Abstract

The 2001 expert consensus guidelines for treating major depressive disorder (MDD) in geriatric patients recommended antidepressant treatment in combination with psychotherapy. Recent evidence continues to support the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors as first-line agents in the elderly, and although the transdermal monoamine oxidase inhibitor selegilene has shown promise in adult patients, it has not been studied in geriatric depression. Augmentation therapy with atypical antipsychotics or other agents may provide benefits for agitated, psychotic, or resistant MDD in the elderly. The few treatment studies that have been conducted in the geriatric population since the publication of the guidelines have had mixed results and high placebo response rates. More large controlled trials are needed.

Drug Names: aripiprazole (Abilify); bupropion (Wellbutrin,Aplenzin,and others); citalopram (Celexa and others); clozapine (FazaClo,Clozaril,and others); duloxetine (Cymbalta); escitalopram (Lexapro and others); fluoxetine (Prozac and others); olanzapine, (Zyprexa); olanzapine-fluoxetine (Symbyax); paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others); selegiline (EMSAM); sertraline (Zoloft and others); venlafaxine (Effexor and others); ziprasidone (Geodon)

When the Expert Consensus Guidelines1 for the treatment of late-life depression were published in 2001, very few data were available to clinicians regarding effective treatments for older patients. Since that time, additional studies have been conducted and new treatments have become available, but the main recommendations of the guidelines are still valid. The consensus first-line treatment strategy in the guidelines for both mild and severe geriatric major depression was an antidepressant plus psychotherapy, and for psychotic major depression, an antidepressant plus an atypical antipsychotic. For an update on psychotherapy, please see “Psychotherapy for Late-Life Depression.”

Recent reviews2,3 of the literature have confirmed that antidepressants are more efficacious than placebo for late-life depression. In addition, evidence suggests that antidepressants may have a protective effect against suicide in those aged 65 years or older.4 However, additional studies on geriatric depression are needed, particularly in regard to treatment strategies for patients with treatment-resistant depression.

SSRIs

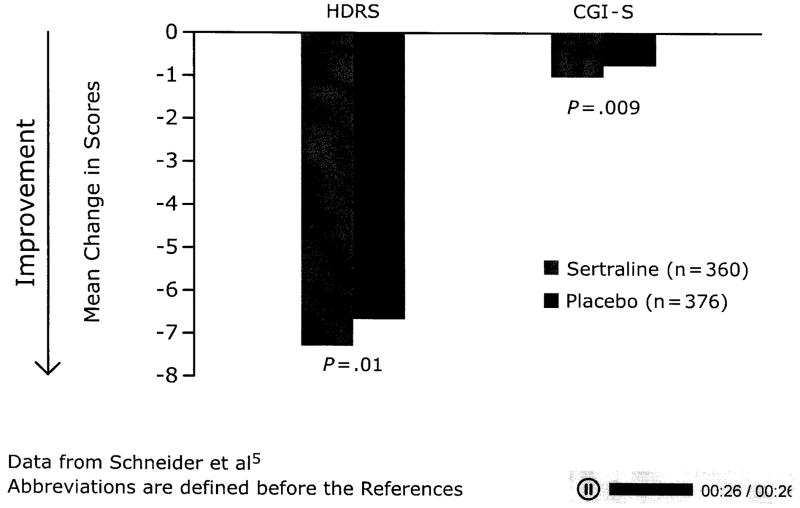

The antidepressants preferred by the experts1 for all types of depression were SSRIs, with sertraline and citalopram rated highest for efficacy and tolerability, followed by paroxetine, which was another first-line option. Studies published since the guidelines have had mixed results on the efficacy of these agents in older patients. Schneider et al5 found sertraline to be significantly more effective than placebo over an 8-week period, but the differences between placebo and sertraline were small (AV 1). The modest efficacy difference of this study may be related to the relatively low doses (50 or 100 mg/d) of sertraline as well as the high placebo response rate, which is common in studies of antidepressants in geriatric depression. Adverse events related to the treatment occurred in 8% of the sertraline group and 2% of the placebo group. Medical comorbidity, such as vascular disease, diabetes, or arthritis, does not seem to influence the efficacy of sertraline in geriatric depression.6

Although sertraline appears efficacious in treating acute depressive episodes in older patients, a maintenance study7 of sertraline found that continuing the drug for 2 years after remission did not appear to provide any more protection against recurrence than discontinuing it.

