Abstract

Even students who reject evolution are often willing to consider cases in which evolutionary biology contributes to, or undermines, biomedical interventions. Moreover the intersection of evolutionary biology and biomedicine is fascinating in its own right. This review offers an overview of the ways in which evolution has impacted the design and deployment of live-attenuated virus vaccines, with subsections that may be useful as lecture material or as the basis for case studies in classes at a variety of levels. Live- attenuated virus vaccines have been modified in ways that restrain their replication in a host, so that infection (vaccination) produces immunity but not disease. Applied evolution, in the form of serial passage in novel host cells, is a “classical” method to generate live-attenuated viruses. However many live-attenuated vaccines exhibit reversion to virulence through back-mutation of attenuating mutations, compensatory mutations elsewhere in the genome, recombination or reassortment, or changes in quasispecies diversity. Additionally the combination of multiple live-attenuated strains may result in competition or facilitation between individual vaccine viruses, resulting in undesirable increases in virulence or decreases in immunogenicity. Genetic engineering informed by evolutionary thinking has led to a number of novel approaches to generate live-attenuated virus vaccines that contain substantial safeguards against reversion to virulence and that ameliorate interference among multiple vaccine strains. Finally, vaccines have the potential to shape the evolution of their wild type counterparts in counter-productive ways; at the extreme vaccine-driven eradication of a virus may create an empty niche that promotes the emergence of new viral pathogens.

Keywords: live-attenuated, vaccine, virus, biomedicine, evolution, adaptation, reversion to virulence

Overview

Even students who balk at the very mention of the word evolution can often be persuaded to consider examples of microbial evolution, and thus to become familiar with the processes common to all biological evolution. Having experienced the inescapable logic of the theory of evolution through these “non-threatening” examples, such skittish students are sometimes then willing to accept the role of evolution in the diversification of other forms of life. Students are often especially receptive to learning how evolution can be used generate beneficial organisms for biomedicine and biotechnology, a subset of the more general category of “applied evolution” [1], as well how evolution can sabotage biomedical interventions (e.g. evolution of antibiotic resistance, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/library/10/4/l_104_03.html).

In the following review I focus on the role of evolution in the successes and failures of one such intervention: live-attenuated virus vaccines. These vaccines are live viruses that have been modified in ways that restrain their replication in a host, so that infection (vaccination) produces immunity but not disease [2]. Thus killed and protein subunit vaccines are excluded from consideration, as are vectored vaccines in which an immunogenic protein from one virus is inserted into another species of virus [3, 4]. Many of the vaccines currently licensed for use in humans, including the Sabin oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), the combined measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, and the chickenpox (varicella virus) vaccine, are composed of live-attenuated viruses (Table 1). These vaccines have been a tremendous boon to human health (e.g. [5-8] but see [9] for some of the failures and inequities in vaccine deployment). To list just a few examples, variola virus, the agent of smallpox, has been eradicated from the world, poliovirus is approaching global eradication [10], measles virus has been eliminated from the United States [6] (but see [11]), and the incidence of chickenpox has dropped dramatically in the U.S. [12]. However live-attenuated vaccines are not without their risks, which derive primarily from the further evolution of vaccine viruses themselves as well as the impact of vaccine-driven immunity on the evolution of their wild-type counterparts.

Table 1.

Live-attenuated virus vaccines currently licensed for use in the United States (www.fda.gov)

| Live-attenuated virus(es) | Trade Name |

|---|---|

| Adenovirus Types 1 and 4 | None |

| Influenza | Flumist |

| Measles | Attenuvax |

| Measles and Mumps | M-M-Vax |

| Measles, Mumps and Rubella | M-M-R II |

| Measles, Mumps, Rubella and Varicella | Pro-Quad |

| Mumps | Mumpsvax |

| Rotavirus | ROTARIX |

| Rotavirus | RotaTeq |

| Rubella | Meruvax II |

| Vaccinia | ACAM2000 |

| Varicella | Varivax |

| Yellow Fever | YF-Vax |

| Zoster (Varicella) | Zostavax |

My intention here is to explore both the positive and negative impacts of evolution on the success of live-attenuated virus vaccines and thereby provide cases of microbial evolution with great relevance to human health. I have used many of the subsections below, modified to incorporate appropriate levels of detail, in a wide variety of college classes ranging from Introductory Biology for Non-Majors through to Advanced Virology. Students have found them useful and interesting in their own right and I have often used them as an entrée to a more general overview of evolutionary theory.

Applied evolution: generating live-attenuated vaccines by serial passage

To date, all live virus vaccines licensed for use in humans in the United States (Table 1) have been generated by one of two “classical” approaches: (i) the Jennerian approach, first utilized by Edward Jenner, in which a related virus from a non-human animal is used to protect against a human virus or (ii) the Pastorian approach, first employed by Louis Pasteur, of serial passage (Figure 1A) [13]. Both methods leverage the evolutionary principle that fitness is always specific to a particular environment, and thus high fitness in one environment may come at a cost of low fitness in another.

