Abstract

This review addresses peer group influences on adolescent smoking with a particular focus on recently published longitudinal studies that have investigated the topic. Specifically, we examine the theoretical explanations for how social influence works with respect to adolescent smoking, discuss the association between peer and adolescent smoking; consider socialization and selection processes with respect to smoking; investigate the relative influence of best friends, close friends, and crowd affiliations; and examine parenting behaviors that could buffer the effects of peer influence. Our review indicates the following with respect to adolescent smoking: (1) substantial peer group homogeneity of smoking behavior; (2) support for both socialization and selection effects, although evidence is somewhat stronger for selection; (3) an interactive influence of best friends, peer groups and crowd affiliation; and (4) an indirect protective effect of positive parenting practices against the uptake of adolescent smoking. We conclude with implications for research and prevention programs.

Keywords: Adolescents, smoking, peer influence, literature review

Introduction

Adolescent smoking

The prevalence of smoking increases dramatically during adolescence (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, and Schulenberg 2007). While not all experimental users increase their uptake over time (Abroms, Simons-Morton, Haynie, and Chen 2005; Tucker, Klein, and Elliott 2004), early initiation increases the likelihood of habituation, leading to a host of negative outcomes (Pierce and Gilpin 1995). Therefore, prevention of initiation and progression is an important national health objective (U.S.Department of Health and Human Services 2000). The development of effective prevention programs depends on a firm understanding of the factors associated with adolescent smoking.

Social influences are among the most consistent and important factors associated with adolescent smoking (Kobus 2003). Social influences are important with respect to a wide range of health behaviors, including medication taking (Berkman 2000), diet (Larson, Neumark-Sztainer, Hannan, and Story 2007), sexual intercourse (Henry, Schoeny, Deptula, and Slavick 2007), and substance use (Kobus 2003). Adolescents may be particularly susceptible to social influences given their developmental stage and the importance of school and peer groups in adolescent life (Steinberg and Monahan 2007). Moreover, there may be uniquely social aspects of adolescent smoking and other substance use, in that other adolescents provide access, opportunity, and reinforcement (Kirke 2004; O'Loughlin, Paradis, Renaud, and Gomez 1998). Therefore, it should not be surprising that adolescent substance use and peer use are highly associated. While the effects of peer groups on adolescent substance use have been widely documented, much remains to be learned, especially regarding the mechanisms of peer influence (Kobus 2003).

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to review and summarize the literature on peer group influences on adolescent smoking, building on the several recent reviews of the topic (Hoffman, Monge, Chou, and Valente 2007; Kobus 2003; Tyas and Pederson 1998), and focusing on the recent publications on smoking. We conducted Internet searches with Web of Science and other search engines using key words such as “adolescent smoking,” “adolescent substance use,” “longitudinal studies,” “peer influence,” “socialization,” and “selection.” To be included in this review, studies had to have been published in 1999 or more recently; be longitudinal; include adolescent smoking as an outcome (either separately, or investigated within the context of adolescent substance use); and include measures of peer smoking at a minimum of two time points.

To provide a useful framework for the discussion of social influence, in general, and peer influence, in particular, on smoking, the paper is organized around the following key questions: What is social influence? What are the theoretical explanations for how social influence works? To what extent does peer smoking predict adolescent smoking? Are adolescents influenced by their friends (socialization) or do adolescents select friends with similar interests (selection) with respect to smoking? Are best friends, close friends, or crowd affiliations more important? Do positive parenting behaviors buffer the effects of peer influence?

Conceptual and theoretical perspectives on social influences on behavior

What is social influence?

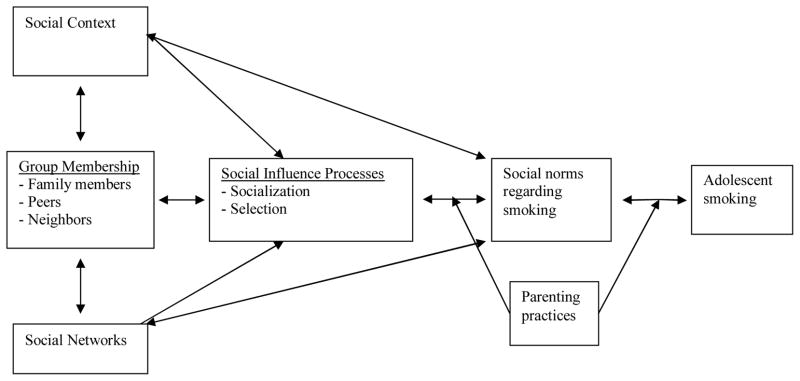

Social influence is the effect others have on individual and group attitudes and behavior (Berkman 2000). A conceptualization of multi-level social influences on adolescent smoking is presented in Figure 1. The conceptualization suggests that social influences on adolescent smoking are exerted through social context, social networks, and group membership that operate mainly on social norms. Details of these constructs and of the relationships between them are presented in the following paragraphs.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for social influences on adolescent smoking

Social norms are the patterns of acceptable beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (Axelrod 1984; Kameda, Takezawa, and Hastie 2005). Because human development occurs very slowly, individuals are socialized over time by family, school, and community and religious institutions according to the prevailing social norms. Social norms are influenced by – but also influence – social context, group membership, and social networks. The social influence processes that facilitate these reciprocal relationships between social norms and social structures are socialization and selection. Briefly, socialization is the tendency for individuals’ norms and behaviors to be influenced by the norms and behaviors of one’s group and conforming to them. Selection, however, refers to the tendency of individuals to seek-out peers with similar norms and behaviors (Simons-Morton 2007).

Social context refers to the opportunities for interaction and the contexts within which individual interaction occurs (Webster, Freeman, and Aufdemberg 2001). Social context determines the breadth, extent and nature of interpersonal interaction and therefore shapes the interpretation of social norms. As noted, humans are social creatures who live in families, reside in neighborhoods, belong to religious organizations, attend school, and go to work, all social enterprises through which most social interactions occur and which define the social context. Direct and primary social influence is thought to occur mainly within individuals’ proximal social context, which includes the family and peer groups (Dawkins 1989). Our experiences and the information we gain in these settings shape our understanding of what is normative and acceptable behavior and train us in social relations (Dawkins 1989).

Social context determines opportunity for social interaction through social network formation. In its simplest form, a social network is a map of all of the relevant ties between individuals and groups (Valente, Gallaher, and Mouttapa 2004). One’s social network consists of all the people and groups with whom one has contact and the nature and extent of social interactions. The formation of each person’s social network is largely determined by shared social context such as neighborhood, school, church, and family (Wilcox 2003). Social networks are important because connected people share information and shape each other’s perceptions of social norms. However, it is not just who individuals’ know or how often they spend time with them, but the nature of relationships (closeness, reciprocity, frequency of contact) that also contributes to social influence (Valente, Gallaher, and Mouttapa 2004).

