Abstract

An in vitro tissue construct amenable to perfusion was formed by randomly packing mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-embedded, endothelial cell (EC)-coated collagen cylinders (modules) into a microfluidic chamber. The interstices created by the random packing of the submillimeter-sized modules created EC-lined channels. Flow caused a greater than expected amount of contraction and remodeling in the modular constructs. Flow influenced the MSC to develop smooth muscle cell markers (smooth muscle actin-positive, desmin-positive, and von Willebrand factor-negative) and migrate toward the surface of the modules. When modules were coated with EC, the extent of MSC differentiation and migration increased, suggesting that the MSC were becoming smooth muscle cell– or pericyte-like in their location and phenotype. The MSC also proliferated, resulting in a substantial increase in the number of differentiated MSC. These effects were markedly less for static controls not experiencing flow. As the MSC migrated, they created new matrix that included the deposition of proteoglycans. Collectively, these results suggest that MSC-embedded modules may be useful for the formation of functional vasculature in tissue engineered constructs. Moreover, these flow-conditioned tissue engineered constructs may be of interest as three-dimensional cell-laden platforms for drug testing and biological assays.

Introduction

Using a modular approach, vascularized tissue can be created by embedding functional cells within submillimeter-sized collagen cylinders (modules) while the outside surfaces are seeded with endothelial cells (EC). The void spaces created by randomly packing the modules into a container form EC-lined tortuous channels through which blood perfusion can occur. With whole blood perfusion, the EC delay clotting times and inhibit the loss of platelets.1 In this study, we used a microfluidic system2 with embedded bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) to assess their effect on remodeling under in vitro conditions. Remodeling is appearing to be a critical and not well understood determinant of the in vivo fate of tissue constructs, and this system allows us to study this process in the absence of the additional complexity provided by the host response. These flow-conditioned constructs may also be of interest as tissue mimics for in vitro bioassays.

MSC are a ready, plastic cell source whose niche may be perivascular in origin.3 They are plastic adherent and can be differentiated into muscle, bone, fat, neural, cartilage, tendon, dermal, vascular, and hepatic cells. Soluble factors,4 oxygen tension,5 and mechanical stimuli such as shear stress6 influence their differentiation. MSC secrete growth factors and cytokines whose effects can enhance the survival and performance of tissue engineered constructs. Among their positive effects in different contexts are the inhibition of apoptosis and fibrosis, the stimulation of angiogenesis, the stimulation of tissue-specific and tissue-intrinsic progenitors, and the ability to turn off T-cell surveillance and chronic inflammatory processes in allogeneic implants.7 For example, in the context of producing vascular grafts in severe combined immunodeficiency mice, MSC stabilized the nascent human umbilical vein EC within an engineered blood vessel, which remained stable and functional for longer than 130 days in vivo.8 The soluble factors platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-B, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)9 have been implicated in the function of MSC in blood vessel maturation.9,10

When implanted into rats treated with immunosuppressant drugs (atorvastatin and tacrolimus), donor EC migrated from the surface of modules without embedded cells and formed chimeric perfusable vessels containing host and donor cells that persisted for at least 60 days.11 Embedding MSC within modules accelerated vessel formation and maturation in vivo, with the MSC appearing to differentiate into smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive pericyte-like cells that integrated with the new vasculature.12

The objectives of this article were to assess the remodeling of the MSC+EC modular constructs in vitro over 21 days subject to flow in a microfluidic chamber.2 Others have used similar microfluidic systems to combine three-dimensional co-cultures and flow (reviewed in13). For example, in a proof-of-principle study that demonstrated the ability to control forces and biochemical gradients, EC migrated from one microfluidic channel through a collagen wall toward a parallel cancer cell–containing channel.14

EC were tracked using von Willebrand factor (vWF) and CD31 (or platelet EC adhesion molecule) stains while MSC differentiation into smooth muscle-like cells was tracked using the smooth muscle cell (SMC) markers SMA and desmin. The size changes in the modules over time were also measured to reveal macroscopic remodeling differences between static and flow conditions.

Materials and Methods

Module fabrication and culture

Modular collagen cylinders were fabricated as described previously.1 Briefly, collagen (with or without embedded cells) was drawn into poly(ethylene) tubing, gelled, and cut into segments using an automatic cutter. The gelled collagen cores were released from the poly(ethylene) using a vortex mixer, and, if co-cultures were required, modules were optionally seeded with a confluent surface layer of EC. Three module systems were used in this study: (1) surface-seeded EC only, (2) embedded MSC only (no EC), and (3) surface-seeded EC with embedded MSC. To coat modules, modules (1 mL) were incubated in 10 mL of EC suspension at a concentration of 250,000 cells/mL, as detailed previously;1 this was sufficient to generate confluent EC monolayers. Sprague-Dawley rat aortic EC (up to passage 5, VEC Technologies, Rensselaer, NY) were used. MSC were isolated from male Sprague-Dawley rats, as described previously,15 in a protocol approved by the University of Toronto animal care committee. MSC were added to the collagen solution before gelation at a concentration of 1x106 cells/mL. The MSC were used at passage 2 and were negative for CD11b, CD34, and CD31 and positive for CD90 and CD29. Modules were loaded into microfluidic chambers and perfused with a 1:1 mixture of EC:MSC culture medium consisting of MCDB-131 complete medium (VEC Technologies) and Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Burlington, Canada). This was similar to the 1:1 ratio of EC:MSC culture medium previously used by others.16 MSC cultured in EC medium (containing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)) are known to differentiate toward an EC phenotype characterized by the development of several markers, including CD31, kinase insert domain receptor (KDR), and fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor (FLT)-1.17–19

Chamber and flow circuit fabrication

Microfluidic remodeling chambers were fabricated, and flow circuits were assembled as described previously.2 For remodeling chambers subjected to flow, flow was linearly increased from 0 to 0.5 mL/min over the course of 4 hours, culture medium was exchanged every 2 days, and flow was maintained for up to 21 days at a rate of 0.5 mL/min. Between three and six replicates were performed for each condition and time point.

Histological analysis

At the 7-, 14-, or 21-day time point, remodeling chambers were perfused at 37°C and 5% carbon dioxide with 5% buffered formalin (Sigma) at a rate of 0.5 mL/min for 30 minutes. Chambers were cut open, and modular tissues were retrieved and embedded in a block made of 5% agarose (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Serial sections 50 μm apart were prepared for histology. Antibody stains were rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig)G CD31 (1:2,000 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), mouse IgG desmin (1:200 dilution, DAKO, Mississauga, Canada), sheep IgG vWF (1:5,000 dilution, Cedarlane, Burlington, Canada), and rabbit IgG SMA (1:1,000 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, MA). All secondary antibodies (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlington, Canada) were used at a 1:200 dilution. Normal rat tissues served as positive controls, and modular construct serial sections treated with secondary antibody alone served as negative controls. Additional stains were Masson's Trichrome for collagen, Alcian blue (pH 2.5) for acidic proteoglycans, and von Kossa for calcium and calcium salts.

