Introduction

Health-seeking behavior, or seeking long-term, sustainable life-practices and communal activeness that will facilitate a healthy state can differ from person to person and culture to culture (Campinha-Bacote, 2003). This article will focus on the health seeking behaviors of two groups of northern plains Native American Indians (NAI) with persistent mental illness (PMI) living on two rural reservations, and will enhance health care providers’ understandings of their health care maintenance practices thus improving the provision of mental health care. Through these writings, the authors wish to honor the participants who shared their stories with us; we carry them in our hearts. AI/AN (American Indian/Alaskan Native) are used throughout this article when material relates to the larger community of indigenous people; when writing of the participants in this study, Native American Indian (NAI) is used. Also to support anonymity we will use the pronoun he only.

Background

Spector (2004) writes, “We learn from our own cultural and ethnic backgrounds how to be healthy, how to recognize illness, and how to be ill. Furthermore, the meanings we attach to the notions of health and illness are related to the basic, culture bound values by which we define a given experience and perception” (p. 5). We know how to seek health, how to describe or communicate health or illness, and how to ‘be healthy’ all within a relationship to cultural norms, values, and environments. Spector’s (2004) statement also touches on explanations for illness, be they interpreted as spiritual, physical, or psychological, which then drives our health-seeking behaviors. He continues that this is undergone by an AI/AN person through seeking a relationship to mainstream American culture, and to his traditional culture (values, beliefs, practices). This relational outcome can be integration (blend) of multiple cultural value systems. It is the challenge of an individual to define their health within one or more sets of cultural values. As Mehl-Madrona (1997), a Native American healer writes one of the first steps in treating a person is to listen to the story. Any HCP working with AI/AN needs to understand this because life experiences of health and illness of AI/ANs can be different from the mainstream medical model. Likewise, Campbell (1989) states, “culture is an important key in forging a positive health outcome” (p. 15).

Purpose

It is essential for the provision of culturally responsive care that mental health providers (MHP) know how rural NAIs experiencing PMI maintain their health. The purpose of this study was to discover health seeking practices utilized by Native American Indians (NAIs) with persistent mental illness (PMI) while allowing the emergence of a theoretical model. Secondary to this was the discovery of how utilization of these practices assists in their maintenance of wellness which benefits MHPs.

Methods

In order to engage different populations (minority groups) in the research process, researchers need different methods that are relevant to the population’s culture; equivalent to needing different approaches to health care delivery (Spector, 2004). Furthermore, standardized quantitative methods of measuring health seeking behaviors are problematic because of interpretations of influential cultural factors affecting testing (Blumer, 1969). In agreement with these authors, the decision to use grounded theory methodology, which fits with the oral tradition and story telling culture of NAI, and desire to discover a theoretical model, was made. The researchers also believe that multiple realities exist about health and health seeking behaviors within various patterns and Grounded Theory supports the emergence of similarities (themes) and differences. Grounded Theory according to Strauss and Corbin (1990), Chenitz and Swanson (1986), and Glasser (1992) was utilized in conducting data gathering (semi-structured interviews) and analysis (constant comparative), since the study focused on generating an understanding of social/psychological/behavioral phenomena or process.

Questions (semi-structured interview guide) used in this study have been effective during data collection in several other studies (Yurkovich, Buehler, & Symer, 1997; Yurkovich, & Symer, 2000). To determine cultural relevance, NAI mental health care providers reviewed questions and gave the researchers feedback on cultural relativity, before they accessed potential participants (Yurkovich & Lattergrass, 2008). Symbolic interactionism informs this study; interaction between clients and the research team created a dialogue focused on self-assessment/introspection by both parties.

Process

The research team obtained human subjects’ approval from the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the regional Indian Health Service’s (IHS) IRB before beginning data collection. Furthermore, IHS’s mandates of tribal resolutions and reporting of findings of the study back to relevant groups on each reservation were completed. The research team consisted of a veteran researcher (trained in, and had conducted and supervised 10 qualitative research projects), a NAI research assistant/cultural liaison and graduate research assistant.

Through the MHPs at two different IHS Human Service Centers on two rural reservations, eighteen NAI participants with PMI with five different tribal affiliations were recruited and participated in an interview. After obtaining informed consents for audio-taped interviews, members of the research team conducted the interview with each participant at sites convenient to the participants having intervals of 45 minutes to two and a half hours. The participants told their stories in their own words with limited interruptions by the researchers. The veteran researcher and a NAI research assistant conducted all interviews. Immersion in and analysis of the data continued for two more years with ongoing validation and enhanced input from NAIs and MHPs to insure cultural relativism (Yurkovich & Lattergrass, 2008).

