Abstract

Statins, the widely prescribed cholesterol-lowering drugs for the treatment of cardiovascular disease, cause adverse skeletal muscle side effects ranging from fatigue to fatal rhabdomyolysis. The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of simvastatin on mitochondrial respiration, oxidative stress, and cell death in differentiated primary human skeletal muscle cells (i.e. myotubes). Simvastatin induced a dose dependent decrease in viability of proliferating and differentiating primary human muscle precursor cells, and a similar dose-dependent effect was noted in differentiated myoblasts and myotubes. Additionally, there were decreases in myotube number and size following 48 h of simvastatin treatment (5 µM). In permeabilized myotubes, maximal ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption, supported by palmitoyl-carnitine + malate (PCM, complex I and II substrates) and glutamate + malate (GM, complex I substrates), was 32–37% lower (P<0.05) in simvastatin treated (5 µM) vs. control myotubes, providing evidence of impaired respiration at complex I. Mitochondrial superoxide and hydrogen peroxide generation were significantly greater in the simvastatin treated human skeletal myotube cultures compared to control. In addition, simvastatin markedly increased protein levels of Bax (pro-apoptotic, +53%) and Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic, +100%, P<0.05), mitochondrial PTP opening (+44%, P<0.05), and TUNEL-positive nuclei in human skeletal myotubes, demonstrating up-regulation of mitochondrial-mediated myonuclear apoptotic mechanisms. These data demonstrate that simvastatin induces myotube atrophy and cell loss associated with impaired ADP-stimulated maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity, mitochondrial oxidative stress, and apoptosis in primary human skeletal myotubes, suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction may underlie human statin-induced myopathy.

Keywords: simvastatin, mitochondrial respiration, superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, oxidative stress, apoptosis, mitochondria, human skeletal muscle

INTRODUCTION

Statins are competitive inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in de novo cholesterol biosynthesis through the mevalonate synthesis pathway. Statins are the primary therapy for treating dyslipidemia and preventing cardiovascular disease (CVD). The therapeutic effects of statins for managing cholesterol, including the primary outcome of reduced atherogenesis, are well established. Additionally, statins have a number of pleiotropic, cholesterol-independent effects related to endothelial function[1], insulin sensitivity[2], and inflammation/immunomodulation[1]. In general, statins are well-tolerated; however, some statins, particularly lipophilic statins (e.g., simvastatin, atorvastatin, lovastatin, cerivastatin), are known to induce skeletal muscle toxicity. In fact, an estimated 5–10% of patients discontinue statin use due to myopathic symptoms ranging from mild to moderate muscle weakness, fatigue, and pain to life-threatening rhabdomyolysis[3, 4]. Reports of myositis and myopathic symptoms increase with increased statin dose[5], with different classes of statins, when statins are coupled with other drugs[6], and with exercise[7, 8]. The incidence of statin myopathy will likely increase due to recent guidelines which recommend lower target levels for low density lipoprotein (LDL) and thus more aggressive statin regimens[9, 10]. Additionally, based on the recently identified pleiotropic effects of statins, the incidence of reported and non-reported cases of statin myopathy is expected to rise with increased usage.

The mechanistic underpinnings of statin myopathy are likely multifactorial and partially attributed to the regulatory effects of statins on apoptosis [11–13] and proliferation[14–17]. How statins promote apoptosis and inhibit proliferation is fairly obscure; however, mitochondrial dysfunction may be central to these effects[18–21]. For example, within eight weeks of starting simvastatin (80 mg/d), patients display a decrease in mitochondrial citrate synthase enzyme and respiratory chain activities[19]. Statins also block the synthesis of ubiquinone (a.k.a., coenzyme Q10), a major electron carrier in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, leading to early speculation that statin-induced ubiquinone deficiency could participate in statin-associated myopathy [22–24]. However, statin therapy does not appear to consistently affect ubiquinone levels in muscle[19], and no direct association between reduced ubiquinone and statin-induced myopathy has been found[25–27]. Exposure of isolated rat skeletal muscle mitochondria to statins in vitro triggers Ca2+-induced opening of the permeability transition pore (PTP) and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm)[21]. In intact cells, elevated calcium levels cause Bax, a pro-apoptotic gene and member of the Bcl-2 family, to translocate to the mitochondria, the mitochondrial PTP to open, and cytochrome c to be released resulting in apoptosis[21, 23, 24]. These findings collectively suggest statins may impair mitochondrial function by an as yet undefined mechanism, leading to an increase in the susceptibility to activation of apoptosis. However, the underlying mechanism(s) by which statins impact mitochondrial function, apoptosis and cell viability, particularly in human muscle cells, remains unknown.

The objectives of this study were thus to: 1) determine the effects of a commonly prescribed lipophilic statin (simvastatin) on cell viability of proliferating (i.e. satellite cells), differentiating (i.e. myoblasts), and differentiated (i.e. myotubes) primary human skeletal muscle cells and morphological changes in primary human myotubes; and 2) determine the effects of simvastatin on mitochondrial respiratory capacity, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial apoptotic cell signaling in primary human skeletal myotubes. We hypothesized that simvastatin would induce cell death in a dose-dependent fashion due to impaired mitochondrial respiration and oxidative stress, leading to mitochondrial apoptotic signaling. In the present study, simvastatin was selected as a representative statin because it has been found to cause myopathy in humans [19–22] and in animal [28–30] models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects and muscle biopsy

Collection of skeletal muscle tissue and subsequent isolation of primary skeletal muscle stem (i.e. satellite) cells occurred at both the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and East Carolina University (ECU). Muscle tissue was collected in the resting state in the morning following an overnight fast (approximately 12 h). Percutaneous needle biopsies of the vastus lateralis were taken with a 5-mm Bergstrom type biopsy needle under local anesthesia (1% lidocaine) using previously described methods[31]. Each biopsy was blotted with gauze and dissected to remove any visible connective and/or adipose tissue. Each subject was provided both oral and written information about the procedure and use of tissue samples for research before giving written informed consent, as approved by the Institutional Review Boards at both UAB and ECU.

Cell viability in primary human cell culture

Biopsied skeletal muscle tissue (65–80mg) was immediately placed into chilled hibernate (BrainBits LLC). Satellite cell isolation occurred within 24 h of tissue collection. Tissue was removed from Hibernate, placed into a petri dish containing sterile 1XPBS, and minced into small pieces. After placing minced tissue into a tube, dissociation media was added and muscle incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. The tissue plus dissociation media were filtered with a cell strainer to remove any non-digested tissue and fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added (v/v). After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) and plated onto a plastic non-coated petri dish to remove fibroblasts and other non-satellite cells. The media, containing the satellite cells, was pipetted off the dish and placed in a tube. After centrifugation, DMEM was aspirated off, and the cells were resuspended in growth media containing Ham’s F12, FBS, fibroblast growth factor, and pen:strep (penicillin: streptomycin solution) and plated on a type I collagen coated plate. The satellite cells were grown to approximately 70–80% confluency in a 37°C humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

Cells were removed from the culture plate using trypsin and counted using Trypan Blue and a hemocytometer. Approximately 13,500 satellite cells were seeded in growth media into individual wells of 96-well plates for 24 h. For the proliferating and differentiating states, after 24 h the cells were washed with PBS and then incubated in growth or differentiation media (Ham’s F12, 2% horse serum, and pen:strep) containing 0.1% DMSO, or 0.05, 0.1, 1.0, 10, or 100 µM simvastatin. For the differentiated state, the cells were allowed to incubate in differentiation media for 48 h prior to being treated with the same concentrations of DMSO or simvastatin.

For all experiments, incubation in simvastatin or DMSO control media occurred for 48 h prior to determining cell viability using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium colorimetric assay (MTS assay). The MTS assay was conducted using the manufacture’s protocol (Promega). Briefly, 20 ul of MTS were added to each well and incubated for 4 hours. Absorbance was recorded at 490 nm. Samples were run in quadruplicate.

