Abstract

Objective/Hypothesis

Vocal fold vibration is associated with four distinct vibratory patterns: those of the right-upper, right-lower, left-upper, and left-lower vocal fold lips. The purpose of this study was to propose a least squares method to quantify the vibratory properties of each of the four vocal fold lips via videokymography (VKG).

Study Design

This was a methodological study designed to examine the impact of subglottal pressure and line-scan position on mucosal wave parameters.

Methods

VKG, a line-scan imaging technique, has proven to be an effective method for studying vocal fold vibratory patterns. This study used VKG images and an automatic mucosal wave extraction method to examine the vibration of each individual vocal fold lip of 17 excised canine larynges under differing subglottal pressures and line-scan positions.

Results

Varying subglottal pressure led to results consistent with previous studies. Examination of the vocal folds at different line-scan positions along its length revealed that amplitude is greatest at the midpoint of the vocal fold, followed by the anterior portion of the vocal fold, with the posterior portion having the lowest amplitude (P < .001). Frequency and phase delay did not change significantly throughout the length of the vocal fold.

Conclusions

The method used in this study allows for easy determination of four sets of vibratory parameters, and examination of the effect of biomechanical parameters on vocal fold vibrations.

Keywords: Videokymography, mucosal wave, subglottal pressure, line-scan position

INTRODUCTION

Alternating sequences of medial (closing) and lateral (opening) vocal fold movements create the mucosal wave, the primary means whereby the transformation of pulmonary airflow into sound is achieved.1 Characterization of this wave proves to be of great clinical importance as vocal fold vibratory efficiency is reflected by mucosal wave dynamics. A variety of imaging techniques, including stroboscopy, high-speed photography, and videokymography (VKG) have been used to examine and quantify mucosal wave dynamics.1–14 Although effective under most circumstances, stroboscopy cannot accurately model irregular vibratory patterns of the vocal folds.2 High-speed vocal fold imaging methods offer significant advantages over other techniques as they provide visual information of the entire vocal fold. Farnsworth,3 the first to use high-speed imaging techniques, qualitatively described the mucosal wave by observing its phase difference, the difference in the vibratory phase between the upper and lower vocal fold lips. Jiang et al.14 employed high-speed line-scan imaging of excised canine larynges from an infraglottic view to quantitatively examine the effects of airflow, vocal fold elongation, and thyroarytenoid contraction on the mucosal wave. However, high-speed imaging has a number of drawbacks. Not only is it expensive, but the difficulty in analyzing thousands of image frames limits its clinical applicability.4,6 To overcome the limitations of both stroboscopy and high-speed photography, VKG offers a more financially feasible and time-efficient alternative for vocal fold analysis. Rather than using the whole data set from an image, a single line of pixels is extracted from each image, leading to easier measurement of the mucosal wave pattern. In addition, the smaller amount of data used by VKG techniques often results in the ability to use higher imaging rates. Because of these advantages, VKG has been shown to be an effective technique in laryngeal physiology.5–8

Previous studies have focused on the extraction of mucosal wave parameters from the upper and lower lips of the vocal folds.6,7,13,14 However, this is not adequate for describing the complexity of vocal fold vibration, which has four distinct vocal fold vibratory patterns. Four sets of vibratory parameters from VKG imaging offer a more complete picture of mucosal wave patterns and allow for the study of vibratory asymmetry in vocal folds. In addition, the effects of the line-scan position of kymographic extraction on the mucosal wave parameters, including amplitude, frequency, and phase delay, have not been investigated. The purpose of this study was to employ a least squares method to quantitatively extract the mucosal wave parameters of each of the four vocal fold lips while examining how they are affected by subglottal pressure and line-scan position.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Excised Larynx Set-up

Seventeen canine larynges were excised from mongrel dogs euthanized for nonresearch purposes and mounted on an excised larynx set-up. Figure 1 shows the systematic diagram. A small segment of the trachea inferior to the larynx was clamped to a pipe using a hose clamp. The pipe was connected in series to two ConchaTherm III heater-humidifiers (Fisher & Paykel Healthcare Inc., Laguna Hills, CA) and an Ingersoll Rand (type 30) air compressor. The air compressor was used to control subglottal pressure. Before passage through the larynx, the air was conditioned to 35°C to 38°C at 95% humidity. The arytenoid cartilages were held in position by a three-pronged device used to control vocal fold adduction and abduction. A second micrometer system was attached by stitching a rod to the anterior tip of the thyroid lamina. This micrometer system controlled the elongation of the vocal folds.

