Abstract

Objective

Examined the effect of perceived child anxiety status on parental latency to intervene with anxious and non-anxious youth.

Method

Parents (68) of anxiety-disordered (PAD) and non-anxiety-disordered (56: PNAD) children participated. Participants listened and responded to an audio vignette of a parent-child interaction: half were told the child was anxious and half were given a neutral description. Participants completed measures of anxiety and emotional responding before and after the audio vignette, and signaled when the mother on the vignette should accommodate the child.

Results

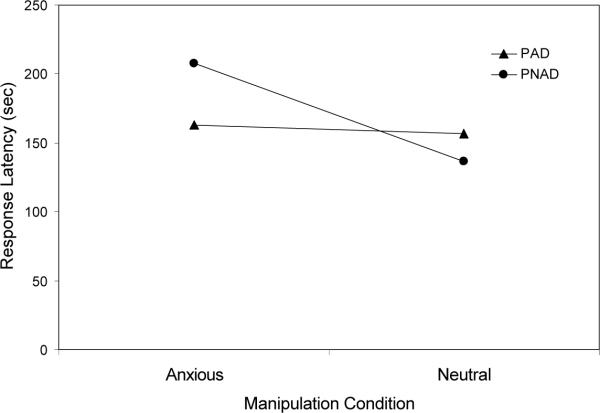

Whereas PNAD responded significantly faster when provided with neutral information about the child than when told the child was anxious, PAD did not differ in response latency. However, PAD exhibited a significant increase in state anxiety and negative affect and a decrease in positive affect after the vignette, whereas PNAD did not.

Conclusions

Results suggest that PNAD are more flexible and adaptable in their parenting behavior than PAD and that the greater anxiety and emotional lability of PAD may influence their parenting. Suggestions for research are discussed.

Keywords: Anxiety, Child Anxiety, Parenting, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Phobia, Separation Anxiety Disorder

Models of the development of youth anxiety (e.g., Rapee, 2001) highlight a role for parenting; research focuses in large part on parents' control and modeling/reinforcement of anxious behavior. With regard to control, studies suggest that excessive control may not be unique to anxiety (Hudson & Rapee, 2001, 2002) and that parental anxiety may moderate the relationship between control and child anxiety (Whaley, Pinto, & Sigman, 1999). Regarding modeling, research finds that parents encourage avoidance in anxious situations and that parents and children may shape each other in ways that reinforce the child's anxiety (e.g., Family Enhancement of Avoidant Response effect studies; Barrett, Rapee, Dadds, & Ryan, 1996; Chorpita, Albano, & Barlow, 1996; Creswell, Schniering, & Rapee, 2005). Additionally, studies indicate that the more parents express fears and model anxious behavior, the more anxious their children (Burstein & Ginsburg, 2010; Muris, Meesters, Merckelbach, & Hulsenbeck, 2000; Turner, Beidel, Roberson-Nay, & Tervo, 2003). Research also indicates that parents of youth with AD expect children to be avoidant, to have poor coping abilities, and to be less likely to succeed (Cobham, Dadds, & Spence, 1999; Kortlander, Kendall, & Panichelli-Mindel, 1997).

Although promising and somewhat consistent, the reliance on cross-sectional and correlational designs and on self-reports in many studies limits the conclusions. Additionally, research has not adequately addressed the parental behavior of intervening for the child in anxious situations. Children who use coping skills, rather than safety-seeking behavior, to face feared situations are thought to develop a sense of mastery and to be more confident to enter future anxiety-provoking situations (e.g., Hedtke, Kendall, & Tiwari, 2009). Research has shown that parents encourage anxious behavior, but it is also possible that parents intervene in anxious situations too soon, thereby thwarting mastery experiences. Furthermore, with the exception of the studies by Hudson and Rapee (2001, 2002), the current body of research has not sufficiently addressed whether the parenting behaviors are specific to parents' interactions with a certain type of child. It is possible that parents particularly respond to an anxious child in a manner consistent with their belief that the child is sensitive and in need of protection or that they might have modified the way they interact given the child's history. Parenting behavior might also be due to parental anxiety, experiential avoidance, and intolerance of negative affect. Research indicates that anxious parents may engage in behavior that increases their child's vulnerability to anxiety because they feel less perceived control over children's behavior (Wheatcroft & Creswell, 2007; Woodruff-Borden, Morrow, Bourland, & Cambron, 2002). Others theorize that experiential avoidance (EA), or unwillingness to remain in contact with certain experiences, may play a role due to parents' intolerance of their child's anxiety and to questions about their child's ability to manage anxiety (Greco, Blackledge, Coyne, & Ehreneich, 2005). Indeed, studies find that parents who avoid negative emotion also respond in ways to avoid such experiences for their children and report high levels of parenting control (Cheron, Ehrenreich, & Pincus, 2009; Tiwari et al., 2008). This suggests that intrusive parenting might result from intolerance of the child's distress and/or parents' distress, but more researching addressing this hypothesis is needed.

