Abstract

Phytosteryl glycosides occur in natural foods but little is known about their metabolism and bioactivity. Purified acylated steryl glycosides (ASG) were compared with phytosteryl esters (PSE) in mice. Animals on a phytosterol-free diet received ASG or PSE by gavage in purified soybean oil along with tracers cholesterol-d7 and sitostanol-d4. In a three-day fecal recovery study, ASG reduced cholesterol absorption efficiency by 45 ± 6% compared with 40 ± 6% observed with PSE. Four hours after gavage, plasma and liver cholesterol-d7 levels were reduced 86% or more when ASG was present. Liver total phytosterols were unchanged after ASG administration but were significantly increased after PSE. After ASG treatment both ASG and deacylated steryl glycosides (SG) were found in the gut mucosa and lumen. ASG was quantitatively recovered from stool samples as SG. These results demonstrate that ASG reduces cholesterol absorption in mice as efficiently as PSE while having little systemic absorption itself. Cleavage of the glycosidic linkage is not required for biological activity of ASG. Phytosteryl glycosides should be included in measurements of bioactive phytosterols.

Keywords: Stable isotopes, Plant sterols, Mass spectrometry, Lipid absorption

Introduction

Phytosterols are structurally similar to cholesterol, occur naturally in plant-derived foods, and reduce cholesterol absorption [1-4] and plasma LDL-cholesterol [5, 6]. Because of these potentially beneficial health effects, the US National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III has recommended adding 2.0 g/day phytosterols to the diet of adults to reduce LDL-cholesterol and coronary heart disease risk [7, 8].

To reach the 2.0 g/day of phytosterols, pure phytosterols (free or esters) have been routinely added to various functional foods. The chemical or physical form of the phytosterol is potentially important for bioactivity because crystalline phytosterols are not readily soluble in bile and do not reduce cholesterol absorption [9]. When properly formulated with lecithin or other emulsifiers, free phytosterols do reduce cholesterol absorption and plasma LDL cholesterol [10]. Phytosteryl esters solubilized in the tri-glyceride phase of margarines are also bioactive [11, 12].

Phytosterols are conjugated to various components in food matrices and not all have been tested for bioactivity [13]. Recently, we have demonstrated that pure phytosteryl esters supplemented at an amount achievable from a diet (459 mg phytosterols/day) reduce cholesterol absorption and increase fecal cholesterol excretion in humans [14]. Furthermore, phytosterols present in natural food matrices (449 mg/day) are also bioactive in reducing cholesterol absorption and enhancing fecal cholesterol excretion [15]. Because phytosteryl glycosides comprise a significant proportion of naturally occurring phytosterols in some foods [16-18], we have studied them and demonstrated that phytosteryl glycosides (mostly acylated steryl glycosides, ASG) purified from soybean-derived lecithin reduce cholesterol absorption efficiency in humans [19]. However, several questions remain unanswered regarding their mechanisms of action. Phytosteryl glycosides could act intact, as glycosides (with the fatty acid cleaved), or as free phytosterols (with both fatty acid and glucose cleaved).

ASG consist of a fatty acid and a glucose moiety in addition to the phytosterol [19]. Previous work has shown that fatty acids are cleaved from glycosylated phytosterols in vitro by pancreatin and cholesterol esterase but the sugar moiety itself is not removed [20]. Acetylated 14C-sitosteryl glucoside was not absorbed in the stomach or small bowel of rats after intragastric administration [21]. However, the 14C label was located in the phytosterol moiety, which did not enable the authors to answer whether or not any cleavage had occurred in vivo.

In this study we prepared purified ASG and tested the hypotheses that ASG is active in reducing cholesterol absorption efficiency in mice and that it is cleaved to SG or free phytosterols in mice consuming a cholesterol and phytosterol-free diet.