Data Analysis

Constant comparative analysis began with coding and comparing for similarities and differences of the first two transcribed interviews, and progressed to establishing antecedents, context, conditions, strategies and consequences existing among categories of all the data. Memos were generated during interviews, while traveling to the next interview, and later in the hotel room discussion supported debriefing regarding shared stories. Microsoft Word was used for processing and storage of materials and team conferences for developing consensus occurred (Yurkovich & Lattergrass, 2008).

Requesting confirmation and clarification of interpretations by participants during interviews enhanced credibility and dependability. Also, sharing reports and models with health care providers (majority were NAIs) at the Human Service Centers validated that findings reflected the NAI culture. Finding concurrence through investigation of the literature and documents completed data triangulation (Streubert, Speziale & Carpenter, 2003). Moreover, repetition/saturation of data was present within and across tribes.

Description of Sample

The purposive sample consisted of 18 adult NAI clients having five different tribal affiliations. Eleven were males, with seven being females. Ages ranged from 21 to 54 with the mean age being 36 years old. There were six different DSM IV-TR diagnoses represented. The years that participants had a diagnosis ranged from 7 to 25 with an average of 13 years (Yurkovich & Lattergrass, 2008). Diagnoses given the participants included depression, bipolar, post-traumatic stress response/disorder, anxiety/panic, schizophrenia, and chemical dependency. However, given the debate that the DSM-IV TR is not always a fit with this culture (O’Nell, 1996; Norton, De Coteau, Hope, & Anderson, 2004; Csordas, Storck & Strauss, 2008), the researchers perceived their identified symptoms as being a better reflection of their mental illness. The most common symptoms identified were anger, sadness/grief and anxiety regardless of their diagnosis, which could be connected to their shared traumatic stories of victimization (physical and/or sexually); experiencing betrayal, abandonment, or loss of significant others; and witnessing or engaging in violence. Differences did not exist between genders; similarity was present in stories told by both genders.

Within the research sample, participants identified themselves as, 1) non-traditionalist, or mere “observers” of their culture, 2) traditionalists who knew and practiced cultural traditions but did not always speak the language; and 3) blended which is being bi-cultural or culturally integrated. Participant variation, present in the age range, gender, diagnoses, and tribal representation, adds rigor to the study’s results.

Findings

Definitions

To provide a culturally relevant framework/context the authors are also stating the composite definition of health that emerged from these participants in this study to enhance the understanding of these findings. The following definition represents key themes that emerged from this population of participants. Health was defined by NAIs with PMI as:

Having a balance or a sense of harmony, equilibrium, not out of control of their person, this includes the spiritual, cognitive, emotional, social, and physical domains. Health does not mean being without an illness, rather it means being empowered through knowledge of illness, and/or honest self-awareness. Equilibrium/harmony consists of maintaining a sense of control over their well being and symptoms while having hope and a purpose for managing their illness while using the formal mental health care system … and informal network … as support resources (Yurkovich & Lattergrass, 2008, pg. 448).

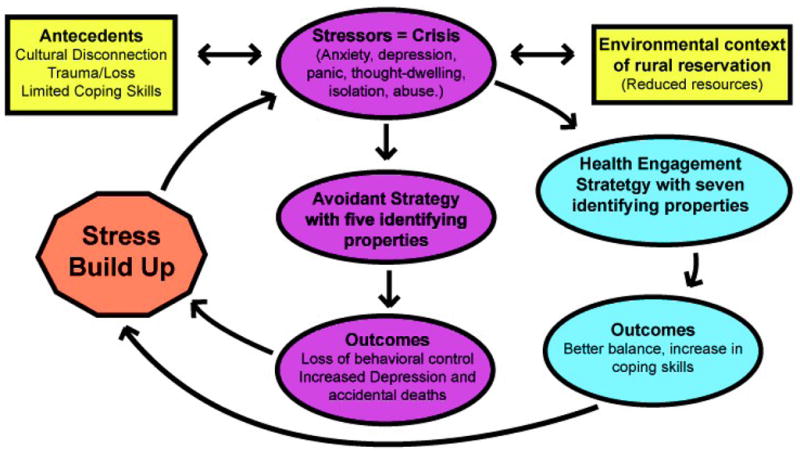

For the purpose of this article, the authors define health seeking behaviors as conscious actions whose function is sustainable “well being.” This incorporates awareness of and mutual participation in life practices and communal activities that support a healthy state. Within this context of understanding, two major approaches emerged that NAIs with PMI use as health seeking behaviors, 1) health engagement, and 2) avoidant strategies. Figure 1 depicts the two major health seeking behaviors and the practices that are enacted to actualize the behaviors. It also speaks to the dynamic nature of stress and how it can impact the choice of a health seeking behavior. Although this article is more focused on health engagement activities (due to length) it is important to recognize avoidant strategies, since they are the fall back plan for individuals who are quickly overwhelmed and cannot because of a variety of barriers enact health engagement strategies.

