Abstract

Recent advances in sequencing technology have led to a rapid accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences, which now represent the wide spectrum of animal diversity. However, one animal phylum – Ctenophora – has, to date, remained completely unsampled. Ctenophores, a small group of marine animals, are of interest due to their unusual biology, controversial phylogenetic position, and devastating impact as an invasive species. Using data from the Mnemiopsis leidyi genome sequencing project, we PCR amplified and analyzed its complete mitochondrial (mt-) genome. At just over 10kb, the mt-genome of M. leidyi is the smallest animal mtDNA ever reported and is among the most derived. It has lost at least 25 genes, including atp6 and all tRNA genes. We show that atp6 has been relocated to the nuclear genome and has acquired introns and a mitochondrial targeting presequence, while tRNA genes have been genuinely lost, along with nuclear-encoded mt-aminoacyl tRNA synthetases. The mt-genome of M. leidyi also displays extremely high rates of sequence evolution, which likely led to the degeneration of both protein and rRNA genes. In particular, encoded rRNA molecules possess little similarity with their homologues in other organisms and have highly reduced secondary structures. At the same time, nuclear encoded mt-ribosomal proteins have undergone expansions, probably to compensate for the reductions in mt-rRNA. The unusual features identified in M. leidyi mtDNA make this organism an interesting system for the study of various aspects of mitochondrial biology, particularly protein and tRNA import and mt-ribosome structures, and add to its value as an emerging model species. Furthermore, the fast-evolving M. leidyi mtDNA should be a convenient molecular marker for species- and population-level studies.

Keywords: Ctenophora, comparative genomics, cytonuclear coevolution

Introduction

Animal mitochondrial DNA is a small molecule that has been used extensively in population genetic, phylogenetic, and biogeographic studies (Avise, 2004). Although originally considered remarkably uniform, recent sampling has uncovered substantial diversity in the organization of animal mitochondrial genomes (Lavrov, 2011). In particular, each sampled phylum of non-bilaterian animals (e.g., Cnidaria, Placozoa, Porifera) and even most major lineages within them (e.g., demosponges vs. glass sponges) have revealed distinct modes and tempos of mitochondrial genome evolution (Kayal and Lavrov, 2008; Haen et al., 2007; Wang and Lavrov, 2008; Signorovitch et al., 2007). Substantial variation has been found in the gene content, rates of sequence evolution, structures of encoded rRNA and tRNA, genetic code used in mitochondrial translation, presence or absence of introns, and percentage of non-coding DNA (reviewed in Lavrov, 2011). To date, complete mitochondrial genome sequences have been generated for more than 2,000 animals, representing the wide spectrum of metazoan diversity and partial mtDNA sequences (such as cox1 barcodes) are available for thousands of other species (Ratnasingham and Hebert, 2007). Despite this remarkable collection of mtDNA sequences from a multitude of species, one glaring omission remains: no genuine mitochondrial sequence has been reported to date for the phylum Ctenophora.

Ctenophores are a small, well-defined phylum of mostly pelagic, carnivorous, marine animals with a simple body plan and uncertain phylogenetic affinity to other Metazoa (Harbison, 1985). They are characterized by biradial symmetry, an oral-aboral axis delimited by a mouth and an apical sensory organ, a locomotor system made of eight rows of laterally reinforced macrocilia or comb plates, and, in most species, a pair of retractable tentacles that contain specialized adhesive cells called colloblasts (Hernandez-Nicaise, 1991). All ctenophores have a well-developed gastrovascular system that functions in digestion, circulation, excretion, and reproduction. The rest of the body volume consists primarily of a poorly differentiated gelatinous mesogloea containing several cell types, including muscle cells and neurons (Hernandez-Nicaise, 1991). Most ctenophores are extremely fragile and difficult to culture and, as such, we know relatively little about their biology (Pang and Martindale, 2008b).

The lack of mtDNA data from the phylum Ctenophora is unfortunate for several reasons. From an evolutionary perspective, ctenophore lineage diverged from other animals very early in metazoan evolution. Fossils with ctenophore-like morphology have been reported from the early Cambrian period (~540 MYA) (Chen et al., 2007) and some intriguing morphological connections were suggested for Ctenophora and Ediacaran taxa (Dzik, 2002). Because ctenophores evolved independently from the rest of Metazoa for hundreds of millions of years, they may have retained some revealing mitochondrial features from their common ancestor with other animals or evolved some unique features not present anywhere else in the animal kingdom. As an aside, the popular idea that, as an early branching lineage, ctenophores should display mostly ancestral traits is incorrect (c.f., Crisp and Cook, 2005).

From a phylogenetic perspective, the mitochondrial data may help to elucidate the phylogenetic position of Ctenophora, which is still hotly debated, as well as improve our understanding of the relationship within this phylum. Traditionally, two distinct phylogenetic hypotheses have been considered for Ctenophora based on morphological and/or embryological data: (i) grouping them with Cnidaria (the Coelenterata hypothesis; Haeckel (1866) and Hyman (Hyman, 1940)), ii) placing them as a sister group to Bilateria (the Acrosomate hypothesis; (Lang, 1881; Ax, 1996)). By contrast, early molecular phylogenies tended to place ctenophores as the sister group to Cnidaria + Bilateria, either by themselves (the Planulozoa hypothesis; (Wainright et al., 1993; Wallberg et al., 2004)), or with calcareous sponges (Collins, 1998). Recent phylogenomic studies utilizing gene supermatrices based largely on EST data have yielded conflicting results as to the phylogenetic position of Ctenophora. Two of these studies placed ctenophores as the sister group to all metazoans, including sponges (Dunn et al., 2008; Hejnol et al., 2009). Phylogenomic analyses by a different group of researchers put ctenophores either in a clade with the Cnidaria, supporting the traditional Coelenterata hypothesis (Philippe et al., 2009) or as a sister group to a clade that included Cnidaria, Bilateria and Placozoa (Pick et al., 2010). Another set of studies utilized whole genome data from all four non-bilaterian phyla, including the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi, to examine gene superfamilies (Reitzel et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2010) and signaling pathway components (Pang et al., 2010) across the Metazoa. Based on the presence or absence of superfamily classes, superfamily subclasses, and pathway components, these authors supported a grouping of Cnidaria, Placozoa, and Bilateria (the ParaHoxozoa) to the exclusion of Porifera and Ctenophora (Ryan et al., 2010). Remarkably, the phylogeny within Ctenophora is also unresolved, mainly because of the surprising conservation of 18S rRNA sequences, the only marker used so far to study it (Podar et al., 2001). Thus, additional markers or new approaches are clearly needed for phylogenetic studies involving ctenophores.

Finally, from structural analyses, ctenophore mitochondria possess an unusual arrangement of tubular cristae (Horridge, 1964) unlike most other animals, fungi, and choanozoa that have flat cristae (Cavalier-Smith, 1993). Earlier studies placed heavy emphasis on these mitochondrial features in phylogenetic inference (e.g., Cavalier-Smith, 1993), although modern investigations have questioned the value of this character for phylogenetic inference (Frey and Mannella, 2000). There is little known about the reasons for this difference and whether there is any correlation between mtDNA evolution and mitochondrial morphology.

The ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi (the warty comb jelly or sea walnut) is an important predator in many pelagic marine ecosystems (Colin et al., 2010). Native to the Atlantic coast of North and South America, it has gained global notoriety for its invasion of several seas of the Mediterranean basin (Shiganova et al., 2001). This ctenophore also has become one of the model species in developmental and evolutionary biology (Pang and Martindale, 2008a). The M. leidyi genome sequencing project (Pang et al., 2010; Ryan et al., 2010; unpublished) has produced sequences for several candidate mitochondrial genes. We used this information to design primers and to PCR-amplify the complete mitochondrial genome from this species. In addition, we used the available nuclear genomic data to obtain deeper insights into the mitochondrial biology of M. leidyi. Here, we describe this genome and report its very unusual evolutionary trajectory.

