Abstract

Introduction:

The aims of this study were to validate ecological momentary assessment (EMA) as a method for measuring exposure to tobacco-related marketing and media and to use this method to provide detailed descriptive data on college students’ exposure to protobacco marketing and media.

Methods:

College students (n = 134; ages 18–24 years) recorded their exposures to protobacco marketing and media on handheld devices for 21 consecutive days. Participants also recalled exposures to various types of protobacco marketing and media at the end of the study period.

Results:

Retrospectively recalled and EMA-based estimates of protobacco marketing exposure captured different information. The correlation between retrospectively recalled and EMA-logged exposures to tobacco marketing and media was moderate (r = .37, p < .001), and EMA-logged exposures were marginally associated with the intention to smoke at the end of the study, whereas retrospective recall of exposure was not. EMA data showed that college students were exposed to protobacco marketing through multiple channels in a relatively short period: Exposures (M = 8.24, SD = 7.85) occurred primarily in the afternoon (42%), on weekends (35%), and at point-of-purchase locations (68%) or in movies/TV (20%), and exposures to Marlboro, Newport, and Camel represented 56% of all exposures combined and 70% of branded exposures.

Conclusions:

Findings support the validity of EMA as a method for capturing detailed information about youth exposure to protobacco marketing and media that are not captured through other existing methods. Such data have the potential to highlight areas for policy change and prevention in order to reduce the impact of tobacco marketing on youth.

Introduction

Exposure to cigarette advertising and smoking in movies and on television promotes smoking initiation and progression to regular smoking (DiFranza et al., 2006; National Cancer Institute, 2008; Wellman, Sugarman, DiFranza, & Winickoff, 2006). Measures of exposure to protobacco marketing and media have varied greatly across studies (DiFranza et al., 2006; Unger, Cruz, Schuster, Flora, & Johnson, 2001). Typically, researchers ask youth to estimate how frequently they have seen cigarette advertisements or promotions either in general or through specific channels, such as magazines or in stores (e.g., Arnett & Terhanian, 1998; Schooler, Feighery, & Flora, 1996; Weiss et al., 2006). Responses to these measures correlate with a variety of smoking-related outcomes in ways that are consistent with theory on media and advertising effects (DiFranza et al., 2006). However, a key shortcoming of such measures is that they rely on respondents’ ability to recall all the advertisements they have seen and then accurately estimate how often they have been exposed to them (Unger et al., 2001). There is considerable evidence to suggest that global self-reports of exposure to advertising are biased by faulty or inaccurate memory and concerns about providing socially desirable responses (Bradburn, 2000; Hammersley, 1994; Schwarz & Oyserman, 2001). Moreover, low correlations between retrospective recall measures and more objective indices of exposure suggest that memories capture something other than mere exposure to tobacco marketing and portrayals (Feighery, Henriksen, Wang, Schleicher, & Fortmann, 2006; Unger et al., 2001).

Other commonly used measures of exposure include awareness of marketing (e.g., ability to name a brand), appreciation of advertisements (e.g., naming a favorite advertisement), ownership of or willingness to use a tobacco company promotional item, or a scale of receptivity to marketing that combines aspects of other measures (Unger et al., 2001). These measures are limited in that they capture exposure to protobacco marketing and media only indirectly and likely assess more than mere exposure and comprehension. For example, receptivity measures appear to involve cognitive and affective appraisals of advertising in addition to exposure and comprehension (Unger et al., 2001). Therefore, while these measures may effectively capture exposure to advertisements and media portrayals that are persuasive and memorable, they likely underestimate youths’ total amount of protobacco marketing exposure.

Even measures that capture data on exposure more objectively, such as those used in recent studies of tobacco portrayals in movies (e.g., Sargent et al., 2005) and exposure to point-of purchase (POP) promotion (e.g., Henriksen, Schleicher, Feighery, & Fortmann, 2010), are not without limitation. For example, studies that ask youth about whether they have seen specific popular movies and link this information to objective data from content analyses of those same movies are limited in scope as they only ask about a subset of popular movies and they do not capture movies (newer and older) that adolescents may be watching on television, via rentals, or on the Internet. Likewise, studies that quantify the number of marketing materials in particular convenience and grocery stores and frequency of exposure at these stores may not capture all stores that youth visit nor whether or not youth notice the tobacco marketing in the stores that are sampled.