Group membership (e.g., family, religious, school, peer) is a particularly powerful socializing experience and people often change their perceptions, opinions, and behavior to be consistent with standards or expectations (norms) of the group (Forgas and Williams 2001; Kameda, Takezawa, and Hastie 2005). Peer group affiliation becomes particularly important and influential during adolescence (Brown 1989). Being a friend or part of a larger group, such as a clique, classroom, grade, school, club, or activity; or loosely affiliating with an amorphous crowd with similar interests (e.g., sports, music, drugs) provides great benefits of acceptance, friendship, and identity, but can also demand conformity (Brown 1989). Group members tend to share common attitudes and behavior and this is particularly true for adolescent peer groups (Eiser, Morgan, Gammage, Brooks, and Kirby 1991). Substance use is one factor about which friends and groups of adolescents tend to come to agreement, leading to group homogeneity (Kandel 1978), although there may be periods of adolescence when peer influence is greatest (Eckhardt, Woodruff, and Edler 1994; Steinberg and Monahan 2007). Susceptibility to peer influences may vary by gender and race (reviewed in Hoffman, Monge, Chou, and Valente 2007).

In summary, adolescents experience a range of social influences that may provide some direct effects on the likelihood of substance use, including smoking, but mainly provide indirect effects through social norms. In this section, we have presented social context, social networks, and group membership as discrete sources of influence; however, they are highly overlapping and interactive. As proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1979), it may be useful to think of the strength of various social influences as depending on proximity and frequency of contact, where the closest circles of influence include the people with whom adolescents associate most of the time (family and peers) and whose influence on their behavior, particularly smoking, is likely to be the greatest.

What are the theoretical explanations of how social influence contributes to adolescent smoking?

No one theory fully explains social influence, but many theories emphasize that people learn through social interaction. A substantial discussion of theory is beyond the scope of the present review, and other papers have presented excellent overviews of theory relating to adolescent smoking uptake (Hoffman, Monge, Chou, and Valente 2007; Kobus 2003). However, it may be useful here to point out the centrality of social norms in the prominent theories typically used to design research and explain findings on peer group effects. Social cognitive theory (Bandura 1996) emphasizes the importance of cognitive representations in the form of expectations about social norms that arise from observational and experiential learning. Reasoned action (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975) emphasizes the importance of perceived social (subjective) norms on intentions. Primary socialization (Oetting and Donnermeyer 1998) and social bonding theories (Hirschi 1969) suggest that adolescent peer group effects will be stronger in the absence of strong social bonds with family and school. Social identity theory (Terry, Hogg, and White 2000) suggests that adolescents try on various identities and adopt the norms that are central to the social identity of the peer group to remain in good standing. Similarly, social exchange theory (Kelley and Thibaut 1985) argues that friendships and group membership requires fair exchanges (reciprocity), leading to conformity of behavior between friends and group members. Of course, the nature of the relationships of group members greatly influences the nature of this reciprocity (Plickert, Cote, and Wellman 2007). Social network theory suggests that social norms are shaped by information shared among members of a social system (Scott 2000; Valente 1995). Norms also figure prominently in the literature on persuasion and social marketing (Hastings and Saren 2003). Indeed, social influence is the basis for two-stage communication strategies in which persuasive communications are directed not at the ultimate target, but at opinion leaders whose attitudes and behavior influence others in their social groups (Rogers, 2003). Urberg et al. (2003) described the two-stage model of social influence as it applies to adolescent substance use.

Each of these theories shares the perspective that close (proximal) relationships provide a primary social influence, while the media and other aspects of culture provide important but secondary influences. Close relationships are most important because they are persistent, valued, and emotional. Individuals interact more often and spend more time with close relationships, and time spent together provides opportunities for influence. Each of these theories also recognizes that adolescents develop perceptions about social norms from information sharing (via interaction or observation) with people and groups in their social environment. In brief, social influence is implicit or explicit in many psycho-social theories and is one of the most consistently considered phenomenon in social psychology and persuasion (Terry and Hogg 2000).

Peer group homogeneity with respect to adolescent smoking

To what extent does peer group smoking predict adolescent smoking?

The tendency for adolescent peer group members to share common characteristics such as smoking, termed alternatively as peer group clustering or homogeneity, has been well described (Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, and Li 2002; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook 2001; Alexander, Piazza, Mekos, and Valente, 2001). Good evidence of this association comes from studies using prospective research designs, which allow the researcher to determine if peer use predicts future adolescent use, thereby providing stronger evidence of causality than cross-sectional associations. Indeed, research using prospective designs assess adolescent and peer substance use at baseline (Time 1) and adolescent substance use at follow up (Time 2 or at multiple time points), providing a test of the extent to which peer substance use predicts eventual adolescent use, while controlling for adolescent baseline use. Through standard literature review procedures (as discussed in the introduction), we identified 40 prospective studies published since 1999 linking peer group smoking or measures of substance use that include smoking, to future adolescent use.

Despite a wide range of differences in methods and populations studied, all but one of the papers reviewed reported positive associations between peer use at Time 1 and adolescent smoking at follow-up, including the following: (a) 23 of 24 papers that examined the relationship of friend smoking or smoking as part of a measure of substance use at Time 1 and smoking or substance use at follow-up; (b) all nine papers that examined the relationship between grade-level prevalence at Time 1 and smoking at follow up (Bricker, Andersen, Rajan, Sarason, and Peterson 2007; Eisenberg and Forster 2003; Ellickson, Bird, Orlando, Klein, and Mccaffrey 2003; Ellickson, Perlman, and Klein 2003; Epstein, Griffin, and Botvin 2000; Mccabe, Schulenberg, Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, and Kloska 2005; Rodriguez, Romer, and Audrain-McGovern 2007; Spijkerman, van den Eijnden, and Engels 2005); (c ) all five papers that reported both friend and grade level prevalence (Epstein, Bang, and Botvin 2007; Gritz, Prokhorov, Hudmon, Jones, Rosenblum, Chang, Chamberlain, Taylor, Johnston, and De Moor 2003; Simons-Morton and Haynie 2003b; Simons-Morton 2002; Smet, Maes, De Clercq, Haryanti, and Winarno 1999); (d) and all three papers that examined the influence of friend use at Time 1 on adolescent smoking trajectory groups (Abroms, Simons-Morton, Haynie, and Chen 2005; Vitaro, Wanner, Brendgen, Gosselin, and Gendreau 2004; Wills, Resko, Ainette, and Mendoza 2004). All previous articles examined smoking as a distinct outcome, with the exception of the article by Wills et al (2004), which considered smoking as part of a substance use composite score. To better illustrate the influence of peer smoking on adolescent smoking, we describe select findings in the subsequent paragraphs.

Does peer group influence on adolescent smoking vary by adolescent subgroups?

A main finding emerging from this literature points to the variation of peer influence on adolescents’ smoking by socio-demographic characteristics. While gender differences are well established, with girls shown to be more strongly influenced by peer smoking than boys (Griffin et al., 1999), age differences were less clear. For example, Vitaro et al. (2004) found that friend use predicted adolescent smoking progression in the peer 12–13 and 13–14 year old groups, but not in the 11–12 year old groups. Conversely, Abrams and colleagues (2005) found that 6th graders (age=11 years) with friends who smoke were more likely over time to become intenders, experimenters, or regular smokers.

This literature also provides valuable information on peer group effects in minority populations. Several studies found that African-American youth with friends who smoke were more likely to initiate smoking over time than those with no such friends (Brook, Pahl, and Ning 2006; White, Violette, Metzger, and Stouthamer-Loeber 2007). Similarly, positive associations between friends’ smoking and adolescent smoking were observed among Latino (Livaudais et al., 2007) and Chinese (Chen et al., 2006) adolescents. A comparison of peer influence by race/ethnicity yields conflicting findings, with studies showing less effect of peer smoking on adolescent smoking among African-American than White adolescents (Ellickson, Perlman, and Klein 2003; Robinson, Murray, Alfano, Zbikowski, Blitstein, and Klesges 2006); while others reporting similar peer group influence for White, Black, and Hispanic students (Gritz, 2003). The different findings could be due to differences in samples by age or geographic location.

