Abstract

Limited understanding of the mechanisms underlying self-renewal and differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells hampers our ability to develop new therapeutic and contraceptive approaches. Mouse models of spermatogonial stem cell development are key to developing new insights into the biology of both the normal and diseased testis. Advances in transgenic reporter mice have enabled the isolation, molecular characterization, and functional analysis of mouse Type A spermatogonia subpopulations from the normal testis, including populations enriched for spermatogonial stem cells. Application of these reporters both to the normal testis and to gene-deficient and over-expression models will promote a better understanding of the earliest steps of spermatogenesis, and the role of spermatogonial stem cells in germ cell tumor.

Keywords: Reporter mice, undifferentiated spermatogonia, Pou5f1, green fluorescent protein, fluorescence-activated cell sorting

1. Introduction

The use of GFP (green fluorescent protein)-reporter mice for the in vivo and ex vivo identification of specific cells from a heterogeneous population is unsurpassed in terms of ease and accuracy. GFP-reporter mice that have been successfully developed for the identification of postnatal germ cells include Dazl-GFP (1), Neurog3-GFP (2), Stra8-GFP (3), and Pou5f1-GFP (4). Of these, the Pou5f1-GFP reporter mouse is unique in that it allows visualization of Pou5f1 positive (+) cells (5, 6), which in adult males marks early Type A spermatogonia (7, 8). Pou5f1+ cells may be further divided based on their expression of the cell surface receptor, Kit (also referred to as c-Kit) (4). As Kit is a marker for differentiating spermatogonia (9), Pou5f1+/Kit-cells comprise undifferentiated spermatogonia, whereas Pou5f1+/Kit+ cells are constituents of the earliest steps of differentiation (Fig. 1). Therefore, Pou5f1+ cells as a whole are a mixture of undifferentiated and early differentiating Type A spermatogonia. This notion is supported by transplantation studies that have shown Pou5f1+/Kit+ cells are inefficient at colonizing a germ-cell depleted testis relative to Pou5f1+/Kit- transplanted cells (4, 10, 11).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of spermatogenesis in the prepubertal and adult mouse testis showing the expression time-course of Pou5f1 and Kit. Spermatogenesis begins with mitotic proliferation and differentiation of diploid, undifferentiated spermatogonia. Differentiating spermatogonia unidirectionally continue differentiation into spermatocytes, which undergo two meiotic divisions to form haploid spermatids. Haploid spermatids undergo dramatic structural modifications leading up to the formation of spermatozoa. The time from the initiation of differentiation to the formation of spermatozoa is a period of several weeks. Day 7 testis only contain spermatogenic cells up to Type B spermatogonia; Day 10 testis only contain spermatogenic cells up to leptotene spermatocytes (28). Diagrams do not depict the relative proportion of each cell population.

Our intention here is not to review Pou5f1 (also referred to as Oct4) as an embryonic stem (ES) cell and pluripotency marker, nor go into great detail describing the constructs used to create the transgenic reporter strains based on the Pou5f1 gene promoter. Since several publications and reviews effectively cover these and many other aspects (10, 12, 13), rather we present here several features relevant to the use of the Pou5f1-GFP reporter mouse for postnatal Type A spermatogonia identification and isolation (Fig. 2). In particular we will describe fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based techniques that can yield either a mixture or separate populations of undifferentiated and early differentiating spermatogonia. Once isolated, these cells may be useful for downstream analyses such as examination of genes differentially regulated during self-renewal and early differentiation (Fig. 3).