Fig. 1.

An illustration of the excised larynx set-up.

Several precautions were taken to ensure vocal fold symmetry. First, the excised larynx was carefully examined to make sure both vocal folds had a similar thickness and length. When mounting the larynges on the set-up, we carefully positioned arytenoid cartilages at the same level. Finally, the micrometer systems were applied to symmetrically control the elongation and adduction of the larynges. Despite these measures, asymmetric mucosal wave amplitudes, frequencies, and phase differences were occasionally observed in our experiment.

To investigate the effects of changes in subglottal pressure, it was increased above the phonation threshold pressure to induce oscillation of the vocal folds, and was monitored with an open-ended water manometer (Dwyer No. 1211). Two subglottal pressures (9.0 and 14.0 cm H2O) were applied to drive vocal fold vibrations. A high-speed digital camera (Fastcamultima APX) was mounted on a track system above the vocal folds. This camera was used to record the vocal fold vibrations at a rate of 4,000 frames per second. To study the effects of the line-scan position of the VKG image, we considered three positions along the length of the vocal fold. Line-scan position was measured as a percentage of the vocal fold length beginning at the anterior end; therefore, the midpoint was the 50% position, the point between the midpoint and the anterior end of the vocal fold was the 25% position, and the point between the midpoint and the posterior end was the 75% position.

Least Squares Mucosal Wave Extraction Method

The least squares extraction method involved four steps: digital VKG, threshold-based edge-detection, manual wave segment extraction, and least squares curve-fitting.

After the vocal fold images were recorded, we manually selected the line-scan position with which the kymographic image was made. Next, a global thresholding segmentation algorithm9,10 was applied to extract the glottal edges from the kymographic image. A threshold was selected such that the pixel intensities in the glottis were below the threshold and vocal fold tissue pixel intensities were above it. Once the image had been segmented, the vocal fold edges could be easily determined using a binary edge-detection algorithm.

After determining the vocal fold edge, the vocal fold edge curve must be segmented to differentiate the left and right vocal folds, as well as the upper and lower vocal fold lips. Figure 2 shows the VKG image of the four extracted mucosal wave patterns during vocal fold vibrations, where yα(x) (α = 1, 2, 3, 4) as the functions of the frame number x denote the glottal edges of the right-upper, right-lower, left-upper, and left-lower edges. Because of the inferior-superior wave motion of the vocal folds,8,12 when images were acquired from a superior view, the upper lips of the vocal folds obscured the lower lips during the opening phase of the glottal cycle. During the closing phase of the cycle, the lower lips of the vocal folds were exposed and could be viewed. Thus, the vibratory pattern of the upper lips could be extracted from the opening phase of the glottal cycle and the pattern of the lower lips could be extracted from the closing phase. The glottal edge curve for both the left and right vocal folds was segmented into opening and closing stages, allowing for parameter extraction from the upper and lower lips of both the left and right vocal folds.

Fig. 2.

Detected mucosal waves of a larynx from the VKG image. The vibration of the right upper vocal fold is indicated by the blue line, the right lower by the green line, the left upper by the red line, and the left lower by the yellow line.