Peer group influence also varies by individual characteristics including genetics, which could influence exposure to substance-using friends (Cleveland, Wiebe, Rowe, 2005); and personal attributes such as competency skills (Epstein et al., 2007), or perceptions of personal harm due to smoking (Rodriguez et al.,2007). Finally, peer influences on smoking may be moderated by strong social bonds to school and family (Ellickson, Perlman, Klein, 2003).

Overall, this literature is surprisingly consistent in reporting positive associations between peer smoking and future adolescent smoking, and provides evidence that peer behavior affects initiation, progression, and trajectories. It also documents the influence of peer use on adolescent use among adolescents of various race and ethnicity groups, and shows that this influence may be mediated or moderated by cognitions, gender, and maturation. This research provides substantial evidence that smoking among friends predicts adolescent future smoking, but modest evidence that general prevalence, for example, within a particular grade or school, predicts future smoking, with the exception though, of cases where a higher general prevalence of smoking among senior students is related to an increase in smoking among lower-grade students (Leatherdale, Cameron, Brown, Jolin Kroeker, 2006). However, while this literature bettered our understanding of peer influence on adolescent smoking, it does not address how peer group influences actually work.

The research on peer influence is limited by the fact that it is not possible to determine the extent to which friendships in existence at study initiation were formed due to selection or socialization processes. These friendships that are already in place at the beginning of a study would have been influenced by past socialization and selection processes that would be difficult or impossible to determine (Cohen and Syme 1985). However, beyond that caveat, it can reasonably be assumed that associations between friends who smoke and smoking uptake are evidence of socialization and associations between smoking status and increases in the number of smoking friends is evidence of selection.

Are adolescents influenced (socialized) by their friends or do adolescents select friends with similar interests (selection) with respect to smoking?

The processes by which peer influence leads to peer group homogeneity of behavior are socialization and selection. Socialization is the tendency for attitudes and behavior to be influenced by the actual or perceived attitudes and behavior (e.g., norms) of ones’ friends and the conforming properties of group membership. Selection, on the other hand, is the tendency to affiliate and develop friendships with those who have similar attitudes and common interests (Simons-Morton 2007).

Peer socialization

Peer socialization is the effect of existing social relationships on the formation of social norms. With socialization, the group accepts an adolescent based on shared characteristics. To be accepted, the adolescent takes on the attitudes and behaviors of the group (Evans, Powers, Hersey, and Renaud 2006). Peer socialization can be overt, as in peer pressure, or perceived, where the adolescent accepts or changes attitudes and behavior based on perceived group norms that may or may not be actual. Socializing processes that facilitate the uptake of adolescent smoking can also discourage use (Stanton, Lowe, and Gillespie 1996).

Peer socialization is often referred to as peer pressure, a term that suggests that adolescents directly persuade their friends to conform to their behavior. However, peer pressure is only one aspect of socialization. While there is evidence that adolescents do offer their friends cigarettes and that smoking is typically initiated in the context of peers (Kirke 2004; Lucas and Lloyd 1999; Robinson, Dalton, and Nicholson 2006), most of the evidence indicates that socialization is mainly a normative process and not one of overt peer pressure. In surveys, youth report that overt peer pressure is not a factor for their smoking, but report that they sometimes experience internal pressure to smoke in the presence of other adolescents who are smoking, an evidence for the influence of perceived social norms rather than overt peer pressure (Nichter, Nichter, Vuckovic, Quintero, and Ritenbaugh 1997). These findings suggest that perceived social norms exert a socializing effect.

Social norms need only be perceived to influence behavior. It has been shown that adolescents sometimes perceive that the prevalence of smoking is higher among their peers than they are in actuality (Bauman and Ennett 1996; Iannotti, Bush, and Weinfurt 1996), which may be due to several possible factors. Adolescents may psychologically project their own smoking behavior onto others, thereby overestimating smoking prevalence (Miller, Monin, and Prentice 2000). Adolescents may also develop a false consensus that one’s attitudes and behavior are normative when they are not (Berkowitz 2004).

Overall, it seems that socialization occurs mainly through indirect pressure to conform through actual or perceived social norms. Although direct and overt peer pressure almost certainly operates, there is substantially less empirical evidence of its importance compared with the indirect influence on social norms.

Peer selection

Unlike socialization, where the person conforms to group norms, selection occurs when an individual seeks or affiliates with a friend or group with common attitudes, behaviors, or other characteristics. Selection processes include de-selection. When some members of a peer group begin smoking or experimenting with other substances, other members of the peer group can respond by dropping out of the group (de-selection), conforming to the new group norm (socialization), risking group disapproval, or living with the dissonance between their norms and the group’s (Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, and Li 2002).

Selection may be abstract and internal, when a person affiliates with others by identifying with them or with what they represent, rather than affiliating on the basis of observable behaviors. For example, adolescents may identify with groups according to musical preferences, reputation, or interests (ter Bogt, Engels, and Dubas 2006). Such affiliations may be highly transient among adolescents. Selection also involves actual affiliation and, within the limits of their social network, people gravitate toward individuals or groups who share their interests and values, and provide a supportive context for their own views and behavior (Urberg, Degirmencioglu, and Tolson 1998). Adolescents who are interested in smoking, for example, may select as friends adolescents with similar interests in smoking (Ennett and Bauman 1994), although smoking may be just one manifestation of a constellation of social norms leading to social selection.

Recent evidence regarding effects of selection and socialization on smoking

While selection and socialization processes can operate independently, they may also be interactive. Previous reviews have noted that some studies have found support for selection, some for socialization, and some for both with respect to adolescent smoking uptake (Hoffman, Monge, Chou, and Valente 2007; Kobus 2003). However, there has been considerable disagreement about the relative importance of these two processes (Arnett 2007; Bauman and Ennett 1996; Ennett and Bauman 1994).

To examine the latest findings on the topic, we reviewed published studies not included in previous reviews, using the methodology outlined in the introduction. Of the 13 papers reviewed (several papers were unique analyses of separate questions asked of the same data), seven used structural equation, general linear equation, or latent growth modeling; two used cross-lagged auto-regressive analyses to evaluate adolescent and peer substance use relationships from year to year; and four studies employed social network methods. All these methods are particularly useful for sorting out the effects of socialization and selection.

The findings of the first seven studies in Table 1 used latent growth modeling or similar analyses. All studies examined adolescent smoking as a distinct outcome, with the exception of Wills and Cleary’s study (1999), where smoking was part of a substance use composite score. Evidence of socialization or selection is based on the longitudinal relationships between peer and adolescent substance use: Peer smoking at Time 1 predicting an increase in adolescent smoking over time, would be evidence of socialization, whereas adolescent smoking at Time 1 predicting peer smoking over time would be evidence of selection. However, when viewed from the perspective of adolescents’ influence on peer smoking, rather than the reverse, an increase over time in peer smoking would be socialization. The findings were mixed, with one study reporting effects only for socialization, five studies reporting effects for selection only, and three studies reporting effects of both socialization and selection. Wills and Cleary (1999) found effects of socialization and not selection on a combined measure of smoking, drinking, and marijuana use. DeVries et al. (2003), Simons-Morton et al. (2004), DeVries et al. (2006), and Hoffman et al. (2007) found evidence of selection, but not of socialization on smoking progression. Urberg et al. (2003) found effects of both socialization and selection on smoking and drinking, Mercken et al. (2007) found effects of both processes on smoking, and Audrain-McGovern et al. (2006) found a direct effect on smoking progression of socialization and an indirect effect of selection through growth over time in friends who smoke.

