Abstract

Background

Implementing improvement programs to enhance quality of care within primary care clinics is complex, with limited practical guidance available to help practices during the process. Understanding how improvement strategies can be implemented in primary care is timely given the recent national movement towards transforming primary care into patient-centered medical homes (PCMH). This study examined practice members’ perceptions of the opportunities and challenges associated with implementing changes in their practice.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of 56 individuals working in 16 small, community-based primary care practices. The interview consisted of open-ended questions focused on participants’ perceptions of: (1) practice vision, (2) perceived need for practice improvement, and (3) barriers that hinder practice improvement. The interviews were conducted at the participating clinics and were tape-recorded, transcribed, and content analyzed.

Results

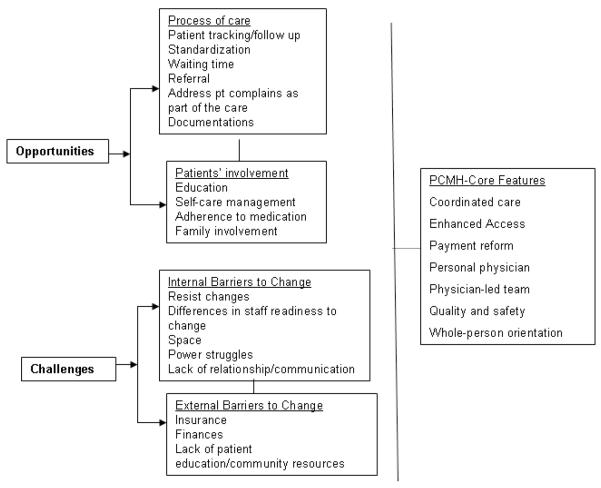

Content analysis identified two main domains for practice improvement related to: (1) the process of care, and (2) patients’ involvement in their disease management. Examples of desired process of care changes included improvement in patient tracking/follow-up system, standardization of processes of care, and overall clinic documentations. Changes related to the patients’ involvement in their care included improving (a) health education, and (b) self care management. Among the internal barriers were: staff readiness for change, poor communication, and relationship difficulties among team members. External barriers were: insurance regulations, finances and patient health literacy.

Practice Implications

Transforming their practices to more patient-centered models of care will be a priority for primary care providers. Identifying opportunities and challenges associated with implementing change is critical for successful improvement programs. Successful strategy for enhancing the adoption and uptake of PCMH elements should leverage areas of concordance between practice members’ perceived needs and planned improvement efforts.

Keywords: primary care practice, quality improvement, qualitative analysis

Introduction

‘Change is not made without inconvenience, even from worse to better.’

Richard Hooker, 1554–1600

Practice improvement or redesign refers to intentional efforts to improve practice processes and outcomes1. Implementing such transformation within primary care settings is complex, in spite of the availability of clear practical guidance to help small clinical practices during the process2. For example, The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) has developed and adapted tools to help organizations accelerate improvement (http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Tools/default.aspx). However, a critical gap continues to exist in the uptake and adoption of best practices and evidence-based medicine3. To address this gap, several studies have been conducted across a broad range of settings to conceptualize improvement in primary care practice 4-9. Findings from these studies suggest that guiding principles for a sustainable change include clear understanding of practices’ vision and mission, enhanced learning and reflection and diverse perspectives to foster adaptability and uptake.

Cohen et al10, highlighted the potential role of several complex interactions of internal and external factors on implementing improvement strategies. They identified practice characteristics such as the individual and aggregate motivations of practice members, the resources that members recognize within and outside the practice, the external forces that shape improvement options, and practice members’ perception of opportunities for improvement. Similarly, other studies suggested that transforming primary care practices depends upon a number of factors including time, financial support, payment reform, health policy support, and physician support11-12. These factors are all highly interconnected and impact a practice’s ability to implement suitable and sustainable improvement13.