Once the vocal fold edge curve had been segmented into four sections, we applied a least squares method to obtain the parameters of each mucosal wave. The vibratory period T was quantitatively determined by an automated cycle counting algorithm. The glottal edge of each mucosal wave can be described as:

| (1) |

where Aa,k denotes the k-th mucosal wave coefficients of yα(x), and α = 1, 2, 3, 4 correspond to the right-upper, right-lower, left-upper, and left-lower mucosal waves, respectively. The following coefficient matrix was defined as:

| (2) |

For the glottal edge series yα(x) with N terms, we have the matrices

| (3) |

and

| (4) |

By minimizing the function (Yα − XαAα)2 for each mucosal wave with N > M, we can obtain the least squares solution of the system parameter matrix Aα as:

| (5) |

Once the optimal values for the coefficient Aα have been determined using the above least squares method, the following fitting function can be applied to describe each mucosal wave from the VKG image:

| (6) |

where denotes the k-th harmonic amplitude, and denotes the k-th phase difference. From this form of the equation, the phase, amplitude, and period of each lip of the vocal folds can be calculated. Equations (1) through (5) give the general solution for the description of a mucosal wave in VKG. Multiple harmonic components of the mucosal wave correspond to multiple vibratory modes of the vocal folds. Recent studies have shown that the vocal folds are dominated by the first few vibratory modes.9–11 The first-order vibratory mode captures over 90% energy of the total energy and the energies of higher order vibratory modes are significantly smaller.9–11 Thus, the mucosal wave can be described by the first few order harmonic components,6,7 and the first-order function was sufficient to estimate the parameters of periodic mucosal waves.

Statistical Analysis

For two subglottal pressures (9.0 and 14.0 cm H2O), the Wilcoxon signed rank test is employed using mucosal wave amplitude, frequency, and phase difference of 17 canine larynges as the dependent variables and the subject group (9.0 and 14.0 cm H2O) as the independent variable. To compare differences in the mucosal wave parameters under three line scan positions (25%, 50%, and 75%), one-way repeated measure ANOVA tests were performed. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all tests.

RESULTS

Figure 2 shows the typical results of four vibratory patterns of a vocal fold detected from VKG using the least squares mucosal wave extraction method. The extracted amplitude and frequency of the right-upper vocal fold were 10.52 pixels and 274.5 Hz, respectively. The amplitude and frequency of the right-lower vocal fold were 10.57 and 279.4, respectively. The phase difference between the right-upper and the right-lower mucosal waves was 22.93 degrees. Similarly, the amplitude and frequency of the left-upper mucosal wave were 22.74 and 274.5, respectively. The amplitude and frequency of the left-lower mucosal wave were 17.40 and 274.5, respectively. The phase difference between the left-upper and the left-lower mucosal waves was 35.54 degrees. The right and left vocal folds displayed asymmetries in amplitude and phase difference, but not frequency.

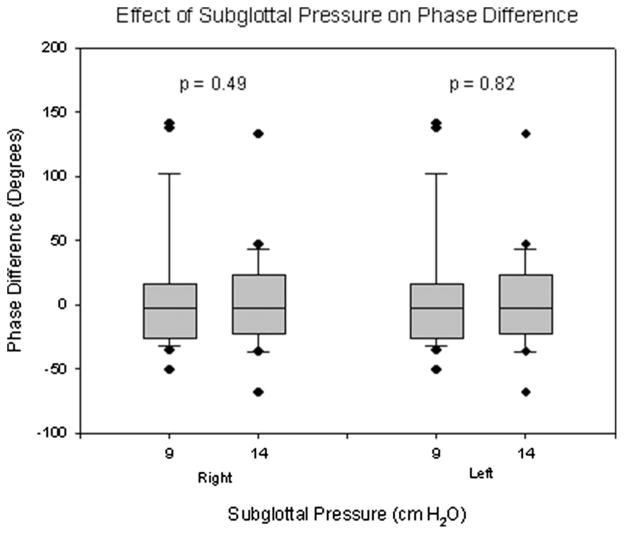

Figures 3 to 5 show the results of mucosal wave analysis under the subglottal pressures of 9.0 and 14.0 cm H2O at the middle (50%) line-scan position for seventeen canine larynges. A summary of the results can be found in Table I. With an increase in subglottal pressure, each of the four vocal fold lips showed a significant increase in amplitude and frequency (P = .012). However, no significant changes in phase difference due to changes in sub-glottal pressure were found in either the left (P = .82) or right (P = .49) vocal fold lips.

Fig. 3.

Effects of subglottal pressure on mucosal wave amplitude of four vocal fold lips. The larynges were tested at 9 and 14 cm H2O.

Fig. 5.

