Abstract

A combination of a chiral N-heterocyclic carbene catalyst and α,β-unsaturated aldehyde leads to a catalytically generated α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium, which participates in a highly enantioselective annulation to give dihydropyranone products. This full account of our investigations into the scope and mechanism of this reaction reveals the critical role of both the type and substitution pattern of the chiral triazolium precatalyst in inducing and controlling the stereochemistry. In an effort to explain why stable enols such as naphthol, kojic acid, and dicarbonyl are uniquely efficient, we have postulated that this annulation occurs via a Coates-Claisen rearrangement that invokes the formation of a hemiacetal prior to a sigmatropic rearrangement. Detailed kinetic investigations of the catalytic annulation are consistent with this mechanistic postulate.

Keywords: N-heterocyclic carbene, Claisen rearrangement, redox reaction, acyl azolium, organocatalysis

INTRODUCTION

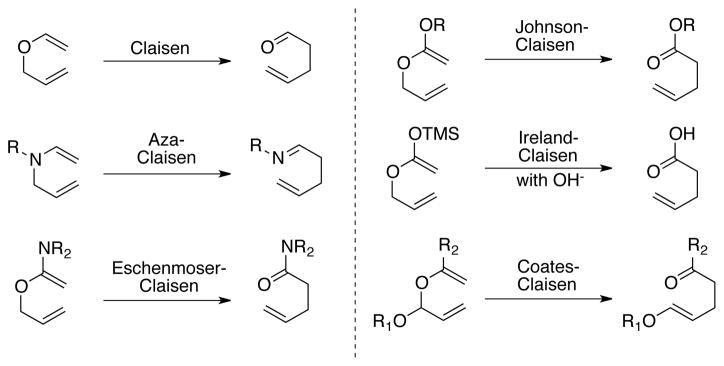

Since its discovery in 19121 the Claisen rearrangement has been celebrated as one of the most powerful methodologies in organic chemistry. The sheer number of the existing variants of the Claisen rearrangement2 emphasizes the captivation and utility of this carbon–carbon bond forming reaction (Scheme 1). While many other highly valued C–C bond forming reactions, including aldol reactions, cycloadditions, conjugate additions, and benzoin/Stetter-type reactions, have progressed from racemic and diastereoselective variants to catalytic, enantioselective processes, progress in the development of catalytic asymmetric variants of the Claisen rearrangement has been slower. The use of chiral Lewis acid complexes to evoke reagent-controlled asymmetric Claisen reactions is well established,3,4,5 but product inhibition typically requires the use of superstoichiometric quantities of the chiral reagents. Efforts to overcome these limitations by substrate design and the development of new catalysts have led to some enantioselective variants and the identification of formal Claisen rearrangements using metal catalysts such as Cu6,7, Mg8, Pd9,10,11, Au12, Ir13,14 and Ru.15 The well-studied biological rearrangement of chorismate to prephenate promoted by the enzyme chorismate mutaste16 has long inspired organocatalytic approaches17,18 to the Claisen rearrangement. Pioneering work by Curran19 on urea-promoted Claisen rearrangement of allyl vinyl ethers has been recently developed by Hiersemann20 and Kozlowski21 and further elaborated into a highly enantioselective processes by Jacobsen.22, 23, 24 These impressive achievements still leave room for new approaches to catalytic, enantioselective Claisen-type reactions that improve reaction times, substrate scope, and selectivity.

Scheme 1.

Selected variant of Claisen rearrangement

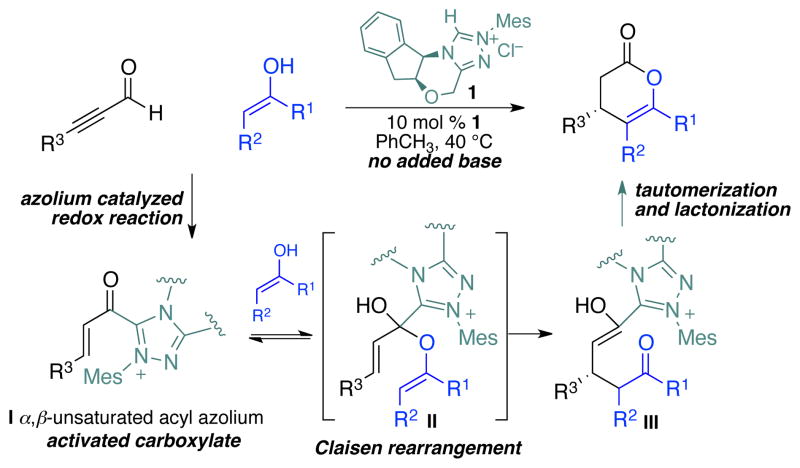

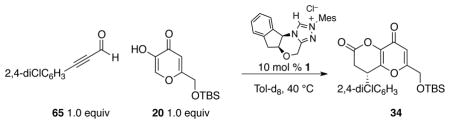

In the course of developing enantioselective, NHC-catalyzed reactions of catalytically generated reactive species25, 26, 27 we identified an intriguing annulation reaction of ynals and stable enols. Key to this approach is the catalytic generation of the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium (I, Scheme 2) by an internal redox reaction of ynals. This new NHC-promoted transformation proved amenable to enantioselective catalysis with chiral triazolium salts to afford enantioenriched dihydropyranone products in excellent yield. Contemporaneously, Lupton has reported the related NHC-catalyzed annulation of α,β-unsaturated acyl fluorides and enol silanes28 or unsaturated enol ester29 using achiral imidazolium-derived NHCs – a process also thought to occur via a related unsaturated acyl azolium. Xiao,30, 31 Studer,32, 33 You,34 and Ye35 also reported similar annulation cascades. Lupton36 has recently reported an elegant NHC-catalyzed formal [4+2] cycloaddition that proceeds via the catalytic generation of α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium. This unique C–C bond forming activation mode represents the fifth discrete reactive species that can be generated from the combination of α,β-unsaturated aldehyde and an N-heterocyclic carbene. The other four (acyl anion equivalent,37, 38 homoenolate equivalent,39, 40 ester enolate equivalent,41, 42 and acyl azolium43, 44) already have a rich chemistry of highly enantioselective C–C, C–O, and C–N bond forming processes. An improved understanding of the mechanism and scope of reactions proceeding by the α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums is critical to the further development of this field. In addition to their synthetic utility, α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium has also been invoked as an intermediate in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites.45

Scheme 2.