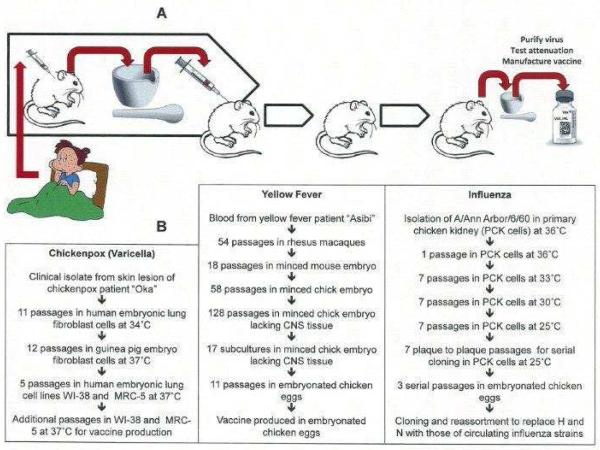

Figure 1.

A) The Pastorian approach for attenuation by serial passage. B) Passage history of three live-attenuated virus vaccines derived by serial passage: the yellow fever virus 17D vaccine strain [40], the cold-adapted influenza A/Ann Arbor/6/60 vaccine strain [16], and the chickenpox (varicella) Oka vaccine strain [12, 86].

In serial passage, adaptations that enhance replication of a virus in a novel host or environmental condition may lead to attenuated replication in the natural host or condition. Adaptation is accomplished by infecting a live animal or a flask of cultured cells with a wild type virus, allowing the virus to replicate until it reaches a useful concentration, harvesting the virus, and then using these progeny virions to initiate another infection in a new animal or culture (Figure 1A). Pasteur was the first to use this technique, passaging rabies virus in rabbits in order to attenuate it for dogs and humans [14]. Most subsequent live-attenuated viruses have also been generated by passage through a novel host or hosts. The vaccine for yellow fever virus, a pathogen that is maintained in African and South American primates under natural conditions, was created via passage through Asian macaques, mouse embryo tissues and chick embryo tissues (Figure 1B). The vaccine for measles virus, which in nature exclusively infects humans, was generated by passage through chick embryo cells [15], and the vaccine for varicella, another virus that infects only humans during natural transmission, was achieved through passage in guinea pig cells (Figure 1B). Additionally, adaptation to replication at lower temperatures is often a desirable evolutionary outcome. The cold-adapted influenza virus was passaged in chicken kidney cells in temperatures descending from 36° C to 25° C (Figure 1B), with the goal of generating a virus that could replicate in the upper respiratory tract but not deeper in the lungs [16].

Because evolution relies on the random occurrence and subsequent spread of rare beneficial mutations, the number of passages and the number of conditions needed to achieve satisfactory attenuation varies considerably (Figure 1B). For example the varicella vaccine virus was generated by just 28 passages in three different cell lines, while the yellow fever vaccine required hundreds of passages in five different conditions (Figure 1B). At first blush it may seem startling that viruses can undergo substantial evolution in just ten or twenty passages. However viral evolution is known to proceed at a breakneck pace due to the unique features of viral genetics and viral population dynamics [17, 18].

Viruses have genomes composed of RNA or DNA. Due to the lack of proofreading in RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, RNA viruses have extraordinarily high rates of mutation. The average RNA virus genome experiences one mutation per ten thousand nucleotides per replication, a rate of mutation almost a million times faster than the average bacterial genome [19]. Additionally RNA genomes tend to be very small, 10 kilobases (kb) or less [17], and thus on average RNA genomes accumulate approximately one mutation per genome per replication. The rate of mutation in RNA genomes is so high that RNA viruses may exist as a quasispecies, a swarm of related genetic variants whose interactions determine attributes of the population [20]. DNA viruses show a much greater range in genome size, from 3.2 kb (hepatitis B virus [21]) to 1.2 megabases (mimivirus [22]). Intriguingly, the rate of mutation in DNA viruses shows an inverse correlation with genome size, and small single-stranded DNA genomes may mutate at a rate comparable to RNA genomes [19, 23]. The pace of adaptation depends not only on genomic mutation rate but also on the rate of replication and final population size of those genomes [17]. Most viruses replicate rapidly within their hosts and some can achieve quite staggering population sizes: for example three days after an infectious mosquito bite West Nile virus reaches titers greater than 1011 plaque-forming units per ml of serum in certain bird hosts [24], a number that greatly exceeds the six billion humans currently alive and that is roughly equivalent to the number of stars in the Milky Way. Thus viruses easily outstrip the evolutionary pace of any other living organism, and this allows the evolution of live-attenuated vaccines over a relatively small number of serial passages.

