cells were also increased in these animals as demonstrated by flow cytometry (Fig. 7C, 7D). While normal (CD4-replete) animals demonstrated the most pronounced increases in vaccine-induced IFN-γ- and TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cell populations (Fig. 4B), percentages of CD4+ T cells secreting IFN-γ, IL-2, or TNF-α were elevated in the CD4-depleted animals. This suggests that CD40L not only enhances T cell function, but also potentially promotes the proliferation and survival of these cell populations.

Figure 7. CD40L enhances vaccine-induced CD4+ T cell responses in CD4-depleted but not CD4-ablated animals.

Female BALB/c mice of 6-8 weeks of age were either left untreated, CD4-depleted with 0.02 mg GK1.5, or CD4-ablated with 0.1 mg GK1.5 at three days prior to immunization and weekly thereafter. Six weeks following intranasal booster immunizations with cocktails of Ad vaccine vectors, animals were sacrificed, and spleens and lung-associated lymph nodes were harvested for cell isolation. (A) Circulating CD4+ T cell responses as measured by IFN-γ ELISpot. * P < 0.005. (B) Pulmonary mucosal CD4+ T cell responses measured in pooled cells from lung-associated lymph nodes by IFN-γ ELISpot. *P < 0.005. Data shown are mean SFCs ± SEM within each vaccine group (n = 5-8), and represent inter-sample variations of pooled cells from one experiment that is representative of three such experiments performed. (C) Intracellular cytokine staining of lung-associated lymph node CD4+ T cells from CD4-depleted animals. (D) Representative FACS plots for cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cells isolated from lung-associated lymph nodes. Data are shown for IFN-γ (left-hand side panels), IL-2 (center), and TNF-α (right). Percentages represent frequencies of specific cytokine-secreting cells within the total CD3+ CD4+ parent population. A minimum of 250,000 cells were acquired for each vaccine group. Data shown represent pooled lymph node cell samples within each vaccine group (n = 5-8) for one experiment that is representative of three such experiments that were performed.