There is also concern that current measures focus on a narrow range of exposures, thus failing to account fully for the broad and diverse ways through which youth are exposed to protobacco media messages. As regulatory activities in the last fifteen years have sharply curtailed tobacco advertising in traditional venues (e.g., restricting magazine advertising), POP promotion has become the dominant medium for tobacco advertising, representing 81% of the tobacco industry’s total marketing expenditures in 2006 (Federal Trade Commission [FTC], 2009; Wakefield et al., 2002). Nevertheless, youth continue to be exposed to magazine advertisements, particularly for brands that appeal most to youth (i.e., Marlboro, Camel, and Newport; O’Connor, 2005). Similarly, nearly half of popular movies still contain tobacco imagery (Glantz, Titus, Mitchell, Polansky, & Kaufmann, 2010). Smoking is also portrayed in nearly one fourth of all music videos (Durant et al., 1997), 19% of prime-time television shows (Christenson, Henriksen, & Roberts, 2000), and 24% of popular songs (Primack, Dalton, Carroll, Agarwal, & Fine, 2008). Many websites sell tobacco products, and few employ effective age verification procedures (Jenssen, Kleinn, Salazar, Daluga, & DiClemente, 2009). Youth are also exposed to tobacco imagery through online videos and social networking sites (Moreno, Parks, Zimmerman, Brito, & Christakis, 2009), and these emerging technologies provide new opportunities for exposure to tobacco advertising (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2010). All these channels work together to promote cigarette use; considering only some of them may mischaracterize the extent to which youth are exposed to protobacco marketing and media.

In this complex rapidly shifting marketing environment and media landscape, there is an urgent need to develop measurement approaches that more precisely capture total exposure to tobacco promotion and its effects. Detailed information on exposure is essential for understanding the mechanisms responsible for observed links between tobacco promotion and youth smoking and to develop effective tobacco use prevention programs. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is a method of real-time data collection that has significant potential to provide detailed information on exposure to tobacco advertising. Though based on participant’s self-report, EMA data are collected in “real time,” at the moment when participants are exposed to a stimulus or engaged in an activity (Shiffman, Stone, & Hufford, 2008). EMA can provide ecologically valid information about the mix of protobacco media messages to which youth are exposed, a breakdown of intensity of exposure to different marketing and media channels, and allow a detailed analysis of the types of messages targeted at different segments of the population. Because EMA consists of frequent repeated measurements, it provides a movie-like view of processes rather than the static snapshot provided by a cross-sectional design or the few infrequent snapshots provided by a prospective design. EMA can also minimize recall bias by having participants record their exposures at or near the time that they occur. Although EMA has been used successfully in several areas (e.g., in studies of binge eating and cigarette smoking; Haedt-Matt & Keel, 2010; Shiffman, Kirchner, Ferguson, & Scharf, 2009), it has never before been used to study exposure to protobacco marketing and media.

In the current study, we adapted EMA methods to assess exposure to protobacco marketing and media in college students. College students are an important population among which to investigate exposure to protobacco marketing and media. Although the majority (59%) of initial smoking occurs prior to age 18 years (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2010), a significant proportion of initial and experimental smoking happens during the college years. The tobacco industry recognizes this age group as a significant target market and has shifted their marketing focus away from younger adolescents toward young adults (Ling & Glantz, 2002). Nevertheless, few studies have examined college students’ exposure to tobacco marketing and media; thus, very little is known about the extent or effects of exposure in this group. This paper attempts to narrow that gap by providing detailed descriptive data on college students’ exposure to protobacco marketing and media and demonstrating the utility of EMA as a way to capture ecologically valid information about the entire mix of tobacco-related media and advertising to which college-aged youth are exposed.

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through advertisements in university and other local newspapers. Two hundred and twenty-four students from three colleges located in a single urban area were screened for the study, 150 of whom met inclusion criteria: undergraduate students between the ages of 18 and 24 years. Of those invited to participate, 142 (90%) attended the baseline session. Three individuals dropped out or were dismissed from the study because they failed to comply with the EMA protocol. Data from four participants were lost due to software malfunction. We also removed data from one individual whose responses were several SDs beyond the mean. Thus, the analytic sample consisted of 134 individuals (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Sample Characteristics (N = 134)