Materials and Methods

Materials

[25,26,26,26,27,27,27-2H7]Cholesterol (cholesterol-d7) was purchased from CDN Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada). Soybean oil (Bakers & Chefs, Sam’s Club) was purified as described elsewhere [3] to reduce the content of phytosterols. [5,6,22,23-2H4]sitostanol (sitostanol-d4) was obtained from Medical Isotopes (Pelham, NH, USA). The phytosteryl glycosides were partially purified from lecithin granules (Vitamin Shoppe, North Bergen, NJ, USA) as previously described [19]. Crude phytosteryl glycosides were then dissolved in hexane and applied to a Supelclean LC-Si SPE column (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) that had been conditioned with hexane. The column was eluted with 30% ethyl acetate in hexane, followed by 50% ethyl acetate in hexane. The material in the second elution was ASG without free phytosterols, phytosteryl esters, or phospholipids. ASG contained 48.5% phytosterols by weight. Phytosteryl esters (PSE) were derived from soy and 60.6% of the mass was the phytosteryl moiety. ASG and SG for HPLC standards were obtained from Matreya (Pleasant Gap, PA, USA).

Mice

Male C57BL/6J mice (5 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were housed in a room maintained at 24°C with a 12:12 h light–dark cycle (6:00 a.m.−6:00 p.m.). All mice were fed first on Purina mouse chow 5053 containing 4.5% fat, 20.0% protein, and 54.8% carbohydrate (LabDiet) for one week before switching to the sterol-free diet. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with guidelines of Washington University’s Animal Studies Committee and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Washington University (study protocol: 20070024).

Effect of a Single-Dose ASG/PSE on Cholesterol Absorption Over a Three-Day Period

Mice (5 each for control, PSE, or ASG) were fed a special cholesterol and phytosterol-free diet [22] for two weeks to minimize the effects of dietary sterols. Each mouse was gavaged with 0.5 mL purified soybean oil containing 40 μg cholesterol-d7 and 10 μg sitostanol-d4. The oil also contained 1.0 mg phytosterols delivered as either phytosteryl esters or glycosides or no addition (control). Stool samples from each mouse was collected individually in a cage with wire floor for three days. Mice were approximately eight weeks old at the time of experimentation.

Single-Time-Point Oral Study

Male C57BL/6J mice were equilibrated on the sterol-free diet and then fasted for 2 h before gavage of 0.5 mL purified soybean oil with 40 μg cholesterol-d7 containing 6.1 mg phytosterols given as either phytosteryl esters (PSE, n = 5) or phytosteryl glycosides (ASG, n = 5), or oil only (control, n = 5). Mice were sacrificed 4 h after gavage. Blood was obtained by heart puncture and centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 5 min to obtain serum. The liver and small intestine were removed and the small intestine was divided into four equal segments, lumenal contents were washed out and collected with ice-cold PBS. After the small bowel was opened longitudinally, the mucosa was extruded from the bowel wall by exerting pressure using a microscopic slide.

Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

For the cholesterol absorption study, lipids were extracted from stool samples by the Bligh and Dyer method [23], hydrolyzed in alkali, and the neutral sterols were extracted into petroleum ether, dried, and converted to penta-fluorobenzoyl esters [24]. The derivatized material was analyzed for cholesterol-d7, coprostanol-d7, and sitostanol-d4 by negative-ion chemical ionization gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) [14]. For the single-time-point oral study, 40 μg sitostanol-d4 was added as an internal recovery standard and lipids were extracted [23] from liver, lumen washings, and mucosa; aliquots of extracted lipids were processed by both acid and alkaline hydrolysis as described elsewhere [25] and analyzed by GC–MS [26]. Plasma was analyzed as described for liver, lumen washings, and mucosa without undergoing lipid extraction. Acid hydrolysis liberates free phytosterols from ASG and SG whereas alkaline hydrolysis does not.

ASG/SG Analysis

The ASG/SG contents of lumenal and mucosal samples and stool samples were analyzed by HPLC with an evaporative light scattering detector, exactly as described elsewhere [27]. A standard curve using ASG and SG standards was constructed and used to calculate the amount of ASG and SG in the samples.

Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as means ± SEM. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS (version 9.2; Cary, NC, USA). The Proc Mixed procedure was used to analyze treatment effects on cholesterol absorption and cholesterol-d7 levels in liver and plasma with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons. Proc Mixed was also used to analyze the independent effect of treatments and quarters and their interactions. Statistical significance was accepted if P < 0.05, or otherwise as indicated.