Table 1.

| Author and Year | Sample and Location | Adolescent Use Measure (Outcome) | Peer Use Measure | Assessment | Analyses | Significant Findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Growth Model, General Linear Equation, Structural Equation Modeling | |||||||

| Wills, Cleary, 1999 | 1190 7th graders The US; New York metropolitan area |

Frequency of use of tobacco, alcohol or marijuana (composite measure) Having more than three drinks on one occasion in the past month |

Number of friends who smoke cigarettes, drink beer or wine, smoke marijuana |

Respondents

Questionnaires at three time points (3-year follow-up) Peers Respondents’ reports at all three time points |

Analyze peer-influence vs. peer selection mechanisms in adolescent tobacco, alcohol and marijuana use Analysis strategy Latent growth modeling; multiple regression |

Peer smoking associated with change in adolescent smoking Adolescent smoking did not increase friends who smoke |

Evidence of socialization No evidence of selection |

| De Vries, | 15705 adolescents; mean age = 13.6 Six European countries: Denmark, Finland, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, UK |

|

A three-point scale for best friend (yes, maybe, no). A five-point scale for friends in general (all, more than half, half, less than half, hardly anybody). |

Respondents

Questionnaires at two time points Peers Participants’ report of their friends’ smoking at two time points |

Assess the relationship between smoking behaviors of adolescents and smoking status of their parents and friends. Analysis strategy Multiple regression analyses |

Longitudinal regression analysis showed that the β coefficients of the smoking status of the best friend and friends in general were comparable to that of parental smoking. | No evidence of socialization Evidence of selection |

| Simons-Morton, Chen, Abroms, Haynie, 2004 | 1320 6th graders The US; Maryland |

Frequency of smoking in the past 30 days and past 12 months | Number of five closest friends who smoke Number of five closest friends who drink, cheat on a test, bully someone, act disrespectfully, steal, lie to parents, damage property |

Respondents

Questionnaires at five time points (3-year follow-up) Peers Respondents’ reports at all time points |

Examine associations between initial and continuing peer affiliation and parent influences and smoking stage progression Analysis strategy latent growth curve; lagged autoregressive latent trajectory analyses |

Consistency between adolescents and peers in smoking at baseline and over time. Protective effect of authoritative parenting practices on the formation of friends who smoke |

No evidence of socialization Evidence of selection |

| Audrain-McGovern, Rodriguez, Tercyak, Neuner, Moss, 2005 | 918 9th graders The US; Northern Virginia |

Variable measuring smoking progression that includes: never smokers, puffers, experimenters, current smokers and frequent smokers | Composite measuring smoking among nine best friends:

|

Respondents

Questionnaires at 5 time points (4-year follow-up) Peers Respondents’ reports at 4 time points |

Determine whether self-control had indirect effects on smoking practices through effects on peer smoking Analysis strategy Latent curve growth modeling |

Evidence that peer smoking directly influences adolescent smoking progression Problems with impulse control increased likelihood of having peer who smokes, indirectly increasing smoking likelihood at baseline; opposite effect for increased planning |

Evidence of socialization Indirect effect of selection |

| De Vries, Candel, Engels, Mercken, 2006 | 7102 adolescents; mean age of 12.78 years Six European countries: Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Spain and Portugal |

Weekly smoking | Best friend ever smoking Number of friends who smoke |

Respondents Questionnaires at two time points (1-year interval) Peers Adolescents’ reports of their friends’ smoking at two time points |

Examine the influence of friends’ smoking at Times 1 and 2 on respondents’ smoking at Time 2 Analysis strategy Structural Equation Modeling |

No association between friends’ smoking at T1 and adolescent smoking at T2 for most countries. Significant positive association between adolescent smoking at T1 and friends’ smoking at T2 |

No evidence for socialization Evidence of selection |

| Mercken, Candel, Willems, DeVries, 2007 | 1886 adolescents; mean age of 12.7 years. The Netherlands |

Average # cigarettes smoked during week | Average # cigarettes smoked during week |

Respondents

Questionnaires at two time points (1 year interval) Peers Self-reported smoking of five best friends attending the same school at two time points |

Examine the influence of friends’ smoking at Times 1 and 2 on respondents’ smoking at Time 2 Analysis strategy Structural Equation Modeling |

Within non-reciprocal friendships, effect of social selection Within reciprocal friendships, effect of socialization and to a lesser extent, social selection |

Evidence of socialization Evidence of selection |

| Hoffman, Monge, Chou, Valente, 2007 | 20,747 participants in Add Health 7th– 12th grade The US; National |

Ever tried smoking | Number of friends who smoke at least one cigarette a day, out of three best friends |

Respondents

Questionnaires at two time points (1-year follow-up) Peers Respondents’ reports at both time points |

Test a model of peer influence and peer selection on ever smoking by adolescents Analysis strategy Structural equation modeling |

Smoking at Time 1 was more strongly associated with peer smoking at Time 2 than Time 1 peer smoking with Time 2 adolescent smoking | No evidence of socialization Evidence of selection |

| Auto-regressive analyses | |||||||

| Simons-Morton, Chen, 2006 | 2453 6th graders The US; Maryland |

Frequency of smoking, drinking, marijuana use past 30 days (composite measure) | Number of five closest friends who smoke, drink, or use marijuana |

Respondents

Questionnaires at five time points (3-year follow-up) Peers Respondents’ reports at all time points |

Examine reciprocal influence of adolescent and peer substance use from one time point to the next Analysis strategy lagged autoregressive latent trajectory analyses |

Great consistency between adolescents and peers in substance use over time. Evidence of reciprocal effects of peer use leading to adolescent use and adolescent use leading to peer use. |

Socialization was a less consistent predictor than selection |

| Tucker, Martinez, Ellickson, Edelen, 2008 | 6527 7th graders The US; Oregon |

Composite measuring quantity and frequency of smoking | Best friend smoking Frequency the participant is around kids who are smoking cigarettes |

Respondents

Questionnaires at four time points (10-year follow-up) Peers Respondents’ reports at all time points |

Investigate the temporal associations of adolescent smoking with pro- smoking family and peer influences Analysis strategy Path analyses of cross- lagged effects |

Stronger effect of youth smoking on friendship formation than the reverse Household smoking and parent approval predicted smoking, while parent disapproval was negatively associated with future smoking and friendships with smokers |

Reciprocal influences Socialization effects less consistent over time than selection effects |

| Social Network Analyses | |||||||

| Maxwell, 19 2002 | 69 adolescents, aged 12–18 The US; national sample |

Current smoking, marijuana use and chewing tobacco (30past days) (separate outcomes) Current drinking (past 12 months) |

Current smoking, marijuana use and chewing tobacco (past 30 days) Current drinking (past 12 months) |

Respondents

Questionnaires at two time points (1-year follow-up) Peers Self-reported at both time points (one same- sex friend per participant, among all nominated friends) |