Image analysis

The dimensions of individual modules and modular constructs were measured from images using ImageJ (version 1.42q, National Institutes of Health). Each image was scale calibrated individually to ensure accuracy. To determine the porosity of the construct, images were calibrated for size measurements, converted to 8 bits, and threshold adjusted, and the area that the modules occupied was quantified using the analyze particles function.

Histology slides were imaged using a Zeiss Axiovert light microscope equipped with a 10× objective and a charge coupled device camera such that images were 3.3×105 μm2 in area. Using ImageJ, the number of SMA+, desmin+, and CD31+ cells were manually counted, as was the total number of cells present within each image. Up to eight images were taken for each remodeling chamber, and the average number of cells for each chamber was determined. These values were then averaged over the set of biological replicates (the total number of remodeling chambers for each experimental condition), which ranged from three to six. In some cases, the number of positive cells was divided by the total number of cells to determine population proportions. After raw images were analyzed and quantified, illustrative figures were prepared, and whole images were white balanced for added clarity, following the guidelines of Rossner and Yamada.20

Flow characterization

The sphericity factor (ϕ, the ratio of the surface area of the module to the surface area of a sphere of equal volume) of each module type was calculated using Equation 1 (using the measured module length [Lm] and diameter [dm]) and used as a correction factor for packed bed equations originally derived using spherical particles rather than cylindrical modules.

|

(1) |

Immediately after loading modules into the remodeling chambers and before flow, the initial length, Lc, and porosity, ɛ, of the packed module construct were determined through image analysis. The porosity, ɛ, was determined using Equation 2, where Vm is the total volume that the modules occupied within the remodeling chamber, and VT is the empty chamber's volume.

|

(2) |

To determine the Reynolds number within the remodeling chamber, a modified equation for packed beds, Equation 3, was employed.

|

(3) |

In Equation 3, ρf is the density of the cell culture medium, and μ is the viscosity of the culture medium (both assumed to be equal to water at 37°C). Flow was considered laminar when Re* was less than 10.21

The average shear stress within the packed module bed, τ*, was estimated using Equation 4, where Us is the superficial velocity.1,22

|

(4) |

Because the constructs were continually remodeling, the quantities defined by Equations 3 and 4 changed over time, so the reported value of Re* and τ* are the initial values.

Statistical analysis

All data were normally distributed (as determined using Q-Q plots), and independent sample means were compared using the Student t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Tukey honestly significant difference multiple-comparison correction. Differences were considered statistically significant if p<0.05.

Results

Construct characterization

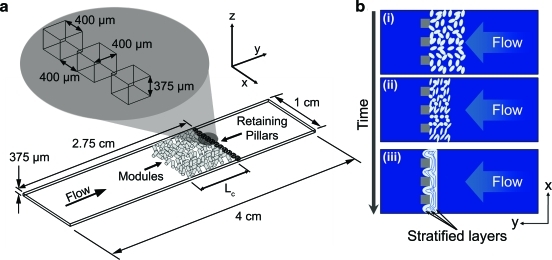

The starting values of ɛ, Re*, and τ* that describe the three modular systems are found in Table 1. Differences between the module diameters and sphericity for each system caused the small differences in these values. The flowing cell culture medium compacted modules packed into the remodeling chamber. Compaction reduced the length of the modular construct and the amount of void space throughout. As time progressed, cell-driven remodeling acted to shrink the size and porosity of the construct further. The combination of compaction and cellular contraction produced a construct with stratified layers (Fig. 1b). Under light microscopy, these layers appeared as packed, compressed rows of modules that were, for the most part, parallel to the retaining pillar wall. By day 21, the majority of flow channeled around the edges of the construct and did not percolate through it. Thus, although we compare the remodeling that occurred with and without flow, we do not imply that the long-term effects are associated with shear stresses on the EC as in an in vivo situation.

Table 1.

Initial Values for Characteristic Parameters of Modular Constructs (N=40)

| Module Type | Module diameter, μm | Module sphericity factor | Module bed porosity | Reynolds number | Average shear stress through the packed module bed,dyn/cm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | 575 | 1.22 | 0.40 | 3.75 | 3.04 |

| MSC | 628 | 1.27 | 0.42 | 4.38 | 2.41 |

| MSC+EC | 463 | 1.21 | 0.37 | 2.82 | 4.80 |

EC, endothelial cells; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells.

FIG. 1.

(a) Schematic of the remodeling chamber. With flow, modules packed against the retaining pillars while the interconnected void spaces between cylindrical modules facilitated percolation. Lc is the length of the packed module bed. (b) Modular constructs (i) experienced instantaneous compaction with flow (ii). The cells within the construct then remodeled this compacted mass (iii). Larger void spaces collapsed, and stratified module layers became apparent at day 21 (iii). Layers were oriented perpendicular to the incoming flow and spanned the width of the chamber, as shown. At later time points (14 and 21 days), portions of the modular tissue squeezed through the retaining pillars up to a depth of approximately 450 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

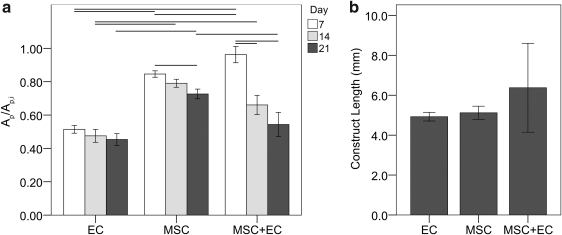

For static controls, the EC-only modules contracted the most, followed by MSC+EC modules; MSC-only modules contracted the least (Fig. 2a). EC-only modules contracted the fastest, and their sizes appeared to stabilize after 7 days, whereas shrinkage was more prolonged for MSC-containing modules and continued through to day 21 (p<0.05, ANOVA), although none of the modular constructs experiencing flow appeared to have any difference in final size (p=0.68, ANOVA F-test, Fig. 2b), suggesting that flow stimulated the MSC to enhance the amount of contraction, at least in the MSC-only case.

FIG. 2.