Methods

Specimen collection and genomic DNA preparation

Adult Mnemiopsis leidyi were collected from the docks of Woods Hole, MA during the summers of 2006–2008. Animals were kept in fresh seawater under constant illumination in a large bucket in the lab. Adults were induced to spawn by placing them in the dark for 6–7 hours, as described in Pang and Martindale (2008a). Fertilized eggs were collected and washed with fresh seawater. The embryos were raised at 17°C for 24–36 hours (up to cydippid stage), upon which they were collected and concentrated in 2 ml tubes. These tubes were briefly centrifuged at 2,000g to concentrate cydippids (approximately 500–1000). After removing as much excess seawater as possible, these tubes were placed at −80°C prior to DNA extractions. Genomic DNA was isolated using DNAzol (Molecular Research Center) as previously described (Pang and Martindale, 2008a). DNAzol was added to tubes of cydippids immediately after they were removed from -80°C. Following an overnight proteinase K digestion (0.1 mg/ml), tubes were centrifuged at 10,000g to remove insoluble material. Genomic DNA was then precipitated by adding a half volume of ethanol and incubating at room temperature. Following centrifugation, the DNA pellet was washed with 70% DNAzol (30% ethanol), then 75% ethanol, then resuspended in sterile water.

mtDNA amplification and sequencing

Mitochondrial cox1, cob, and nad5 were identified among the sequences generated by the Mnemiopsis leidyi genome sequencing project (Entrez Project ID: 64405) and used to design specific primers: ml-cox1-f1, 5′-CGTCACTTTACATGCTGTTTAC -3′; ml-cox1-r1, 5′-ATACGAGGTAAACACATATCAGC-3′; ml-cob-f1, 5′-ATGGGTCAAATGTCATATTGAGC-3′; ml-cob-r1, 5′-TAAGTAAACTATTAATGACAGGAC-3′; ml-nad5-f1, 5′-TCTGCTGTTTTTCCATTTCATGC-3′; and ml-nad5-r1, 5′-TCCATAGCATAATATAGTCAAGC-3′. The complete mtDNA was amplified in two overlapping fragments using the Long and Accurate (LA) PCR kit from TAKARA with primer combinations i) cox1-f1+cob-r1 and cob-f1+cox1-r1 and ii) cob-f1+nad5-r1, nad5-f1+cob-r1. The total size of the two PCR fragments was identical for both sets of primers. The PCR fragments generated with cob and nad5 primers were used for the shotgun cloning and sequencing as described in our earlier paper (Burger et al., 2007). Briefly, PCR ampli cations were combined in equimolar concentration, sheared into pieces 1–2 kb in size and cloned using the TOPO Shotgun Subcloning Kit from Invitrogen. White colonies containing inserts were collected, grown overnight in 96-well blocks and submitted to the DNA Sequencing and Synthesis Facility of the ISU Of ce of Biotechnology for high-throughput plasmid preparation and sequencing. The STADEN program suite (Staden, 1996) and Phred (Ewing et al., 1998; Ewing and Green, 1998) were used to basecall and assemble the sequences. Problematic regions in the assembly (mostly due to mono-T runs) were further investigated by primer-walking. The complete mtDNA sequence has been deposited to GenBank (JF760210). Two PCR primers (meta-cox1-f2, 5′-TTKTTYTGRTTYTTYGGNCAYCC-3′ and meta-cox1-r2, 5′-GAKAAKACGTAGTGRAARTGNGC-3′) were designed for cox1 regions conserved between M. leidyi and other animals: and used to amplify a fragment of cox1 from Pleurobrachia pileus, a ctenophore belonging to the order Cydippida (GenBank accession JF760211).

Sequence analysis

We used flip (http://megasun.bch.umontreal.ca/ogmp/ogmpid.html) to predict ORFs in M. leidyi mtDNA and similarity searches in local databases with FASTA (Pearson, 1994) to identify them. Secondary structure predictions were performed using TMHMM for protein coding genes (Krogh et al., 2001). Covariance models for rns and rnl genes were constructed with Infernal 1.0 (Nawrocki et al., 2009) using manually curated alignments of the corresponding sequences from Escherichia coli, Monosiga brevicollis, Oscarella carmela, Geodia neptuni, Tethya actinia, Metridium senile, Aurelia aurita and Homo sapiens with the experimentally determined secondary structures from Escherichia coli (Glotz et al., 1981) used as consensus structures. The resulting rRNA secondary structure predictions were visualized using RNAViz (De Rijk et al., 2003). Transfer RNA sequences were searched with tRNAscan (Lowe and Eddy, 1997), Arwen (Laslett and Canback, 2008), and manually. The mt-genome map was visualized using CGView (Stothard and Wishart, 2005).

Mitochondrial ribosomal protein (MRP) sequences of interest were identified using reciprocal BlastP (Altschul et al., 1997) queries with known MRP sequences from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Homo sapiens obtained from the Uniprot database (Smits et al., 2007). The identities of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and ribosomal proteins were determined based upon homology to known sequences from S. cerevisiae and/or human obtained from the Uniprot database, and mitochondrial targeting presequence predictions were performed using TargetP (Emanuelsson et al., 2007). Intron/exon boundaries in nuclear-encoded atp6 were annotated using EST sequences from M. leidyi publicly available in Genbank.

Protein sequences for atp9 were obtained from GenBank files, Homo sapiens NP_001680, Nematostella vectensis XP_001634940, Trichoplax adhaerens XP_002108967, or by querying the predicted Amphimedon queenslandica proteome from the JGI database with the mitochondrial atp9 sequence from Amphimedon compressa. The consensus mitochondrial atp9 sequence for eukaryotes was obtained from the NCBI organellar genome resources website.

Phylogenetic analysis

Mitochondrial coding sequences for Cantharellus cibarius and Capsaspora owczarzaki mtDNA were downloaded from http://megasun.bch.umontreal.ca/People/lang/FMGP/proteins.html; other sequences were derived from the GenBank organellar genome database. Translated sequences of cob, cox1-cox3, and nad5 were aligned three times with ClustalW 2. (Larkin et al., 2007) using different combinations of opening/extension gap penalties: 10/0.2 (default), 12/4 and 5/1. The three alignments were compared using SOAP (Löytynoja and Milinkovitch, 2001), and only positions that were aligned identically among them were included in phylogenetic analyses.

Phylogenetic inference was performed with PhyloBayes (PB) v3.2d (Lartillot and Philippe, 2004; Lartillot et al., 2009). We used the CAT+GTR+Γ models for the analysis and ran four chains for 20,000 generation, until convergence (maxdiff = 0.13), sampling every 10th tree.