Examine peer influence across five risk behaviors: cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, marijuana use, tobacco chewing, and sexual debut Analysis strategy Logistic regression |

Random same sex peer behavior predicted teen smoking and marijuana initiation and alcohol initiation and discontinuation Friends protect against risk activities as well as promote initiation |

Evidence of socialization Did not measure selection |

| Urberg, Luo, Pilgrim, Degirmencioglu, 2003 | 1028 6th, 8th and 10th grade (some attrition for future waves) The US, Midwest |

Ever use of cigarettes or alcohol (separate outcomes) Current use of cigarettes or alcohol Frequency of drunkenness in the past month |

Same as adolescent use measures. Computed for best friends and other friends |

Respondents

Questionnaire at 4 time points (3-year follow- up) Peers Friends’ reports at all time points |

Assess (1) the initial selection of cigarette- and alcohol using peers and (2) influence from peers Analysis strategy Hierarchical regressions |

Adolescents with low school achievement value or little time with parents more likely to choose friends who smoked High peer acceptance and high friendship quality associated with greater adolescent conformity to friend’s substance-use |

Evidence of socialization Evidence of selection |

| Kirke, 2004 | 267 adolescents, aged 14-18 Ireland |

Ever use of cigarettes, alcohol and drugs (separate outcomes ) | Ever use of cigarettes, alcohol and drugs |

Respondents Questionnaire at one time point (use information about when the friendship was formed) Peers Self-reported from nominated friends |

Examine relative impact of peer influence and selection on similarity in the substance use Analysis strategy Social network analysis |

Similarity in the substance use of adolescents is due to both peer socialization influence and selection Greater role of peer influence. |

Evidence of socialization Evidence of selection |

| Hall, Valente, 2007 | 1960 6th graders Location not specified |

Ever trying smoking, even a few puffs | Ever trying smoking, even a few puffs |

Respondents

Questionnaires at three time points (1-year follow-up) Peers Self-reported at all time points (from 5 best friends) |

Examine the processes of peer socialization and selection on adolescent smoking Analysis strategy Social network analysis |

Nominating smokers as friends predicted future smoking Being nominated as a friend provided indirect influence on future smoking |

Evidence of indirect effect of socialization Evidence of selection |

Some of the studies have included other risk behaviors (generally other substance use), in addition to smoking

All of the included studies are longitudinal except for Kirke, 2004; but this study was included because of its importance in addressing the socialization/selection paradigm

Two studies used auto-regressive analyses where the cross-lagged relationship between adolescent and peer smoking (Tucker et al., 2008) or substance use (Simons-Morton and Chen, 2006) at each time point was examined. Both studies found evidence of reciprocal effects of socialization and selection. Tucker et al. (2008) found evidence for both selection and socialization on smoking, with stronger effects for selection than socialization. Simons-Morton and Chen (2006) found similar magnitude of effects, but a more consistent effect of selection than socialization on a combined measure of adolescent and peer substance use.

The four social network studies found effects of socialization and the three that assessed selection also found evidence of selection. Urberg et al. (2003) reported effects of both selection and socialization on adolescent substance use. Maxwell (2002) reported effects of both socialization and selection on smoking, drinking, and chewing tobacco. Kirke (2004) reported that Irish adolescents tended to have common substance use behaviors over time, with selection a somewhat stronger effect than socialization. Hall and Valente (2007) reported direct effects of selection and indirect effects of socialization on smoking.

Findings of these studies with advanced study designs suggest that both socialization and selection processes contribute to peer group homogeneity with respect to smoking, probably in some sort of syncopation (Urberg, Luo, Pilgrim, and Degirmencioglu 2003), with rather stronger evidence for selection than socialization. Effects were found for a variety of populations and varying measures of both peer and adolescent substance use. These modern designs and methods provide stronger evidence and richer findings than the traditional prospective analyses, where future adolescent substance use is predicted by current peer use.

Methodologies for investigating socialization processes: Comparative assessment

Growth modeling provides an elegant test of the relationship of peer use at Time 1 to the growth in adolescent use (socialization) and adolescent use at time 1 on peer use over time (selection), and these studies provided stronger support for selection than socialization. The findings of the two studies that used autoregressive approaches indicated that the magnitude of the effect of selection is relatively consistent but the effect of socialization varies over time, which suggests that these processes may be interactive and may vary by age or friendship dynamics.

Social network analyses are informative because they follow the same adolescents and peers over time, thus overcoming the objection that growth model analyses may over-estimate selection effects to the extent that adolescents’ reports of their friends’ substance use may be projections rather than true measures of friend use (Arnett 2007; Bauman and Ennett 1996; Iannotti, Bush, and Weinfurt 1996). It is particularly interesting that the social network studies reviewed consistently demonstrated effects of both socialization and selection (where measured), similar to the findings of previous social network studies (Ennett, Bauman, and Koch 1994). Social network studies can also provide unique information about the nature of peer influence that cannot be learned from other designs. For example, Urberg et al. (2003) reported that reciprocal friendships provided greater influence than non-reciprocal friendships, consistent with theory (Plickert, Cote, and Wellman 2007) and other research (Terry, Hogg, and White 2000). Also, Kirke (2004) demonstrated among Irish adolescents that adolescent smoking is a highly social activity in that adolescents smoke in groups and offer and borrow cigarettes.

Collectively, the studies reviewed provide strong evidence for peer influence effects on adolescent smoking, suggest that selection is at least as important as socialization, and that these two processes are probably interactive. However, more can be learned about the nature of peer influence processes and how they might vary by age, gender, race, and friendship qualities and what factors mediate the relationship between adolescent and peer smoking.

Are best friends, close friends, or crowd affiliations more important?

While substantial information exists on the independent influences of best friends and peer groups on adolescent smoking, few studies have examined the differential impact of these relationships. Establishing a close relationship with one friend and belonging to a peer group are thought to be more or less equally important for adolescents and both types of relationships may facilitate essential developmental tasks such as the building of social skills, identity formation, and social support (Giordano 2003). Yet, best friends and peer groups may not equally influence adolescents’ behavior. If influence results from wanting to please friends, then best friends would be expected to be more influential. However, if influence derives from the desire to conform to the group norms, then peer group influence would be expected to supersede the influence of one close friend (Urberg, Degirmencioglu, and Pilgrim 1997).

Only four studies were identified that examined whether best friendships and peer groups function differently to affect adolescent smoking and other substance use. Several findings emerged from these studies. First, the influence of a best friend as compared to the influence of a group of friends varied depending on the behavior under consideration (best friend’s influence was greatest for behaviors that are illegal), and the stage of use (best friends predicted initation whereas the peer group predicted transition to current use) (Urberg, Degirmencioglu, and Pilgrim 1997). Second, best friendships and peer groups interacted to better predict adolescent use (Hussong 2002). For example, adolescents with substance-using best friends showed a decreased risk for substance use if they had other close friends who were not high substance-users. However, the influence of a best friend was shown to be independent of peer groups in another investigation (Alexander, Piazza, Mekos, and Valente, 2001). Finally, adolescents with reciprocal friendships within a group were less influenced by the overall level of smoking among the group than adolescents with no reciprocal friendships (Aloise-Young, Graham, and Hansen 1994).