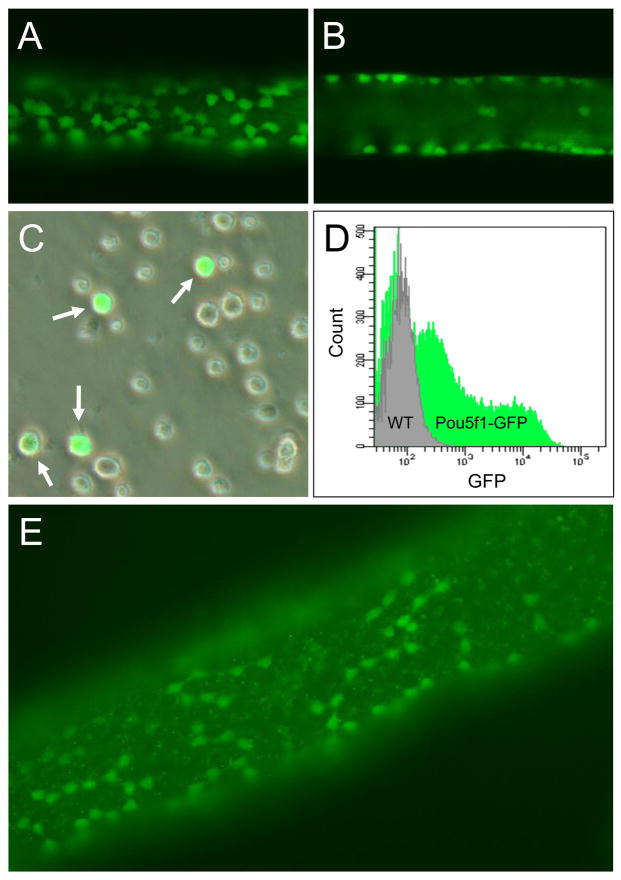

Figure 2.

Fluorescence micrograph and flow cytometric evaluation of freshly isolated tubules and cells isolated from Pou5f1-GFPMann mice. (A–B) Logitudinal cross-section adjacent to basement membrane (A) and through lumen (B) of a live, freshly isolated Pou5f1-GFPMann seminiferous tubule, demonstrating distribution of GFP+ spermatogonia along the basement membrane at 10 dpp. (C) GFP+ cells (arrows) in a freshly isolated, non-enriched primary cell population from 10 dpp Pou5f1-GFPMann mice. (D) Flow cytometry fluorescence intensity profile of wild-type (control) and Pou5f1-GFPMann freshly isolated cells from 10 dpp mice demonstrating a large population of GFP+ spermatogonia available for specific isolation through Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). (E) Representative fluorescence micrograph of a freshly isolated tubule isolated from Pou5f1-GFPMann mice at 100 dpp demonstrating Aaligned spermatogonia.

Figure 3.

Undifferentiated and early differentiating spermatogonia isolated through Fluorescence Activated Cell Sorting (FACS). (A) Flow-cytometric analysis and sorting of wild-type and Pou5f1-GFPMann cells stained with APC-Kit antibody. (B) Real-time-PCR analysis of Kit and canonical markers of undifferentiated spermatogonia in Pou5f1+/Kit- and Pou5f1+/Kit+ cells sorted from A. Cells were processed for RT-PCR using the TaqMan Gene Expression Cells-to-CT Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The expression value of each gene was normalized to the amount of an internal control gene (Eif3land Rps3) (29) and a relative quantitative fold change was determined using the ΔΔ Ct method. Experiments were performed in triplicate and data are represented as mean ± standard error. Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) used for specific transcripts were: Mm00460859_m1 (Eif3l), Mm00833897_m1 (Gfra1), Mm00445212_m1 (Kit), Mm00437606_s1 (Neurog3), Mm00658129_gH (Pou5f1), Mm00656272_m1 (Rps3), Mm00493681_m1 (Thy1), and Mm01176868_m1 (Zbtb16). Normalization to Eif3l and Rps3 produced identical results.