Phase differences in the mucosal wave of four vocal fold lips under differing subglottal pressures.

TABLE I.

Mucosal Wave Parameters Under Differing Subglottal Pressures.

| 9 cm H2O | 14 cm H2O | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude (pixels) | |||

| Right-upper | 9.89 (5.94) | 12.64 (5.67) | .012* |

| Right-lower | 9.27 (6.72) | 13.18 (9.58) | .01* |

| Left-upper | 12.86 (8.71) | 16.52 (7.63) | .005* |

| Left-lower | 9.65 (6.29) | 13.07 (7.06) | <.001* |

| Frequency (Hz) | |||

| Right-upper | 248.96 (84.9) | 280.31(88.5) | <.001* |

| Right-lower | 247.53 (83.0) | 280.80 (89.2) | <.001* |

| Left-upper | 248.15 (84.4) | 279.90 (88.3) | <.001* |

| Left-lower | 247.51 (83.3) | 280.80 (88.8) | <.001* |

| Phase difference (degrees) | |||

| Right | 16.98 (62.08) | 6.77 (47.61) | .49 |

| Left | −2.07 (24.91) | −0.65 (26.13) | .82 |

Means and standard deviations of amplitude, phase difference, and frequency under differing subglottal pressures.

Significant P-value.

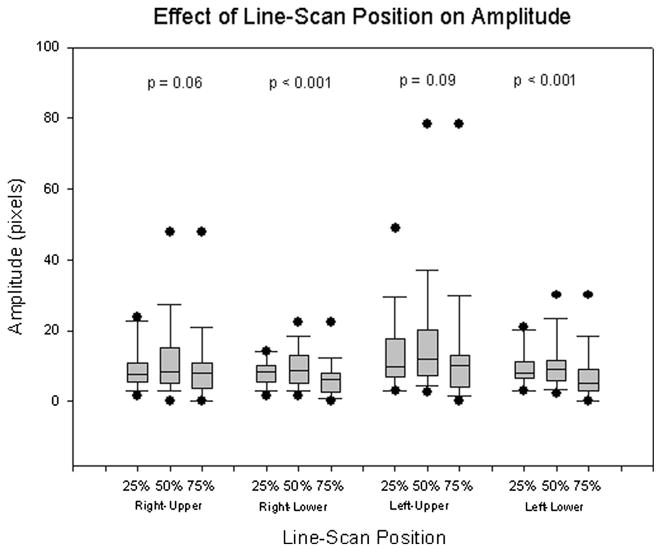

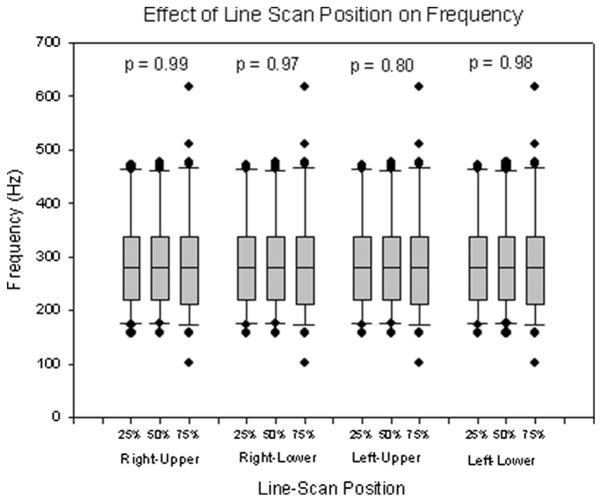

Figures 6 to 8 show the effects of line-scan position on mucosal wave parameters by comparing the results at various line scan positions along the vocal fold. The results are summarized in Table II. When comparing all vocal fold lips, the amplitude at 50% was greatest, followed by that at 25%, and lastly by the amplitude at 75%. For both the lower lip of the right vocal fold and the lower lip of the left vocal fold, the same results were found (P < .001) (Fig. 6). However, there were no significant changes in amplitude found in either the right-upper (P = .06) or left-upper (P = .09) vocal fold lips. Additionally, no significant changes in frequency were found in the right-upper (P = .99), right-lower (P = .98), left-upper (P = .80), or left-lower (P = .99) vocal fold lips, nor were significant changes in phase difference found on either the left (P = .56) or right (P = .17) vocal fold (Figs. 7 and 8).

