Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate if two pharmacological agents, Tempol and D-methionine (D-met), are able to prevent oral mucositis in mice following exposure to ionizing radiation ± Cisplatin.

Methods and Materials

Female C3H mice, ~8 weeks old, were irradiated with five fractionated doses ± Cisplatin to induce oral mucositis (lingual ulcers). Just prior to irradiation and chemotherapy, mice were treated, either alone or in combination, with different doses of Tempol (by intraperitoneal, ip, injection or topically, as an oral gel) and D-met (by gavage). Thereafter, mice were sacrificed, tongues harvested and stained with a solution of Toluidine Blue. Ulcer size and tongue epithelial thickness were measured.

Results

Significant lingual ulcers resulted from 5 × 8 Gy radiation fractions, which were enhanced with Cisplatin treatment. D-met provided stereospecific partial protection from lingual ulceration after radiation. Tempol, via both routes of administration, provided nearly complete protection from lingual ulceration. D-met plus a suboptimal ip dose of Tempol also provided complete protection.

Conclusions

Two fairly simple pharmacological treatments were able to markedly reduce chemoradiation-induced oral mucositis in mice. This proof of concept study suggests that Tempol, alone or in combination with D-met, may be a useful and convenient way to prevent the severe oral mucositis that results from head and neck cancer therapy.

Keywords: chemoradiation, side effects, oral mucositis, Tempol, D-methionine

INTRODUCTION

Oral mucositis is a common side effect of using cytotoxic chemotherapy to treat most cancers and, in particular, of radiation therapy ± chemotherapy for head and neck cancers (1–3). It is complex in its etiology (1), debilitating for patients (2,3), expensive to manage (4,5) and can confound and limit cancer therapy (1). Present treatment for therapy-induced oral mucositis is primarily palliative, with one notable exception, the use of recombinant keratinocyte growth factor (palifermin, Kepivance®), which is limited for use in patients with hematological malignancies who receive conditioning regimens in preparation for stem cell transplant., i.e., ~4% of the at-risk population (1). Kepivance® is not approved for treating oral mucositis resulting from the treatment of other malignancies. Indeed, the evidence for its efficacy in treating oral mucositis occurring during head and neck cancer therapy is weak (e.g., 6). Additionally, Kepivance® is delivered by intravenous (iv) injections, which are inconvenient, uncomfortable and expensive. The treatment of oral mucositis can be reasonably considered “an un-met need with a high priority for the development of an effective treatment” (1). Accordingly, there recently has been increased research focused on the pathogenesis of oral mucositis to identify more appropriate targets for therapy (1), and test alternative strategies for this condition (e.g., 7–9).

Previously, we have shown that the stable nitroxide, Tempol (4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-N-oxyl) is a useful radioprotector both in vitro and in vivo (e.g., 10,11) and can significantly diminish the occurrence of radiation-induced salivary gland hypofunction (xerostomia; e.g., 12). Herein, we examined the utility of Tempol, administered either via intraperitoneal, ip, injection or as an oral gel, for preventing oral mucositis after head and neck irradiation ± Cisplatin. In addition, we compared its efficacy with that of D-met, and examined using D-met in combination with a suboptimal dose of Tempol.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Chemicals and experimental animals

Tempol was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The gel form of Tempol was prepared by Starks Associates, Inc., (Buffalo, NY), by adding Tempol to a 1.5% hydroxyethyl cellulose base gel solution (final Tempol concentration, 470 mM). Cisplatin was from the NIH Veterinary Pharmacy. Female C3H mice (NCI Animal Production Area; Frederick, MD) were used as described previously (9).

Animal radiation

The head and neck area was irradiated as reported previously (9,12). Initial experiments used a single dose of 22.5 Gy, however, most data employed a fractionated scheme, five fractions of 6, 7 or 8 Gy, on consecutive days, as described (9). After irradiation, animals were housed (4/cage) in a climate and light controlled environment and allowed free access to solid, soft food, Transgel (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) and water. Animals that received five fractions of 8 Gy and Cisplatin were given a nutritional supplement by gavage from days 5–10.

Drug treatments

Tempol (275 or 137.5 mg/kg) was either injected intraperitoneally (ip) or administered as 100 µl of the above gel topically in the oral cavity, ~10 min prior to each irradiation fraction. D-met (150 mg/kg) or L-met (150 mg/kg) was prepared by dissolving 0.3g of D-met (M9375; Sigma, St Louis MO) in 5ml of 0.1N NaOH and adding 5ml of 0.1N HCl. The pH was checked, adjusted to ~7.0 if needed, after the solution was prepared, and was delivered by gavage. Cisplatin was administered by ip injection (2.5 mg/kg) on days 1, 3 and 5 of the irradiation regimen.