1.1 Reporter Strain Specific Differences

Choice of Pou5f1-GFP reporter strain is important, as several strains that have become available do not express GFP in postnatal or adult germ cells. The one strain that is successful for identifying a specific subpopulation of germ cells up to late adulthood (as demonstrated by our lab; Fig. 2E) is the transgenic strain B6;CBA-Tg(Pou5f1-EGFP)2Mnn/J (hereafter referred to as Pou5f1-GFPMann). Originally reported in Szabo et al. (2002), this strain is currently available through The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) (14). In comparison, we found that a knock-in reporter strain originally reported in Lengner et al. (2007) (15)—now available through The Jackson Laboratory as B6;129S4-Pou5f1tm2Jae/J—does not express GFP in postnatal testis. Furthermore, the transgenic strain originally reported in Ohbo et al. (2003), although generated similar to Pou5f1-GFPMann, reports Type A spermatogonia during the first wave of spermatogenesis—up to approximately 10 days postpartum (dpp)—but not during subsequent waves (4, 16). Although the mechanism underlying these strain specific differences is uncertain, differences in the genomic location of the transgene and differential epigenetic silencing of these regions may likely play a role, as has been reported for other reporters and transgenes (17–19).

1.2 In vitro use

The Pou5f1-GFP reporter has been used with much success for labeling induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells and embryonic stem (ES) cells in culture (20, 21). GFP+ type A spermatogonia from Pou5f1-GFPMann testes are detectable in situ and can be isolated from the other cells of the seminiferous epithelium by FACS (Fig. 2). However, they begin to lose GFP expression at the onset of culture. By 72 hr in culture, the signal becomes undetectable, but cells continue to grow. Interestingly, GFP expression re-emerges after 3–4 weeks of culture. This observation was originally reported by Izadyar and colleagues (10) and confirmed in our lab using a variety of culture conditions supporting short and long-term expansion of mouse SSCs (22–25). Therefore, the usefulness of this particular reporter strain for in vitro studies is limited in this respect.

2. Materials

2.1 Mice

2.2 Buffers and Enzyme Solutions

Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) (Invitrogen)

Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) with Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Invitrogen)

Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Invitrogen)

Cell Dissociation Buffer, enzyme free, Hanks’-based (Invitrogen)

Collagenase IV/DNase solution: Prepare 1 mg/ml Type IV collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 2 μg/ml DNase (Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM/F12. Filter-sterilize through a 0.22-μm filter, aliquot and freeze at −20 or −80 °C. Thaw at room temperature immediately before use.

Trypsin/DNase solution: Dissolve DNase in 0.25% (wt/vol) Trypsin with EDTA (Invitrogen) to a concentration of 200 μg/ml. Filter-sterilize through a 0.22 μm filter, aliquot and freeze at −20 or −80 °C. Thaw at room temperature immediately before use.

S-HBSS buffer (Supplemented HBSS buffer) (26): Prepare 20 mM HEPES, 6.6 mM sodium pyruvate, and 0.05% sodium lactate in HBSS with Ca2+ and Mg2+. Filter-sterilize through a 0.22 μm filter and store at 4 °C for up to 3 weeks.

Collagenase I solution: Dissolve Type I collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) in S-HBSS to a concentration of 100 U/ml. Filter-sterilize through a 0.22-μm filter. Make fresh immediately before use.

FACS buffer (PBS-S) (27): Prepare 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM Pyruvate, 1 mg/ml glucose, 1% FBS (vol/vol), and 1× penicillin/streptomycin in 1× DPBS. Filter-sterilize through a 0.22 μm filter and store at 4 °C for up to 3 weeks.

Trypan Blue, 0.4% Solution (Sigma-Aldrich)

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) stock solution: Dissolve 1 mg of DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich) in 100 ml of dH2O. Protect from light and store at 4 °C for up to 3 weeks. For long-term storage, aliquot and freeze at −20 °C.