Given the lack of experimental research in this area, the current study used an experimental design to examine parental behavioral and emotional responses to children's anxious behavior. To investigate the concept of excessive parental intervention and rescuing behavior, we examined how parents of anxiety-disordered children (PAD) and parents of non-anxiety-disordered children (PNAD) responded to an audio vignette of a mother and child in an interaction in which the child is asked to perform an anxiety-provoking task and displays anxious/avoidant behavior. To assess the question of whether parents would respond to an anxious child in the same way they might to another child, we manipulated information about the child prior to the vignette, so parents either heard an anxious or neutral child description. Parents responded to indicate when they would intervene for the child and we measured parental anxiety and emotion pre- and post-vignette. We hypothesized that PAD would show a significantly shorter latency than PNAD to intervene regardless of the child's assigned anxiety status, with greater differences when the child in the vignette was “anxious.” We hypothesized similar findings with regard to the arousal variables, state anxiety and positive and negative affect.

METHOD

Participants

Each family included a child aged 7–14 years and at least one parent. The sample of 124 parents and 82 children were from 46 treatment-referred families and 36 volunteer families. Of the 124 parents, there were 81 mothers and 43 fathers. The parents were 75% Caucasian, 13.7% African American, 5.6% Hispanic, .8% Asian, and .8% other. Of the 82 children, there were 39 girls and 43 boys. The children were 70.7% Caucasian, 18.3% African American, 6.1% Hispanic, 1.2% Asian, and 3.7% other. Income ranged from <10,000 – >80,000 (M = 58,300).

PAD participated prior to their child receiving anxiety treatment at an urban clinic. Cases were referred from agencies, psychiatrists, schools, etc. The PAD group consisted of mothers and fathers of youth who met DSM-IV criteria for a principal diagnosis of separation anxiety disorder (SAD), social phobia (SP), or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) on composite of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV, Child and Parent Version (Silverman & Albano, 1996). The principal diagnoses of the anxious children (AD) were: 39.1% principal GAD, 17.4% principal SP, 15.2% coprincipal GAD and SP, 15.2% principal SAD, 8.7% coprincipal GAD and SAD, 2.2% coprincipal SAD and SP, and 2.2% coprincipal GAD, SAD, and SP. 23.9% of the AD also met criteria for ADHD or ODD. The parent exclusion criterion was inability to speak English. Child exclusion criteria were psychosis, mental retardation, and concurrent treatment or anti-anxiety/anti-depressant medications.

PNAD participants, recruited through media, were from the same region as PAD. The PNAD group consisted of mothers and fathers of youth (aged 7–14 years), with the exclusion criterion being inability to speak English. Exclusion criteria for the non-anxiety-disordered child (NAD) participants were the same, with one exception: children who met criteria for an anxiety disorder on the ADIS-IV-C/P were excluded (n = 2). With regard to diagnoses in the PNAD group, 88.9% had no diagnosis and 11.1% met criteria for ADHD.