Demonstration of mucositis

At the end of each experiment (time-point dependent on radiation type [single, fractionated] and end-point measure [ulcer size, epithelial thickness]; see Figure legends for more details), mice were sacrificed in a carbon monoxide chamber. Tongues were excised and then stained in a solution of 1% Toluidine Blue in 10% acetic acid, as described (9), to visualize mucositis (lingual ulcers). Thereafter, tongues were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin. Three µm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), examined microscopically and ulcer size and epithelial thickness measured as described previously (9).

Radiation re-growth delay studies

SCC VII/SF (SCC) tumor cells were derived from a spontaneous squamous cell cancer and propagated in mice. For radiation re-growth delay studies, 2 × 105 viable SCC VII cells suspended in 100 ml PBS were injected into the subcutaneous space of the right hind leg of 7–9 week old female C3H mice and followed, as described (9,12). Tumor measurements were made 2–3 times per week.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses employed SigmaStat version 2.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and Excel (Microsoft, Bellevue, WA) software. Generally, one-way analyses of variance, followed by either a Bonferroni comparison or Student-Newman-Keuls test, as appropriate, or a paired t-test, were employed (see figure legends). For studying the effect of agents on tumor growth, data were fit using an exponential growth equation. The tumor growth time (days) for control animals was calculated, and then subtracted from all treated groups. Standard deviations (SD) of derived values (treated and control) were obtained using the propagation of error formula (13) and then SDs were used to calculate the Students t-test and p-values for differences between various groups (14).

RESULTS

Studies with a single irradiation dose

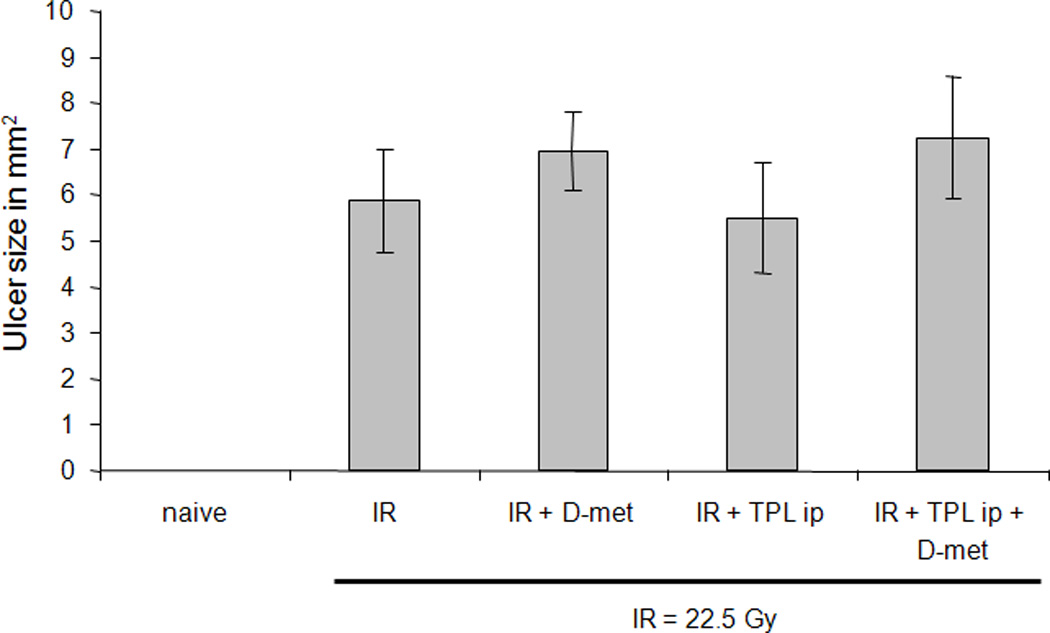

Initially, we used a single 22.5 Gy dose, which consistently led to severe ulceration on the dorsum of all mouse tongues (Fig. 1). Administration of D-met (150 mg/kg by gavage) or Tempol (275 mg/kg; ip) just prior to irradiation, alone or in combination, was unable to prevent this ulceration (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of D-met and Tempol (TPL) on lingual ulcer size following single dose irradiation (IR). Mice were administered D-met (150 mg/kg, gavage) or Tempol (275 mg/kg, ip) and thereafter irradiated with 22.5 Gy. Animals were sacrificed at day 7, their tongues removed, examined for ulceration using Toluidine Blue, and ulcer size measured, as described in Methods and Materials. Data are mean values ± SEM (n=7 or 8/group).

