Abstract

ATP7A is a P-type ATPase that regulates cellular copper homeostasis by activity at the trans-Golgi network (TGN) and plasma membrane (PM), with the location normally governed by intracellular copper concentration. Defects in ATP7A lead to Menkes disease or its milder variant, occipital horn syndrome or to a newly discovered condition, ATP7A-related distal motor neuropathy (DMN), for which the precise pathophysiology has been obscure. We investigated two ATP7A motor neuropathy mutations (T994I, P1386S) previously associated with abnormal intracellular trafficking. In the patients' fibroblasts, total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy indicated a shift in steady-state equilibrium of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S, with exaggerated PM localization. Transfection of Hek293T cells and NSC-34 motor neurons with the mutant alleles tagged with the Venus fluorescent protein also revealed excess PM localization. Endocytic retrieval of the mutant alleles from the PM to the TGN was impaired. Immunoprecipitation assays revealed an abnormal interaction between ATP7AT994I and p97/VCP, an ubiquitin-selective chaperone which is mutated in two autosomal dominant forms of motor neuron disease: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and inclusion body myopathy with early-onset Paget disease and fronto-temporal dementia. Small-interfering RNA (SiRNA) knockdown of p97/VCP corrected ATP7AT994I mislocalization. Flow cytometry documented that non-permeabilized ATP7AP1386S fibroblasts bound a carboxyl-terminal ATP7A antibody, consistent with relocation of the ATP7A di-leucine endocytic retrieval signal to the extracellular surface and partially destabilized insertion of the eighth transmembrane helix. Our findings illuminate the mechanisms underlying ATP7A-related DMN and establish a link between p97/VCP and genetically distinct forms of motor neuron degeneration.

INTRODUCTION

ATP7A is a copper-transporting ATPase that helps regulate and control cellular copper homeostasis (1). Defects in ATP7A lead to Menkes disease, or its allelic variants occipital horn syndrome (OHS), and isolated distal motor neuropathy (DMN), a recently identified condition (2). Whereas Menkes disease and OHS share specific clinical and biochemical abnormalities (3), subjects with ATP7A-related DMN manifest normal serum copper, normal copper enzyme activities, normal renal tubular function and no central nervous system or connective tissue abnormalities (2). Conversely, subjects with Menkes disease and OHS are not known to develop motor neuron dysfunction (although formal neurophysiological studies have not yet been reported). These cumulative findings imply that the mechanism(s) of disease in the new allelic variant affecting purely motor neurons could be distinctly different than for Menkes and OHS (1,2). Moreover, discovery of this new allelic variant disclosed that ATP7A, and copper metabolism in general, plays a crucial role in motor neurons which remain to be fully illuminated.

ATP7A is expressed ubiquitously, resides in the trans-Golgi network (TGN) compartment of cells and transports cytoplasmic copper to that compartment for incorporation into copper enzymes. ATP7A relocates to the plasma membrane (PM) of cells in response to increased intracellular concentration of this metal (4), where it mediates copper exodus from the cell, and recycles back to the TGN, possibly via clathrin-mediated endocytosis (5). Many of the specific molecular domains responsible for the intracellular trafficking of ATP7A, and their effects, have been identified (1).

Some axonal neuropathies that are clinically similar to ATP7A-related DMN, such as Charcot–Marie–Tooth, type 2 disease, are caused by mutations in genes associated with mitochondrial function, axonal transport or endosomal trafficking (6). Other syndromes featuring motor neuron degeneration have been associated with mutations in valosin-containing protein (p97/VCP), a hexameric ATPase involved in multiple cellular functions, including vesicular trafficking and degradation of proteins by the ubiquitin (Ub)-proteasome system (UPS) (7,8).

Copper deficiency myelopathy is a well-known clinical entity, reflecting the relationship between acquired copper deficiency from various causes and mixed sensory and motor peripheral neuropathy (9–15). Patients with Menkes disease have impaired absorption of copper which leads to systemic copper deficiency from loss-of-function ATP7A mutations, whereas ATP7A mutations that cause isolated DMN have not been associated with low copper levels in blood (2).

In this study, we applied clinical, biochemical, cellular and molecular approaches to evaluate mechanisms underlying ATP7A-related DMN and begin to elucidate the normal function of ATP7A in motor neurons.

RESULTS

Patient evaluations

Three patients with classic Menkes disease (age range 17–23 months) and three patients with OHS (ages 33 months, 19 years and 31 years) underwent clinical and electrophysiological evaluation for evidence of peripheral neuropathy. There was no suggestion on physical examinations or in nerve conduction studies of DMN in any of these individuals (Supplementary Material, Table S1). These results in subjects with diverse missense or splice junction ATP7A mutations contrasted with the distinctly abnormal peripheral nervous system findings in previously studied subjects from the two families with ATP7A-related DMN (2). Clinical examinations of the latter patients, whose initial neuropathic symptoms occurred between age 2 and 61 years, were notable for distal muscle weakness and decreased deep tendon reflexes. Nerve conduction studies often showed decreased distal motor action potential amplitudes, indicative of axonal dysfunction. In the family in which the P1386S mutation segregated, affected subjects frequently showed clinical and electrophysiological evidence of both sensory and motor neuron dysfunction (2).

Altered intracellular localization of mutant ATP7A alleles causing motor neuropathy

Previous characterization of the T994I and P1386S mutant ATP7A alleles indicated delayed trafficking from the TGN in response to elevated copper concentrations in fibroblasts cultured at subnormal (30°C) temperature (2). The abnormal trafficking at 30°C raised the possibility that these variants might represent a new class of ATP7A temperature-sensitive mutations. However, yeast complementation assays to assess residual copper transport by the P1386S allele at low temperatures showed no abnormal effects (2). Thus, the precise nature of the perturbation in copper transport and its relationship to motor neuron disease remained to be elucidated.