To verify that simvastatin effects were due to a disruption in the mevalonate synthesis pathway (i.e. inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase) and not due to toxicity, proliferating and differentiating satellite cells were treated with simvastatin in the presence of mevalonate, the downstream biosynthetic product from the HMG-CoA reductase reaction. After cells were seeded onto 96 well plates for 24 h, proliferating cells were treated with growth media plus 0.1% DMSO (control), 5.0 µM simvastatin, (statin treated), or 5.0 µM simvastatin + 50 µM mevalonate for 48 h. Differentiating cells were treated with differentiation media plus 0.1% DMSO (control), 1.0 µM simvastatin (statin treated), or 1.0 µM simvastatin + 50 µM mevalonate for 48 h. Following 48 h of incubation in each condition, cell viability was determined using MTS assay following the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). In proliferating and differentiating cells, 5.0 µM and 1.0 µM simvastatin (respectively), were the IC50 concentrations and thus, used for the mevalonate viability rescue experiments.

Myotube cell culture and treatment

Skeletal muscle fibers (80–100 mg) obtained from the vastus lateralis were transferred to chilled DMEM, and all visible fat and connective tissues were removed before culture. Cells were suspended in growth media containing DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.5 mg/ml BSA, 0.5 mg/ml fetuin, 20 ng/ml human epidermal growth factor, 0.39 ug/ml dexamethasone, and 50 ug/ml gentamicin/amphotericin B, and cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 and 95% air incubator. After reaching 70–80% confluence, myoblasts were subcultured onto type I collagen-coated plates into two groups with the same cell numbers (statin-treated group and control group). When the myoblasts reached 80% confluence, growth media were switched to differentiation media containing 2% horse-serum, 0.5 mg/ml BSA, 0.5 mg/ml fetuin, and 50 ug/ml gentamicin/amphotericin B for the differentiation of myoblasts into myotubes. After 5 days of differentiation, the myotubes were incubated in differentiation media (+0.1% DMSO) in the presence of simvastatin (5 µM) for an additional 48 h. Control experiments were performed in the presence of only 0.1% DMSO in differentiation media. 5 µM simvastatin in vitro approximates therapeutic doses for patients of approximately 40 – 60 mg/d[32, 33]. Primary human myotubes were harvested on day 7 of differentiation (i.e. 5 d without treatment + 2 d with simvastatin or DMSO treatment) for all experiments. Floating dead cells were removed during media change and were not included in these experiments.

Morphological imaging

Morphological changes and survival of cell numbers were monitored by obtaining photomicrographs under an inverted phase contrast microscope (Olympus America Inc.: Melville, NY) with a digital camera. The cell counting was also performed by Vi-Cell Cell Viability Analyzer (Beckman Coulter: Hialeah, FL).

Preparation of permeabilized cells

After harvesting and counting, the cells were centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min and the cell pellet was treated with 3 µg/106 cells/ml digitonin (i.e. a mild, cholesterol-specific detergent) for 5 min at 37°C with rotation. This procedure selectively permeabilizes the sarcolemmal membranes while keeping mitochondrial membranes, which lack significant levels of cholesterol, completely intact. Following permeabilization, the myotubes were washed by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min to remove endogenous substrates in cells. The permeabilized cells were used for determination of mitochondrial oxygen (O2) consumption, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) emission, and Ca2+ retention capacity (index of PTP susceptibility).

Measurement of mitochondrial O2 respiration

High resolution O2 consumption measurements were conducted at 37°C using the Oroboros Oxygraph-2K (Innsbruck, Austria). After permeabilization and washing, the cells (1.5 × 106 cells per chamber) were placed into a separate chamber with 2 ml of MiR05 respiration buffer [130 mM Sucrose, 60 mM C6H11O7K, 1mM EGTA, 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM K2HPO4, 20 mM HEPES, and 1 mg/ml BSA (pH 7.4)]. With the chambers sealed and upon signal stabilization, the following multiple substrate protocols were commenced for mitochondrial O2 consumption: Protocol I - i) 25 µM palmitoyl carnitine (fatty acid substrate) + 1 mM malate (complex I substrate), ii) 2 mM ADP (state 3 condition), iii) 2 mM glutamate (complex I substrate), iv) 3 mM succinate (complex II substrate), v) 10 µg/ml oligomycin (inhibitor of mitochondrial ATP synthase), and vi) 2 µM carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, a protonophoric uncoupler); and Protocol II: i) 2 mM glutamate + 1 mM malate, ii) 2 mM ADP, iii) 3 mM succinate, iv) 10 µg/ml oligomycin, and v) 2 µM FCCP. The integrity of the outer mitochondrial membrane was confirmed by the absence of increased respiration after cytochrome c addition. In addition, we confirmed the absence of endogenous substrates in the permeabilized myotubes prior to both protocols by washing an aliquot of cells and measuring ADP-stimulated respiration in the absence of added substrates. The rate of O2 consumption was expressed as pmol/sec/million cells.

Measurement of mitochondrial superoxide production

Mitochondrial superoxide (O2•−) was measured in intact cells by flow cytometry (FACS-calibur; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) after staining with mitochondrial O2•− specific dye MitoSOX Red (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as previously reported[34]. Briefly, primary human myotubes were treated with 5 µM simvastatin or 0.1% DMSO (treatment control) for 48 h and with PBS (negative control) or 50 µM Antimycin A (positive control) for 60 min. 5 µM MitoSOX was applied to the treated cells for 30 min at 37°C in CO2 incubator, protected from light. Cells were washed twice with Hank’s Buffered Salt Solution (HBSS) containing calcium and magnesium according to manufacturer’s recommendation. After trypsinization and neutralization with FBS, the cells was counted and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 10 min and then resuspended with FACS buffer (PBS containing 1% BSA, 0.01% NaN3). MitoSOX Red was excited by 488 nm laser and the data were collected at FSC (forward scatter), SSC (side scatter), FL2 (588/42nm), and FL3 (670LP) channel. The data are presented in the FL2 channel. Quantifications were performed using the mean intensity of MitoSOX fluorescence triplicates.

Measurement of mitochondrial H2O2 emission

Mitochondrial H2O2 emission was measured in MiR05 respiration buffer during state 4 respiration (10 µ/ml oligomycin) by continuously monitoring oxidation of Amplex Red using a Spex Fluoromax 3 spectrofluorometer (Jobin Yvon, Ltd.) with temperature control and magnetic stirring at >1000 rpm. After cell permeabilization and washing, fluorescence change due to Amplex Red oxidation (an indicator of H2O2 production) was measured continuously (ΔF/min) at 37°C. After establishing background ΔF (0.5 × 106 cells in the presence of 10 µM Amplex Red, 1U/ml HRP, 10 µg/ml oligomycin, 10 U/ml superoxide dismutase), the reaction was initiated by addition of the multiple substrates including 25 µM palmitoyl-carnitine + 1 mM malate, 2 mM glutamate, 3 mM succinate, and 6.7 µM antimycin A (complex III inhibitor), with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 567 and 587 nm, respectively. H2O2 production rate was calculated from the slope of ΔF/min, after subtracting background from a standard curve established for each reaction condition. The rate of mitochondrial H2O2 emission was expressed as pmol/min/million cells.

Measurement of intracellular ROS generation

Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was measured using carboxyl-2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF-DA) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) with fluorescence microscope as previously reported with modification[35]. Briefly, simvastatin-treated cells were washed with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) and incubated with 500 µM DCF-DA in the loading medium (DMEM +10% FBS) in CO2 incubator at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were washed with HBSS to remove DCF-DA and replaced with loading medium. The fluorescence of the cells was measured using fluorescence microscope (Axiophot2, Carl Zeiss; Thornwood, NY).