Understanding practice improvement process is especially important with the recent national efforts to implement The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) 14. The PCMH model is a patient-driven, team-based approach that delivers efficient, comprehensive and continuous care through active communication and coordination of healthcare services11-15, Table 1]. Studies on the implementation and uptake of the PCMH model in primary care setting are limited. Emerging evidence suggests that larger organization size is associated with greater presence of PCMH features, but even among large groups, adoption of core PCMH features is low14,16. To close the gap in our understanding of how primary care clinics implement re-design efforts, it is important to examine and understand contextual factors that influence the implementation of new procedures in real world settings6,17. Exploring these factors further and testing their association with changes in health care delivery will provide insights that foster implementation of new models of primary care.

Table 1.

Core features of The Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH)

| Core Features | Definition |

|---|---|

| Coordinated care | Care that is facilitated through information exchange across the health care system. |

| Enhanced Access | Care that is available via expanded hours and open communication between health care employees and patients. |

| Payment reform | A payment structure that supports coordination of care, use and implementation of new technologies, and enhanced access. |

| Personal physician | Individualized, continuous, and comprehensive patient care emphasized and overseen via a personal physician. |

| Physician-led team | Physician-led medical teams that collectively take responsibility in caring for patients. |

| Quality and safety | Partnerships between physicians and patients that include active patient decision-making, self-care management, evidence-based medicine, and quality improvement activities. |

| Whole-person orientation |

Care overseen by a personal physician and coordinates acute care, chronic care, preventative services, and end-of-life care |

Primary care practices are clinical microsystems, or small organized units with a specific clinical purpose, set of patients, technologies, and practitioners who work directly with these patients. Clinical microsystems are themselves Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS), comprised of individuals who learn, inter-relate, and self-organize to complete tasks. They also co-evolve with their environment, responding to internal and external forces in ways that in turn reshape their external environment. A CAS is characterized by non-linear interactions that lead to outputs, or “emergent” properties, that are not totally expected18-21. Here we approach understanding primary care clinic redesign from a CAS approach.

Conceptualizing improvement in primary care using CAS theory has important implications. A CAS perspective emphasizes the importance of context and organizational history, as each clinical microsystem has had experienced a unique trajectory of development and organization within its environment. Recognizing this context and environment has important implications for success22. Additionally, the CAS framework stresses the importance of relationships and interdependencies among individuals. These relationships and non-linear interdependencies among practice members can either enhance or inhibit sense-making and learning as members of the practice team attempt to implement change23, 24. Thus, the ability of practices to improve will be greatly influenced by the relationships among individuals in the clinic20. By focusing on multiple interactions, history and context rather than on single cause-effect mechanisms, a CAS approach to practice re-designs supports development of tailored interventions. Identifying essential functional tasks or processes and monitoring their implementation offers a means of assessing intervention fidelity, recreating programs successfully in other settings, and in understanding conditions under which positive deviance or desirable variation arises21.

In this paper, we report practice members’ perception of opportunities and challenges to implementing improvement strategies from a study to improve care delivery and chronic disease outcomes, in small autonomous primary care practices. Using the CAS framework, we focus on issues related to context and relationships, and their potential influence on practice improvement efforts. This work is timely given the recent national movements towards transforming primary care practices towards a medical home model which will require significant practice improvement.

Methods

Participants in this study were staff and clinicians working in small autonomous primary care clinics. All participants were enrolled in a group randomized study of primary care practices (Internal Medicine and Family Medicine) in San Antonio and the surrounding areas. The study design and background have been previously reported25. Briefly, the ABC study was a randomized trial with a delayed intervention group whose aim was to improve outcomes of diabetes care by using CAS principles to help practices better implement elements of the Chronic Care Model using a Practice Facilitator who functioned as an external facilitator to assist practices with change efforts.