(a) Shrinkage of statically cultured modules (EC, MSC, and MSC+EC modules). Ap/Ap,i is the ratio of the projected area of the modules (Ap) to their initial projected area at time 0 (Ap,i). Connecting lines indicate a statistically significant difference (p<0.05 according to analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey honestly significant difference, n=30), and error bars are standard error of the mean (SEM). At day 7, MSC+EC modules were the largest, followed by MSC-only and finally EC-only modules. After 7 days, EC-only modules did not show any further significant shrinkage, whereas MSC-containing modules continued to shrink to day 21. By the 21st day, both types of EC-containing modules reached the same size and were smaller than their MSC-only counterparts. (b) Experimentally measured construct sizes within the remodeling chamber (Lc, Fig. 1a) at day 21. No statistically significant differences were found between the three groups according to ANOVA (p>0.05), and constructs appeared to achieve approximately the same final length, which contrasted with the results from the statically cultured modules, in which EC-containing modules contracted the most. Error bars are±SEM and n=4 or 5. EC, endothelial cells; MSC, mesenchymal stromal cells.

Construct matrix and cellularity

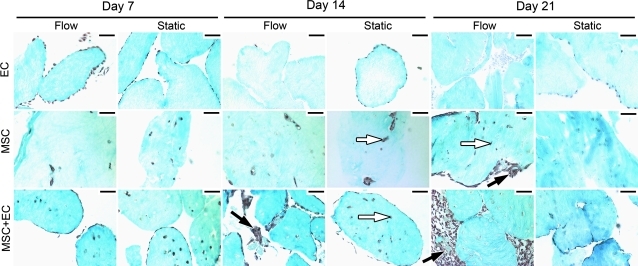

Flow appeared to induce embedded MSC to migrate from the interior of individual modules toward the perimeter (Fig. 3). This migration was not observed in static controls. The presence of EC appeared to enhance the migration to the surface. Few (or even no) cells were found embedded within MSC+EC modules after 21 days of flow, and all cells appeared to lie near or in the intermodular region (the region between individual modules); the MSC appeared to be outside the modules and in the channels between modules. This contrasts with the 21-day MSC-only flow case, which showed cells within the modules and intermodular regions. Moreover, in MSC-only flow cases, migration began between days 14 and 21, whereas it began earlier (between days 7 and 14) for MSC+EC flow cases.

FIG. 3.

Cell migration and loss over time. Collagen was stained with trichrome and appear blue, whereas nuclei appear dark brown. For EC-only modules, EC appeared to remain along the surface of static controls, whereas flow caused loss of cells over time. For modules with embedded MSC (with or without EC), flow appeared to cause a migration of cells from the interior of the modules (white arrows) toward the outer surfaces and the intermodular regions (black arrows). By day 21, MSC-only modules experiencing flow had more cells in the intermodular regions and more total cells than their corresponding static controls. This effect was accelerated in MSC+EC modules and was apparent by day 14. By day 21, MSC+EC modules with flow had more cells than static controls, and these cells were present in the intermodular region, which contrasts with the static controls, in which cells were found primarily within the modules. Scale bars=100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

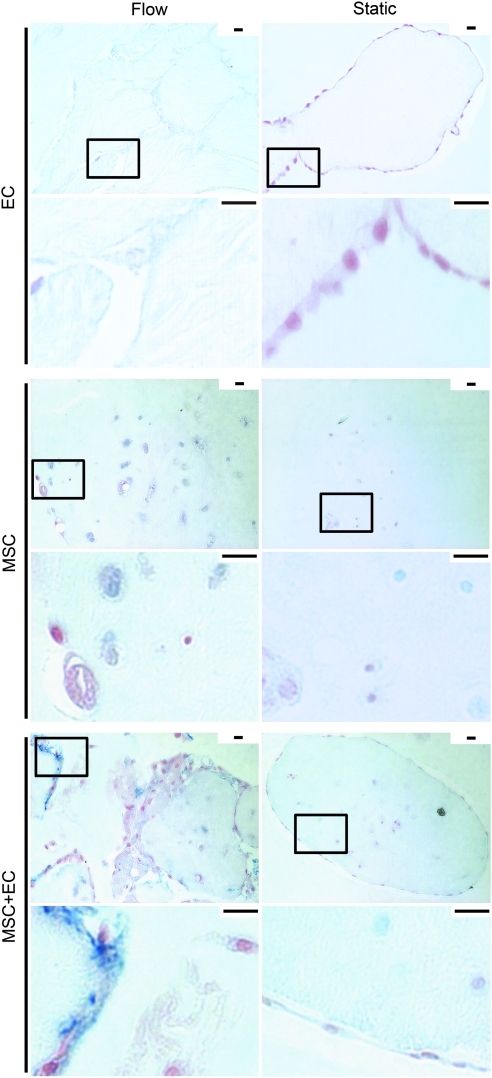

Not surprisingly, the nature of the extracellular matrix (ECM) with MSC under static and flow conditions was different than with EC only. Alcian blue staining (Fig. 4) revealed a greater amount of proteoglycan deposition for MSC-containing constructs. For the MSC+EC modules, there was heterogeneous proteoglycan deposition. A number of large deposits were seen in the intermodular region, suggesting that the migrated MSC had produced new matrix while in this region.

FIG. 4.

Proteoglycan staining of modular constructs. At day 14, large differences in blue proteoglycan staining (Alcian blue, pH 2.5) were observed between the EC, MSC, and MSC+EC conditions. Nuclei were counterstained in red. Low- and high-magnification images are shown, with the boxes in the low-magnification images showing the location of the higher-magnification image. These differences were not seen at earlier times. For EC-only modules under flow, neither cell nor proteoglycan staining was observed, whereas static controls showed cells (on the module periphery (red)) but no proteglycan staining. In MSC-only modules, a small cloud of proteoglycan surrounded embedded MSC with flow (visible in the higher-magnification images), which was not seen in static controls. For MSC+EC modules, more cell and proteoglycan staining was observed within the intermodular regions (on the periphery of the modules) with flow. This contrasted with the lack of staining in static controls, which was similar to that of the MSC-only static controls. Thus, it appeared that flow enhanced the amount of proteoglycan synthesis for flow-conditioned constructs, illustrating changes in the overal remodeling process. Scale bars=25 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