Determination of mitochondrial PTP opening

Mitochondrial Ca2+ retention capacity was performed to assess susceptibility of the PTP to opening as previously reported with modification [36]. Briefly, after cell permeabilization and washing, overlaid traces of changes in Ca2+-induced fluorescence by Calcium Green-5 N were measured continuously (ΔF/min) at 37°C during state 4 respiration using a Spex Fluoromax 3 (Jobin Yvon, Ltd.) spectrofluorometer. After establishing background ΔF (0.5 × 106 cells in the presence of 1 µM Calcium Green-5 N, 1 U/ml hexokinase, 0.04 mM EGTA, 1.5 nM Thapsigargin, 5 mM 2-deoxyglucose, 5 mM glutamate, 5 mM succinate, and 2 mM malate), the reaction was initiated by the addition of Ca2+ pulses (12.5 nM), with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 506 and 532 nm, respectively. Total mitochondrial Ca2+ retention capacity prior to PTP opening (i.e., release of Ca2+) was expressed as pmol/million cells.

Determination of apoptotic nuclei in myotubes

TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling) assessment of myonuclei positive for DNA strand breaks was determined using a fluorescence detection kit (Roche Applied Science: Perzberg, Germany) and fluorescence microscopy (Axiophot2, Carl Zeiss; Thornwood, NY) after 48 h of simvastatin (5 µM) or DMSO (0.1%) treatment. Myotubes were grown on glass cover slips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 20 min at room temperature. The myotubes were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 0.1% sodium citrate for 10 min at 4°C. TUNEL reaction mixture containing terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), fluorescein-dUTP was added to the sections in 50 µl drops and incubated for 60 min at 37°C in a humidified chamber in the dark. The myotubes were rinsed three times in PBS for 5 min each and mounted in Vector anti-fade media with DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) to mark all nuclei. The myotubes were then visualized with a fluorescence microscope with parallel positive control (DNase I) and negative controls (label solution only). TUNEL-positive myonuclei were then counted on multiple sections of the myotubes and were expressed as % of all myonuclei (FITC/DAPI × 100).

Immunoblot analysis

Protein levels for Bax and Bcl-2 were determined in the cytosolic protein fraction via Western immunoblot analysis. After 48 h of simvastatin (5 µM) or DMSO (0.1%) treatment, the myotubes were harvested in lysis buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, 10mM EDTA, 100 mM NaF, 50 mM Na pyrophosphate, 10 mM Na orthovanadate supplemented with phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Protein concentration from the cell lysates was determined using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Forty micrograms of protein, from the myotube homogenates, in sample buffer (+5% β-mercaptoethanol), were then loaded into 12.5% polyacrylamide gels and electrophoresed at 150V. The proteins were then transferred at 100V for 2 h onto a PVDF membrane. After staining with Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to verify equal loading and transferring of proteins to the membranes, the membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in Tris buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBS-T) for 4 h. After blocking, membranes were incubated at 4°C in blocking buffer for 12 h with the appropriate primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology: Santa Cruz, CA) and mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-2 (1:250, BD Transduction Laboratories: Lexington, KY). Following 3 washes in TBS-T, membranes were incubated at room temperature for 60 min in blocking buffer with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Following 3 washes in TBS-T, an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Amersham: Piscataway, NJ) was used for visualization. The membranes were stripped and re-probed with GAPDH antibody (1:4000, Advanced Immunochemical: Long Beach, CA) to verify equal loading among lanes as an internal control. Densitometry (i.e. area times grayscale relative to background) was performed using a Kodak film cartridge and film, a scanner interfaced with a microcomputer, and the NIH Image Analysis 1.62 software program.

Statistics

Data are presented as mean ± standard error mean (SEM). Independent t-tests were conducted to test differences between simvastatin-treated cells and DMSO control cells for all measurements (e.g. cell viability, mitochondrial respiration, oxidative stress, protein levels). Additionally, independent, two sample t-tests were used to determine differences between treatment (simvastatin or simvastatin + mevalonate) and DMSO control. Differences were accepted at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Simvastatin reduces the number of viable cells

