Summary

This study is concerned with the educational intervention layout proposed as a possible answer for the disparities in healthcare services for disabled persons.

Material and methods

The data sampling was performed on individuals in Rome, affected by psychophysical disabilities, living in residential care facilities. Participants were randomly divided into two groups: Study and Control Group, consisting of patients who did or did not participate in the Educational Phase. All the caregivers participated in an educational course. Screening period: September 2008 – March 2009. Examinations were performed using Visible Plaque Index (VPI), Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) and Microbiological Analysis.

Results

The total number of patients utilized for the study was 36 (18 in each group). The final sample amounted to 70% (14/20) in the Study Group and to 75% (15/20) in the Control Group. In both examined groups Oral Hygiene, Gingival Health State and Microbiological Analysis show an overall improvement of the indices, compared with the initial status, mostly at a follow-up after 4 weeks. However, Study Group show a significantly better improvement. Conversely, after 6 months the overall clinical indices worsened again.

Conclusion

The difference in the significant improvements of the groups, even if only over a short-time evaluation, endorses that the participation of the patients as well as tutors in the educational phase is an effective strategy for the short-term.

Keywords: oral health, oral diseases, disabilities, disabled patients

Background

The body of literature speaking to oral health (OH) initiatives throughout Europe is vast and often country specific. Sometimes this makes it difficult for policy makers and researchers alike to see the benefits of work done in one country applied to their own context. This is not so different from the experience in the United States where research done in each state has to take into consideration specific social and economic factors. Thanks to two important initiatives undertaken in this last decade, it has been possible to go beyond the differences, to construct a common framework and orientation for research in Oral Health everywhere in the world. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2), and the World Health Organization produced important guidelines, some of which he authors of this study used. They are as follows:

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Oral health is more than healthy teeth.

Oral diseases and disorders in and of themselves affect health and well-being throughout life.

The mouth reflects general health and well-being.

Oral diseases and conditions are associated with other health problems.

Safe and effective measures exist to prevent the most common dental diseases–dental caries and periodontal diseases.

WORLD HEATH ORGANIZATION

(available at http://www.who.int/oral_health/objectives/en/index.html)

Greater emphasis is put on developing global policies in oral health promotion and oral disease prevention

Oral health is part of total health and essential to quality of life…

There must be a priority given to integration of oral health with general health programs at community and national levels

Development of community empowerment strategies are essential. Over the last decades, there have been many significant studies documenting the inequities around the world between oral health care (OH) for individuals with disabilities and that provided for the general public. These studies have contributed to a more complete understanding of: 1) the OH diseases prevalent among disabled patients; 2) their possible causes; 3) possible discrepancies in care. The majority of data to date has indicated the following:

Disease profile of disabled patients: more frequent oral diseases among disabled patients are periodontal disease (3–7) and carious disease (8–9), but there are also cases of abnormal eruption and abnormal tooth development (10–14), diseases of the oral mucosa (5), changes in occlusion and masticatory function (5,10,15). For effective prevention and therapeutic interventions, studies have highlighted the need to consider patients’: type of disease, systemic status, and the specific needs that might arise due to the particular patient profile (13,14,19,25,30).

Possible causes of discrepancies in levels of care for disabled patients: many studies pointed to unequal access to care, which was tied to a host of underlying elements, including: economic factors, lack of information, physical/structural obstacles inherent to the institutions themselves, and inadequate preparation of health personnel (19,31,37).

Other factors contributing to a worse state of OH among disabled: low or absent self-sufficiency (16), pharmacological therapies (17,21) and particular systemic and oro-facial features (10,22,24).

Most of the studies concurred about the two primary areas of intervention: 1) Education: prescribing increased dissemination of information regarding OH (prevention and cure) to disabled patients and their caregivers: 2) Access to Services: proposing careful analysis of possible barriers (architectonic and cultural) to services for OH prevention and cure for disabled patients.

Aim of study

This study is concerned with the educational interventions proposed by many studies as a possible area of intervention for the disparities in healthcare services. Though they seemed to be pointing in a positive direction, few follow-up studies have been performed to evaluate these programs over the long-term. The aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of educational programs targeted to disabled patients and their tutors (or healthcare professionals who assist them) over time.

Materials and Methods

Population studied - sampling

The data sampling was performed on individuals in Rome, Italy, affected by psychophysical disabilities, living in residential care facilities with 24/7 professional assistance. In Italy, these particular structures providing care to disabled residents are called “Protected Residences” and are fully covered by the National Health Service.

The residences selected for this study are situated in the Municipality of Rome, Italy. They belong to the Association called “Coop. Soc. Progetto ‘96”, that has been working since 1999. They are part of a Protected Residential Project, which focuses on providing a positive and motivational environment to disabled individuals who can no longer live at home and have a tutor/patients ratio is 1/5.

The selection criterion for this study was age. All individuals older than 18 living in the above-mentioned residences were included (n = 40). No other inclusion or exclusion criteria was used. Participants were randomly divided into two groups: 1) Study Group, consisting of patients who participated in the educational phase regarding direct hygiene and oral health using didactic materials designed by the Dept. of Oral Health Science (Sapienza University, Rome). 2) Control Group, consisting of patients who did not participate in the Educational Phase. Each group was made up of 20 people.