Vaccines gone wild: Reversion to virulence in live-attenuated vaccines

In the classical methods of attenuation, a vaccine virus’s phenotype determines its genotype. Passage proceeds until satisfactory attenuation is achieved, irrespective of how many passages or how many mutations this may entail. Indeed, with the notable exception of the OPV polio vaccine strains [25], the mutations responsible for the attenuation of most live-attenuated vaccines have not been fully characterized. However it is clear that in some live-attenuated viruses, the number of attenuating mutations is quite small. Each of the attenuated poliovirus types 1, 2 and 3 strains in OPV carries only a few (two to six) major attenuating mutations [25]. Given the rapid mutation rates of all viruses, but particularly RNA viruses, it is not surprising that some vaccine viruses revert to virulence. About one in every 750,000 children receiving the first dose of OPV experiences vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis attributable to reversion of one of the three strains [25]. This propensity to revert is one of the reasons that OPV was replaced with the inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) in the United States, hence OPV is not listed in Table 1. Such reversion may occur as a result of back-mutation of attenuating mutations, compensatory mutations elsewhere in the genome, or, as discussed in the next section, recombination. Conversely, the more attenuating mutations in the genome of a live-attenuated vaccine, the less likely reversion will be. To date, the cold-adapted influenza vaccine, with attenuating mutations in four of the eight genome segments [16], has never reverted to virulence in a vaccinee [26].

Recently, quasispecies heterogeneity per se has also been implicated in changes in virulence [27, 28]. Sauder et al. [28] passaged mumps vaccine virus in either monkey kidney or chicken embryo fibroblast cells. They found that these passaged strains showed additional attenuation in rats and that this phenotypic change was associated with changes in quasispecies heterogeneity rather than fixation of any individual mutation.

Several factors can increase the likelihood that a live-attenuated vaccine will revert to virulence. First, the loss of a subset of attenuating mutations during vaccine manufacture can accelerate reversion. Often the cell lines approved for vaccine manufacture differ from the cell lines in which the serial passage of the vaccine was conducted, thus changing the selection pressures on the virus. Complete reversion to virulence would be detected during safety testing and such lots would be eliminated, but if attenuation is enacted by the epistatic effect of multiple mutations [29], and a subset of these are lost during vaccine manufacture, then complete reversion would require fewer subsequent mutations. A recent study by Victoria et al. [30] searched for back-mutation of attenuating mutations in lots of eight live-attenuated virus vaccines strains, including OPV, using deep sequencing, and found none. However previous studies of the OPV have detected variants lacking particular attenuating mutations in vaccine lots [25].

Second, reversion is more likely the longer vaccine virus replication persists and the higher the virus titer achieved in an individual vaccinee. Extended replication offers more mutational fodder and more time for natural selection to occur within an environment (the host). Such selection is likely to favor virus variants that replicate to higher titers or in a greater range of tissue types than the original vaccine virus, i.e. viruses that are more similar to the wild-type phenotype. Both overall levels of replication and breadth of tissue tropism may be positively correlated with virulence. Valsamakis et al. [31] experimentally passaged a measles vaccine virus in human tissues engrafted into mice and observed reversion to virulence. Moreover OPV has been shown to replicate to high titers over long periods of time in some immunodeficient vaccinees, resulting in reversion to virulence [25, 32]. These immunodeficient individuals also excrete polioviruses over long periods of time, increasing the likelihood of fecal-oral transmission to unvaccinated individuals in the community.

Such transmission from vaccinees to unvaccinated individuals is a third contributor to reversion to virulence. Although live-attenuated vaccine transmission was initially considered a bonus of live vaccines, a “free” vaccination, it is now clear that person-to-person transmission imposes strong selection for a return to the wild-type phenotype. Recognizing this, polio researchers divide vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) isolates into three categories: (i) iVDPVs derived from immunodeficient patients, (ii) cVDVPs that show evidence of sustained person-to-person transmission, and (iii) aVDPVs from non-immunodeficient patients or environmental sources that are not associated with an outbreak [25]. Predictably, virulent vaccine-derived viruses have caused substantial outbreaks in countries where so few children are vaccinated with OPV that herd immunity, the protection of susceptible individuals that occurs when pathogen transmission is “short-circuited” by vaccinated individuals [33], is never generated [25]. Surprisingly, virulent revertants, presumably derived from long-term OPV excretors or from contact with individuals from countries that continue to use OPV, are also detected in wastewater in countries where only the inactivated poliovirus vaccines is utilized [34, 35], suggesting that cessation of vaccination could result in re-emergence of virulent poliovirus in these regions.

OPV is affordable and vaccination prevents not only polio disease but also poliovirus transmission, making it an excellent vaccine for the eradication of poliovirus. However its tendency to slip the leash of attenuation and spawn virulent, vaccine-derived polioviruses through back-mutation as well as recombination (discussed below) has led to the “oral polio vaccine paradox” [36]: the same agent that eradicates a disease may serve to re-introduce it! One solution to this paradox is a concurrent, worldwide conversion to inactivated polio vaccine [36, 37], which would require an unprecedented feat of global coordination.