| Respondent characteristic | M (SD) or % |

| Age, years (M, SD) | 20.93 (1.55) |

| Female (%) | 63 |

| Race (%) | |

| Black | 25 |

| Asian American | 4 |

| Caucasian | 65 |

| Other | 6 |

| Number of semesters of college completed (M, SD) | 4.60 (2.60) |

| Living arrangement (%) | |

| Dormitory | 19 |

| Fraternity/sorority house or school-owned apartment | 9 |

| Off-campus apartment | 43 |

| Off-campus with family or other relatives | 29 |

| Average number of hours worked per week (%) | |

| Not working | 37 |

| Less than 10 | 19 |

| 11–20 | 24 |

| 21–40 | 17 |

| More than 40 | 3 |

| Smoking statusa (%) | |

| Never-smoker | 39 |

| Experimental smokers | 52 |

| Nonestablished regular smokers | 9 |

Note. aNever-smokers reported never smoking a cigarette, even a puff. Experimental smokers reported smoking in the past but not the past month. Nonestablished regular smokers smoked on an average of 6 days (SD = 4.4) in the past month and smoked an average of 2.2 (SD = 1.3) cigarettes on the days that they smoked.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by the RAND Human Subjects Protection Committee. Data collection took place from June 2010 to January 2011. At baseline, participants provided informed consent and completed a survey with questions about demographics, smoking history, and their thoughts and feelings about smoking; they were also trained to use the handheld devices to record information about their exposure to protobacco marketing and media. Participants then used the devices to record their exposures to cigarette advertising for 21 consecutive days. During the study period, participants attended in-person weekly sessions during which they had their data from the previous week uploaded to a central database. At the end of the study, they attended a final session during which their final week’s data were uploaded, and they completed an end-of-study survey.

Participant training consisted of a 60-min oral presentation accompanied by electronic slides. A data collection device was provided to each participant at the start of the training, so they could practice data entry during the presentation (these entries were subsequently deleted). Participants were instructed to turn the device on when they woke in the morning and off at night when they went to sleep, carry the device with them at all times, and initiate data entry each time they encountered protobacco marketing or media.

Our definition of protobacco marketing and media partly reflected the FTC’s (2009) definitions of media advertising, promotional materials, and sponsorships by the tobacco industry. “Media advertising” included magazines, outdoor advertising (including billboards, placards in stadiums and shopping malls, and any other advertisements placed outdoors), retailer POP advertising, and advertisements placed in adult-oriented venues, such as bars. “Promotional materials” included direct-to-consumer coupons and general consumer mailings, as well as advertised discounts at POP (e.g., a two-for-one special on cigarette packs). “Sponsorships” included tobacco company support of concerts or sports events and support of individual athletes and musicians/actors. Although the tobacco industry denies product placement in films and television programs, these media are important means through which adolescents are exposed to cigarettes and smoking (Wellman et al., 2006). Thus, we also assessed exposure to smoking in movies and television programs. Finally, we assessed exposure to advertising on the Internet at tobacco company websites and through banner advertising and portrayal of smoking on social networking and video-viewing websites. Participants were shown (via slide show) multiple examples of each form of promotion during training. Training materials were developed and refined during a formative phase of the research, which included focus group feedback on the training and study protocol.

Participants answered questions about their smoking-related beliefs, feelings, and intentions after recording exposures to protobacco advertising and after three random prompts per day. This type of EMA design in which information is collected at random prompts to provide a baseline against which to compare data collected following “event-based” recordings has been used in several other domains. For example, Hedeker, Mermelstein, Berbaum, and Campbell (2009) used this type of EMA design to examine smokers’ mood following episodes of smoking versus at random moments at nonsmoking. We do not, however, report on data from the random prompts in this paper nor do we report on questions about participants’ thoughts and feelings about smoking; those data are reported elsewhere (Shadel, Martino, Setodji, & Scharf, 2010).

Participants were paid $8 for each day of EMA assessment and $10 each for completing the baseline and end-of-study surveys. They were paid an additional $2 per day if they responded to all random prompts on that day within 2 min of the prompt. Thus, participants could be paid up to $230 if they completed all facets of the study.

Handheld Data Collection Devices and Software

Data were collected on Palm Treo 755p smart phones. These devices ran the Palm OS Garnet v. 5.4.9 and used a 312 MHz Intel PXA270 processor. Data could be entered either via touch screen or using a stylus. The Pendragron 5.1 forms application (Pendragon Software Corporation, 2010) was programmed to administer the measures described below at moments of exposure and at random prompts.

Measures

This list of measures includes only those analyzed and reported in this paper.

Background Information

At baseline, participants reported basic demographic information and past experience with and current level of smoking.

EMA-Based Exposure to Protobacco Marketing and Media

During the 21-day EMA period, participants provided descriptive information about each encounter with protobacco marketing and media, including the medium of exposure using a forced-choice response format: in a magazine, on a billboard, outside of a convenience store or gas station, inside a grocery store, inside or on the window of a convenience store or gas station, in a tobacco store, in a bar or restaurant (including being approached by a salesperson in these venues), via direct mailing or coupon, at a sponsored event, in a movie, on television, on the radio, and on the Internet. Participants also indicated the brand or brands that were advertised or portrayed (if apparent).