Fractionated dose irradiation studies

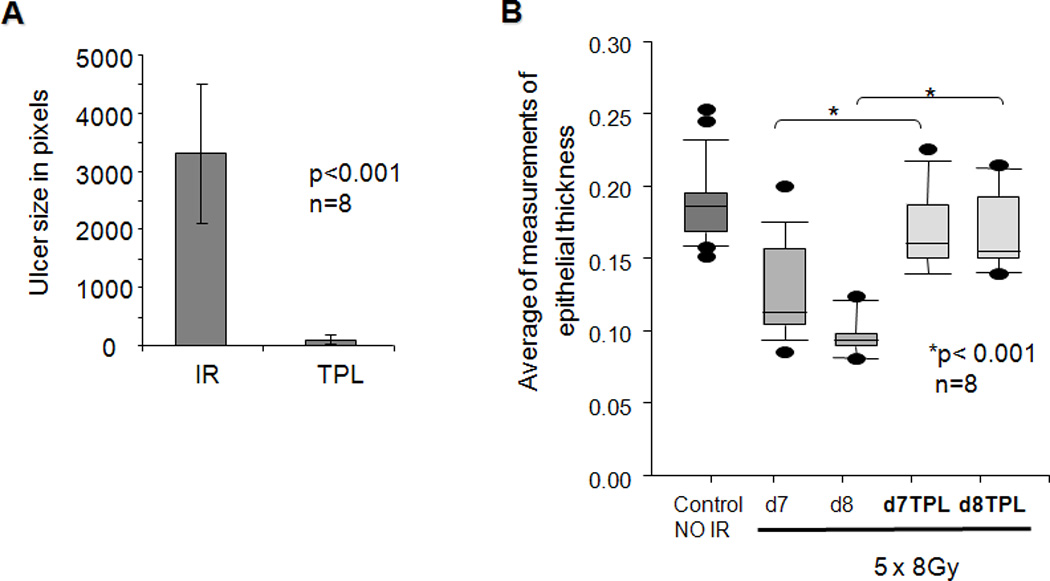

As previously demonstrated, the 5×8 Gy fractionated scheme leads to a severe ulceration on the dorsum of mouse tongues within 8–10 days (9; Fig. 2; see also supplemental Fig. 1 for H&E staining), and is a more clinically relevant radiation mucositis model. Tempol administration (275 mg/kg; ip) just prior to each radiation dose provided almost complete protection from radiation-induced mucositis, 85–95%, measured by both ulcer size and epithelial thickness (Fig. 2A, B).

Fig. 2.

Effect of Tempol (TPL) on ulcer size and epithelial thickness following fractionated irradiation (IR). Mice were irradiated (8 Gy) for five consecutive days. A. Animals (n=8/ group) were sacrificed at day 10 and their tongues removed and examined for ulceration with Toluidine Blue. Lingual ulcer size was quantified using NIH Image J software (mean values ± SEM). Ulcer size in the two groups was significantly different (Student’s t test; p<0.001). B. Epithelial thickness on the tongue dorsum prior to frank ulceration, i.e., on days 7 or 8 (n=8/group). Data are box plots. The lower boundary of the box represents the 25th percentile of values, while the upper boundary represents the 75th percentile. The horizontal line within the box represents the median value. Closed circles above and below the boxes represent out of range values. “*” indicates values significantly different from the non-Tempol irradiated results (p<0.001), following an analysis of variance and Bonferroni pair wise comparison.