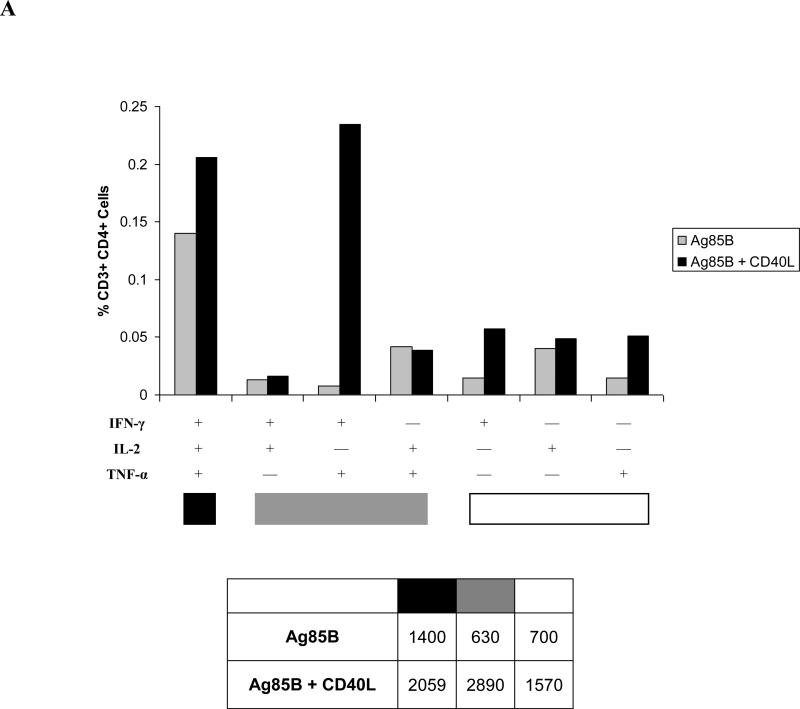

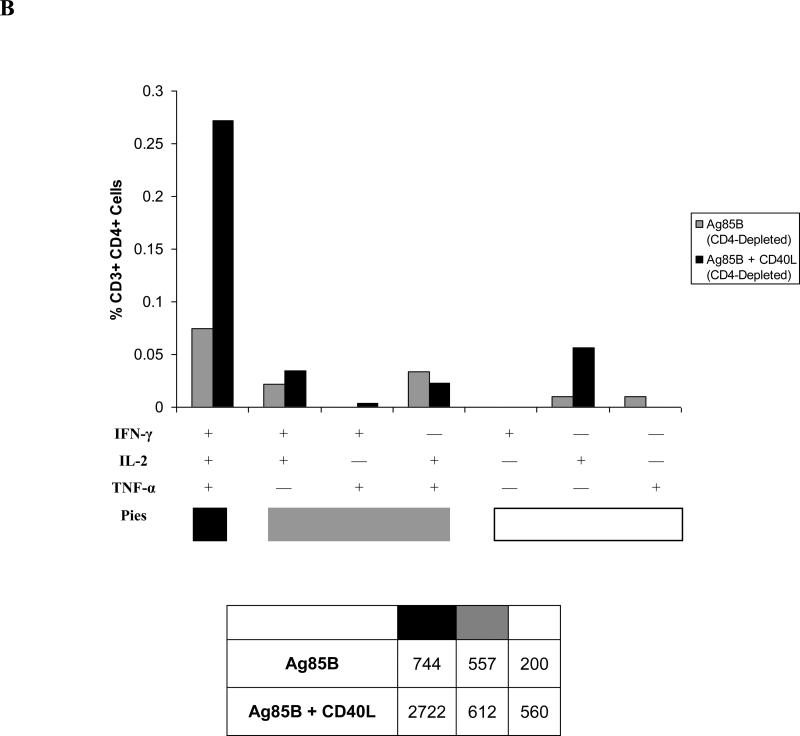

CD4+ T cell responses were further analyzed to determine whether different cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cell subsets were induced in response to exogenous CD40L stimulation. Analyses in normal animals indicated that the increases that were seen in IFN-γ- and TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cell numbers (Fig. 4B) correlated with increases in the percentages of the polyfunctional IFN-γ/TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cell subset and elevated proportions of IFN-γ/IL-2/TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cells (Fig. 8A). In contrast, the only cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cell subsets detected at appreciable levels in CD4-depleted animals were those secreting IL-2, with the IFN-γ/IL-2/TNF-α polyfunctional CD4+ T cell population predominating in mice given CD40L, implying that CD40L enhanced the induction of antigen-specific T cells (Fig. 8B). However, the apparent “loss” of T cell populations, previously observed in normal animals, may be a consequence of periodic GK1.5 administration rather than a failure to induce these populations. Similar profiles of polyfunctional T cells were observed in circulating CD4+ T cell populations following delivery of CD40L by intranasal prime-boost immunization (data not shown). In both normal and CD4-depleted animals, immunization with CD40L promoted increased frequencies of polyfunctional CD4+ T cells. The inclusion of CD40L maintained the immunogenicity of the vaccine protocols that were developed in these studies, despite lower numbers of CD4+ T cells in the depleted mice.

Figure 8. Immunization with CD40L leads to increases in polyfunctional pulmonary T cell populations in both normal and CD4-depleted animals.

Cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cell populations identified by intracellular cytokine staining six weeks after intranasal booster immunizations were further analyzed to determine the effects of CD40L on the generation of polyfunctional CD4+ T cell subsets assayed in lung-associated lymph nodes from (A) normal mice and (B) CD4-depleted mice. Percentages represent frequencies of each CD4+ T cell subset within the parent CD3+ CD4+ cell population for one experiment using pooled cells from within each vaccine group (n = 5-8), and are representative of three such experiments. Tables under each graph list absolute numbers of Ag85B-specific cytokine-secreting CD4+ T cell subsets per 1 × 106 CD3+ CD4+ cells in each vaccine group.

4. Discussion

In these studies, we have demonstrated that CD40L is a potent adjuvant capable of enhancing both the magnitude and polyfunctionality of vaccine-induced circulating and lung mucosal CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses of the Th1 phenotype. Moreover, vector-directed CD40L also exhibited route-dependent adjuvant activity. Intramuscular booster immunizations with vectors encoding CD40L appeared to preferentially increase CD8+ T cell responses whereas intranasal boosting selectively enhanced CD4+ T cell responses. In immunodeficient animals, prime-boost immunization with Ag85B and CD40L led to enhanced T cell responses, particularly CD4+ T cell immune responses, extending our earlier studies concerning the adjuvanticity of CD40L under conditions of immunodeficiency [23-24].