A study8 comparing the efficacy of citalopram with that of placebo in patients with unipolar depression who were aged 75 years and older suggested that citalopram was not superior to placebo in major depression except in moderately severe and severe cases. The possibility of high placebo response due to increased social interaction for the trial was cited. The newer agent escitalopram, the active isomer of citalopram, has been examined in older patients, but 2 studies9,10 found no difference from placebo in acute treatment. However, a 36-week relapse-prevention study11 in older patients who had achieved remission with escitalopram found escitalopram to be more effective than placebo. During the continuation phase, the recurrence rate with escitalopram was 9%, compared with 33% of patients who were switched to placebo following remission.

A 12-week, flexible-dose trial12 of paroxetine in older adults with MDD showed superiority of the drug over placebo. Remission was achieved by 43% of those taking paroxetine CR, 44% of those taking paroxetine IR, and 26% of those taking placebo. Discontinuation due to adverse events occurred in 13% of the paroxetine CR group, 16% of the paroxetine IR group, and 8% of the placebo group.

SNRIs

The experts also recommended the SNRI venlafaxine as first-line pharmacotherapy. Direct comparisons13–15 between venlafaxine and SSRIs so far have shown no differences in remission rates in the geriatric population. Further, the largest study13 (N = 300) found no difference in efficacy between venlafaxine IR, the SSRI fluoxetine, and placebo (although a significant reduction in HDRS scores from baseline to week 8 was reported in all 3 groups). One study16 comparing venlafaxine ER with a TCA found high remission rates with both medications, but no placebo group existed for comparison. Patients receiving venlafaxine experienced fewer side effects than patients receiving the TCA; however, venlafaxine appears to be less well tolerated than SSRIs.13,15

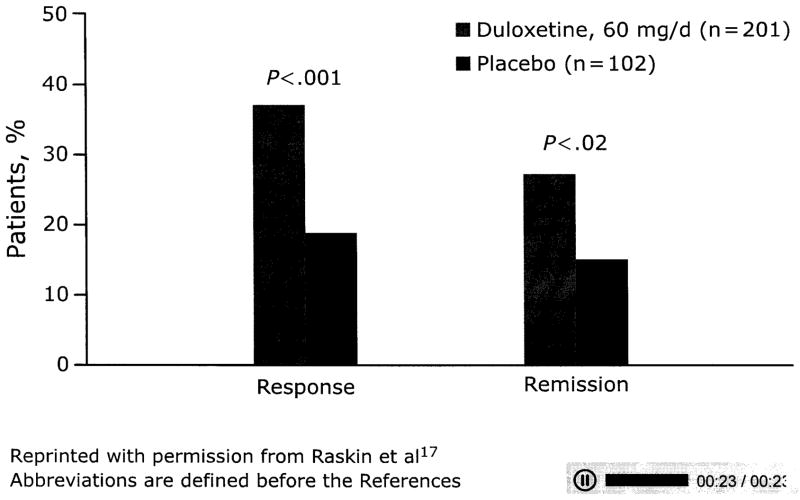

Since the publication of the guidelines, another SNRI, duloxetine, has shown good tolerability and significant improvement in depressive and pain symptoms versus placebo in older patients with MDD (AV 2).17 The efficacy and tolerability of duloxetine do not appear to be greatly affected by medical comorbidity.18 However, no large studies have examined the efficacy of duloxetine compared with SSRIs in treating late-life depression.

MAOIs

Studies19–21 have found adequate efficacy and tolerability of selegiline in acute and maintenance treatment of younger adult patients with MDD, but selegiline has not been studied in geriatric depression. Bodkin and Amsterdam21 found that 20 mg/d of selegiline applied via a transdermal patch produced greater improvement than placebo on all depression measures used. When delivered via transdermal patch, selegiline bypasses the liver, and, in small doses (6 mg/d), does not require a restricted diet.

Atypical Antipsychotics

Augmentation therapy of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotics in geriatric depression has still not been systematically investigated. The use of atypical antipsychotics has been associated with increased mortality in older patients with dementia,22 but illness and other medication factors may confound these findings.23 The mechanism by which atypical antipsychotic drugs might increase mortality in elderly patients with dementia is not well understood,24 and it is unclear whether the lower dosages used in augmentation therapy for geriatric depression will substantially increase mortality. The experts recommended caution when using atypical antipsychotic agents; for example, olanzapine and clozapine should be avoided in those who are obese or diabetic, and olanzapine and ziprasidone should be avoided in those with QTc prolongation or congestive heart failure.25 However, atypical antipsychotics likely increase appetite and weight and may be beneficial in elderly patients who are emaciated because of depression or anorexia related to depression and perhaps exacerbated by comorbid medical illnesses.