Results

The smallest animal mitochondrial genome with an extreme nucleotide composition

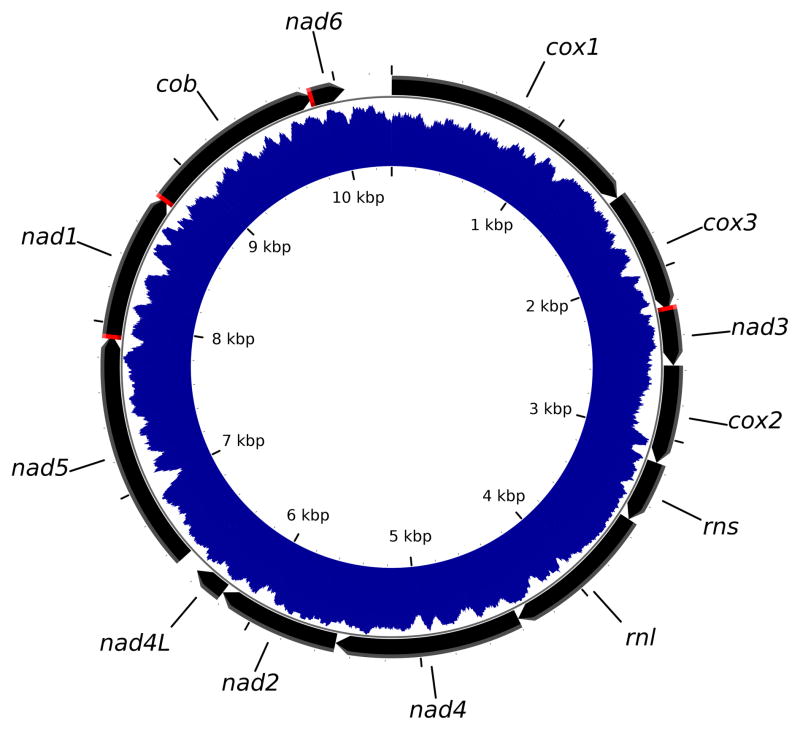

The sequence of Mnemiopsis leidyi mtDNA (Figure 1) was determined to be 10,326 bp in length, making it the smallest animal mt-genome reported to date. We attributed the extremely small size of this genome to the scarcity of intergenic nucleotides, the relocation of atp6 to the nuclear genome, and the apparent loss of all tRNA genes (see below). The sequence was also extremely AT-rich (%AT=84.3) and had a strong AT-skew of −0.38 (Perna and Kocher, 1995). As a result, we found multiple mono-T runs in the coding strand, 21 of them being greater or equal to 10 and up to 22 nucleotides in size. In some places, the mono-T runs created problems for sequencing this mitochondrial genome.

Figure 1. Mitochondrial genome map of Mnemiopsis leidyi.

Inferred protein and rRNA genes are indicated by black arrows pointing in the direction of their transcriptional orientation; regions of overlap between them are indicated in red. The blue shaded area between two internal circles indicates AT-richness of the genome, with the inner circle corresponding to 0 %AT and the other circle – to 100 %AT. The genome encodes genes for subunits 1–5 of NADH dehydrogenase (nad1–5), subunits 1–3 of cytochrome c oxidase (cox1–3), cytochrome b (cob), the large and small subunits of mt-ribosomal RNA (rnl and rns), and two genes of low-homology to other mitochondrial proteins putatively assigned as nad4L and nad6.

Highly derived coding sequences show extremely low similarity with homologues in other genomes

We located 33 open reading frames (ORFs) larger than 50 codons (the usual size of the smallest gene in animal mtDNA), by translating the mtDNA sequence using a minimally modified genetic code (with TGA=Trp), including nine ORFs ≥ 100 codons in length (Online Figure 1). The nine largest ORFs spanned most of the genome and their pattern of nucleotide usage (a larger negative AT-skew at the second position, and a higher AT content at the third) indicates that these ORFs code for functional transmembrane proteins (Chiusano et al., 2000) (Online Figure 2). Eight of them were identified by sequence similarity as genes for cytochrome b (cob), cytochrome c oxidase subunits 1–3 (cox1–3), and NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1,3,4,5 (nad1,3–5) (Figure 1). However, their sequence identity with homologous proteins in other organisms was low, ranging from 14% for nad4 to 41% for cox1 (Table 1). The last ORF – ORF241 – was putatively identified as nad2, based on the prediction of transmembrane helices in the amino-acid sequence it encodes (Krogh et al., 2001) (Online Figure 2). We also investigated six ORFs between 50 and 100 codons in length that were located in regions not covered by these genes: four ORFs downstream of the putative nad2 gene, one downstream of cob, and one downstream of cox2 (Online Figure 1). We tentatively identified two of them as nad4L, and nad6, respectively, based on the pattern of nucleotide usage ((Online Figure 2), prediction of transmembrane helices (Online Figure 3), and some sequence similarity with corresponding genes in other genomes. While none of these indicators were conclusive (the sequence similarity was low and the proteins encoded by putative the nad4L and nad6 genes were missing some transmembrane domains usually present in their homologues), we note that these genes are typically among the least conserved genes in mtDNA (Wang and Lavrov, 2008) and are therefore expected to be difficult to identify. Furthermore, the putative nad6 is unusually small in size, what contributes to its extremely low sequence identity scores. We were unable to identify genes for any subunits of F0 ATP-synthase in the mtDNA of M. leidyi, but found two of them (atp6 and atp9) in its nuclear genome (see below).

Table 1.

Coding sequences in the M. leidyi mt-genome

| Gene | Size | %AT | Start codon | Stop codon | Average similarity of encoded amino-acid sequences*

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With non-bilaterian animals1 | With bilaterian animals2 | With outgroups3 | |||||

| cob | 1086 | 79.1 | ATT(−27)4 | TAA(−14) | 27.3 | 27.4 | 26.9 |

| cox1 | 1524 | 75.7 | ATT(466) | TAA(0) | 40.4 | 41.0 | 40.5 |

| cox2 | 579 | 79.9 | ATT(0) | TAA(0) | 17.5 | 16.8 | 16.8 |

| cox3 | 726 | 84.1 | ATT(0) | TAG(−4) | 21.4 | 22.6 | 22.0 |

| nad1 | 870 | 83.7 | ATT(−1) | TAA(−27) | 21.1 | 20.3 | 20.9 |

| nad2 | 726 | 92.1 | ATT(1) | TAA(0) | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

| nad3 | 327 | 90.2 | ATA(−4) | TAA(0) | 16.6 | 15.7 | 14.4 |

| nad4 | 1095 | 88.6 | ATT(0) | TAA(1) | 14.2 | 14.1 | 14.0 |

| nad4L | 198 | 90.3 | ATG(0) | TAA(108) | 15.3 | 10.8 | 16.2 |

| nad5 | 1407 | 83.9 | ATA(108) | TAA(−1) | 14.2 | 14.5 | 14.7 |

| nad6 | 204 | 85.8 | ATG(−14) | TAA(466) | 3.7 | 2.6 | 2.9 |

Average sequence similarity with homologous proteins in Metridium senile, Sarcophyton glaucum, Ephydatia muelleri, Oscarella carmela, and Trichoplax adhaerens.

Average sequence similarity with homologous proteins in Balanoglossus carnosus, Homo sapiens, Katharina tunicata, Limulus polyphemus, and Xenoturbella blocki.

Average sequence similarity with homologous proteins in Capsaspora owczarzaki and Monosiga brevicolis.

The numbers in parentheses after initiation and termination codons show the number of noncoding nucleotides upstream and downstream of a gene. The negative numbers indicate that the genes are overlapping.

All genes in M. leidyi mtDNA had the same transcriptional polarity and several of them overlapped (specifically, cox3 and nad3, nad5 and nad1, nad1 and cob). There were very few nucleotides outside of the coding sequences, with most of them present in two regions of the genome: (i) a relatively small region downstream of the putative nad6 gene, which we interpreted as a non-coding region potentially involved in initiation of replication and transcription, and (ii) a larger region downstream of cox2, where we identified genes for the large and small subunit rRNAs.