As part of the baseline evaluation of each clinic before the facilitation intervention, we conducted direct observations at the participating clinics and semi-structured interviews with the clinic providers and staff. The Practice Observations Form was used to notate information on (1) clinic location/environment [e.g., physical address, office setting, space], and (2) office operations [e.g., computer use, billing, & medical records]. Semi structured interviews elicited clinic members’ perception on their practice vision and the kinds of improvements they would like to make to improve the quality of care for patients with chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes) during the study.

Semi-structured Interview Development

A panel of experts in practice improvement and health services research created a series of open-ended questions regarding practice improvement. The initial questions were guided by concepts derived from CAS approach and included a special focus on practice members’ communications, relationship and learning. This panel consisted of professionals with multidisciplinary experience including an anthropologist, health service scientist, psychologist, family physicians, and statistician. The revised questions were pretested with practice members [n=5] working in three different clinics to evaluate the questions for clarity and to identify any additional themes not addressed by the initial questions. These themes were then used to develop additional questions and finalize the guide for the semi-structured interview.

Semi-Structured Interview Administration

A purposive sample of providers and staff in 16 clinics were interviewed [n=56] to elicit a variety of responses about members’ perception of opportunities and challenges for improvement. Interview participants included both clinical staff and administrative staff to provide different perspectives, prevent sampling bias, and identify possible discordance. Each clinic included an interview with at least one physician, one back office staff and one front office staff members. The semi-structured interviews elicited information on practice setting, leadership and practice characteristics. The interview consisted of open-ended questions that focused on three main domains. These domains included practice members’ perception of: (1) practice vision, (2) needs for practice improvement, and (3) barriers that hinder practice improvement “see table 1 for PCMH definitions”. Some selected examples of the open-ended questions are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Selected example of open-ended questions related to practice change.

| Theme | Open-ended question |

|---|---|

| Practice vision/goals | What are this clinic’s goals, values or mission? How does this clinic differ from other clinics you’ve worked in previously? How the clinic staff (i.e., physicians, nurse practitioners or physician assistants, medical assistants, receptionists) share this vision, what do they do to achieve clinic’s goals? |

| Needs Assessment at the Clinics |

How do you assess your clinic’ needs for change? What have you as a clinic tried to change in the past? Was it successful? Why or why not? Can you tell me about a recent change in this clinic such as hiring a new staff member, changing your medical records in some way or the patient appointment system or staff responsibilities? |

| Changes hope to make | Are there any changes that you have thought about or that you and the staff have met about that might improve the health of your patients, why? Do you have any idea on how this will happen or who will make it happen? |

| Facilitators to practice change | Probe: How did the clinic deal with this event (s)? Did the ways in which staff related to each other/interact with each other change? If so, how did they change? How did staff in the practice figure out how to handle the new situation? What happened afterwards? What facilitated your changes? |

| Barriers to practice change | Changing the way a clinic like this operates is often difficult. Probe: Are there specific in internal barriers to changes that effect how patients are seen in this clinic (i.e., specific factors with the physicians or clinicians that make change difficult or specific factors with the clinic staff that make change difficult)? Are there external barriers that make change difficult (i.e., regulations, insurance, hospital system, other clinic)? |

Considerable flexibility during the interviews allowed participants to discuss issues that were most important to them. The semi-structured interviews lasted for about one hour and were all conducted by a person experienced in qualitative techniques in order to avoid leading questions and biased answers. The semi-structured interviews were conducted at the clinics where participants worked, and were tape-recorded, transcribed, and content analyzed. We used the software NVIVO to perform the content analysis. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio approved the study protocol. All participants signed a copy of the informed consent form.

Data Analysis

Content analysis was performed on the transcriptions of the semi-structured interviews. Based on participants’ responses regarding practice improvement, we constructed and defined a series of temporary categories and established a filing and retrieval system for these categories. An integrated approach26,27 to qualitative data analysis was used that incorporated both inductive and deductive codes. Initial deductive codes were developed using empiric sources from the literature about practice improvement and CAS approach. Examples of these codes are practice members’ relationship and communication and the inter dependencies among members in the practice. Inductive codes were based on responses (free or semi-guided) provided by participants during the semi-structured interviews. Examples of these codes are internal and external barriers to improvement, and patients’ health education.