An NHC-catalyzed Claisen rearrangement

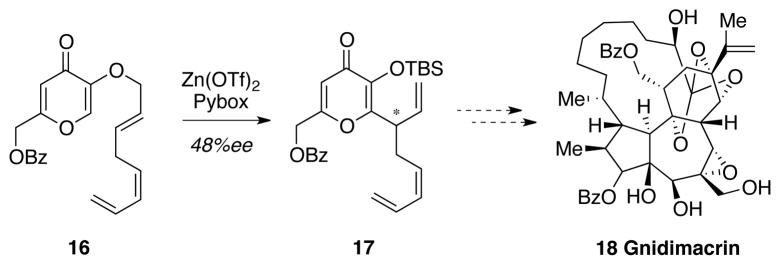

In our initial studies we applied this finding to a catalytic, enantioselective Coates-Claisen reaction46, 47 of kojic acid-derivatives to give enantioenriched products that have been proved to be both synthetically useful48 and difficult to prepare otherwise.49, 50 We have also conducted extensive investigations into the reaction mechanism and confirmed that the reaction occurs via a Claisen-type rearrangement in our cases51, 52 rather than a 1,4-addition of the enol to the catalytically generated α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium.53, 54 Furthermore, our elucidated mechanism suggested that the Claisen rearrangement on the hemiacetal intermediate (II) should be the stereochemically determining step. These efforts, however, did not address the question of whether or not the NHC-catalyst was lowering the activation barrier for rearrangement or simply acting to preorganize the substrates. In this report we document our investigation of various catalyst types and the substrate scope expansion of this reaction, as well as our full investigations into the nature of this new class of NHC-promoted carbon–carbon bond formation.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The possibility of affecting an NHC-catalyzed Claisen-type rearrangement emerged from our interest in NHC-catalyzed acylation reactions of alcohols55 and amines.56, 57, 58 Our own efforts, as well as prior works from Breslow,59 Daigo,60 White and Ingraham,61 Bruice,62 Lienhard,63 and Owen64, 65 have found that acyl azolium species are excellent acylating reagents for alcohol66 and water but react only slowly with amine.67 Daigo and Owen attributed this unusual behavior to the rapid formation of kinetically important hemiacetals in the acylation reaction, suggesting that intermediate II would have a significant lifetime during the acylation of enol.68 Furthermore, our prior work on NHC-catalyzed annulations have evoked an NHC-mediated oxy-Cope rearrangement69 as a possible pathway for C–C bond forming reactions.

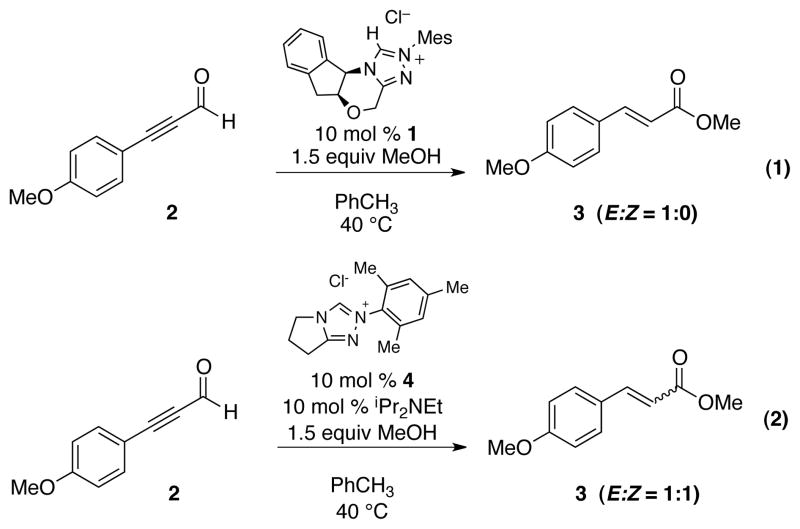

In order to generate the key α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium species, we adopted the clean and rapid redox esterification of ynals originally reported by Zeitler.70 This reaction was thought to proceed via the catalytic generation of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums – a postulate that we have recently confirmed by characterization of this key intermediate.71 In consistent with Zeitler, sterically hindered azolium catalysts such as IMesCl or 1 stereoselectively generated E ester 3 as the exclusive isomer deriving from an (E)-α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium species. Less sterically demanding catalyst such as 4 gave a mixture of E and Z isomers (Scheme 3). This stereoselective generation of the key α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium intermediate should simplify the possible transition structures available during the Claisen rearrangement, conceivably leading to a high level of enantioinduction.

Scheme 3.

Stereoselective generation of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums

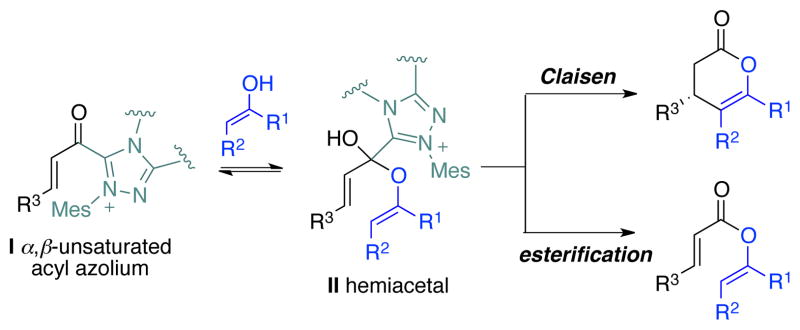

We anticipated that the correct combination of substrates and catalysts could lead to an annulation reaction via the Coates-Claisen pathway (Scheme 4). The competing reaction would be the simple esterification; it was also conceivable that the resulting vinyl esters of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes could serve as a substrates, as these are known to be attacked by NHCs under the appropriate condition.

Scheme 4.

Competing pathways of hemiacetal intermediate

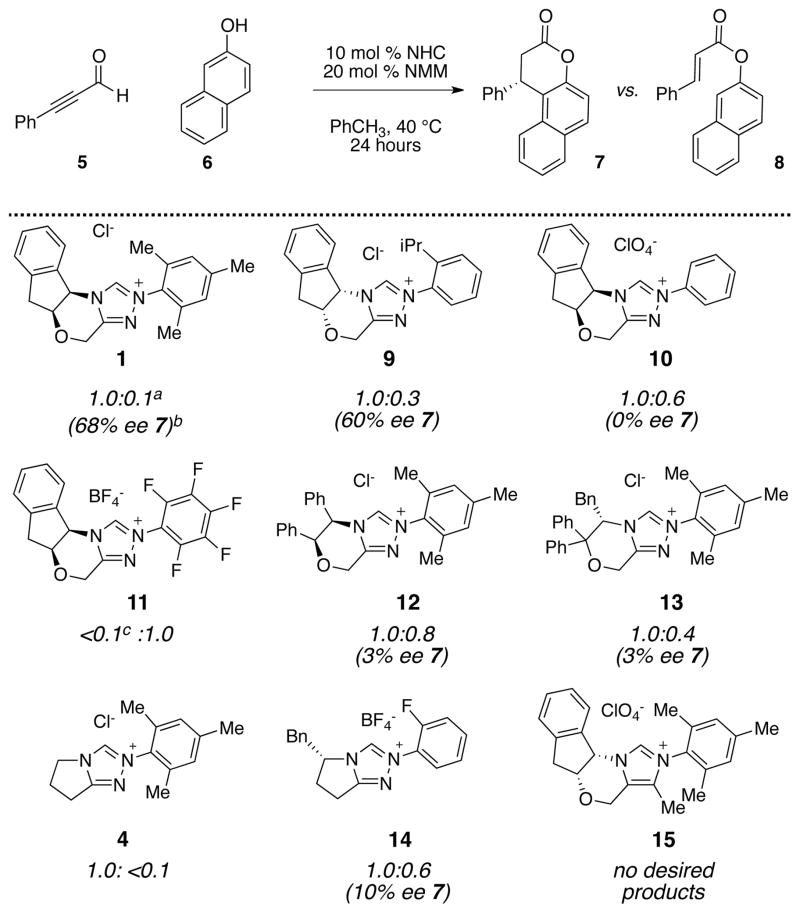

We commenced our investigations by examining the acylation of 2-naphthol 6 and ynal 5 with various NHC precatalysts and N-methyl morpholine (NMM) as a catalytic base. Two products were observed: annulation product 7 and ester product 8 (Table 1). Control experiments established that the ester product was not converted to the annulation product under these conditions. Instead, the catalyst structure played a critical role in determining the product outcome. Electron-deficient aryl groups on the triazolium core (11) favored esterification while N-mesityl substituent gave exclusively the annulation product. Other catalyst types gave a mixture of both. The choice of amine base played only a small role in determining the product distribution or enantioselectivity.

