Abstract

The Xylella fastidiosa comparative genomic database is a scientific resource with the aim to provide a user-friendly interface for accessing high-quality manually curated genomic annotation and comparative sequence analysis, as well as for identifying and mapping prophage-like elements, a marked feature of Xylella genomes. Here we describe a database and tools for exploring the biology of this important plant pathogen. The hallmarks of this database are the high quality genomic annotation, the functional and comparative genomic analysis and the identification and mapping of prophage-like elements. It is available from web site http://www.xylella.lncc.br.

Keywords: genome annotation and assembly, comparative genomics, mobile genetic elements

The quality of bacterial-genome annotation varies. The lack of a direct link between annotation in public databases, and the functional information accumulated over recent years, highlights how the importance of maintaining this up-to-date is becoming a crucial task in the genomics era (Parkhill et al., 2010). Although considerable literature has accumulated on Xylella fastidiosa over the last decade, this information has not been transferred to the annotation files in public databases. Xylella is a phytopathogenic bacterium that causes economically devastating losses in the yields of such crops as grapes, citrus fruits, almonds and other plant species (Van Sluys et al., 2002). The 9a5c strain, the causal agent of citrus variegated chlorosis, was the first bacterial plant pathogen to have its genome completely sequenced (Simpson et al., 2000). Nowadays, besides the six different genomes published, additional strains are part of ongoing sequencing projects.

Genomic studies have indicated extensive lateral gene transfer (LGT) related to prophage-like regions, which in turn are related to intra-genomic deletions, insertions and rearrangements (Monteiro-Vitorello et al., 2005; da Silva et al., 2007). Moreover, the presence of phage particles has also been demonstrated by both electron microscopy (Chen and Civerolo, 2008), and plaque propagation (Summer et al., 2010), all of which implying that phages are capable of playing a major role in genomic shaping and differentiation in Xylella strains (de Mello Varani et al., 2008).

Analysis of the genomic differences between closely related strains provides, not only a starting point towards understand functional and evolutionary processes, but also clues towards defining what makes one strain more pathogenic and/or aggressive than others. This information would be useful in epidemiological studies, all of which can potentially lead to the development of novel disease management strategies by identifying potential gene targets for mitigating infection and/or disease development.

We hereby report the first comprehensive and specialized up-to-date database comprising all the sequenced genomes of the different Xylella fastidiosa strains. The web-accessible application was developed, by using the SABIA package (System for Automated Bacterial Integrated Annotation), a public-domain software for the automated identification of genome landmarks that uses a user-friendly interface for browsing and retrieving data and information (Almeida et al., 2004).

Xylella fastidiosa strains were recently grouped into subspecies (Schaad et al., 2004, 2009), although the current database version follows the original strain identification. The database includes four complete and finished public genomic sequences of strains that cause citrus variegated chlorosis (9a5c), Pierce’s disease (Temecula1), almond leaf scorch and Pierce’s diseases (M23), and almond leaf scorch disease (M12). In addition, the public draft genomes of the strains associated with oleander leaf scorch (Ann1) and almond leaf scorch (Dixon) were assembled (closed but not finished) into candidate molecules representing the main replicon and plasmids. Additional information for finishing and gap-closures can be found in the supplementary material.

Prophage-like element identification was carried out using the methodology implemented by de Mello Varani et al. (2008). Orthologous clusters were identified using the bidirectional best-hit method (Overbeek et al., 1999). This database provides access to the latest annotations that can be downloaded in raw datasets, such as flat file and GenBank file format.

The high-quality annotation process was a collaborative effort among annotator specialists. The database can be searched by gene or protein names, as well as other functional annotation terms. The search engine is capable of further refining queries using SQL rules defined by the user. Nucleotide and amino acid sequences can be searched by BLAST (Altschul et al., 1997).

A genome viewer provides a graphical overview of the position of a given selected gene on the chromosome, as well as of neighboring genes. The annotation integrates information on putative gene products, transcription regulatory sequences and ribosome binding sites. InterPro protein signatures, UniProt (Universal Protein Resource) and the NCBI non-redundant protein database were used with the BLAST program for orthology and similarity assignment. Putative protein localization is assigned by PSORT (Nakai and Horton, 1999), and possible membrane transport capacity using the TCDB database. The Enzyme Commission number (EC Number), Gene Ontology terms and COG phylogenetic classification, were used for functional categorization of the putative gene products. KEGG metabolic pathways are also available through tables and in a graphical overview interface, thereby facilitating user visualization and comparison of the complete set of pathways available in each strain.

All identified prophage-like elements and prophage remnants were characterized and annotated as special features in each strain. They are indicated with a special tag after the gene name, i.e. [phage-related protein, xfp3], where ‘xfp3’ represents the prophage-like element number three of the 9a5c strain. For other strains, the notation is as follows: xpd 1 to 9 for Temecula1, xap 1 to 11 for Dixon, xop 1 to 10 for Ann1, xmp 1 to 9 for M23, and xp 1 to 7 for M12 strains (for details see “Genome sequence alignment and comparative map of prophage regions of the six strains” in Supplementary Materials of the Xylella fastidiosa comparative database, http://www.xylella.lncc.br/supplementary.html).