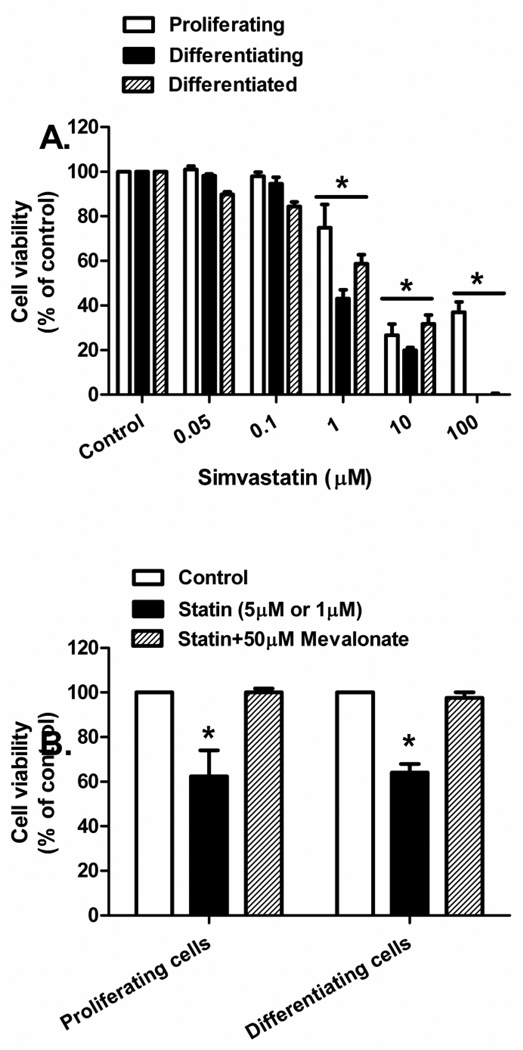

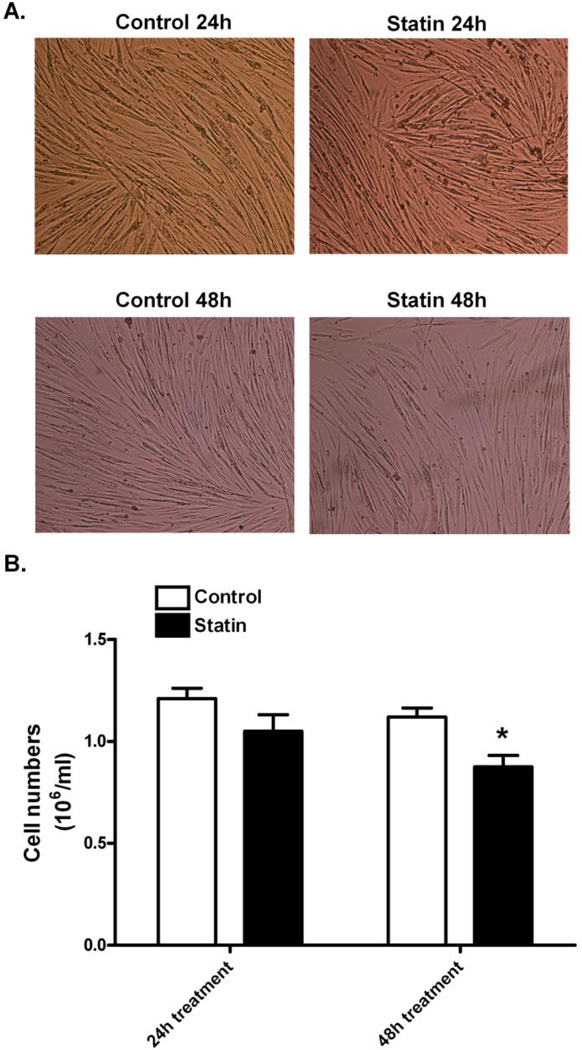

Proliferating, differentiating, and differentiated primary human skeletal muscle cells underwent a dose dependent decrease in cell viability with increasing concentration of simvastatin (Figure 1A). The IC50 for viability approximated 1 µM simvastatin for differentiating cells and 5 µM for the other two cell states. Decreased cell viability was prevented when proliferating (5 µM simvastatin) and differentiating (1 µM simvastatin) cells were treated with 50 µM mevalonate (P<0.05, Figure 1B), indicating that the adverse effect of statins is due specifically to a disruption of the mevalonate biosynthesis pathway and not due to statin toxicity in culture. Changes in the morphology of primary human skeletal myotubes were not visible at 24 h of statin treatment (Figure 2A); however, after 48 h of simvastatin treatment, myotubes appeared less dense and atrophied. Additionally, the statin treated cultures contained 22.3% fewer myotubes at 48 h compared with the DMSO-treated controls (0.87 × 106 vs. 1.12 × 106 cells/ml, respectively, P<0.05, Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Cell viability with simvastatin and mevalonate treatment was measured in primary human skeletal muscle cells. (A) Change in primary human skeletal muscle cell viability following treatment with varying concentrations of simvastatin. *Difference between simvastatin concentration and control (0.1% DMSO) determined within culture conditions (P < 0.05). (B) Change in cell viability following treatment with 5 µM (proliferating satellite cells) and 1 µM (differentiating muscle cells) of simvastatin with and without 50 µM mevalonate. *Different from control and mevalonate treatment (P < 0.05). The data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Figure 2.

Morphological changes from control and simvastatin treated myotubes. (A) Primary human skeletal myotubes were treated with 5 µM simvastatin for 24 h and 48 h and compared with the control myotubes which were treated with 0.1% DMSO. Morphology of primary human skeletal myotubes was viewed at 10X magnification. (B) Cell numbers were determined using Trypan Blue, a hemocytometer, and Cell Viability Analyzer. The data are expressed as means ± SEM. * Different from control (P < 0.05).

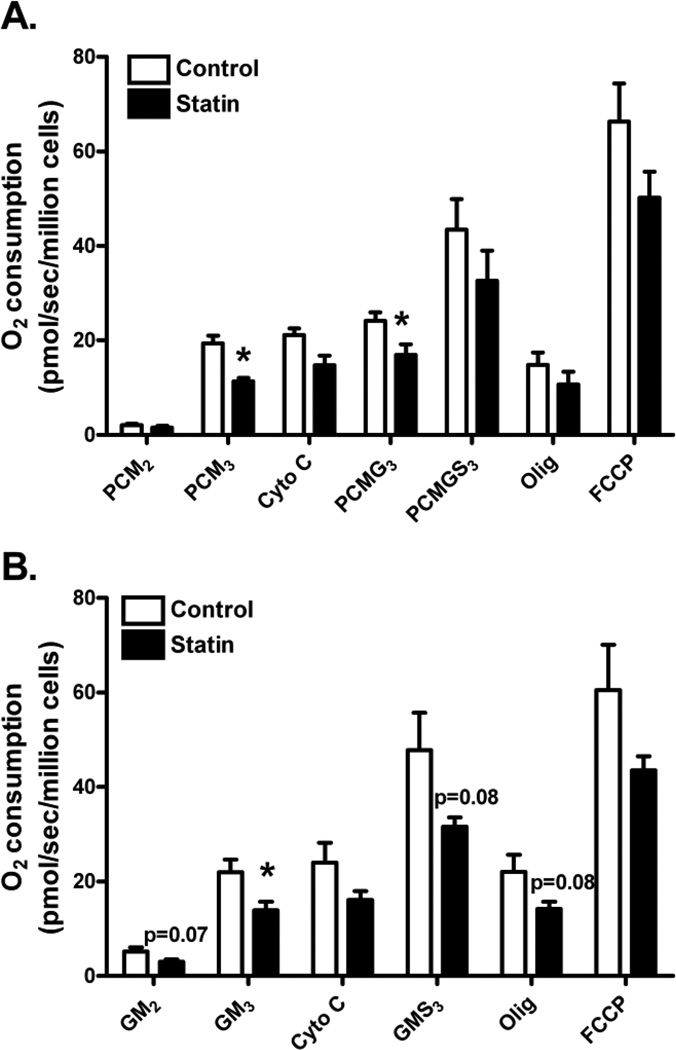

Simvastatin impairs maximal ADP-stimulated mitochondrial respiration

Mitochondrial respiratory capacity, following 48 h of simvastatin or DMSO control treatments, was assessed in intact, digitonin-permeabilized primary human myotubes using two different substrate protocols (see protocols I and II in methods). Mitochondrial respiratory data are based on basal, non-ADP stimulated oxygen consumption (state 2), maximal ADP-stimulated oxygen consumption (state 3), inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthase (state 4), and uncoupling (FCCP). For both treatments (i.e. simvastatin and control) and both protocols, the sequential addition of substrates to the permeabilized myotubes resulted in a gradual increase in O2 consumption during state 3 condition (Figure 3A and 3B). Further increases in O2 consumption were observed with uncoupling by FCCP which followed a dramatic decrease of O2 consumption with inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthase (i.e. oligomycin).

Figure 3.

Simvastatin effects on mitochondrial oxygen (O2) consumption were measured in permeabilized primary human skeletal myotubes from control (open bars) and 5 µM simvastatin treatment (solid bars) during; (A) Protocol I - i) palmitoyl carnitine (fatty acid substrate) + malate (PCM2, complex I substrate), ii) ADP (PCM3, state 3 condition), iii) glutamate (PCMG3, complex I substrate), iv) succinate (PCMGS3, complex II substrate), v) oligomycin (Olig, inhibitor of mitochondrial ATP synthase), and vi) carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, a protonophoric uncoupler); and (B) Protocol II: i) glutamate + malate (GM2), ii) ADP (GM3) iii) 3 succinate (GMS3), iv) oligomycin, and v) FCCP. The data are expressed as means ± SEM. * Different from control (P < 0.05).

Simvastatin treatment did not affect basal (non-ADP stimulated) state 2 respiration in the primary myotubes supported by either palmitoyl-carnitine + malate (PCM2, complex I and II substrates, P>0.05, Figure 3A) and glutamate + malate (GM2, complex I substrates, P=0.07, Figure 3B). However, maximal ADP-stimulated state 3 respiration supported by palmitoyl-carnitine + malate (PCM3) and glutamate + malate (GM3) was significantly reduced (−32% and −37%, respectively, P<0.05) in simvastatin-treated myotubes compared with DMSO control. The addition of cytochrome c in both protocol experiments did not increase O2 consumption which suggests the integrity of the outer mitochondrial membrane remained intact. During respiration supported by PCM, maximal ADP-stimulated respiration remained significantly lower in simvastatin-treated cells upon addition of glutamate (PCMG3, P<0.05, Figure 3A) but was restored by the addition of succinate (PCMGS3, complex II substrate, P>0.05, Figure 3A). Depressed maximal ADP-stimulated respiration supported by GM3 was also at least partially ameliorated by the addition of succinate (P>0.05, Figure 3B) in the statin treated myotubes. Simvastatin did not significantly affect maximal uncoupled, FCCP-stimulated respiration in primary human myotubes (P>0.05, Figures 3A and 3B).

Respiratory control index (RCI) for complex I and II (NADH and FADH2 supply from substrates palmitoyl-carnitine + malate) measured as the ratio of O2 flux with (state 3) and without ADP (state 2) was not different between control and simvastatin-treated myotubes (12.85 ± 3.46 vs. 9.83 ± 2.26, P>0.05, Figure 3A). In addition, RCI for complex I substrate glutamate + malate was not different between control and simvastatin-treated myotubes (4.34 ± 0.58 vs. 5.44 ± 1.06, P>0.05, Figure 3B). Furthermore, there was no difference in citrate synthase activity between control and simvastatin-treated myotubes (9.40 ± 1.08 vs. 9.89 ± 1.04 µmol/g/min, respectively, P>0.05), suggesting differences in respiration induced by statin treatment were not due to overall differences in mitochondrial content.