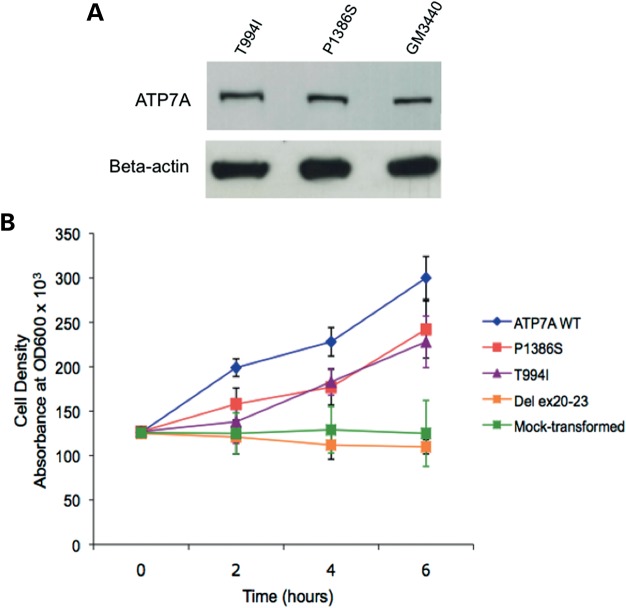

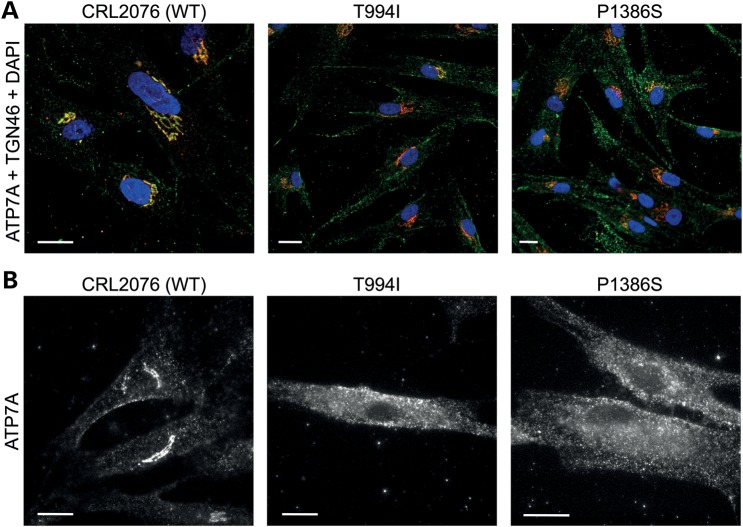

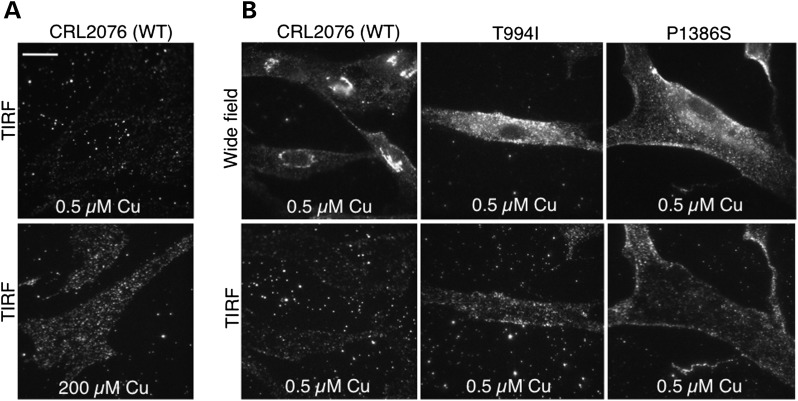

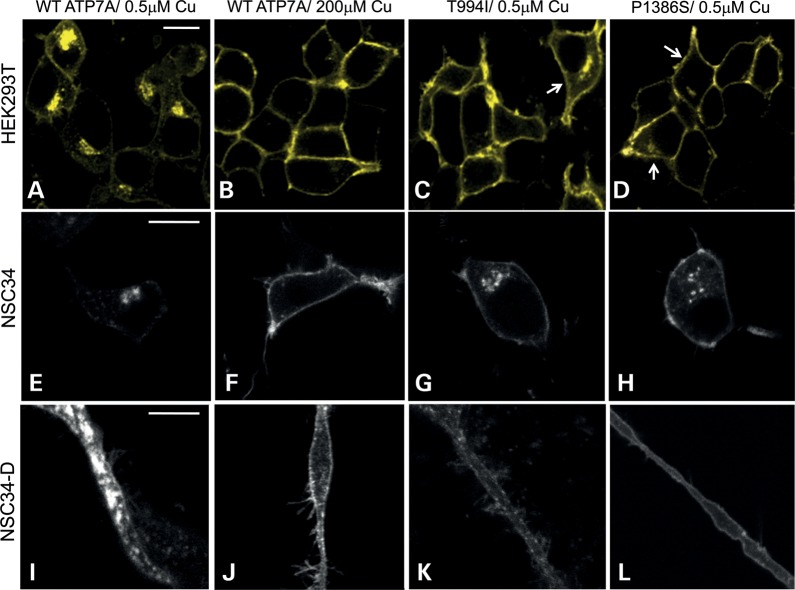

Western blot analyses confirmed normal size and quantity of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S proteins (Fig. 1A), and copper transport capacity was only slightly diminished (∼73–80% of the normal) in S. cerevisiae complementation assays (Fig. 1B). However, we found consistent evidence of diffuse ATP7A signal not localized to the TGN in ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S fibroblasts cultured at normal temperature (37°C) (Fig. 2), and sought to determine the precise location(s). Employing confocal microscopy and immunohistochemical analyses with organelle-specific markers, we found that the mutant ATP7As did not clearly co-localize in the endoplasmic reticulum, early or late endosomes, lysosomes or endocytic vesicles (Fig. 3, Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). However, total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy indicated a shift in the steady-state equilibrium of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S with increased localization in the vicinity of the PM (Fig. 4). Transfection of Hek293T and undifferentiated NSC-34 motor neuron cells with enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) Venus-tagged mutant alleles suggested a shift in the steady-state equilibrium of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S to excess PM localization relative to normal, under basal copper concentrations (0.5 µm Cu) (Fig. 5C, D, G, H). Approximately 20–30% of cells transfected with the mutant alleles showed TGN localization, in comparison to 85–90% of cells transfected with wild-type ATP7A. This pattern was reminiscent of the wild-type ATP7A signal under elevated copper exposure (200 µm Cu) (Fig. 5B and F). In differentiated NSC-34 cells (Fig. 5, NSC34-D, lower panel), neuritic projections, which stained positive for the axonal marker Tau-1 (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2), demonstrated wild-type ATP7A signal along their full length (Fig. 5I), with localization to the axonal membrane following addition of 200 µm copper to the culture medium (Fig. 5J). In contrast, the projections from differentiated NSC-34 cells transfected with ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S showed signal predominantly at the axonal membrane under basal copper concentrations (0.5 µm Cu) (Fig. 5K and L).

Figure 1.

Analyses of protein levels and copper transport function of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S. (A) Western blot of fibroblast proteins indicates normal size and quantity of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S in patients with ATP7A-related DMN. A fibroblast protein sample from a well-characterized normal cell line (GM3440) was included in the western blot as a control. Beta-actin is illustrated as a control for sample loading. (B) Yeast complementation assay, in which the S. cerevisiae copper transport knockout strain ccc2Δ was transformed with various ATP7A alleles, showed complementation ∼80% of wild-type for ATP7AP1386S and ∼73% of wild-type for ATP7AT994I. As expected, an ATP7A deletion allele (del ex20–23) did not complement the ccc2Δ copper transport knockout strain.

Figure 2.

Fibroblasts derived from individuals with ATP7A-related DMN show abnormal localization of ATP7A. (A) Color-merged images of normal human fibroblasts (CRL2076), and from patients with ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S. Cells were co-stained with antibodies against ATP7A (green) and TGN64, a trans-Golgi marker (red), and with DAPI (4′,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride) nuclear counterstain (blue). The normal cells show co-localization (yellow) of ATP7A and TGN46, whereas the mutant fibroblasts show reduced trans-Golgi localization and more diffuse ATP7A signal (green) throughout the cells. (B) Epifluorescence images of human fibroblasts stained with a carboxyl-terminal antibody to ATP7A. Note tight perinuclear signal in the wild-type cells compared with those in the affected patients' cells, in which perinuclear staining is less discrete. Scale bars = 10 µm.

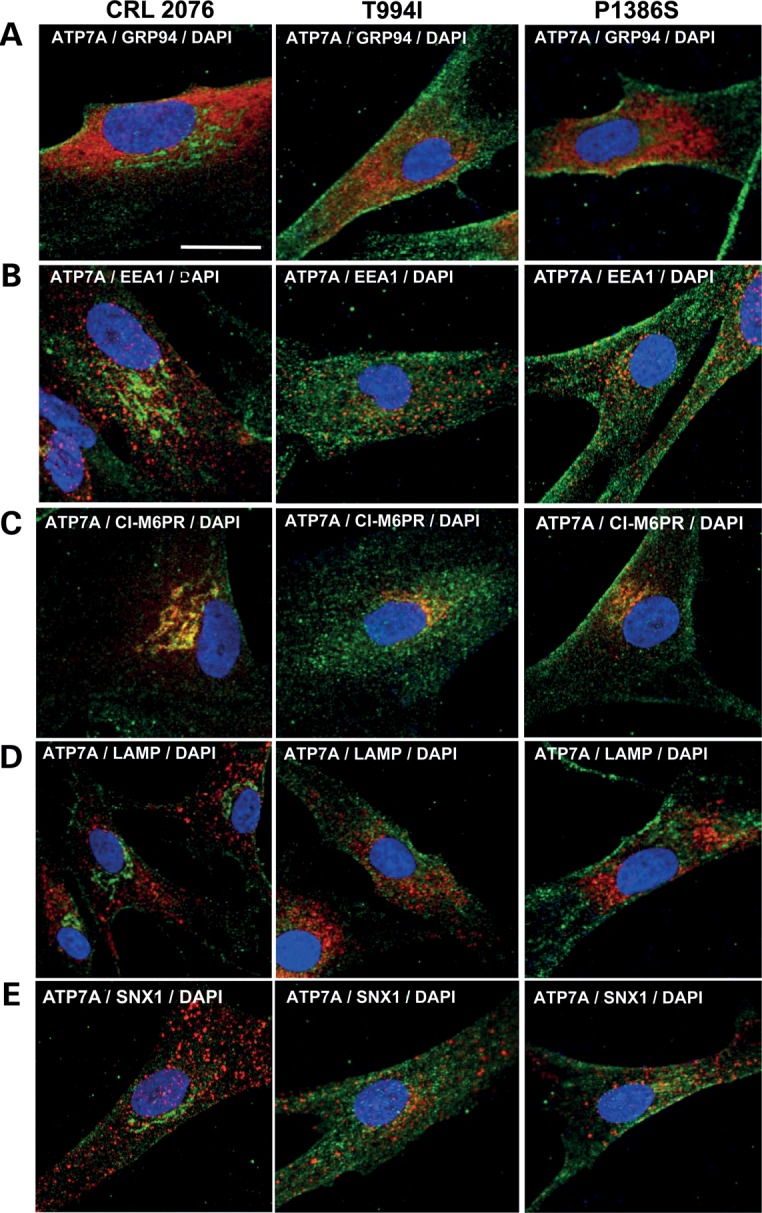

Figure 3.