Table 1.

Initial investigation with 2-naphthol

|

The ratio of 7 to 8 was determined from 1H NMR spectra of the crude mixture after 24 hour.

Percent enantiomeric excess (% ee) was determined from SFC analyses.

% ee not determinable.

Although impressed with the ability of triazolium-derived carbenes to affect the desired annulation reaction, the sub-optimal enantioselectivies forced us to reconsider our approach. In particular, we wished to perform catalyst development or screening on a more synthetically relevant substrate. An examination of the vast literature on Claisen rearrangements identified enantioselective rearrangements of kojic acid derivatives as an unmet synthetic need. For example, Wender has established Claisen rearrangements of kojic acid as a useful synthetic platform for complex molecules synthesis but also noted the failure of traditional chiral Lewis acid approaches to the Claisen rearrangement of this particular substrate (Figure 1).49

Figure 1.

Wender’s elaboration of Kojic acid

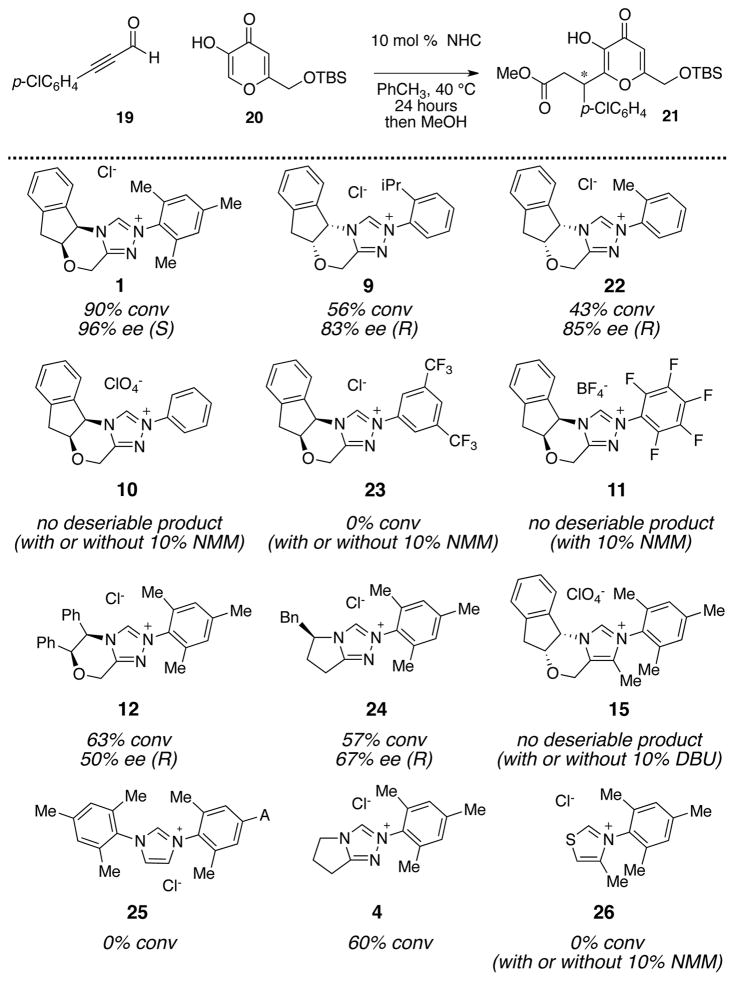

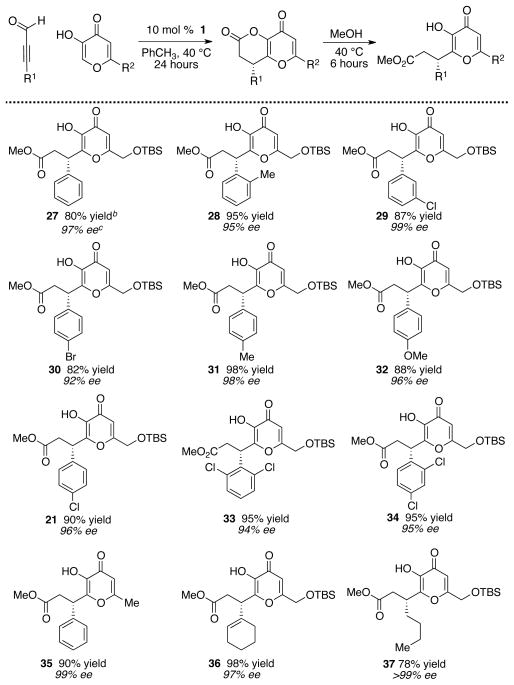

We were pleased to find that the combination of kojic acid 20, ynal 19, and an NHC precatalyst led to the formation of the desired dihydropyranone (Table 2). This product proved to be somewhat unstable towards isolation by column chromatography – a problem that was overcome by adding MeOH at the completion of the reaction and stirring for six hours, leading to the ring-opened products. In the course of our catalyst screening, we initially noted irreproducible outcomes with respective to the enantioselectivity. Control reactions showed that this issue arose from the propensity of this particular dihydropyranone adduct to undergo racemization, even in the presence of weak base or acid. This issue was alleviated by conducting the reactions without added base – a surprising but effective solution. This led to the optimized conditions: 1.0 equiv of kojic acid, 1.5 equiv ynal, and 10 mol % triazolium 1 at 40 °C in toluene for 24 hours. This base-free condition proved applicable to a full range of ynals with aliphatic, alkenyl, and aromatic substituents (Table 3). In nearly all cases examined, the desired product was obtained in excellent yield and enantiomeric excess.

Table 2.

|

Percentage conversion was determined from the 1H NMR of the crude mixture after 24 hour.

Percent enantiomeric excess was determined from SFC analyses.

Table 3.

Catalytic, enantioselective couplings with kojic acidsa

|

Reaction conditions: 0.1 M PhCH3, 24 h.

Yield refers to isolated yield after chromatography.

Absolute configuration determined by conversion to (S)-phenylsuccinic acid.