Content analysis was conducted in three steps. First, for each subject, we built an initial matrix that consisted of cells presenting staff and providers’ responses extracted from the interviews. The text of these cells was either direct quotations or summations of responses. Second, we examined the initial matrices in order to identify patterns across the 56 cases. Patterns recognized in this analysis formed the basis of additional categorization to construct higher-level matrices. These higher-level matrices were summarized into tables representing participants’ responses. All matrices were checked and evaluated to assure consistency in coding and classification procedures. The analysis was primarily conducted by one experienced researcher in qualitative methods, while another research staff member independently examined 50% of the materials (e.g., transcripts, initial matrices) to confirm the integrity of the emerging themes and concepts. Inter-coder reliability was assured through a coding comparison method by another research staff. Once development of the coding tree was advanced, the researchers and the assistants involved in this project recoded 20% of the transcribed materials selected at random. Agreement was acceptable (Kappa Coefficients=0.75). An iterative process was used in the analysis to revise and refine all emerged patterns regarding practice improvement. The presentation of qualitative results and themes from interviews is reflected in terms of frequency and percentage. We used this approach not to generalize our findings but to reflect the occurrence of the identified themes across cases.

Results

Overall description of the clinics

Sixteen clinics who participated in the ABC Intervention Study were included in this analysis. A total of 56 (3-4 per clinic) individuals were interviewed, including physicians (n=16), nurses and staff members (n=40). The majority (11, 68%) of the enrolled clinics were located in a commercial/medical setting in San Antonio, TX. Ten clinics (62%) used software to organize patient scheduling, while six clinics (38%) used handwritten paper-based files and 57% of clinics used Electronic Medical Record (EMR). About 14 (88%) of the participating clinics handled patient inquires by the front office staff and all clinics had an answering machine to record messages. Most of the clinics (15, 94%) allowed patients’ walk-in patient scheduling.

Opportunities and Challenges Associated with Implementing Practice Improvement

In the following section, we report on our findings regarding practice members’ perceptions of opportunities and challenges associated with implementing practice improvement. The findings describe practice members’ responses to their practice vision, perceived needs and barriers to practice improvement.

Clinic Vision

In general, staff and providers described the office setting as a “family” like environment. A total of 43 individuals of the 56 provided information about their perception of their clinic’s practice vision representing the final analytical study sample [see Table 3]. All respondents who commented on practice vision indicated that the clinic staff and providers share a similar vision of what is important to their respective practice. The majority (36, 84%) from 14 clinics reported that patient care and patient satisfaction were central components/features of their main vision. One nurse indicated: “Patients come first. That’s all there is to it.”, while another physician similarly stated: “The most important thing is improving patient care. That is the bottom line”. While in general most respondents described their office setting as a “family” like environment/atmosphere, six individuals (11%) from 5 clinics specifically expressed that this concept and patient care/satisfaction was central to their practice vision. Only one person indicated that the most important goal of the practice is making money.

Table 3.

Staff and providers responses to practice vision [n=16 clinics]

| Individuals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percent (%) | |