Measures

Parenting

Parent-Child Interaction Vignette

Parents listened to an audio portrayal of a situation in which a child displayed anxious/avoidant behavior and distress; furthermore, they responded to the interaction by pressing a computer key at the point in which they would intervene (akin to experimental date rape analog measure used in Marx, Gross, & Adams, 1999). The vignette depicted a mother and child in public and the child asking to go to the bathroom. The mother wants the child to ask someone for help in locating the bathroom and to make the trip alone. The child displays hesitance to perform, with escalation in anxious thought, avoidance, and distress in response to the mother's requests. The vignette ends in the child crying and throwing a tantrum1. Prior to use, the vignette was pilot-tested and rated for (a) whether it was successful in suggesting that fear/anxiety were driving the child's behavior; and (b) whether it was realistic by 7 experts in child anxiety disorders and 3 postdoctoral child anxiety fellows, 10 PAD, and 10 PNAD. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale for success in suggesting anxiety, 1 = not at all, 5 = very much; and for realism, 1 = not at all realistic, 5 = extremely realistic. The mean ratings for the experts and fellows were 4.8 for success in suggesting anxiety and 4.7 for realism. The mean ratings for PAD were 4.7 for success in suggesting anxiety and 4.8 for realism. The mean ratings for PNAD were 4.6 for success in suggesting anxiety and 4.5 for realism. These ratings indicate that the vignette was suggestive of anxiety and sufficiently realistic. Parents listened to the audio vignette, with the dependent variable (DV) being a key press at the time when they thought the mother on the tape should “do what the child is asking her to do.” Participants' response latencies, recorded automatically in seconds, were the time elapsed between the start of the audio and the key press.

Child Anxiety: Diagnosis and Symptom Severity

Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children, DSM-IV edition, Child and Parent Versions (ADIS-IV-C/P; Silverman & Albano, 1996)

The ADIS-IV-C/P is a semi-structured interview for DSM-IV diagnoses in youth. During the interview, parents and children make impairment ratings: “0” for no impairment to “8” for severe impairment, interference, and/or distress. Interviewers assign Clinician Severity Ratings (CSR; 0–8; ≥ 4 required for a diagnosis). CSRs categorize a diagnosis as principal, co-principal, or secondary. Diagnoses are derived separately based on child and parent report, with a composite used to determine eligibility. The ADIS-C/P has favorable psychometric properties (March & Albano, 1998), including high interrater reliability (r = .93 for the child interview; Silverman & Nelles, 1988) and retest reliability (κ = .76 for the parent interview; Silverman & Eisen, 1992; Silverman, Saavedra, & Piña, 2001). Yearly reliability checks examined 30% of randomly selected interviews. Interrater reliability was κ =.73.

Anxiety and Emotional Response

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, 1983)

The STAI assesses how respondents generally feel (20-item A-Trait) and respondents' feelings at that moment (20-item A-State). Factor analyses support the state-trait distinction (Spielberger, 1983; Kendall, Finch, Auerbach, Hooke, & Mikulka, 1976). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (almost never), 2 (sometimes), 3 (often), to 4 (almost always). The A-Trait scale has adequate retest reliability, whereas the A-State scale reflects anxious responding to more immediate cues. Both scales possess high internal consistency and adequate convergent and divergent validity (Stanley, Beck, & Zebb, 1996). In this study, Cronbach's alpha was .90 (A-Trait) and .93 (A-State). Parents completed the A-Trait and the A-State prior to the vignette, and the A-State again after they had pressed the key to end the tape.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988)

The PANAS assesses Positive Affect (10 items), the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic and alert, and Negative Affect (10 items), general subjective distress subsuming aversive moods. Items are rated 1 (very slightly or not at all), 2 (a little), 3 (moderately), 4 (quite a bit), or 5 (very much). Both scales have high internal consistency, appropriate retest reliability, and adequate validity (Watson et al., 1988). Parents completed the PANAS pre- and post-vignette. Cronbach's alpha was .88 for both the PA and NA scales.

Demographics Questionnaire

We assessed youth gender, age, ethnicity, and number of people living in the home. We assessed parent gender, age, marital status, ethnicity, education, and total family income.

Manipulation Check Questionnaire

Participants completed a questionnaire after the description of the child in the vignette. Half of the participants heard a description portraying the child as anxious and half heard a description providing neutral information about the child. Participants rated the child's anxiety level using an anchored 7-point Likert Scale (1 = not at all anxious, 7 = extremely anxious).

Procedure

A phone-screen eliminated inappropriate cases (e.g., principle non-anxiety disorders for PAD, wrong age range for PNAD). At intake, a coordinator explained the procedure and entry was predicated on written parental informed consent and child assent. Parents completed a demographics questionnaire and separate interviews were conducted with parents and child. Immediately prior to the experiment, parents completed the A-Trait, A-State, and PANAS.