Fig. 6.

Mucosal wave amplitudes of four vocal fold lips under differing line-scan positions.

Fig. 8.

Phase differences in the mucosal wave of four vocal fold lips as a function of line-scan position.

TABLE II.

Mucosal Wave Parameters Under Different Line-Scan Positions.

| 25% | 50% | 75% | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amplitude (pixels) | ||||

| Right-upper | 8.98 (6.10) | 11.90 (10.86) | 9.12 (10.82) | .06 |

| Right-lower | 8.34 (3.60) | 9.23 (5.34) | 6.08 (5.15) | <.001* |

| Left-upper | 13.85 (11.14) | 16.61 (17.49) | 12.62 (17.71) | .09 |

| Left-lower | 9.50 (5.14) | 10.64 (7.38) | 7.40 (7.36) | <.001* |

| Frequency (Hz) | ||||

| Right-upper | 290.19 (90.88) | 286.39 (84.96) | 291.70 (98.43) | .99 |

| Right-lower | 289.59 (90.78) | 289.46 (91.69) | 282.63 (98.93) | .98 |

| Left-upper | 289.65 (91.28) | 290.50 (91.64) | 272.61 (81.93) | .80 |

| Left-lower | 289.74 (90.66) | 290.31 (91.63) | 295.35 (117.23) | .99 |

| Phase difference (degrees) | ||||

| Right | −1.83 (10.39) | 17.94 (31.76) | 11.92 (35.20) | .17 |

| Left | 2.51 (30.10) | 5.96 (26.25) | 13.70 (35.20) | .56 |

Means and standard deviations of amplitude, phase difference, and frequency under differing line-scan positions.

Significant P-value.

Fig. 7.

Mucosal wave frequency of four vocal fold lips at different line-scan positions.

DISCUSSION

This study examines the effects of subglottal pressure and line-scan position on mucosal wave parameters including frequency, amplitude, and phase delay. Increases in subglottal pressure were associated with amplitude increases in all four vocal fold lips, but these changes were most pronounced in the lower vocal fold lips (Fig. 3). The slightly greater increase in amplitude in the lower lips as compared with the upper lips may indicate that increases in subglottal pressure have a greater impact on the oscillations of the lower vocal fold. The increase in frequency due to increased subglottal pressure was fairly uniform across all vocal fold lips (Fig. 4). Phase difference, which is dependent on both the mucosal wave propagation velocity and the frequency of oscillation, did not show significant changes due to differing subglottal pressures in either the left or right vocal fold (Fig. 5). This finding is likely due to the fact that as frequency increased as a result of increased subglottal pressure, the propagation velocity increased proportionately, resulting in little change in phase difference. Asymmetries in amplitude, frequency, and phase delay were occasionally found in the data, such as in the case presented in Figure 2. The asymmetries in amplitude and phase difference may be associated with uncontrollable asymmetric biomechanical parameters, such as the mass, stiffness, and tension of the two vocal folds.

Fig. 4.

Mucosal wave frequencies of four vocal fold lips under differing subglottal pressures.

The use of VKG data in this study allows for the extraction of mucosal wave parameters from varying positions along the length of the vocal fold. Changes in line-scan position resulted in significant differences in amplitude only in the two lower vocal fold lips. As observed when changing subglottal pressure, it appears that the amplitude of the lower vocal fold lips is affected more by changes in line-scan position than the upper vocal fold lips. The pattern found in vocal fold amplitude, that of greatest amplitude at the 50% position, followed by the 25% position, with the 75% position having the smallest amplitude (Fig. 6), may be due to the dampening of mucosal wave amplitude on the posterior end of the vocal folds by the arytenoid cartilages. The frequency of each of the four lips did not show any significant changes due to differing line-scan positions (Fig. 7), nor did any significant changes in phase difference emerge in either the left or right side of the vocal fold (Fig. 8). As amplitude is the only parameter affected by spatial variations, it is likely that mucosal wave propagation velocity is constant along the length of each vocal fold.