Hopeful monsters: Recombination among live-attenuated vaccine strains and between vaccine and other circulating viruses

In several licensed (Table 1) and candidate [4] live virus vaccines, multiple strains of a single species or multiple species are administered concurrently. Moreover vaccine viruses may be administered simultaneously with a natural infection of a conspecific or heterospecific virus. Both situations create potential for recombination between viral genomes. Virus genomes recombine by one of three general mechanisms: (i) break and repair in DNA genomes, (ii) polymerase template switching in RNA genomes, and (iii) reassortment of segments in segmented RNA genomes [38]. All three mechanisms require co-infection of a single cell by two different parental genotypes. Because many vaccine viruses undergo limited replication relative to wild type viruses, e.g. [12, 39-43], it would initially seem unlikely that more than one virion would enter a given cell. Moreover viruses possess a diverse array of mechanisms to prevent additional viruses from entering an infected cell, a process known as superinfection exclusion ([44] and references therein). However it is increasingly clear that, for some viruses, co-infection occurs at rates greater than expected by chance when viral density is very low. Such coinfection enhancement suggests either that a small fraction of appropriate host cells are actually susceptible to infection [45-47] or that viruses may possess mechanisms to enhance coinfection at low viral densities [48].

Recombination contributes to the reversion to virulence and subsequent circulation of OPV strains. Such recombination can occur between vaccine viruses, between vaccine and wild type polioviruses, and between vaccine polioviruses and other species of enteroviruses [25]. Recombination can occur at multiple locations in the genome, and multiple recombination events can contribute to the formation of a single genome. An extreme example of this process is a penta-recombinant VDPV, showing five crossover sites between type 2 polio and type 3 polio vaccine strains, that was isolated from a child suffering from poliomyelitis [49]. Recombination between vaccine and wild type viruses has also been documented for numerous virus vaccines for veterinary pathogens, including canine parvovirus [50], infectious bursal disease virus [51], bovine herpesvirus 1 [52], and infectious bronchitis virus [53]. Recombination is troubling not only for its contribution to virulence, but also because of its potential to generate entirely new species of viruses—western equine encephalitis virus, for example, is the product of recombination between eastern equine encephalitis virus and a Sindbis-like virus [54, 55].

Too much of a good thing: competition and facilitation among strains in multi-strain vaccines

Vaccine viruses can exhibit quite different dynamics when administered in combination with other vaccine viruses than when administered alone. At one end of the spectrum, the individual components of a multi-strain vaccine can show “interference”, in which one or more strains replicate to lower levels or stimulate a poorer immune response in a combined vaccine than a single-strain vaccine. Interference can be the product of immunodominance, direct competition for cellular or viral replication machinery, or immune-mediated apparent competition. Such interference has long been recognized; Sabin and his colleagues [56] pointed out in 1960 that the individual components of OPV were more efficacious when administered individually (as monovalent vaccines) than when administered together in a trivalent vaccine. Subsequently, multiple instances of interference among live-attenuated vaccine viruses have been documented ([57] and references therein). At the other end of the spectrum, facilitation, in which the replication or immunogenicity of attenuated viruses is enhanced in combination, could also occur. While this phenomenon has not been documented in vaccine viruses to the best of my knowledge, previous studies have certainly shown facilitation between unrelated viruses during concurrent infection [46, 58-60], thus a similar interaction between vaccine viruses is possible. While the outcome of interference and facilitation have been described, the mechanisms driving these dynamics are poorly understood. However as the number of new live-attenuated vaccines targeted to the already overscheduled child continues to increase, it is becoming increasingly important to gain a mechanistic understanding of the ecological interactions among these attenuated viruses.

Lessons learned: Evolutionary considerations in the rational design of live attenuated vaccines

Reverse genetics has offered a new approach for the generation of vaccines, namely rational vaccine design. In this approach, genotype determines virus phenotype. Potentially attenuating mutations are chosen based on available knowledge of the molecular biology of the virus. These mutations are engineered into a recombinant genome that is inserted into a cell, where it generates a recombinant virus. The attenuation of the resulting virus is assessed in a relevant model, and if it is either over- or under-attenuated then the mutation may be modified or additional mutations may be added.

While rational vaccine design is not a case of applied evolution, to be successful it must be informed by evolutionary thinking. In particular, due consideration must be given to preventing reversion to virulence. This may be ensured by the generation of large mutations (particularly deletions), numerous mutations with epistatic interactions, or chimeric viruses in which the structural proteins of a well-attenuated virus are replaced with those of the virus targeted for immunization. These strategies have been employed in the generation of candidate vaccines for dengue [4] and chikungunya viruses [27]. Alternatively, virus genes responsible for counteracting host antiviral responses may be deleted [61] or genes in the genome may be rearranged to de-optimize translation and genome synthesis [62]. As an additional safeguard against reversion, mutations that specifically prevent transmission may also be sought, e.g. [61, 63]. Rational vaccine design may also minimize competition among multiple strains of the same virus (multivalent vaccines) by introducing the same mutation into each of the strains, as has been done with candidate vaccines containing all four serotypes of dengue virus [64]. In addition, evolutionary thinking has led to novel approaches to enacting attenuation. As one example, Vignuzzi et al. [65], reasoning that quasispecies diversity enhances RNA virus fitness, have generated polioviruses in which the fidelity of the polymerase is significantly enhanced. Not only are such viruses attenuated, but, because their rate of mutation is lower, they are less able to revert to a less faithful polymerase. In another example, researchers have taken advantage of the tendency of viruses to exhibit codon pair bias: within all of the options in the degenerate genetic code viruses tend to use a subset of pairs of codons to encode specific pairs of amino acids. De-optimizing these codon pairs by inserting different codons that retain the original amino acid sequence results in attenuated influenza [66] and polioviruses [67]. This strategy involves hundreds of mutations across the genome and has been called, poetically, “death by a thousand cuts” [67]. Clearly it will stand as a significant barrier to reversion to virulence. Thus evolutionary thinking is leading to entirely new ways to engineer viral genomes to achieve attenuation.