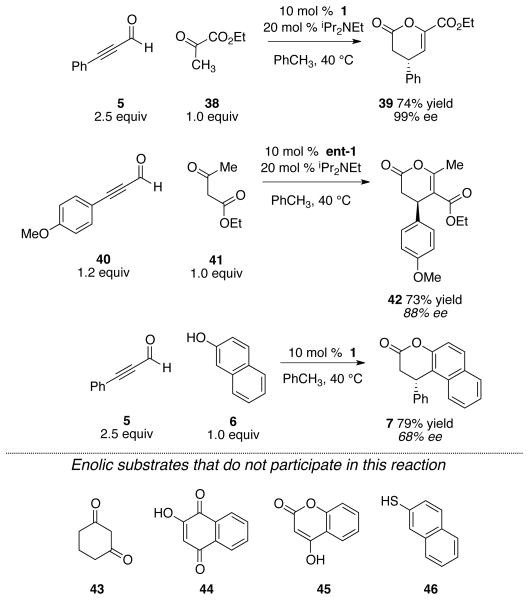

We sought to further expand the substrate scope with regards to the enolic components and found that other stable enols undergo NHC-catalyzed couplings with ynals to give the expected dihydropyranone products. Pyruvic ester 38 and ethyl 3-oxobutanoate 41 were excellent substrates, provided that a weak amine base is added to promote enol formation. 2-Naphthol gave the corresponding dihydropyranone products, albeit with diminished level of selectivity (Scheme 5). As expected from the work of others,28–35 cyclic 1,3-diketone 43 should give the desired product in respectable enantiomeric excess when 1 is used as precatalyst. To date, however, 43, 2-hydrodroxynaphthoquinone 44, hydroxycoumarin 45, or thionaphthol 46 were not suitable substrates in this variant of the Coates-Claisen reaction.

Scheme 5.

Catalytic, enantioselective couplings with other enol partners

Two general features of this N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed annulation deserve comment. First, in reactions with stable enols, including naphthol and kojic acid, no additional base was needed. This was attributed to the ability of the chloride counterion to serve as a base for generation of the active carbene; precatalysts with less basic counterions were not effective.51 Second, regardless of whether or not base was used only triazolium catalysts that bear at least one ortho-substitutent (1, 9, or 22; Table 2) were effective catalysts. Other azolium salts, such as imidazolium (15 or 25) or thiazolium (26) salts did not give the desired product. Some triazolium salts, such as the pentafluorophenyl substituted derivative 11, gave exclusively ester products (vide infra). Among the chiral triazolium scaffolds examined, the aminoindanol core pioneered by Rovis38 was uniquely effective in controlling the enantioselectivity. This was surprising, as other chiral scaffolds were often suitable for other classes of NHC-catalyzed annulations. It was also surprising that the aminoindanol core was again the superior choice, as this reaction involved a catalytically generated electrophilic species while all other NHC-catalyzed chemistry involved catalytically generated nucleophiles.

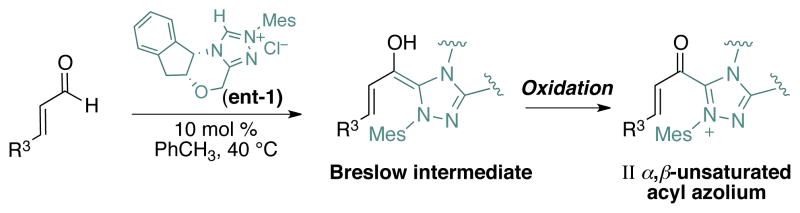

Although ynals proved to be the ideal substrates for our optimization studies and mechanistic investigations, the relative difficulty of synthesizing and storing these compounds render them less attractive starting materials than other substrates typically used in NHC-catalyzed reactions. In his related studies on NHC-catalyzed annulations, Lupton employed α,β-unsaturated acyl fluorides or enol esters, which generate the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium without redox chemistry.28–29 In the context of oxidative esterifications of cinnamaldehyde, Studer72 reported several examples of reactions that should proceed via the identical α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium species critical to the success of the Coates-Claisen reactions (Scheme 6). Indeed, we briefly explored the combination of enal and a stoichiometric oxidant as a route to these intermediates in our Communication. Studer has nicely demonstrated this approach as a general entry to racemic dihydropyranone synthesis.32

Scheme 6.

Catalytic generation of α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium from enal via the oxidation of the Breslow intermediate