Figure 1.

Processes of Seeking Mental Health by Native American Indians with PMI

Health Engagement Strategy

Health engagement strategy used for the establishment of mental wellness and its maintenance has seven practices and is the central focus of this article (see Figure 1). The second strategy, avoidant behaviors, are present as part of the model; its complexity can not be completely addressed in this article. Suffice it to state, avoidant behaviors were seen as the person’s best coping strategy for the emotional level being experienced and the immediate context of the problem; most often there had been a “piling up of unresolved problems.” The fifth practice of avoidant behaviors -- leaving the reservation was a positive necessity that supported soberness and non-engagement in chemical recreational use/abuse (see table 1).

Table 1.

Strategies with Properties to Establish and Maintain Mental Health of NAI with PMI

| Strategies | 1.Health Engagement | 2. Avoidant Behaviors |

| Properties | PracticeSpiritual Activities | Chemical use and abuse |

| Talk with Someone | Doingsuicidal behaviors | |

| Meaningful Doing or Purpose | Non-engagement in therapy | |

| Use Medication | Denial of symptoms and treatment needs | |

| Use Solitude | Move off or leave the reservation | |

| Learn about Ones Illness | ||

| Perform Healthy Physical Behaviors |

Practice of Spiritual Activities

The first practice of the health engagement strategy is spiritual activities, which included ceremonies related to Native American Indian traditions (sweats, smudging, and Sundance most frequently mentioned without any indication of using psychoactive substances) and practices from other religious denominations (bible reading, talking to God/praying, attending church services, meditating, having faith, and talking with priest for counseling). The Native ways, Catholic practices, bible focused churches (Christians) and a blend of beliefs (Christians and NAI spirituality) were the most common affiliations mentioned. Spiritual practices supported their wellness/balanced state by enhancing their self perceptions and introspection; “We need to think about [meditate] how we’re living our lives and if we need to make changes.” Even the participants, that did not engage in spiritual practices and believes, spoke to their awareness of it being necessary for wellness/wholeness, “I probably should get into the tradition of religion. I’d probably feel better about myself or I think that’s the part that makes you complete.”

Other participants stated, “What I have to do to complete my circle is start having faith in something. Really! And I’ve known that for some time… so I’m not going to be healthy until I do,” and

I really wanted to drink… and I just started crying and stuff and I said, ‘you know, I don’t want to drink.’… And so I started praying and I had my [medicine] bag that I brought along… there was some sage in there. So I took that…I smudged up… and I started praying.

The participants that spoke strongly about their practices also shared that they grew up in a family which had grandmothers with strong beliefs and practices including a blend of beliefs. These activities were commonly identified as; attending church, praying and being “into family.” Participants recognized spiritual practices as a way to deal with depression, loss, staying sober, and coping with stressors and illness symptoms; spiritual behaviors were seen as central to their definition of health and maintenance of their balance (Yurkovich & Lattergrass, 2008).

Practice of Talk with Someone

“Talk with someone,” included the use of the formal (therapist, social worker, psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse, or community health representative in individual or group processes) and informal health care systems (family, elders, priests/ministers, friends, and peers). ‘Talking’ as a maintenance strategy gained understanding about their illness, and provided socialization that reduced isolation, which participants recognized as leading to depressive thoughts; if not checked this led to suicidal behaviors. In consideration of the latter point, a participant stated, “I used to think [that going] to my room, and sitting in there …turning the music on. That [it] was good for me… it put me further down into being depressed and now I go out [and] I talk to somebody.” One participant stated, “If I’m feeling that way I’ll call up [a therapist] or somebody down here [at the human service center] and say I don’t feel very good anymore. But this is usually when I’m alone. Trying to fight, you know, stay away from alcohol.” Another participant spoke to controlling symptoms while in crisis:

I think of things [remembers trauma] and that is about the only time I can open up to people is when I’m that far gone. When [this happens] I have to go talk to someone or I feel like I’m going to just lose control, you know? You have to find someone immediately and talk because you can’t just go to anybody. They [family members] don’t understand. I eliminate them. I feel when I get to that point I need to see a professional person because I can pretend to anybody else; you can’t fool a professional most of the time.