Results

Purity of Phytosteryl Glycosides

Phytosteryl glycosides were obtained from lecithin granules by removing most of the phospholipids and neutral sterols [19]. To further increase purity the material was passed through a Supelclean LC-Si SPE column. Thin layer chromatographic analysis showed no detectable sterols or phospholipids (data not shown). The purified phytosteryl glycosides contained mostly ASG (92.5%) and a smaller fraction of SG (7.5%) by HPLC. Campesterol, stigmasterol, and sitosterol accounted for 27.3 ± 0.5, 21.4 ± 0.2, and 51.6 ± 0.8% of total phytosterols, respectively, for the phytosteryl esters; corresponding values for the phytosteryl glycosides were 21.3 ± 0.8, 17.5 ± 0.5, and 53.9 ± 1.2%.

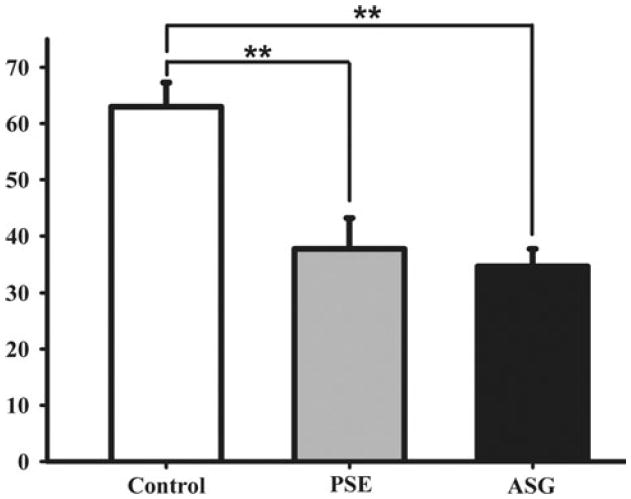

Effect of ASG on Percent Cholesterol Absorption in Mice

To determine whether phytosteryl glycosides were bioactive in reducing cholesterol absorption efficiency [19], we gavaged mice with ASG (1.0 mg phytosterols) solubilized in purified soybean oil. PSE (1.0 mg phytosterols) was administered in the same way as an experimental positive control and purified soybean oil alone was given to another group as a negative control. As expected, relative to control, PSE reduced cholesterol absorption by 40 ± 6% in a three-day fecal recovery experiment (Fig. 1). ASG reduced cholesterol absorption by 45 ± 6% when compared with control. The difference between ASG and PSE treatment groups was not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Three-day study: effect of ASG on percent cholesterol absorption in mice. Mice were gavaged with purified soybean oil containing ASG (1.0 mg phytosterols), PSE (1.0 mg phytosterols), or no addition (n = 5 for each group). Percent cholesterol absorption was determined as described in “Materials and Methods”. Bars represent means ± SE. Significance of differences between treatments is indicated by **(P < 0.01)