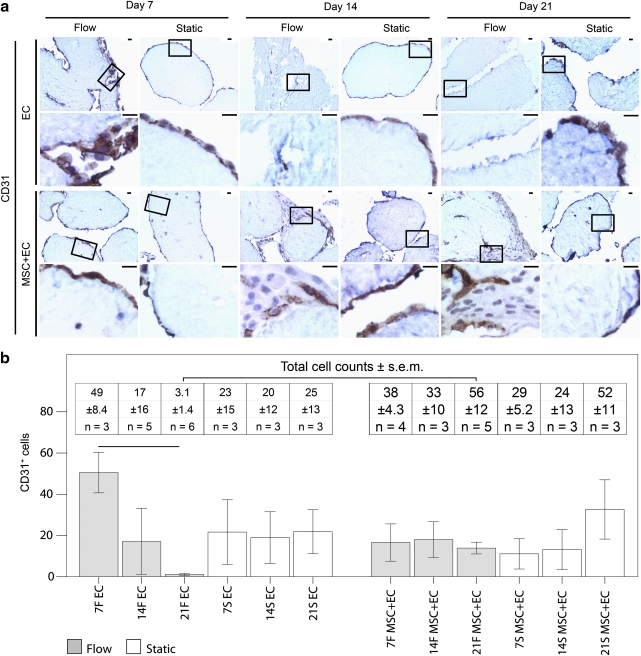

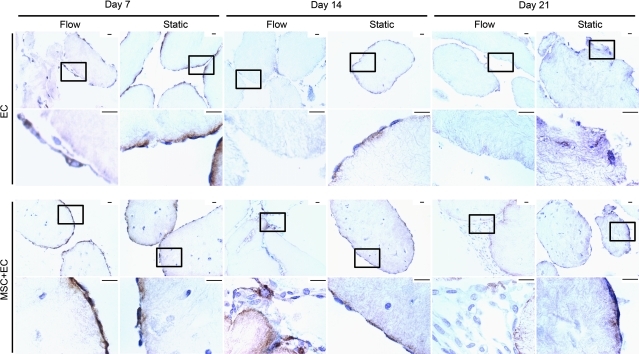

EC coverage

EC coverage was tracked using CD31 and vWF (Figs. 5 and 6). Only CD31 was used for quantification because vWF slides had higher background staining, which compromised accurate cell counts. Only cells with CD31 membrane staining were counted because those lacking this characteristic membrane staining have impaired function.23 In general, we observed fewer functional EC over time with flow, although the presence of MSC appeared to mitigate this decrease. As seen in Figure 5b, there were fewer CD31+ EC in the flow cases than in their corresponding static controls. By day 21, virtually no vWF+ EC remained with or without MSC (Fig. 6), although there were some CD31+ cells under flow and static conditions.

FIG. 5.

(a) CD31 (brown) expression in modular constructs. Nuclei appear blue. The boxes in the low-magnification images (upper rows) show the location of the high-magnification images (lower rows). Static EC-only modules showed membrane-stained CD31+ cells around their perimeters, whereas flow cases showed some at day 7 but fewer at days 14 and 21. For MSC+EC modules under static and flow conditions, cells with CD31 membrane staining were apparent around the perimeter of the modules and within the intermodular regions, although their distribution appeared sparse. No membrane-stained CD31+ cells were observed in MSC-only cases (data not shown). Scale bars=25 μm. (b) The effect of flow and MSC on EC. The number of membrane-stained CD31+ cells (bars) and the total number of cells (inset table) found within an average 10×microscope field of the histological sections of the modular constructs. Unlike static EC-only modules, flow-conditioned EC-only modules had significantly fewer CD31+cells over time, indicating that the loss of EC was linked to flow. When MSC were added to the system, the sharp decline in the number of CD31+ cells in flow cases was not observed, suggesting that the MSC mitigated the complete loss of EC. That day 21 MSC+EC flow cases had more total cells than day 21 EC-only flow cases reflects the loss of EC in EC-only cases and the presence of the MSC in MSC+EC cases. Connecting lines represent a statistically significant difference between conditions (p<0.05, ANOVA), all error bars are±SEM, and the number of analyzed remodelign chambers (n) is shown in the inset table. F, flow; S, static. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

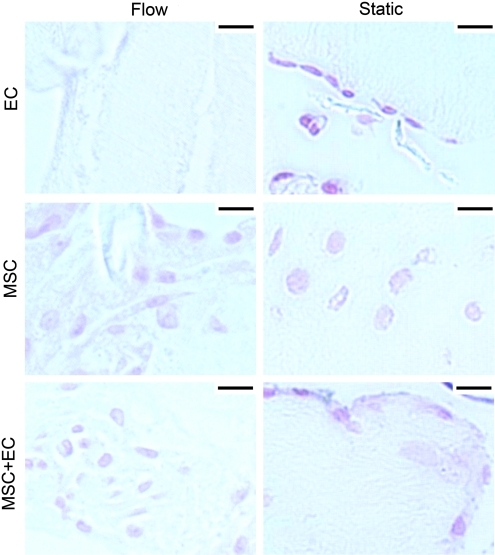

FIG. 6.

Von Willebrand factor (vWF) staining over time. Boxes in the low-magnification upper rows show the location of the high-magnification images in the lower rows. EC were stained for vWF (brown), and nuclei appear blue. Throughout the 21-day timecourse, MSC-only constructs did not stain positive for vWF and were omitted from this figure. For EC-only modules, static controls showed EC coverage through to 21 days, and flow cases showed a complete loss of EC by day 14. Embedding MSC appeared to enhance the short-term retention of EC experiencing flow. At day 7, EC attachment under static and flow conditions appeared similar for MSC+EC modules. On day 14 of flow, the MSC appeared to delay the drastic loss of EC because vWF+ cells were observed, but by day 21, few (if any) vWF+ cells were seen. Scale bars=25 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