VKG imaging techniques have been used to extract mucosal wave parameters of the upper and lower vocal fold lips.6,7,13,14 Jiang et al.6 examined the upper and lower lips of one vocal fold at the midpoint of the glottis; however, their method was not conducive to the analysis of asymmetric vibratory patterns. The present study represents an improvement over this and other previous image analysis methods, as all four vocal fold lips were examined at three positions along the length of the glottis. By using a least squares method, we can quantitatively extract mucosal wave parameters from the left and right vocal folds on both the top and bottom lips, facilitating investigation of asymmetries in vocal fold parameters, as shown in Figure 2. Thus, the new method can be applied to cases of certain pathologies, such as unilateral vocal fold paralysis, which result in asymmetric vocal fold vibration.15

In addition, since Jiang et al.6 only considered the first- and second-order harmonic components of the mucosal wave, their methods were only applicable for nearly periodic signals and, therefore, were insufficient for other complex mucosal wave patterns with higher order components. As shown in Eq. (1), the present study uses a more general Fourier description including multiple harmonic components, which may make it possible to analyze complex mucosal waves with higher-order components. More importantly, Jiang et al.’s6 study employed nonlinear curve-fitting methods to approximate vocal fold patterns and extract vocal fold parameters. The error associated with nonlinear curve-fitting significantly increases, whereas the stability of the algorithm drastically decreases, with an increase in the harmonic components. The present study determines the mucosal wave coefficients as the least square solution of a linear matrix equation. This algorithm allows us more stability and higher accuracy for the extraction of multiple mucosal wave parameters. The use of VKG also enables the user to study any specific position along the length of the vocal fold, rather than merely studying the motion at a single point, as was done in previous studies.6,7,13,14 Together, these aspects create a more complete and accurate picture of vocal fold vibration.

Accurate assessment of vocal fold vibratory properties is of great importance, as proper analysis aids in the assessment and treatment of vocal fold pathologies.16–18 Vocal fold pathology commonly results in mucosal wave asymmetries.17–21 Vocal fold scarring changes tissue properties, including vocal fold tension. Increased stiffness associated with vocal fold scarring is manifested in the mucosal wave by asymmetries in mucosal wave amplitude, with scarred vocal fold lips showing reduced amplitude.13 Vocal fold cysts result in a decrease in the mucosal wave, whereas vocal fold polyps often result in an increase in the mucosal wave.18 Analyses of mucosal wave properties of laryngeal tuberculosis patients reveal asymmetries not only in amplitude, but phase as well.19 The method of analysis used in this study, which allows for examination of the mucosal wave at any point along the length of the vocal fold, as well as the inspection of each individual vocal fold, allows one to identify specific areas of vibratory asymmetries, thus increasing the ease with which vocal fold pathologies can be identified.

This study presents and demonstrates the validity of a new method of mucosal wave parameter detection from VKG images in excised larynges. Excised larynx experiments facilitate direct observation and measurement of vocal-fold vibrations, and have proven to be advantageous in the study of voice physiologies.22,23 In these experiments, the biomechanical parameters controlling phonations, such as subglottal pressure, can be systematically monitored and independently controlled; something that is difficult to achieve in human subjects. In addition, canine and human larynges possess physical similarities that allow the canine larynx to be used as an organic model for studying mechanisms of human phonation. Because of these advantages, excised larynx experiments represent a valuable and important methodology for the study of laryngeal physiology. The established method based on excised larynges has potential as a diagnostic tool and could be useful to clinicians by providing them with a method which analyzes VKG data from patients with both normal voices and laryngeal pathologies.