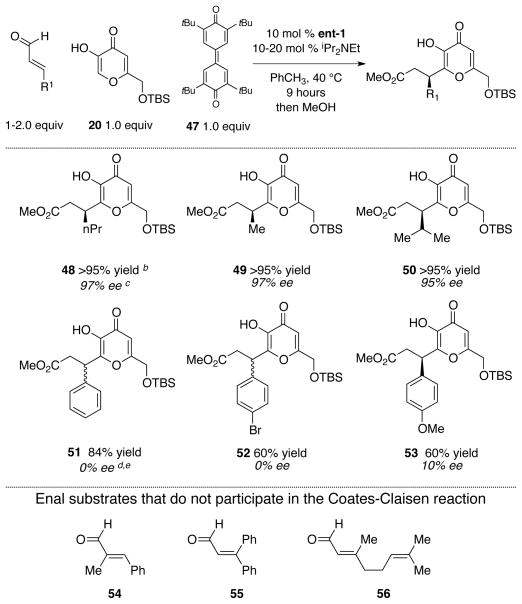

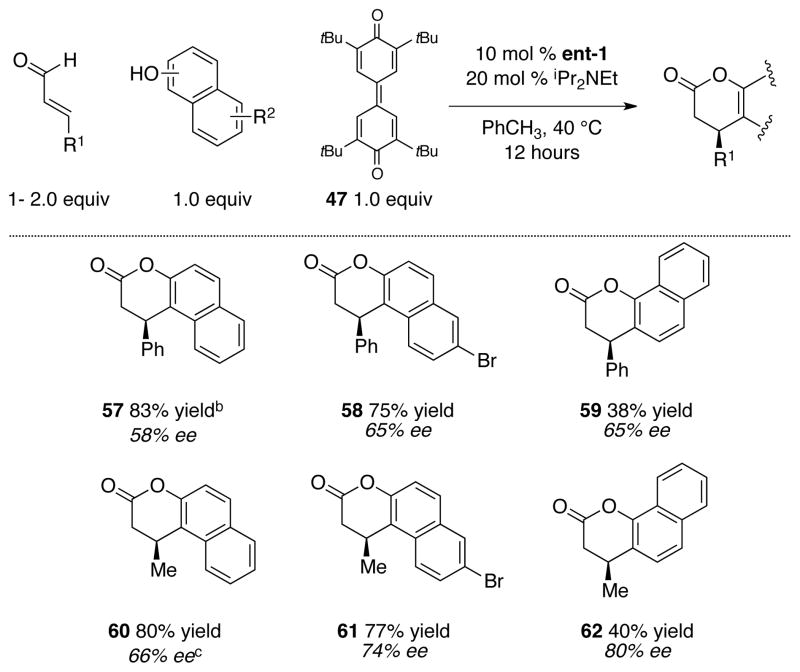

After a standard course of screening for suitable oxidant, we found that the oxidant 47 reported by Kharasch73 and utilized by Studer was a superior oxidant than phenazine,74 azobenzene,75 MnO2,76 TEMPO, 77 or air.78 Kojic acid derivative 20 proved again to be a good substrate for the coupling with both aliphatic and aromatic enals (regardless of the substitution) in this oxidative method. However, we noted the decrease in percent conversion in the absence of base. This was likely due to the decreased reactivity of enals, in comparison to the ynals, and the acidic phenolic proton of the reduced form of the oxidant, which caused catalyst inhibition. When a base such as iPr2NEt was employed, the catalyst reactivity was restored but racemization during the formation of the desired products 51 – 53 was observed. However, the use of base in conjunction with enal substrates bearing aliphatic side chain did not present a problem. This approach is the preferred route to aliphatic substituted products, both in terms of ease and availability of the starting enals (Table 4). In our hands, more substituted enals such as 54 – 56 did not currently work with kojic acid as a reaction partner. Additionally, we have demonstrated the generality of our methodology with various naphthols. Both 2- and substituted-naphthols proved to be viable substrates when coupling with either cinnamaldehyde or crotonaldehyde, although with a decrease in stereoselectivity. The enantiomeric excess was improved with 1-naphthol; however, byproducts were observed and led to diminished chemical yield (Table 5).

Table 4.

Catalytic, enantioselective couplings with enalsa

|

Reaction conditions: 0.1 M PhCH3, 9 h.

Yield refers to isolated yield after chromatography.

Absolute configuration was assigned by analogy from Table 3.

With 0.5 equiv of the 47 (without iPr2NEt), we obtained 50 % conv of the product (97% ee).

When 1.0 equiv of oxidant 47 was used (without iPr2NEt), we also 50 % conv of the product (88% ee).

Table 5.

Catalytic, enantioselective couplings with naphtholsa

|

Reaction conditions: 0.1 M PhCH3, 12 h.

Yield refers to isolated yield after chromatography.

Absolute configuration was assigned by comparison of the [α]D value with the literature value.

MECHANISTIC CONSIDERATION

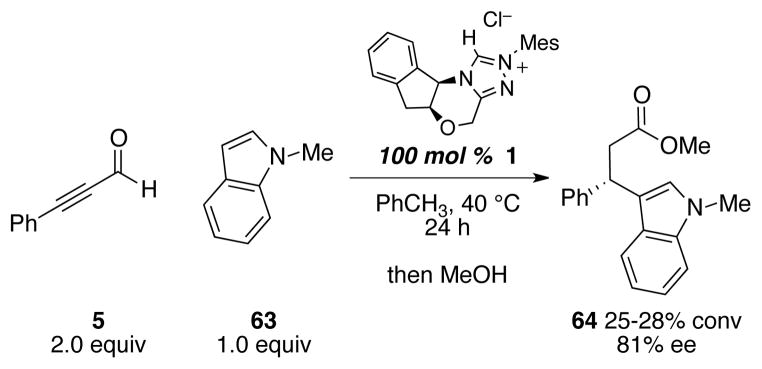

At the outset of our investigation into the reactivity of α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium, we anticipated that this transiently generated intermediate would serve as an excellent electrophile for conjugate addition reaction. This hypothesis was further supported by its postulated role in the biosynthesis of clavulinic acid, in which an α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium served as electrophile for the conjugate addition with amine.79 Our initial attempts at effecting conjugate additions with nucleophiles including thiols, azide, hydroxamic acids, and electron-rich aromatic compounds were unsuccessful. Upon further investigation of conjugate addition with 1-methylindole and α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium generated using stoichiometric amount of the NHC catalyst and in the absence of a competing nucleophile, we have since found that conjugate addition could be achieved (Scheme 7). Although the conversion was low, the formation of the expected product in respectable enantioselectivity demonstrated that the α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium is not precluded from the possibility of undergoing 1,4 addition with suitable nucleophile.80 The related annulations of α,β-unsaturated acyl azoliums and enols or enolates28–35 have all invoked this mechanistic paradigm.

Scheme 7.

A conjugate addition of 1-methylindole to α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium

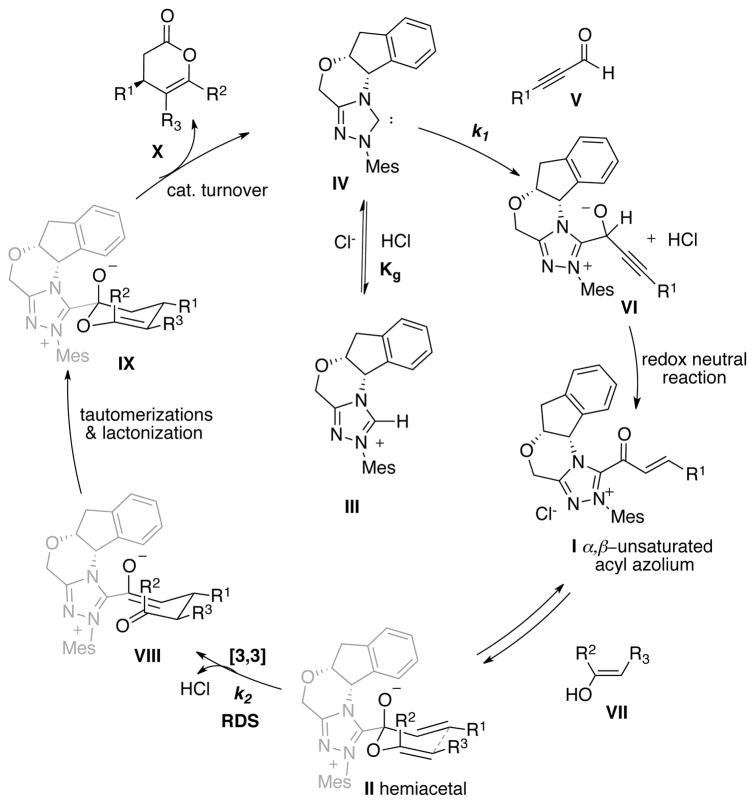

The much slower rate of 1-methylindole in comparison to stable enols (i.e. 20, 38, or 6) and the failure of almost all other good Michael donors (43–46) to give the expected conjugate addition products prompted us to consider the Coates-Claisen mechanism. Extensive investigations reported in our prior Communication established the catalytic cycle shown in Figure 2. The triazolium salt precatalyst (III) is deprotonated by a general base (i.e. the counter ion) to generate active NHC IV. This species adds irreversibly to aldehyde to form an adduct which readily undergoes a proton transfer and an internal redox reaction to form α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium I. Following the well-known chemistry of acyl azolium,59–65 this species and the enol are expected to be in equilibrium with hemiacetal II. According to a Coates-Claisen mechanism, this kinetically important hemiacetal undergoes a [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement to afford adduct VIII, which undergoes tautomerization and lactonization to effect catalyst turnover and deliver dihydropyranone product (X). Depicted in Figure 2, the key hemiacetal II is in an overall neutral form (with an oxy anion). It is also conceivable that hemiacetal II is protonated and exists as an ion pair with the counter ion (Cl−). An ongoing computational investigation to resolve this issue and its implication on enantioinduction will be disclosed in due course. As noted by both ourselves51 and Coates and Curran81 in their seminal investigations, it is not possible to completely distinguish between a “true” sigmatropic rearrangement and the breakdown of the acetal to a tight ion pair that undergoes a stepwise carbon–carbon bond forming process via a highly organized transition state. This mechanistic conundrum has been well-described for some Claisen reactions.2 The most accurate description of our reaction is perhaps an “ion-pair-Claisen-type” rearrangement.