All subunits of F0 ATP-synthase are encoded in the nuclear genome

Among the coding sequences identified in the mitochondrial genome of M. leidyi, none coded for subunits of F0 ATP-synthase. Instead, atp6 and atp9 were found in the nuclear genome. The nuclear-encoded atp6 encompassed at least 1,742 nt and contained three introns of 544, 137, and 206 bp, respectively. Corresponding cDNA sequences available in Genbank showed the mature atp6 possessing a 5′-untranslated region of nine nt, followed by an open reading frame of 756 nt and a 3′-untranslated region of 90 nt. The translated ATP6 peptide contained a 19-amino acid presequence at the N-terminus and had an 85% probability of being targeted to the mitochondrion, as predicted by TargetP (Emanuelsson et al., 2007). The amino acid sequence of the ATP6 had been predicted to form four transmembrane domains: the first encoded by exon 2, the following two by exon 3, and the last by exon 4. A fifth transmembrane domain, usually located at the N-terminus of the protein, was not identified and might have been lost.

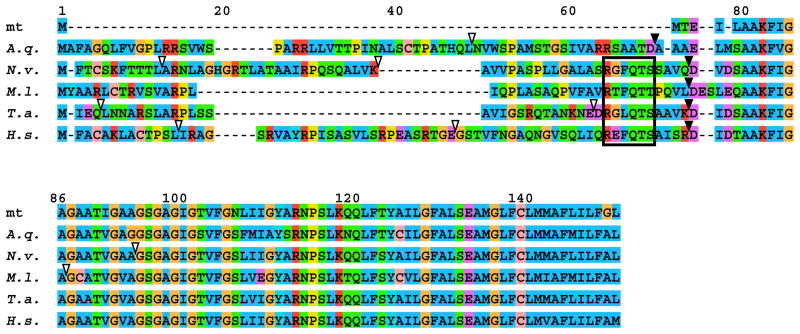

Similarly, the nuclear-encoded atp9 gene had acquired an N-terminal extension as well as one intron. Alignments of nuclear-encoded atp9 sequences from representatives of several animal phyla revealed a conserved motif just upstream of the core mitochondrial domain that was present in atp9 presequences from Ctenophora, Cnidaria, Placozoa, and Bilateria, but absent from the demosponge Amphimedon queenslandica (Figure 2), in which this gene underwent an independent transfer to the nucleus (Erpenbeck et al., 2007).

Figure 2. Comparison of atp9 sequences in M. leidyi and other animals.

Multiple sequence alignment of atp9 from Amphimedon queenslandica (A.q.), Nematostella vectensis (N.v.), Mnemiopsis leidyi (M.l.), Trichoplax adhaerens (T.a.), Homo sapiens (H.s.), and the consensus sequence from all mt-genomes available on the NCBI organellar genome resources website (mt) were created with MAFFT6 (Katoh and Toh, 2008). Presequence cleavage sites as predicted by TargetP are indicated with filled triangles, intron positions are indicated with open triangles, and the conserved motif in the presequence is marked by a rectangle.

We were not able to identify atp8 in either the mitochondrial or the nuclear genome of M. leidyi. Because of its small size and poor sequence conservation, this gene may still be present in either of these genomes or might have been lost. Multiple independent losses of atp8 have been reported in Metazoa (e.g., Hoffmann et al., 1992; Okimoto et al., 1992; Le et al., 2002; Iannelli et al., 2007; Helfenbein et al., 2004) as well as in other eukaryotes (Burger et al., 2000; Slamovits et al., 2007; Denovan-Wright et al., 1998; Hancock et al., 2010). No nuclear atp8 had been found to date in these taxa.

An extremely derived mitochondrial ribosome

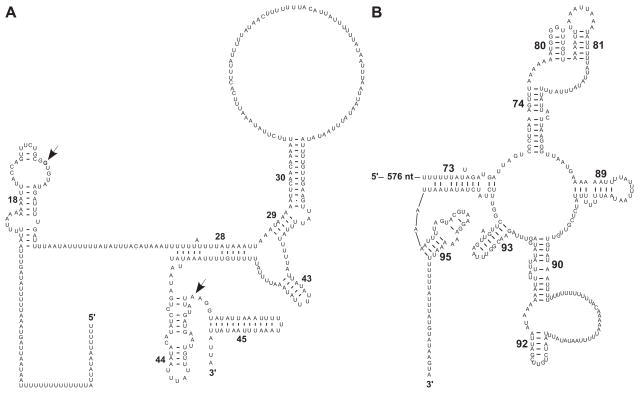

A 1246 bp region in M. leidyi mtDNA downstream of cox2 contained no large ORFs and is the presumed location of both the large and small subunit ribosomal RNA genes (rns and rnl respectively). We found a positive GC-skew in this region, consistent with a nucleotide composition influenced by rRNA secondary structures wherein G-U base pairs are frequently observed. While there was very little similarity with any known sequences, we were able to identify a few potential secondary structures that allowed us to assign the first 368 bp of the region as rns and the following 878 as rnl. Two regions within rns, the so-called 530 loop (helix 18), and helices 28–30, 43–45, were partially conserved in sequence and structure (Figure 3A). In particular, we found conservation of the three essential nucleotides (G530 in helix 18 and both A1492 and A1493 in helix 44) used in decoding, a process that discriminates against aminoacyl tRNAs that do not match the codon of messenger RNA (Ogle et al., 2003). Furthermore, a small (~110 bp) segment at the 3′ end of rnl displayed both a high degree of sequence similarity and a similar structure with the peptidyl transferase center (PTC) from domain V of the large subunit rRNA, which constitutes the “catalytic heart of the ribosome” and is highly conserved throughout all of life (Polacek and Mankin, 2005; Bokov and Steinberg, 2009) (Figure 3B). This conservation was mostly limited to the core of the PTC, while many helices involved in the A-site and P-site of the PTC had been modified or reduced. Among the retained structures were helices 80, 81 and 92, the first of which is responsible for stabilizing the P-site tRNA through base-pairing interactions with its CCA terminus (Polacek and Mankin, 2005) and the last being responsible for stabilizing the orientation of the A-site tRNA. The rest of the 1246 bp region did not encode any conserved helices in either srRNA or lrRNA. In particular, the L1-binding domain stalk, present in all other rRNAs, appears to be completely absent from rnl in M. leidyi. Clearly, the extent of reduction discovered in M. leidyi mt-rRNA is unprecedented, far surpassing that in the “minimal RNA” reported in Leishmania tarentolae mitochondrial ribosomes (de la Cruz et al., 1985a; de la Cruz et al., 1985b; Sharma et al., 2009).

Figure 3. Conserved secondary structures in M. leidyi mt-rRNAs.

Predicted secondary structures in small (A) and large subunit (B) rRNAs inferred by both manual inspection and Infernal alignments. Helices in srRNA are numbered as in in Brimacombe (1995); those in lrRNA – as in Leffers et al. (1987). Conserved nucleotide positions referenced in the text are indicated with arrows.

In mammals (Suzuki et al., 2001; Sharma et al., 2003), and other organisms (Sharma et al., 2009), the truncation of mt-rRNA is compensated by both an increase in the number and size of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPs). To investigate whether similar changes have occurred in the protein content of the M. leidyi mt-ribosome, we surveyed the nuclear genome for homologues of the 98 known MRPs that could have been present in the most recent common ancestor of opisthokonta (79 from human and 19 from yeast) (Smits et al., 2007). For comparison, we also surveyed the nuclear genome of the demosponge Amphimedon queenslandica and the cnidarian

Nematostella vectensis

We identified 34 putative homologues to human MRPs in the nuclear genome of M. leidyi compared to 61 in A. queenslandica and 62 in N. vectensis. The reduced number of identified proteins in M. leidyi is likely a result of their rapid evolution, rather than gene loss, because observed sequence identity values for these genes were generally lower between human and this ctenophore (mean=28.0, SD=6.5%) than between human and either A. queenslandica (38.2±6.5%) or N. vectensis (41.9±7.4%). In addition, the MRP sequences in M. leidyi were on average 35 amino acids longer than their homologues in human and there were more of them showing large expansions (>100 amino acids) than those showing large contractions (6 vs. 2). However, given the drastic reduction in the rRNA content of the M. leidyi mt-ribosome, it is likely that novel proteins were also recruited to compensate for the loss of rRNA.