Single-Time-Point Oral Study

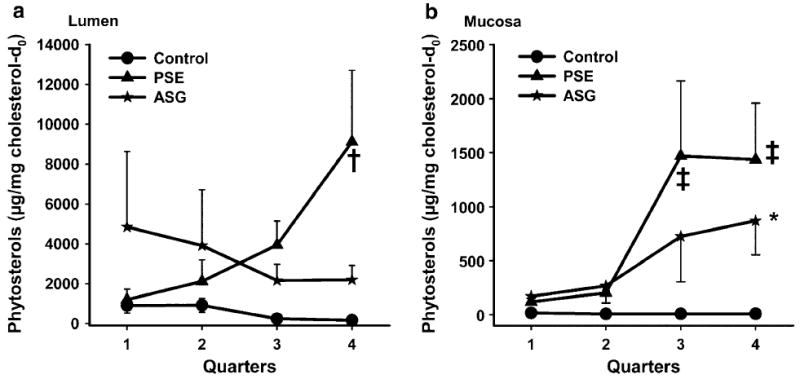

To explore the site where ASG reduced cholesterol absorption efficiency, groups of mice were gavaged with soybean oil containing ASG (6.1 mg phytosterols), PSE (6.1 mg phytosterols), or no addition and sacrificed 4 h later. Figures 2 and 3 report the levels of phytosterols, ASG, and SG found in the gut, lumen, and mucosa by quarter of small intestine. When no phytosterols were included in the gavage the measured phytosterol levels were very low, demonstrating the effectiveness of the prior two-week low-phytosterol baseline diet in reducing background. When either ASG or PSE was given, the total phytosterols found in the lumen (which included those present in the form of ASG and SG) were elevated and there was a significant treatment effect on total lumenal phytosterols (P = 0.0088, Fig. 2a). There was no significant relation of intestinal quarter to lumenal phytosterols (P = 0.54). Figure 2b shows that phytosterols accumulated in the mucosa after both ASG and PSE gavage. Total phytosterol content was largest in quarters 3 and 4 and was similar for the two phytosterol forms. There were statistically significant and independent effects of quarter (P = 0.012) and treatment (P = 0.0039) on total mucosal phytosterols.

Fig. 2.

Single-time-point study: total phytosterols in lumen (panel a) and mucosa (b). Mice (n = 5 for each group) were fasted for 2 h before gavage of purified soybean oil with cholesterol-d7 containing ASG (6.1 mg phytosterols), PSE (6.1 mg phytosterols), or no addition. Mice were sacrificed 4 h later, the small intestine was cut into four equal quarters (quarter 1: proximal, quarter 4: distal), and mucosa was scraped after removal of lumenal contents. Levels of total phytosterols relative to natural cholesterol in the lumen and mucosa were determined by GC–MS as described in “Materials and Methods”. Values are means ± SE. Statistical significance is indicated by †(P < 0.05) or ‡(P < 0.01) (between control and PSE) and by *(P < 0.05) (between control and ASG)

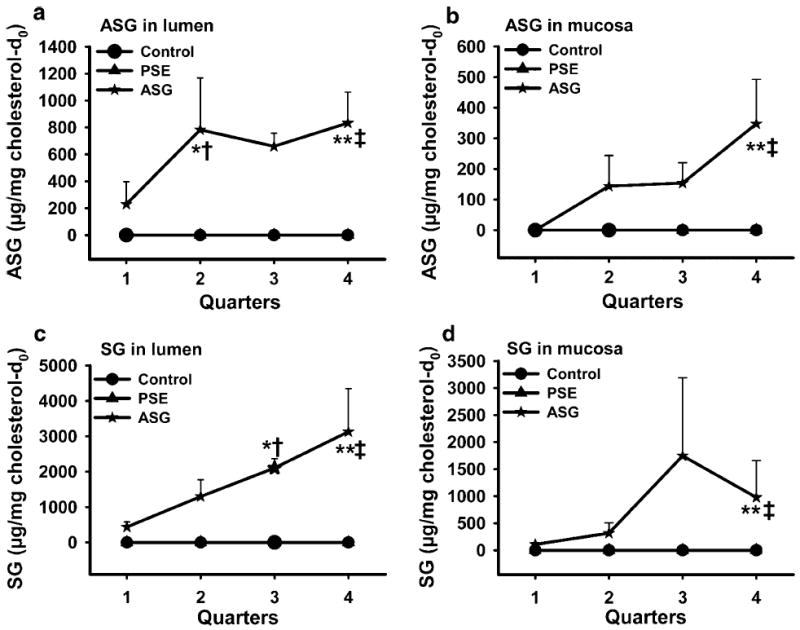

Fig. 3.

Single-time-point study: ASG and SG in lumen and mucosa. Mice (n = 5 for each group) were fasted for 2 h before gavage of purified soybean oil with cholesterol-d7 containing ASG (6.1 mg phytosterols), PSE (6.1 mg phytosterols), or no addition. Mice were sacrificed 4 h later, the small intestine was cut into four equal quarters (quarter 1: proximal, quarter 4: distal), and mucosa was scraped after removal of lumenal contents. The levels of directly measured ASG and SG relative to natural cholesterol in lumen and mucosa were determined as described in “Materials and Methods”. Values are means ± SE. Significance is indicated by *(P < 0.05) or **(P < 0.01) (between control and ASG) and by †(P < 0.05) or ‡(P < 0.01) (between PSE and ASG). Symbols for control and PSE overlap near zero