Retrospective Recall of Exposure to Protobacco Marketing and Media

At the end of the study, participants recalled how often they were exposed to the various types of protobacco marketing and media over the past thirty days using the following questions derived from national tobacco surveys (e.g., the Youth Tobacco Surveillance Survey): During the past 30 days, about how many times have you (a) seen cigarette advertisements in magazines, (b) seen advertisements for cigarettes on billboards or outdoor signs, (c) seen advertisements for cigarettes in convenience stores or grocery stores, (d) seen someone in a bar or pub giving away free cigarettes, (e) seen someone smoking in movies, (f) seen someone smoking on television, and (g) seen advertisements for cigarettes while on the internet? Questions were answered on a 6-point scale with these response options: never (1), 1–2 times (2), 3–4 times (3), 5–10 times (4), 11–20 times (5), and more than 20 times (6). We chose to retain the timeframe of these standard items even though it created a discrepancy between the timeframe of the EMA (21 days) and the timeframe for retrospective recall (30 days). This discrepancy has no bearing on the association between EMA-based estimates and retrospective recall of exposure or the comparative predictive utility of these two measures. We averaged responses to these seven items to create a measure of retrospective recall of exposure to protobacco marketing and media (α = .69).

Smoking Intentions

At the end-of-study survey, participants indicated their future intentions to smoke by completing a three-item scale adapted from Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, and Pierce (2001) and shown to be predictive of smoking initiation. The items are, “Do you think you will try a cigarette anytime soon,” “Do you think you will smoke a cigarette anytime in the next year,” and “If one of your best friends offered you a cigarette, would you smoke it?” Responses were made on a 1 (Definitely not) to 10 (Definitely yes) scale and averaged to create a measure of intention to smoke (α = .94). Following standard practice, we dichotomized this measure such that youth who had anything but a firm commitment not to smoke (i.e., a score >1.00) were considered at risk for future smoking (Pierce, Choi, Gilpin, Farkas, & Merritt, 1996).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample on several demographic characteristics and on current smoking status. Ever-smokers comprised 61% of our sample; of those, 85% (n = 70) were experimental smokers who had not smoked in the past month and 15% (n = 13) were nonestablished regular smokers who smoked on 6 days (SD = 4.4) in the past month and smoked an average of 2.2 cigarettes (SD = 1.3) on the days that they smoked.

Validity of EMA as a Measure of Exposure to Tobacco Advertising and Media

The zero-order correlation between participants’ retrospective recall and EMA-based measure of exposure was .37. Thus, less than 14% of the variation in the EMA-based measure of exposure was explained by the retrospective recall measure. To further characterize the association between retrospective recall and EMA, we grouped participants into low, medium, and high tertiles on the retrospective recall and EMA-based measures of exposure and then cross-tabulated these two categorical (low–medium–high) indices. Fifty-eight percent of participants were classified in different groups by the two measures; among those, 26% were classified into extreme opposite categories (e.g., participants classified as low exposure on the basis of retrospective recall were classified as high exposure based on EMA). Thus, retrospective recall and EMA appeared to measure different aspects of exposure to tobacco advertising and media.

To compare the predictive validity of the EMA and retrospective recall measures of exposure to protobacco marketing and media, we used separate logistic regression models to estimate the association between amount of exposure and participants’ intention to smoke at the end of study. To control for the potential of smoker status to confound this association and to test whether exposure to protobacco marketing and media is associated with the intention to smoke differently among never- versus ever-smokers, we included as predictors in each of these regression models an indicator of smoker status and an interaction between smoker status and exposure. Because all nonestablished regular smokers (n = 13) in our sample reported an intention to smoke, we could not include them in this analysis. Thus, the smoker status variable employed in these analyses was simply a dichotomous indicator that compared never-smokers with experimental smokers.

The top of Table 2 presents the results of the model that included the EMA-based measure of exposure to protobacco marketing and media; the bottom of Table 2 presents the results of the model that included the measure of exposure based on retrospective recall. In each of these models, the coefficients for the exposure variable quantify the association between exposure and intention to smoke among experimental smokers; the interaction tests whether that association differs among never-smokers. In the analysis that employed the EMA-based measure of exposure to predict intention to smoke, number of exposures to protobacco marketing and media was marginally associated with the intention to smoke among experimental smokers, odds ratio (OR) = 1.083, p = .097. The nonsignificant (p = .41) interaction term suggests that this association is also present among never-smokers. In the analysis that employed the measure of exposure based on retrospective recall, number of exposures to protobacco marketing and media was not associated with the intention to smoke among experimental smokers (OR = 0.789, p = .52), and the nonsignificant (p = .32) interaction term suggests that the same was true among never-smokers. Together these analyses suggest that exposure captured via EMA may be a better predictor of intention to smoke than retrospectively recalled exposure.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Analyses Predicting Any Intention to Smoke From Smoking Status, Exposure to Protobacco Marketing and Media, and Their Interaction (N = 121)

| Predictor | Odds ratio | β | SE | p Value |

| Analysis with ecological momentary assessment–based measure of exposure | ||||

| Never-smokera | 0.085 | −2.461 | 1.080 | .023 |

| Exposure | 1.083 | 0.079 | 0.048 | .097 |

| Never-smoker × Exposure | 0.899 | −0.106 | 0.129 | .410 |

| Analysis with retrospective recall of exposure | ||||

| Never-smokera | 0.015 | −4.191 | 1.300 | .015 |

| Exposure | 0.789 | −0.237 | 0.369 | .521 |

| Never-smoker × Exposure | 2.772 | 1.019 | 1.020 | .318 |

Note. aVersus experimental smoker.

