Abstract

Background

The incremental value of CAC over traditional risk factors to predict coronary vasodilator dysfunction and inherent myocardial blood flow (MBF) impairment is only scarcely documented (MBF). The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the relationship between CAC content, hyperemic MBF, and coronary flow reserve (CFR) in patients undergoing hybrid 15O-water PET/CT imaging.

Methods

We evaluated 173 (mean age 56 ± 10, 78 men) patients with a low to intermediate likelihood for coronary artery disease (CAD), without a documented history of CAD, undergoing vasodilator stress 15O-water PET/CT and CAC scoring. Obstructive coronary artery disease was excluded by means of invasive (n = 44) or CT-based coronary angiography (n = 129).

Results

91 of 173 patients (52%) had a CAC score of zero. Of those with CAC, the CAC score was 0.1-99.9, 100-399.9, and ≥400 in 31%, 12%, and 5% of patients, respectively. Global CAC score showed significant inverse correlation with hyperemic MBF (r = −0.32, P < .001). With increasing CAC score, there was a decline in hyperemic MBF on a per-patient basis [3.70, 3.30, 2.68, and 2.53 mL · min−1 · g−1, with total CAC score of 0, 0.1-99.9, 100-399.9, and ≥400, respectively (P < .001)]. CFR showed a stepwise decline with increasing levels of CAC (3.70, 3.32, 2.94, and 2.93, P < .05). Multivariate analysis, including age, BMI, and CAD risk factors, revealed that only age, male gender, BMI, and hypercholesterolemia were associated with reduced stress perfusion. Furthermore, only diabetes and age were independently associated with CFR.

Conclusion

In patients without significant obstructive CAD, a greater CAC burden is associated with a decreased hyperemic MBF and CFR. However, this association disappeared after adjustment for traditional CAD risk factors. These results suggest that CAC does not add incremental value regarding hyperemic MBF and CFR over established CAD risk factors in patients without obstructive CAD.

Keywords: Coronary artery calcium, hyperemic myocardial blood flow, coronary risk factors

Introduction

The presence of coronary artery calcium (CAC) is a marker of vascular injury and related to the extent of coronary atherosclerotic burden.1-3 Computed tomography (CT) is a routinely used and a well-validated non-invasive imaging modality for the assessment and quantification of coronary atherosclerosis as represented by CAC.3 Previous studies have shown a positive relation between CAC and the anatomic severity of coronary artery disease (CAD),2,4,5 even after correction for traditional risk factors.6-8 These risk factors in turn are known to affect myocardial perfusion, even in the absence of CAD.9 The incremental value of CAC over traditional risk factors to predict coronary vasodilator dysfunction and inherent myocardial blood flow (MBF) impairment is only scarcely documented.10-14 Moreover, the results from these studies are conflicting and hampered by small sample size, varying patients populations, and the use of suboptimal imaging techniques to quantify MBF.

This study aimed to determine the relationship between CAC score and MBF in a large clinical cohort of symptomatic subjects suspected of and with risk factors for CAD undergoing hybrid 15O-water PET/CT imaging, in whom obstructive CAD was excluded by means of invasive (ICA) or CT-based coronary angiography (CTCA). In addition, the additive impact of CAC score on MBF over gender, age, and conventional CAD risk factors was explored.

Methods

Patient Population

Data were obtained from a cohort of 249 patients being clinically evaluated for CAD and therefore referred for CTCA, CAC-scoring, and PET MBF measurements on a hybrid PET/CT scanner (Gemini TF 64, Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Patients were referred because of stable (atypical) angina or an elevated risk for CAD (presence of two or more risk factors) in the absence of symptoms. Hypertension was defined as a blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or the use of anti-hypertensive medication. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total cholesterol level ≥5 mmol/L or treatment with cholesterol lowering medication. Patients were classified as having diabetes if they were receiving treatment with oral hypoglycemic drugs or insulin. A positive family history of CAD was defined by the presence of CAD in first-degree relatives younger than 55 years in men or 65 years in women. Obstructive CAD was considered to have been ruled out when either one of the following criteria had been met: (1) absence of a luminal stenosis of more than 50% at ICA (N.B. Referral for ICA was left to the discretion of the treating physician); (2) when ICA was not available, a CTCA of sufficient quality enabling adequate grading of all major coronary segments which did not display a stenosis of more than 50%. Exclusion criteria were atrial fibrillation, second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, symptomatic asthma, pregnancy, or a documented history of CAD. A history of CAD was defined as a prior percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, or a previous myocardial infarction. A total of 173 out of the 249 evaluated patients met these criteria and are described in the current study (78 men: mean age 55, range 33-79 years; and 95 women: mean age 57, range 31-84 years). Electrocardiography did not show signs of a previous myocardial infarction, and echocardiography showed a normal left ventricular function without wall motion abnormalities in all patients. CAD pre-test likelihood was determined according to the Diamond and Forrester criteria,15 using percent cutoffs of <13.4%, >87.2%, and in between for low, high, and intermediate pre-test likelihood, respectively.