Our studies using DNA vaccines indicate that vector-directed CD40L is effective as an adjuvant when delivered in a cocktail of DNA constructs or when co-expressed in a single DNA vaccine. Intramuscular immunization with a cocktail of pHIS-Ag85B and pHIS-CD40L vaccines, or with the pBud-Ag85B-CD40L vaccine, led to significant increases in numbers of vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells. Moreover, delivery of Ag85B and CD40L in a single DNA vaccine was of similar immunogenicity to delivery as a cocktail. It is well-established that DNA vaccines can transduce DCs, leading to cross-presentation of antigens in muscle tissue [37-39], while CD40L signaling aids DC maturation as well as macrophage/monocyte and B cell development [40]. Although the precise mechanisms underlying of CD40L-mediated immune enhancement are unclear, our findings suggest that CD40L adjuvant activity is not dependent on tandem expression with antigen. Moreover, the immunogenicity of DNA vaccine vectors expressing Ag85B and CD40L separately was comparable to that of vectors engineered to co-express Ag85B and CD40L. There may be economical and practical considerations for using co-expressed proteins in vector systems that influence future vaccine design and development.

The effects of CD40L on vaccine immunogenicity were more pronounced in prime-boost immunization strategies following Ad booster vaccinations. Prime-boosting has been shown to induce both quantitatively and qualitatively superior T cell responses to vaccine-encoded antigens compared to conventional or single vector-based immunization strategies [29-32]. Here, the inclusion of CD40L as a molecular adjuvant led to route-dependent enhancement of the vaccine-induced immune responses. Delivery of Ad vaccine vectors expressing Ag85B and CD40L via the intramuscular route preferentially increased the magnitude of circulating CD8+ T cell responses, but had little effect on CD4+ T cell responses. In contrast, the same Ad vaccine vectors delivered via the intranasal route selectively increased numbers of pulmonary mucosal and circulating CD4+ T cells, but had with little influence on CD8+ T cell numbers. The reason for this dichotomy is unclear. However, experimental evidence suggests that, following intranasal administration, exogenous CD40L induces pulmonary inflammation that is mediated by CD40+ bone marrow (BM)-derived cells, in particular alveolar macrophages, reinforced by CD40+ non-BM-derived cells, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells, and characterized by B and T cell infiltrates in the pulmonary tissues [41-43]. The introduction of a vaccine antigen into this pro-inflammatory microenvironment may at least partially explain the observed route-dependent differences in vaccine-induced immune responses. This phenomenon may have significant implications for the use of CD40L as an adjuvant to promote local pulmonary immune responses, particularly against respiratory pathogens.

We have previously shown that CD40L could enhance vaccine-induced immunity in murine models of CD4+ T cell deficiency [23-24]. We sought here to determine how CD40L influenced T cell responses under conditions of immunodeficiency, evaluating DNA/Ad prime boost immunizations strategies in both CD4-depleted and CD4-ablated animals. Our results showed that the development of CD8+ T cell responses was limited in CD4-ablated, but not CD4-depleted, animals. Furthermore, CD40L delivery via the intranasal route did not influence CD8+ T cell responses. It is possible that heterologous boosting with Ad vaccine vectors via the IM route simply enhanced the CD8+ T cell responses elicited by DNA priming, whereas events downstream of pulmonary mucosal immunization limited the induction of CD8+ T cell responses in the circulation. It is also conceivable that Ad vaccine vectors facilitate increased cross-presentation of vaccine antigen in the context of MHC class I molecules in the muscle, but not pulmonary mucosal, tissues to further enhance CD8+ T cell responses following IM delivery. While intranasal delivery of CD40L did not have a measurable influence on antigen-specific CD8+ T cell numbers, there is evidence that CD40L may also influence the longevity and functionality of memory CD8+ T cells [10, 11]. The potential long-term influence of CD40L is a topic of interest for future studies.