Localization of wild-type and mutant ATP7As in cultured fibroblasts. Merged images of organelle-specific markers with an anti-ATP7A antibody show no obvious differences in co-localization between the mutant and wild-type ATP7As. (A) GRP94 (endoplasmic reticulum), (B) EEA1 (early endosomes), (C) cation-independent M6PR (late endosomes and Golgi), (D) LAMP1 (lysosomes) and (E) sorting nexin-1 (SNX-1; endocytic vesicles). Scale bar = 10 µm. The individually stained panels corresponding to these merged images are presented in Supplementary Material, Fig. S1.

Figure 4.

TIRF microscopy indicates a shift in the steady-state equilibrium of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S, producing increased PM localization. (A) Under normal copper concentrations (top panel), wild-type fibroblasts display minimal quantities of ATP7A signal at the PM, whereas increasing the copper concentration in the media to 200 µm for 3h (bottom panel) triggers increased accumulation, as expected. (B) Wide field epifluorescence (top panels) and TIRF (bottom panels) microscopic images of wild-type and mutant fibroblasts under basal copper conditions. Note more diffuse signal in the mutant cell wide field views and increased signal in the mutant cell TIRF images, the latter indicating excess localization at or in the vicinity of the PM relative to wild-type cells. Scale bar = 10 µm.

Figure 5.

Transfection of Hek293T cells, undifferentiated and differentiated NSC-34 motor neurons with ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S reveals a shift in the normal protein localization pattern. (A) In Hek293T cells (top panel) transfected with Venus-tagged plasmids harboring the respective ATP7A alleles, the mutant proteins demonstrate excessive PM localization under basal copper concentrations (C and D), a pattern reminiscent of the wild-type protein under increased copper exposure (B). A minority of cells transfected with mutant alleles show perinuclear (TGN) signal (arrows). In NSC-34 cells, the cell bodies and axons (induced under culture conditions that promote motor neuron differentiation) display excess PM localization when transfected with the mutant alleles (G, H, K, L). The axonal location of the Venus-tagged wild-type ATP7A in these cells is dependent on the media concentration of copper, being detected in the lumen of the axon under basal copper conditions (I), and at the axonal membrane in response to higher copper (J). Scale bar, 10 µm.

Delayed endocytic retrieval of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S

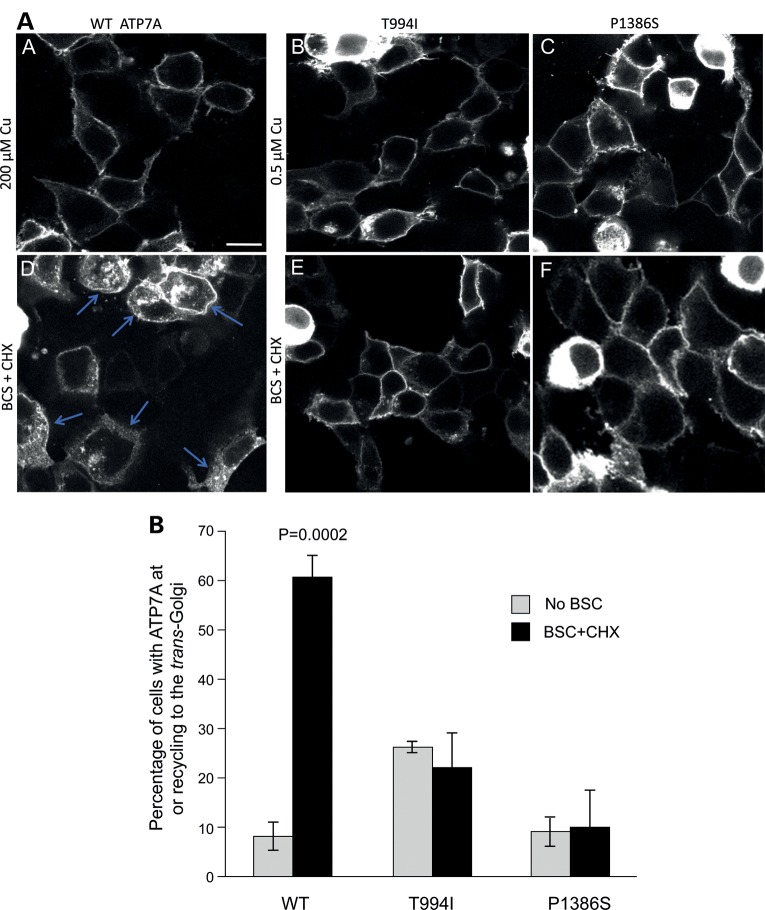

To explore the basis for increased PM localization, we evaluated endocytic retrieval of ATP7A to the TGN in transfected Hek293T cells (Fig. 6). As previously described, ATP7A ordinarily resides in the TGN and moves to the PM in response to high intracellular copper concentrations (4). Lowering intracellular copper with the copper chelator bathocuproine disulfonate (BCS) induces recycling of ATP7A from the PM back to the TGN. Thus, in order to provide an appropriate wild-type control for assessment of endocytic retrieval, we cultured Hek293T cells in high copper (200 µm) for 3 h. This treatment located wild-type ATP7A predominantly at the PM (Fig. 6A), a distribution approximating that of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S under basal copper concentrations (0.5 µm, Fig. 6Ab and c). We then concurrently treated all the transfected Hek293T cells with BCS, which, as expected, resulted in retrieval of Venus-tagged wild-type ATP7A from the PM toward the TGN (Fig. 6Ad). This fluorescent signal represented only ATP7A originally at the PM, since we co-treated all cells with cycloheximide (CHX) to eliminate de novo protein synthesis. In contrast, ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S remained largely at the PM after BCS/CHX treatment (Fig. 6Ae, f and B), indicating blocked retrograde trafficking of these mutant alleles in response to copper washout. The excess PM localization of the ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S mutant alleles was not due to aberrant interaction with lipid rafts, since sucrose gradient experiments documented co-migration with transferrin receptor, a non-raft membrane protein (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3).

Figure 6.

Impaired endocytic retrieval of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S in transfected Hek293T cells. (A) In Hek293T cells transfected with the respective Venus-tagged ATP7A alleles, cell culture media copper concentrations were used to equilibrate ATP7A location. In cells transfected with the wild-type allele, ATP7A moved from the TGN to the PM in 200 µm Cu (A), whereas in cells transfected with the mutant alleles, the ATP7A signal was already located predominantly at the PM under basal (0.5 µm Cu) copper conditions (b and c). To assess the efficiency of endocytic retrieval of ATP7A to the TGN, all Hek293T cells were treated with CHX (to halt de novo synthesis of Venus-tagged wild-type or mutant ATP7A), in combination with the copper (Cu1+) chelator, BCS to activate the expected response to low intracellular copper, namely, return from the PM to the TGN. Evidence of the expected response is detected for wild-type ATP7A (d). Note multiple Hek293T cells with abundant cytosolic fluorescent signal (arrows), representing Venus-tagged ATP7A relocating from the PM to the TGN. In contrast, there is little to no cytosolic fluorescence evident in cells harboring the ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S proteins (e and f) and the majority of Venus fluorescent signal remains at the PM. Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Bar graph summarizing intracellular localization under the conditions described. Error bars ± 1 SD.