The olanzapine-fluoxetine combination has been shown to be efficacious for treatment-resistant depression26 and psychotic depression27 in adults, but this combination has not been studied in geriatric patients. However, a study28 of psychotic depression in both younger and older patients compared olanzapine plus sertraline with olanzapine plus placebo. Treatment with olanzapine/sertraline was associated with more patients achieving remission after 12 weeks (42%) than olanzapine/placebo (24%), and age did not affect efficacy results. Younger adults gained more weight than older patients and had greater increases in glucose, but all patients experienced increased cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

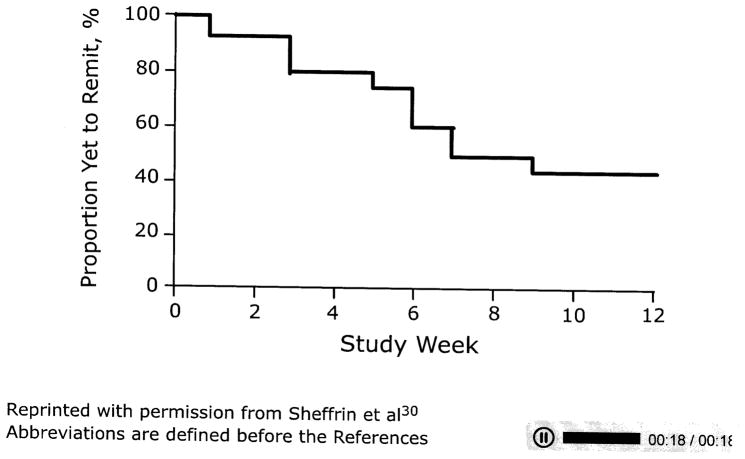

Placebo-controlled trials29 have demonstrated the efficacy of aripiprazole augmentation of antidepressants for adults with treatment-resistant depression. Although controlled trials with geriatric patients are lacking, a pilot study30 of aripiprazole augmentation over 16 weeks in 24 geriatric patients who had not achieved full remission with sequential SSRI and SNRI treatment found that aripiprazole was well tolerated (AV 3).

Bupropion and Triiodothyronine

The STAR*D study,31 which had a relatively small older population, found that bupropion and triiodothyronine were effective as augmentation to antidepressants in treatment-resistant MDD. Studies of this kind specifically for geriatric psychiatry are needed to provide a variety of augmentation therapies for this population.

Conclusion

Few studies of geriatric depression have been conducted since the 2001 publication of the treatment guidelines1. The findings on SSRIs and SNRIs still support their use as first-line agents, and the MAOI selegiline merits more study in the geriatric population. The high placebo response seen in geriatric studies may in part be explained by the social support and other nonspecific therapeutic factors offered by the study staff to depressed, socially Isolated elderly patients. Augmenting agents such as atypical antipsychotics, bupropion, and triiodothyronine may be beneficial in treating geriatric depression, but additional studies are needed.

Figure 1.

AV 1. Mean Change in Scores For Elderly Patients With MDD Treated With Sertraline Vs Placebo

Data from Schneider et al5

Abbreviations are defined before the References

Figure 2.

AV 2. Response and Remission Rates for Geriatric Patients With MDD Receiving Duloxetine Vs Placebo

Reprinted with permission from Raskin et al17

Abbreviations are defined before the References

Figure 3.

AV 3. Time to Remission in Elderly Patients With Resistant MDD Treated With Aripiprazole Augmentation to an SNRI

Reprinted with permission from Sheffrin et al30

Abbreviations are defined before the References

For Clinical Use.

Combining psychotherapy and antidepressants to treat both mild and severe geriatric depression continues to be first-line treatment

An antidepressant plus an atypical antipsychotic is the first-line recommendation for geriatric psychotic depression

Additional studies are needed in the elderly population to determine safe and efficacious pharmacotherapeutic strategies for depression

Acknowledgments

Supported by an educational grant from Eli Lilly and Company.