While it has been documented that functional CD8+ T cells may develop in the absence of CD4+ T cells [44], our findings suggest that CD4+ T cells are required for the development of robust CD8+ T cell responses. Not surprisingly, CD40L failed to induce robust CD4+ T cell responses in CD4-ablated animals. In fact, abrogation of the CD4+ T cell population in ablated animals precluded the detection of virtually any CD4+ T cells responsive to vaccine antigens. However, in CD4-depleted animals, in which circulating and lymphoid CD4+ T cell numbers were significantly reduced, vector-directed exogenous CD40L increased the magnitude of vaccine-induced CD4+ T cell responses in local mucosal tissues as well as in the circulation. Thus, exogenous CD40L retains potent adjuvant activity for Th1-type T cell responses, even under conditions of immunodeficiency.

In addition to enhancing the magnitude of vaccine-induced CD4+ T cell responses observed in the lung-associated lymph nodes, CD40L significantly influenced the generation of broad, polyfunctional Th1-type CD4+ T cell subsets. Polyfunctional, or multiple-cytokine-secreting, T cell subsets have been reported to mediate enhanced protective efficacy in a variety of disease models including HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis [31,32,45,46]. In immunocompetent animal models, immunization with Ag85B and CD40L elicited marked increases in the IFN-γ/TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cell subset, and more modest increases in the IFN-γ/IL-2/TNF-α-secreting subset. These polyfunctional T cell subsets have been associated, respectively, with effector and memory T cell activity in other disease models [31,32,45,46]. It is well-established that CD40L is critical for the initiation and generation of cellular immune responses through the provision of key co-stimulatory signals, licensing of APCs to activate T cells, and promoting cell survival and proliferation [2,3,9,10,47-51]. CD4-depleted animals immunized with Ag85B and CD40L lacked appreciable numbers of responsive CD4+ T cells of the IFN-γ/TNF-α phenotype, with only IL-2-secreting CD4+ T cell subsets present at appreciable levels, in particular the IFN-γ/IL-2/TNF-α-secreting CD4+ T cell population. The apparent “loss” of non-IL-2-secreting CD4+ T cell subsets in CD4-depleted animals, particularly the IFN-γ/TNF-α-secreting subset, may be more a consequence of periodic administration of CD4-depleting antibodies than a failure to induce these subsets in immunodeficient mice. The increased percentages of IL-2-secreting CD4+ T cell subsets observed in CD4-depleted animals given CD40L would also suggest a CD40L-mediated enhancement of cell survival or proliferation. Taken together, our results demonstrate that CD40L has the capacity to increase the magnitude and polyfunctionality of vaccine-induced immunity, particularly CD4+ T cell responses, in both normal and CD4+ T cell deficient hosts.

The level of CD4+ T cell deficiency achieved in our CD4-depleted animals represents a significant reduction in both the circulating and tissue-resident CD4+ T cell populations, with less than half the number of CD4+ T cells as age-matched controls. No outward signs of constitutional impairment were observed in these animals. However, the level of CD4+ T cell depletion seen in these mice was sufficient to limit both the magnitude of vaccine-induced immune responses compared to those induced in normal animals. Furthermore, immunization with Ag85B and CD40L was able to “overcome” reduced T cell numbers in CD4-depleted animals to restore, at least partially, the vaccine-induced responses observed in normal animals, particularly with respect to their magnitude and polyfunctionality. While CD40L cannot serve a surrogate for CD4+ T cells, here we have demonstrated that it has the capacity to overcome limitations imposed by CD4-depletion. Exogenous CD40L may represent a useful strategy to maintain or enhance T cell immunity in immunodeficient individuals who, nevertheless, retain some degree of immune function.

In this study, we used the mycobacterial protein Ag85B as our vaccine antigen. Ag85B and other members of the Ag85 complex have been widely used as potential vaccine antigens against pulmonary tuberculosis, mediating at least partial protection against tuberculosis in some studies [52-53]. Host immunity against tuberculosis is at least partially dependent on intact cellular immune responses, particularly CD4+ T cell responses, while CD4 T cell deficiency has a direct impact on the risk for developing active mycobacterial disease [53-54]. Here, we have shown that exogenous, vector-directed CD40L can enhance vaccine-induced immune responses to Ag85B in both normal and CD4+ T cell deficient hosts. Experiments are underway to test the protective efficacy of CD40L-adjuvanted vaccines in murine models of pulmonary M. tuberculosis infection, in both normal and CD4-deficient animals.