PET Imaging

Patients were instructed to refrain from intake of products containing caffeine or xanthine 24 hours prior to the scan. After a scout CT for patient positioning and 2 minutes after the start of intravenous adenosine infusion 140 μg · kg−1 · min−1, 370 MBq of 15O-water was injected as a 5 mL (0.8 mL · s−1) bolus, followed immediately by a 35-mL saline flush (2 mL · s−1). A 6-minute emission scan was started simultaneously with the administration of 15O-water. This dynamic scan sequence was followed immediately by a respiration-averaged low dose CT scan (LD-CT) to correct for attenuation (55 mAs; rotation time, 1.5 s; pitch, 0.825; collimation, 16 × 0.625; acquiring 20 cm in 37 s) during normal breathing.16 Adenosine infusion was terminated after the LD-CT. After an interval of 10 minutes to allow for decay of radioactivity and washout of adenosine, an identical PET sequence was performed during resting conditions. Images were reconstructed using the 3D row action maximum likelihood algorithm into 22 frames (1 × 10, 8 × 5, 4 × 10, 2 × 15, 3 × 20, 2 × 30, and 2 × 60 seconds), applying all appropriate corrections. Parametric MBF images were generated and quantitative analysis was performed using in-house developed software, Cardiac VUer.17,18 MBF was expressed in mL · min−1 · g−1 of perfusable tissue and analyzed according to the 17-segment model of the American Heart Association.19 In addition to calculating the MBF for the left ventricle as a whole, MBF was calculated for each of three vascular territories (LAD, left anterior descending; LCx, left circumflex; and RCA, right coronary artery).

CT Imaging

Patients with a stable heart rate below 65 bpm (either spontaneous or after administration of oral and/or intravenous metoprolol) underwent a CT scan for calcium scoring and/or CTCA. A standard scanning protocol was applied, with 64 × 0.625-mm section collimation, 420-ms gantry rotation time, 120-kV tube voltage, and a tube current of 800 to 1000 mA (for CTCA), and 100 to 120 mA (for calcium scoring) depending on patients body size. All scans were performed with electrocardiogram-gated dose modulation to decrease the radiation dose. Calcium scoring was obtained during a single breath hold and coronary calcification was defined as a plaque with an area of 1.03 mm2 and a density ≥130 HU. The CAC score was calculated according to the method described by Agatston.20 After calcium scoring a CTCA was performed, whereby a bolus of 100-mL iodinated contrast agent was injected intravenously (5 mL · s−1) followed by a 50 mL NaCl 0.9% flush. All CT-scans were analyzed with a 3-dimensional workstation (Brilliance, Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) by an experienced radiologist and cardiologist who were blinded to the PET-results. The coronary tree was evaluated according to a 16-segment coronary artery model modified from the American Heart Association.21

Invasive Coronary Angiography

ICA was performed according to standard clinical protocols. The coronary tree was divided to a 16-segment coronary artery model modified from the American Heart Association.21 Significant CAD was ruled out when no stenosis was present or the diameter stenosis was visually scored ≤50%. All images were interpreted by at least two experienced interventional cardiologists.