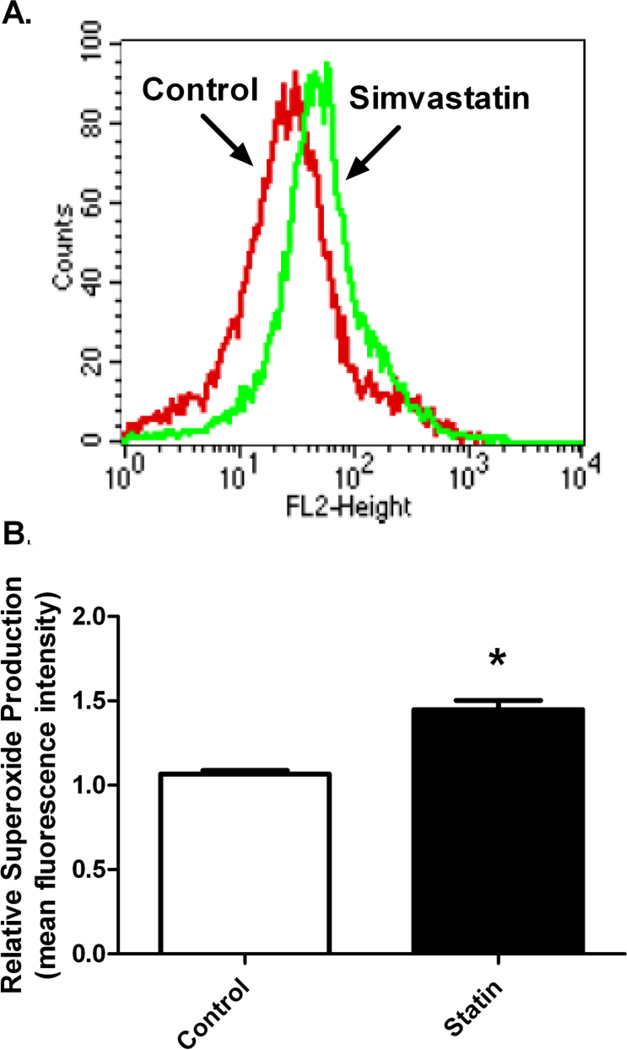

Simvastatin increases mitochondrial oxidative stress

MitoSOX Red fluorescence with flow cytometry was used to measure mitochondrial O2•− (superoxide) generation in primary myotubes treated with simvastatin (Figure 4). Mean fluorescence intensity was markedly elevated in the simvastatin-treated myotubes compared to DMSO control (46.1 vs. 66.5 counts, respectively, Figure 4A). Quantitative measurements of the mean fluorescence intensity of oxidized MitoSOX Red demonstrated approximately 44% increase in O2•− generation following 48 h of simvastatin treatment compared to DMSO control (P<0.05, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Simvastatin effects on mitochondrial superoxide production measured in control and simvastatin treatmented primary human skeletal myotubes. (A) Overlay of representative histograms of flow cytometry experiments from control (DMSO) and statin-treated (5 µM) myotubes showing fluorescence intensity of oxidized MitoSOX Red mitochondrial superoxide (O2•−) indicator. (B) Summary of relative O2•− production in the control and statin treated myotube cultures. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. * Different from control (P < 0.05).

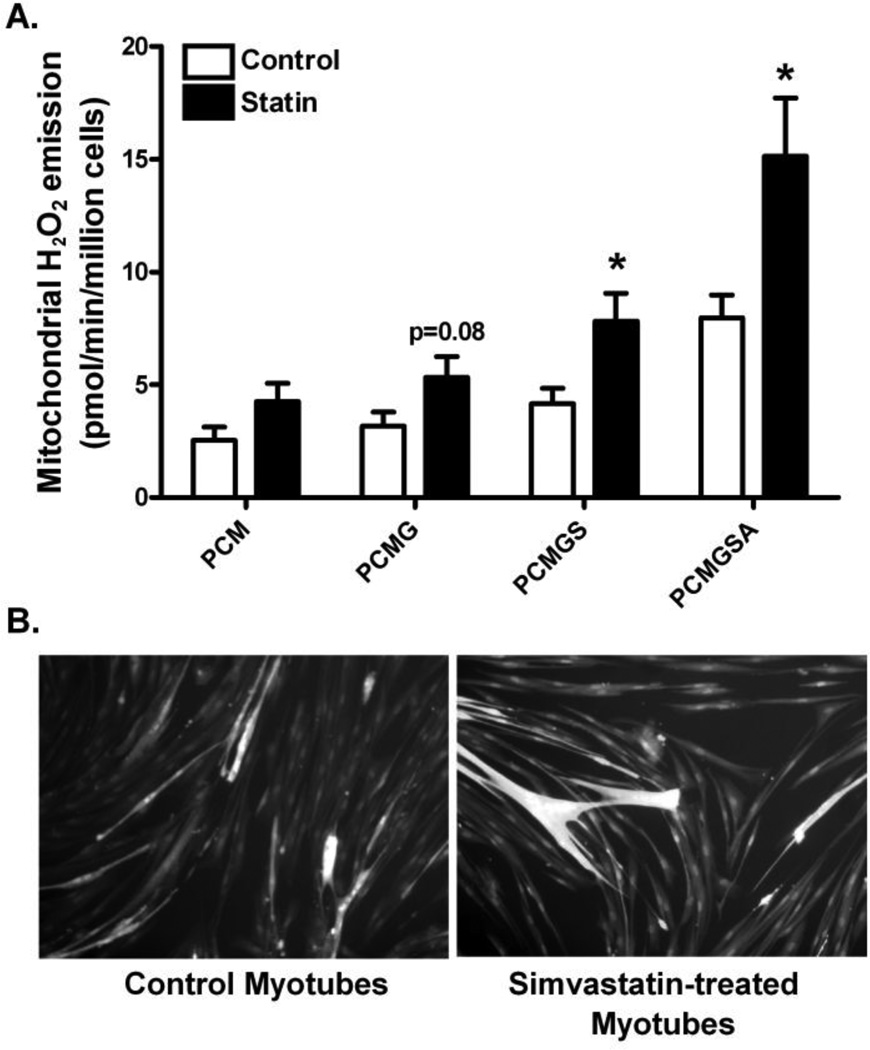

Primary myotubes were permeabilized to determine the effects of simvastatin on mitochondrial H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) emitting potential during basal, state 4 respiration. Simvastatin treatment did not affect mitochondrial H2O2 emission supported by activated fatty acid palmitoyl-carnitine + malate or by the complex I-linked substrate glutamate (P=0.08) in primary human myotubes (Figure 5A). Mitochondrial H2O2 emission did increase by ~90% with addition of the complex II substrate succinate or the complex III inhibitor antimycin A in the statin treated myotubes (P<0.05, Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Simvastatin effects on mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide emission and DCF-DA staining measured in primary human skeletal myotubes from control and simvastatin treatment. (A) Mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) emission by Amplex Red was measured in permeabilized primary human skeletal myotubes following control (0.1% DMSO) and simvastatin treatments (5 µM). (B) Representative images of intracellular ROS production by carboxy-2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCF-DA) with fluorescence microscope. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. * Different from control (P < 0.05).

To confirm ROS production when myotubes are treated with simvastatin, another marker of intracellular ROS production, DCF-DA staining was used. Simvastatin treated myotubes showed increased staining of DCF-DA compared with control in primary human skeletal myotubes (Figure 5B).