The study was a 2 (parent status) × 2 (assigned child anxiety status) between subjects randomized factorial design. Half of the PAD and PNAD participants were randomly assigned to hear a description of the child in the vignette as anxious, whereas the other half were randomly assigned to hear a description that provided neutral information. Parents, seated at a keyboard with headphones, were told the following and then the child was described:

“You will be listening to a taped interaction between a mother and child. The dialogue lasts about 5 minutes. Please listen closely to the following description of the child that you will hear on the tape.”

Anxious description: Jennifer is a 10 year-old girl who is currently in the 5th grade at a local public school. According to her parents, Jennifer worries about “everything and anything,” is troubled by anything new, and asks endless “what if” questions. She also has difficulty separating from her parents and acts very clingy with her mother. Jennifer worries a lot that that something bad might happen to her family or that she will be kidnapped. Her parents also report that she acts very shyly and seems to “lack confidence” in social situations, with both kids and adults. She has a lot of trouble starting conversations, speaking to new people, going to parties or social events, and being assertive.

Neutral description: Jennifer is a 10 year-old girl who is currently in the 5th grade at a local public school. She lives with her parents and two younger brothers, Alex and Evan. Her favorite subject is music and her least favorite subject is math. She gets average grades in school. Jennifer has several activities she is involved in, including soccer and girl scouts. She is going on a camping trip with her Girl Scout troop in the next few weeks. Jennifer also likes art projects and animals and spends a lot of time playing with her dog. Jennifer is not sure what she wants to be when she grows up, but has mentioned possibly being a veterinarian or an actress.

After hearing their scripts, participants completed the manipulation check and were then told:

“You will be listening to a taped interaction between Jennifer and her mother. The dialogue lasts about 5 minutes. We are interested in your own perspective about how the parent on the tape should respond to the child, Jennifer, in the situation. Your task is to listen to the tape and signal, by pressing the shift key on the keyboard front of you, when you think the mother should do what Jennifer is asking her to do. There is no right or wrong time to push the button, it is simply a matter of your choice. After you press the shift key and only after you press the shift key, please take off your headphones and I will come back in the room. Once you have filled out some questionnaires, we will give you the chance to listen to the rest of the tape if you so choose. Remember these important instructions - if you press the button, you're only going to do so once – at the point when you think the mother should do what the child, Jennifer, is asking her to do.”

After questions, participants put on the headphones and heard the vignette. The interaction ran until the key was pressed, at which point the headphones were removed. After ending the vignette, participants completed the A-State and PANAS.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Group Demographic Comparisons

The 124 parent participants did not significantly differ on marital status, age, race, or total family income. There was a significant Parent Status × Assigned Child Anxiety Status interaction on child age, F(1, 120) = 6.96, p < .01, η2 = .05 (medium effect). Simple main effects analyses indicated that within PAD, there was a difference between the anxious and neutral conditions on child age, with participants in the anxious condition being younger, F(1, 120) = 5.27 p <.05, η2 = .04 (medium effect). Within PNAD, no significant differences on child age were found. However, given the finding that child age was not significantly correlated with any DVs and the fact that covarying age did not impact results, it was not a covariate in subsequent analyses. Mothers and fathers participated, so t-tests examined for gender differences. Results indicated that mothers and fathers did not significantly differ on response latency or A-State, PANAS NA, or PANAS PA scores, so they were collapsed into “parents” for all analyses.

Parent Anxiety, Affect, and Emotional Arousal

Means and standard deviations for the parent pre and post questionnaires are in Table 12. There were significant main effects of parent status (PAD vs. PNAD) on A-State scores, F(1, 120) = 14.45, p < .001, η2 = .10 (medium to large effect) and on PANAS-NA scores, F(1, 120) = 9.35, p < .001, η2 = .07 (medium effect), indicating higher mean scores for PAD than PNAD pre-vignette. Given the differences at pre-vignette, pre A-State and PANAS-NA were used as covariates when applicable in later analyses. No significant differences were found on pre PANAS-PA scores. Correlations are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Pre- and Post-Vignette Parent Questionnaires