Abnormal interaction of ATP7AT994I with p97/VCP

Since abnormal protein–protein interactions have been implicated in numerous other inherited motor neuropathies (16–20), we performed immunoprecipitation assays using total cell lysates from Hek293T cells transfected with the wild-type and two mutant ATP7A alleles (Fig. 7). The single peptide band that uniquely co-precipitated with the T994I mutant allele (Fig. 7A) was excised from a Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel, sequenced for amino acid content and identified as a 100% match to valosin-containing protein 97 (p97/VCP). The interaction between p97/VCP and ATP7AT994I was confirmed by repeat immunoprecipitation and western blotting (Fig. 7B). In the converse experiment, we documented that ATP7AT994I was selectively immunoprecipitated by p97/VCP (Fig. 7C). A distinct though less intense interaction with p97/VCP was evident for both wild-type ATP7A and ATP7AP1386S (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

Immunoprecipitation assays identify p97/VCP as an interacting protein with ATP7AT994I. (A) Coomassie brilliant blue-stained gel of proteins immunoprecipitated by a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody following transfection of Hek293T cells with the respective Venus-tagged ATP7A alleles. The larger arrow (top) indicates the Venus + ATP7A fusion protein of approximate molecular mass 206 kDa. The smaller arrow highlights a thin band, unique to ATP7AT994I, which was identified on amino acid sequencing as valosin-containing protein (p97/VCP). (B) Western blot analyses of subsequent immunoprecipitation assays to confirm the interaction of p97/VCP with ATP7A. Following transfection of Hek293T cells with the respective Venus-tagged ATP7A cDNAs, total cell protein was immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody, denatured and separated by electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with monoclonal antibodies against GFP (top two panels) or p97/VCP (bottom two panels). Small quantities of p97/VCP are detected in association with wild-type ATP7A and ATP7AP1386S, and a more prominent (10-fold higher by densitometric quantification) signal is evident in association with ATP7AT994I (third panel). The total lysate (TL) blot confirmed equivalent sample loading. (C) Following co-transfection of Hek293T cells with FLAG-tagged p97/VCP and the respective Venus-tagged ATP7A cDNAs, total cell protein was immuno-precipitated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel, denatured and separated by electrophoresis, transferred to PVDF membrane and probed with monoclonal anti-FLAG (top panel) or anti-GFP antibodies (two bottom panels). Easily visible signal is seen only in association with ATP7AT994I (middle panel). The ATP7A-Venus signal detected in the total lysates (TL) implies equivalent expression of the wild-type ATP7A, ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S alleles.

Valosin-containing protein is among >1000 proteins in the Golgi proteome (21) and also localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and nucleus (22). p97/VCP functions include vesicular trafficking (fusion of transport vesicles with target membranes), involvement in the UPS, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) and autophagy (22,23). Mutations in p97/VCP cause two autosomal dominant motor neuron diseases: inclusion body myopathy with early-onset Paget disease and frontotemporal dementia (IBMPFD), and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (7,8,22,23). The coincident occurrence of motor neuron dysfunction and myopathy in IBMPFD has been carefully discussed (8).

The interaction between ATP7AT994I and p97/VCP was not due to proteosomal degradation or ERAD, since western blots did not show excess staining with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (data not shown). Furthermore, ATP7AT994I fibroblasts and transfected Hek293T cells did not manifest increased expression of BiP or the XBP-1 splice variant, hallmarks of the mammalian misfolded protein response (24) (data not shown).

Since p97/VCP is known to interact with ubiquitin-binding (UBX) regions (25), we searched for potential sequences within ATP7A that might mimic these domains, and identified two regions of minor homology, one in a lumenal loop of ATP7A adjacent to the T994I mutation in the sixth transmembrane segment, and one in the cytoplasmic portion near the conserved phosphatase motif of ATP7A (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). Both regions feature a phenylalanine–proline (FP) dipeptide, a motif found in UBX domains and recently proposed to interact with the N domain of p97/VCP, based on the crystal structural analysis (26). The cytosolic region of homology overlaps the ATP7A actuator (A) domain, which harbors a phosphatase motif important for ATP7A dephosphorylation during the E2 stage of the Post-Albers catalytic cycle (27). Binding of p97/VCP at this site could explain PM accumulation of ATP7AT994I since mutations within or near the ATP7A phosphatase motif are known to cause sustained phosphorylation; catalytic hyperphosphorylation is associated with increased ATP7A targeting to and prolonged retention at the PM (28,29).

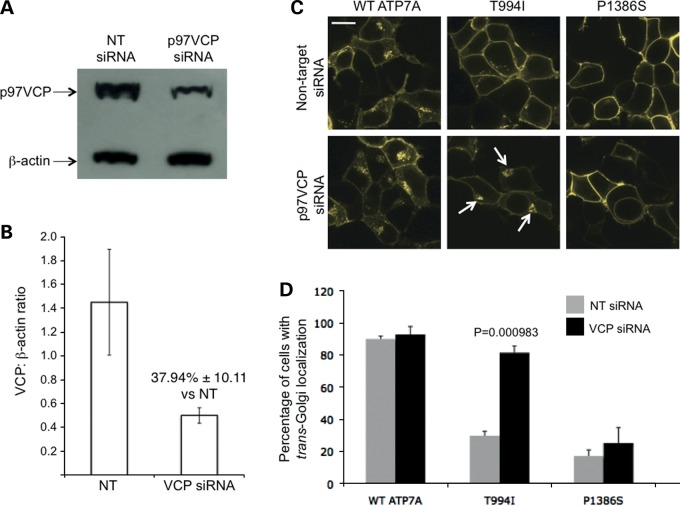

To evaluate the possible role of aberrant allosteric p97/VCP interaction in ATP7AT994I intracellular mislocalization, we performed small-interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of p97/VCP in transfected Hek293T cells. We hypothesized that knockdown would reduce interaction with p97/VCP and correct ATP7AT994I mislocalization. As predicted, cells in which p97/VCP was decreased to ∼40% of the wild-type (Fig. 8A and B) showed a significant increase in trans-Golgi localization (Fig. 8C and D).

Figure 8.

Knock-down of p97/VCP by siRNA corrects mislocalization of ATP7AT994I. (A) Western blot showing the effect of siRNA knockdown on p97/VCP protein levels in Hek293T cells transfected with wild-type ATP7A. (B) Densitometric quantification of p97/VCP knockdown by siRNA indicated reduction to ∼40% of expected in comparison to cells treated with non-target (NT) siRNA oligonucleotides. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. (C) In Hek293T cells transfected with the respective Venus-tagged ATP7A cDNAs under basal copper conditions, non-target siRNA treatment did not alter the previously determined patterns of ATP7A intracellular localization (top panels, and compare to Figure 5A, C, D), whereas siRNA against p97/VCP led to increased localization in the TGN (arrows) of cells transfected with ATP7AT994I. Scale bar = 10 µm. (D) Quantification of siRNA knockdown experiments, based on analysis of ∼500 cells in each group. Error bars ± 1 SD.