| Practice Vision (n=43) | ||

| Patient Care/Satisfaction | 36 | 84% |

| Patient Care & Family Environment | 6 | 14% |

| Making Money | 1 | 2% |

|

| ||

| Totals | 43 | 100% |

|

| ||

| Change hope to make: (n=38) | ||

| Processes of care domain | ||

| Patient tracking/follow up | 6 | 16 |

| Standardization/waiting time | 5 | 12 |

| Referral | 1 | 3 |

| Pt complains | 1 | 3 |

| Documentations | 1 | 3 |

| Patients domain | ||

| Education | 11 | 29 |

| Self-care management | 9 | 24 |

| Adherence to medication | 3 | 7 |

| Family involvement | 1 | 3 |

|

| ||

| Totals | 38 | 100% |

Perceived needs for practice improvement

Staff and clinicians (n=38) reflected on what they like to improve in their clinic. Content analysis identified two main domains: (1) improvements related to the process of care and (2) improvements related to patients’ involvement in their care [Table 3]. The most common suggestion pertaining to the process of care was improvements in patient tracking/follow up systems (6, 16%). Several other individuals mentioned improvements in standardizing processes of care and reducing waiting time for patients in the clinic (5, 12%), along with comments regarding improving patients’ referral processes (1, 3%), responding to patients’ complaints (1, 3%) and improving overall clinic documentations (1, 3%). One physician stated: “…something about the flow of patients and the waiting time, how they feel about that. What things are you going to track down to prove at the end that whatever recommendations we need, right. So it’s something at the end we can look at it and find it productive, not only for the study but for myself”.

Desired improvements related to the patients’ domain most noticeably included recognizing challenges pertaining to improvement in patient health education and activation around self-care activities (11, 29%). One nurse said: “Like for the newly diagnosed diabetics. We send them over to a class at Methodist [Hospital]. I don’t have time. That’s like a job in itself. You need a teaching nurse for that”. Other improvements were related to improve patients’ self-care management (9, 24%). A physician commented: “I think a lot of diabetics are in denial. As long as they stay off insulin, they don’t think taking care of the other factors, like their diet, staying compliant with their meds, or exercising is all that important. So they just let things slide”.

Participants also perceived a need to improve patients’ adherence to medication (3, 7%), one medical assistant said: “And it’s like I can’t be doing that. When I ask you to come in, I need you to come in; when I ask you to take certain insulin or a certain pill I need you to do that”. Only one person (3%) perceived a need to engage family members in patients’ disease management (1, 3%).

Staff and clinicians reflected on how their practices identified needs (or priorities for improvement), how improvement plans are implemented, and how staff responds to improvement within their respective clinic. More than half of participants (32, 57%) from 11 clinics stated that staff members were expected to identify problems and implement improvement by working together as a group to find a common solution. One physician stated: “The move over here was really as painless as a move such as ours could be and it was all because of my fantastic staff and how they volunteered their time to work on the weekend to get the move done”. Fifteen (27%) of the respondents from 6 clinics stated that improvement is assessed and supervised by management. A medical transcriptionist reported on how improvement is overseen by management, she stated: “Dr. X is working to get paper chart information completely into the electronic database…but we’re still waiting”. Only nine (16%) individuals from 11 clinics stated that improvements were assessed and implemented in a silo with no coordination. For example, a receptionist in clinic C described how her new management is not effective in organizing processes related to work flow, she stated: “like with their times [old manager], one of us would open and one of us would close. The next week we rotate, whoever was closing that week, would open the next week, so we’d switch like that. With him, we’re just like-all over the place. No order”.

When asked about prior experiences with change efforts in the clinic, 36 of all 56 participants (64%) from 15 clinics stated that their response to improvement was positive. However, 9 (17%) from 4 clinics stated that their response was neutral while 11 individuals (19.2%) from 6 clinics perceived that their response to improvement was negative.

Barriers to Improvement

Of the 40 participants who identified internal barriers to implementing improvement in their clinic, 15 individuals (38%) from 9 clinics noted differences among the staff in their clinic in accepting improvement (see Table 4). For instance, a medical assistant stated: “you know she likes things done a certain way, and that will you know and improvement means that you have to work on another way of doing it and you have to be comfortable with that…some people aren’t comfortable even if it’s at the right way”.

Table 4.