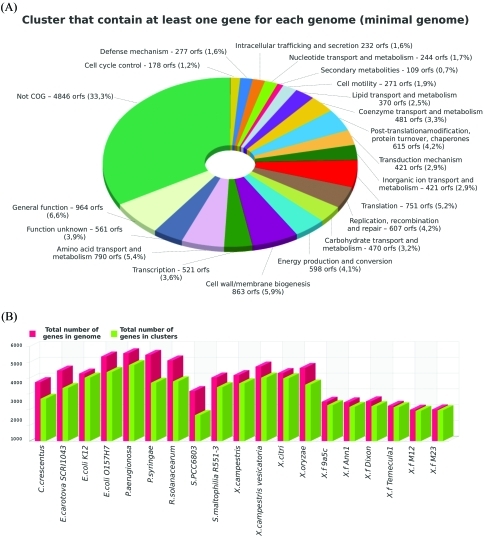

The comparative interface consists of a pre-calculated similarity analysis of Xylella predicted genes against thirteen completely sequenced Proteobacteria genomes, by using reciprocal BLAST searches for the computation of BBH clusters (Table 1). The core and pan genome calculation was estimated, and can be accessed as tables and graphs (Figure 1). Proteins involved in a common structural complex or metabolic pathway are highlighted and this information is associated with the identification of strain-specific regions that might be related to host specificity.

Table 1.

The database includes, other than the genomes of the 6 strains of Xylella, the genomes of species considered as references for comparative analysis.

| Number of genes with products of known function | Number of conserved genes with products of unknown function | Number of hypothetical genes | Total of genes | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | Genome | Cluster | % | Genome | Cluster | % | Genome | Cluster | % | Genome | Cluster | % |

| Caulobacter crescentus | 2198 | 2059 | 93% | 550 | 424 | 77% | 989 | 203 | 20% | 3737 | 2686 | 71% |

| Erwinia carotovora atroseptica SCRI1043 | 3630 | 3250 | 89% | 602 | 441 | 73% | 240 | 7 | 2% | 4472 | 3698 | 82% |

| Escherichia coli K12 | 2927 | 2854 | 97% | 11 | 9 | 81% | 1341 | 1162 | 86% | 4279 | 4025 | 94% |

| Escherichia coli O157H7 | 3461 | 3125 | 90% | 0 | 0 | 0% | 1900 | 1258 | 66% | 5361 | 4383 | 81% |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 3022 | 2922 | 96% | 760 | 734 | 96% | 1785 | 1172 | 65% | 5567 | 4828 | 86% |

| Pseudomonas syringae | 3917 | 3676 | 93% | 944 | 769 | 81% | 610 | 27 | 4% | 5471 | 4472 | 81% |

| R. solanacearum | 3601 | 3081 | 85% | 670 | 509 | 75% | 845 | 199 | 23% | 5116 | 3789 | 74% |

| S. maltophilia R551-3 | 3129 | 2943 | 94% | 510 | 409 | 80% | 393 | 69 | 17% | 4032 | 3421 | 84% |

| S. maltophilia PCC6803 | 2737 | 1370 | 50% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 429 | 279 | 65% | 3167 | 1650 | 52% |

| Xanthomonas campestris | 2691 | 2467 | 91% | 1 | 1 | 100% | 1489 | 1194 | 80% | 4181 | 3662 | 87% |

| Xanthomonas campestris vesicatoria | 2689 | 2462 | 91% | 5 | 2 | 40% | 2032 | 1561 | 76% | 4726 | 4025 | 85% |

| Xanthomonas citri | 2705 | 2639 | 97% | 1276 | 1230 | 96% | 331 | 112 | 33% | 4312 | 3981 | 92% |

| Xanthomonas oryzae | 3281 | 2561 | 78% | 24 | 19 | 79% | 1332 | 1001 | 75% | 4637 | 3581 | 77% |

| X.f. 9a5c (CVC) | 1702 | 1658 | 97% | 351 | 330 | 94% | 439 | 289 | 65% | 2492 | 2277 | 91% |

| X.f. Ann1 (OLS) | 1686 | 1587 | 94% | 339 | 292 | 86% | 432 | 288 | 66% | 2457 | 2167 | 88% |

| X.f. Dixon (ALS) | 1793 | 1617 | 90% | 294 | 283 | 96% | 434 | 311 | 71% | 2521 | 2211 | 87% |

| X.f. M12 (ALS) | 1496 | 1474 | 98% | 275 | 269 | 97% | 218 | 178 | 81% | 1989 | 1921 | 96% |

| X.f. M23 (ALS/PD) | 1535 | 1529 | 99% | 263 | 260 | 98% | 209 | 170 | 81% | 2007 | 1959 | 97% |

| X.f. Temecula1 (PD) | 1576 | 1549 | 98% | 292 | 284 | 97% | 370 | 309 | 83% | 2238 | 2142 | 95% |

Figure 1.