| PAD/Anxious | PAD/Neutral | PNAD/Anxious | PNAD/Neutral | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post |

| A-Trait | ||||||||

| M | 38.29 | - | 37.67 | - | 30.86 | - | 29.32 | - |

| SD | 9.24 | - | 8.93 | - | 7.63 | - | 6.38 | - |

| A-State | ||||||||

| M | 32.26 | 36.80 | 33.45 | 36.19 | 28.67 | 29.36 | 24.21 | 24.21 |

| SD | 10.93 | 10.92 | 10.83 | 11.22 | 8.79 | 9.25 | 5.26 | 5.62 |

| PANAS-PA | ||||||||

| M | 32.00 | 29.26 | 32.12 | 30.78 | 31.60 | 31.14 | 35.04 | 35.21 |

| SD | 7.01 | 7.55 | 8.37 | 9.03 | 6.80 | 7.77 | 6.95 | 7.35 |

| PANAS-NA | ||||||||

| M | 13.34 | 14.40 | 12.97 | 14.06 | 11.50 | 11.84 | 10.50 | 11.00 |

| SD | 5.72 | 5.60 | 4.26 | 5.22 | 2.30 | 1.86 | 1.00 | 1.78 |

Note. A-Trait = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory - Trait Version; A-State = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory - State Version; PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affectivity Scale – Positive Affectivity; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affectivity Scale – Negative Affectivity

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Between Pre- Vignette Parent Measures

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Response Latency | - | ||||

| 2. A-Trait | .05 | - | |||

| 3. A-State | .01 | .78** | - | ||

| 4. PANAS-PA | −.19* | −.37** | −.36** | - | |

| 5. PANAS-NA | −.03 | .63** | .70** | −.19* | - |

Note. A-Trait = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory - Trait Version; A-State = State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – State Version; PANAS-PA = Positive and Negative Affectivity Scale – Positive Affectivity; PANAS-NA = Positive and Negative Affectivity Scale – Negative Affectivity.

p < .05,

p < .01.

Manipulation Check

All 63 participants who heard the anxious description reported the child was anxious (≥ 5). All 61 participants who heard the neutral description reported the child was not anxious (≤ 3). The experimental manipulation was effective. Participants also rated the realism of the audio interaction. The mean rating of realism was 80.49 (SD = 19.66), with 100 being completely realistic. A 2 (parent status) × 2 (assigned child anxiety status) ANOVA indicated no significant main or interaction effects for parent status or assigned child anxiety status on ratings of realism.

Response Latency

The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 33. Across groups, response latency ranged from 32.74 – 338 seconds. The response latency distribution met the assumptions of normality (skewness = .888, kurtosis = −.466)4. To examine whether being the parent of a child with AD and being told a child is anxious influence parents' decisions to intervene and/or permit avoidance, a 2 (parent status) × 2 (assigned child anxiety status) analysis of variance (ANOVA) using response latency as the DV was conducted5. There was a significant main effect of assigned child anxiety status (anxious vs. neutral) on response latency, F(1, 120) = 5.91, p < .05, η2 = .05 (medium effect). There was also a significant Parent Status × Assigned Child Anxiety Status interaction with regard to response latency, F(1, 120) = 4.11, p < .05, η2 = .03 (small to medium effect)6. Simple main effects analyses indicated that within PNAD, there was a difference between the anxious and neutral child anxiety status conditions on response latency, with participants in the anxious condition exhibiting longer response latencies, F(1, 120) = 9.06, p <.01, f = .07 (medium effect). Within PAD, no significant differences on response latency between the anxious and neutral conditions were found7. The interaction is in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Response Latencies by Experimental Group

| Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PAD/Anxiousa | PAD/Neutralb | PNAD/Anxiousc | PNAD/Neutralc |

| M | 162.98 | 156.78 | 207.79 | 136.64 |

| SD | 79.83 | 82.32 | 98.38 | 78.43 |

Note. PAD = Parents of Anxiety-Disordered Children; PNAD = Parents of Non-Anxiety Disordered Children.

n = 35.

n = 33.

n= 28.

(M = 166.18; SD = 87.07). The response latency distribution met the assumptions of normality (skewness = .888, kurtosis = −.466)2.

Figure 1.