Descriptive Data on Exposure as Measured by EMA

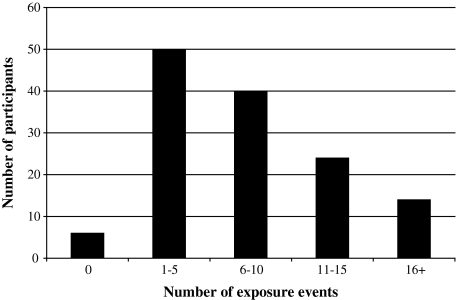

Across the 21-day EMA-monitoring period, participants reported an average of 8.24 (SD = 7.85) exposures to protobacco marketing and media. Figure 1 shows the number of participants reporting different numbers of exposure events during this period. Across all participants, there were 1,112 exposure events captured by EMA. Twenty-one percent of these involved advertising or promotion for more than one cigarette brand. Mean number of exposures did not differ between never-smokers (M = 7.90, SD = 5.89) and ever-smokers (M = 7.75, SD = 6.20). Similarly, there were no differences in exposures by gender or race, Fs < 1, and no correlation between age and number of exposures, r = .14, p = .12.

Figure 1.

Number of participants reporting different numbers of exposure events during the 21-day ecological momentary assessment period.

Table 3 shows the number of exposure events that occurred on each day of the week and the times of day at which exposures occurred. Afternoon (12–6 p.m.) was the time of day on which the largest proportion (42%) of exposures occurred, followed by evening (6 p.m.–12 a.m., 32%), morning (6 a.m.–12 p.m., 19%), and night (12–6 a.m., 8%). Thirty-five percent of all exposures occurred on weekends (Friday and Saturday), while exposures on the other 5 days of the week were relatively constant (12%–14% per day).

Table 3.

Number of Exposure Events Occurring on Each Day of the Week by Time of Day

| Day of week |

||||||||

| Time of day | Sunday | Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Total |

| 6 a.m.–12 p.m. | 21 | 27 | 41 | 18 | 26 | 45 | 30 | 208 |

| 12 p.m.–6 p.m. | 55 | 63 | 56 | 57 | 66 | 96 | 69 | 462 |

| 6 p.m.–12 a.m. | 43 | 47 | 54 | 42 | 49 | 58 | 63 | 356 |

| 12 a.m.–6 a.m. | 11 | 16 | 12 | 12 | 8 | 9 | 18 | 86 |

| Total | 130 | 153 | 163 | 129 | 149 | 208 | 180 | 1,112 |

Table 4 shows the number and proportion of encounters to protobacco marketing and media through each channel of promotion. Approximately two thirds of exposure events occurred at POP. Approximately 20% of exposures were to portrayals of smoking on television or in movies. Exposures to magazine advertisements and Internet sites each accounted for only 3%–4% of exposure events.

Table 4.

Number and Proportion of Encounters to Protobacco Marketing and Media That Occurred Through Each Mode of Promotion

| Mode of encounter | Number of encounters | % of encounters |

| Point of purchase | ||

| In a convenience store | 368 | 33 |

| Outside: store/gas station | 165 | 15 |

| Window: store/gas station | 116 | 10 |

| In a grocery store | 71 | 6 |

| In a tobacco store | 11 | 1 |

| On television | 116 | 10 |

| In a movie | 100 | 9 |

| In a magazine | 40 | 4 |

| In a bar/restaurant | 38 | 3 |

| On the Internet | 38 | 3 |

| On a billboard | 26 | 2 |

| Direct mail/coupon | 13 | 1 |

| On the radio | 3 | <1 |

| Sponsored event | 2 | <1 |

| Approached by salesperson | 1 | <1 |

Table 5 shows the cigarette brands to which participants were exposed. The brands to which youth were most commonly exposed are the three most popular brands among youth in the United States: Marlboro, Newport, and Camel. Exposure to these three brands represents 56% of total exposures (70% of branded exposures). Other commonly encountered brands included Wave (5% of total exposures and 6% of branded exposures), Kool (3% each of total and branded exposures), Maverick (3% each of total and branded exposures), and American Spirit (3% each of total and branded exposures). Brand was not apparent in 15% of exposures, most of which (90%) involved exposures on television or in movies. Participants named the brand of cigarette in 52 of the 219 (24%) television and movies exposures, and in all but five cases, they named Marlboro, Newport, or Camel as the brand of cigarette portrayed.