Abbreviations

- CGI-S

Clinical Global Impressions-Severity

- CR

controlled release

- ER

extended release

- HDRS

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- IR

Immediate release

- MAOI

monoamine oxidase inhibitors

- MDD

major depressive disorder

- SNRI

serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor

- SSRI

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

- STAR*D

Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression

- TCA

tricyclic antidepressant

References

- 1.Alexopoulos GS, Katz IR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. for the Expert Consensus Panel for Pharmacotherapy of Depressive Disorders in Older Patients. The expert consensus guideline series: pharmacotherapy of depressive disorders in older patients. Postgrad Med. 2001;(Spec No):1–86. Pharmacotherapy. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajji TK, Mulsant BH, Lotrich FE, et al. Use of antidepressants in late-life depression. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(10):841–853. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200825100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roose SP, Schatzberg AF. The efficacy of antidepressants in the treatment of late-life depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(4 suppl 1):S1–S7. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000162807.84570.6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, et al. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2880. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneider LS, Nelson JC, Clary CM, et al. An 8-week multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of sertraline in elderly outpatients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(7):1277–1285. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.7.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheikh JI, Cassidy EL, Doraiswamy PM, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of sertraline in patients with late-life depression and comorbid medical illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):86–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson KC, Mottram PG, Ashworth L, et al. Older community residents with depression: long-term treatment with sertraline, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182(6):492–497. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.6.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roose SP, Sackeim HA, Krishnan KR, et al. Antidepressant pharmacotherapy in the treatment of depression in the very old: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):2050–2059. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bose A, Li D, Gandhi C. Escitalopram in the acute treatment of depressed patients aged 60 years or older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181591c09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasper S, de Swart H, Friis Andersen H. Escitalopram in the treatment of depressed elderly patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(10):884–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.10.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorwood P, Weiller E, Lemming O, et al. Escitalopram prevents relapse in older patients with major depressive disorder. Am J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;15(7):581–593. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000240823.94522.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rapaport MH, Schnelder LS, Dunner DL, et al. Efficacy of controlled-release paroxetine in the treatment of late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(9):1065–1074. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schatzberg A, Roose S. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of venlafaxine and fluoxetine in geriatric outpatients with major depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(4):361–370. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000194645.70869.3b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allard P, Gram L, Timdahl K, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine in geriatric outpatients with major depression: a double-blind, randomised 6-month comparative trial with citalopram. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(12):1123–1130. doi: 10.1002/gps.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oslin DW, Ten Have TR, Streim JE, et al. Probing the safety of medications in the frail elderly: evidence from a randomized clinical trial of sertraline and venlafaxine in depressed nursing home residents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(8):875–882. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gasto C, Navarro VMT, et al. Single-blind comparison of venlafaxine and nortriptyline in elderly major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200302000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Sheikh J, et al. Efficacy of duloxetine on cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major depressive disorder: an 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):900–909. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wise TN, Wiltse CG, Iosifescu DV, et al. The safety and tolerability of duloxetine in depressed elderly patients with and without medical comorbidity. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(8):1283–1293. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amsterdam JD. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the safety and efficacy of selegiline transdermal system without dietary restrictions in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(2):208–214. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amsterdam JD, Bodkin JA. Selegiline transdermal system in the prevention of relapse of major depressive disorder: a 52-week, double-blind, placebo-substituteion, parallel-group clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):579–586. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000239794.37073.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodkin JA, Amsterdam JD. Transdermal selegiline in major depression: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study in outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1869–1875. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeste DV, Blazer D, Casey D, et al. ACNP White Paper: update on use of antipsychotic drugs in elderly persons with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(5):957–970. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simoni-Wastila L, Ryder PT, Qian J, et al. Association of antipsychotic use with hospital events and mortality among medicare beneficiaries residing in long-term facilities. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(5):417–427. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31819b8936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kales JC, Valenstein M, Kim HM, et al. Mortality risk in patients with dementia treated with antipsychotics versus other psychiatric medications. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1568–1576. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexopoulos GS, Streim J, Carpenter D, et al. Using antipsychotic agents in older patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 2):5–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dodd S, Berk M. Olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy and clinical utility. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(9):1299–1306. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.9.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothschild AJ, Williamson DJ, Tohen MF, et al. A double-blind, randomized study of olanzapine and olanzapine/fluoxetine combination for major depression with psychotic features. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):365–373. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130557.08996.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyers BS, Flint AJ, Mulsant BH, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of olanzapine plus sertraline vs olanzapine plus placebo for psychotic depression: the study of pharmacotherapy of psychotic depression (STOP-PD) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):838–847. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berman RM, Fava M, Thase ME, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in major depressive disorder: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with inadequate response to antidepressants. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(4):197–206. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheffrin M, Driscoll HC, Lenze EJ, et al. Pilot study of augmentation with aripiprazole for incomplete response in late-life depression: getting to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(2):208–213. doi: 10.4088/jcp.07m03805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rush AJ, Warden D, Wisniewski SR, et al. STAR*D: revising conventional wisdom. CNS Drugs. 2009;23(8):627–647. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923080-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]