Figure 2.

The catalytic cycle for NHC-catalyzed Claisen rearrangement from ynal and an enol

The derived and observed rate laws for the reaction of kojic acid 20 with 2,4-dichlorophenyl substituted ynal 65 are shown in Table 6. This experimental rate law is consistent with a derived one, which takes into consideration the generation of the NHC from the azolium, a steady-state approximation of the initial aldehyde–NHC adduct, and the rapid equilibrium between I and its hemiacetal II.82 The derived rate law also rationalizes partial rate orders of the reaction both in the aldehyde and the kojic acid (expressed as a general acid HX), which inhibits the generation of the N-heterocyclic carbene.83, 84, 85

Table 6.

Rate laws for NHC-catalyzed Claisen rearrangement

| |

|---|---|

| Empirical rate law (from above):

| |

| Derived rate law (from Figure 2):

|

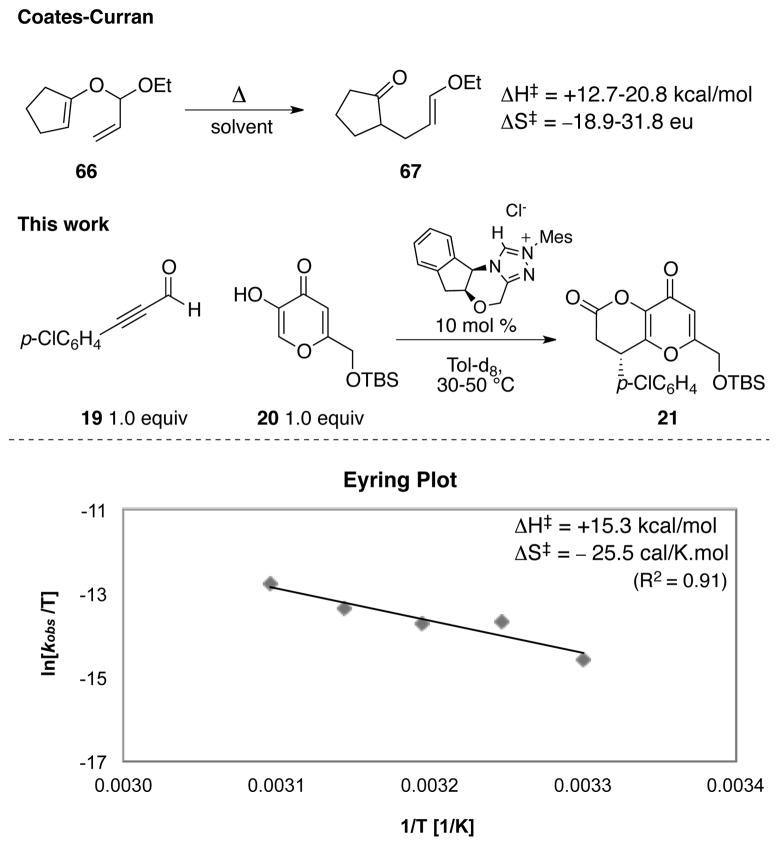

We proceeded to determine the activation parameters via an Eyring analysis using the empirical rate law above. The NHC-catalyzed variant of the Coates-Claisen reaction has an activation enthalpy of 15.3 kcal/mol and activation entropy of −25.5 cal/K•mol (Figure 3). Both the activation enthalpy and entropy are consistent with those observed by Coates and Curran81 (ΔH‡ from 12.7 to 20.8 kcal/mol and ΔS‡ from −18.9 to −31.8 eu). A large negative activation entropy is usually associated with an organized transition state, which also supported the proposed [3,3]-sigmatropic mechanism.

Figure 3.

The activation parameters for Coates-Claisen reaction and the NHC-catalyzed variant

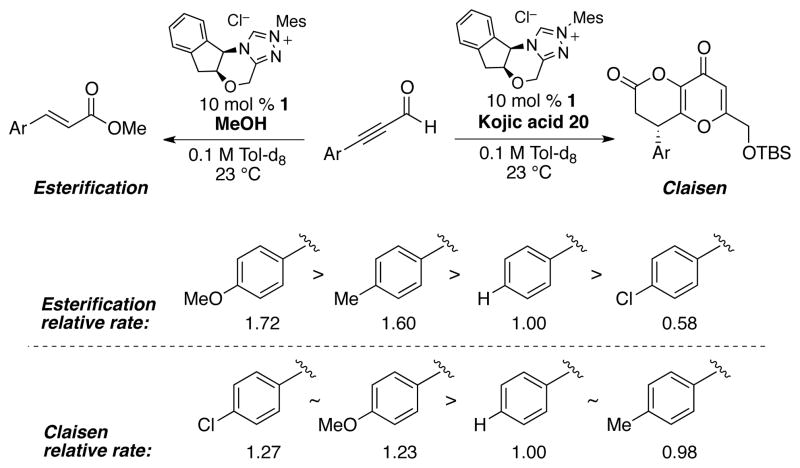

A rate study comparing the relative reactivity of various para-substituted ynals for the Claisen rearrangement revealed no Hammett trend, while linear free-energy relationship was observed for the redox esterification reaction of ynals71 (Scheme 8). The lack of Hammett trend for the Claisen rearrangement was somewhat unexpected, and we attributed this observation to ground state stabilization of α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium, rather than a change in the mechanism.86 Despite of this, the difference in the reactivity of ynals between these two reactions proceeding via common hemiacetal intermediates allowed us to rule out catalyst turnover (which is the rate-determining step of the redox esterification71) as the rate-limiting step for this annulation reaction.

Scheme 8.