Table 5.

Cigarette Brands (grouped by manufacturer) to Which 134 Participants Were Exposed During 1,112 Exposure Events

| Manufacturer/brand | Number of exposures | Percent of branded exposures |

| Philip Morris USA | ||

| Marlboro | 385 | 32.0 |

| Basic | 17 | 1.4 |

| L&M | 13 | 1.1 |

| Other (4 brands) | 20 | 1.7 |

| Lorillard Tobacco Company | ||

| Newport | 278 | 23.1 |

| Maverick | 40 | 3.3 |

| Kent | 2 | 0.2 |

| RJ Reynolds | ||

| Camel | 176 | 14.6 |

| Kool | 41 | 3.4 |

| Pall Mall | 23 | 1.9 |

| Other (7 brands) | 41 | 3.4 |

| Japan Tobacco International | ||

| Wave | 68 | 5.7 |

| Wings | 10 | 0.8 |

| Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company | ||

| American Spirit | 38 | 3.2 |

| Liggett Group Inc. | ||

| Silver Eagle | 23 | 1.9 |

| Pyramid | 2 | 0.2 |

| Commonwealth Brands Inc. | ||

| USA Gold | 15 | 1.2 |

| Cigarette brands from other manufacturers (4) | 10 | 0.8 |

| Brand not apparent to respondent | 163 | – |

| Cigarette brand(s) unspecifieda | 31 | – |

| Nonbranded advertisingb | 22 | – |

| Otherc | 74 | – |

| Total | 1,493 |

Note. aRespondents simply responded “wall of cigarettes” or “all brands of cigarettes.”

Typically, advertisements for “cigarettes” or “discounted cigarettes” in general.

Includes seven advertisements for e-cigarettes, 24 for cigars/cigarillos, and 43 missing or ambiguous responses.

Discussion

Each year, the tobacco industry spends billions of dollars promoting cigarettes. Despite impressive evidence linking exposure to protobacco marketing and media to youth smoking (Charlesworth & Glantz, 2005; Wellman et al., 2006), precise data on youth exposure have been lacking in part because of the limitations of existing measures. This study is the first to employ EMA to investigate where, when, and how often youth encounter protobacco marketing and media. The moderate correlation between retrospectively recalled and EMA-based estimates of exposure suggests that these measures capture different information. Stronger association between EMA-based measure of exposure and intention to smoke suggests that this difference is important and that use of this method is worthwhile beyond the detailed descriptive data it provides.

Using this new method, we show that college students report a significant amount of exposure to protobacco marketing and media through a variety of channels in a relatively short period. If the rate of exposure we observed over 3 weeks remained constant, youth would experience an estimated 143 exposure events annually. In a separate investigation that used the EMA data reported here to examine momentary fluctuations in cigarette attitudes and intentions in response to exposure to protobacco marketing and media, we found that just a single exposure shifts youths’ attitudes and intentions toward smoking (Shadel et al., 2010). Thus, the cumulative effect of 100+ exposures annually is likely to make a significant and lasting impact on their thoughts and feelings about smoking and on their actual smoking behavior.

The large majority of exposures that we captured are through POP promotions. This is consistent with the fact that the vast majority of advertising expenditures (81% in 2006; FTC, 2009) is dedicated to POP. Compared with smoking in movies and magazine advertising, POP promotion has received little attention in the literature on protobacco marketing and media. Studies that have examined this mode of promotion have shown that cigarettes are marketed more heavily in stores where adolescents shop (Henriksen, Feighery, Schleicher, Haladjian, & Fortmann, 2004) and that youth who are exposed to POP promotion have inflated perceptions of the availability and popularity of tobacco (Henriksen, Flora, Feighery, & Fortmann, 2002). Taken together, our research suggests that POP should be a prime focus of policy and prevention efforts to reduce the impact of tobacco marketing on youth.

Television and movie exposures represent a sizeable minority of the exposures that we observed. Such exposures are thought to be particularly impactful, given that youth tend not to consider their persuasive appeal and thus are unlikely to be skeptical of them (Dal Cin, Zanna, & Fong, 2004; Slater, 2002). Though a recent focus of the literature has been on smoking in movies, our study makes clear that television is also a significant source of tobacco portrayals. It is noteworthy that participants could identify the brand of cigarette smoked in 24% of the movie and television portrayals. Our data closely coincide with the results of a content analysis of popular films from 1988 to 1997, which found that most (85%) films contained some tobacco use and that there were specific brand appearances in 28% of the total film sample (Sargent et al., 2001). Thus, portrayal of specific brands in movies continues despite the Master Settlement Agreement ban on payments by the tobacco industry to promote tobacco products in movies and television shows.