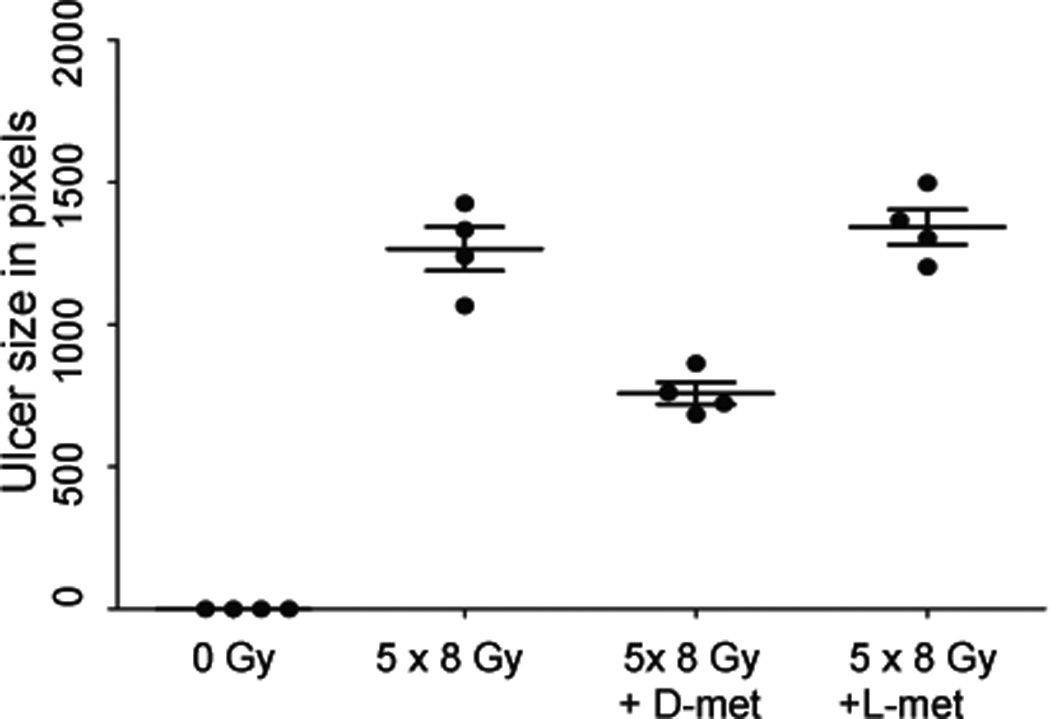

Pretreatment of mice with D-met, also yielded significant protection with this fractionated radiation scheme (Fig. 3). However, the protective effect was partial and less than that of Tempol, ~50–60%. The reduction in ulcer size mediated by D-met was dose-dependent (not shown) and stereo-specific (Fig. 3), with maximum protection at 150 mg/kg, the highest dose we were able to administer. L-met, at this dose, was completely ineffective in preventing ulcer formation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of D-met on lingual ulcer size following fractionated irradiation was stereoselective.. Mice were irradiated (8 Gy) for five consecutive days and treated as indicated with D-met or L-met. Animals were sacrificed on day 10, their tongues removed and examined for ulceration using Toluidine Blue. Lingual ulcer size (n=4) was quantified using NIH Image J software, as described in reference 9. Data from one of two similar experiments are shown as scatter plots (mean values ± SEM). An analysis of variance, followed by a Bonferroni pair wise comparison, indicated results with irradiated groups treated with D-met and L-met were significantly different (p<0.001).