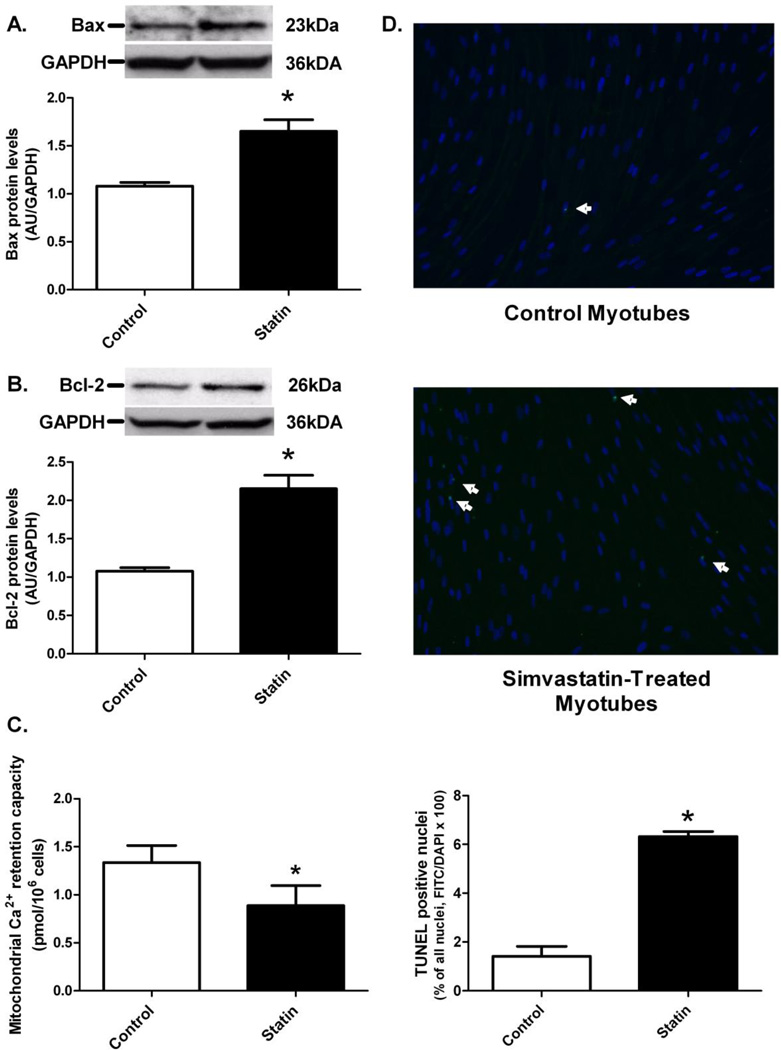

Simvastatin triggers mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in primary human myotubes

Protein levels of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax were 53% higher in the simvastatin treated myotubes compared to control (P<0.05, Figure 6A). Additionally, simvastatin treatment resulted in significantly greater (+100%) Bcl-2 protein levels compared to the DMSO control (P<0.05, Figure 6B). Mitochondrial Ca2+ retention capacity was lower in simvastatin treated myotubes compared with control (P<0.05), which is indicative of approximately 44% increased susceptibility to PTP opening with simvastatin treatment (Figure 6C). Apoptotic nuclei in the primary human myotubes were visualized using the TUNEL method and fluorescence microscopy (Figure 6D). More TUNEL-positive nuclei were observed in the simvastatin treated cultures compared with control (P<0.05).

Figure 6.

Simvastatin effects on (A) Bax protein levels, (B) Bcl-2 protein levels, (C) mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP) opening, and (D) TUNEL-positive nuclei were measured in primary human skeletal myotubes following control (0.1% DMSO) and simvastatin (5 µM) treatments. Immunoblot data were quantified in densitometry units (area × pixel density) per µg muscle protein. Mitochondrial PTP opening, as indicated by the release of Ca2+ in the medium, was measured by the addition of Ca2+ pulses. Representative TUNEL-positive sections (10X magnification) of primary human skeletal myotubes are displayed in (D). * Different from control (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Statins, the vastly prescribed, cholesterol-lowering drugs, induce a number of adverse muscular side effects including declines in skeletal muscle function and strength and increased muscle fatigue, weakness, soreness, and cramps. The mechanistic underpinnings of these reported myopathies are likely multifactorial and involve, at least partially, mitochondrial dysfunction. Statin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction is supported by the present findings in primary human skeletal muscle cells. To our knowledge, these are the first data to indicate that a physiologically relevant dose of simvastatin (5 µM) (~ 40–80 mg/day in vivo dose) 1) impairs ADP-stimulated maximal mitochondrial respiratory function supported by complex I substrates, and 2) increases mitochondrial O2•− and H2O2 emission in primary human skeletal myotubes. In addition, our findings suggest that impairment of complex I by simvastatin may be a primary trigger leading to oxidative stress and apoptosis in human muscle cells, providing a potential mechanism for the skeletal myopathy associated with statin use in humans [29, 36, 37].

Based on previous research[21, 29, 38], which included in vitro statin treatments at levels (>50 µM) that far exceed the peak in vivo muscle statin concentration (<~2–5 µM) resulting from typically prescribed oral doses (20–80 mg)[32, 33], it was unclear whether statins impair mitochondrial respiration. The present results suggest that reduced O2 consumption occurs in primary human skeletal myotubes treated with physiologically relevant doses of simvastatin. Reduced O2 consumption appeared to be primarily mediated by inhibition at complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain as demonstrated by reduced ADP-stimulated, state 3 maximal respiratory capacity supported by both palmitoyl-carnitine + malate and glutamate + malate (Figures 3A and 3B, respectively). Addition of succinate, which supplies electrons directly to the ubiquinone pool, only partially restored maximal state 3 respiration supported by glutamate + malate suggesting that statin treatment may also have some inhibitory effect downstream of complex I. Importantly, citrate synthase activity was nearly identical between statin- and non-statin- treated myotubes, indicating the impaired state 3 respiration induced by statin treatement was not due to differences in mitochondrial content. Impaired state 3 respiration with statin treatment is consistent with results from Sirvent et al.[29] who reported that isolated myofibers, incubated in 50 µM simvastatin, had significantly impaired maximal ADP-stimulated respiration supported by complex I substrates (glutamate + malate). In addition to reduced state 3 respiration, the present data also demonstrate trends for lower complex I linked, basal (i.e. non-ADP-stimulated) state 2 (P=0.07) and state 4 (P=0.08) respiration (Figure 3B).

Mitochondrial dysfunction is associated with the production of oxidative stress in skeletal muscle[39, 40]. In particular, O2•− free radicals produced from complexes I and III in the electron transport chain undergo dismutation by the manganese-isoform of superoxide dismutase (i.e. MnSOD) to form H2O2. The present research is the first direct evidence that simvastatin induces mitochondrial oxidative stress in primary human skeletal myotubes as indicated by greater mitochondrial O2•− production and H2O2 emission as well as other general measures of intracellular ROS generation. The underlying mechanism(s) for the increase in oxidative stress with statin treatment is unclear. One possibility is that statins may induce a deficiency in ubiquinone levels, a particularly attractive hypothesis given that ubiquinone is also synthesized from mevalonate. Ubiquinone is an essential electron carrier between complex I and complex III of the electron transport system and a deficiency could impair electron flow and potentially account for the reduced respiratory capacity and elevated O2•− formation[36, 41]. However, although serum ubiquinone levels are lower with statin treatment, ubiquinone levels in skeletal muscle do not appear to be reduced and clinical evidence demonstrating an efficacy of ubiquinone supplementation is very limited[25–27]. In the present study, addition of succinate to statin-treated permeabilized cells supported exclusively by the complex I substrates glutamate + malate did not restore maximal state 3 respiration to control levels, providing evidence of an inhibitory effect of simvastatin downstream of complex I. In addition, H2O2 emission was elevated in statin-treated permeabilized cells only upon addition of succinate and succinate plus the complex III inhibitor antimycin (Figure 5), consistent with the notion that the ubiquinone cycling sites within complex I and III may be contributing to the elevated ROS emission evident in intact cells (Figure 4). While the mechanism remains unclear at this point, the findings of the current study provide clear evidence of altered mitochondrial function induced by low micromolar exposure to simvastatin in human primary myotubes, raising the possibility that these effects may underlie the skeletal myopathy reported in vivo. Such statin myopathy may be particularly exacerbated by endurance exercise due to the markedly elevated muscle oxidative metabolism, or by activities causing some degree of muscle damage due to disruption of muscle stem (satellite) cell function (leading to inadequate repair).