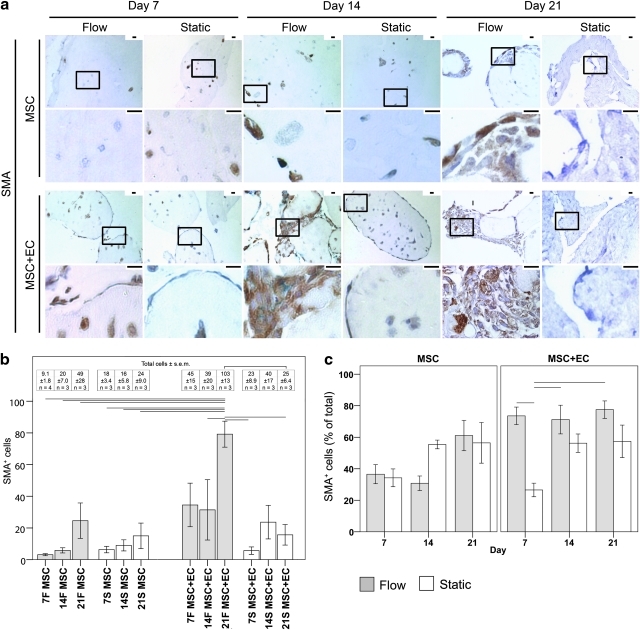

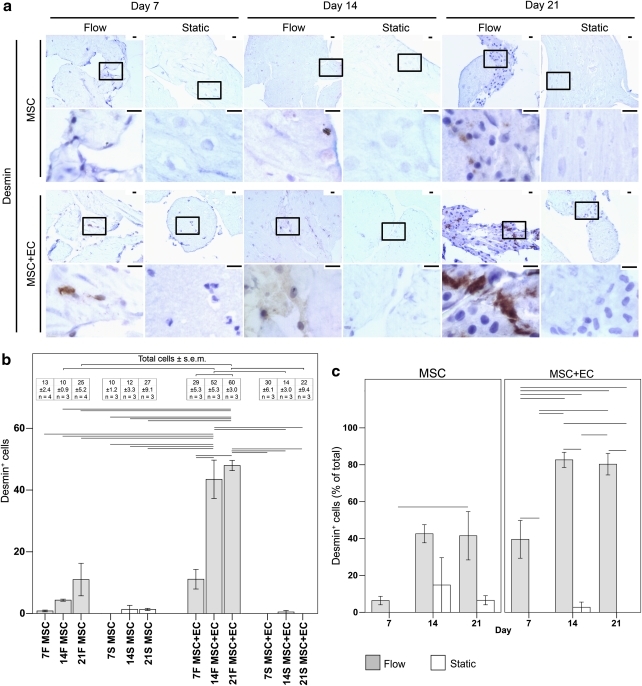

MSC phenotype and differentiation

When the MSC were embedded within modules and placed into remodeling chambers, several markers of MSC differentiation were examined. These included SMA and desmin, which are two SMC markers (Figs. 7 and 8, respectively). Calcium mineralization was also tracked (von Kossa, Fig. 9) to determine whether the MSC were differentiating toward an osteocyte lineage.

FIG. 7.

(a) Low- and high-magification images of MSC differentiation into smooth muscle actin (SMA)+ (brown) cells. Nuclei appear blue. The boxes in the low-magnification images (upper rows) show the location of the high-magnification images (lower rows). No SMA staining was observed in EC-only modules (data not shown). For static MSC-only modules, SMA+ cells were sparsely located throughout the modular construct. With flow, the MSC migrated toward the intermodular region, and by day 21, SMA+ cells were found around the surface of modules, as well as within the intermodular spaces. The presence of EC and flow appeared to accelerate the appearance of SMA staining and the MSC migration such that many SMA+ cells were observed in the intermodular region at day 21. Scale bars=25 μm. (b) The effect of flow and EC on MSC differentiation into SMA+ cells. The graph shows the number of SMA+ cells (bars) and the total number of cells (inset table) found within the average 10×field of the constructs' histological sections. The number of SMA+ cells in MSC-only cases was similar for both static and flow conditions. When EC were added to the system, static cases showed no changes in the number of SMA+ cells, but when flow was added to the system, significantly more SMA+ cells were observed, suggesting that the flow-conditioned EC were guiding the differentiation of MSC into SMA+ cells. The day 21 increase in SMA+ cells under the MSC+EC flow conditions resulted in concomitantly more total cell numbers than in the corresponding day 21 MSC+EC static controls. Differentiation of existing MSC and MSC proliferation followed by differentiation probably caused the greater number of SMA+ cells. (c) The effect of flow on the population of SMA+ cells. The ratio of SMA+ cells to the total number of cells was used to determine the percentage of SMA+ MSC. For MSC-only constructs, no statistically significant differences in the population of SMA+ cells were observed under static or flow conditions, but for MSC+EC constructs, flow caused an immediate increase in the proportion of SMA+ cells at day 7, illustrating the ability of flow and EC to accelerate MSC differentiation into SMA+ cells. The SMA+ cells also remained the dominant cell type, despite the presence of EC. Connecting lines represent statistically significant differences between conditions (p<0.05, ANOVA); all error bars are±SEM, and number of analyzed remodeling chambers is given in the inset table. F, flow; S, static. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

FIG. 8.

(a) Low- and high-magnification images of MSC differentiation into desmin+ (brown) cells. Nuclei appear blue. The boxes in the low-magnification images (upper rows) show the location of the high-magnification images (lower rows). The migration and organization of desmin+ cells appeared to parallel those of the SMA+ cells in Figure 7a. No desmin staining was observed in EC-only modules (data not shown). Scale bars=25 μm. (b) The effect of flow and EC on MSC differentiation into desmin+ cells. The graph shows the number of desmin+ cells (bars) and the total number of cells (inset table) found within an average 10×field of the remodeling chambers' histological sections. For static cases (white bars), almost none of the cells were desmin+, independent of the presence of EC. This contrasts with flow cases (grey bars), in which EC showed a clear effect. For MSC-only flow cases, the number of desmin+ cells increased modestly over time, although this increase was not statistically significant. This modest increase contrasted with the patent increase in desmin+ cells for MSC+EC flow cases such that day 14 and 21 showed significantly more desmin+ cells than at day 7 or the corresponding static controls (p<0.05, ANOVA). Thus, flow and EC increased the number of desmin+ cells within the constructs. An increase in the total cell number accompanied the greater number of desmin+ cells for MSC+EC flow cases at day 21. The total number of cells was significantly higher than with day 21 MSC+EC static controls and MSC-only flow cases. Moreover, there was a rise in the total cell number between days 7 and 21 for MSC+EC flow cases. Similar to the SMA results, the increased number of desmin+ cells was likely caused by a combination of MSC differentiation as well as MSC proliferation followed by differentiation. (c) The effect of flow on the population of desmin+ cells. The percentage of desmin+ cells was determined as the ratio of the number of desmin+ cells to the total number of cells. For MSC-only flow cases, no statistically significant changes in the proportion of desmin+ cells were found, and desmin+ cells were in the minority. For MSC+EC constructs, there was almost no desmin+ MSC population in the static cases. With flow, the population of desmin+ cells was significantly higher than in static controls at all time points, and by day 14, the majority of cells within the remodeling chambers were desmin+. This illustrates the ability of flow and EC to guide the differentiation of MSC toward a desmin+ phenotype. Connecting lines represent a statistically significant difference between conditions (p<0.05, ANOVA), all error bars are±SEM, and the number of analyzed remodeling chambers is given in the inserted table. F, flow; S, static. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

FIG. 9.

von Kossa–stained modular constructs after 21 days at high magnification. Mineralization appears black, and nuclei appear red. No mineralization was found within the perfused or statically cultured modular constructs. Scale bars=25 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/tea

For statically cultured MSC-only modules, there were few SMA+ cells, and these were sparsely distributed throughout the construct (Fig. 7). There were virtually no desmin+ cells (Fig. 8). In the absence of EC, flow appeared to enhance the expression of SMA and desmin modestly, although not statistically significantly so. At day 21, many MSC were found in the intermodular region (the channels), and a small number of these cells were SMA+ and desmin+. The addition of EC to the MSC modules under static conditions did not cause a significant increase in the number of SMA+ and desmin+ cells, although once flow was applied to the remodeling chambers, significant increases in the total number of SMA+ and desmin+ cells were observed, as shown quantitatively in Figures 7b and 8b, respectively. These SMA+ and desmin+ cells were located in the intermodular region and appeared to surround the EC that originally coated the individual modules. After 7 days, the SMA+ cells from MSC+EC flow cases became the dominant population, in contrast with the day 7 static controls, where they remained a minority (Fig. 7c). After 14 days of flow, the desmin+ cells became the dominant cell type in MSC+EC chambers, which contrasted with the fact that they remained a minority population in corresponding static controls and MSC-only modules (Fig. 8c).