Further studies were performed to determine the chemical form of phytosterols present in lumen and mucosa after ASG treatment. Differential hydrolysis strongly suggested that they were present as glycosides. While combined acid + alkaline hydrolysis enables total phytosterols to be measured, alkaline hydrolysis alone does not liberate free phytosterols from glycosides to be measured by GC–MS. Phytosterols from lumen and mucosa after ASG treatment determined after alkaline-only hydrolysis were very low and similar to those in the control group (data not shown), suggesting that the total phytosterols reported in Fig. 2 after ASG treatment were derived from glycosylated phytosterols. This was confirmed by direct HPLC measurement of ASG and SG in intestinal fractions (Fig. 3; Table 1). As expected, after PSE or control gavage there was no detectable ASG or SG in the lumen or mucosa. However, after ASG gavage both ASG and SG were present in lumen and mucosa. The amount of SG exceeded that of ASG in all quarters, showing active but incomplete hydrolysis of the fatty acid of ASG to yield the deacylated product SG. In other experiments in which stools were collected for three days and analyzed by HPLC, the biological hydrolysis of ASG to SG was complete (Table 1). Recovery of SG in stool samples was 95.3 ± 1.9% of the ASG given. No detectable SG was found in stool samples from control or PSE groups.

Table 1.

Phytosterol recovery in the form of steryl glycosides from stool samples three days after gavage

| Control (n = 5) | PSE (n = 5) | ASG (n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total phytosterol gavaged (μg) | 27.9 ± 0.6 | 1034.2 ± 37.3 | 852.1 ± 19.7 |

| Phytosterols contained in SG (μg) | ND | ND | 810.8 ± 11.7 |

| Recovery rate in the form of SG (%) | NA | NA | 95.3 ± 1.9 |

C57BL/6J male mice (nine weeks old) were gavaged with 0.5 mL soybean oil alone (control, n = 5), 0.5 mL soybean oil with phytosteryl esters (PSE, n = 5) containing 1.0 mg phytosterols, and 0.5 mL soybean oil with phytosteryl glycosides (ASG, n = 5) with 1.0 mg phytosterol equivalents. SG was determined as described in “Materials and Methods”

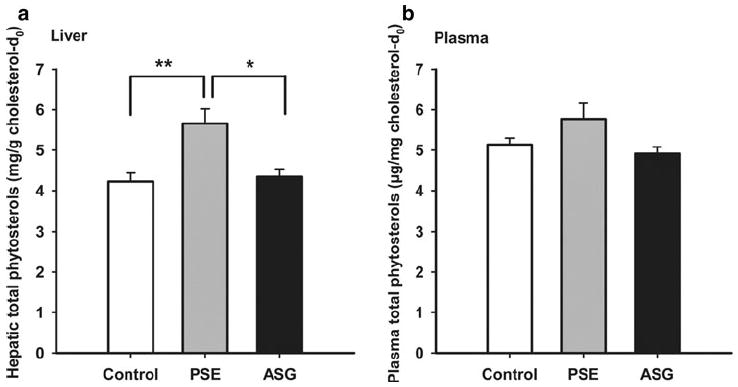

ASG administration was associated with less systemic absorption of total phytosterols than PSE (Fig. 4). Four hours after gavage, total liver phytosterols were increased 34.0 ± 8.5% (SEM) over control with PSE but only 2.7 ± 4.7% with ASG. Plasma phytosterol levels did not change significantly with either treatment.

Fig. 4.

Single-time-point study: total phytosterols in liver (a) and plasma (b). Mice (n = 5 for each group) were fasted for 2 h before gavage of purified soybean oil with cholesterol-d7 containing ASG (6.1 mg phytosterols), PSE (6.1 mg phytosterols), or no addition and were sacrificed 4 h later. Levels of total phytosterols in liver and plasma expressed relative to natural cholesterol were determined as described in the “Materials and Methods”. Values are means ± SE. Significance is indicated by *(P < 0.05) or **(P < 0.01)