Data Interpretation

CAC scores were calculated separately for the LAD (including the left main coronary artery), LCX artery, and RCA and then summed to provide a total CAC score. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) was defined as the ratio between hyperemic and baseline MBF. Coronary vascular resistance (mm Hg · mL · min−1 · g−1) during hyperemia was calculated by dividing mean arterial pressure (MAP) by hyperemic MBF.22 Furthermore, to study heterogeneity in MBF, the coefficient of variation (COV) was calculated on a per patient basis as the ratio of the standard deviation of the 17 myocardial segments and mean hyperemic MBF for that patient. Finally, to explore a potential perfusion decline along the course of the coronary artery from proximal to distal segments, the longitudinal perfusion gradient was calculated according to the method previously described by Hernandez-Pampaloni et al23 and initially proposed by Gould et al.24

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean values ± SD, whereas categorical variables are expressed as actual numbers. For most analyses, we categorized CAC into 4 groups (0, 0.01-99.9, 100-399.9, and ≥400) to accommodate the fact that 52 % of the studied subjects had a CAC score of 0. The ln (CAC score + 1) transformation better normalized CAC distribution. Continuous variables between males and females were compared using the paired or unpaired two-sided Student’s t test, as appropriate. Comparison of differences in perfusion parameters across increasing levels of CAC score were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s correction for multiple pair-wise comparisons for localizing the source of the difference. Evaluation of relationships between variables was performed using Spearman’s rank correlation analysis. Univariable linear regression analyses were performed to examine the relationship between cardiac risk factors, age, gender, ln(CAC + 1) score and change in hyperemic MBF and CFR. In addition, predictors associated with hyperemic MBF and CFR, based on evidence from the literature,9 were included simultaneously in a multiple linear regression model using backward elimination. A P value ≤.05 (two-sided) was considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software package (SPSS 15.0, Chicago, IL).

Results

Significant CAD was considered to be ruled out by ICA (44) and CTCA (129) in all patients (n = 173). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The 173 subjects included had a global baseline MBF of 1.05 ± 0.34 mL · min−1 · g−1. During adenosine-induced hyperemia, MBF increased significantly to 3.40 ± 1.19 mL · min−1 · g−1 (P < .001). Coronary flow reserve (CFR) averaged 3.45 ± 1.32. The median CAC score in this cohort of symptomatic patients was 0 (interquartile range 0-31). Ninety-one of hundred and seventy-three patients (52%) had a CAC score of zero. Of those with CAC, the CAC score was 0.1-99.9, 100-399.9, and ≥ or =400 in 31%, 12%, and 5% of patients, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 173)

| Characteristics | N (%) or mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 56 ± 10 |

| Male gender | 78 (45%) |

| BMI (kg · m−2) | 27 ± 4 |

| Diabetes | 36 (21%) |

| Hypertension | 75 (43%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 53 (31%) |

| Smoking history | 69 (40%) |

| Family history | 84 (49%) |

| Reason for referral | |

| Typical angina pectoris | 36 (21%) |

| Atypical angina pectoris | 59 (34%) |

| Non-anginal chest pain | 57 (33%) |

| High risk, no chest discomfort | 21 (12%) |

| Pre-test likelihood of CAD | 0.37 ± 0.30 |

CAD, Coronary artery disease; BMI, body mass index.

Hemodynamics

Table 2 summarizes the hemodynamic characteristics. During adenosine-induced hyperemia, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and rate-pressure product increased significantly compared to baseline, whereas no significant changes occurred in diastolic blood pressure.

Table 2.

Systemic hemodynamics at baseline and hyperemia

| Parameter | Mean value ± SD |

|---|---|

| Heart rate (bpm) | |

| Baseline | 62 ± 10 |

| Hyperemia | 81 ± 13* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |

| Baseline | 113 ± 19 |

| Hyperemia | 115 ± 19* |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |

| Baseline | 60 ± 9 |

| Hyperemia | 60 ± 9 |

| Mean arterial pressure (mm Hg) | |

| Baseline | 78 ± 11 |

| Hyperemia | 78 ± 12 |

| Rate-pressure product | |

| Baseline | 7064 ± 2019 |

| Hyperemia | 9445 ± 2407* |

Bpm, Beats per minute.

* P < .05 vs baseline.