This person was able to recognize that when he is in a critical/crisis state it is not the time to talk with the informal health system. However, for some a peer would work if “he understands what I go through.” Participants also identified group therapy as being helpful in talking about their problems since they do not have to spend a great deal of time explaining their mental illness; these group members easily understand, listen, and are supportive. Talk therapy is a valued health engagement strategy.

However, participants indicated it took a great deal of courage to talk to someone in the formal health care system because talk therapy is not part of their “independent, self sufficient, stoic” culture, which directs them to “take care of themselves” and not seek assistance. Courage was needed to change their behaviors and go in opposition to the collective cultural perception. A participant stated, “There’s a lot of shame… I was so scared to even come here [human service center]. I didn’t even know this place existed when I came in here. I didn’t know what’s going on with me…I wasn’t feeling very good.”

Additionally, the informal health care system offers further assistance through the provision of support, distraction from their symptoms, socialization, and the giving of advice; ultimately creating a better balance and a reduction in their emotional pain. Participants spoke of their, “balance getting shifted and you’re getting depressed and you start to isolate,” and at this time they start talking to friends, grandmothers, mothers, “aunties,” and elders that they know “have knowledge of what they are dealing with.” A participant stated, “I talk a lot. And I talk to a lot of elders… because they’ve lived longer, they know more, they’ve been through it. I feel a lot more guided by them than by my peers who are struggling like I am.” While another participant stated the following about his use of an informal health network, “I talk to my friend out here, [where I live] and I’ve got a friend who is sober. He comes and drinks coffee with me in the mornings.”

Discrimination of who to talk with and at what times is significant to effective use of the informal health system. Usually talk therapy was beneficial with the informal health system at a more superficial level since it provided the socialization and distracting activities needed to reduce isolation and symptoms, but not helpful for in-depth discussions of their illness. One participant made this astute summative statement about talk therapy, “I probably wouldn’t be here if I hadn’t gone [to therapy/treatment]. When I did, I felt so much better about myself … I wish more people knew how much better it makes them feel, because it’s just as harmful to let that [mental] go as anything else on your body.” When talking wasn’t available (e.g. people too busy, or could not be reached, etc.) other health engagement or avoidant strategies were employed.

One other universally acknowledged difficulty, related to talking with the informal system members was finding a place to do it; one that they saw as beneficial, supporting wellness and “safe” to their own wellness state (e.g. no alcohol in the environment). They spoke of needing a place to gather with peers for mutual support such as a “clubhouse.”

Practice of Meaningful Doing or Purpose

Purpose for their existence was significantly intertwined with meaningful doing. These behaviors gave them goals to work towards, enhanced their “pride” and “feeling good about self,” “reduced boredom” and helped them control symptoms. Meaningful doing supported their ability to be altruistic, feel normal by having some independence through generated “spending money,” and filled a “gap of nothingness.” A participant showed a great deal of pride while speaking of his work in a thrift shop which gave him the opportunity to make ‘some money’ that supported a trip, “to town and eat pizza and go to the museum.” This meaningful doing also consisted of caring for sick relatives or grandchildren, sharing talents or self with others, giving away to others personally created products from their hobbies (e.g. bead work, quilt making), having a job; as one participant stated, “I’m there for my kids and my grand kids and I feel like I’m still useful. They always need you.” Another person spoke of helping others in this way: “Sometimes it is [a burden to be the ‘core’ of the family] but then I know that I have a lot to offer my family - my brothers and my sisters…I always say I have to do…one good deed a day [to stay healthy].”

Participants also spoke of the negative effects of being without something to do and how doing can help in controlling unhealthy behaviors,

“You … can’t find anything to do then you get bored… boredom leads to anxiety… that’s something to stay away from. You know, you don’t want to get anxiety or depression. You need something to do… [like] play guitar, read books, work on art hangings, whatever. That’s what I do.”

Another person spoke to how doing motivates one to stay away from unhealthy behaviors, “I have an elderly mother that I need to take care of, so I’ve left that scene [of using alcohol] and I’ve moved back in with my mother and I’m taking care of her. She keeps me sober.” Goals of going to college to be able to give to others or getting a job were voiced by several. With the very high unemployment rate on reservations, accessing work was very difficult.