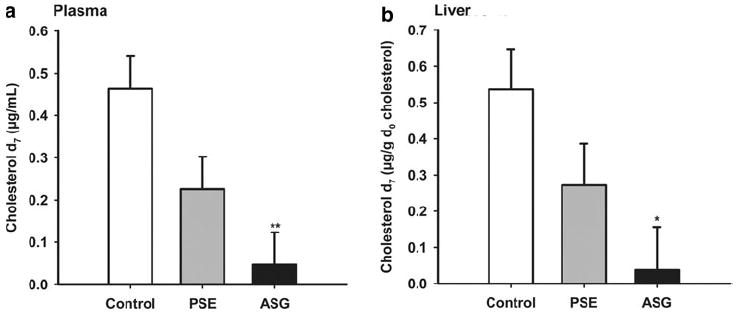

ASG had a large inhibitory effect on absorption of cholesterol-d7 into plasma and liver at 4 h (Fig. 5). Compared with control, ASG reduced plasma cholesterol-d7 by 90 ± 3.7% (SEM) and liver cholesterol-d7 by 86.2 ± 3.8%. Reductions by PSE of 51.4 ± 19.4% in plasma and 45.9 ± 25.7% in liver were more variable and not statistically significant.

Fig. 5.

Single-time-point study: cholesterol-d7 in plasma (a) and liver (b). Mice (n = 5 for each group) were fasted for 2 h before gavage of purified soybean oil with cholesterol-d7 containing ASG (6.1 mg phytosterols), PSE (6.1 mg phytosterols), or no addition. Mice were sacrificed 4 h later and levels of cholesterol d7 in plasma and liver were determined as described in “Materials and Methods”. Values are means ± SEM. Significance is indicated by **(P < 0.01)

Discussion

Extensive research has demonstrated that pure phytosterols, when properly formulated, reduce cholesterol absorption efficiency and plasma LDL cholesterol in animals and in humans. On the other hand, there is little published research on the physiological effects of phytosteryl glycosides. Recently we have demonstrated that ASG reduced cholesterol absorption efficiency in humans [19]. In the current study, ASG obtained from soybean-derived lecithin, was further purified and used to determine effects on cholesterol absorption and on uptake and cleavage of ASG in mouse intestine. Consistently, ASG reduced cholesterol absorption in vivo in mice, as observed in humans. ASG seemed to act locally in the gut lumen and mucosa with very little absorption into the systemic circulation. Furthermore, cleavage of glycosidic bonds was not required for biological activity of ASG. Most of the fatty acid moieties of ASG were removed, converting them to SG whereas the glycosidic bond remained intact.

Consistent with the known reduction in cholesterol absorption in humans, ASG reduced cholesterol absorption by 45% as determined by a three-day procedure when compared with the negative control (Fig. 1), indicating that ASG was bioactive in mice. PSE, the experimental positive control, reduced cholesterol absorption by 40% (Fig. 1). In a shorter time frame of 4 h, cholesterol d7, gavaged together with ASG in purified soybean oil, was subsequently found to be significantly reduced in liver and plasma compared with control (Fig. 5). These results show that ASG acts rapidly to reduce both the rate of cholesterol transport and the overall extent of cholesterol absorption.

Because standard rodent chow diets are rich in phytosterols, we used a novel cholesterol and phytosterol-free diet to enable better assessment of phytosterol absorption. Total phytosterols in the liver of mice given PSE were significantly higher than in those of control or ASG mice (Fig. 4a). In contrast, total phytosterols in the liver or plasma of mice gavaged with ASG were similar to those of the control (Fig. 4a, b), indicating that ASG was not absorbed into the systemic circulation. Our finding agrees with results from a study in which [4-14C]sitosteryl β-d-glucoside administered intragastrically to rats was not found after 3 h in liver, kidney, heart, lungs, spleen, muscle, brain, adipose tissue, or blood [21]. The same study fed unlabeled sitosteryl β-d-glucoside at 0.5 g/kg body weight to rats for four weeks and neither sitosteryl β-d-glucoside nor sitosterol or sitosteryl esters were found in significant amounts in tissues outside the alimentary canal during the entire feeding period. It is therefore unlikely that ASG enters the systemic circulation.