Ynals reactivity comparison

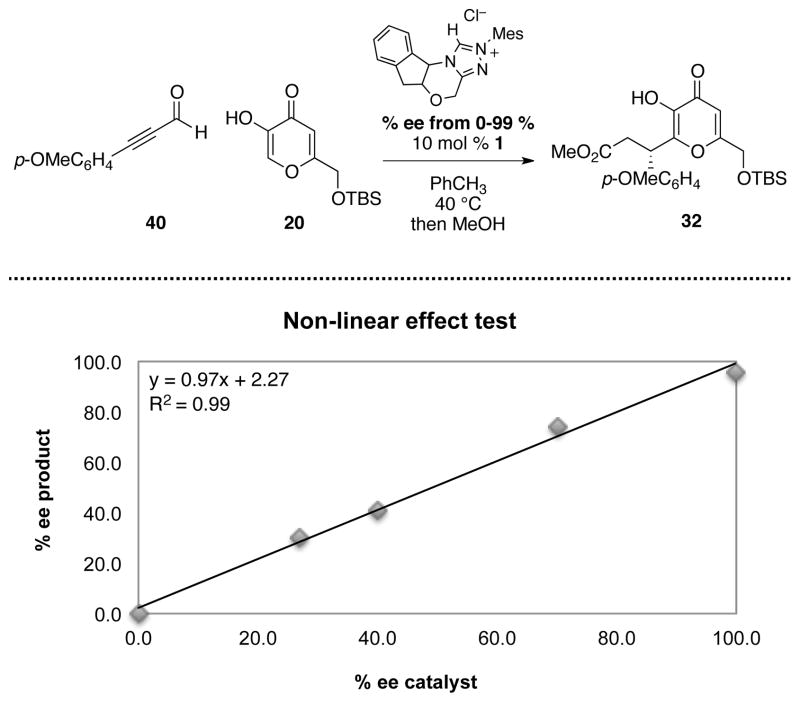

As pointed out by a referee in our Communication, the negative order of kojic acid 20 in the observed rate law could arise by a mechanism in which the N-heterocyclic carbene played an active role in activating the nucleophile. For example, in the acylation reaction of acyl azoliums with alcohols – a process that involves similar intermediates as this annulation – it was proposed that the NHC-activated the alcohol towards nucleophilic attack.66, 87 This implies that two molecules of the catalyst would be involved in the key bond-forming step. To test this, we briefly examined our annulation reaction for nonlinear effect using precatalyst 1 with varying degrees of enantiopurity. No such effect was observed, suggesting a single role for the catalyst in this reaction (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

An investigation on non-linear effect.

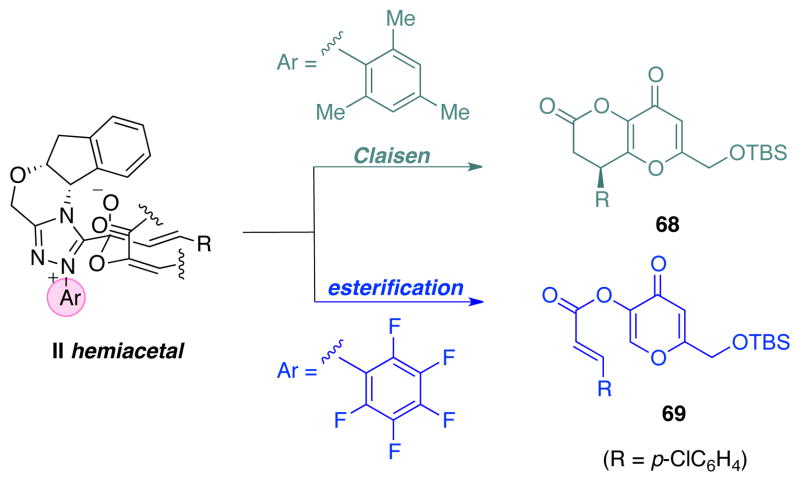

The last remaining question, which cannot be directly answered by kinetic studies, concerns the nature of the catalytic Claisen rearrangement. Does the N-mesityl triazolium catalyst play a role in lowering the activation barrier to the sigmatropic rearrangement? Or does it simply serve as a chiral auxiliary for controlling the stereochemistry of the rearrangement? From our initial catalyst screening, we found intriguingly that the aminoindanol derived triazolium salt 1 bearing the N-mesityl group affected the desired annulation cascade while the otherwise identical triazolium salt 11 bearing an N-C6F5 group cleanly afforded ester 69 as the sole product via a redox-neutral reaction (Scheme 9). Based on this finding, we propose that the mesityl moiety of the catalyst raises the activation barrier of the competing esterification and effectively prolongs the lifetime of the hemiacetal II, while the chiral aminoindanol moiety induces enantioselectivity by favoring one of the possible diastereomeric transition states for the Claisen rearrangement. In contrast, the N-C6F5 group made its corresponding carbene a better leaving group, accelerating the C-C bond cleavage during catalyst turnover (by lowering its energetic barrier). This mechanistic bifurcation was observed for the coupling of ynals with both kojic acid derivative 20 and 2-naphthol 6 (Table 1). The origin of these two catalysts’ divergency has been extensively investigated.88

Scheme 9.

Catalyst-controlled product selectivity: Claisen reaction vs. esterification

CONCLUSION

We have reported herein the development of a chiral N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed Coates-Claisen rearrangement. This reaction generally proceeded with a broad substrate scope and in many case with very high level of enantioselectivity. The key α,β-unsaturated acyl azolium intermediate was accessible via NHC catalyzed redox neutral reaction of ynals or oxidative reaction of enals. The synthetic utility of this methodology has also been demonstrated in the context of the functionalization of kojic acid derivatives, ready for further elaboration into compounds of contemporaneous interest. Detailed kinetic analysis provided insights into the nuances and the complex nature of the mechanism of this NHC catalyzed annulation reaction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: We are grateful to National Institutes of Health (GM–079339), ETH Zürich, Novartis (predoctoral fellowship for J.M.), and the Royal Thai Government (predoctoral fellowship for J.K.) for financial support.

The authors thank Darko Santrac for preliminary investigations and Pinguan Zheng for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information available on the Internet. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