Practices of Use Medication

The fourth practice of health engagement, use/take medications, had mixed reviews by the participants. There was clearly a continuum of experiences related to taking medications as the following quotes show: 1) “I take my medication. If I don’t take my medication, I’m sick. I’m ruined for the day. My medication keeps me going.” 2) “You know I wasn’t a believer in medication. I thought they were just going to make me worse, they work some of the time.” 3) “Those voices….they used to drive me crazy. They (mental health providers) always had me come back and get my medicine. [The medicine controls the voices] most of the time,” (identified presence of some non-adherence), 4) “Being on meds I suppose [helped me stay healthy]. I thought they were just going to make me worse…I’m planning on weaning myself off of them and stay okay,” and 5) “Medications aren’t really helping.”

The latter quote (#5) speaks of the difficulty of finding the right medication or having been switched to other medications, since they were not working anymore. Most identified that they took them because they knew they were necessary to manage their illness and they could speak to the consequences when they do not use them (e.g. an increase in depression, anxiety, voices, and racing thoughts). Unfortunately, psychiatric visits for medication management happened about once every three to four months unless the person was in a crisis state. Moreover, the visits were brief and focused on medication supervision; little time for talk therapy (confirmed by participants and providers) which limits the effectiveness of medication.

Practice of Use Solitude

Solitude is different from isolation and is perceived as benefiting their ability to deal with stressful “chaos,” and creates a healing environment to reduce/control symptoms. One participant identified the benefit of solitude as, “I don’t get in anybody’s business and they don’t get in my business and everything seems okay;” thus, there is no distress. Also, solitude was seen as, “Quiet mornings, not a lot of people telling me ‘you should be doing this here and you should be doing that;’ a time of peacefulness.” Another person presented solitude as, “getting away from people and being by yourself…alone.” Within this ‘alone time’ different activities may happen. Some examples are, “lose myself in my crafts,” “I go out and I walk,” “I pray, think, meditate,” “journaling…to put my feelings out of myself…down on paper” and “I do self-talk… the kind [where] you have to tell your mind to get into the present, or try to deal with some of those [negative] thoughts… Turn them off [thought stopping].” Self-talk within solitude was discussed further by stating that he used the time to reframe his thinking-as in “cognitive behavioral thinking.”

Many participants realized that solitude could move into isolation which was not to their benefit as these participants indicated, “There is a point when I’m alone for too long that it’s not good or things are not getting better,” and “It [solitude] could be bad whenever you need to be around people and talk.” In these cases awareness of this change is essential. When awareness is not present they reported that family members would call and inform them that they have not heard from them for several days. As a participant indicated, “Sometimes I don’t even know that I’m doing it [isolating]. Unless my mom or somebody starts telling me that I am.” Whereas solitude can be of value in wellness maintenance, it may take concerned others (their informal support community) to help them avoid the unhealthy direction of isolation.

Practice of Learn about Ones Illness

Participants, that had been in treatment programs that focused on teaching them about their disease and how to manage it, spoke to feeling empowered by this knowledge, had more “confidence in themselves,” and were “feeling better” about themselves and their ability to stay in balance. Learning that their mental disability did not mean they were “crazy,” but rather that they had a disease (not all that different from their relatives who had diabetes or heart disease), and needed to take medication everyday, made a significant difference to these participants.

One participant spoke of many aspects related to her illness that needed new learning/knowledge,

When I started my journey, there were still issues that I had to address so I got involved with a support group of adult children of alcoholics, and then kind of relearning how to trust again. Trying to convince myself that one of the biggest character defects was jealousy, but most importantly I had to learn how to be intimate and in the intimacies, to not be jumping in the sack, but being able to be there.

So learning through new knowledge and awareness included changing behavior for their wellness maintenance. Knowledge also helped some participants recognize when there was a need to get assistance and not continue in a state of psychic pain. It was apparent during the interviews and feedback requested that some participants did not have adequate knowledge about their PMI and/or how to effectively deal with or treat it (e.g. use talk therapy only in a crisis).

Practice of Perform Healthy Physical Behaviors

The performance of healthy physical behaviors was recognized as significant to maintaining their wellness because they knew of the connection between their physical state of being and their ability to stay mentally/emotionally in “balance;” a wholeness of person was essential to wellness. Healthy physical behaviors that were consistently presented during the interviews were “eating well,” exercise, and adequate sleep. Comments about eating included, “I just try to eat right,” “three meals a day and I try to make healthy meals not just some junk food,” “eating healthy where, you know, your sugar’s not too high,” and “careful about my weight.” The last two quotes allude to participants’ concerns about diabetes; either they or family members had this disease. They were motivated to prevent diabetes and heart disease.