Distribution of the core and pan genome of all the strains in the database can be accessed. (A) Functional categorization of genes that are shared by at least two genomes; (B) Total number of genes vs. total number of genes in clusters for each genome within the database.

The database attempts to provide a comprehensive view of all sequence elements and their related functions in Xylella genomes, providing a valuable online resource for Xylella community researchers. Expectedly, its use will contribute to understanding the biology of Xylella, and to the study of the mechanisms involved in its pathogenicity. New sequenced Xylella genomes can be included in future versions of the database, after the complete annotation and curation process.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anamaria Aranha Camargo, Alexandre Morais do Amaral, Sergio Verjovski-Almeida, Luis Eduardo Aranha Camargo, Carlos F.M. Menck, Marilis do Valle Marques, Eliana Macedo Lemos, Manoel Vitor Lemos, Ana Lucia Nascimento, Mariana C. de Oliveira and Marcelo Zerillo for assistance in the re-annotation process, and Roger Paixão for extensive bioinformatics support. This work was supported by FAPESP (São Paulo, SP, Brazil) and CAPES/CNPq (Brasília, DF, Brazil) and USDA-ARS.

References

- Almeida LG, Paixão R, Souza RC, Costa GC, Barrientos FJ, Santos MT, Almeida DF, Vasconcelos AT. A System for Automated Bacterial (genome) Integrated Annotation SABIA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2832–2833. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Civerolo EL. Morphological evidence for phages in Xylella fastidiosa. Virol J. 2008;6:75. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva VS, Shida CS, Rodrigues FB, Ribeiro DC, de Souza AA, Coletta-Filho HD, Machado MA, Nunes LR, de Oliveira RC. Comparative genomic characterization of citrus-associated Xylella fastidiosa strains. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:e474. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Mello Varani A, Souza RC, Nakaya HI, de Lima WC, Paula de Almeida LG, Kitajima EW, Chen J, Civerolo E, Vasconcelos AT, Van Sluys MA. Origins of the Xylella fastidiosa prophage-like regions and their impact in genome differentiation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e4059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro-Vitorello CB, de Oliveira MC, Zerillo MM, Varani AM, Civerolo E, Van Sluys MA. Xylella and Xanthomonas Mobil’omics. OMICS. 2005;9:146–159. doi: 10.1089/omi.2005.9.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai K, Horton P. PSORT: A program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:34–36. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeek R, Fonstein M, D’Souza M, Pusch GD, Maltsev N. The use of gene clusters to infer functional coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2896–2901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J, Birney E, Kersey P. Genomic information infrastructure after the deluge. Genome Biol. 2010;11:e402. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-7-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaad NW, Postnikova E, Lacy G, Fatmi M, Chang CJ. Xylella fastidiosa subspecies: X. fastidiosa subsp piercei, subsp. nov., X. fastidiosa subsp. multiplex subsp. nov., and X. fastidiosa subsp. pauca subsp. nov. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2004;27:290–300. doi: 10.1078/0723-2020-00263. Erratum in Syst Appl Microbiol 27:763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson AJ, Reinach FC, Arruda P, Abreu FA, Acencio M, Alvarenga R, Alves LM, Araya JE, Baia GS, Baptista CS, et al. The genome sequence of the plant pathogen Xylella fastidiosa. Nature. 2000;406:151–159. doi: 10.1038/35018003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summer EJ, Enderle CJ, Ahern SJ, Gill JJ, Torres CP, Appel DN, Black MC, Young R, Gonzalez CF. Genomic and biological analysis of phage Xfas53 and related prophages of Xylella fastidiosa. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:179–190. doi: 10.1128/JB.01174-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sluys MA, de Oliveira MC, Monteiro-Vitorello CB, Miyaki CY, Furlan LR, Camargo LE, da Silva AC, Moon DH, Takita MA, Lemos EG, et al. Comparative analyses of the complete genome sequences of Pierce’s disease and citrus variegated chlorosis strains of Xylella fastidiosa. J Bacteriol. 2002;185:1018–1026. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.1018-1026.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- InterPro protein sequence analysis & classification. [August 10, 2011]. http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro.

- KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. [August 10, 2011]. http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg.

- The Gene Ontology. [August 10, 2011]. http://www.geneontology.org.

- Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs) [August 10, 2011]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG.

- Prediction of Protein Sorting Signals and Localization Sites in Amino Acid Sequences (PSORT) [August 10, 2011]. http://psort.hgc.jp.

- Functional and Phylogenetic Classification of Membrane Transport Proteins (TCDB) [August 10, 2011]. http://www.tcdb.org.

- Universal Protein Resource (UNIPROT) [August 10, 2011]. http://www.uniprot.org.