Interaction between parent status and assigned child anxiety status on response latency.

State and Trait Anxiety

To examine whether being the parent of a child with AD and being told a child is anxious influence parents' state anxiety, a 2 (parent status) × 2 (assigned child anxiety status) ANCOVA using post A-State as the DV and pre A-State as the covariate was performed. A significant main effect for group was observed with PAD scoring higher than PNAD, F(1, 120) = 14.26, p <.001, η2 = .10 (medium to large effect). No significant interactions were found. The Pearson product-moment correlation between trait anxiety and response latency was r = .05, p = .59.

Emotional Response

To examine whether being the parent of a child with AD and being told a child is anxious influence negative affect, a 2 (parent status) × 2 (assigned child anxiety status) ANCOVA using post PANAS-NA as the DV and pre PANAS-NA as the covariate was performed. A significant main effect for group was observed with PAD scoring higher than PNAD, F(1, 120) = 7.96, p <.01, η2 = .04 (medium effect). No significant interactions were found. To examine whether being the parent of a child with AD and being told a child is anxious influence parents' positive affect, a 2 (parent status) × 2 (assigned child anxiety status) × 2 (time) repeated measures ANOVA was performed, using the PANAS-PA. We found a significant main effect for time, F(1, 119) = 12.79, p <.001, η2 = .09 (medium to large effect) and a significant Parent Status × Time interaction, F(1, 119) = 9.60, p < .01, η2 = .08 (medium to large effect). Simple main effects analyses indicated that within PAD, there was a difference between pre and post on PA, with lower scores on post PANAS-PA, F(1, 119) = 25.31, p <.001, η2 = .21 (large effect). Within PNAD, there was no significant difference on PA between pre and post scores.

DISCUSSION

PNAD participants took significantly longer to respond and therefore, to give in to the child's requests, when they were told that the child was anxious than not. There were no significant differences in the response latencies of PAD according to whether they were told the child was anxious. These results indicate that PNAD did not support avoidant behavior when the child's history indicated that it was important to refrain from intervention. PNAD parents responded more quickly when they were provided with neutral information, suggesting flexibility in their parenting dependent upon the child. PAD, on the other hand, responded similarly regardless of the child's assigned anxiety status, suggesting a more rigid parenting style that does not vary according to the child's characteristics, which might be more adaptive. It is notable that PNAD took longer to respond, thereby not giving in, when they thought the child was anxious: one interpretation is that by waiting, the PNAD participants effectively discouraged avoidant behavior. Following this logic, the PNAD who heard a neutral description responded earlier, as for them, there was no indication in the child's history that it was crucial to face the task. Alternatively, perhaps PNAD were simply better able to discriminate valid requests for help; they understood that a non-anxious child asking for help may truly need it, whereas an anxious child might simply be requesting excessive reassurance and parental involvement. PAD might have been less able to differentiate between appropriate and excessive requests for help.

The finding that PNAD, rather than PAD, accounted for the interaction effect is potentially important. Given previous research, PAD were expected to be more encouraging of avoidance (Barrett et al., 1996; Hudson & Rapee, 2001), and thus, to respond more quickly than PNAD, and PAD were expected to respond more quickly when they perceived the child as anxious. However, it was the PNAD who significantly differed in their responses depending upon the child's assigned anxiety status. Although using a different method, the present results agree with those of Hudson and Rapee (2002), with a modification. They found that parents were equally involved with anxious children and non-anxious siblings and that mothers of anxious children were more involved overall than mothers of non-anxious children; thus, they posited that over-involvement may not be a response to the child's temperament, but a stable parenting style. The current results suggest that what is central, perhaps, may not be the over-involvement, but that this behavior remains stable when it might be more adaptive to vary.