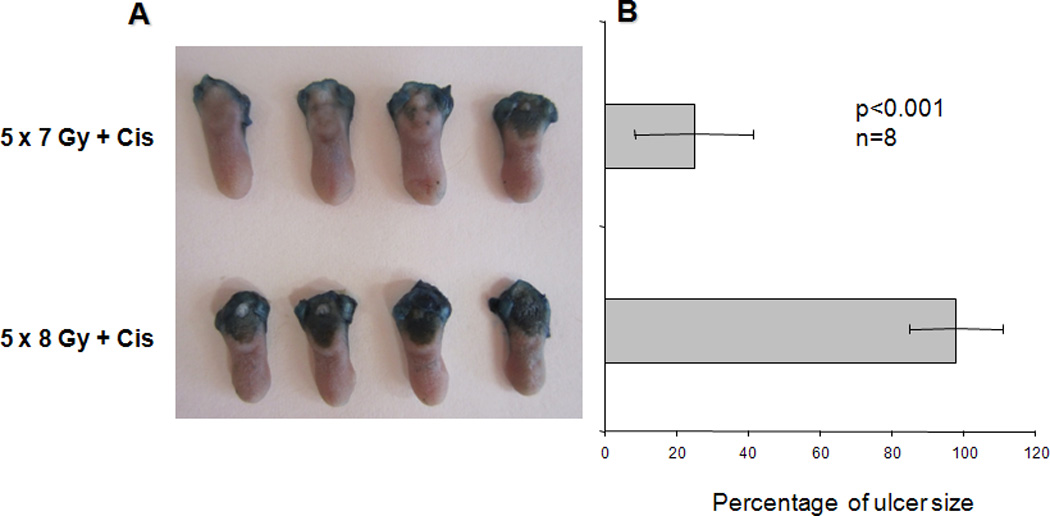

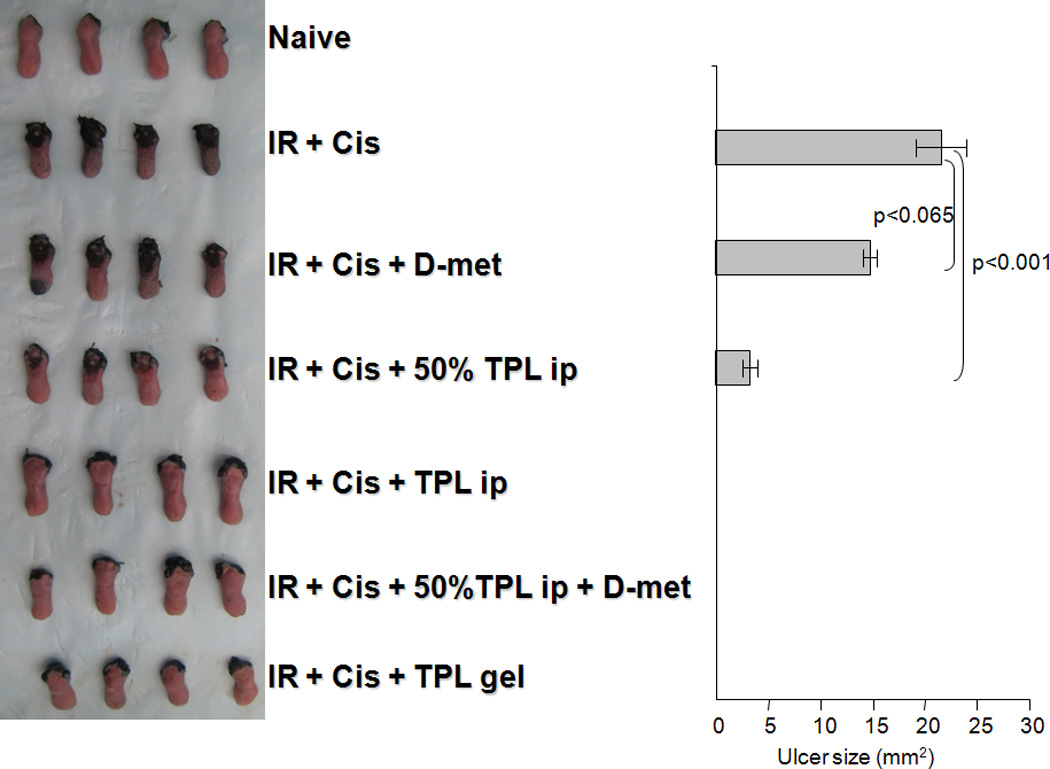

Fractionated irradiation studies with Cisplatin

Since chemotherapy is used with radiation increasingly for treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (e.g., 11,15), we next studied mice that received both fractionated irradiation (five daily doses of 6, 7 or 8 Gy), plus Cisplatin (2.5 mg/kg, on radiation days 1, 3 and 5). As shown (Fig. 4), lingual ulcerations were radiation dose-dependent at this constant dose of Cisplatin; absent at t 5×6 Gy (not shown), modest at 5×7 Gy (~20% maximum) and severe at 5×8 Gy (maximum, i.e., 100%). If animals were pretreated with Tempol (275 mg/kg. ip) prior to each radiation/ Cisplatin dose, no lingual ulcers were formed, i.e., essentially 100% protection from frank mucositis (Fig. 5). Tempol in gel form intra-orally (16) also provided almost complete protection (~95%). D-met alone, administered at 150 mg/kg just prior to each irradiation and Cisplatin dose, did not significantly reduce lingual ulcers (Fig. 5; p=0.065). However, the same dose of D-met, with submaximal Tempol (137.5 mg/kg, ip; 20), were additive and led to complete mucosal protection (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Effect of Cisplatin on radiation-induced oral mucositis. A. Mice (n=8/group) were irradiated (8 Gy) for five consecutive days. Animals also received ip injections of Cisplatin (2.5 mg/kg; Cis) on days 1, 3 and 5. Animals were sacrificed on day 10 and their tongues removed and examined for ulceration using Toluidine Blue. Tongues from four mice are shown for the 7 Gy and 8 Gy fractionated radiation dose groups. B. Quantification of lingual ulcer size in the 7 and 8 Gy radiation groups (6 Gy/day for five days + Cis showed no lingual ulcers) was done using NIH Image J software (mean values ± SEM; n=8/group). Ulcer size was normalized to 100% for the 5×8 Gy-group. Differences between the two groups were significant (Student’s t test; p<0.001).

Fig. 5.