Destabilized eighth transmembrane helix insertion of ATP7AP1386S

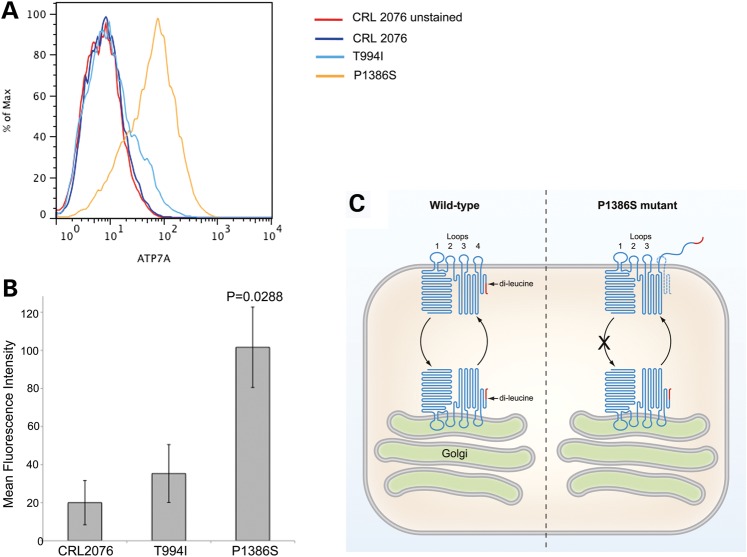

Since the interaction of p97/VCP with ATP7AP1386S was no different from the wild-type (Fig. 7B and C) and siRNA knockdown of p97/VCP did not significantly correct the P1386S cell biological phenotype (Fig. 8C and D), we considered alternative mechanisms for excess PM localization of ATP7AP1386S. The recently identified crystal structure of CopA, a bacterial homolog of ATP7A, indicated that proline 1386 is positioned precisely at the entry to the membrane (30) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4), rather than in the center of the fourth lumenal loop, as previously thought, based on hydropathy plot predictions (31). We designed fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) experiments to evaluate whether substitution of serine for proline 1386 might have a ‘helix-breaker’ effect and destabilize insertion of the eighth transmembrane domain of the molecule into the PM, as has been reported for numerous other large transmembrane proteins (32,33). This phenomenon could partly explain preferential accumulation of ATP7AP1386S at the PM, since it would result in relocation of the di-leucine signal known to mediate ATP7A endocytic retrieval (34,35) from the cytosolic to non-cytosolic protein face. Flow cytometry experiments indicated that mean fluorescence intensity from non-permeabilized fibroblasts stained with a carboxyl-terminal antibody (which includes the di-leucine signal) was significantly higher in ATP7AP1386S patient fibroblasts (Fig. 9A and B). This result suggested repositioning of the di-leucine motif and possibly the entire eighth transmembrane segment, to the extracellular surface of the PM in some fraction of the mutant molecules (Fig. 9C). This effect would likely completely abrogate copper release, since a methionine and a serine residue within this membrane segment normally coordinate copper binding (36). Thus, destabilized eighth transmembrane helix insertion is unlikely to represent the sole basis for retention of ATP7AP1386S at the PM. Our yeast complementation studies (Fig. 1B), and the affected patients' clinical and biochemical phenotypes (2), further support this interpretation.

Figure 9.

FACS suggests that the carboxyl-terminal tail of ATP7AP1386S is partially outside the PM. (A) Mean fluorescence intensity measured by flow cytometry of non-permeabilized fibroblasts exposed to a carboxyl-terminal antibody against ATP7A that includes the di-leucine endocytic retrieval signal. Fluorescent signal from this antibody was detected predominantly in ATP7AP1386S patient fibroblasts, consistent with positioning of the di-leucine motif (and possibly the entire eighth transmembrane segment) on the extracellular face of the PM. A well-characterized normal fibroblast cell line (CRL 2076) was used as control, in addition to ATP7AT994I patient fibroblasts. (B) Mean fluorescence intensity (triplicate measures) from triplicate flow cytometry experiments. Bars represent ±standard error. (C) The topological model of wild-type ATP7A in relation to the TGN and PM, illustrating partially destabilized eighth transmembrane helix insertion in ATP7AP1386S. The dashed line denotes the proper PM insertion of the eighth transmembrane segment. The epitope for the ATP7A antibody used is shown in red, and the X indicates the putative block in endocytic return of the mutant molecule to the TGN (also see Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

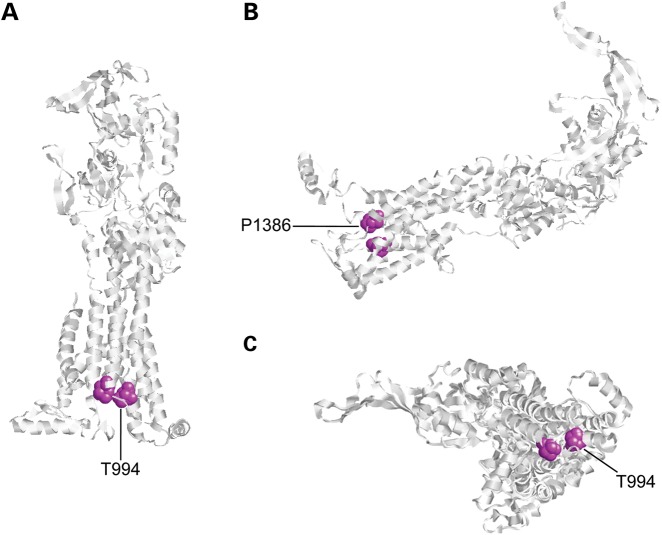

The present findings advance our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie ATP7A-related DMN. Prior characterization of the associated clinical and biochemical phenotypes of this condition suggested clear distinctions from the pathophysiology of Menkes disease and OHS (1–3). Individuals with ATP7A-related DMN manifested no central neurological problems, and had no clinical or biochemical findings similar to those observed in patients with Menkes disease or OHS. Specifically, no patients with ATP7A-related DMN examined to date have shown hair, skin or joint abnormalities, low serum copper, abnormal plasma catecholamine levels or renal tubular dysfunction, all of which are considered phenotypic hallmarks of mutations at the ATP7A locus (1). Conversely, three patients with Menkes disease and three individuals with OHS examined showed no clinical or significant electrophysiological evidence of motor neuron dysfunction (Supplementary Material, Table S1). The individuals with OHS included the first patient in whom the condition was molecularly defined (3) who is now 31 years old, and an unrelated 19 years old (37). At these ages, it would be expected for ATP7A-related DMN to be clinically manifest, if a common pathogenetic mechanism were involved. Thus, ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S do not appear to affect global copper metabolism as is evident for other ATP7A molecular defects (1,3,38). Yet these mutations, in the sixth and eighth transmembrane segments, respectively, demonstrate a specific effect on motor neuron function. Of potential relevance in this regard is the close alignment of the T994 and P1386 residues in an ATP7A model (Fig. 10) based on the crystal structure of CopA (30).

Figure 10.

Structural model of ATP7A generated by Polyview-3D and based on the crystal structure of CopA, a prokaryotic homolog (30), reveals proximity of the two amino acid residues (lavendar) associated with DMN. (A) Jmol orientation: dX = 45°, dY = 45°, dZ = 45° (B) Jmol orientation: dX = 90°, dY = 0°, dZ = 90° (C) Jmol orientation: dX = 0°, dY = 0°, dZ = 0°.

Here we show that p97/VCP interacts strongly with ATP7AT994I, linking the new ATP7A motor neuron phenotype with autosomal dominant forms of motor neuron degeneration, specifically IBMPFD and ALS (7,8,22,23). Mutations in p97/VCP have been implicated in both these latter conditions. The abnormal interaction of ATP7AT994I with p97/VCP may reduce the pool of active p97/VCP available for its normal cellular functions. Alternatively, aberrant p97/VCP-mediated vesicular trafficking or endosomal sorting of ATP7AT994I may be a crucial consequence (23). The absence of obvious protein aggregates or TDP43 pathology associated with ATP7AT994I (data not shown) implies that p97/VCP loss of function underlies this motor neuron degeneration rather than a toxic gain-of-function (39). Further investigations are needed to clarify the precise mechanism(s) through which p97/VCP perturbs motor neuron function in these unrelated disorders.

In the context of ATP7AT994I, p97/VCP may function as an allosteric inhibitor obstructing the phosphatase domain of ATP7A (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4), and extending the duration of the ATPase catalytic cycle phosphorylation (27) without entirely abrogating copper transport (Fig. 1B). The effect may delay dephosphorylation and cause retention at the PM, as previously described for hyperphosphorylated ATP7As (28,29).

A possible clue to the mechanism of impaired motor neuron function mediated by ATP7AP1386S was provided by previous case reports in which transient copper deficiency induced a mixed motor and sensory axonal neuropathy with clinical and electrophysiological findings highly similar to those in patients with ATP7AP1386S. These reports (9–15) and others document the exquisite sensitivity of motor and sensory neurons to copper deficiency of varied etiology. We hypothesize that preferential PM localization of ATP7AP1386S as shown by TIRF imaging and mammalian cell transfections produced a gradual depletion of axonal copper in vivo, since the capacity to pump copper is impaired only subtly by this mutation (Fig. 1B). Non-catalytic phosphorylation induced by the P1386S substitution, particularly in the serine-rich carboxyl-terminal region of ATP7A (40), is one consideration since increased phosphorylation of specific residues could enhance trafficking of ATP7AP1386S to the PM and mediate copper egress even under conditions of low or normal axonal copper concentrations. Formal tests using a small molecule fluorophore such as Coppersensor-3 (CS3) capable of imaging labile copper pools (41), may be useful for documenting the effect of ATP7AP1386S on axonal copper content and distribution in transfected neuronal cells or primary motor neurons. The pure motor phenotype in the T994I family (2,42) rather than the mixed motor and sensory phenotype manifested in P1386S individuals (2) suggests that axonal copper deficiency may be a causative mechanism only for the latter mutation.