Crowd affiliation has been identified as another source of influence on adolescent smoking (Engels, Scholte, van Lieshout, de Kemp, and Overbeek 2006; Michell 1997; Michell and Amos 1997; Urberg, Shyu, and Liang 1990). Each crowd has a reputation that allows adolescents to recognize youth who share similar beliefs, attitudes and behaviors. As adolescents affiliate with specific crowds, they tend to embrace the behaviors of the crowd, perhaps as a result of their perceptions of the crowd’s reputation, rather than direct peer pressure from crowd members (Kobus 2003).

The prevalence of smoking varies considerably between youth crowds. Crowds that are perceived as “deviant” or unconventional, are likely to have the highest smoking rates (La Greca, Prinstein, and Fetter 2001; Schofield, Pattison, Hill, and Borland 2003; Verkooijen, de Vries, and Nielsen 2007). Reasons for smoking also vary across crowds, and can range from the maintenance of high social status to the need to climb up in the hierarchy (Michell and Amos 1997). The association between crowd membership and smoking can best be explained by social identity theory, which emphasizes the importance of group membership for adolescents’ self-identity. Accordingly, adolescents affiliated with a crowd are likely to be influenced by the crowd’s norms and will tend to adopt the crowd’s normative behaviors (Verkooijen, de Vries, and Nielsen 2007).

In summary, best friends, peer groups and social crowds all appear to affect adolescents’ smoking and other substance use. While few studies have examined whether their effects are independent or interactive, results suggest that effects are dependent on (1) the specific substance used; (2) the stage of use; and (3) relationship characteristics (e.g., adolescent is member of the group but not central to it). More research is needed to clarify the mechanisms through which these influence processes occur, particularly using national samples, to allow for the simultaneous evaluation of the effects of best friends, peer groups and social crowds across a range of substances and for different demographic subgroups.

Do positive parenting behaviors buffer the effects of peer influence?

Parent influence has frequently been found to be associated with adolescent smoking. However, associations have generally been modest (Avenevoli and Merikangas 2003). Household smoking has been identified as a modest predictor of adolescent smoking (Hoffman, Monge, Chou, and Valente 2007; Kobus 2003). But it is not clear if this effect is due to increased availability of cigarettes, modeling, or parenting practices. Prospective studies have shown protective effects of a variety of positive parenting practices (Simons-Morton and Haynie 2003a), including setting expectations (Abroms, Simons-Morton, Haynie, and Chen 2005; Forrester, Biglan, Severson, and Smolkowski 2007; Simons-Morton 2004; Tucker, Klein, and Elliott 2004) parent support (Simons-Morton 2007; Simons-Morton 2004; Wills, Resko, Ainette, and Mendoza 2004) and parental monitoring (Dishion and Andrews 1995; Mounts and Steinberg 1995; Simons-Morton 2007; Simons-Morton, Chen, Abroms, and Haynie 2004). The effect of positive parenting practices may be influenced by the strength of family ties (Urberg, Luo, Pilgrim, and Degirmencioglu 2003) Parents and peers appear to provide independent effects on smoking (Simons-Morton and Haynie 2003a). However, of the few studies that have examined both peer and parent effects, most indicate that peers provide greater influences on adolescent smoking than parents (Hoffman, Monge, Chou, and Valente 2007).

One mechanism by which parents can protect their children from smoking and other undesired behaviors is to discourage their association with friends who engage in these behaviors, provide bad examples, and otherwise exert negative socializing influences, as indicated in Figure 1. Several studies have demonstrated that parent influence on adolescent smoking occurs indirectly by preventing friendship formation with smoking peers (Avenevoli and Merikangas 2003; Simons-Morton, Haynie, Crump, Eitel, and Saylor 2001), moderating the effects of friend influence (Dielman, Butchart, and Shope 1993), or moderating affiliation with smoking peers (Engels and van der Vorst 2003). Urberg (2003) reported that teens who value their parents are less likely to select substance-using friends. Several recent studies reported that positive parenting practices and parent-teen relationship factors reduce likelihood of adolescents forming friendships with substance using peers, providing indirect protective effects on adolescent smoking (Simons-Morton 2004; Tucker, Martínez, Ellickson, and Edelen 2008).

Limitations of existing literature

While there are many papers on peer influences on adolescent smoking and other substance use, a limited number of papers have reported prospective findings in which both peer and adolescent smoking were assessed. For example, few such papers have compared the relative effects of best friend, close friends, or general peer group. There is also a paucity of research on social influences among ethnic groups. Further, while current studies examining the effects of socialization and selection suggest that an increase in smoking uptake at Time 2 by the number of friends who smoked at Time 1 is evidence of socialization, and that an increase in friends who smoke at Time 2 among adolescents who smoke at Time 1 provides evidence of selection, the two processes may not be that distinct and are actually interactive. More information is, however, needed regarding the circumstances surrounding socialization and selection. For example, a smoker at Times 1 and 2 with non-smoking friends at Time 1 but with friends who smoke at Time 2 may illustrate selection (choosing new friends) or socialization (influencing Time 1 friends to smoke) processes, that could only be disentangled through gathering more information about group composition and dynamics over time. Finally, many studies have used a measure of substance use that includes smoking and other substance use, usually drinking, sometimes marijuana use. The main advantage of this convention is it allows for the configuration of a continuous or ordinal measure, with many analytic advantages over nominal measures of smoking. However, this convention makes it impossible to know the relative influences on smoking compared with overall substance use.

Summary

In this manuscript, we provided a conceptual model showing social influence on adolescent smoking occurring at multiple levels. Within this context we discussed the literature on proximal social influences on adolescent smoking, including peer and parent influences. Based on this review we offer the following tentative conclusions.

There is substantial peer group homogeneity with respect to adolescent smoking and other substance use. This is to say that adolescents with friends who smoke are likely to smoke themselves or to take up smoking over time. The reverse is also the case that adolescents without friends who smoke are less likely to take up smoking than adolescents with friends who smoke.

Both socialization and selection appear to provide important influence on adolescent smoking. They also appear to be interactive. The evidence from studies based on advanced research designs is somewhat stronger for selection than socialization effects.

Best friends appear to provide the greatest peer influence on adolescent smoking; peer groups (close friends) provide independent influence, but their influence may also interact with that of the best friend. Crowd affiliation is another friendship dimension that appears in limited research to be associated with adolescent substance use. It is modestly associated with adolescents’ smoking and may interact with peer group influence. Few studies have examined the relative influence of best friends, peer groups and crowd affiliations and a more research is needed.

Parenting appears to remain an important influence on adolescent smoking during adolescence, with parental smoking increasing the likelihood of adolescent smoking and protective parenting practices that are maintained over time providing both direct and indirect (by reducing the number or influence of smoking friends) protective effects against the uptake of adolescent smoking.

Implications and future directions

We believe the rich literature on the effects of peer and parent influences on adolescent smoking, while incomplete, provides a strong basis for the development of next generation prevention programs. Based on the literature, interventions might be designed that focus on cognitive factors that might mitigate the effects of peer group influences, as some social skills-oriented programs have emphasized (Haegerich, Tolan, 2008), or they might be directed at the peer group and designed to alter social norms, or they could be directed at facilitating protective parenting practices.