ASG seemed to act locally in the lumen or in the mucosa or both. After PSE treatment total phytosterols seemed to accumulate in the lumen across the quarters (Fig. 2a), consistent with the established mechanism of action of interfering with micellar cholesterol formation in the lumen. Total phytosterols in the mucosa from the PSE group increased rapidly from the second quarter onward, indicating uptake of phytosterols into mucosa and possible action of phytosterols inside the mucosa (Fig. 2b), albeit present at a much lower level compared with lumenal total phytosterols. After ASG treatment, total phytosterols in the mucosa increased from the second quarter onward (Fig. 2), similar to the pattern with PSE. Direct HPLC measurement confirmed that the accumulated phytosterols were in the form of ASG and SG (Fig. 3).

Our results strongly suggest that the bioactive components reducing cholesterol absorption are ASG or SG, but not the free phytosterols. Most of the phytosterol glycosides (92.5%) administered were in the form of ASG. Yet both ASG and SG were abundant in the lumen and mucosa in 4 h, indicating that ASG was hydrolyzed to SG in these locations. Consistent with the previous report that ASG was cleaved to SG in vitro by pancreatin and cholesterol esterase [20], most of the ASG was recovered as SG in stool samples three days after gavage, indicating that cleavage of ASG to SG was complete in three days. The complete recovery of ASG as fecal SG also indicates that SG were not hydrolyzed to free phytosterols. Furthermore, total phytosterol levels in the liver or plasma were similar to the respective levels in the control. This also is in agreement with the finding that only a small fraction of [4-14C]sitosteryl β-d-glucoside (<0.5%) was detected in the form of sitosterol and sitosteryl esters in the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and stomach [21]. Therefore, cleavage of the glycosidic bond seems to not be required for the biological activity of ASG in mice.

In summary, the results of this study have demonstrated that ASG is bioactive in mice. ASG was taken up rapidly into the mucosa 4 h after oral gavage. ASG was cleaved to SG so that most of the ASG given was present in the form of SG in the lumen and mucosa. ASG administered was recovered quantitatively from stool samples as SG. There was little systemic absorption of ASG into the plasma or liver and ASG/SG seemed to act locally in both the lumen and mucosa without being significantly absorbed into the systemic circulation. Bioactive in reducing cholesterol absorption in mice and humans, phytosteryl glycosides from either natural or synthetic sources could potentially be used for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Phytosteryl glycosides must be measured and taken into account when assessing the effects of phytosterols in the diet and for treatment of hypercholesterolemia.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 50420 and the Washington University Mass Spectrometry Resource (P41 RR00954). We appreciate Mrs. Robin Fitzgerald for her excellent technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ASG

Acylated steryl glycosides

- SG

Steryl glycosides

- PSE

Phytosteryl esters

- GC–MS

Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

Footnotes

Conflict of interest Dr. Ostlund and Washington University have a financial interest in Lifeline Technologies, a biotechnology company developing bioactive phytosterols. Lifeline products were not used in this study, and Lifeline and the authors have no financial interest in phytosteryl glycosides.

Contributor Information

Xiaobo Lin, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Lipid Research, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8127, 660 South Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

Lina Ma, Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Lipid Research, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8127, 660 South Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, USA.

Robert A. Moreau, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Eastern Regional Research Center, Wyndmoor, PA, USA

Richard E. Ostlund, Jr., Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism and Lipid Research, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, Campus Box 8127, 660 South Euclid Ave., St. Louis, MO 63110, USA Rostlund@dom.wustl.edu