Per Patient Analysis

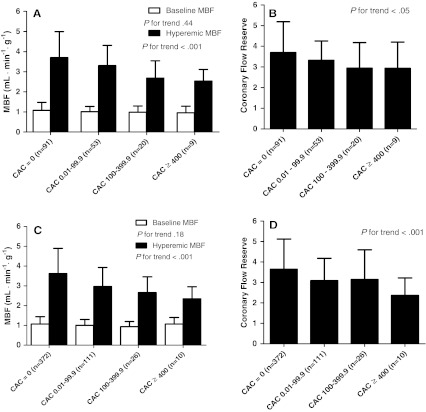

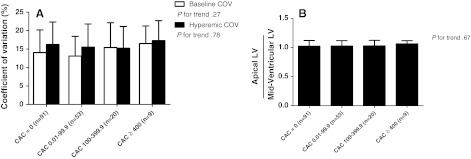

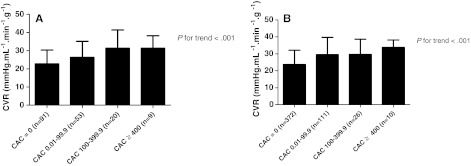

Stratification of patients into four groups based on their CAC scores (0, 0.01-99.9, 100-399.9, and ≥400) resulted in a comparable global baseline MBF among the four CAC groups, whereas hyperemic MBF (3.70, 3.30, 2.68, and 2.53 mL · min−1 · g−1) and CFR (3.70, 3.32, 2.94, and 2.93) gradually decreased with increasing CAC levels (Figure 1A, B). The COV, as a marker of heterogeneity in MBF, was comparable across all CAC score groups during both resting (P = .27) and stress conditions (P = .78) (Figure 2A). Furthermore, comparison of hyperemic MBF in the base-to-apex direction demonstrated no longitudinal perfusion gradient with increasing CAC scores (P = .67, Figure 2B). Minimal coronary vascular resistance (CVR) displayed a significant stepwise increase (P < .001) with increasing total CAC score (Figure 3A). Spearman’s rank correlations of baseline MBF, hyperemic MBF, CFR, minimal CVR, and COV of hyperemic MBF with ln (CAC + 1) score were −0.08 (P = .27), −0.32 (P< .001), −0.21 (P < .01), 0.33 (P < .001), and −0.05 (P = .54), respectively.

Figure 1.

Per-patient (A, B) and per-vessel analysis (C, D). Relationships between coronary artery calcium (CAC) and A, C myocardial blood flow (MBF), and B, D coronary flow reserve (CFR)

Figure 2.

Relationships between coronary artery calcium (CAC) and A coefficient of variation (COV), and B longitudinal perfusion gradient (mid-ventricular to apical regions)

Figure 3.

Per-patient analysis (A) and per-vessel analysis (B). Relationships between coronary artery calcium (CAC) and hyperemic coronary vascular resistance (CVR)

Per Vessel Analysis

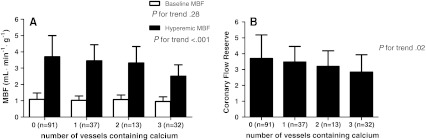

In 173 patients, a total of 519 vascular territories were analyzed. The correlation between per-vessel ln (CAC + 1), hyperemic MBF (r = −0.31, P < .001), CFR (r = −0.22, P < .001), and minimal CVR (r = 0.33, P < .001) was modest but statistically significant. Furthermore, when grouped according to per-vessel CAC score, baseline MBF was comparable across increasing levels of CAC score (P = .18). In addition, mean hyperemic MBF (3.62, 2.97, 2.66, and 2.35 mL · min−1 · g−1), CFR (3.65, 3.09, 3.15, and 2.36) progressively declined across increasing CAC levels (P < .001) (Figure 1C, D). Minimal CVR showed a stepwise increase across increasing per-vessel CAC levels (24, 30, 30, and 34 mm Hg · mL · min−1 · g−1, respectively, P < .001) (Figure 3B). In addition, hyperemic MBF and CFR decreased with increasing number of coronary vessels containing atherosclerosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relationship between number of vessels containing CAC and myocardial blood flow (MBF) (A), and B coronary flow reserve

Predictors of Hyperemic MBF and CFR

Univariable regression analyses demonstrated that age (P < .01), male gender (P < .001), BMI (P < .01), diabetes (P = .04), hypercholesterolemia (P = .04), and ln(CAC + 1) score (P < .001) displayed an inverse relationship with hyperemic MBF. Furthermore, multivariable linear regression analyses were performed with predictors which were selected based on evidence from the literature on their association with an impaired hyperemic MBF or CFR.9 When these predictors, including ln(CAC + 1) score, were put simultaneously into a multivariable regression model only age, male gender, BMI, and hypercholesterolemia were identified to have an independently negative impact on hyperemic MBF (Table 3a). In addition, univariable and multivariable regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of CFR. Univariable analyses showed that age (P < .01), BMI (P = .03), diabetes (P < .01), hypertension (P = .04), and total ln(CAC + 1) (P < .01) were associated with a negative impact on CFR. Multivariable regression analyses demonstrated that only age and diabetes were independently correlated with a diminished CFR (Table 3b).