MSC+EC flow cases also had significantly more cells than static controls (Figs. 7b and 8b). Because the number of EC was not increasing with time (Fig. 5b), the increase in cell number was attributed to the growing number of SMA+ and desmin+ cells, caused by a combination of the differentiation of preexisting MSC and the proliferation of MSC, followed by their differentiation into SMC-like cells.

With respect to MSC differentiation into an osteocyte-like phenotype, no calcium mineralization was found (Fig. 9). Collectively, these results indicate that the EC and flow both help drive MSC toward a more SMC-like phenotype and that they induce these cells to migrate toward the intermodular region near the EC that are on the module surfaces.

Discussion

Modular tissue constructs containing EC and MSC were assembled and subjected to flow for up to 21 days to study the process of long-term remodeling. In particular, the differentiation of MSC into smooth muscle-like cells and their migration into a supportive pericyte position were examined.

Construct characterization, matrix, and cellularity

After 21 days, all modular constructs contracted to similar final sizes (there were no statistically significant differences among the 3 groups by ANOVA analysis). This contrasted with the static controls, in which MSC-only modules did not contract as much as the other two types (Fig. 2, p<0.05). This difference may be attributed to changes caused by the mechanical compression (see below).

Flow added a small amount of shear to the EC, but it is not clear how this affected the embedded MSC. Flow probably altered the transport of oxygen and nutrients within the construct. Under static culture conditions, diffusion would dominate mass transport into the modular construct, but in the presence of an applied fluid pressure, a convective element can emerge, under which conditions a higher rate of ECM synthesis was considered possible.24 A different flow system would be needed to determine the precise role of such convection.

MSC differentiation and phenotype

Growth factors and cytokines present in culture medium and mechanical forces influence MSC differentiation.6,25–27 It has also been shown that MSC display phenotypes consistent with different perivascular cell populations and that MSC in the bone marrow reside in the bone marrow microvasculature.28 More recently, native, noncultured perivascular cells have been shown to express MSC markers, and purified perivascular cells from skeletal muscle and nonmuscle tissues have been shown to be myogenic3 under appropriate differentiation conditions. Irrespective of their tissue origin and after long-term culture, the cells retained their myogenicity and MSC markers; migrated in a culture model of chemotaxis; and exhibited osteogenic, chondrogenic, and adipogenic potentials at the clonal level,3 leading to the conclusion that pericytes and MSC are the same.3,29 We too observed myogenic markers and migration in our MSC-containing modules.

In our system, the MSC were embedded within the modules and not directly exposed to shear. Over time, they migrated toward the surface of the modules and the intermodular region (Fig. 3). The presence of EC on the surface of modules accelerated this process, resulting in an earlier and patent increase in migration and SMC marker expression. This contrasted with MSC-only flow cases that showed only modest (and statistically insignificant) increases over time and MSC+EC static controls that showed neither migration toward module surfaces nor enhanced SMA and desmin expression at day 21. The appearance of these SMC markers and the MSC migration toward the EC-dominated intermodular regions suggest that these cells are becoming functional SMC or resuming their original pericyte position and functionality, because this behavior is similar to what occurs in vivo. Although recent reports have shown that, under normal tissue culture conditions, MSC express detectable levels of several SMC markers including SMA, desmin, and calponin,30–32 the large difference between flow cases and static controls showed a clear flow-associated upregulation in SMC markers. Furthermore, neither chondrocytes nor myofibroblasts are consistent with this staining pattern; chondrocytes and myofibroblasts express SMA but not desmin.33,34 Calcium deposits were not seen here (Fig. 9), and hence there is no evidence of osteogenesis.

The MSC migration into the intermodular region, which the confluent EC layer populated (at least originally), is suggestive of MSC integration into the vasculature. In co-culture experiments with EC monolayers, MSC integrated into the monolayers after 2 hours, and in isolated rat heart perfusions, they similarly integrated into the EC capillary walls.35 PDGF-B has been implicated in the EC-influenced recruitment and proliferation of undifferentiated MSC, whereas TGF-β has been implicated in MSC differentiation into SMC.10 The high cellularity and the large number of SMA+ and desmin+ cells within the intermodular region are indicative of greater MSC proliferation, because MSC cultured in EC-conditioned medium have been shown to increase proliferation according to bromodeoxyuridine assay.36

There may also be a relationship between this pericyte-like MSC migration and the remodeled ECM. Perhaps the flow-stimulated EC modified the MSC niche through an EC-borne alteration of the ECM milieu. It has been shown that the ECM produced by EC contains factors that support MSC differentiation into EC and SMC and that MSC-secreted agents modify these factors in turn.37

The MSC also appeared to mitigate the loss of EC under the conditions of flow. To enhance the stabilizing effect of the MSC, FGF9 may be of use. FGF9 has recently been shown to orchestrate the wrapping of SMC around newly formed vessels, which affords them long-term (≥1 years) stability.9

Although EC can modify the MSC niche and guide their differentiation towards the SMC and EC-like phenotypes, soluble factors present in the co-culture medium can have a similar effect. MSC cultured in VEGF-containing medium become CD31+, KDR+, and FLT-1+, all three of which are EC markers.19 Moreover, shear stress stimulation has been shown to induce the development of CD31, vWF, and vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin in the murine embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cell line C3H/10T1/2.38 The complete lack of vWF and CD31 membrane staining in our MSC confirmed that they did not differentiate into an EC phenotype in our hands.