Participants’ perception on change in the Clinic [n=16 clinics]

| Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Identifying/Implementing Problems (n=56) | ||

| Staff members identify/implement change by working together |

32 | 57% |

| Change overseen by management | 15 | 16% |

| Silo | 9 | 16% |

| Total | 56 | |

|

| ||

| Response (n=56) | ||

| Positive | 36 | 64.2% |

| Neutral | 9 | 16.6% |

| Negative | 11 | 19.2% |

| Total | 56 | |

|

| ||

| Internal Barriers to Change (n=40) | ||

| Resist changes | 15 | 37.5% |

| Differences in staff readiness to change | 13 | 32% |

| Space | 5 | 12.5% |

| Power struggles | 4 | 10.5% |

| Lack of relationship/communication | 3 | 7.5% |

| Total | 40 | |

|

| ||

| External Barriers to Change (n=39) | ||

| Insurance | 17 | 44% |

| Finances | 14 | 36% |

| Lack of patient education | 8 | 20% |

| Total | 39 | |

Another internal barrier stated by 13 (32%) individuals in 7 clinics was personality clashes and lack of relationships among team members. One receptionist said: “When it’s a new person coming in and they don’t know our personalities and we really don’t know their personalities, there are a lot of people that can’t take it”. A third internal barrier identified by three individuals (8%) in 3 clinics was lack of relationship. One nurse said, “Yeah, some people get along very well and they can work better than others. I mean we have even staff---there’s some staff in other offices that [x] cannot stand, cannot work together with. She doesn’t tell me that, but I can tell”. Additional internal barriers included power struggles (4, 11%) among clinic members. One nurse indicated: “He has this really male chauvinist attitude…and he still wants to have the majority of the control [of the practice] over [the owners].” Lack of space was also mentioned as a barrier among some clinic members (5, 13%) from 3 clinics.

Additionally, nearly all of the staff and clinician respondents (n=39) identified several specific external barriers to improvement. Nearly half (17, 44%) from 10 clinics stated that insurance regulations represent the main external barrier to improvement, while 14 (36%) from 4 clinics stated that finances were also important 8 (20%) from 9 clinics also perceived patient flow and education as significant external barrier to improvement (Table 4).

Discussion

Understanding clinic member perceptions about the factors that might influence improvement efforts in primary care practice is essential to delivering high quality of care1. In fact, implementing practice re-design change starts with clear and shared vision among practice members to deliver the best care for their patients. Practice vision can become a motivating force behind practice improvement attempts7. In our study, the majority of members identified a clear and shared vision for their practice in alignment with The PCMH. In addition, staff and providers have identified several opportunities and challenges associated with implementing necessary/clinically beneficial improvements strategies in their practice [Figure 1]. Some members reported needs for improvements in coordination of care, such as improvement in patients’ referral processes. Others reported needs for improvement in patient tracking (e.g., follow up system), waiting time for patients in the clinic, and handing patients’ complaints. Interestingly, these identified perceived needs correspond with several important elements of the PCMH and care provided via elements of the Chronic Care Model (CCM), specifically in the domain related to improving processes of care (e.g., improvement in patient tracking) to deliver efficient, comprehensive and continuous care through active communication and coordination of healthcare services11,15. These synergetic findings between practice’s members perceived needs for improvement and some elements of PCMH may enhance practice members uptake and implementation of PCMH [Figure 1]. For instance, Cohen10 showed that interventions that are based on understanding staff perceptions of opportunities for practice improvement can help in quality improvements of primary care practices.

Fig 1.

Opportunities and challenges associated with practice improvement

Similarly, the CAS framework highlights the needs for local adaptation of processes to suit the needs of the practice members involved19. Any successful strategies for improvement should identify, map and leverage areas of concordance between practice members’ perceived needs and the planned interventions [e.g., PCMH]. A tailored approach to practice improvement will not only allow meaningful improvement but also will overcome barriers and ultimately lead to sustainable interventions9. Our findings on opportunities for practice improvement are timely, given the recent national movement towards transforming the primary care environment into settings more reflective of the PCMH model in order to improve health care delivery and quality of care.