Table 3.

Backward multiple linear regression analysis with hyperemic MBF (a) and CFR (b) as the dependent variables

| Independent variable | β | P value |

|---|---|---|

| (a) | ||

| Age | −0.03 | <.001 |

| Male gender | −1.07 | <.001 |

| BMI | −0.07 | <.001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | −0.36 | .04 |

| (b) | ||

| Age | −0.03 | <.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus type II | −0.51 | .04 |

After forcing age, gender, BMI, diabetes type II, hypertension, smoking history, hypercholesterolemia, family history and ln(CAC + 1) into the model. Only variables that had a P ≤ 0.05 were considered in the final model. MBF, Myocardial blood flow; CFR, coronary flow reserve; BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

The current study was conducted to explore the quantitative relationship between CAC and coronary vasodilator response in patients who were being evaluated for CAD by hybrid 15O-water PET/CT. In symptomatic patients with multiple risk factors and non-obstructive CAD, CAC score does not add incremental information over age, gender, and traditional risk factors to predict impairment of hyperemic MBF and CFR. Of interest, CAC was also not related to hyperemic perfusion heterogeneity or the longitudinal perfusion gradient from base to apex.

In line with the majority of previous studies, resting MBF was not related to the extent of coronary calcification.10-13 This observation is not surprising as resting MBF is modulated in response to myocardial metabolic demand and remains preserved till the point of a subtotal coronary stenosis.25,26 Schindler et al,14 however, have documented an inverse relation between CAC and resting MBF in a cohort of diabetic patients. These results may be explained by alterations in the hormonal milieu and insulin levels which are known to affect resting MBF in the more advanced stages or diabetes with coronary injury.27

The negative correlation between the extent of coronary calcium and hyperemic MBF and flow reserve is in concordance with prior studies in asymptomatic controls, patients suspected of CAD, and diabetics.10,11,28 Only studies including small number of patients or employing qualitative flow measurements instead of absolute quantitative MBF measurements have not been able to reproduce the relation between vasodilator function and CAC.12,13 Multivariate analysis revealed that only age, male gender, BMI, and hypercholesterolemia were associated with reduced stress perfusion. Of interest, CAC score was not an independent predictor of a diminished hyperemic MBF. This is consistent with previous work showing that CAC score has little incremental value in predicting a diminished vasodilator response.10,11 In contrast to the current data, in these previous studies significant CAD was not excluded and could therefore have contributed to the observed independent (weak) relationship between CAC and impaired MBF. Thus, although CAC is a strong predictor for future cardiovascular events and reflects total coronary atherosclerotic burden, the current results implicate that CAC score in symptomatic patients with multiple risk factors and no obstructive epicardial CAD, does not add incremental information regarding MBF over age, gender, BMI, and established coronary risk factors.