Under pressure: How selection by vaccine-generated immunity can shape evolution of wild-type viruses

Viruses evolve in response to natural herd immunity, and it stands to reason that sufficiently high levels of vaccine-induced immunity could also shape virus evolution [68]. Evolution of wild type viruses in response to deployment of live-attenuated vaccines has been observed in several veterinary viruses, including avian metapneumovirus [69, 70] and avian influenza virus [71, 72]. The effects of such vaccine-driven evolution on virus virulence and transmissibility in unvaccinated animals have yet to be determined. However theoretical studies have raised the concern that “imperfect vaccines”, vaccines that do not induce sterilizing immunity but rather modulate disease or transmission, could select for increasing virulence in the wild type virus targeted by vaccination [73-78]. Intriguingly, Manuel et al. [79] recently reported that imperfect vaccination can prevent reversion to virulence in a simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV). They generated a SHIV carrying an attenuating mutation and then infected both naïve and vaccinated monkeys with this virus. The attenuated SHIV reverted to virulence through back-mutation in the naïve, but not the vaccinated, monkeys. The investigators attribute this effect to the overall decrease in SHIV replication in the vaccinated monkeys, suggesting that imperfect vaccines may act as a brake on the evolution of their wild-type counterparts.

The ultimate goal of many vaccination programs is the eradication of specific wild type viruses. This goal has been achieved for variola virus, the agent of smallpox, is within reach for poliovirus [25] and perhaps measles virus [80, 81], and remains a tempting target for many existing and candidate vaccine programs. While there is no question that eradication represents a quantum leap for public health, some thought must be given to the empty niche that eradication creates. Recent increases in monkeypox have been attributed to the eradication of, and cessation of vaccination against, smallpox [82]. Moreover, Coxsackie A virus [83] and sylvatic dengue virus [84] could potentially emerge to fill the niches left vacant should polio and human dengue virus, respectively, be eradicated. Evolutionary analysis will be needed to predict the impacts of eradication on future viral emergence.

Conclusion

In 1937, Max Theiler, the father of the yellow fever vaccine, wrote “One of the most striking phenomena to the student of virus diseases is the occurrence of variants.” [85]. Of course evolutionary biologists are equally fascinated by variants, and it is my hope that this review has shown how evolutionary biology and vaccinology have been intertwined since the inception of vaccination and how they must remain linked for vaccine design and deployment to proceed safely and effectively. The information and references herein may be useful for design of lectures or introduction to case studies that demonstrate the contributions of evolutionary biology to biomedical advances, including the generation of most of the virus vaccines in use today and creation of novel strategies for vaccine design. This review can also be used to emphasize the danger of ignoring evolution when deploying live-attenuated vaccine viruses, as, without due safeguards, evolution may reshape the virulence or transmissibility of these agents. Moreover virus vaccines themselves can and have influenced the evolution of naturally occurring viruses; the consequences of vaccination as a force of selection will continue to unfold as new vaccines are created and old vaccines become available to a larger proportion of the global population.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a Woods Hole Marine Biology Laboratory Karush scholarship and NIH 2P20RR016840-09. Special thanks to Dr. Stephen Whitehead (NIAID) for assistance with Figure 1 and to Dr. Timothy Wright (NMSU) and two anonymous reviewers for useful critique of the draft manuscript.