Our findings identified several perceived internal and external barriers to implementing improvements in practice [Figure 1]. Likewise, other studies highlighted the potential role of the interactions of internal and external factors on implementing improvement. For example, Cohen et al10 identified practice characteristics such as the individual and aggregate motivations of practice members; the resources that members recognize within and outside the practice; the external forces that shape improvement options; and practice members’ perception of opportunities for improvement. In this study, external barriers were linked to insurance regulations, finances [return on investment] and adequate resources for patient health education and activation around self-care activities. In the same way, other researchers suggested that transforming primary care practices depends upon a number of factors including time, financial support, payment reform, health policy support, and physician support11,12. These factors are all highly interconnected and impact a practice’s ability to implement suitable and sustainable improvement13. Therefore, it is important not to only identify these factors but also examine their interconnectivity and dependency.

Participants in our study identified poor relationships and communication among team members as major internal barriers to implementing improvement. From a CAS perspective this is critical because sense-making and learning that leads to successful practice improvement activities are emergent properties of the relationship infrastructure within the clinic20,24. Investing in collaborative team development of clinicians and staff should enable the practice to be more adaptive as it undertakes and attempts to sustain improvement efforts. There is also some evidence that leadership can enhance the success of practice improvement efforts by creating an environment that fosters trust and allows practice members to feel safe to speak up when they engage in problem-solving activities28.

Our findings illustrated variations in practice teams’ perceptions of opportunities and challenges regarding improvement in their practices. This observation stresses the uniqueness of each practice and suggests that “one size does not fit all”. As primary care practices tend to adopt some or all features of the PCMH, we expect that practices will implement elements that fit their practice’s needs and address barriers to implementation.

Recent evidence from the national TransforMed demonstration project has indicated initial positive results in terms of PCMH implementation success and quality improvements efforts29-32. Successful strategy for enhancing the adoption and uptake of PCMH elements should leverage areas of concordance between practice members’ perceived needs and the planned interventions. However, the real challenge is whether practices can sustain quality improvements efforts within a dynamic, co-evolving healthcare system.

Summary

Overall, several themes related to opportunities for implementing practice improvement strategies based on practice members’ perceptions emerged [Figure 1]. These opportunities include improvements in process of care, and patients’ involvement in their disease management. Additionally, our findings suggest that both internal and external barriers may hinder practice improvement efforts. Identifying these opportunities and challenges has important implications for PCMH initiative and the new healthcare reform measures.

Acknowledgment

The project described was supported by Award Number R18DK075692 from the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute Of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health. The views expressed are those of the investigators and do not necessarily represent the position of the policy of the Department of Veteran Affairs