The complete absence of mitochondrial tRNA genes and the loss of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

No tRNA genes have been found in the mitochondrial genome of M. leidyi by using either automated or manual searches. The lack of a mitochondrial gene for was especially surprising given that tryptophan appears to be specified exclusively by the UGA codon in M. leidyi mitochondrial coding sequences (no UGG codons were found), which is an “opal” stop codon in the standard genetic code. A scan of the nuclear genome of M. leidyi recovered 478 putative tRNA gene sequences and 708 possible tRNA pseudogenes, with five sequences corresponding to the nuclear trnW(cca) but no mitochondrial trnW(uca). This situation is reminiscent of that in Trypanosoma brucei, where dual targeting of tRNATrp requires two different tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetases, one of which recognizes tRNATrp that has undergone editing from C to U in the first position of the anticodon. This allows decoding of the mitochondrial UGA codons as tryptophan rather than as a stop codon (Alfonzo et al., 1999). Indeed, a search for nuclear genes for mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (mt-aaRS) recovered a putative homologue to human tryptophanyl mt-aaRS (mt-TrpRS). This was only one of two mt-aaRS found in the nuclear genome of M. leidyi, the second being mt-PheRS.

The lack of interphylum but the presence of intraphylum phylogenetic signal in mitochondrial genes

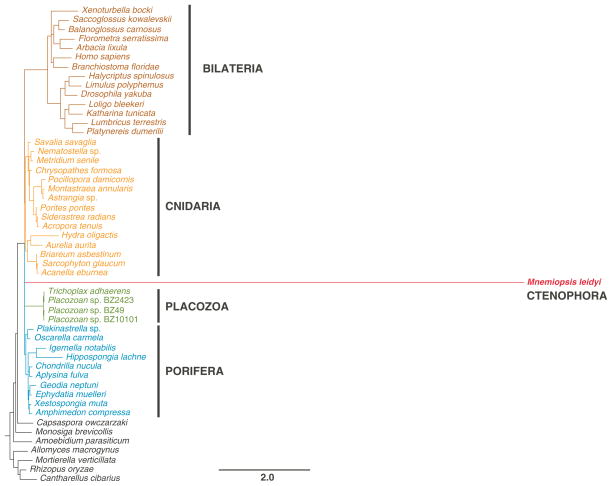

Given the exceptionally high rate of sequence evolution one can expect little if any phylogenetic signal suitable for interphylum relationships in the mitochondrial sequences of M. leidyi. Indeed, our phylogenetic analysis based on amino acid sequences from the five best-conserved genes (cob, cox1–3, and nad5) resolved neither the relationships among the four main lineages of animals sampled previously (Bilateria, Cnidaria, Porifera, and Placozoa) nor the phylogenetic position of Ctenophora (Figure 4). On the other hand, each of the main lineages was recovered as monophyletic and the relationships within each lineage corresponded closely to recently published phylogenetic studies.

Figure 4. Phylogenetic analysis of animal relationships using mitochondrial sequence data.

Posterior majority-rule consensus tree obtained from the analysis of concatenated mitochondrial amino acid sequences inferred from the five genes best-conserved in Mnemiopsis (cob, cox1–3, and nad5; 1402 aa in total). We used the CAT+F+Γ model in PhyloBayes and ran four independent chains for ~20,000 generations sampling every 10th tree after the first 1000 burnin cycles. The convergence among the chains was monitored with the maxdiff statistics and the analysis was terminated after maxdiff became less than 0.15. The number at each node represents the Bayesian posterior probability.

To check whether mtDNA sequences from ctenophores contain any intraphylum phylogenetic signal, we designed two PCR primers for cox1 regions that were well conserved between M. leidyi and other animals and used them to determine the sequence of cox1 from Pleurobrachia pileus, a ctenophore belonging to the order Cydippida. Comparison of cox1 sequences between M. leidyi and P. pileus revealed differences at 30% of sites, with dN= 0.18, dS=40.22, and dN/dS= 0.0044. The large divergence in mtDNA sequences between these two species was in stark contrast to a previous study by Podar et al. (2001) that found very little differences in nuclear 18S sequences among sampled ctenophore species. We also note that the dN/dS ratio for cox1 sequences is much less than one, indicating that cox1 in ctenophores evolves under strong purifying selection and is not a pseudogene.

Discussion

The loss of at least 25 genes explains the extreme size of the genome

Animal mtDNA, although not as highly conserved as previously thought, is an unusually small and economically organized molecule in comparison to other eukaryotic groups (Lang et al., 1999). This compact organization is particularly pronounced in the mtDNA of bilaterian animals, where intergenic nucleotides are usually few, if any, and genes contain neither introns nor regulatory sequences. The small size of animal mtDNA is also due to reduction in the sizes of genes, which, in the case of structural RNAs, often lack some secondary structures present in homologous molecules in other groups and, in other cases, are even truncated and completed by posttranscriptional polyadenylation (Yokobori and Pääbo, 1997). Given this highly economical organization of animal mtDNA, further reduction in its size is mainly possible through gene loss. Indeed, the mitochondrial genome of Mnemiopsis leidyi has lost at least 25 genes: 24 tRNA genes required for translation using the minimally derived genetic code, as well as a gene encoding subunit 6 of the F0 ATPase. The loss of a mitochondrial-encoded atp6 gene in animals has previously been reported only in Chaetognatha (Helfenbein et al., 2004). In non-metazoan eukaryotes, there are also examples of atp6 having been transferred to the nucleus, the chlorophycean alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii being the best studied (Funes et al., 2002). Interestingly, the nuclear-encoded atp6 of C. reinhardtii displays a large decrease in the hydrophobicity of the transmembrane region A, corresponding to the missing transmembrane domain in M. leidyi atp6, suggesting the absence of this domain may aid in the import of atp6 into the mitochondrion. The finding that atp6 is nuclear-encoded in M. leidyi makes it another potential model for the study of protein import to mitochondria, which is essential for mitochondrial gene therapy (Manfredi et al., 2002; Figueroa-Martinez et al., 2011).

Although atp9 was also missing in M. leidyi mtDNA, we interpreted its absence as a consequence of a nuclear transfer event that occurred in the lineage leading to all Eumetazoa (all animals minus sponges), rather than an independent transfer. Because atp9 is mitochondrial-encoded in fungi, choanoflagellates and nearly all poriferans, it was likely present in the mtDNA of the common ancestor to all animals. While parallel losses of organellar genes are common (Martin et al., 1998), the presence of a conserved motif in the presequences of the nuclear-encoded atp9 gene from Ctenophora, Cnidaria, Placozoa, and Bilateria implies these presequences share common ancestry and were therefore most likely acquired during a single ancestral nuclear transfer event (Figure 2). Although sequence convergence due to constraints imposed by the presequence cleavage mechanism could also explain the occurrence of this motif (e.g., Liu et al., 2009), we regard it as unlikely. For example, no such motif is present in the presequence of atp9 of the demosponge Amphimedon queenslandica (Erpenbeck et al., 2007), which transferred to the nucleus independently. Thus, this observation suggests that sponges, rather than ctenophores, form a sister group to the rest of the animals. It also provides further evidence that functional nuclear transfers of mitochondrial genes in addition to numt (Hazkani-Covo, 2009) have the potential to be phylogenetically informative as rare genomic changes, even when parallel transfer events are common.