References

- 1.Bull JJ, Wichman HA. Applied Evolution. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 2001;32:183–217. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moser M, Leo O. Key concepts in immunology. Vaccine. 2010;28(Suppl 3):C2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Girard MP, Osmanov SK, Kieny MP. A review of vaccine research and development: the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Vaccine. 2006;24(19):4062–4081. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durbin AP, Whitehead SS. Dengue vaccine candidates in development. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;338:129–143. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-02215-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Widdowson MA, Steele D, Vojdani J, Wecker J, Parashar U. Global rotavirus surveillance: determining the need and measuring the impact of rotavirus vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(Suppl 1):S1–8. doi: 10.1086/605061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roush SW, Murphy TV. Historical comparisons of morbidity and mortality for vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2155–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou F, Santoli J, Messonnier ML, Yusuf HR, Shefer A, Chu SY, Rodewald L, Harpaz R. Economic evaluation of the 7-vaccine routine childhood immunization schedule in the United States, 2001. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1136–1144. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.12.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Levine MM, Robins-Browne R. Vaccines, global health and social equity. Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87(4):274–278. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francis DP. Successes and failures: Worldwide vaccine development and application. Biologicals. 2010;38(5):523–528. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nathanson N, Kew OM. From emergence to eradication: the epidemiology of poliomyelitis deconstructed. Am J Epidemiol. 172(11):1213–1229. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Measles --- United States, january--may 20, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(20):666–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hambleton S, Gershon AA. Preventing varicella-zoster disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(1):70–80. doi: 10.1128/CMR.18.1.70-80.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bazin H. A brief history of the prevention of infectious diseases by immunisations. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;26(5-6):293–308. doi: 10.1016/S0147-9571(03)00016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plotkin SA, editor. History of Vaccine Development. Springer; New York: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Live attenuated measles vaccine. EPI Newsl. 1980;2(1):6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maassab HF, DeBorde DC. Development and characterization of cold-adapted viruses for use as live virus vaccines. Vaccine. 1985;3(5):355–369. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(85)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moya A, Holmes EC, Gonzalez-Candelas F. The population genetics and evolutionary epidemiology of RNA viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2(4):279–288. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Domingo E, Parrish CR, Holland J, editors. Origin and Evolution of Viruses. Second Edition edn Academic Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanjuan R, Nebot MR, Chirico N, Mansky LM, Belshaw R. Viral mutation rates. J Virol. 2010;84(19):9733–9748. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00694-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauring AS, Andino R. Quasispecies theory and the behavior of RNA viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(7):e1001005. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liang TJ. Hepatitis B: the virus and disease. Hepatology. 2009;49(5 Suppl):S13–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.22881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Claverie JM, Abergel C, Ogata H. Mimivirus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;328:89–121. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-68618-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duffy S, Shackelton LA, Holmes EC. Rates of evolutionary change in viruses: patterns and determinants. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9(4):267–276. doi: 10.1038/nrg2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komar N, Langevin S, Hinten S, Nemeth N, Edwards E, Hettler D, Davis B, Bowen R, Bunning M. Experimental infection of North American birds with the New York 1999 strain of West Nile virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9(3):311–322. doi: 10.3201/eid0903.020628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kew OM, Sutter RW, de Gourville EM, Dowdle WR, Pallansch MA. Vaccine-derived polioviruses and the endgame strategy for global polio eradication. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2005;59:587–635. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tosh PK, Boyce TG, Poland GA. Flu myths: dispelling the myths associated with live attenuated influenza vaccine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(1):77–84. doi: 10.4065/83.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenney JL, Volk SM, Pandya J, Wang E, Liang X, Weaver SC. Stability of RNA virus attenuation approaches. Vaccine. 2011;29(12):2230–2234. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sauder CJ, Vandenburgh KM, Iskow RC, Malik T, Carbone KM, Rubin SA. Changes in mumps virus neurovirulence phenotype associated with quasispecies heterogeneity. Virology. 2006;350(1):48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burch CL, Turner PE, Hanley KA. Patterns of epistasis in RNA viruses: a review of the evidence from vaccine design. J Evol Biol. 2003;16(6):1223–1235. doi: 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Victoria JG, Wang C, Jones MS, Jaing C, McLoughlin K, Gardner S, Delwart EL. Viral nucleic acids in live-attenuated vaccines: detection of minority variants and an adventitious virus. J Virol. 2010;84(12):6033–6040. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02690-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valsamakis A, Auwaerter PG, Rima BK, Kaneshima H, Griffin DE. Altered virulence of vaccine strains of measles virus after prolonged replication in human tissue. J Virol. 1999;73(10):8791–8797. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8791-8797.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odoom JK, Yunus Z, Dunn G, Minor PD, Martin J. Changes in population dynamics during long-term evolution of sabin type 1 poliovirus in an immunodeficient patient. J Virol. 2008;82(18):9179–9190. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00468-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fine P, Eames K, Heymann DL. “Herd immunity”: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(7):911–916. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roivainen M, Blomqvist S, al-Hello H, Paananen A, Delpeyroux F, Kuusi M, Hovi T. Highly divergent neurovirulent vaccine-derived polioviruses of all three serotypes are recurrently detected in Finnish sewage. Euro Surveill. 2010;15:19566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zurbriggen S, Tobler K, Abril C, Diedrich S, Ackermann M, Pallansch MA, Metzler A. Isolation of sabin-like polioviruses from wastewater in a country using inactivated polio vaccine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(18):5608–5614. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02764-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heinsbroek E, Ruitenberg EJ. The global introduction of inactivated polio vaccine can circumvent the oral polio vaccine paradox. Vaccine. 2010;28(22):3778–3783. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Minor P. Vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV): Impact on poliomyelitis eradication. Vaccine. 2009;27(20):2649–2652. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Condit RC. Principles of Virology. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology. Fifth edn vol. One. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monath TP. Yellow fever vaccine. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2005;4(4):553–574. doi: 10.1586/14760584.4.4.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monath TP, Cetron MS, Teuwen DE. Yellow fever vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, editors. Vaccines. Fifth edn Saunders, Elsevier; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitehead SS, Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR. Prospects for a dengue virus vaccine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(7):518–528. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Condack C, Grivel JC, Devaux P, Margolis L, Cattaneo R. Measles virus vaccine attenuation: suboptimal infection of lymphatic tissue and tropism alteration. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(4):541–549. doi: 10.1086/519689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miki NP, Chantler JK. Differential ability of wild-type and vaccine strains of rubella virus to replicate and persist in human joint tissue. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1992;10(1):3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zou G, Zhang B, Lim PY, Yuan Z, Bernard KA, Shi PY. Exclusion of West Nile virus superinfection through RNA replication. J Virol. 2009;83(22):11765–11776. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01205-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dang Q, Chen J, Unutmaz D, Coffin JM, Pathak VK, Powell D, KewalRamani VN, Maldarelli F, Hu WS. Nonrandom HIV-1 infection and double infection via direct and cell-mediated pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(2):632–637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307636100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cicin-Sain L, Podlech J, Messerle M, Reddehase MJ, Koszinowski UH. Frequent coinfection of cells explains functional in vivo complementation between cytomegalovirus variants in the multiply infected host. J Virol. 2005;79(15):9492–9502. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9492-9502.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith DR, Adams AP, Kenney JL, Wang E, Weaver SC. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus in the mosquito vector Aedes taeniorhynchus: infection initiated by a small number of susceptible epithelial cells and a population bottleneck. Virology. 2008;372(1):176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Joseph SB, Hanley KA, Chao L, Burch CL. Coinfection rates in φ6 bacteriophage are enhanced by virus-induced changes in host cell. Evol Appl. 2009;2:24–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2008.00055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Wang H, Zhu S, Li Y, Song L, Liu Y, Liu G, Nishimura Y, Chen L, Yan D, et al. Characterization of a rare natural intertypic type 2/type 3 penta-recombinant vaccine-derived poliovirus isolated from a child with acute flaccid paralysis. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 2):421–429. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.014258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mochizuki M, Ohshima T, Une Y, Yachi A. Recombination between vaccine and field strains of canine parvovirus is revealed by isolation of virus in canine and feline cell cultures. J Vet Med Sci. 2008;70(12):1305–1314. doi: 10.1292/jvms.70.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.He CQ, Ma LY, Wang D, Li GR, Ding NZ. Homologous recombination is apparent in infectious bursal disease virus. Virology. 2009;384(1):51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thiry E, Muylkens B, Meurens F, Gogev S, Thiry J, Vanderplasschen A, Schynts F. Recombination in the alphaherpesvirus bovine herpesvirus 1. Vet Microbiol. 2006;113(3-4):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Estevez C, Villegas P, El-Attrache J. A recombination event, induced in ovo, between a low passage infectious bronchitis virus field isolate and a highly embryo adapted vaccine strain. Avian Dis. 2003;47(4):1282–1290. doi: 10.1637/5919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weaver SC, Kang W, Shirako Y, Rumenapf T, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. Recombinational history and molecular evolution of western equine encephalomyelitis complex alphaviruses. J Virol. 1997;71(1):613–623. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.613-623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hahn CS, Lustig S, Strauss EG, Strauss JH. Western equine encephalitis virus is a recombinant virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(16):5997–6001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.16.5997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sabin AB, Ramos-Alvarez M, Alvarez-Amezquita J, Pelon W, Michaels RH, Spigland I, Koch MA, Barnes JM, Rhim JS. Live, orally given poliovirus vaccine. Effects of rapid mass immunization on population under conditions of massive enteric infection with other viruses. JAMA. 1960;173:1521–1526. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020320001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nascimento Silva JR, Camacho LA, Siqueira MM, Freire MD, Castro YP, Maia MD, Yamamura AM, Martins RM, Leal MD. Mutual interference on the immune response to yellow fever vaccine and a combined vaccine against measles, mumps and rubella. Vaccine. 2011;29:6327–34. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agrawal N, Mane M, Chiriva-Internati M, Roman JJ, Hermonat PL. Temporal acceleration of the human papillomavirus life cycle by adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 superinfection in natural host tissue. Virology. 2002;297(2):203–210. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Allan GM, Caprioli A, McNair I, Lagan-Tregaskis P, Ellis J, Krakowka S, McKillen J, Ostanello F, McNeilly F. Porcine circovirus 2 replication in colostrum-deprived piglets following experimental infection and immune stimulation using a modified live vaccine against porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus. Zoonoses Public Health. 