Effect of Tempol (TPL) ± D-met on oral mucositis resulting from fractionated irradiation (IR) and Cisplatin (Cis). Left panel. Mice were irradiated (8 Gy) for five consecutive days, with Cisplatin treatment on days 1,3 and 5. A naive control group was also studied. Animals were sacrificed on day 10 and their tongues removed and examined for ulceration using Toluidine Blue. Tempol was administered daily via ip injection (275 mg/kg or 137.5 mg/kg, i.e., 50%) or topically in the mouth as a gel (470 mM in 1.5% hydroxyethyl cellulose) just prior to irradiation. D-met was administered daily (150 mg/kg, gavage), also just prior to irradiation. Tongues from four mice in one of two similar experiments are shown. Note the blue area of the anterior tongue, first sample in the IR+Cis+D-met group, was damaged during surgical removal, i.e., it does not represent ulceration. Right panel. Quantification of lingual ulcer size in the animals from each treatment group of the experiment shown in “A”, was done using NIH Image J software (mean values ± SEM). Comparable results were found with the other experiment. An analysis of variance, followed by a Bonferroni pair wise comparison, indicated a significant difference in ulcer size between the treatment groups indicated, i.e., p<0.001, between irradiation and Cisplatin treatment ± 50% TPL treatment. Also, differences were significant between the irradiation and Cisplatin treatment ± D-met groups and all other study groups (p<0.001). Differences between the irradiation and Cisplatin treatment ± D-met groups were not significant (p=0.065).

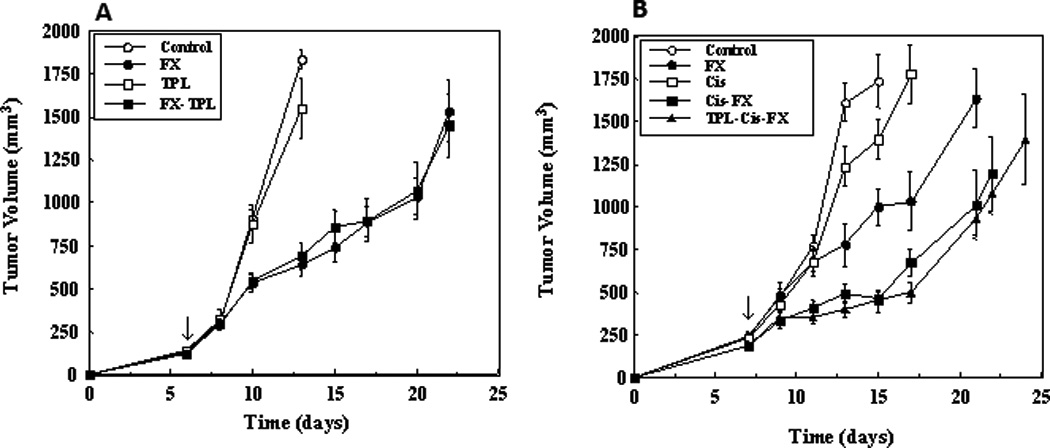

Absence of tumor protection by Tempol and D-met

As previously reported (12), Tempol application before each of five daily radiation doses did not protect against radiation-induced tumor re-growth delay (Fig. 6A). Cisplatin treatment alone had a modest, not significant effect on tumor growth. Fractionated radiation treatment alone resulted in tumor growth delay; however, the addition of Cisplatin to fractionated radiation resulted in a significant growth delay. Tempol treatment did not influence the Cisplatin-mediated enhancement of the radiation-induced tumor re-growth delay. The time for tumors to reach 3 times the initially measured tumor volume relative to the control for fractionated radiation, Cisplatin + fractionated radiation, and the tri-modality was 14.3 (p = 0.04), 18.6 (p < 0.0001), and 19.2 (p < 0.0001) days, respectively. There was no significant difference between the Cisplatin-fractionated radiation and Cisplatin-fractionated radiation-Tempol groups (Figure 6B). Cisplatin ± Tempol with radiation resulted in no untoward toxicity. Animal weights throughout the study for both groups were similar to untreated controls. D-met at the 150mg/kg dose± radiation showed no effect on tumor growth (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Tempol has no effect of SCC VII tumor growth ± radiation ± Cisplatin. Mice were injected with SCC VII tumor cells as described in Methods and Materials and then irradiated (3 Gy for five consecutive days; n=4/group) or not. A. Effect of fractionated radiation (daily 3 Gy fractions × 5) ± Tempol treatment (275 mg/kg, ip injection 5 min before each radiation fraction) on SCC tumors. Arrow indicates start of treatments. B. Effect of fractionated radiation (daily 3 Gy fractions × 5) ± Cisplatin ± Tempol treatment on SCC tumors. Arrow indicates start of treatments. Tumor growth data were fit using an exponential growth equation, tumor growth time (days) for control animals calculated, and then subtracted from all treated groups. Standard deviations (SD) of the derived values (treated and control) were obtained using the propagation of error formula (13) and used to calculate the Students t-test and p-values for the differences between the various groups (14). There was no effect of Tempol treatment ± Cisplatin on tumor size.