Exercise was practiced in several different ways; the most common being walking, running, playing a sport, or “staying in shape for a sport”. Walking was identified with several benefits as present in these quotes; “my mind isn’t thinking about negative stuff,” “I like to go out in the woods and just walk and I like nature. That helps me stay closer to myself,” and “I am not depressed… after my work outs.

Adequate sleep was desirous by all participants. Many participants used how they felt when they awoke in the morning as a way to determine if they were going to feel healthy that day. Some participants, that had a job and worked shifts, spoke of sleep interference, “I try to get more sleep, trying to get into a rhythm.” Participants indicated their lack of sleep negatively impacts their mental illness, and supports a depressive process along with inertia.

Avoidant Behavioral Strategy

The second health seeking strategy emerged as avoidant behaviors. There are five practices that explicate the meaning of this strategy (see table 1) which will be given cursory attention due to there complexity. Avoidant behaviors were seen as the person’s best coping strategy/response for the emotional level being experienced and the immediate context of the problem which may have barriers to choosing healthier behaviors.

The practice of chemical use and abuse was often discussed within the context of “self-medicating;” a process of “numbing” self to undesirable feelings and thoughts; and temporarily eliminating memories of trauma, betrayal, losses (recent and distant), or abuse. This behavior in the beginning also reduced depression but with continual use created a backlash of more depression. Using this strategy blocked their ability to choose healthier practices and engage in treatment for their PMI. They would reengage in healthier practices when the stress or crisis was reduced and better decisions or coping choices were possible. For some it meant they had to reach the point of recognizing they were “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

The second practice of the avoidant strategies, suicidal behaviors related to a sense of hopelessness, and existed in the environmental context of poverty, high rates of unemployment, and intergenerational depression. The latter point was recognized most often by participants that had lived off the reservation and could thus compare this experience to the reservation atmosphere, and by MHPs.

The third practice is non-engagement in therapy. Some NAI participants spoke of not engaging in talk therapy for a lengthy time period, which was influenced by their culture, stigma, and not knowing/understanding its full purpose/benefits. Once their crisis or psychic pain was under control there was no need to continue with therapy until the next crisis or an overwhelming stressful event occurred; this became equivalent to only three or four interventions with human service providers (confirmed by providers).

The fourth avoidant practice, denial of symptoms and treatment needs, has similar origins as the third one; denial supports the cultural beliefs of being strong, independent, and “fixing it themselves.” Some participants began this process of fixing it through use and abuse of chemicals. There were also confounding factors of not knowing what was wrong, how to deal with it, and who to seek for assistance. As a participant indicated, “I did not know that the human service center existed or what it was for.”

The fifth practice of avoidant behaviors is leaving the reservation. Participants that discussed this as an option did so in a positive way since they perceived their departure as supporting sobriety. These tribal members had also found meaningful doing outside the reservation without chemical use/abuse. However, they returned for various significant family reasons. Therefore, leaving the reservation was useful to their maintenance of wellness, whereas the other four strategies were temporarily beneficial or very detrimental to balance.

Process of Seeking Health Resources

In the analysis of data shared by participants, it became apparent that many factors affected seeking health care resources, choosing avoidant behaviors, and stress build up. First there had to be recognition that there was a problem; meaning awareness that the way they were feeling (experiencing psychic pain) was not normal or not “like other family members.” Unfortunately, sharing this information with family members did not always get a helpful response and at times created the stigma of being seen as “crazy,” which was difficult to deal with since this has multiple meanings in their culture (Grandbois & Yurkovich, 2003). Some spoke of being motivated to seek assistance when they could “not take how bad they were feeling anymore,” felt they were “losing control,” or “had a very bad scary experience” of a physical type (seizure or blackout). Extreme pain (crisis) created awareness and motivation to act.

Furthermore, lack of knowledge about their illness and uncertainty regarding which approaches and when to use them to cope with their memories, abuse, and psychic pain negatively influenced their ability to maintain wellness. It was clear that at a high level of pain/distress (piling up of unresolved stressors), accessing professionals (not peers and family members) or use of avoidance strategies were the directions to go. Avoidance strategies were also employed when the participants’ attempts to get help was thwarted (e.g. “could not reach human service provider”) and when they lost control of their feelings and did not recognize other healthier options (overwhelmed with a high level of anxiety and loss of cognitive processing).

Discussion and Implications

The health engagement strategy with its seven properties assisted NAI participants with PMI in maintaining a “balance.” However, what was apparent was the presence of ambiguity in determining when to use them and a lack of self-awareness of their escalating distress which placed them at greater risk for using the less effective/detrimental avoidance strategies. During the treatment process education about what treatment consists of and which coping strategies resolve beginning stressors, could reduce the pile up of anxiety and depression; thus supporting ones choice of the healthier strategies.