The shift to excess PM localization that we delineate here for both ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S is not inconsistent with their delayed movement from the TGN in response to copper, a trafficking abnormality previously reported for these alleles (2). The slower response can be explained in one case by the presence of an abnormal ligand, p97/VCP, in association with ATP7AT994I (Fig. 7), and by trapping of the carboxyl terminal tail of some ATP7AP1386S molecules within the TGN lumen. The concept of impaired or destabilized transmembrane helix insertion is well-established for other membrane proteins, and felt to contribute to numerous disease conditions, including juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, X-linked Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, diabetes insipidus, retinitis pigmentosa, cystic fibrosis, severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy and Best macular dystrophy (32,33).

The precise fashion in which ATP7A is normally recycled from the PM to the TGN has not been established. Evidence for clathrin-dependent, clathrin-independent and caveolin-independent endocytosis has been reported (5,43). The presence of a di-leucine sorting signal in the carboxyl tail of multi-spanning transmembrane proteins (e.g. DKHSLL in ATP7A) typically denotes a capacity to bind adaptor protein/clathrin complexes, which in turn mediate rapid internalization and targeting to early endosomes (44). ATP7A mutations that alter the di-leucine signal (34,35) or which disturb dephosphorylation of the ATPase (1,28,29) may result in excess retention of ATP7A at the PM.

Our results offer further insight on the role of ATP7A in motor neuron biology. Various copper enzymes, copper transporters and copper chaperones are expressed in mouse spinal cord (45). Thus, copper clearly seems to be required for normal mammalian motor neuron function. Based on the results reported here, we postulate that ATP7A normally traffics down axons and mediates copper release from the axonal membrane of motor neurons (Fig. 5I and J). The possibility that this process is dependent on neuronal activation, calcium release or α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors as suggested for other neuronal cell populations (46–48), will require additional experimentation to document.

Finally, our findings provide a window into possible treatment approaches for symptomatic as well as pre-symptomatic individuals with ATP7AT994I or ATP7AP1386S. In the case of ATP7AT994I, motor neuron-directed viral gene therapy to add p97/VCP, or genome editing by zinc finger nucleases (49) to correct the ATP7A alteration represent potential therapeutic considerations. Copper replacement to attain serum levels near the upper limit of normal (125–150 µg/dl), or treatment with copper ionophores (50) that might enhance delivery to motor neurons could counter the axonal copper deficiency we postulate sustained PM localization of ATP7AP1386S induces. Knock-in murine models of ATP7AT994I and ATP7AP1386S will be useful for exploring the best option(s) for treatment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

All patients and patient specimens were studied under protocols approved by the NICHD or NINDS Institutional Review Board (IRB) and written informed consent was obtained from adult patients or minor patients' parents. Nerve conduction studies were performed at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD, USA, with one exception.

Cell culture

Human fibroblasts were obtained from affected patients by skin punch biopsy under sterile conditions, or from apparently healthy individual cell lines GM03440 and CRL-2076 from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ, USA) or ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA), respectively. Fibroblasts, Hek293T cells and NSC-34 neuronal cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum, antibiotics and l-glutamine under standard sterile culture conditions in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. NSC-34 cells were also cultured in differentiation medium consisting of high-glucose DMEM/Ham's F-12 (1:1) with 1% fetal calf serum and 1% non-essential amino acids for 6 days before transfections.

Cell transfections and confocal microscopy

Full-length ATP7A and human p97 VCP cDNAs were constructed by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction using total RNA as template. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate the respective ATP7A mutant alleles. After sequence fidelity was confirmed, the cDNAs were inserted between the SalI and Apa I sites of pVenus-C1. The human p97/VCP cDNA was inserted between the Bgl II and Kpn I sites of pFLAG-CMV-5.1 (Sigma). The constructs were used to transfect Hek293T cells, NSC-34 cells and differentiated NSC-34 motor neurons. Transfections were mediated by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions and were performed in triplicate. The following primary antibodies were used: sheep polyclonal TGN46 for TGN (Novus; used at 1:200); rabbit polyclonal anti-GRP94 for endoplasmic reticulum (Abcam; used at 1:200); mouse monoclonal anti-EEA1 for early endosomes (BD Biosciences; used at 1:250); mouse monoclonal anti-CI-M6PR for late endosomes (Abcam; used at 1:200); mouse monoclonal anti-LAMP1 for lysosomes (Santa Cruz; used at 1:200). Secondary antibodies used were goat anti-mouse or goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 647 (Invitrogen; used at 1:4000). Wild-type- and ATP7A-transfected cells were examined by a confocal microscope (Zeiss 510) and images captured using META software. For experiments in which ATP7A intracellular localization was quantitated, details on cell scoring are provided below.

Western blotting

Total protein was isolated from cell supernatants after lysis and centrifugation, as described above, denatured by adding 5× loading buffer with 5% β-mercaptoethanol (Quality Biological Inc.) and heating at 50°C for 10 min. Samples (40 µg total protein) were electrophoresed through 4–12% NOVEX Tris-Glycerin sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) polyacrylamide (Invitrogen), and transferred to polyvinylidine fluoride membranes. The membranes were incubated at 4°C overnight in Tris-buffered saline blocking buffer (0.9% (v/v) NaCl, 20 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5% SDS (v/v), 0.1% Tween 20 v/v) containing 5% (w/v) non-fat milk. Blots were washed with tris-buffered saline, and then incubated for 3 h with a 1:1000 dilution of rabbit anti-ATP7A antibody of known high-specificity (38), anti-β-actin (Abcam), anti-p97/VCP (BioLegend), anti-FLAG (Sigma) or anti-GFP (Clontech) antibodies. After washing, membranes were incubated with anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate (1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h at room temperature, washed and developed using SuperSignal West Pico Luminol/Enhancer Solution (Pierce), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Yeast complementation assays

The respective cDNA constructs were generated and cloned into pYES6/CT (Invitrogen) plasmids, which were used to transform the Saccharomyces cerevisiae copper transport mutant, ccc2Δ, as previously described (1,38). The transformed and mock-transformed yeast strains were cultured in copper/iron-limited solid or liquid media, as previously described (2). Growth experiments were performed in sextuplicate and the means and standard deviations calculated for the individual strains.

TIRF microscopy

Primary fibroblasts were grown in four-well chambers, in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at RT for 10 min, then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS at RT for 10 min, blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 h and probed with an anti-ATP7A rabbit antibody (1:4000) overnight. After washing twice with PBS, 10% goat serum in PBS containing Alexa fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG was applied at RT for 30 min. The buffer was then removed, the cells washed twice with PBS and images collected with an Olympus TIRF microscope at 488 objective lens (60×). Approximately 1000 cells from each cell line were examined.

Endocytic retrieval studies

Hek293T cells were transfected with WT ATP7A-EYFP (‘Venus’ enhanced yellow fluorescent protein) as described above, and pulsed with 200 μm Cu for 3 h in order to drive ATP7A to the PM and replicate the primary location of ATP7A in cells transfected with T994I and P1386S under basal copper conditions. The cell cultures were then simultaneously exposed to 50 µm BCS (to remove Cu) and 10 mm CHX (to inhibit protein synthesis) for 4 h prior to confocal imaging. For quantitation of ATP7A intracellular localization (Fig. 6B), 150–200 cells from five to eight independent confocal images per transfection were scored, and the sample means and standard deviations calculated.