In addition to atp6, the mt-genome of M. leidyi also lacks all tRNA genes. To date, the complete loss of mt-tRNA genes has been reported only in a few non-metazoans, including apixomplexa (Wilson and Williamson, 1997) and trypanosomatids (Schneider, 2001), and one species of chaetognaths (Papillon et al., 2004). Furthermore, losses of individual tRNA genes are relatively rare in the mtDNA of bilaterian animals, but are more common in demosponges, homoscleromorphs, cnidarians, and non-metazoan eukaryotes (Wang and Lavrov, 2008; Glover et al., 2001; Gray et al., 2004). In fact, all cnidarians and some demosponges lack all but one or two mt-tRNA genes.

In some cases where both nuclear and mitochondrial data are available, the loss of mt-tRNAs has been shown to be accompanied by the loss of nuclear-encoded mt-aaRS. In particular, the nuclear genome of the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis contains genes for only two mt-aaRS (mt-PheRS and mt-TrpRS) – exactly those found also in M. leidyi (Haen et al., 2010). In Nematostella, the retention of the nuclear-encoded mt-TrpRS and mt-PheRS was attributed to the reassignment of the UGA termination codon to tryptophan in animal mtDNA and the heterotetrameric structure of the cytoplasmic PheRS, respectively (Haen et al., 2010). The analogous situation in M. leidyi is consistent with these hypotheses.

Extremely derived ribosomal structures and the trend towards a minimal PTC-like ribosomal RNA

The genes that remain in the mtDNA of M. leidyi are characterized by extremely high rates of sequence evolution, which is manifested in extremely low sequence similarity between coding sequences in M. leidyi and their homologues in other animals, as well as highly unusual rRNA structures. The mt-genome of M. leidyi encodes some of the smallest and most highly derived mt-rRNA sequences ever documented. We show that the reduction in size of mt-rRNA has resulted in the elimination of many secondary structures, with the exception of those involved in decoding in the srRNA and the peptidyl transferase center in the lrRNA. This reduction has also been accompanied by an increase in the evolutionary rate and the overall size of mitochondrial ribosomal proteins.

It has been hypothesized that the ribosome may have originally evolved from a free PTC-like RNA molecule capable of catalyzing the formation of peptide bonds. Structural domains were subsequently added in modules throughout the evolution of the ribosome, mostly to stabilize the localization of tRNA molecules near the PTC and to decode messenger RNA (Bokov and Steinberg, 2009). The following accumulation of protein diversity throughout life then led to the reversal of this trend and to the their uptake within the ribosomal structure. The degenerative evolution of mitochondrial RNA genes (Lynch and Blanchard, 1998) and potentially more efficient and diverse enzymatics possible with proteins may account for the trend toward the reduction in the size of mt-rRNAs observed in animal mitochondria (Sharma et al., 2003). The rRNA genes in the mt-genome of Mnemiopsis represent the most extreme outcome of this reductionary trend ever observed in any organism.

Why M. leidyi mitochondrial genome is so derived?

The primary nonadaptive forces influencing organelle genomic evolution are mutation and random genetic drifts (Lynch et al., 2006; but see Gillespie, 2001). Mitochondrial mutation rate depends on the fidelity of mitochondrial DNA polymerase (polymerase γ in most eukaryotes (Graziewicz et al., 2006)) and the presence and efficiency of mitochondrial repair system. The power of random genetic drift, which determines the probability of fixation or removal of mutant alleles, is defined by the genetic effective size of a population (Ne) (Charlesworth, 2009). The two evolutionary forces are not independent as mutation rate influences Ne, while a small effective population size can facilitate stochastic fixation of deleterious mutations in genes responsible for DNA replication and repair that can lead to an increased mutation rate.

Two features of ctenophore reproductive biology can negatively affect their Ne and hence contribute to their accelerated mitochondrial evolution. First, ctenophores in general and M. leidyi in particular are simultaneous hermaphrodites capable of self-fertilization (Pianka, 1974; Baker and Reeve, 1974). In fact, in M. leidyi, eggs are fertilized as soon as they are shed (Pang and Martindale, 2008a). Inbreeding caused by self-fertilization is known to have effects on genome evolution as it reduced effective population size, limits the gene flow via gamete migration, and reduces the effective recombination rate between polymorphic sites (Charlesworth and Wright, 2001) Although some these effects should have less impact on mitochondrial genes, which are already uniparentally inherited in most organisms, they must influence the nuclear genes that carry out most mitochondrial functions, including replication and repair.

Second, at least some ctenophores are capable of rapid and massive reproduction. M. leidyi is an opportunistic omnivore that under optimal conditions, can start reproduction at two weeks of age and release up to 14,000 eggs per day, creating large blooms (Baker and Reeve, 1974; Purcell et al., 2001). Moreover, at least some ctenophores have the ability to reproducesexually while they are still larvae, a condition known as “dissogeny.” In M. leidyi, larvae as young as six days post-hatching and only 1.8 mm in sizewere able to produce viable embryos (Martindale, 1987). This pattern of early and rapid reproduction followed by massive die-offs could create multiple bottlenecks in the population history of M. leidyi, which facilitates the accumulation of deleterious mutations in both mitochondrial and nuclear genes.

It is also possible that the unusually high rate of sequence evolution is limited primarily to mitochondrial components in both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes and is caused by some physiological rather than population biology factors. To this end, we note that the branch leading to ctenophores is not exceptionally long in recent EST-based phylogenomic studies (Pick et al., 2010; Hejnol et al., 2009). Furthermore, a study of M. leidyi homeobox genes did not find them to be unusually derived (Ryan et al., 2010).

Conclusions

The complete mtDNA sequence of M. leidyi – the first from the phylum Ctenophora – is highly unusual in its gene content and the extent of sequence evolution. At just over 10kb, it has lost at least 25 genes, including atp6 and all tRNA genes. It also displays an exceptionally high rate of sequence evolution, resulting in highly derived structures of encoded proteins and rRNA. The availability of preliminary M. leidyi genome sequence data allowed us to investigate the associated changes in the M. leidyi nuclear genome. In particular, we show that atp6 has been transferred to the nucleus and acquired a targeting pre-sequence, and that the loss of tRNA genes from mtDNA is accompanied by the loss of nuclear encoded mt-aaRS. We also show that the rapid evolution of mt-rRNA is correlated with accelerated evolution of nuclear encoded mitochondrial ribosomal proteins. Although the extremely derived genome structure and protein-coding sequences of the M. leidyi mt-genome did not allow us to resolve the phylogenetic position of Ctenophora, our results suggest that it should be useful for phylogenetic inference within the phylum and, possibly, as a marker for biogeographic studies. In addition, this work provides a toehold for determining additional ctenophore mt-genomes, which should reveal the full range of mtDNA sequence diversity in this phylum. Finally, several unusual features identified in M. leidyi mtDNA make this organism an promising system for the study of various aspects of mitochondrial biology, particularly protein import and mt-ribosome structures, and add to its value as an emerging model species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexander Ereskovsky (Centre d’Oceanologie de Marseille) for insightful discussions, Roger P. Croll (Dalhousie University) for samples of Pleurobrachia pileus, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to the NISC Comparative Sequencing Program who made this work possible by sequencing the M. leidyi genome.