2007;54(5):214–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2007.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Allan GM, McNeilly F, Ellis J, Krakowka S, Meehan B, McNair I, Walker I, Kennedy S. Experimental infection of colostrum deprived piglets with porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) potentiates PCV2 replication. Arch Virol. 2000;145(11):2421–2429. doi: 10.1007/s007050070031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim DY, Atasheva S, Foy NJ, Wang E, Frolova EI, Weaver S, Frolov I. Design of chimeric alphaviruses with a programmed, attenuated, cell type-restricted phenotype. J Virol. 2011;85(9):4363–4376. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00065-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lim KI, Lang T, Lam V, Yin J. Model-based design of growth-attenuated viruses. PLoS Comput Biol. 2006;2(9):e116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hanley KA, Manlucu LR, Gilmore LE, Blaney JE, Jr., Hanson CT, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. A trade-off in replication in mosquito versus mammalian systems conferred by a point mutation in the NS4B protein of dengue virus type 4. Virology. 2003;312(1):222–232. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Blaney JE, Durbin AP, Murphy BR, Whitehead SS. Development of a Live Attenuated Dengue Virus Vaccine Using Reverse Genetics. Viral Immunol. 2006;19:10–32. doi: 10.1089/vim.2006.19.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vignuzzi M, Wendt E, Andino R. Engineering attenuated virus vaccines by controlling replication fidelity. Nat Med. 2008;14(2):154–161. doi: 10.1038/nm1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mueller S, Coleman JR, Papamichail D, Ward CB, Nimnual A, Futcher B, Skiena S, Wimmer E. Live attenuated influenza virus vaccines by computer-aided rational design. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(7):723–726. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Coleman JR, Papamichail D, Skiena S, Futcher B, Wimmer E, Mueller S. Virus attenuation by genome-scale changes in codon pair bias. Science. 2008;320(5884):1784–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1155761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boni MF. Vaccination and antigenic drift in influenza. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 3):C8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Catelli E, Lupini C, Cecchinato M, Ricchizzi E, Brown P, Naylor CJ. Field avian metapneumovirus evolution avoiding vaccine induced immunity. Vaccine. 2010;28(4):916–921. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cecchinato M, Catelli E, Lupini C, Ricchizzi E, Clubbe J, Battilani M, Naylor CJ. Avian metapneumovirus (AMPV) attachment protein involvement in probable virus evolution concurrent with mass live vaccine introduction. Vet Microbiol. 2010;146(1-2):24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Park KJ, Kwon HI, Song MS, Pascua PN, Baek YH, Lee JH, Jang HL, Lim JY, Mo IP, Moon HJ, et al. Rapid evolution of low-pathogenic H9N2 avian influenza viruses following poultry vaccination programmes. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 1):36–50. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.024992-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee CW, Senne DA, Suarez DL. Effect of vaccine use in the evolution of Mexican lineage H5N2 avian influenza virus. J Virol. 2004;78(15):8372–8381. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.15.8372-8381.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gandon S, Mackinnon M, Nee S, Read A. Imperfect vaccination: some epidemiological and evolutionary consequences. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270(1520):1129–1136. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mackinnon MJ, Gandon S, Read AF. Virulence evolution in response to vaccination: the case of malaria. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 3):C42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gandon S, Day T. The evolutionary epidemiology of vaccination. J R Soc Interface. 2007;4(16):803–817. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Andre JB, Gandon S. Vaccination, within-host dynamics, and virulence evolution. Evolution. 2006;60(1):13–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ganusov VV, Antia R. Imperfect vaccines and the evolution of pathogens causing acute infections in vertebrates. Evolution. 2006;60(5):957–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Massad E, Coutinho FA, Burattini MN, Lopez LF, Struchiner CJ. The impact of imperfect vaccines on the evolution of HIV virulence. Med Hypotheses. 2006;66(5):907–911. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Manuel ER, Yeh WW, Balachandran H, Clarke RH, Lifton MA, Letvin NL. Vaccination reduces simian-human immunodeficiency virus sequence reversion through enhanced viral control. J Virol. 2010;84(24):12782–12789. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01193-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Castillo-Solorzano CC, Matus CR, Flannery B, Marsigli C, Tambini G, Andrus JK. The americas: paving the road toward global measles eradication. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(Suppl 1):S270–278. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moss WJ. Measles control and the prospect of eradication. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;330:173–189. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-70617-5_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rimoin AW, Mulembakani PM, Johnston SC, Smith JO Lloyd, Kisalu NK, Kinkela TL, Blumberg S, Thomassen HA, Pike BL, Fair JN, et al. Major increase in human monkeypox incidence 30 years after smallpox vaccination campaigns cease in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(37):16262–16267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005769107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rieder E, Gorbalenya AE, Xiao C, He Y, Baker TS, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG, Wimmer E. Will the polio niche remain vacant? Dev Biol (Basel) 2001;105:111–122. discussion 149-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vasilakis N, Cardosa J, Hanley KA, Holmes EC, Weaver SC. Fever from the forest: prospects for the continued emergence of sylvatic dengue virus and its impact on public health. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(7):532–541. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Theiler M, Smith HH. The Use of Yellow Fever Virus Modified by in Vitro Cultivation for Human Immunization. J Exp Med. 1937;65(6):787–800. doi: 10.1084/jem.65.6.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takahashi M, Asano Y, Kamiya H, Baba K, Ozaki T, Otsuka T, Yamanishi K. Development of varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(Suppl 2):S41–44. doi: 10.1086/522132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]