CONCLUSION

A least squares method is proposed to quantitatively extract parameters of right-upper, right-lower, left-upper, and left-lower vocal fold lips via VKG. The mucosal wave parameters of amplitude, frequency, and phase difference were examined under different subglottal pressures and line-scan positions. This method also allowed for examination of each of the vocal fold lips individually and at any point along the length of the vocal fold, providing a more complete picture of the mucosal wave than a single line VKG. The proposed algorithm might provide advantages in examining vibratory patterns of the four vocal fold lips during excised larynx experiments. Its application to VKG data from patients with laryngeal pathologies will be the subject of future research.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by NIH grant number 1-R01 DC05522 from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Bless DM, Hirano M, Feder RJ. Videostroboscopic evaluation of the larynx. Ear Nose Throat J. 1987;66:48–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svec JG, Schutte HK. Videokymography: high-speed line scanning of vocal fold vibration. J Voice. 1996;10:201–205. doi: 10.1016/s0892-1997(96)80047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farnsworth DW. High-speed motion pictures of the human vocal cords. Bell Lab Records. 1940;18:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson H, Hertegard S, Lindestad P, Hammarberg B. Vocal fold vibrations: high-speed imaging, kymography, and acoustic analysis: a preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:2217–2122. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200012000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung MW, Kim KH, Koh TY, et al. Videostrobokymography: a new method for quantitative analysis of vocal fold vibration. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1859–1863. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199911000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang JJ, Chang CB, Raviv JR, Gupta S, Banzali FM, Hanson DG. Quantitative study of mucosal wave via videokymography in canine larynges. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1567–1573. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200009000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu Q, Schutte HK, Gu L, Yu Q. An automatic method to quantify the vibration properties of human vocal folds via videokymography. Folia Phoniatr. 2003;55:128–136. doi: 10.1159/000070724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schutte HK, Svec JG, Sram F. Videokymography: research and clinical issues. Log Phon Vocal. 1997;22:152–156. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y, Jiang JJ. Spatiotemporal chaos in excised larynx vibrations. Phys Rev E. 2005;72:035201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.72.035201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Jiang JJ, Tao C, Bieging E. Quantifying the complexity of high-speed image series in excised larynx experiments: spatiotemporal and nonlinear dynamic analyses. Chaos. 2007;17:043114. doi: 10.1063/1.2784384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neubauer J, Mergell P, Eysholdt U, Herzel H. Spatiotemporal analysis of irregular vocal fold oscillations: biphonation due to desynchronization of spatial modes. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001;110:3179. doi: 10.1121/1.1406498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsushita H. The vibratory mode of the vocal folds in the excised larynx. Folia Phoniatr. 1975;27:7–18. doi: 10.1159/000263963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Titze IR, Jiang JJ, Hsaio T. Measurement of mucosal wave propagation and vertical phase difference in vocal fold vibration. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:58–63. doi: 10.1177/000348949310200111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang JJ, Yumoto E, Lin SJ, Kadoto Y, Kurokawa H, Hanson DG. Quantitative measurement of mucosal wave by high-speed photography in excised larynges. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107:98–102. doi: 10.1177/000348949810700203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Titze IR. Voice disorders. In: Titze IR, editor. Principles of Voice Production (second printing) Iowa City, IA: National Center for Voice and Speech; 2000. pp. 345–367. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan Y, Ahmad K, Kunduk M, Bless D. Analysis of vocal fold vibrations from high-speed laryngeal images using Hilbert transform-based methodology. J Voice. 2005;19:161–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benninger MS, Alessi D, Archer S, et al. Vocal fold scarring: current concepts and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;115:474–482. doi: 10.1177/019459989611500521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shohet JA, Courey MS, Scott MA, Ossoff RH. Value of video-stroboscopic parameters in differentiating true vocal fold cysts from polyps. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:19–26. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199601000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Argwal P, Bais AS. A clinical and videostroboscopic evaluation of laryngeal tuberculosis. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:45–48. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100139878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haben CM, Kost K, Papagiannis G. Mucosal wave asymmetries in the clinical voice laboratory. J Otolaryngol. 2002;31:275–280. doi: 10.2310/7070.2002.43298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Jiang JJ. Chaotic vibrations of a vocal fold model with a unilateral polyp. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115:1266–1269. doi: 10.1121/1.1648974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van den Berg J, Tan TS. Results of experiments with human larynxes. Pract Otorhinolaryngol (Basel) 1959;21:425–450. doi: 10.1159/000274240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang JJ, Titze IR. A methodological study of hemilaryngeal phonation. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:872–882. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199308000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]