This work was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

This work was supported by the DEB-0828783 grant from National Science Foundation.

Description of Supplementary Files

The following supplementary material is available for this article:

(Online Figure 1. Figure S1. Mitochondrial genome map of Mnemiopsis leidyi showing locations of all ORFs > 50 codons. Gene names are abbreviated as in Figure 1.

(Online Figure 2. Figure S2. Nucleotide composition of coding sequences and small ORFs in M. leidyi mtDNA.

(Online Figure 3. Figure S3. Predicted transmembrane helices in Mnemiopsis leidyi (left) and Sarcophyton glaucum (right). Expected numbers of helices for each protein are shown in parentheses.

References

- Alfonzo JD, et al. C to U editing of the anticodon of imported mitochondrial tRNA(Trp) allows decoding of the UGA stop codon in Leishmania tarentolae. The EMBO journal. 1999;18:7056–7062. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.24.7056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic acids research. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avise JC. Molecular Markers, Natural History, and Evolution. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ax P. Multicellular animals: a new approach to the phylogenetic order in nature. Springer; Berlin: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baker LD, Reeve MR. Laboratory culture of the lobate ctenophore Mnemiopsis mccradyi with notes on feeding and fecundity. Marine biology. 1974;26:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Bokov K, Steinberg SV. A hierarchical model for evolution of 23S ribosomal RNA. Nature. 2009;457:977–980. doi: 10.1038/nature07749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger G, et al. Sequencing complete mitochondrial and plastid genomes. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:603–614. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger G, et al. Complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Tetrahymena pyriformis and comparison with Paramecium aurelia mitochondrial DNA. Journal of molecular biology. 2000;297:365–380. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalier-Smith T. Kingdom protozoa and its 18 phyla. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews. 1993;57:953. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.4.953-994.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B. Fundamental concepts in genetics: effective population size and patterns of molecular evolution and variation. Nature reviews Genetics. 2009;10:195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrg2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D, Wright SI. Breeding systems and genome evolution. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2001;11:685–690. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, et al. Raman spectra of a Lower Cambrian ctenophore embryo from southwestern Shaanxi, China. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6289–6292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701246104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiusano ML, et al. Second codon positions of genes and the secondary structures of proteins. Relationships and implications for the origin of the genetic code. Gene. 2000;261:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colin SP, et al. Stealth predation and the predatory success of the invasive ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17223–17227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003170107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AG. Evaluating multiple alternative hypotheses for the origin of Bilateria: an analysis of 18S rRNA molecular evidence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15458–15463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp MD, Cook LG. Do early branching lineages signify ancestral traits? Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz VF, et al. A minimal ribosomal RNA: sequence and secondary structure of the 9S kinetoplast ribosomal RNA from Leishmania tarentolae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985a;82:1401–1405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.5.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz VF, et al. Primary sequence and partial secondary structure of the 12S kinetoplast (mitochondrial) ribosomal RNA from Leishmania tarentolae: conservation of peptidyl-transferase structural elements. Nucleic acids research. 1985b;13:2337–2356. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.7.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rijk P, Wuyts J, De Wachter R. RnaViz 2: an improved representation of RNA secondary structure. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2003;19:299–300. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denovan-Wright EM, Nedelcu AM, Lee RW. Complete sequence of the mitochondrial DNA of Chlamydomonas eugametos. Plant molecular biology. 1998;36:285–295. doi: 10.1023/a:1005995718091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn CW, et al. Broad phylogenomic sampling improves resolution of the animal tree of life. Nature. 2008;452:745–749. doi: 10.1038/nature06614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzik J. Possible ctenophoran affinities of the Precambrian “sea-pen” Rangea. Journal of morphology. 2002;252:315–334. doi: 10.1002/jmor.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, et al. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erpenbeck D, et al. Mitochondrial Diversity of Early-Branching Metazoa Is Revealed by the Complete mt Genome of a Haplosclerid Demosponge. Molecular biology and evolution. 2007;24:19–22. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome research. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, et al. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome research. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Martinez F, et al. What limits the allotopic expression of nucleus-encoded mitochondrial genes? The case of the chimeric Cox3 and Atp6 genes. Mitochondrion. 2011;11:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey TG, Mannella CA. The internal structure of mitochondria. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2000;25:319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01609-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funes S, et al. The typically mitochondrial DNA-encoded ATP6 subunit of the F1F0-ATPase is encoded by a nuclear gene in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:6051–6058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109993200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JH. Is the population size of a species relevant to its evolution? Evolution; international journal of organic evolution. 2001;55:2161–2169. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2001.tb00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glotz C, et al. Secondary structure of the large subunit ribosomal RNA from Escherichia coli, Zea mays chloroplast, and human and mouse mitochondrial ribosomes. Nucl Acids Res Nucleic Acids Research. 1981;9:3287–3306. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.14.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover KE, Spencer DF, Gray MW. Identification and structural characterization of nucleus-encoded transfer RNAs imported into wheat mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:639–648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007708200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray MW, Lang BF, Burger G. Mitochondria of protists. Annual review of genetics. 2004;38:477–524. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.37.110801.142526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziewicz MA, Longley MJ, Copeland WC. DNA polymerase gamma in mitochondrial DNA replication and repair. Chemical reviews. 2006;106:383–405. doi: 10.1021/cr040463d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeckel E. Generelle Morphologie der Organismen: allgemeine Grundzüge der organischen Formen-Wissenschaft, mechanisch begründet durch die von Charles Darwin reformirte Descendenz-Theorie. G. Reimer; Berlin: 1866. [Google Scholar]

- Haen KM, et al. Glass Sponges and Bilaterian Animals Share Derived Mitochondrial Genomic Features: A Common Ancestry or Parallel Evolution? Molecular biology and evolution. 2007;24:1518–1527. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haen KM, Pett W, Lavrov DV. Parallel loss of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and mtDNA-encoded tRNAs in Cnidaria. Molecular biology and evolution. 2010;27:2216–2219. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock L, Goff L, Lane C. Red algae lose key mitochondrial genes in response to becoming parasitic. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:897–910. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbison GR. On the classification and evolution of the Ctenophora. In: Conway Morris S, George JD, Gibson R, Platt HM, editors. The origins and relationships of lower invertebrates. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1985. pp. 78–100. [Google Scholar]

- Hazkani-Covo E. Mitochondrial insertions into primate nuclear genomes suggest the use of numts as a tool for phylogeny. Molecular biology and evolution. 2009;26:2175–2179. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejnol A, et al. Assessing the root of bilaterian animals with scalable phylogenomic methods. Proceedings. Biological sciences/The Royal Society; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfenbein KG, et al. The mitochondrial genome of Paraspadella gotoi is highly reduced and reveals that chaetognaths are a sister group to protostomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10639–10643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400941101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Nicaise ML. Microscopic Anatomy of Invertebrates, Volume 2: Placozoa, Porifera, Cnidaria, and Ctenophora. AR Liss; 1991. Ctenophora; pp. 359–418. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann RJ, Boore JL, Brown WM. A novel mitochondrial genome organization for the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis. Genetics. 1992;131:397–412. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horridge GA. The giant mitochondria of ctenophore comb plates. QJ micr Sci. 1964;105:301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman LH. The Invertebrates: Protoza Through Ctenophora. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Iannelli F, et al. The mitochondrial genome of Phallusia mammillata and Phallusia fumigata (Tunicata, Ascidiacea): high genome plasticity at intra-genus level. BMC evolutionary biology [electronic resource] 2007;7:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Toh H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief Bioinform. 2008;9:286–298. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayal E, Lavrov DV. The mitochondrial genome of Hydra oligactis (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) sheds new light on animal mtDNA evolution and cnidarian phylogeny. Gene. 2008;410:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogh A, et al. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. Journal of molecular biology. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A. Der Bau von Gunda segmentata und die Verwandtschaft der Plathelminthen mit Coelenteraten und Hirudineen. 1881. [Google Scholar]