Discussion

Oral mucositis, resulting from radiation and chemoradiation protocols, is a highly significant side effect of cancer treatment. It reduces patient quality of life, affects nutritional intake, leads to oral and systemic infections, as well as limits therapy (1–3). At present, there is a single radiation mitigator approved for use with oral mucositis (hKGF, palifermin, Kepivance®; e.g., 17), and no radioprotectors. Kepivance® is only approved for patients being treated for hematologic malignancies and receiving conditioning regimens in preparation for a stem cell transplant. It is delivered by intravenous injection, and thus is inconvenient and uncomfortable. In addition, as a recombinant growth factor, it is expensive, adding to the significant costs of oral mucositis (4,5). Amifostine, a FDA-approved radioprotector for radiation-induced xerostomia, does not significantly reduce oral mucositis in patients undergoing chemoradiation (e.g., 18), There is clearly a need for additional agents to prevent and mitigate the development of oral mucositis in patients during head and neck cancer treatment. (1,6)

Accordingly, we examined the ability of two pharmacological agents, Tempol and D-met, to prevent oral mucositis induced by radiation ± Cisplatin. Both agents have previously been shown in rodents to be useful to prevent radiation-induced damage to normal oral tissues: Tempol for salivary gland hypofunction (12) and D-met for oral mucositis (7). The positive results described herein suggest a potentially novel clinical application of Tempol, i.e., preventing radiation-induced oral mucositis, and generally confirm the reported utility of D-met for this condition (7). Additionally, we demonstrate that their usage together appears additive. Furthermore, we show that Tempol administered topically as an oral gel is almost as effective in preventing oral mucositis as ip-administered Tempol. Finally, our findings suggest that using Tempol or Tempol + D-met may have applicability with the clinical chemoradiation protocols that are used more frequently for head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (11,15).

Tempol is a stable nitroxide that long has been shown to protect normal cells from radiation damage (10,11). Importantly, we previously have shown that Tempol does not affect the growth of tumor ± radiation (12), confirmed herein, and also shown herein that Tempol has no effect on Cisplatin-mediated enhancement of radiation-induced tumor re-growth delay. Earlier studies reported that Tempol gave no radiation protection using the HT29 xenograft model (radiation tumor re-growth delay; 12) or for RIF-1 murine tumors using a radiation tumor re-growth assay and TCD50 (tumor cure dose in 50% of mice; 19)

Tempol has been used as a topical agent in a phase I clinical trial for radiation-induced alopecia with mild toxicity and considerable efficacy (20), and now is being studied in a phase II trial (http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00801086?term=tempol&rank=1). D-met is the stereoisomer of the essential amino acid L-met, and appears to function as a radioprotector independent of free radical scavenging (7), i.e., quite different from Tempol, which may account for the additive effect observed herein. D-met reportedly provides selective protection for non-transformed, versus transformed, cells (7), in keeping with our observation that it does not affect tumor growth ± radiation. The use of D-met in human studies resulted in mild-moderate side effects, but it appeared beneficial for limiting the occurrence of severe oral mucositis (8). Racemic mixtures of D- and L-met have long been used for acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity (e.g., 21).

Given the present results, it seems reasonable to posit that Tempol, alone or in combination with D-met, may have clinical benefits. Tempol, a radioprotector, and D-met, a mechanistically different radioprotector, in theory offer the prospect for an easily administered (oral topical, ingestion), convenient and minimally expensive treatment for preventing oral mucositis. Given the high burden of cost associated with oral mucositis (4,5), and its considerable impact on a patient’s quality of life (2,3), the importance of developing effective radioprotectors to prevent oral mucositis is clear (1). Interestingly, almost all preclinical radiation- and chemoradiation-induced oral mucositis studies, like the present study, have been conducted in rodents. We suggest that the next step should be to develop a useful, large animal, preclinical model of oral mucositis for testing Tempol ± D-met. If Tempol ± D-met is effective, safe and scalable from rodent studies, there will be ample justification for a definitive clinical trial.

Highlights.