Highlights.

Vector-expressed CD40L functions as a vaccine adjuvant for circulating and lung mucosal T cell responses.

CD40L adjuvant activity in booster immunizations is route-dependent.

CD40L adjuvant activity enhances the magnitude of vaccine-induced polyfunctional T cell responses

CD40L cannot restore vaccine-induced immunity in a CD4-ablated mouse model.

CD40L enhances vaccine-induced immunity in a CD4-depleted mouse model.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH Grants 5RO1AI58810, 3R01AI058810-06S2 and P01HL076100 (AJR). We would also like to thank Constance Porretta (Analytical Cytology Core Laboratory / Flow Cytometry Facility, LSUHSC-NO) for her technical assistance with flow cytometry experiments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duchini A, Goss JA, Karpen S, Pockros PJ. Vaccinations for adult solid-organ transplant recipients: current recommendations and protocols. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003;16:357–64. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.3.357-364.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grewal IS, Flavell RA. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:111–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40-CD40 ligand. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67(1):2–17. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clarke SR. The critical role of CD40/CD40L in the CD4-dependent generation of CD8+ T cell immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67(5):607–14. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts TH. TNF/TNFR family members in costimulation of T cell responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:23–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quezada SA, Jarvinen LZ, Lind EF, Noelle RJ. CD40/CD154 interactions at the interface of tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:307–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugamura K, Ishii N, Weinberg AD. Therapeutic targeting of the effector T-cell co-stimulatory molecule OX40. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(6):420–31. doi: 10.1038/nri1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellino F, Germain RN. Cooperation between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells: when, where, and how. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:519–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop GA, Hostager BS. The CD40-CD154 interaction in B cell-T cell liaisons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14(3-4):297–309. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borrow P, Tough DF, Eto D, Tishon A, Grewal IS, Sprent J, Flavell RA, Oldstone MB. CD40 ligand-mediated interactions are involved in the generation of memory CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) but are not required for the maintenance of CTL memory following virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72(9):7440–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7440-7449.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachmann MF, Schwarz K, Wolint P, Meijerink E, Martin S, Manolova V, Oxenius A. Cutting edge: distinct roles for T help and CD40/CD40 ligand in regulating differentiation of proliferation-competent memory CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(4):2217–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez MG, Shen L, Rock KL. CD40-CD40 ligand interaction between dendritic cells and CD8+ T cells is needed to stimulate maximal T cell responses in the absence of CD4+ T cell help. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2844–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin F, Peng Y, Jones LA, Verardi PH, Yilma TD. Incorporation of CD40 Ligand into the envelope of pseudotyped single-cycle simian immunodeficiency viruses enhances immunogenicity. J Virol. 2009;83:1216–27. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01870-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manoj S, Griebel PJ, Babiuk LA, van Drunen Littel-van den Hur S. Modulation of immune responses to bovine herpesvirus-1 in cattle by immunization with a DNA vaccine encoding glycoprotein D as a fusion protein with bovine CD154. Immunol. 2004;112(2):328–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01877.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sin JI, Kim JJ, Zhang D, Weiner DB. Modulation of cellular responses by plasmid CD40L:CD40L plasmid vectors enhance antigen-specific helper T cell type 1 CD4+ T cell-mediated protective immunity against herpes simplex virus type 2 in vivo. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12(9):1091–102. doi: 10.1089/104303401750214302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tripp RA, Jones L, Anderson LJ, MBrown MP. CD40 ligand (CD154) enhances the Th1 and antibody responses to respiratory syncytial virus in the BALB/c mouse. J Immunol. 2000;164:5913–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gómez CE, Nájera JL, Sánchez R, Jiménez V, Esteban M. Multimeric soluble CD40 ligand (sCD40L) efficiently enhances HIV specific cellular immune responses during DNA prime and boost with attenuated poxvirus vectors MVA and NYVAC expressing HIV antigens. Vaccine. 