Immunoprecipitation assays and amino acid sequence analyses

Hek293T cells were transfected with the respective EYFP-tagged ATP7A (Venus tag) alleles. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, the cells were rinsed thrice with PBS, and lysed in lysis buffer [50 mm Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, protein inhibitor mixture (Roche)] on ice for 20 min. The lysate was centrifuged at 10 000g for 10 min, and supernatants used for immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-GFP antibody (Clontech) and protein G agarose beads (Thermo Scientific) or anti-FLAG M2 Affinity Gel (Sigma). Immunoprecipitates were denatured with 2% SDS and electrophoresed through a 10% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Selected bands were excised and were ‘in-gel’ digested with trypsin, and the resulting peptides were extracted. Peptides were analyzed both by MALDI TOF/TOF using an ABI 4800 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) and by combined liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (LC/ESI/MS/MS) using a LCQ DECA ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fischer). Tryptic peptides were separated by reverse phase chromatography and electrosprayed directly into the sampling orifice of the mass spectrometer. MS/MS spectra were collected in a data-dependent manner, with up to three of the most intense ions in each full MS scan being subjected to isolation and fragmentation. MS/MS spectra were extracted as data files using default parameters with BioWorks v2.0 (Thermo Fisher). Peptide and protein identifications were validated using Scaffold v2.2 (Proteome Software, Portland, OR, USA). The cutoff for peptide identification was set at >95.0% probability and protein identification at >99% probability with two or more identified peptides.

siRNA assays

RNA-mediated interference of p97/VCP was performed by using siRNA duplexes purchased from Dharmacon: 5′-GCAUGUGGGUGCUGACUUA-3′, 5′-CAAAUUGGCUGGUGAGUCU-3′, 5′-CCUGAUUGCUCGAGCUGUA-3′ and 5′-GUAAUCUCUUCGAGGUAUA-3′. SiRNA oligonucleotides (100 pmoles human VCP or non-targeting siRNA) were diluted in 50 μl Opti-MEM medium and mixed gently with Lipofectamine 2000. One hundred microliter of the siRNA-Lipofectamine complex was then added to Hek293T cells in six-well plates and incubated at 37°C CO2 for 48 h. The cells were then passaged into new six-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well) or 2 × 4-well chambers (0.75 × 105 cells/well), incubated for 16 h and transfected with the respective ATP7A cDNA constructs (wild-type, T994I, P1386S). The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 24 h, and images collected with a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope. For quantitation of ATP7A intracellular localization (Fig. 8D), 550–600 cells from 17 to 19 independent confocal images per transfection were scored, and the sample means and standard deviations calculated.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Fixed, non-permeabilized fibroblasts (typically 105 cells) were incubated for 1 h at 25°C with a carboxyl-terminal ATP7A antibody in 0.1 ml of PBS containing 1% BSA. Flow cytometric data acquisition was carried out using a dual laser four-color Becton Dickinson FACSort flow cytometer. Data analysis was performed using FloJo v7.1 (Tree Star Inc., San Carlos, CA, USA) software. Triplicate experiments were performed.

Sucrose gradient experiments

Transfected Hek293T cells (2 × 107) were lysed on ice in 0.8 ml of lysis buffer [25 mmol/l Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/l NaCl, 1 mmol/l EDTA, 1 mmol/l NaF and 1 mmol/l sodium orthovanadate and the protease inhibitor mix Complete Mini (Roche)], dounce homogenized 10 times on ice and mixed with 0.8 ml of 80% sucrose made with lysis buffer. After transfer to centrifuge tubes, lysates were overlaid with 2 ml of 30% sucrose in lysis buffer, followed by 1 ml of 5% sucrose in lysis buffer. After centrifugation for 16 h at 114 562g in a Beckman SW50.1 rotor, 400 μl fractions were collected from the top of the gradient. Levels of ATP7A, transferrin receptor and flotillin 1 in each fraction were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and western blotting.

Statistical analyses

Data from siRNA and flow cytometry experiments were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t-tests. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