EC function

Through paracrine and soluble factor signaling, MSC affect EC migration, proliferation, and survival, all of which could benefit the modular constructs in vivo. For example, MSC cultured as three-dimensional aggregates (similar to our modules) resulted in 5 to 20 times greater secretion of proangiogenic factors such as VEGF and bFGF than those cultured in monolayers; stimulated umbilical vein EC proliferation, migration, and basement membrane invasion; and promoted EC survival in vitro.39

In the remodeling chamber, the MSC appeared to delay the complete loss of EC from the module surface (Figs. 5 and 6). We have previously shown that, when modular constructs experience short-term perfusion (24 hours), EC are unable to maintain robust adherens junctions, as evidenced by a lack of VE-cadherin organization and quality, which in turn may be caused by the production of VEGF (a permeability inducing factor) and the ongoing remodeling process.2 We also showed that, when the flow channels from a modular tissue engineered construct were reproduced on a PDMS microfluidic chip (incapable of remodeling) and lined with EC, low (2.8 dyn/cm2) and high (15.6 dyn/cm2) flow rates over the course of 21 days resulted in the dismantling of VE-cadherin junctions;40 there were no MSC in this experiment. Perhaps this loss of organized VE-cadherin expression around the perimeter of the EC (caused by the flow through the irregular channels) is related to the long-term loss of EC in EC-only modular constructs. The stabilizing effect of the MSC may stem from their ability to generate anti-apoptotic signals.7 Because the MSC were able to delay EC loss, perhaps the speed with which they differentiated and their rate of migration to the intermodular region are critical parameters. It would be useful to predifferentiate the MSC into SMC and evaluate whether they can immediately stem the loss of EC.

Matrix composition may also be a factor.41 Initially, the matrix only contained type I collagen. In vivo, the basement matrix on which EC reside contains other proteins, including fibronectin, laminin, collagen IV, and elastin. Although the MSC were producing additional matrix elements (e.g., proteoglycans), the initial lack of cues from integrin binding to these additional ECM proteins may have contributed to the EC loss through anoikis.42 In the context of tumor vessels, EC in regions that lack type IV collagen and laminin basement membrane components are CD31- and have compromised barrier function.23 The similar lack of type IV collagen and laminin in our EC-only cases may have, in part, contributed to EC dysfunction and loss. On the other hand, the additional matrix produced by the MSC (Fig. 4) may have contributed to the survival of the EC.43

Response to flow field changes

Previously, we have shown that modular constructs appeared to benefit from 24 hours of perfusion;2 perfusion caused a transient increase in EC activation (intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression) after 1 hour, followed by a decrease after 24 hours. Proliferation was also significantly less, whereas Krueppel-like factor 2, which is upregulated with atheroprotective laminar shear stress, was upregulated significantly after 24 hours. In the present study, the initial flow through the constructs was laminar, but after 7 days, significant remodeling had occurred, and this certainly altered the flow field within the system; as the tissue remodeled, it compacted, leading to a significant amount of channeling around the edges of the remodeled mass.

The changing flow field may also be responsible for the cell loss in EC-only constructs. During blood vessel regression, blood flow ceases, and EC undergo apoptosis, leaving empty basement membrane sheaves or string vessels that can act as scaffolds for future capillary regrowth.44,45 Perhaps the EC underwent apoptosis as a consequence of the diminishing perfusion in remodeled constructs with reduced porosity, as they would in vessel regression.

New insights into modular tissue engineering

Remodeling is a critical and not understood determinant of the in vivo fate of tissue constructs, and this system allows us to study this process, in this case in the absence of the additional complexity provided by the host response. Co-culture and the application of flow appeared to be strong determinants of the in vitro fate of the construct, which highlighted the complexity and potential tunability of the remodeling process. Flow and EC appear to coordinate and increase the rate of MSC migration from the interior of modules toward a supportive position below the surface-attached EC. Moreover, flow appears to direct MSC differentiation toward a SMC phenotype. This implies that coupling flow, EC, and readily available MSC can produce more biologically relevant blood vessels. With additional optimization steps, long-term flow can emerge as a useful tool for the preconditioning of the vasculature. MSC within a modular construct experiencing flow increased matrix remodeling and proteoglycan production. Properly exploited, this effect can potentially boost the function of embedded cells before use, priming the construct's functional attributes. These flow-conditioned constructs may also be useful as tissue mimics for drug testing and biological assays. This is an important step toward creating “vascularized” tissue mimics for the purposes of bioassays that bridge the gap between the too-simplified in vitro and the too-complex in vivo.46