PAD became more anxious and exhibited increased negative and decreased positive affect post-vignette (even after controlling for initial differences), regardless of the child's assigned anxiety status (whereas PNAD did not), indicating that listening to a child in an anxious situation was more stressful for PAD than for PNAD. Turner and colleagues (2003) also found that although anxious parents did not overly restrict their children, they reported higher distress when children were engaged in activities and were more concerned about everyday events. We believe that PAD, who became more anxious and negative and less positive, rescued their children because they could not tolerate their child's distress, as in previous research (e.g., Cheron et al., 2009; Woodruff-Borden et al., 2002). Parents who are limited in their emotion regulation abilities and therefore avoid negative emotional experiences may also be less adaptive and flexible when addressing their child's emotions. The significant increase in state anxiety and emotional changes for PAD is consistent with the idea that arousal affects parenting and that parents are unable to tolerate their own distress at watching their children (Tiwari et al., 2008). State anxiety involves intolerance of ambiguity and rigid behavior and is related to experiential avoidance, likely explaining PAD's inflexible parenting. This rigidity is a probable reaction to feeling low perceived control and/or an attempt to avoid negative emotion (e.g., Cheron et al., 2009; Wheatcroft & Creswell, 2007). Possibly, PNAD are flexible and adaptive in their parenting and did not reinforce avoidance because they were unencumbered by anxious arousal.

The experimental method, the objective definition of parenting behavior, diagnostics, and measurement of parent anxiety and emotion were study strengths. The assessment of parental psychopathology by self-report and the absence of an alternate psychopathology comparison, which would have permitted an examination of the specificity of the findings, are limitations. Other limitations are that we do not have data on (a) siblings and cannot eliminate the possibility that PNAD have other children with anxiety disorders and (b) whether PAD families participated in prior treatment and cannot rule out that parents could be applying learned strategies. We can confirm, however, that they had not yet received nor been socialized to our CBT. Finally, generalizability may be limited: parents were given a forced choice (giving in to child's demands or not) when they might typically have other options (e.g., positive interpretations, praise). Questions for future research include the following: although experts and parents rated the vignette as realistic, it would be prudent to evaluate the realism in other geographic locations and parent samples. Also, given that we did not gender-match the vignettes for each child (all parents listened to an interaction involving a female child), it would be interesting to investigate whether parents might react differently based on child gender. Finally, because we did not evaluate the benefits of delaying pressing the button (permitting opportunities for exploration and habituation) vs. the risk of reinforcing a tantrum by pressing the button after negative behavior, this remains an interesting question for further investigation.

The present results have clinical implications. Efficacious treatments for anxious youth include the child engaging in exposure tasks and using coping skills and some treatments include parents (Cobham, Dadds, & Spence, 1998; Kendall et al., 2008). The current results suggest it would be useful to help parents tailor their behavior to the child and to the situation. Parents could benefit from instruction in how to cope with their own anxiety/arousal, particularly when observing their child in an anxious situation. If parents are able to tolerate their own distress, they may be better equipped to refrain from intervening and reinforcing avoidance.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology (APA Division 53) Student Research Award, the Pennsylvania Psychological Foundation Education Award, and the graduate student research initiative from the CAADC, awarded to Sasha G. Aschenbrand. This research was also supported in part by NIMH grant MH59087 and facilitated by grants MH063747 and MH086438 awarded to Philip C. Kendall.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/ccp

Transcript is available from the first author. Actors recruited by advertisement through community theater organizations performed the recorded script.

Analyses were conducted to determine whether there were differences on each of the DVs (response latency, A-State, A-Trait, PANAS-NA, and PANAS-PA) between participants from families in which both parents participated in the study and participants from families in which only one parent participated in the study. Results indicated that there were no significant differences in any of the DVs between these two groups of participants.

Analyses were conducted to determine whether there were differences on response latency between participants with male vs. female children, given that all participants listened to a female child in the vignette. Results indicated that there were no significant differences in response latency according to child gender.

Although the response latency data was determined to fit a normal distribution, analyses were also run using a log-transformation of response latency scores, which provided scores that most closely approximated a normal distribution. The pattern of results was completely comparable, so we decided to use the untransformed data for purposes of further analyses.

Analyses were conducted to determine whether there were differences between parents who pressed the button and those who refrained from pressing the button for the entire vignette (N = 13). Results indicated that there were no significant differences between parents who pressed the button and those who did not.

These analyses and all subsequent were also performed eliminating the parents of the 6 children in the PNAD group who met criteria for ADHD. All analyses found the same pattern of results with or without these participants; therefore, the participants were retained in subsequent analyses for purposes of sustaining adequate power.