2009;27:3165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao Q, Fischer KP, Li L, Agrawal B, Berhane Y, Tyrrell DL, Gutfreunda KS, Pasick J. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a DNA vaccine encoding a chimeric protein of avian influenza hemagglutinin subtype H5 fused to CD154 (CD40L) in Peking ducks. Vaccine. 2010;28:8147–56. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao J, Wang X, Du Y, Li Y, Wang X, Jiang P. CD40 ligand expressed in adenovirus can improve the immunogenicity of the GP3 and GP5 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus in swine. Vaccine. 2010;28:7514–22. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang YC, Thoman M, Linton PJ, Deisseroth A. Use of CD40L immunoconjugates to overcome the defective immune response to vaccines for infections and cancer in the aged. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:1949–57. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0718-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dullforce P, Sutton DC, Heath AW. Enhancement of T-cell independent immune responses in vivo by CD40 antibodies. Nat Med. 1998;4:88–91. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malaspina A, Moir S, Orsega SM, Vasquez J, Miller NJ, Donoghue ET, Kottilil S, Gezmu M, Follmann D, Vodeiko GM, Levandowski RA, Mican JM, Fauci AS. Compromised B cell responses to influenza vaccination in HIV-infected individuals. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1442–50. doi: 10.1086/429298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng M, Shellito JE, Marrero L, Zhong Q, Julian S, Ye P, Wallace V, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls JK. CD4+ T cell-independent vaccination against Pneumocystis carinii in mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;108(10):1469–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI13826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng M, Ramsay AJ, Robichaux MB, Norris KA, Kliment C, Crowe C, Rapaka RR, Steele C, McAllister F, Shellito JE, Marrero L, Schwarzenberger P, Zhong Q, Kolls JK. CD4+ T cell-independent DNA vaccination against opportunistic infections. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3536–44. doi: 10.1172/JCI26306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Belisle JT, Vissa VD, Sievert T, Takayama K, Brennan PJ, Besra GS. Role of the major antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cell wall biogenesis. Science. 1997;276(5317):1420–2. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boesen H, Jensen BN, Wicke T, Anderson P. Human T-cell responses to secreted antigen fractions of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1995;63(4):1491–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1491-1497.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mehra V, Gong JH, Iyer D, Lin Y, Boylen CT, Bloom BR, Barnes PF. Immune response to recombinant mycobacterial proteins in patients with tuberculosis infection and disease. J Infect Dis. 1996;174(2):431–4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper AM, Callahan JE, Frank AA, Orme IM. Expression of memory immunity in the lung following re-exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Estcourt MJ, Ramsay AJ, Brooks A, Thomson SA, Medveckzy CJ, Ramshaw IA. Prime-boost immunization generates a high frequency, high-avidity CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocyte population. Int Immunol. 2002;14(1):31–7. doi: 10.1093/intimm/14.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramshaw IA, Ramsay AJ. The prime-boost strategy:exciting prospects for improved vaccination. Immunol Today. 2000;21(4):163–5. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01612-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darrah PA, Patel DT, De Luca PM, Lindsay RW, Davey DF, Flynn BJ, Hoff ST, Anderson P, Reed SG, Morris SL, Roederer M, Seder RA. Multifunctional TH1 cells define a correlate of vaccine-mediated protection against Leishmania major. Nat Med. 2007;13(7):843–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kannanganat S, Ibegbu C, Chennareddi L, Robinson HL, Amara RR. Multiple-cytokine-producing antiviral CD4 T cells are functionally superior to single-cytokine-producing cells. J Virol. 1996;81(16):8468–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00228-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelsall BL, Stuber E, Neurath M, Strober W. Interleukin-12 production by dendritic cells. The role of CD40-CD40L interactions in Th1 T-cell responses. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;795:116–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb52660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shellito J, Suzara VV, Blumenfeld W, Beck JM, Steger JH, Ermak TH. A new model of Pneumocystis carinii infection in mice selectively depleted of helper T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 1990;85(5):1686–93. doi: 10.1172/JCI114621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kolls JK, Habetz S, Shean MK, Vazquez C, Brown JA, Lei D, Schwarzenberger P, Ye P, Nelson S, Summer WR, Shellito JE. IFN-gamma and CD8+ T cells restore host defenses against Pneumocystis carinii in mice depleted of CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162(5):2890–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Izzo AA, North RJ. Evidence for an alpha/beta T cell-independent mechanism of resistance to mycobacteria. Bacillus-Calmette-Guerin causes progressive infection in severe combined immunodeficient mice, but not in nude mice or in mice depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176(2):581–6. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.2.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shedlock DJ, Weiner DB. DNA vaccination:antigen presentation and the induction of immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;68(6):793–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barouch DH, Letvin NL, Seder RA. The role of cytokine DNAs as vaccine adjuvants for optimizing cellular immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:266–74. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sumida SM, McKay PF, Truitt DM, Kishko MG, Arthur JC, Seaman MS, Jackson SS, Gorgone DA, Lifton MA, Letvin NL, Barouch DH. Recruitment and expansion of dendritic cells in vivo potentiate the immunogenicity of plasmid DNA vaccines. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(9):1334–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI22608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hollenbaugh D, Grosmaire LS, Kullas CD, Chalupny NJ, Braesch-Anderson S, Noelle RJ, Stamenkovic I, Ledbetter JA, Aruffo A. The human T cell antigen gp39, a member of the TNF gene family, is a ligand for the CD40 receptor:expression of a soluble form of gp39 with B cell co-stimulatory activity. EMBO J. 1992;11(12):4313–21. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiley JA, Harmsen AG. CD40 ligand is required for resolution of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in mice. J Immunol. 1995;155(7):3525–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wiley JA, Geha R, Harmsen AG. Exogenous CD40 ligand induces a pulmonary inflammation response. J Immunol. 1997;158(6):2932–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wiley JA, Harmsen AG. Bone marrow-derived cells are required for the induction of a pulmonary inflammatory response mediated by CD40 ligation. Am J Pathol. 2008;154(3):919–26. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65339-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seder RA, Darrah PA, Roederer M. T-cell quality in memory and protection:implications for vaccine design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(4):247–58. doi: 10.1038/nri2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marzo AL, Vezys V, Klonowski KD, Lee SJ, Muralimohan G, Moore M, Tough DF. Lefrancois L Fully functional memory CD8 T cells in the absence of CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(2):969–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scriba TJ, Tameris M, Mansoor N, Smit E, van der Merwe L, Fatima I, Keyser A, Moyo S, Brittain N, Lawrie A, Gelderbloem S, Veldsman A, Hatherill M, Hawkridge A, Hill AVS, Hussey GD, Mahomed H, McShane H, Hanekom WA. Modified vaccinia Ankara-expressing Ag85A, a novel tuberculosis vaccine, is safe in adolescents and children, and induces polyfunctional CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(1):279–90. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stuber E, Strober W, Neurath M. Blocking the CD40L-CD40 interaction in vivo specifically prevents the priming of T helper 1 cells through the inhibition of interleukin 12 secretion. J Exp Med. 1996;183(2):693–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clarke SR. The critical role of CD40/CD40L in the CD4-dependent generation of CD8+ T cell immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67(5):607–14. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Castellino F, Germain RN. Cooperation between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells:when, where, and how. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:519–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacLeod M, Kwakkenbos MJ, Crawford A, Brwon S, Stockinger B, Schepers K, Schumacher T, Gray D. CD4 memory T cells survive and proliferate but fail to differentiate in the absence of CD40. J Exp Med. 2006;203(4):897–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray PJ. Defining the requirements for immunological control of mycobacterial infections. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7(9):366–72. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01567-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McShane H. Developing an improved vaccine against tuberculosis. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3(3):299–306. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baumann S, Nasser Eddine A, Kaufmann S. Progress in tuberculosis vaccine development. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18(4):438–48. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goter-Robinson C, Derrick SC, Yang AL, Jeon BY, Morris SL. Protection against an aerogenic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in BCG-immunized and DNA-vaccinated mice is associated with early type I cytokine responses. Vaccine. 2006;24(17):3522–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]