2.3 Supplies and Equipment

Dissecting stereomicroscope with fiber-optic light source

Dissection scissors

Fine-tip forceps

Class II, Type A2 HEPA-filtered biosafety cabinet

Microcentrifuge, preferably with temperature control for maintenance at 4 °C

Benchtop centrifuge with buckets suitable for 15 and 50 ml conical tubes, preferably with temperature control for maintenance at 4 °C

Inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus IX70, or similar) equipped with phase contrast objectives (phase × 4, × 10, × 20, × 40)

Cell counter or hemocytometer

Small end-over-end rotator

BD FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), or similar, with BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences), or similar, for data acquisition

CO2 incubator with CO2, humidity and temperature control and monitoring

Water Bath Shaker (New Brunswick Scientific C76, or similar)

2.4 Plasticware/disposables

Sterile 100 mm petri dishes

Sterile 10 and 25 ml disposable pipettes

0.22 μm, 150 ml, sterile disposable filter systems (Nalgene)

Sterile 15 and 50 ml polypropylene conical tubes

Sterile 1.5 ml polypropylene microcentrifuge tubes

40 and 70 μm nylon mesh cell strainers (BD Biosciences)

5 ml (12 × 75 mm) polypropylene round bottom FACS collection tubes. (BD Biosciences)

5 ml (12×75 mm) polypropylene round bottom FACS collection tube with 35 μm nylon mesh cell strainer cap (BD Biosciences)

3. Methods

Single cell suspensions of mouse testicular cells enriched for seminiferous epithelium cells (germ cells and Sertoli cells) are isolated from a pool of Pou5f1-GFPMann pups that are 7–10 days postpartum (see Note 2). Four to eight pups are used per isolation, although a greater number may be necessary, in which case the volumes and vessels used should be scaled up proportionally. Using 4–8 pups, the yield will range from 1–2.5 × 106 cells/pup; 4–20 × 106 cells total.

3.1 Basic Germ Cell Isolation

3.1.1 Seminiferous tubule isolation

Sacrifice pups, aseptically excise testes with adjoining epidydimis, and pool into one 100 mm Petri dish containing chilled DMEM/F-12. If a large number of testes are collected and/or an accumulation of blood and debris is present, tissues may be transferred individually with forceps to a new 100 mm Petri dish containing fresh DMEM/F-12 to wash.

With a fine-tipped forcep in one hand, secure one testis by the efferent ducts, and with a second fine-tipped forcep in closed position in the other hand, puncture the tunica albuginea. With the tips of the closed forcep still inside the testis, allow the tips to spread apart, tearing the tunica albuginea open and exposing the seminiferous tubules. Once the seminiferous tubules are sufficiently exposed, in a second continuous motion using the same forcep to puncture/spread, extract the seminiferous tubules, which with practice can typically be done in entirety with one intact clump.

Transfer seminiferous tubule clumps into one 15 ml conical tube on ice containing 5–10 ml of fresh DMEM/F-12 (see Note 3). Pool tubule clumps from age-matched non-reporter pups (flow cytometry negative control for GFP expression) into a separate tube and process in parallel.

3.1.2 Sequential digestion: Concept

For the isolation of seminiferous epithelium cells and concomitant depletion of interstitial cells (blood cells, peritubular myoid cells, and Leydig cells), a two-step digestion protocol is used. The first gentle collagenase digestion breaks the aggregated tubules and tubule clumps into individual tubule fragments, and releases the interstitial cells into solution. Tubule fragments are allowed to settle at 1 unit gravity, and the interstitial cells, which will remain in the supernatant, are removed. Gravity sedimentation is repeated again during a wash step and the cleaned up tubule fragments are resuspended and incubated in trypsin solution or cell dissociation buffer with mechanical disruption. After straining to remove any undissociated cells and agglomerated cellular debris, the resulting single cell suspension can be processed for FACS.

3.1.3 Tubule fragmentation and cleanup (FACS isolation of Pou5f1+ cells only)

Ensure all tubule clumps have settle to the bottom of the tube.

Suction/pipette off DMEM/F-12, add 4–8 ml freshly thawed Collagenase IV solution, and pipette up and down gently several times (see Note 4).