Although youth were exposed to few tobacco advertisements or portrayals of smoking through the Internet, we suspect that this may change as tobacco companies take greater advantage of this medium as a source of promotion. Little is known about the effects of portrayals of smoking through social media, such as social networking and online video; however, there is reason to believe that such exposures may be especially potent considering the increased potential for peer mediation of the effects of exposure (Moreno et al., 2009).

Our study provides initial evidence for the utility of EMA for capturing detailed ecologically valid data on exposure to a wide range of protobacco marketing and media. The ability to do so in a tobacco marketing environment that is constantly shifting is crucial for understanding the myriad ways in which youth are exposed to and potentially affected by protobacco marketing and media. The validity of our EMA-based measure of exposure to protobacco marketing and media is supported by the fact that the brands to which participants were exposed most frequently and the channels through which they were commonly exposed fit with data on advertising expenditures (FTC, 2009), the rate of cigarette brand appearances in popular movies (Sargent et al., 2001), and the targeting of youth by the tobacco industry (Chung et al., 2002). The validity of this measure is also supported by its association with youths’ intentions to smoke; however, this finding should be interpreted cautiously as the association was only marginally significant. Moreover, this association should not be interpreted as causal. Although it is plausible that exposure to protobacco marketing and media in this study contributed to participants’ intentions to smoke, it is also plausible that participants who had an intention to smoke at the outset of the study sought environments with more protobacco marketing and media during the EMA period than did participants without intentions to smoke. The correlational data presented here do not support one of these interpretations over the other nor do they rule out the possibility that some third variable is responsible for the relationship. We present this association only as evidence of the validity of our method.

Reactivity has not been shown to be a concern with EMA (Shiffman, 2009); however, without a completely objective measure of exposure to protobacco marketing and media by which to calibrate our EMA-based measure, we cannot rule out the possibility that our results were influenced by participants’ perceptions, attitudes, or related psychological constructs. That is, although EMA-based measures of the events to which people are exposed in their natural environments are subject to less bias than recall-based measures of those same events, neither is a purely objective measure of exposure. It is possible, for example, that youth report only those exposures to which they pay a certain amount of attention or that are particularly salient to them (perhaps as a function of prior exposures). It is also possible that some of youths’ perceptions of specific brands of cigarettes in the television shows and movies that they watch are biased by youths’ assumptions and past experiences with those brands. In future studies, it will be important to collect more objective data on exposure (e.g., having researchers code the television shows and movies in which youth report seeing smoking or visit the stores and other locations at which youth report seeing POP advertising) with which to validate the EMA-based measure of exposure introduced here.

Our study is also limited in that it uses a reactively recruited sample of college students and incorporates only one period of EMA assessment. That we focus on college students is, on the one hand, a strength of our study; little is known about the extent and effects of exposure to protobacco marketing and media among college-aged youth despite manufacturers’ increasing efforts to reach them. On the other hand, college students (even ones residing in urban areas) may be more insulated from protobacco marketing and media than other similarly aged youth. In future work, it will be important to replicate this design with adolescents and young adults who are not in school to see if the patterns of exposure (amount and distribution by type) seen in this study are replicated in other samples of youth. Despite these limitations, this study represents a significant step forward in the measurement of exposure to protobacco marketing and media and provides a wealth of uniquely informative data on such exposure among college-aged youth.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA1237286 to WGS).