Future research on peer influences on adolescent smoking would benefit from further examination of the relative effects of best friend, close friends and general peer group, especially among adolescent subgroups (for e.g., by gender, age, race/ethnicity). Further, examining the effects of socialization and selection deserves continued attention, as methodological advances (e.g., social network analyses software) and more refined study designs (e.g., longitudinal studies following-up adolescents and their peer group) facilitate the differentiation of these two processes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the intramural research program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

References

- Abroms L, Simons-Morton B, Haynie DL, Chen RS. Psychosocial predictors of smoking trajectories during middle and high school. Addiction. 2005;100:852–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander C, Piazza M, Mekos D, Valente T. Peers, schools, and adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;29(1):22–30. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloise-Young PA, Graham JW, Hansen WB. Peer Influence on Smoking Initiation During Early Adolescence - A Comparison of Group Members and Group Outsiders. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1994;79:281–287. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.79.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Li F. The influence of peers on young adult substance use. Health Psychology. 2002;21:349–357. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. The myth of peer influence in adolescent smoking initiation. Health Education and Behavior. 2007;34:594–607. doi: 10.1177/1090198105285330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Audrain-McGovern J, Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Neuner G, Moss HB. The impact of self-control indices on peer smoking and adolescent smoking progression. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31:139–151. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Familial influences on adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98:1–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod R. The evolution of cooperation. New York: Basic Books; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Ennett ST. On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: commonly neglected considerations. Addiction. 1996;91:185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF. Social support, social networks, social cohesion and health. Social Work in Health Care. 2000;31:3–14. doi: 10.1300/J010v31n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD. An overview of the social norms approach. In: Lederman L, Stewart L, Goodhart F, Laitman L, editors. Changing the culture of college drinking: a socially situated prevention campaign. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Andersen MR, Rajan KB, Sarason IG, Peterson AV. The role of schoolmates' smoking and non-smoking in adolescents' smoking transitions: a longitudinal study. Addiction. 2007;102:1665–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Pahl K, Ning YM. Peer and parental influences on longitudinal trajectories of smoking among African Americans and Puerto Ricans. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:639–651. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BB. The role of peer groups in adolescents' adjustment to secondary school. In: Berndt TJ, Ladd GW, editors. Peer relationships in child development. New York: Wiley; 1989. pp. 188–215. [Google Scholar]

- Chen XG, Stanton B, Fang XY, Li XM, Lin DH, Zhang JT, Liu HJ, Yang HM. Perceived smoking norms, socioenvironmental factors, personal attitudes and adolescent smoking in China: a mediation analysis with longitudinal data. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:359–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Wiebe RP, Rowe DC. Sources of exposure to smoking and drinking friends among adolescents: A nehavioral-genetic evaluation. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2005;166:153–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Syme SL. Social support and health. Orlando: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins R. The selfish gene. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries H, Candel M, Engels R, Mercken L. Challenges to the peer influence paradigm: results for 12–13 year olds from six European countries from the European Smoking Prevention Framework Approach study. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:83–89. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.007237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries H, Engels R, Kremers S, Wetzels J, Mudde A. Parents' and friends' smoking status as predictors of smoking onset: findings from six European countries. Health Education Research. 2003;18:627–636. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dielman TE, Butchart AT, Shope JT. Structural equation model tests of patterns of family interaction, peer alcohol use, and intrapersonal predictors of adolescent alcohol use and misuse. Journal of Drug Education. 1993;23:273–316. doi: 10.2190/8YXM-K9GB-B8FD-82NQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Andrews DW. Preventing escalation in problem behaviors with high-risk young adolescents: immediate and 1-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:538–548. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt L, Woodruff SI, Edler JP. A Longitudinal Analysis of Adolescent Smoking and Its Correlates. Journal of School Health. 1994;64:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1994.tb06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Forster JL. Adolescent smoking behavior - Measures of social norms. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25:122–128. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiser JR, Morgan M, Gammage P, Brooks N, Kirby R. Adolescent health behaviour and similarity-attraction: friends share smoking habits (really), but much else besides. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1991;30:339–348. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1991.tb00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Bird CE, Orlando M, Klein DJ, Mccaffrey DE. Social context and adolescent health behavior: Does school-level smoking prevalence affect students' subsequent smoking behavior? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:525–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Perlman M, Klein DJ. Explaining racial/ethnic differences in smoking during the transition to adulthood. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:915–931. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00285-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels RC, Scholte RH, van Lieshout CF, de Kemp R, Overbeek G. Peer group reputation and smoking and alcohol consumption in early adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engels Rutger CME, van der Vorst Haske. The Roles of Parents in Adolescent and Peer Alcohol Consumption. The Netherlands journal of sociology. 2003;39:53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE. The contribution of influence and selection to adolescent peer group homogeneity: the case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Koch GG. Variability in cigarette smoking within and between adolescent friendship cliques. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:295–305. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Bang H, Botvin GJ. Which psychosocial factors moderate or directly affect substance use among inner-city adolescents? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Griffin KW, Botvin GJ. A model of smoking among inner-city adolescents: The role of personal competence and perceived social benefits of smoking. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:107–114. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans WD, Powers A, Hersey J, Renaud J. The influence of social environment and social image on adolescent smoking. Health Psychology. 2006;25:26–33. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas JP, Williams KD. Social influence: direct and indirect processes. Philadelphia: Psychology Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester K, Biglan A, Severson HH, Smolkowski K. Predictors of smoking onset over two years. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9:1259–1267. doi: 10.1080/14622200701705357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano PC. Relationships in adolescence. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:257–281. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Doyle MM, Diaz T, Epstein JA. A six-year follow-up study of determinants of heavy cigarette smoking among high-school seniors. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;22:271–284. doi: 10.1023/a:1018772524258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritz ER, Prokhorov AV, Hudmon KS, Jones MM, Rosenblum C, Chang CC, Chamberlain RM, Taylor WC, Johnston D, De Moor C. Predictors of susceptibility to smoking and ever smoking: A longitudinal study in a triethnic sample of adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2003;5:493–506. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000118568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegerich TM, Tolan PH. Core competencies and the prevention of adolescent substance use. New directions for child and adolescent development. 2008;122:47–60. doi: 10.1002/cd.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Valente TW. Adolescent smoking networks: The effects of influence and selection on future smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:3054–3059. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings G, Saren M. The Critical Contribution of Social Marketing: Theory and Application. Marketing Theory. 2003;3:305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Henry DB, Schoeny ME, Deptula DP, Slavick JT. Peer selection and socialization effects on adolescent intercourse without a condom and attitudes about the costs of sex. Child Development. 2007;78:825–838. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BR, Monge PR, Chou CP, Valente TW. Perceived peer influence and peer selection on adolescent smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1546–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM. Differentiating peer contexts and risk for adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti RJ, Bush PJ, Weinfurt KP. Perception of friends' use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana among urban schoolchildren: A longitudinal analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 1996;21:615–632. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future: national survey results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2006. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kameda T, Takezawa M, Hastie R. Where do social norms come from? The example of communal sharing. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:331–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Similarity in real-life adolescent friendship pairs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1978;36:306–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut JW. Self-Interest, Science, and Cynicism. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1985;3:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Kirke DM. Chain reactions in adolescents' cigarette, alcohol, and drug use: similarity through peer influence or the patterning of ties in peer networks. Social Networks. 2004;26:3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kobus K. Peers and adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98:37–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Prinstein MJ, Fetter MD. Adolescent peer crowd affiliation: Linkages with health-risk behaviors and close friendships. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2001;26:131–143. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Family meals during adolescence are associated with higher diet quality and healthful meal patterns during young adulthood. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:1502–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale ST, Cameron R, Brown KS, Jolin MA, Kroeker C. The influence of friends, family, and older peers on smoking among elementary school students: Low-risk students in high-risk schools. Preventive Medicine. 2006;42(3):218–222. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livaudais JC, Napoles-Springer A, Stewart S, Kaplan CP. Understanding Latino adolescent risk behaviors: Parental and peer influences. Ethnicity & Disease. 2007;17:298–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas L, Lloyd B. Starting smoking: girls' explanations of the influence of peers. Journal of Adolescence. 1999;22:647–655. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell KA. Friends: the role of peer influence across adolescent risk behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:267–277. [Google Scholar]

- Mccabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Kloska DD. Selection and socialization effects of fraternities and sororities on US college student substance use: a multi-cohort national longitudinal study. Addiction. 2005;100:512–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Mercken L, Candel M, Willems P, De Vries H. Disentangling social selection and social influence effects on adolescent smoking: the importance of reciprocity in friendships. Addiction. 2007;102:1483–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell L. Loud, sad or bad: Young people's perceptions of peer groups and smoking. Health Education Research. 1997;12:1–14. doi: 10.1093/her/12.1.1-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell L, Amos A. Girls, pecking order and smoking. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44:1861–1869. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00295-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DT, Monin B, Prentice DA. Pluralistic ignorance and inconsistency between private attitudes and public behaviors. In: Terry DJ, Hogg MA, editors. Attitudes, behavior and social context: The role of norms and group membership. Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Mounts NS, Steinberg L. An Ecological Analysis of Peer Influence on Adolescent Grade-Point Average and Drug-Use. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:915–922. [Google Scholar]

- Nichter M, Nichter M, Vuckovic N, Quintero G, Ritenbaugh C. Smoking experimentation and initiation among adolescent girls: qualitative and quantitative findings. Tobacco Control. 1997;6:285–295. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.4.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Loughlin J, Paradis G, Renaud L, Gomez LS. One-year predictors of smoking initiation and of continued smoking among elementary schoolchildren in multiethnic, low-income, inner-city neighbourhoods. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:268–275. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.3.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetting ER, Donnermeyer JF. Primary socialization theory: The etiology of drug use and deviance. I. Substance Use & Misuse. 1998;33:995–1026. doi: 10.3109/10826089809056252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Gilpin EA. A Historical-Analysis of Tobacco Marketing and the Uptake of Smoking by Youth in the United-States - 1890–1977. Health Psychology. 1995;14:500–508. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.6.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plickert G, Cote RR, Wellman B. It's not who you know, it's how you know them: Who exchanges what with whom? Social Networks. 2007;29:405–429. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LA, Dalton WT, Nicholson LM. Changes in adolescents' sources of cigarettes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:861–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson LA, Murray DM, Alfano CM, Zbikowski SM, Blitstein JL, Klesges RC. Ethnic differences in predictors of adolescent smoking onset and escalation: A longitudinal study from 7th to 12th grade. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:297–307. doi: 10.1080/14622200500490250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D, Romer D, Audrain-McGovern J. Beliefs about the risks of smoking mediate the relationship between exposure to smoking and smoking. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69:106–113. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802e0f0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield PE, Pattison PE, Hill DJ, Borland R. Youth culture and smoking: Integrating social group processes and individual cognitive processes in a model of health-related behaviours. Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8:291–306. doi: 10.1177/13591053030083001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J. Social network analysis: A handbook. London: Saga Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B. Social influences adolescent substance use. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31:672–684. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.6.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Chen R. Latent growth curve analyses of parent influences on drinking progression among early adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:5–13. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Chen R, Abroms L, Haynie DL. Latent growth curve analyses of peer and parent influences on smoking progression among early adolescents. Health Psychology. 2004;23:612–621. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Chen RS. Over time relationships between early adolescent and peer substance use. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1211–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Haynie D. Center for Child Well-being. Growing up drug free: A developmental challenge. In: Bornstein MH, Davidson L, Keyes CLM, Moore KA, editors. Well-being: Positive Development Across the Life Course. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003a. pp. 109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Haynie DL, Crump AD, Eitel P, Saylor KE. Peer and parent influences on smoking and drinking among early adolescents. Health Education & Behavior. 2001;28:95–107. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG. The protective effect of parental expectations against early adolescent smoking initiation. Health Education Research. 2004;19:561–569. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Haynie DL. Psychosocial predictors of increased smoking stage among sixth graders. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003b;27:592–602. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.6.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton Bruce G. Prospective analysis of peer and parent influences on smoking initiation among early adolescents. Prevention Science. 2002;3:275–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1020876625045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smet B, Maes L, De Clercq L, Haryanti K, Winarno RD. Determinants of smoking behaviour among adolescents in Semarang, Indonesia. Tobacco Control. 1999;8:186–191. doi: 10.1136/tc.8.2.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman R, van den Eijnden RJJM, Engels RCME. Self-comparison processes, prototypes, and smoking onset among early adolescents. Preventive Medicine. 2005;40:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton WR, Lowe JB, Gillespie AM. Adolescents' experiences of smoking cessation. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;43:63–70. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)84351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Monahan KC. Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1531–1543. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Bogt TFM, Engels RCME, Dubas JS. Party people: Personality and MDMA use of house party visitors. Addictive Behaviors. 2006;31:1240–1244. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry Deborah J, Hogg Michael A. Attitudes, behaviors, and social context: The role of norms and group membership. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Terry Deborah J, Hogg Michael A, White Katherine M. Attitude-behavior relations: Social identity and group membership. In: Terry Deborah J, Hogg Michael A., editors. Attitudes, behavior and social context: The role of norms and group membership. Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Klein DJ, Elliott MN. Social control of health behaviors: a comparison of young, middle-aged, and older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences. 2004;59B:147–150. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.4.p147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Martinez JF, Ellickson PL, Edelen MO. Temporal associations of cigarette smoking with social influences, academic performance, and delinquency: A four-wave longitudinal study from ages 13 to 23. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:1–11. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyas SL, Pederson LL. Psychosocial factors related to adolescent smoking: a critical review of the literature. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:409–420. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S.Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: Understanding and improving health. Washington, DC: US: Government printing office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Pilgrim C. Close friend and group influence on adolescent cigarette smoking and alcohol use. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:834–844. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Degirmencioglu SM, Tolson JM. Adolescent friendship selection and termination: the role of similarity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1998;15:703–710. [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Luo Q, Pilgrim C, Degirmencioglu SM. A two-stage model of peer influence in adolescent substance use: individual and relationship-specific differences in susceptibility to influence. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1243–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00256-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urberg KA, Shyu SJ, Liang J. Peer Influence in Adolescent Cigarette-Smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 1990;15:247–255. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW. Network models of the diffusion of innovations. Cresskill, NH: Hampton Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Gallaher P, Mouttapa M. Using social networks to understand and prevent substance use: A transdisciplinary perspective. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39:1685–1712. doi: 10.1081/ja-200033210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkooijen KT, de Vries NK, Nielsen GA. Youth crowds and substance use: The impact of perceived group norm and multiple group identification. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:55–61. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Wanner B, Brendgen M, Gosselin C, Gendreau PL. Differential contribution of parents and friends to smoking trajectories during adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster Cynthia M, Freeman Linton C, Aufdemberg Christa G. The Impact of Social Context on Interaction Patterns. Journal of social structure. 2001:2. [Google Scholar]