Incubate at room temp for 1–2 min, pipette up and down gently several times again, and observe the status of the tubules. At this point, tubules should dissociate into tubule fragments. Repeat this step only if tubule clumps have not become dissociated. If only a small tubule clump remains, the following steps will complete the fragmentation process.

Allow the tubules to sediment, which can take as little as 2 min, but should not exceed 5 min to ensure the single dissociated interstitial cells remain in the supernatant.

Next resuspend the settled tubule fragments in an equal volume of DPBS without Ca2+ or Mg2+, and pipette up and down gently (or invert if tubules are fragmented) and allow the tubule fragments to sediment again as described above (see Note 5).

3.1.4 Trypsin digestion (for FACS isolation of Pou5f1+ cells)

Once the tubule fragments have sedimented, remove DPBS, and resuspend tubule fragments in an equal volume of trypsin solution and incubate at room temperature with intermittent pipetting (see Note 6).

Total incubation time in trypsin solution—to yield a single cell suspension with only few small intact tubule fragments remaining—ranges from 5 to 10 minutes, but can take longer if the activity of trypsin in low (see Note 7).

Digestion with intermittent pipetting is continued until completed and followed by addition of FBS to a final concentration of 10%, to quench trypsin activity. Subsequent steps are carried out at 4 °C.

The cells are centrifuged at 300 × g for 7 min, then washed and resuspended in FACS buffer.

Passage of cells through a 70 and/or 40 μm strainer to obtain a single cell suspension can take place any step after trypsin has been inactivated (see Note 8).

Count cells using a viability dye such as trypan blue to determine viable and non-viable cell numbers.

3.2 Modifications of basic germ cell isolation for preservation of cell surface antigens (for FACS isolation of Pou5f1+/Kit- and Pou5f1+/Kit+ cells)

Since trypsin will act proteolytically upon cell surface proteins, to ensure preservation of cell surface antigens and optimal staining of Kit receptor, the non-trypsin based isolation protocol of Vincent et al. (1998) is used (26).

3.2.1 Tubule fragmentation and cleanup (FACS isolation of Pou5f1+ cells only)

Instead of Collagenase IV solution, use freshly prepared Collagenase I solution and extend the incubation conditions from approximately 5 min at room temp with occasional pipetting, to 20–30 min in a reciprocating water bath at 32 °C (see Note 9).

Pellet tubule fragments through gravity sedimentation, extending incubation to 10 min if necessary to ensure small tubule fragments have sedimented. If a fluorescence microscope is nearby during the isolation, microscopic evaluation of the suspension before and after sedimentation is helpful in confirming that the single cells remaining in suspension are depleted of GFP+ cells. If too many GFP+ cells were released during Collagenase I digestion, proceed to centrifuging the entire contents at 300 × g for 7 min to ensure full recovery. Remove supernatant.

Resuspend pellet in HBSS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ to wash and centrifuge at 300 × g for 7 min.

Resuspend pellet in Cell Dissociation Buffer and incubate for 20–30 minutes at 32 °C in a reciprocating water bath set at slow speed.

Pipette up and down to dissociate the cells further, and observe the cell suspension microscopically to determine whether a large quantity of single cells has been released. If not, incubate further with additional pipetting, then filter through a 40 μm nylon mesh to remove cell clumps (see Note 10).

Count cells using a viability dye such as trypan blue to determine viable and non-viable cell numbers.

3.2.2 Kit receptor staining

Once the cells are harvested according to the methods of Vincent et al. (1998), the cell suspension is adjusted to a concentration of 1×107 cells/ml in FACS buffer (see Notes 11 and 12).

Add allophycocyanin (APC) conjugated anti-mouse CD117 (Kit) antibody (BD Biosciences) to cells at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml and incubate with slow end-over-end rotation at 4 °C for 30 min in the dark (see Note 13).

Wash the cells 3 times with FACS buffer (wash volume same as incubation volume) and resuspend the final cell suspension again at a concentration of 1×107 cells/ml in FACS buffer.