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Jill Schaefer, Justin Greenfield, and Michelle Horner for their invaluable assistance in executing the procedures of this research.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement—Media education. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1012–1017. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1636. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Terhanian G. Adolescents’ responses to cigarette advertisements: Links between exposure, liking, and the appeal of smoking. Tobacco Control. 1998;7:129–133. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.2.129. doi:10.1136/tc.7.2.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradburn NM. Temporal representation and event dating. In: Stone AA, Turkkan JS, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman HS, Cain VS, editors. The science of self-report: Implications for research and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 49–61. [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: A review. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1516–1528. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0141. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96:313–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96231315.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96231315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson PG, Henriksen L, Roberts DF. Substance use in popular prime-time television. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Policy Control; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chung PJ, Garfield CF, Rathouz PJ, Lauderdale DS, Best D, Lantos J. Youth targeting by tobacco manufacturers since the Master Settlement Agreement. Health Affairs. 2002;21:254–263. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.254. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Cin S, Zanna MP, Fong GT. Narrative persuasion and overcoming resistance. In: Knowles ES, Linn JA, editors. Resistance and persuasion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- DiFranza JR, Wellman RJ, Sargent JD, Weitzman M, Hipple BJ, Winickoff JP. Tobacco promotion and the initiation of tobacco use: Assessing the evidence for causality. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1237–e1248. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1817. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant RH, Rome ES, Rich M, Allred E, Emans SJ, Woods ER. Tobacco and alcohol use behaviors portrayed in music videos: A content analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1131–1135. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1131. doi:10.2105/AJPH.87.7.1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Trade Commission. Cigarette report for 2006. Washington, DC: Author; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Feighery EC, Henriksen L, Wang Y, Schleicher NC, Fortmann SP. An evaluation of four measures of adolescents’ exposure to cigarette marketing in stores. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:751–759. doi: 10.1080/14622200601004125. doi:10.1080/14622200601004125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glantz SA, Titus K, Mitchell S, Polansky J, Kaufmann RB. Smoking in top-grossing movies—United States, 1991–2009. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59:1014–1017. Retieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/sk/mm5932.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Hunger and binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010 doi: 10.1002/eat.20868. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/eat.20868/pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammersley R. A digest of memory phenomena for addiction research. Addiction. 1994;89:283–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00890.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ, Berbaum ML, Campbell RT. Modeling mood variation associated with smoking: An application of a heterogeneous mixed-effects model for analysis of Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) data. Addiction. 2009;104:297–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02435.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Feighery E, Schleicher NC, Haladjian H, Fortmann SP. Reaching youth at the point of sale: Cigarette marketing is more prevalent in stores where adolescents shop frequently. Tobacco Control. 2004;13:315–318. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006577. doi:10.1136/tc.2003.006577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Flora JA, Feighery E, Fortmann SP. Effects on youth of exposure to retail tobacco advertising. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:1771–1789. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00258.x. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126:232–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenssen BP, Kleinn JD, Salazar LF, Daluga NA, DiClemente RJ. Exposure to tobacco on the Internet: Content analysis of adolescents’ Internet use. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e180–e186. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-3838. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. doi:10.2105/AJPH.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno M, Parks M, Zimmerman F, Brito TE, Christakis DA. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and associations. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:27–34. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. (NIH Publication No. 07–6242) [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RJ. What brands are U.S. smokers under 25 choosing? Tobacco Control. 2005;14:213–215. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.010736. doi:10.1136/tc.2004.010736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendragon Software Corporation. 2010 Pendragon Forms 5.1 [software]. Retrieved from http://pendragonsoftware.com. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Merritt RK. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychology. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack BA, Dalton MA, Carroll MV, Agarwal AA, Fine MJ. Content analysis of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs in popular music. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:169–175. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, Gibson JJ, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Carusi CP, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: Its relation to smoking initiation among U.S. adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1183–1191. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Tickle JJ, Beach ML, Dalton MA, Ahrens MB, Heatherton TF. Brand appearances in contemporary cinema films and contribution to global marketing of cigarettes. Lancet. 2001;357:29–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03568-6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03568-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooler C, Feighery R, Flora JA. Seventh graders’ self-reported exposure to cigarette marketing and its relationship to their smoking behavior. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1216–1221. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.9.1216. doi:10.2105/AJPH.86.9.1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz N, Oyserman D. Asking questions about behavior: Cognition, communication, and questionnaire construction. American Journal of Evaluation. 2001;22:127–160. doi:10.1177/109821400102200202. [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Martino SC, Setodji CM, Scharf DM. Momentary effects of pro-tobacco media exposure on college students’ thoughts about smoking. 2010 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:486–497. doi: 10.1037/a0017074. doi:10.1037/a0017074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Kirchner TR, Ferguson SG, Scharf DM. Patterns of intermittent smoking: An analysis using ecological momentary assessment. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:514–519. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.004. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater MD. Entertainment education and the persuasive impact of narratives. In: Green MC, Strange JJ, Brock TC, editors. Narrative impact: Social and cognitive foundations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2002. pp. 157–181. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2009 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Volume I. Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Cruz TB, Schuster D, Flora JA, Johnson CA. Measuring exposure to pro- and anti-tobacco marketing among adolescents: Intercorrelations among measures and associations with smoking status. Journal of Health Communication. 2001;6:11–29. doi: 10.1080/10810730150501387. doi:10.1080/10810730150501387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield MA, Terry-McElrath YM, Chaloupka FJ, Barker DC, Slater SJ, Clark PI, et al. Tobacco industry marketing at point of purchase after the 1998 MSA billboard advertising ban. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:937–940. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.937. doi:10.2105/AJPH.92.6.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JW, Cen S, Schuster DV, Unger JB, Johnson CA, Mouttapa M, et al. Longitudinal effects of pro-tobacco and anti-tobacco messages on adolescent smoking susceptibility. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:455–465. doi: 10.1080/14622200600670454. doi:10.1080/14622200600670454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman R, Sugarman D, DiFranza J, Winickoff JP. The extent to which tobacco marketing and tobacco use in films contribute to children's use of tobacco: A meta-analysis. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:1285–1296. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1285. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.12.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]