Being independent or self-sufficient (self-mastery), which was their perceived expectation within their culture, was hindered by the emotional effects of intergenerational depression, trauma, loss, and environmental contexts that support cultural disconnects. Furthermore, there was limited understanding in how to effectively use their ‘communal connections’ to maintain wellness and reduce barriers to communal mastery (stigma, limited support system) which could heighten their coping processes (Hobfoll, Jackson, Hobfoll, Pierce, &Young, 2002). The communal mastery would also support the culturally based importance of family relations. Many participants also spoke of their need and the family’s need to gain a greater understanding of mental illness and ways to manage it, so together they could issue control over behaviors and feelings; establishing harmony in their lives.

The two major health strategies, unless viewed within a historical or cultural context, may seem very dichotomous. The second strategy of avoidance with its’ five practices, can be difficult to comprehend, or could be viewed as a reactionary response. However, all of the participants admitted to engaging in some form of both strategies in the recent and/or distant past for an alleviation of symptoms. Their reported quick escalation of distress and its contextual nature with barriers influenced the decision-making process of choosing the avoidant strategy. A deficit in knowledge, and feeling limited community support were also influential factors in this process.

Without justifying the individual choice of these avoidance strategies (as in any society it is the individual who determines the use of these strategies), MHPs and the NAI community must ask, “Can these strategies be assessed and interrupted in a way that leads towards compassionate and socially responsible action on the part of a wider swath of their society?” Rather than continuing to perpetuate miscomprehension, and enhance alienation, the literature supports the possibility that such avoidance choices are often made according to a set of environmental elements; an intergenerational learned element validated through participants’ discussions on how other family members coped. Strickland, Walsh, & Cooper (2006) reported that AI/AN parents and elders perceived the major task to reduce suicide (one of the avoidance behaviors) was holding the family together and healing intergenerational pains, which included holding onto cultural values, and getting an education and a job (meaningful purposeful doing). They supported the need for community based interventions. Jiwa, Kelly, Pierre-Hansen (2008) indicate that successful solutions require, 1) development of treatment programs within communities, 2) strong interest and engagement by community members, 3) demonstration of leadership skills, and 4) sustainable funding. Additionally, literature speaks to the need for community capacity building and community empowerment as strategies for reducing health disparity and enhancing public health (Chino & Debruyn, 2006).

Literature, aimed at cross-cultural understanding, views mental illness as a potential symptom, that can not be altered without the commitment of the individual and the collective power of a community dedicated to change. Table 2 addresses the present services provided on the reservations, the “wishes” held by human service providers on the reservations (Grandbois & Yurkovich, 2003) and the identified needs of the NAI consumer. It is apparent from this table that IHS provides for a person in need of medication supervision and acute interventions. Even with the availability of extending counseling services beyond a crisis, participants do not tend to consistently engage in this therapeutic process. The health care providers are more closely aligned with the identified needs of their clients. They see the need for a therapeutic environment that supports community dwellings, socialization, purposeful doing, and normalization of their lifestyles by prevention of acute episodes and support of wellness states. The tribal community of providers, consumers and members need to engage in change processes, and consider program development that brings current services more closely in alignment with the verbalized reality of rural reservation life including the defining and integrating of underlying cultural frameworks.

Table 2.

Listing of Human Services Available and Desired for NAIs with PMI

| Current Human Services | Reservation Health Care Providers’ Wishes | NAI Consumers’ Perception of Useful Services |

|---|---|---|

Outpatient services

AcuteHospital care

Long term mental health care provided in state facility (off the reservation and only when funding resources are available) |

OutpatientCenter that provides resources and services frequently accessed in one location. Day treatment programs for peer support and meaningful doing activity. Integration of cultural practices ceremonies into treatment Safe housing resources with supportive living Work programs with peer support Safe heaven for peer socialization (club) Support groups for teaching/education about health concerns/issues Respite services for family members Toll free telephone numbers for consumers to access MHPs. Production of PSAs for radio broadcasting of information and education on mental health and mental illness Presence of Advanced Practice Mental Health Nurses |

Talk therapy (individual or group as in talking circles and support groups) Toll free phone numbers for immediate access to MHP beyond reservation boundaries (e.g. VA resources) Education about their illness and its management for personal empowerment Administering/prescribing/supervising of medications that are their needs Safe and secure environment to live in, socialize in, and enact meaningful doing to support a sense of purpose (e.g. residential setting, community center, or psych social club) Opportunities for meaningful doing (e.g. sheltered work settings, low stress jobs, opportunity to volunteer) which provides experiences in doing for others. Residential treatment for chemical addictions that is culturally based in Native traditions and non-confrontational. |