The cells should be protected from light on ice or in a fridge until they are processed (see Note 14).

3.2.3 Preparation of FACS collection tubes

The day before cell sorting, fill FACS collection tubes entirely with DMEM/F12 + 10% FBS and store in refrigerator overnight to pre-coat tubes (see Note 15).

Transfer prepared cells and DMEM/F12 + 10% FBS filled tubes on ice to FACS instrument.

Immediately preceding sort, remove approximately 50% volume of DMEM/F12 + 10% FBS used to pre-coat tubes and collect instrument-sorted cells into pre-coated FACS collection tubes kept chilled at 4 °C during sort.

3.3.3 FACS controls

Autofluorescence and fluorescence spillover are eliminated during FACS through proper set-up and initial compensation of the flow cytometer; thorough use of no fluorophore and single fluorophore controls prior to each run is imperative. Testicular cells simultaneously isolated from age-matched wild-type mice (as mentioned above) are run through the instrument first to set the cutoff value for background fluorescence. Unstained Pou5f1-GFP cells and APC-Kit antibody stained wild-type cells are used for compensating between the multiple color channels.

3.3.4 FACS Instrument

In our studies, the instrument used was the BD FACS Aria II cell sorter. With this instrument DAPI is excited with a UV 355 nm solid state laser and emission light is detected through a 450/50 nm bandpass filter; GFP is excited with a blue 488 nm solid state laser and emission light is detected through a 530/30 nm bandpass filter; APC is excited with a red 640 nm solid state laser and emission light is detected through a 670/30 nm bandpass filter. The BD FACSDiva software is used to control the instrument before and during data acquisition and for data analysis during and after the run. Samples are sorted at 4 °C using an 85 μm nozzle and 45 p.s.i. pressure.

3.4.5 Sorting

Immediately prior to processing samples, add 5 μl DAPI stock solution per 1 ml cells (see Note 16).

Gate for DAPI negative cells to exclude dead cells (see Note 16).

Gate for singlets on a plot of forward scatter area (FSC-A) versus forward scatter width (FSC-W) to ensure ultimate purity.

For sorting GFP+ cells only, gate for GFP+ cells on a plot of GFP vs. FSC-A, using wild-type cells to determine the cutoff value for background fluorescence. For sorting Pou5f1+/Kit- and Pou5f1+/Kit+ cells separately, gate for each population on a plot of GFP versus APC intensity (see Fig 3A).

Sort cells/events from gated regions of interest into pre-coated tubes (as mentioned above). Maintain tubes at 4 °C or on ice during and after the sort.

When isolating cells from 8 dpp mice, one can expect to retrieve approximately 20% GFP+ cells; if stained for c-Kit, roughly two-thirds will be Pou5f1+/Kit- and one-third Pou5f1+/Kit+.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Barbara Pilas and Ben Montez from the R. J. Carver Biotechnology Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for their invaluable assistance with flow cytometry and comments on the manuscript. The authors are also grateful to the NIH for funding this work.

Abbreviations

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- APC

allophycocyanin

- dpp

days postpartum

Footnotes

All experiments involving live mice must conform to national and institutional regulations.

This age is selected so as to enrich for premeiotic germ cells, in particular Type A spermatogonia, and to obtain the highest overall yield possible (28).

As a rule of thumb, use 1 ml per 2–4 testes. Therefore, for a small-scale isolation from 1–2 pups, one 1.5 ml eppendorf tube may be used for all steps. Otherwise, isolation from 8 pups (16 testes) will require at least 4 ml solution in a 15 ml conical tube; isolation from greater than 12 pups should be carried out in a 50 ml conical tube.

Use the lower volume of 4 ml if isolating from 7 day old mice, and the higher volume of 8 ml if isolating from 10 day olds.