- Lang BF, Gray MW, Burger G. Mitochondrial genome evolution and the origin of eukaryotes. Annual review of genetics. 1999;33:351–397. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot N, Lepage T, Blanquart S. PhyloBayes 3: a Bayesian software package for phylogenetic reconstruction and molecular dating. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009;25:2286–2288. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lartillot N, Philippe H. A Bayesian mixture model for across-site heterogeneities in the amino-acid replacement process. Molecular biology and evolution. 2004;21:1095–1109. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett D, Canback B. ARWEN: a program to detect tRNA genes in metazoan mitochondrial nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2008;24:172–175. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavrov DV. Key transitions in animal evolution: a mitochondrial DNA perspective. In: Desalle R, Schierwater B, editors. Key transitions in animal evolution. Science Publishers; Enfield, NH: 2011. pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Le TH, Blair D, McManus DP. Mitochondrial genomes of parasitic flatworms. Trends in parasitology. 2002;18:206–213. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(02)02252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffers H, et al. Evolutionary relationships amongst archaebacteria. A comparative study of 23 S ribosomal RNAs of a sulphur-dependent extreme thermophile, an extreme halophile and a thermophilic methanogen. Journal of molecular biology. 1987;195:43–61. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90326-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SL, et al. Comparative analysis of structural diversity and sequence evolution in plant mitochondrial genes transferred to the nucleus. Molecular biology and evolution. 2009;26:875–891. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic acids research. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löytynoja A, Milinkovitch MC. SOAP, cleaning multiple alignments from unstable blocks. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2001;17:573–574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.6.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Koskella B, Schaack S. Mutation pressure and the evolution of organelle genomic architecture. Science. 2006;311:1727–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.1118884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Blanchard JL. Deleterious mutation accumulation in organelle genomes. Genetica. 1998;102–103:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi G, et al. Rescue of a deficiency in ATP synthesis by transfer of MTATP6, a mitochondrial DNA-encoded gene, to the nucleus. Nature genetics. 2002;30:394–399. doi: 10.1038/ng851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin W, et al. Gene transfer to the nucleus and the evolution of chloroplasts. Nature. 1998;393:162–165. doi: 10.1038/30234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martindale MQ. Larval reproduction in the ctenophore Mnemiopsis mccradyi (order Lobata) Marine biology. 1987;94:409–414. [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki EP, Kolbe DL, Eddy SR. Infernal 1.0: inference of RNA alignments. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009;25:1335–1337. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle JM, Carter AP, Ramakrishnan V. Insights into the decoding mechanism from recent ribosome structures* 1. Trends in biochemical sciences. 2003;28:259–266. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okimoto R, et al. The mitochondrial genomes of two nematodes, Caenorhabditis elegans and Ascaris suum. Genetics. 1992;130:471–498. doi: 10.1093/genetics/130.3.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang K, Martindale MQ. Comb jellies (ctenophora): a model for Basal metazoan evolution and development. CSH Protoc. 2008a;2008 doi: 10.1101/pdb.emo106. pdb.emo106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang K, Martindale MQ. Ctenophores. Current biology: CB. 2008b;18:R1119–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang K, et al. Genomic insights into Wnt signaling in an early diverging metazoan, the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. Evodevo. 2010;1:10. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papillon D, et al. Identification of chaetognaths as protostomes is supported by the analysis of their mitochondrial genome. Molecular biology and evolution. 2004;21:2122–2129. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson WR. Using the FASTA program to search protein and DNA sequence databases. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 1994;25:365–389. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-276-0:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perna NT, Kocher TD. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. Journal of molecular evolution. 1995;41:353–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00186547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe H, et al. Phylogenomics revives traditional views on deep animal relationships. Current biology: CB. 2009;19:706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianka ND. Ctenophora. In: Giese AC, Pearse JS, editors. Reproduction of Marine Invertebrates. Vol. 1 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Pick KS, et al. Improved phylogenomic taxon sampling noticeably affects non-bilaterian relationships. Molecular biology and evolution. 2010 doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podar M, et al. A molecular phylogenetic framework for the phylum Ctenophora using 18S rRNA genes. Molecular phylogenetics and evolution. 2001;21:218–230. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polacek N, Mankin AS. The ribosomal peptidyl transferase center: structure, function, evolution, inhibition. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2005;40:285–311. doi: 10.1080/10409230500326334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell JE, et al. The ctenophore Mnemiopsis in native and exotic habitats: US estuaries versus the Black Sea basin. Hydrobiologia. 2001;451:145–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingham S, Hebert PD. bold: The Barcode of Life Data System. Molecular ecology notes. 2007;7:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.01678.x. http://www.barcodinglife.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Reitzel AM, et al. Nuclear receptors from the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi lack a zinc-finger DNA-binding domain: lineage-specific loss or ancestral condition in the emergence of the nuclear receptor superfamily? Evodevo. 2011;2:3. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JF, et al. The homeodomain complement of the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi suggests that Ctenophora and Porifera diverged prior to the ParaHoxozoa. Evodevo. 2010;1:9. doi: 10.1186/2041-9139-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A. Unique aspects of mitochondrial biogenesis in trypanosomatids. International journal for parasitology. 2001;31:1403–1415. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MR, et al. Structure of the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome reveals an expanded functional role for its component proteins. Cell. 2003;115:97–108. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00762-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma MR, et al. Structure of a mitochondrial ribosome with minimal RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9637–9642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901631106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiganova T, et al. Population development of the invader ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi, in the Black Sea and in other seas of the Mediterranean basin. Marine biology. 2001;139:431–445. [Google Scholar]

- Signorovitch AY, Buss LW, Dellaporta SL. Comparative Genomics of Large Mitochondria in Placozoans. PLoS genetics. 2007;3:e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slamovits CH, et al. The highly reduced and fragmented mitochondrial genome of the early-branching dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina shares characteristics with both apicomplexan and dinoflagellate mitochondrial genomes. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;372:356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits P, et al. Reconstructing the evolution of the mitochondrial ribosomal proteome. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35:4686–4703. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staden R. The Staden sequence analysis package. Molecular biotechnology. 1996;5:233–241. doi: 10.1007/BF02900361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothard P, Wishart DS. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2005;21:537–539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, et al. Structural compensation for the deficit of rRNA with proteins in the mammalian mitochondrial ribosome. Systematic analysis of protein components of the large ribosomal subunit from mammalian mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:21724–21736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100432200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainright PO, et al. Monophyletic origins of the metazoa: an evolutionary link with fungi. Science. 1993;260:340–342. doi: 10.1126/science.8469985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallberg A, et al. The phylogenetic position of the comb jellies (Ctenophora) and the importance of taxonomic sampling. Cladistics: the international journal of the Willi Hennig Society. 2004;20:558–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lavrov DV. Seventeen new complete mtDNA sequences reveal extensive mitochondrial genome evolution within the Demospongiae. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson RJ, Williamson DH. Extrachromosomal DNA in the Apicomplexa. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews. 1997;61:1–16. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.1.1-16.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokobori S, Pääbo S. Polyadenylation creates the discriminator nucleotide of chicken mitochondrial tRNA(Tyr) Journal of molecular biology. 1997;265:95–99. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.