The work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the patients and their families for their kind collaboration. We thank the NICHD Microscopy & Imaging Core for facility use, the NICHD Biomedical Mass Spectrometry facility for peptide analysis, Peter Steinbach, Center for Molecular Modeling, Center for Information Technology, NIH for helpful discussions and the PDB file from which images in Figure 10 were generated, Tanya Lehkey, NINDS, for expert performance of nerve conduction studies and Tracey Rouault and Jerry Strauss for critical review of the manuscript. We dedicate this paper to the memory of our friend and colleague Jim Garbern, whose untimely death occurred while the manuscript was in review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaler S.G. ATP7A-related copper transport diseases-emerging concepts and future trends. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2011;7:15–29. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.180. doi:10.1038/nrneurol.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennerson M.L., Nicholson G.A., Kaler S.G., Kowalski B., Mercer J.F., Tang J., Llanos R.M., Chu S., Takata R.I., Speck-Martins C.E., et al. Missense mutations in the copper transporter gene ATP7A cause X-linked distal hereditary motor neuropathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.027. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaler S.G., Gallo L.K., Proud V.K., Percy A.K., Mark Y., Segal N.A., Goldstein D.S., Holmes C.S., Gahl W.A. Occipital horn syndrome and a mild Menkes phenotype associated with splice site mutations at the MNK locus. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:195–202. doi: 10.1038/ng1094-195. doi:10.1038/ng1094-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petris M.J., Mercer J.F., Culvenor J.G., Lockhart P., Gleeson P.A., Camakaris J. Ligand-regulated transport of the Menkes copper P-type ATPase efflux pump from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane: a novel mechanism of regulated trafficking. EMBO J. 1996;15:6084–6095. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lane C., Petris M.J., Benmerah A., Greenough M., Camakaris J. Studies on endocytic mechanisms of the Menkes copper-translocating P-type ATPase (ATP7A; MNK). Endocytosis of the Menkes protein. Biometals. 2004;17:87–98. doi: 10.1023/a:1024413631537. doi:10.1023/A:1024413631537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Züchner S., Vance J.M. Mechanisms of disease: a molecular genetic update on hereditary axonal neuropathies. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2006;2:45–53. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0071. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watts G.D., Wymer J., Kovach M.J., Mehta S.G., Mumm S., Darvish D., Pestronk A., Whyte M.P., Kimonis V.E. Inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia is caused by mutant valosin-containing protein. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:377–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1332. doi:10.1038/ng1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J.O., Mandrioli J., Benatar M., Abramzon Y., Van Deerlin V.M., Trojanowski J.Q., Gibbs J.R., Brunetti M., Gronka S., Wuu J., et al. Exome sequencing reveals VCP mutations as a cause of familial ALS. Neuron. 2010;68:857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.036. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodman B.P., Bosch E.P., Ross M.A., Hoffman-Snyder C., Dodick D.D., Smith B.E. Clinical and electrodiagnostic findings in copper deficiency myeloneuropathy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2009;80:524–527. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.144683. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2008.144683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kelkar P., Chang S., Muley S.A. Response to oral supplementation in copper deficiency myeloneuropathy. J. Clin. Neuromuscul. Dis. 2008;10:1–3. doi: 10.1097/CND.0b013e3181828cf7. doi:10.1097/CND.0b013e3181828cf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar N., Ahlskog J.E., Klein C.J., Port J.D. Imaging features of copper deficiency myelopathy: a study of 25 cases. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:78–83. doi: 10.1007/s00234-005-0016-5. doi:10.1007/s00234-005-0016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spain R.I., Leist T.P., De Sousa E.A. When metals compete: a case of copper-deficiency myeloneuropathy and anemia. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2009;5:106–111. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro1008. doi:10.1038/ncpneuro1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zara G., Grassivaro F., Brocadello F., Manara R., Pesenti F.F. Case of sensory ataxic ganglionopathy-myelopathy in copper deficiency. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009;277:184–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.10.017. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2008.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weihl C.C., Lopate G. Motor neuron disease associated with copper deficiency. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:789–793. doi: 10.1002/mus.20631. doi:10.1002/mus.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foubert-Samier A., Kazadi A., Rouanet M., Vital A., Lagueny A., Tison F., Meissner W. Axonal sensory motor neuropathy in copper-deficient Wilson's disease. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40:294–296. doi: 10.1002/mus.21425. doi:10.1002/mus.21425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irobi J., Van Impe K., Seeman P., Jordanova A., Dierick I., Verpoorten N., Michalik A., De Vriendt E., Jacobs A., Van Gerwen V., et al. Hot-spot residue in small heat-shock protein 22 causes distal motor neuropathy. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:597–601. doi: 10.1038/ng1328. doi:10.1038/ng1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puls I., Oh S.J., Sumner C.J., Wallace K.E., Floeter M.K., Mann E.A., Kennedy W.R., Wendelschafer-Crabb G., Vortmeyer A., Powers R., et al. Distal spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy caused by dynactin mutation. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:687–694. doi: 10.1002/ana.20468. doi:10.1002/ana.20468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Windpassinger C., Auer-Grumbach M., Irobi J., Patel H., Petek E., Horl G., Malli R., Reed J.A., Dierick I., Verpoorten N., et al. Heterozygous missense mutations in BSCL2 are associated with distal hereditary motor neuropathy and Silver syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:271–276. doi: 10.1038/ng1313. doi:10.1038/ng1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy J.R., Sumner C.J., Caviston J.P., Tokito M.K., Ranganathan S., Ligon L.A., Wallace K.E., LaMonte B.H., Harmison G.G., Puls I., et al. A motor neuron disease-associated mutation in p150Glued perturbs dynactin function and induces protein aggregation. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:733–745. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511068. doi:10.1083/jcb.200511068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maystadt I., Rezsohazy R., Barkats M., Duque S., Vannuffel P., Remacle S., Lambert B., Najimi M., Sokal E., Munnich A., et al. The nuclear factor kappa B-activator gene PLEKHG5 is mutated in a form of autosomal recessive lower motor neuron disease with childhood onset. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:67–76. doi: 10.1086/518900. doi:10.1086/518900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X., Simon E.S., Xiang Y., Kachman M., Andrews P.C., Wang Y. Quantitative proteomics analysis of cell cycle-regulated Golgi disassembly and reassembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:7197–7207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047084. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.047084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ju J.S., Weihl C.C. Inclusion body myopathy, Paget's disease of the bone and fronto-temporal dementia: a disorder of autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19:R38–R45. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq157. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ritz D., Vuk M., Kirchner P., Bug M., Schütz S., Hayer A., Bremer S., Lusk C., Baloh R.H., Lee H., et al. Endolysosomal sorting of ubiquitylated caveolin-1 is regulated by VCP and UBXD1 and impaired by VCP disease mutations. Nat. Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ncb2301. doi: 10.1038/ncb2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shang J. Quantitative measurement of events in the mammalian unfolded protein response. Methods Enzymol. 2011;491:293–308. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385928-0.00016-X. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-385928-0.00016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ye Y. Diverse functions with a common regulator: ubiquitin takes command of an AAA ATPase. J. Struct. Biol. 2006;156:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim K.H., Kang W., Suh S.W., Yang J.K. Crystal structure of FAF1 UBX domain in complex with p97/VCP N domain reveals a conformational change in the conserved FcisP touch-turn motif of UBX domain. Proteins. 2011 doi: 10.1002/prot.23073. doi:10.1002/prot.23073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Apell H.J. How do P-type ATPases transport ions? Bioelectrochemistry. 2004;63:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.09.021. doi:10.1016/j.bioelechem.2003.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petris M.J., Voskoboinik I., Cater M., Smith K., Kim B.E., Llanos R.M., Strausak D., Camakaris J., Mercer J.F. Copper-regulated trafficking of the Menkes disease copper ATPase is associated with formation of a phosphorylated catalytic intermediate. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:46736–46742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208864200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M208864200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim B.E., Petris M.J. Phenotypic diversity of Menkes disease in mottled mice is associated with defects in localisation and trafficking of the ATP7A protein. J. Med. Genet. 2007;44:641–646. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.049627. doi:10.1136/jmg.2007.049627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gourdon P., Liu X.Y., Skjørringe T., Morth J.P., Møller L.B., Pedersen B.P., Nissen P. Crystal structure of a copper-transporting PIB-type ATPase. Nature. 2011;475:59–64. doi: 10.1038/nature10191. doi: 10.1038/nature10191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vulpe C., Levinson B., Whitney S., Packman S., Gitschier J. Isolation of a candidate gene for Menkes disease and evidence that it encodes a copper-transporting ATPase. Nat. Genet. 1993;3:7–13. doi: 10.1038/ng0193-7. doi:10.1038/ng0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallagher M.J., Ding L., Maheshwari A., Macdonald R.L. The GABAA receptor alpha1 subunit epilepsy mutation A322D inhibits transmembrane helix formation and causes proteasomal degradation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:12999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700163104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700163104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milenkovic V.M., Rivera A., Horling F., Weber B.H.F. Insertion and topology of normal and mutant bestrophin-1 in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:1313–1321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607383200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M607383200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petris M.J., Camakaris J., Greenough M., LaFontaine S., Mercer J.F. A C-terminal di-leucine is required for localization of the Menkes protein in the trans-Golgi network. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1998;7:2063–2071. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.13.2063. doi:10.1093/hmg/7.13.2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francis M.J., Jones E.E., Levy E.R., Martin R.L., Ponnambalam S., Monaco A.P. Identification of a di-leucine motif within the C terminus domain of the Menkes disease protein that mediates endocytosis from the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 1999;112:1721–1732. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.11.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mandal A.K., Yang Y., Kertesz T.M., Argüello J.M. Identification of the transmembrane metal binding site in Cu+-transporting PIB-type ATPases. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:54802–54807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410854200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M410854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang J., Robertson S.P., Lem K.E., Godwin S.C., Kaler S.G. Functional copper transport explains neurologic sparing in occipital horn syndrome. Genet. Med. 2006;8:711–718. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000245578.94312.1e. doi:10.1097/01.gim.0000245578.94312.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaler S.G., Holmes C.S., Goldstein D.S., Tang J.R., Godwin S.C., Donsante A., Liew C.J., Sato S., Patronas N. Neonatal diagnosis and treatment of Menkes disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:605–614. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070613. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa070613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kakizuka A. Roles of VCP in human neurodegenerative disorders. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008;36:105–108. doi: 10.1042/BST0360105. doi:10.1042/BST0360105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veldhuis N.A., Valova V.A., Gaeth A.P., Palstra N., Hannan K.M., Michell B.J., Kelly L.E., Jennings I., Kemp B.E., Pearson R.B., et al. Phosphorylation regulates copper-responsive trafficking of the Menkes copper transporting P-type ATPase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2009;41:2403–2412. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.06.008. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dodani S.C., Domaille D.W., Nam C.I., Miller E.W., Finney L.A., Vogt S., Chang C.J. Calcium-dependent copper redistributions in neuronal cells revealed by a fluorescent copper sensor and X-ray fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:5980–5985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009932108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1009932108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takata R.I., Speck Martins C.E., Passosbueno M.R., Abe K.T., Nishimura A.L., Da Silva M.D., Monteiro A., Jr, Lima M.I., Kok F., Zatz M. A new locus for recessive distal spinal muscular atrophy at Xq13.1-q21. J. Med. Genet. 2004;41:224–229. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.013201. doi:10.1136/jmg.2003.013201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cobbold C., Coventry J., Ponnambalam S., Monaco A.P. The Menkes disease ATPase (ATP7A) is internalized via a Rac1-regulated, clathrin- and caveolae-independent pathway. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:1523–1533. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg166. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonifacino J.S., Traub L.M. Signals for sorting of transmembrane proteins to endosomes and lysosomes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003;72:395–447. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.2010. Allen Institute for Brain Science Allen Spinal Cord Atlas [online] http://mousespinal.brainmap.org/

- 46.Schlief M.L., Craig A.M., Gitlin J.D. NMDA receptor activation mediates copper homeostasis in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:239–246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-04.2005. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3699-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El Meskini R., Crabtree K.L., Cline L.B., Mains R.E., Eipper B.A., Ronnett G.V. ATP7A (Menkes protein) functions in axonal targeting and synaptogenesis. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.018. doi:10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peters C., Muñoz B., Sepúlveda F.J., Urrutia J., Quiroz M., Luza S., De Ferrari G.V., Aguayo L.G., Opazo C. Biphasic effects of copper on neurotransmission in rat hippocampal neurons. J. Neurochem. 2011;119:78–88,. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07417.x. Epub 2011 September 1. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li H., Haurigot V., Doyon Y., Li T., Wong S.Y., Bhagwat A.S., Malani N., Anguela X.M., Sharma R., Ivanciu L., et al. In vivo genome editing restores haemostasis in a mouse model of haemophilia. Nature. 2011;475:217–221. doi: 10.1038/nature10177. doi:10.1038/nature10177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adlard P.A., Cherny R.A., Finkelstein D.I., Gautier E., Robb E., Cortes M., Volitakis I., Liu X., Smith J.P., Perez K., et al. Rapid restoration of cognition in Alzheimer's transgenic mice with 8-hydroxy quinoline analogs is associated with decreased interstitial Abeta. Neuron. 2008;59:43–55. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.018. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.