Within the PAD group, analyses examined whether there were significant differences in response latency by the principal anxiety diagnosis of each parent's child or by whether each parent's child met criteria for ADHD or ODD. Results indicated no significant differences in response latency by principal anxiety diagnosis or by presence/absence of a disruptive behavior diagnosis. For the PNAD group, similar analyses found no significant differences in response latency between parents of children with/without a disruptive behavior diagnosis.

REFERENCES CITED

- Barrett PM, Rapee RM, Dadds MM, Ryan SM. Family enhancement of cognitive style in anxious and aggressive children: Threat bias and the FEAR effect. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1996;24:187–203. doi: 10.1007/BF01441484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein M, Ginsburg GS. The effect of parental modeling of anxious behaviors and cognitions in school-aged children: An experimental pilot study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:506–515. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheron DM, Ehrenreich JT, Pincus DB. Assessment of parental experiential avoidance in a clinical sample of children with anxiety disorders. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2009;40:383–403. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0135-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Albano AM, Barlow DH. Cognitive processing in children: Relation to anxiety and family influences. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cobham VE, Dadds MR, Spence SH. The role of parental anxiety in the treatment of childhood anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:893–905. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobham VE, Dadds MR, Spence SH. Anxious children and their parents: What do they expect? Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1999;28:220–231. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2802_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell C, Schniering CA, Rapee RM. Threat interpretation in anxious children and their mothers: Comparison with nonclinical children and the effects of treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1375–1381. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco LA, Blackledge JT, Coyne LW, Ehrenreich J. Integrating acceptance and mindfulness into treatments for child and adolescent anxiety disorders: Acceptance and commitment therapy as an example. In: Orsillo SM, Roemer L, editors. Acceptance and mindfulness-based approaches to anxiety. Springer; New York: 2005. pp. 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hedtke KA, Kendall PC, Tiwari S. Safety-seeking and coping behavior during exposure tasks with anxious youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15374410802581055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Rapee RM. Parent-child interactions and anxiety disorders: An observational study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2001;39:1411–1427. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JL, Rapee RM. Parent-child interactions in clinically anxious children and their siblings. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:548–555. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3104_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Finch AJ, Jr., Auerbach SM, Hooke JF, Mikulka PJ. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: A systematic evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1976;44:406–412. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.44.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortlander E, Kendall PC, Panichelli-Mindel SM. Maternal expectations and attributions about coping in anxious children. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1997;11:297–315. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(97)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Albano AM. Advances in the assessment of pediatric anxiety disorders. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;20:213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Gross AM, Adams HE. The effect of alcohol on the responses of sexually coercive and non-coercive men to an experimental rape analogue. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 1999;11:131–145. doi: 10.1177/107906329901100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Meesters C, Merckelbach H, Hulsenbeck P. Worry in children is related to perceived parental rearing and attachment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:487–497. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM. The development of generalized anxiety. In: Vasey MW, Dadds MR, editors. The developmental psychopathology of anxiety. Oxford University Press; New York: 2001. pp. 481–503. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Albano AM. Manual for the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child version. Graywind Publications; Albany, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Eisen AR. Age differences in the reliability of parent and child reports of child anxious symptomatology using a structured interview. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:117–124. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Nelles WB. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1988;27:772–778. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198811000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Piña AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnosis with the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:937–944. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200108000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Manual. Mind Garden; Palo Alto, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley MA, Beck JG, Zebb BJ. Psychometric properties of four anxiety measures in older adults. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:827–838. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Podell JC, Martin ED, Mychailyszyn MP, Furr JM, Kendall PC. Experiential avoidance in the parenting of anxious youth: Theory, research, and future directions. Cognition and Emotion. 2008;22:480–496. [Google Scholar]

- Turner SM, Beidel DC, Roberson-Nay R, Tervo K. Parenting behaviors in parents with anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2003;41:541–554. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whaley SE, Pinto A, Sigman M. Characterizing interactions between anxious mothers and their children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:826–836. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatcroft R, Creswell C. Parents' cognitions and expectations about their pre-school children: The contribution of parental anxiety and child anxiety. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2007;25:435–441. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff-Borden J, Morrow C, Bourland S, Cambron S. The behavior of anxious parents: Examining mechanisms of transmission of anxiety from parent to child. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:364–374. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]