Conclusions

MSC were used with the intent of supporting the long-term survival of EC in a perfused modular assembled tissue. Flow caused the MSC to develop SMC markers (SMA and desmin) and a coordinated migration toward the EC layer. With further optimization, MSC in modules may be useful for the preformation of functional vasculature in tissue engineered constructs and tissue mimics.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (EB 001013). O.F. Khan acknowledges scholarship support from the Ontario Graduate Scholarship Program. M.D. Chamberlain acknowledges fellowship support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors also thank Elicia M. Prystay for her flow cytometry work and Chuen Lo for his expertise with animals.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.McGuigan A.P. Sefton M.V. Vascularized organoid engineered by modular assembly enables blood perfusion. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2006;103:11461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602740103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan O.F. Sefton M.V. Perfusion and characterization of an endothelial cell-seeded modular tissue engineered construct formed in a microfluidic remodeling chamber. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8254. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crisan M. Yap S. Casteilla L. Chen C.W. Corselli M. Park T.S. Andriolo G. Sun B. Zheng B. Zhang L. Norotte C. Teng P.N. Traas J. Schugar R. Deasy B.M. Badylak S. Buhring H.J. Giacobino J.P. Lazzari L. Huard J. Péault B. A perivascular origin for mesenchymal stem cells in multiple human organs. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:301. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pittenger M.F. Mackay A.M. Beck S.C. Jaiswal R.K. Douglas R. Mosca J.D. Moorman M.A. Simonetti D.W. Craig S. Marshak D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lennon D.P. Edmison J.M. Caplan A.I. Cultivation of rat marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in reduced oxygen tension: Effects on in vitro and in vivo osteochondrogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2001;187:345. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Cearbhaill E.D. Punchard M.A. Murphy M. Barry F.P. McHugh P.E. Barron V. Response of mesenchymal stem cells to the biomechanical environment of the endothelium on a flexible tubular silicone substrate. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1610. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan A.I. Dennis J.E. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1076. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Au P. Tam J. Fukumura D. Jain R.K. Bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells facilitate engineering of long-lasting functional vasculature. Blood. 2008;111:4551. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frontini M.J. Nong Z. Gros R. Drangova M. O'Neil C. Rahman M.N. Akawi O. Yin H. Ellis C.G. Pickering J.G. Fibroblast growth factor 9 delivery during angiogenesis produces durable, vasoresponsive microvessels wrapped by smooth muscle cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:421. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschi K.K. Rohovsky S.A. Beck L.H. Smith S.R. D'Amore P.A. Endothelial cells modulate the proliferation of mural cell precursors via platelet-derived growth factor-BB and heterotypic cell contact. Circ Res. 1999;84:298. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain M.D. Gupta R. Sefton M.V. Chimeric vessel tissue engineering driven by endothelialized modules in immunosuppressed Sprague-Dawley rats. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:151. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamberlain M.D. Gupta R. Sefton M.V. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells enhance chimeric vessel development driven by endothelial cell coated microtissues. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011 Oct 21; doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0393. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zervantonakis I.K. Kothapalli C.R. Chung S. Sudo R. Kamm R.D. Microfluidic devices for studying heterotypic cell-cell interactions and tissue specimen cultures under controlled microenvironments. Biomicrofluidics. 2011;5:13406. doi: 10.1063/1.3553237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung S. Sudo R. MacK P.J. Wan C.R. Vickerman V. Kamm R.D. Cell migration into scaffolds under co-culture conditions in a microfluidic platform. Lab Chip. 2009;9:269. doi: 10.1039/b807585a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lennon D.P. Caplan A.I. Isolation of rat marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp.Hematol. 2006;34:1606. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee E.J. Niklason L.E. A novel flow bioreactor for in vitro microvascularization. Tissue Eng Part C.Methods. 2010;16:1191. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cipriani P. Guiducci S. Miniati I. Cinelli M. Urbani S. Marrelli A. Dolo V. Pavan A. Saccardi R. Tyndall A. Giacomelli R. Matucci Cerinic M. Impairment of endothelial cell differentiation from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: New insight into the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:1994. doi: 10.1002/art.22698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J.W. Dunoyer-Geindre S. Serre-Beinier V. Mai G. Lambert J.F. Fish R.J. Pernod G. Buehler L. Bounameaux H. Kruithof E.K.O. Characterization of endothelial-like cells derived from human mesenchymal stem cells. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:826. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oswald J. Boxberger S. Jørgensen B. Feldmann S. Ehninger G. Bornhäuser M. Werner C. Mesenchymal stem cells can be differentiated into endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2004;22:377. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossner M. Yamada K.M. What's in a picture? The temptation of image manipulation. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:11. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes M. Introduction to Particle Technology. Second. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGuigan A.P. Sefton M.V. Design criteria for a modular tissue-engineered construct. Tissue Eng. 2007;13:1079. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.di Tomaso E. Capen D. Haskell A. Hart J. Logie J.J. Jain R.K. Mcdonald D.M. Jones R. Munn L.L. Mosaic tumor vessels: cellular basis and ultrastructure of focal regions lacking endothelial cell markers. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko S.H. Hong O.K. Kim J.W. Ahn Y.B. Song K.H. Cha B.Y. Son H.Y. Kim M.J. Jeong I.K. Yoon K.H. High glucose increases extracellular matrix production in pancreatic stellate cells by activating the renin-angiotensin system. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:343. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buschmann M.D. Gluzband Y.A. Grodzinsky A.J. Hunziker E.B. Mechanical compression modulates matrix biosynthesis in chondrocyte/agarose culture. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:1497. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.4.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kisiday J.D. Frisbie D.D. McIlwraith C.W. Grodzinsky A.J. Dynamic compression stimulates proteoglycan synthesis by mesenchymal stem cells in the absence of chondrogenic cytokines. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:2817. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao F. Chella R. Ma T. Effects of shear stress on 3-D human mesenchymal stem cell construct development in a perfusion bioreactor system: Experiments and hydrodynamic modeling. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;96:584. doi: 10.1002/bit.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi S. Gronthos S. Perivascular niche of postnatal mesenchymal stem cells in human bone marrow and dental pulp. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:696. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meirelles L.D.S. Caplan A.I. Nardi N.B. In search of the in vivo identity of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2287. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hegner B. Weber M. Dragun D. Schulze-Lohoff E. Differential regulation of smooth muscle markers in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Hypertens. 2005;23:1191. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000170382.31085.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peled A. Zipori D. Abramsky O. Ovadia H. Shezen E. Expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin in murine bone marrow stromal cells. Blood. 1991;78:304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karaoz E. Aksoy A. Ayhan S. SarIboyacI A.E. Kaymaz F. Kasap M. Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from rat bone marrow: Ultrastructural properties, differentiation potential and immunophenotypic markers. Histochem Cell Biol. 2009;132:533. doi: 10.1007/s00418-009-0629-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eyden B. The myofibroblast: An assessment of controversial issues and a definition useful in diagnosis and research. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2001;25:39. doi: 10.1080/019131201300004672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kana R. Dundr P. Tvrdik D. Necas E. Povysil C. Expression of actin isoforms in human auricular cartilage. Folia Biol (Praha) 2006;52:167. doi: 10.14712/fb2006052050167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmidt A. Ladage D. Steingen C. Brixius K. Schinköthe T. Klinz F.J. Schwinger R.H.G. Mehlhorn U. Bloch W. Mesenchymal stem cells transmigrate over the endothelial barrier. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:1179. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saleh F.A. Whyte M. Ashton P. Genever P.G. Regulation of mesenchymal stem cell activity by endothelial cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:391. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lozito T.P. Taboas J.M. Kuo C.K. Tuan R.S. Mesenchymal stem cell modification of endothelial matrix regulates their vascular differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:706. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang H. Riha G.M. Yan S. Li M. Chai H. Yang H. Yao Q. Chen C. Shear stress induces endothelial differentiation from a murine embryonic mesenchymal progenitor cell line. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1817. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000175840.90510.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Potapova I.A. Gaudette G.R. Brink P.R. Robinson R.B. Rosen M.R. Cohen I.S. Doronin S.V. Mesenchymal stem cells support migration, extracellular matrix invasion, proliferation, and survival of endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2007;25:1761. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan O.F. Sefton M.V. Endothelial cell behaviour within a microfluidic mimic of the flow channels of a modular tissue engineered construct. Biomed Microdevices. 2011;13:69. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9472-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young E.W. Wheeler A.R. Simmons C.A. Matrix-dependent adhesion of vascular and valvular endothelial cells in microfluidic channels. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1759. doi: 10.1039/b712486d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frisch S.M. Francis H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:619. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cooper T.P. Sefton M.V. Fibronectin coating of collagen modules increases in vivo HUVEC survival and vessel formation in SCID mice. Acta Biomater. 2011;7:1072. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baffert F. Le T. Sennino B. Thurston G. Kuo C.J. Hu-Lowe D. McDonald D.M. Cellular changes in normal blood capillaries undergoing regression after inhibition of VEGF signaling. Am.J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H547. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00616.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenhalgh D.G. The role of apoptosis in wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:1019. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunz-Schughart L.A. Freyer J.P. Hofstaedter F. Ebner R. The use of 3-D cultures for high-throughput screening: The multicellular spheroid model. J Biomol Screen. 2004;9:273. doi: 10.1177/1087057104265040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]