Conclusion

Authors have attempted to compare cultural values of AI/AN and mainstream American values resulting from different historical experiences and conflicting social and spiritual practices (Aragon, 2006). This discussion of health seeking strategies and behaviors of the NAI with PMI attempts to enhance cultural understanding by gathering and sharing their perceptions; thus giving health care providers and communities the information needed to ensure culturally relevant and responsive compassionate mental health services and care.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by an Otto Bremer Foundation Grant and UND College of Nursing Office of Research grant and by Grant Number C06RR022088 from the National Center for Research Resources. We humbly thank all the American Indian participants for graciously accepting us into their community and honoring us by sharing their wealth of information through the stories they entrusted to us. We also wish to recognize the contributions of our research assistant Sara Roy, BSN (Chippewa).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Eleanor E. Yurkovich, Email: eleanor.yurkovich@email.und.edu, Professor Emerita, University of North Dakota, 430 Oxford St. Stop 9025, Grand Forks, N.D.58203, Phone: 701 777 4554.

Izetta Hopkins (Lattergrass), Email: izahopkins91@hotmail.com, Language Apprentice Coordinator for Tribes Boys and Girls Club, Three Affiliated Tribes, PO Box 1084, New Town, ND 58763.

Stuart Rieke, Email: stuartrieke2@gmail.com, Instructor, Sisseton-WahpetonTribalCollege, Sisseton, SD, Phone: 605 698 3966 ext. 1202.

References

- Aragon MA. A clinical understanding of urban American Indians. In: Witko TM, editor. Mental health care for urban Indians. Washighton, DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer H. Symbolic Interactionism; Perspective and method. London: Prentice –Hall; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell GR. The changing dimension of Native American health: A critical understanding of contemporary Native American health issues. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 1989;13(3/4):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. The Process of Cultural Competence in the Delivery of Healthcare Services: A Culturally Competent Model of Care. Cincinnati, OH: Transcultural C.A.R. E. Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Chenitz WC, Swanson JM. From Practice to Grounded Theory. Menlo Park, CA: Addison Wesley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Chino M, Debruyn L. Building true capacity: Indigenous models for indigenous communities. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):596–599. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas TJ, Strock MJ, Strauss M. Diagnosis and distress in Navajo. Journal of Nervous Mental Disorders. 2008;196(10):725–726. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181812c68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser BG. Emergence vs. forcing: Basics of grounded theory analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Grandbois D, XXX Policy issues restricting American Indian rural mental health services. Rural Mental Health. 2003 Winter;28(1):20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE, Jackson A, Hobfoll I, Pierce CA, Young S. The impact of communal-mastery versus self-mastery on emotional outcomes during stressful conditions: A prospective study of Native American women. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(6):853–871. doi: 10.1023/A:1020209220214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiwa A, Kelly L, Pierre-Hansen N. Healing the community to heal the individual: Literature review of aboriginal community-based alcohol and substance abuse programs. Canadian Family Physician. 2008;54(7):961–963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehl Madrona L. Coyote medicine: Lessons from Native American healing. New York: Simon and Schuster; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, De Coteau TJ, Hope DA, Anderson J. The factor structure of the Anxiety Sensitivity Index among Northern Plains Native Americnas. Behavioral Research Theory. 2004;42(20):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Nell T. Disciplined Hearts: History, identity, and depression in an American Indian community. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spector RE. Cultural Diversity in Health and Illness. 6. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Strickland CJ, Walsh E, Cooper M. Healing fractured families: Parents’ and elders’ perspectives on the impact of colonization and youth suicide prevention in a Pacific Northwest American Indian tribe. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2006;17(1):5–12. doi: 10.1177/1043659605281982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Streubert Speziale HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. 3. New York: Lippincott; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yurkovich EE, Buehler J, Symer T. Loss of control and the chronic mentally ill in a rural day-treatment center. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 1997 July–Sept;33(3):33–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.1997.tb00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yurkovich EE, Lattergrass I. Defining health and unhealthiness: Perceptions held by Native American Indians with persistent mental illness. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2008 July;11(5):437–459. [Google Scholar]

- Yurkovich EE, Symer T. Health maintenance behaviors of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals in a State Prison. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services. 2000;18(6):20–31. doi: 10.3928/0279-3695-20000601-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]