Oxidative stress plays an important role in a number of physiological functions including cell death, insulin resistance, and activation of NF-kB and proteolytic systems (e.g., calpains, caspase-3, serine protease, ubiquitin/proteosome system)[36, 42–45]. The present results support the hypothesis that ROS generation, induced by statins, triggers mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in differentiated skeletal muscle cells. Indicative of increased apoptosis, the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei was greater in myotube cultures that were incubated with simvastatin (Figure 6D). These results are consistent with previous findings, which indicate enhanced susceptibility for skeletal muscle cell apoptosis and loss when cells are treated with statins[23, 24, 46, 47]. Furthermore, our data clearly indicate that simvastatin dose dependently reduces the number of viable primary human skeletal muscle precursor cells, and induces myotube atrophy (Figures 1 and 2), which is consistent with previous studies[23, 47]. As previously postulated[24, 46], excessive apoptosis could be directly related to myopathy and muscle dysfunction during statin treatment.

Given that oxidative stress and apoptosis were elevated in myotubes treated with simvastatin, we expected that mitochondrial-mediated, pro-apoptotic, Bax protein levels would be similarly elevated. The mitochondrial dysfunction-induced, Bcl-2 family of pro-apoptotic regulatory proteins, which includes Bax, is upstream of caspase-3, a key promoter of apoptosis[48, 49]. Indeed, Bax protein levels were significantly greater in the simvastatin treated myotubes compared with control (Figure 6A), suggesting that statin-induced apoptosis may be mediated by the Bax-Bcl-2 signaling pathway. An increase in Bax may elevate mitochondrial PTP opening and thus increase cytochrome c release, apoptosome formation, and subsequent caspase-9 and caspase-3 activation, promoting DNA fragmentation and cell death[47–49]. In contrast to our hypothesis, we also observed greater protein levels for the anti-apoptotic, Bcl-2 protein in the simvastatin vs. DMSO treated myotubes (Figure 6B), suggesting an attempt to protect against statin-induced cell death.

Mitochondrial Ca2+ retention capacity was also reduced in simvastatin treated human skeletal myotubes, suggesting simvastatin increases the susceptibility of mitochondria to Ca2+ overload-induced PTP opening (Figure 6C). Additionally, we observed impaired complex I-linked maximal ADP-stimulated respiration, increased mitochondrial oxidative stress, and increased pro-apoptotic Bax protein levels, all of which are indicative of increased susceptibility to PTP opening[41, 50] [50, 51] [48]. PTP opening results in collapse of ΔΨm and release of cytochrome c which, together with the adaptor protein Apaf-1, leads to activation of caspase-9[48, 49]. Velho et al. [37] reported that simvastatin increased in vivo and in vitro calcium-dependent mitochondrial PTP opening, raising the possibility that elevated mitochondrial PTP sensitivity to Ca2+ due to elevated ROS production [41], coupled with elevated sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR)/Ca2+ levels [21, 24, 37, 46], may be initiating the programmed cell death in statin treated cells. In this scenario, elevated cytosolic Ca2+ also leads to activation of calpain signaling and translocation of Bax to the mitochondria[23]. Programmed cell death in adult skeletal muscle tissue in response to statin exposure, however, may be more of a progressive rather than an all or none process given that each myofiber is an extremely long multinucleated cell. This would be analogous to the fiber loss that occurs due to aging which appears to occur as a consequence of the progressive loss of mitochondrial function in very distinct regions along the length of the cell, resulting in segmented fiber atrophy eventually culminating in breakage and complete loss of the fiber [52]. While data from the current study provide evidence that statin-induced alterations in mitochondrial function represent the primary event leading to the loss of human myotubes in culture, clearly further research is required to dilineate the underlying mechanism(s) responsible for the acute and potentially cummulative chronic impact of statins on myopathy in adult skeletal muscle tissue.

Conclusions

In summary, simvastatin impaired maximal ADP-stimulated mitochondrial respiration supported by complex I substrates in differentiated primary human skeletal muscle cells. Simvastatin also induced mitochondrial oxidative stress, demonstrated by increased levels of ROS (e.g., O2•−, H2O2) in concert with the up-regulation of the mitochondrial-mediated apoptotic mechanisms (e.g., Bax, PTP opening, TUNEL-positive nuclei) in primary human skeletal myotubes, suggesting that simvastatin induces mitochondrial PTP opening and subsequent cell death through oxidative stress. Future research is necessary to develop counter treatment strategies for statin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress.

Highlights.

Statins can induce muscle weakness/myopathy

In culture, simvastatin induced dose dependent atrophy of human myotubes

Statin exposure decreased mitochondrial respiratory function and increased ROS production

Activation of apoptosis also evident

Findings suggest mitochondrial dysfunction underlies statin-induced myopathy

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Drs. Joseph Houmard and Kristen Boyle for providing access to primary human skeletal muscle cells. This work was supported in part by grants from the United States Public Health Service, RO1 DK075880 (RNC), R01 AG017896 (MMB), RO1 DK073488 (PDN), and RO1 DK074825 (PDN).