DPBS without Ca2+ or Mg2+ is used since the testis isolation and collagenase digestion was performed in DMEM/F12 to ensure optimal health, however contains Ca2+ and Mg2+, which promotes cell-to-cell adhesion.

Assuming the activity of trypsin is good, it is better to perform the trypsin digestion at room temperature rather than 37 °C, as this allows one to make several separate microscopic observations of the status of digestion using a nearby microscope, with a lower likelihood of over digestion.

If trypsin activity is low, trypsin activity may be increased by placing the tube in a 37 °C bath (without shaking) to warm.

If very little insoluble debris is present, to obtain the most cells, it is preferable to strain after the last wash, since cells may continue to dissociate during washes. However, if a significant amount of insoluble debris is observed after the trypsin digestion (if some overdigestion has taken place), it may be desirable to strain before the first centrifugation, with a second straining step after the last wash.

Collagenase I is used instead of Collagenase IV since it is gentler, yet allows for increased fragmentation and dissociation of the basement membrane, facilitating subsequent non-enzymatic digestion.

With the cell dissociation buffer protocol, complete digestion of all tubule fragments into single cells is less efficient than with trypsin, and a yield closer to 0.5–1 × 106 cells/pup should be expected; however, cell surface antigenicity will be retained. Scale-up accordingly if a greater number of cells are required.

Cells are stained in 1.5 ml eppendorf tubes, although any suitable container may be used.

All staining procedures should be carried out with ice-cold reagents and on wet ice or at 4 °C to suppress gene expression changes.

Since antibody binding efficiency and fluorescence intensity may vary based on lot and investigator handling, an initial antibody titration should be performed to obtain optimal results.

For best results, sort the cells as soon as possible, but the cells can be maintained in FACS buffer for several hours.

If collection tubes are uncoated, cells will adhere to the inside of the tubes, making recovery difficult and significantly decreasing yield.

Dead cell exclusion using DAPI may be excluded during the sort if cell viability was 100% as determined during cell counting with trypan blue.