Funded Sources: NIH-NIDDK

Literature Cited

- 1.Coleman K, Mattke S, Perrault P, Wagner E. Untangling Practice Redesign from Disease Management: How Do We Best Care for the Chronically Ill? Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30:385–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimshaw JM, Thomas RE, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay CR, Vale L, Whitty P, Eccles MP, Matowe L, Shirran L, Wensing M, Dijkstra R, Donaldson C. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(6):1–72. doi: 10.3310/hta8060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Closing the gap between research and practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ. 1998;317:465–468. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, Stange KC. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:369–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simpson D. A conceptual framework for transferring research to practice. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stetler C, Ritchie J, Rycroft-Malone J, Schultz A, Charns M. Improving quality of care through routine, successful implementation of evidence-based practice at the bedside: An organizational case study protocol using the Pettigrew and Whipp model of strategic change. Implement Sci. 2002;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein K, Conn A, Sorra J. Implementing computerized technology: An organizational analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2002;86:811–824. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Litaker D, Tomolo A, Liberatore V, Stange K, Aron D. Using complexity theory to build interventions that improve health care delivery in Primary Care. J Gen Int Med. 2006;21(S2):S30–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solberg LI. Improving medical practice: A conceptual framework. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:251–256. doi: 10.1370/afm.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen D, McDaniel R, Crabtree B, Ruhe M, Weyer S, Tallia A, Miller WL, Goodwin MA, Nutting P, Solberg LI, Zyzanski SJ, Jaén CR, Gilchrist V, Stange KC. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthcare Manag. 2004;49:155–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nutting PA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Initial Lessons From the First National Demonstraction Project on Practice Transformation to a Patient-Centered Medical Home. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:254–60. doi: 10.1370/afm.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rittenhouse DR, Stephen Shortell. The Patient-Centered Medical Home – Will It Stand the Test of Health Reform? JAMA. 2009;301:2038–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, Strange KC. Practice Jazz: Understanding Variation in Family Practices Using Complexity Science. J Fam Pract. 2001;50(10):872–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedberg DG, Anton Kuzel. Elements of the Patient-Centered Medical Home in Family Practices in Virginia. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(4):301–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosser WW, Colwill JM, Kasperski J. Patient-Centered Medical Homes in Ontario. NEJM. 2010;7:1–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rittenhouse DR, Casalino LP, Gillies RR, Shortell SM, Lau B. Measuring the Medical Home Infrastructure in Large Medical Groups. Heath Aff(Millwood) 2008;27(5):1246–58. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, Maglione MA, Roth EA, Grimshaw JM, Mittman BS, Rubenstein LV, Rubenstein LZ, Shekelle PG. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: A meta-analysis. Ann Int Med. 2002;136:641–651. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-9-200205070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR, Jr., Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Stange KC. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Joint Commission J Qual & Patient Safety. 2005;31(8):438–446. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDaniel RR, Jr, Driebe DJ. Complexity Science and Health Care Management. Advances in Health Care Management. 2001;2:11–36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323(7313):625–628. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plsek P. Redesigning Health Care with Insights from the Science of Complex Adaptive Systems. In Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Heath System for the 21st Century. National Academy of Sciences. 2000:309–322. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leykum LK, Pugh JA, Lanham J, Harmon J, McDaniel R. Implementation Research Design: Integrating participatory action research into randomized controlled trials. Implementation Science. 2009;4(69) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jordan Michelle E., Lanham Holly J., Crabtree Benjamin F., Nutting Paul A., Miller William L., Stange Kurt C., McDaniel Reuben R., Jr. The role of conversation in health care interventions: Enabling sensemaking and learning. Implementation Science. 2009;4(15):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lanham Holly J., McDaniel Reuben R., Jr., Crabtree Benjamin F., Miller William L., Stange Kurt, Tallia, Al, Nutting Paul A. How improving practice relationships among clinicians and nonclinicians can improve quality in primary care. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2009;35(9):457–466. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35064-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parchman M, Pugh1 J, Culler S, Noel P, Arar N, Romero R, Palmer R. A Group Randomized Trial of a Complexity-based Organizational Intervention to Improve Risk Factors for Diabetes Complications in Primary Care Settings: Study Protocol. Implementation. 2008:5–00. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernard HR. Research methods in cultural anthropology. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedberg MW, Safran DG, Coltin KL, Dresser M, Schneider EC. Readiness for the Patient-Centered Medical Home: Structural Capabilities of Massachusetts Primary Care Practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):162–169. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0856-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stange KC, Miller WL, Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart BF, Jaén CR. Context for Understanding the National Demonstration Project and the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:S2–8. doi: 10.1370/afm.1110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaén CR, Crabtree BF, Palmer RF, Ferrer RL, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stewart EE, Wood R, Stange KC. Methods for Evaluating Practice Change Toward a Patient-Centered Medical Home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:S9–20. doi: 10.1370/afm.1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Palmer RF, Ferrer RL, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Stewart EE, Wood R, Stange KC, Jaén CR. Effect of Facilitation on Practice Outcomes in the National Demonstration Project Model of the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8:S33–44. doi: 10.1370/afm.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reid RJ. Patient-centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. Am J Managed Care. 2009;15(9):e71–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]