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- CoQ10

coenzyme Q10

- DCF-DA

carboxyl-2',7'-dichlorofluorescin diacetate

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- FCCP

carbonylcyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone

- GM

glutamate/malate

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylgutaryl coenzyme A

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- Mn-SOD

manganese superoxide dismutase

- PCM

palmitoyl-carnitine/malate

- PTP

permeability transition pore

- RCI

respiratory control index

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jasinska M, Owczarek J, Orszulak-Michalak D. Statins: a new insight into their mechanisms of action and consequent pleiotropic effects. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59:483–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koh KK, Sakuma I, Quon MJ. Differential metabolic effects of distinct statins. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sewright KA, Clarkson PM, Thompson PD. Statin myopathy: incidence, risk factors, and pathophysiology. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2007;9:389–396. doi: 10.1007/s11883-007-0050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. Jama. 2003;289:1681–1690. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.13.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva M, Matthews ML, Jarvis C, Nolan NM, Belliveau P, Malloy M, Gandhi P. Meta-analysis of drug-induced adverse events associated with intensive-dose statin therapy. Clin Ther. 2007;29:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang JT, Staffa JA, Parks M, Green L. Rhabdomyolysis with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and gemfibrozil combination therapy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13:417–426. doi: 10.1002/pds.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinzinger H, O'Grady J. Professional athletes suffering from familial hypercholesterolaemia rarely tolerate statin treatment because of muscular problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57:525–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson PD, Zmuda JM, Domalik LJ, Zimet RJ, Staggers J, Guyton JR. Lovastatin increases exercise-induced skeletal muscle injury. Metabolism. 1997;46:1206–1210. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, Rader DJ, Rouleau JL, Belder R, Joyal SV, Hill KA, Pfeffer MA, Skene AM. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1495–1504. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr, Stone NJ. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demyanets S, Kaun C, Pfaffenberger S, Hohensinner PJ, Rega G, Pammer J, Maurer G, Huber K, Wojta J. Hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors induce apoptosis in human cardiac myocytes in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:1324–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guijarro C, Blanco-Colio LM, Ortego M, Alonso C, Ortiz A, Plaza JJ, Diaz C, Hernandez G, Egido J. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase and isoprenylation inhibitors induce apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells in culture. Circ Res. 1998;83:490–500. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson TE, Zhang X, Bleicher KB, Dysart G, Loughlin AF, Schaefer WH, Umbenhauer DR. Statins induce apoptosis in rat and human myotube cultures by inhibiting protein geranylgeranylation but not ubiquinone. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;200:237–250. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnaboldi L, Guzzetta M, Pazzucconi F, Radaelli G, Paoletti R, Sirtori CR, Corsini A. Serum from hypercholesterolemic patients treated with atorvastatin or simvastatin inhibits cultured human smooth muscle cell proliferation. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellosta S, Arnaboldi L, Gerosa L, Canavesi M, Parente R, Baetta R, Paoletti R, Corsini A. Statins effect on smooth muscle cell proliferation. Semin Vasc Med. 2004;4:347–356. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-869591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Vliet AK, Negre-Aminou P, van Thiel GC, Bolhuis PA, Cohen LH. Action of lovastatin, simvastatin, and pravastatin on sterol synthesis and their antiproliferative effect in cultured myoblasts from human striated muscle. Biochem Pharmacol. 1996;52:1387–1392. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(96)00467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veerkamp JH, Smit JW, Benders AA, Oosterhof A. Effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on growth and differentiation of cultured rat skeletal muscle cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1315:217–222. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(95)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Pinieux G, Chariot P, Ammi-Said M, Louarn F, Lejonc JL, Astier A, Jacotot B, Gherardi R. Lipid-lowering drugs and mitochondrial function: effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on serum ubiquinone and blood lactate/pyruvate ratio. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;42:333–337. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.1996.04178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paiva H, Thelen KM, Van Coster R, Smet J, De Paepe B, Mattila KM, Laakso J, Lehtimaki T, von Bergmann K, Lutjohann D, Laaksonen R. High-dose statins and skeletal muscle metabolism in humans: a randomized, controlled trial. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;78:60–68. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips PS, Haas RH, Bannykh S, Hathaway S, Gray NL, Kimura BJ, Vladutiu GD, England JD. Statin-associated myopathy with normal creatine kinase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:581–585. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirvent P, Mercier J, Vassort G, Lacampagne A. Simvastatin triggers mitochondria-induced Ca2+ signaling alteration in skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329:1067–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaist D, Rodriguez LA, Huerta C, Hallas J, Sindrup SH. Lipid-lowering drugs and risk of myopathy: a population-based follow-up study. Epidemiology. 2001;12:565–569. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200109000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sacher J, Weigl L, Werner M, Szegedi C, Hohenegger M. Delineation of myotoxicity induced by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase inhibitors in human skeletal muscle cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:1032–1041. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.086462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sirvent P, Mercier J, Lacampagne A. New insights into mechanisms of statin-associated myotoxicity. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2008;8:333–338. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marcoff L, Thompson PD. The role of coenzyme Q10 in statin-associated myopathy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2231–2237. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaars CF, Stalenhoef AF. Effects of ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10) on myopathy in statin users. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:553–557. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283168ecd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaklavas C, Chatzizisis YS, Ziakas A, Zamboulis C, Giannoglou GD. Molecular basis of statin-associated myopathy. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierno S, Didonna MP, Cippone V, De Luca A, Pisoni M, Frigeri A, Nicchia GP, Svelto M, Chiesa G, Sirtori C, Scanziani E, Rizzo C, De Vito D, Conte Camerino D. Effects of chronic treatment with statins and fenofibrate on rat skeletal muscle: a biochemical, histological and electrophysiological study. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:909–919. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sirvent P, Bordenave S, Vermaelen M, Roels B, Vassort G, Mercier J, Raynaud E, Lacampagne A. Simvastatin induces impairment in skeletal muscle while heart is protected. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:1426–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westwood FR, Bigley A, Randall K, Marsden AM, Scott RC. Statin-induced muscle necrosis in the rat: distribution, development, and fibre selectivity. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33:246–257. doi: 10.1080/01926230590908213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans WJ, Phinney SD, Young VR. Suction applied to a muscle biopsy maximizes sample size. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:101–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baer AN, Wortmann RL. Myotoxicity associated with lipid-lowering drugs. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:67–73. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328010c559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bellosta S, Paoletti R, Corsini A. Safety of statins: focus on clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Circulation. 2004;109:III50–III57. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131519.15067.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Yoshihiro K, Hasko G, Pacher P. Simple quantitative detection of mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:612–616. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin CT, Price JW, 3rd, Kang L, Rabinovitch PS, Szeto HH, Houmard JA, Cortright RN, Wasserman DH, Neufer PD. Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:573–581. doi: 10.1172/JCI37048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Velho JA, Okanobo H, Degasperi GR, Matsumoto MY, Alberici LC, Cosso RG, Oliveira HC, Vercesi AE. Statins induce calcium-dependent mitochondrial permeability transition. Toxicology. 2006;219:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufmann P, Torok M, Zahno A, Waldhauser KM, Brecht K, Krahenbuhl S. Toxicity of statins on rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2415–2425. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gianni P, Jan KJ, Douglas MJ, Stuart PM, Tarnopolsky MA. Oxidative stress and the mitochondrial theory of aging in human skeletal muscle. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1391–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yokota T, Kinugawa S, Hirabayashi K, Matsushima S, Inoue N, Ohta Y, Hamaguchi S, Sobirin MA, Ono T, Suga T, Kuroda S, Tanaka S, Terasaki F, Okita K, Tsutsui H. Oxidative stress in skeletal muscle impairs mitochondrial respiration and limits exercise capacity in type 2 diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1069–H1077. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00267.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fontaine E, Eriksson O, Ichas F, Bernardi P. Regulation of the permeability transition pore in skeletal muscle mitochondria. Modulation By electron flow through the respiratory chain complex i. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12662–12668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawler JM, Song W, Demaree SR. Hindlimb unloading increases oxidative stress and disrupts antioxidant capacity in skeletal muscle. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:9–16. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powers SK, Kavazis AN, DeRuisseau KC. Mechanisms of disuse muscle atrophy: role of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R337–R344. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00469.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid MB. Response of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to changes in muscle activity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R1423–R1431. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00545.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siu PM, Wang Y, Alway SE. Apoptotic signaling induced by H2O2-mediated oxidative stress in differentiated C2C12 myotubes. Life Sci. 2009;84:468–481. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dirks AJ, Jones KM. Statin-induced apoptosis and skeletal myopathy. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C1208–C1212. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00226.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi M, Kaido F, Kagawa T, Itagaki S, Hirano T, Iseki K. Preventive effects of bicarbonate on cerivastatin-induced apoptosis. Int J Pharm. 2007;341:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antonsson B. Mitochondria and the Bcl-2 family proteins in apoptosis signaling pathways. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;256–257:141–155. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000009865.70898.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Detaille D, Guigas B, Chauvin C, Batandier C, Fontaine E, Wiernsperger N, Leverve X. Metformin prevents high-glucose-induced endothelial cell death through a mitochondrial permeability transition-dependent process. Diabetes. 2005;54:2179–2187. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Odagiri K, Katoh H, Kawashima H, Tanaka T, Ohtani H, Saotome M, Urushida T, Satoh H, Hayashi H. Local control of mitochondrial membrane potential, permeability transition pore and reactive oxygen species by calcium and calmodulin in rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wanagat J, Cao Z, Pathare P, Aiken JM. Mitochondrial DNA deletion mutations colocalize with segmental electron transport system abnormalities, muscle fiber atrophy, fiber splitting, and oxidative damage in sarcopenia. Faseb J. 2001;15:322–332. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0320com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]