Another aspect of this study was to investigate the relation between heterogeneity of hyperemic MBF and CAC as some of the aforementioned studies have indicated such an relation.12,14 It was therefore hypothesized that increased levels of calcium may induce heterogeneity between coronary perfusion territories, on the one hand, and a longitudinal perfusion gradient from base to apex, on the other hand. Gould et al24 initially introduced the latter concept, where patients with non-significant CAD displayed a gradual longitudinal decline in hyperemic MBF from base to apex as measured with 13N-ammonia PET. These results were later confirmed by Hernandez-Pampaloni et al23 in asymptomatic patients with an increased risk profile for CAD. Invasive measurements have indeed demonstrated that a gradual hyperemic perfusion pressure gradient exists along the course of mild atherosclerotic coronary arteries.29 In the current study, however, there was no relationship between heterogeneity of hyperemic MBF and CAC. Moreover, no perfusion gradient was detected between the mid and the apical sections of the left ventricle with increasing CAC scores during adenosine-induced hyperemia. Several factors may have contributed to these observations. First, there might be differences between study populations. In the current study, 52% of patients displayed no coronary calcium and the lack of longitudinal perfusion gradient may well be explained by the lack of coronary artery disease in these patients in contrast to the cohort of patients described by Gould et al.24 Second, there are some methodological differences between studies. Previously documented base to apex gradients have been investigated using 13N-ammonia PET almost a decade ago. The scanner used in the current study, however, is characterized by a higher spatial resolution and hence less affected by partial volume effects. Moreover, the modeling procedure of 15O-water incorporates an intrinsic correction for partial volume effects. As wall thickness progressive declines from base to apex, part of the observed longitudinal perfusion gradient may be caused by partial volume effects. Third, the perfusion gradient was measured over only a relatively short longitudinal distance of the left ventricle, i.e., from the mid-ventricular to the apical portion in concordance with Hernandez-Pampaloni et al.23 This approach was chosen to avoid potential inclusion of the outflow tract of the left ventricle in the perfusion estimates. Nevertheless, when the longitudinal gradient was measured from the basal to the apical portion, no myocardial perfusion gradient was demonstrated in the current population (data not shown). In addition, the limited number of patients in the group having a CAC score ≥ 400 could have introduced bias. Further studies in larger populations are warranted to assess the effect of CAC on MBF heterogeneity.

Study Limitations

Some limitations of our study that may affect the current findings must be acknowledged. Significant CAD was presumed to have been excluded by invasive or CT-based coronary angiography. The number of routinely performed invasive coronary angiographies in the current population was limited. Although CTCA is an excellent tool for ruling out significant CAD with a negative predictive value of 97% to 99%,30,31 some patients with hemodynamic significant CAD may have been included. Furthermore, the current data were obtained in predominantly symptomatic patients and therefore the results may not be extrapolated to, for example, asymptomatic subjects. Studies in asymptomatic subjects have displayed conflicting results and therefore larger studies are warranted to further investigate the relationship between CAC score and coronary vasodilator function in specific subpopulations. Finally, it must be emphasized that for subgroup analyses the studied patient population was too small to draw definite conclusions.