References

- 1.Claisen L. Ber. 1912;45:3157–3166. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hiersemann M, Nubbemeyer U, editors. The Claisen Rearrangment. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welch JT, Eswarakrishnan S. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:6716–6719. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maruoka K, Banno H, Yamamoto H. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:7791–7793. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corey EJ, Lee DH. J Am Chem Soc. 1991;113:4026–4028. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham L, Czerwonka R, Hiersemann M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2001;40:4700–4703. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4700::aid-anie4700>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiersemann M, Abraham L. Org Lett. 2000;3:49–52. doi: 10.1021/ol006760w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoon TP, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:2911–2912. doi: 10.1021/ja015612d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akiyama K, Mikami K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:7217–7220. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linton EC, Kozlowski MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:16162–16163. doi: 10.1021/ja807026z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao T, Deitch J, Linton EC, Kozlowski MC. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012 doi: 10.1002/anie.201107417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gille A, Rehbein J, Hiersemann M. Org Lett. 2011;13:2122–2125. doi: 10.1021/ol200558j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson SG, Bungard CJ, Wang K. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:13000–13001. doi: 10.1021/ja037655v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nelson SG, Wang K. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:4232–4233. doi: 10.1021/ja058172p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geherty ME, Dura RD, Nelson SG. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11875–11877. doi: 10.1021/ja1039314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kienhöfer A, Kast P, Hilvert D. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:3206–3207. doi: 10.1021/ja0341992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles RR, Jacobsen EN. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20678–20685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006402107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreiner PR. Chem Soc Rev. 2003;32:289–296. doi: 10.1039/b107298f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran DP, Kuo LH. Tetrahedron Lett. 1995;36:6647–6650. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirsten M, Rehbein J, Hiersemann M, Strassner T. J Org Chem. 2007;72:4001–4011. doi: 10.1021/jo062455y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annamalai VR, Linton EC, Kozlowski MC. Org Lett. 2008;11:621–624. doi: 10.1021/ol8026945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uyeda C, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9228–9229. doi: 10.1021/ja803370x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uyeda C, Rötheli AR, Jacobsen EN. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:9753–9756. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uyeda C, Jacobsen EN. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5062–5075. doi: 10.1021/ja110842s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiang P-C, Bode JW. N-Heterocyclic Carbenes. The Royal Society of Chemistry; 2011. pp. 399–435. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nair V, Menon RS, Biju AT, Sinu CR, Paul RR, Jose A, Sreekumar V. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5336–5346. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15139h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore JL, Rovis T. Top Curr Chem. 2009;291:77–144. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-02815-1_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan SJ, Candish L, Lupton DW. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14176–14177. doi: 10.1021/ja905501z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Candish L, Lupton DW. Org Lett. 2010;12:4836–4839. doi: 10.1021/ol101983h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu ZQ, Xiao JC. Adv Syn Catal. 2010;352:2455–2458. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu Z-Q, Zheng X-L, Jiang N-F, Wan X, Xiao J-C. Chem Commun. 2011;47:8670–8672. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12778k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Sarkar S, Studer A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:9266–9269. doi: 10.1002/anie.201004593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biswas A, Sarkar SD, Frohlich R, Studer A. Org Lett. 2011;13:4966–4969. doi: 10.1021/ol202108a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rong Z-Q, Jia M-Q, You S-L. Org Lett. 2011;13:4080–4083. doi: 10.1021/ol201595f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun F-G, Sun L-H, Ye S. Adv Synth Catal. 2011;353:3134–3138. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan SJ, Candish L, Lupton DW. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4694–4697. doi: 10.1021/ja111067j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enders D, Breuer K, Teles JH. Helv Chim Acta. 1996;79:1217–1221. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerr MS, Read de Alaniz J, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10298–10299. doi: 10.1021/ja027411v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sohn SS, Rosen EL, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:14370–14371. doi: 10.1021/ja044714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burstein C, Glorius F. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:6205–6208. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He M, Struble JR, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8418–8420. doi: 10.1021/ja062707c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaeobamrung J, Kozlowski MC, Bode JW. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:20661–20665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007469107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chow Y-K, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:8126–8127. doi: 10.1021/ja047407e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reynolds NT, Read de Alaniz J, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9518–9519. doi: 10.1021/ja046991o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khaleeli N, Li R, Townsend CA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9223–9224. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coates RM, Shah SK, Mason RW. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:2198–2208. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Coates RM, Hobbes SJ. J Org Chem. 1984;49:140–152. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McDonald FE, Wender PA. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4956–4958. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wender PA, D’Angelo N, Elitzin VI, Ernst M, Jackson-Ugueto EE, Kowalski JA, McKendry S, Rehfeuter M, Sun R, Voigtlaender D. Org Lett. 2007;9:1829–1832. doi: 10.1021/ol0705649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wender PA, Buschmann N, Cardin NB, Jones LR, Kan C, Kee J-M, Kowalski JA, Longcore KE. Nature Chem. 2011;3:615–619. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaeobamrung J, Mahatthananchai J, Zheng P, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8810–8812. doi: 10.1021/ja103631u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wanner B, Mahatthananchai J, Bode JW. Org Lett. 2011;13:5378–5381. doi: 10.1021/ol202272t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.After his early reports (reference 28 and 29), Lupton has demonstrated the Claisen mechanism to be a viable pathway for certain substrates: Candish L, Lupton DW. Org Biomol Chem. 2011;9:8182–8189. doi: 10.1039/c1ob05953j.

- 54.Candish L, Lupton DW. Chem Sci. 2012;3:380–383. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sohn SS, Bode JW. Org Lett. 2005;7:3873–3876. doi: 10.1021/ol051269w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bode JW, Sohn SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13798–13799. doi: 10.1021/ja0768136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiang P-C, Kim Y, Bode JW. Chem Commun. 2009:4566–4568. doi: 10.1039/b909360e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Binanzer M, Hsieh S-Y, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19698–19701. doi: 10.1021/ja209472h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Breslow R, McNelis E. J Am Chem Soc. 1960;82:2394–2395. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Daigo K, Reed LJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:659–662. [Google Scholar]

- 61.White FG, Ingraham LL. J Am Chem Soc. 1962;84:3109–3111. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bruice TC, Kundu NG. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:4097–4098. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lienhard GE. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:5642–5649. doi: 10.1021/ja00969a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Owen TC, Richards A. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:2520–2521. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Owen TC, Harris JN. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:6136–6137. [Google Scholar]

- 66.This unusual chemoselectivity has been exploited in acylation reaction of alcohol in the presence of amine: Movassaghi M, Schmidt MA. Org Lett. 2005;7:2453–2456. doi: 10.1021/ol050773y.

- 67.Vora HU, Rovis T. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:13796–13797. doi: 10.1021/ja0764052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.The issue of selective O-acylation vs. C-alkylation of enolate has been investigated in Zhong M, Brauman JI. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:636–641.

- 69.Chiang P-C, Kaeobamrung J, Bode JW. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3520–3521. doi: 10.1021/ja0705543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zeitler K. Org Lett. 2006;8:637–640. doi: 10.1021/ol052826h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mahatthananchai J, Zheng P, Bode JW. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:1673–1677. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Sarkar S, Grimme S, Studer A. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1190–1191. doi: 10.1021/ja910540j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kharasch MS, Joshi BS. J Org Chem. 1957;22:1439–1443. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Inoue H, Higashiura K. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1980:549–550. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Noonan C, Baragwanath L, Connon SJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:4003–4006. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Maki BE, Chan A, Phillips EM, Scheidt KA. Org Lett. 2006;9:371–374. doi: 10.1021/ol062940f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guin J, De Sarkar S, Grimme S, Studer A. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2008;47:8727–8730. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiang P-C, Bode JW. Org Lett. 2011;13:2422–2425. doi: 10.1021/ol2006538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Merski M, Townsend CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15750–15751. doi: 10.1021/ja076704r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lupton and coworkers have methodically elucidated that their formal [4+2] annulation reaction operates through a Michael-type addition via computational and secondary kinetic isotope effect studies: Ryan SJ, Stasch A, Paddon-Row MN, Lupton DW. J Org Chem. 2012;77:1113–1124. doi: 10.1021/jo202500k.

- 81.Coates RM, Rogers BD, Hobbs SJ, Peck DR, Curran DP. J Am Chem Soc. 1987;109:1160–1170. [Google Scholar]

- 82.For a full discussion of the rate laws, we direct the readers to reference 51 and 71.

- 83.Coulembier O, Lohmeijer BGG, Dove AP, Pratt RC, Mespouille L, Culkin DA, Benight SJ, Dubois P, Waymouth RM, Hedrick JL. Macromolecules. 2006;39:5617–5628. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Myles L, Gore R, Spulak M, Gathergood N, Connon SJ. Green Chem. 2010;12:1157–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hollóczki O, Terleczky P, Szieberth D, Mourgas G, Gudat D, Nyulászi L. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;133:780–789. doi: 10.1021/ja103578y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Um I-H, Han H-J, Ahn J-A, Kang S, Buncel E. J Org Chem. 2002;67:8475–8480. doi: 10.1021/jo026339g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Sarkar S, Biswas A, Song CH, Studer A. Synthesis. 2011;12:1974–1983. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mahatthananchai J, Bode JW. Chem Sci. 2012;3:192–197. doi: 10.1039/C1SC00397F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.