References

- 1.Ostlund RE., Jr Phytosterols in human nutrition. Ann Rev Nutr. 2002;22:533–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.020702.075220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ostlund RE, Jr, Racette SB, Okeke A, Stenson WF. Phytosterols that are naturally present in commercial corn oil significantly reduce cholesterol absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(6):1000–1004. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostlund RE, Jr, Racette SB, Stenson WF. Inhibition of cholesterol absorption by phytosterol-replete wheat germ compared with phytosterol-depleted wheat germ. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77(6):1385–1389. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.6.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestel P, Cehun M, Pomeroy S, Abbey M, Weldon G. Cholesterol-lowering effects of plant sterol esters and non-esterified stanols in margarine, butter and low-fat foods. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55(12):1084–1090. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law MR. Plant sterol and stanol margarines and health. West J Med. 2000;173(1):43–47. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.173.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen TT. The cholesterol-lowering action of plant stanol esters. J Nutr. 1999;129(12):2109–2112. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.12.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronow WS. Cholesterol 2001. Rationale for lipid-lowering in older patients with or without CAD. Geriatrics. 2001;56(9):22–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Expert Panel on Detection. Executive summary of the third report of the national cholesterol education program (NCEP) Expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ostlund RE, Jr, Spilburg CA, Stenson WF. Sitostanol administered in lecithin micelles potently reduces cholesterol absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(5):826–831. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.5.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gremaud G, Dalan E, Piguet C, Baumgartner M, Ballabeni P, Decarli B, Leser ME, Berger A, Fay LB. Effects of non-esterified stanols in a liquid emulsion on cholesterol absorption and synthesis in hypercholesterolemic men. Eur J Nutr. 2002;41(2):54–60. doi: 10.1007/s003940200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spilburg CA, Goldberg AC, McGill JB, Stenson WF, Racette SB, Bateman J, McPherson TB, Ostlund RE., Jr Fat-free foods supplemented with soy stanol-lecithin powder reduce cholesterol absorption and LDL cholesterol. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(5):577–581. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katan MB, Grundy SM, Jones P, Law M, Miettinen T, Paoletti R. Efficacy and safety of plant stanols and sterols in the management of blood cholesterol levels. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(8):965–978. doi: 10.4065/78.8.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreau RA, Whitaker BD, Hicks KB. Phytosterols, phytostanols, and their conjugates in foods: structural diversity, quantitative analysis, and health-promoting uses. Prog Lipid Res. 2002;41(6):457–500. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(02)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Racette SB, Lin X, Lefevre M, Spearie CA, Most MM, Ma L, Ostlund RE., Jr Dose effects of dietary phytosterols on cholesterol metabolism: a controlled feeding study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(1):32–38. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin X, Racette SB, Lefevre M, Spearie CA, Most M, Ma L, Ostlund RE., Jr The effects of phytosterols present in natural food matrices on cholesterol metabolism and LDL-cholesterol: a controlled feeding trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64(12):1481–1487. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jonker D, van der Hoek GD, Glatz JFC, Homan C, Posthumus MA, Katan MB. Combined determination of free, esterified and glycosylated plant sterols in foods. Nutr Rep Int. 1985;32:943–951. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Normén L, Bryngelsson S, Johnsson M, Evheden J, Ellegard LBH, Brants H, Andersson H, Dutta P. The phytosterol content of some cereal foods commonly consumed in Sweden and in the Netherlands. J Food Comp Anal. 2002;15(6):693–704. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Normen L, Johnsson M, Andersson H, van Gameren Y, Dutta P. Plant sterols in vegetables and fruits commonly consumed in Sweden. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;38:84–89. doi: 10.1007/s003940050048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin X, Ma L, Racette SB, Anderson Spearie CL, Ostlund RE., Jr Phytosterol glycosides reduce cholesterol absorption in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296(4):G931–G935. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00001.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreau RA, Hicks KB. The in vitro hydrolysis of phytosterol conjugates in food matrices by mammalian digestive enzymes. Lipids. 2004;39(8):769–776. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1294-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber N. Metabolism of sitosteryl beta-d-glucoside and its nutritional effects in rats. Lipids. 1988;23(1):42–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02535303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin X, Ma L, Gopalan C, Ostlund RE. d-chiro-Inositol is absorbed but not synthesised in rodents. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(10):1426–1434. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509990456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37(8):911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ostlund RE, Jr, Hsu FF, Bosner MS, Stenson WF, Hachey DL. Quantification of cholesterol tracers by gas chromatography–negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 1996;31(11):1291–1296. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199611)31:11<1291::AID-JMS424>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Racette SB, Spearie CA, Phillips KM, Lin X, Ma L, Ostlund RE., Jr Phytosterol-deficient and high-phytosterol diets developed for controlled feeding studies. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:2043–2051. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostlund RE, Jr, McGill JB, Zeng CM, Covey DF, Stearns J, Stenson WF, Spilburg CA. Gastrointestinal absorption and plasma kinetics of soy Delta(5)-phytosterols and phytostanols in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;282(4):E911–E916. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00328.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreau RA, S KM, Haas MJ. The identification and quantification of steryl glucosides in precipitates from commercial biodiesel. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 2008;85:761–770. [Google Scholar]