Conclusions

In patients with an intermediate pre-test likelihood of CAD and with multiple CAD risk factors there was a statistically significant inverse correlation between hyperemic MBF, CFR, and the extent of CAC. However, this association disappeared after adjusting for age, gender, BMI, and conventional risk factors. These results suggest that CAC score does not add incremental value regarding hyperemic MBF and CFR over established CAD risk factors in patients with an intermediate pre-test likelihood of CAD and no obstructive epicardial CAD. Therefore, coronary artery calcifications and vasodilator reactivity reflect different aspects of coronary atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judith van Es, Robin Hemminga, Amina Elouahmani and Nasserah Sais for performing the scans and Kevin Takkenkamp and Henri Greuter for producing 15O-labeled water.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Sangiorgi G, Rumberger JA, Severson A, et al. Arterial calcification and not lumen stenosis is highly correlated with atherosclerotic plaque burden in humans: A histologic study of 723 coronary artery segments using nondecalcifying methodology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:126–133. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rumberger JA, Schwartz RS, Simons DB, Sheedy PF, III, Edwards WD, Fitzpatrick LA. Relation of coronary calcium determined by electron beam computed tomography and lumen narrowing determined by autopsy. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:1169–1173. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wexler L, Brundage B, Crouse J, et al. Coronary artery calcification: pathophysiology, epidemiology, imaging methods, and clinical implications. A statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Writing Group. Circulation. 1996;94:1175–1192. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.5.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rumberger JA, Sheedy PF, Breen JF, Schwartz RS. Electron beam computed tomographic coronary calcium score cutpoints and severity of associated angiographic lumen stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1542–1548. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haberl R, Becker A, Leber A, et al. Correlation of coronary calcification and angiographically documented stenoses in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: Results of 1, 764 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:451–457. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho JS, Fitzgerald SJ, Stolfus LL, et al. Relation of a coronary artery calcium score higher than 400 to coronary stenoses detected using multidetector computed tomography and to traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1444–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schmermund A, Denktas AE, Rumberger JA, et al. Independent and incremental value of coronary artery calcium for predicting the extent of angiographic coronary artery disease: Comparison with cardiac risk factors and radionuclide perfusion imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:777–786. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00265-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerci AD, Spadaro LA, Goodman KJ, et al. Comparison of electron beam computed tomography scanning and conventional risk factor assessment for the prediction of angiographic coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:673–679. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(98)00299-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaufmann PA, Camici PG. Myocardial blood flow measurement by PET: Technical aspects and clinical applications. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curillova Z, Yaman BF, Dorbala S, et al. Quantitative relationship between coronary calcium content and coronary flow reserve as assessed by integrated PET/CT imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1603–1610. doi: 10.1007/s00259-009-1121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L, Jerosch-Herold M, Jacobs DR, Jr, Shahar E, Detrano R, Folsom AR. Coronary artery calcification and myocardial perfusion in asymptomatic adults: The MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:1018–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wieneke H, Schmermund A, Ge J, et al. Increased heterogeneity of coronary perfusion in patients with early coronary atherosclerosis. Am Heart J. 2001;142:691–697. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.116764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirich C, Leber A, Knez A, et al. Relation of coronary vasoreactivity and coronary calcification in asymptomatic subjects with a family history of premature coronary artery disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:663–670. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1426-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schindler TH, Facta AD, Prior JO, et al. Structural alterations of the coronary arterial wall are associated with myocardial flow heterogeneity in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:219–229. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0885-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond GA, Forrester JS. Analysis of probability as an aid in the clinical diagnosis of coronary-artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197906143002402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lubberink M, Harms HJ, Halbmeijer R, de Haan S, Knaapen P, Lammertsma AA. Low-dose quantitative myocardial blood flow imaging using 15O-water and PET without attenuation correction. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:575–580. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.070748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harms HJ, Knaapen P, Raijmakers PG, Lammertsma AA, Lubberink M. Cardiac Vuer: Software for semi-automatic generation of parametric myocardial blood flow images from a [15O]H2O PET-CT scan. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:477. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.069716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harms HJ, Knaapen P, de Haan S, Halbmeijer R, Lammertsma AA, Lubberink M. Automatic generation of absolute myocardial blood flow images using [(15)O]H (2)O and a clinical PET/CT scanner. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:930–939. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1730-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: A statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2002;105:539–542. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975;51:5–40. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.51.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knaapen P, Camici PG, Marques KM, et al. Coronary microvascular resistance: Methods for its quantification in humans. Basic Res Cardiol. 2009;104:485–498. doi: 10.1007/s00395-009-0037-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Keng FY, Kudo T, Sayre JS, Schelbert HR. Abnormal longitudinal, base-to-apex myocardial perfusion gradient by quantitative blood flow measurements in patients with coronary risk factors. Circulation. 2001;104:527–532. doi: 10.1161/hc3001.093503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gould KL, Nakagawa Y, Nakagawa K, et al. Frequency and clinical implications of fluid dynamically significant diffuse coronary artery disease manifest as graded, longitudinal, base-to-apex myocardial perfusion abnormalities by noninvasive positron emission tomography. Circulation. 2000;101:1931–1939. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.16.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Carli M, Czernin J, Hoh CK, et al. Relation among stenosis severity, myocardial blood flow, and flow reserve in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1995;91:1944–1951. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.91.7.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uren NG, Melin JA, De Bruyne B, Wijns W, Baudhuin T, Camici PG. Relation between myocardial blood flow and the severity of coronary-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1782–1788. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406233302503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundell J, Knuuti J. Insulin and myocardial blood flow. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:312–319. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schindler TH, Schelbert HR, Quercioli A, Dilsizian V. Cardiac PET imaging for the detection and monitoring of coronary artery disease and microvascular health. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:623–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Bruyne B, Hersbach F, Pijls NH, et al. Abnormal epicardial coronary resistance in patients with diffuse atherosclerosis but “Normal” coronary angiography. Circulation. 2001;104:2401–2406. doi: 10.1161/hc4501.099316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henneman MM, Schuijf JD, van Werkhoven JM, et al. Multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography for ruling out suspected coronary artery disease: What is the prevalence of a normal study in a general clinical population? Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2006–2013. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kajander S, Joutsiniemi E, Saraste M, et al. Cardiac positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging accurately detects anatomically and functionally significant coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122:603–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.915009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]