References

- 1.Nicholas CR, Xu EY, Banani SF, Hammer RE, Hamra FK, Reijo Pera RA. Characterization of a Dazl-GFP germ cell-specific reporter. Genesis. 2009;47:74–84. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoshida S, Takakura A, Ohbo K, Abe K, Wakabayashi J, Yamamoto M, Suda T, Nabeshima Y. Neurogenin3 delineates the earliest stages of spermatogenesis in the mouse testis. Dev Biol. 2004;269:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nayernia K, Li M, Jaroszynski L, Khusainov R, Wulf G, Schwandt I, Korabiowska M, Michelmann HW, Meinhardt A, Engel W. Stem cell based therapeutical approach of male infertility by teratocarcinoma derived germ cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1451–1460. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ohbo K, Yoshida S, Ohmura M, Ohneda O, Ogawa T, Tsuchiya H, Kuwana T, Kehler J, Abe K, Scholer HR, Suda T. Identification and characterization of stem cells in prepubertal spermatogenesis in mice small star, filled. Dev Biol. 2003;258:209–225. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeom YI, Fuhrmann G, Ovitt CE, Brehm A, Ohbo K, Gross M, Hubner K, Scholer HR. Germline regulatory element of Oct-4 specific for the totipotent cycle of embryonal cells. Development. 1996;122:881–894. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshimizu T, Sugiyama N, De Felice M, Yeom YI, Ohbo K, Masuko K, Obinata M, Abe K, Scholer HR, Matsui Y. Germline-specific expression of the Oct-4/green fluorescent protein (GFP) transgene in mice. Dev Growth Differ. 1999;41:675–684. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.00474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pesce M, Wang X, Wolgemuth DJ, Scholer H. Differential expression of the Oct-4 transcription factor during mouse germ cell differentiation. Mech Dev. 1998;71:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tadokoro Y, Yomogida K, Ohta H, Tohda A, Nishimune Y. Homeostatic regulation of germinal stem cell proliferation by the GDNF/FSH pathway. Mech Dev. 2002;113:29–39. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schrans-Stassen BH, van de Kant HJ, de Rooij DG, van Pelt AM. Differential expression of c-kit in mouse undifferentiated and differentiating type A spermatogonia. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5894–5900. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.12.7172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izadyar F, Pau F, Marh J, Slepko N, Wang T, Gonzalez R, Ramos T, Howerton K, Sayre C, Silva F. Generation of multipotent cell lines from a distinct population of male germ line stem cells. Reproduction. 2008;135:771–784. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shinohara T, Orwig KE, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Spermatogonial stem cell enrichment by multiparameter selection of mouse testis cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8346–8351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boiani M, Kehler J, Scholer HR. Activity of the germline-specific Oct4-GFP transgene in normal and clone mouse embryos. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;254:1–34. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-741-6:001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond SS, Matin A. Tools for the genetic analysis of germ cells. Genesis. 2009;47:617–627. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabo PE, Hubner K, Scholer H, Mann JR. Allele-specific expression of imprinted genes in mouse migratory primordial germ cells. Mech Dev. 2002;115:157–160. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lengner CJ, Camargo FD, Hochedlinger K, Welstead GG, Zaidi S, Gokhale S, Scholer HR, Tomilin A, Jaenisch R. Oct4 expression is not required for mouse somatic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohmura M, Yoshida S, Ide Y, Nagamatsu G, Suda T, Ohbo K. Spatial analysis of germ stem cell development in Oct-4/EGFP transgenic mice. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67:285–296. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garrick D, Fiering S, Martin DI, Whitelaw E. Repeat-induced gene silencing in mammals. Nat Genet. 1998;18:56–59. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garrick D, Sutherland H, Robertson G, Whitelaw E. Variegated expression of a globin transgene correlates with chromatin accessibility but not methylation status. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4902–4909. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.24.4902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henikoff S. Conspiracy of silence among repeated transgenes. Bioessays. 1998;20:532–535. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199807)20:7<532::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meissner A, Wernig M, Jaenisch R. Direct reprogramming of genetically unmodified fibroblasts into pluripotent stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1177–1181. doi: 10.1038/nbt1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen S, Do JT, Zhang Q, Yao S, Yan F, Peters EC, Scholer HR, Schultz PG, Ding S. Self-renewal of embryonic stem cells by a small molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17266–17271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608156103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan K, Wolf F, Becker A, Engel W, Nayernia K, Hasenfuss G. Isolation and cultivation of stem cells from adult mouse testes. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:143–154. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hofmann MC, Braydich-Stolle L, Dym M. Isolation of male germ-line stem cells; influence of GDNF. Dev Biol. 2005;279:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanatsu-Shinohara M, Ogonuki N, Inoue K, Miki H, Ogura A, Toyokuni S, Shinohara T. Long-term proliferation in culture and germline transmission of mouse male germline stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:612–616. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.017012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Growth factors essential for self-renewal and expansion of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16489–16494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent S, Segretain D, Nishikawa S, Nishikawa SI, Sage J, Cuzin F, Rassoulzadegan M. Stage-specific expression of the Kit receptor and its ligand (KL) during male gametogenesis in the mouse: a Kit-KL interaction critical for meiosis. Development. 1998;125:4585–4593. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.22.4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kubota H, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Culture conditions and single growth factors affect fate determination of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:722–731. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.029207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellve AR, Cavicchia JC, Millette CF, O’Brien DA, Bhatnagar YM, Dym M. Spermatogenic cells of the prepuberal mouse. Isolation and morphological characterization. J Cell Biol. 1977;74:68–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.74.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Jonge HJ, Fehrmann RS, de Bont ES, Hofstra RM, Gerbens F, Kamps WA, de Vries EG, van der Zee AG, te Meerman GJ, ter Elst A. Evidence based selection of housekeeping genes. PLoS One. 2007;2:e898. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]