Oral mucositis is a common side effect of radiation therapy ± chemotherapy for head and neck cancers. We studied the utility of Tempol in preventing oral mucositis after head and neck irradiation ± Cisplatin in mice. Also, we compared its efficacy with that of D-methionine. Tempol provided nearly complete protection from lingual ulceration, while D-methionine provided stereospecific partial protection. D-methionine plus a suboptimal dose of Tempol also provided complete protection. Our findings suggest these pharmacological treatments may be a useful in preventing severe oral mucositis.

Supplementary Material

Shown are three micrographs presenting the histological appearance of normal lingual epithelium (naïve), ulcerated lingual epithelium (IR only, with the brackets delineating the ulcer) and Tempol protected lingual epithelium (IR + Tempol, ip, intraperitoneal injection). The double-headed arrow indicates the area measured for epithelial thickness. The dorsal epithelial surface is shown.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The Divisions of Intramural Research of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research and National Cancer Institute supported this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Notification

No actual or potential conflicts of interest exist for all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sonis ST. Mucositis: The impact, biology and therapeutic opportunities of oral mucositis. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein JB, Beaumont JL, Gwede CK, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of the oral mucositis weekly questionnaire-head and neck cancer, a patient-reported outcomes questionnaire. Cancer. 2007;109:1914–1922. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elting LS, Keefe DM, Sonis ST, et al. Patient-reported measurements of oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy with and without chemotherapy. Cancer. 2008;113:2704–2713. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nonzee NJ, Dandade NA, Markossian T, et al. Evaluating the supportive care costs of severe radiochemotherapy-induced mucositis and pharyngitis. Cancer. 2008;113:1446–1452. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy BA, Beaumont JL, Isitt J, et al. Mucositis-related morbidity and resource utilization in head and neck cancer patients receiving radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Management. 2009;38:522–532. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sonis ST. Efficacy of palifermin (keratinocyte growth factor-1) in the amelioration of oral mucositis. Core Evidence. 2009;4:199–205. doi: 10.2147/ce.s5995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vuyyuri SB, Hamstra DA, Khanna D, et al. Evaluation of D-methionine as a novel oral radiation protector for prevention of mucositis. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2161–2170. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamstra DA, Eisbruch A, Naidu MUR, et al. Pharmacokinetic analysis and phase 1 study of MRX-1024 in patients treated with radiation therapy with or without Cisplatinum for head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2666–2676. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng C, Cotrim AP, Sunshine AN, et al. Prevention of radiation-induced oral mucositis after adenoviral vector-mediated transfer of the keratinocyte growth factor cDNA to mouse submandibular glands. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4641–4646. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell JB, DeGraff W, Kaufman D, et al. Inhibition of oxygen-dependent radiation-induced damage by the nitroxide mimic, Tempol. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;289:62–70. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90442-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Citrin D, Cotrim AP, Hyodo F, et al. Radioprotectors and mitigators of radiation induced normal tissue injury. The Oncologist. 2010;15:360–371. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cotrim AP, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K-I, et al. Differential radiation protection of salivary glands versus tumor by Tempol with accompanying tissue assessment of Tempol by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4928–4933. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bevington PR. Data Reduction and Error Analysis for the Physical Sciences. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical Methods. Ames, Iowa: The Iowa State University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehanna H, West CML, Nutting C, et al. Head and neck cancer - part 2: treatment and prognostic factors. Brit Med J. 2010;341:721–725. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cotrim AP, Sowers AL, Lodde BM, et al. Kinetics of Tempol for prevention of xerostomia following head and neck irradiation in a mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7564–7568. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spielberger R, Stiff P, Bensinger W, et al. Palifermin for oral mucositis after intensive therapy for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2590–2598. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buentzel J, Micke O, Adamietz IA, et al. Intravenous amifostine during chemoradiotherapy for head-and-neck cancer: a randomized placebo-controlled phase III study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:684–691. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn SM, Sullivan FJ, DeLuca AM, et al. Evaluation of tempol radioprotection in a murine tumor model. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:1211–1216. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00556-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metz JM, Smith D, Mick R, et al. A phase I study of topical Tempol for the prevention of alopecia induced by whole brain radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6411–6417. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vale JA, Meredith TJ, Goulding R. Treatment of acetaminophen poisoning. Ann Intern Med. 1981;141:394–396. doi: 10.1001/archinte.141.3.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Shown are three micrographs presenting the histological appearance of normal lingual epithelium (naïve), ulcerated lingual epithelium (IR only, with the brackets delineating the ulcer) and Tempol protected lingual epithelium (IR + Tempol, ip, intraperitoneal injection). The double-headed arrow indicates the area measured for epithelial thickness. The dorsal epithelial surface is shown.