Though the patients were of legal age, it was not possible for ethical reasons to construct a project whereby any of these patients would be studied without being accompanied by a tutor. Therefore, patient Tutors from both groups participated in the Educational Phase.

Screening period and data collection

Screening period: September 2008 – March 2009.

There were 3 sampling periods: T0, T1, T2.

T0 : first meeting for collection of data and educational encounters with patients and tutors.

T1 : Follow-up after 4 weeks

T2 : Follow-up after 6 months

The study was divided into two phases:

Phase 1 (T0): Educational encounters – duration 20 minutes; and collection of data regarding clinical and microbiological parameters

Phase 2 (T1, T2): Follow-up analysis of clinical and microbiological parameters at 4 weeks (T1) and 6 months (T2).

Examiners were trained on data collection and the taking of microbiological samples. Calibration included training sessions, actually data/sample collection, and a discussion/comparison of results. These sessions were comprised of a randomly selected group of 20 adult out-patients of the Oral and Maxillo-Facial Sciences Department of Sapienza University of Rome. They were divided into two groups of 10. The inter-examiner agreement was equal to 95%.

Intervention

T0 educational meetings with a duration of 20 minutes were organized for Study Group patients and for tutors of both groups (Study Group and Control Group). Audiovisual devices and models for simulation developed by a professor of Sapienza University, Rome were used. Then all patients underwent clinical examinations for the collection of data pertaining to the Visible Plaque Index (VPI) and Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) (Ainamo and Bay) (39).

Both clinical indices had Presence/Absence values and were chosen because of their optimal speed of execution and adaptability to a wide range of compliance levels among subjects.

The measurement of the Visible Plaque Index (VPI), expression of oral hygiene status, was based on the detection of the presence (positive value) of plaque clinically visible on the buccal, oral and interproximal surfaces of the teeth. The plaque had to be visible by all the examiners and by the patient being examined (optimally), in accordance with the recommendations of Ainamo and Bay (39).

The Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI), primary clinical expression of the gingival inflammation, was evaluated by detecting the presence or absence of bleeding after probing/pressing the examined gingival parts. A PDT Sensor® periodontal probe (probe made of plastic resin with high degree of flexibility and whose control device has probing force equal to 20 g) was placed into the gingival sulcus or periodontal pocket, parallel to the tooth’s long axis. The bleeding that appeared within 10 seconds was registered as positive value.

Furthermore, microbiological analysis was made, utilizing the Real-Time PCR (GABA International - meridol® Perio Diagnostics) (40), for the quantitative calculation of six bacteria which are markers of periodontitis and of total bacterial load. The bacterial strains identified which are markers for periodontitis were the following: Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythensis, Treponema denticola, Fusobacterium nucleatum ssp., Prevotella intermedia.

After sampling, the sub-gingival plaque samples were placed in into the pipettes provided and were sent in the original package for the Real-Time PCR analysis, according to the meridol® Perio Diagnostics protocol.

The results were obtained one week after the samples had been received by GABA meridol® Perio Diagnostics laboratory.

In Phase 2, all patients underwent the same clinical and microbiological exams according to the same parameters during the initial data collection Phase.

Data Analysis

The collected data were stored using the Microsoft Excel (Windows XP) program and the statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 10, 2000 (SPSS Software - Chicago).

The first step in the data analysis was a unvaried statistical processing, consisting of a descriptive analysis of data. The following step was the evaluation of the dependence between the considered variables, using Pearson Chi-square test. The comparison between the bacterial loads of the two groups was performed with the Mann-Whitney non-parametric test. As is standard, the level of significance for both tests was set equal to 0.05.

Results

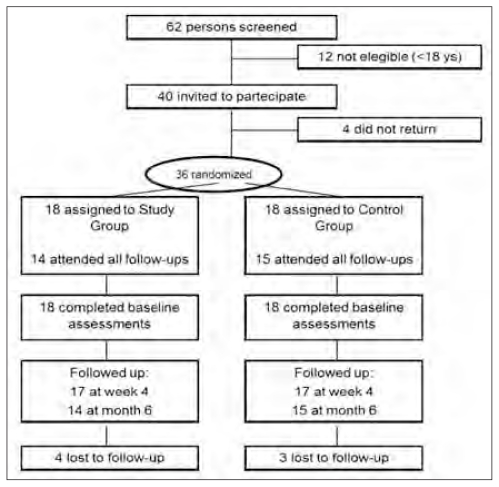

During the early phases of the project, two patients from each group were not compliant. Therefore, the total number of patients involved for the study was 36 (18 in each group). Also, due to personal problems, some patients were unable to participate in all tests. The final sample amounted to 70% (14/20) in the Study Group and to 75% (15/20) in the Control Group (Fig. 1). At T2, mean age in the Study Group was 31.9 years old, and in the Control Group was 41.6 years old. (Tab. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of participants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Final Sample (T2).

| n. | Male | Female | Average Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Group | 14 | 8 | 6 | 39.9 |

| Control Group | 15 | 9 | 6 | 41.6 |

| Total | 29 | 17 | 12 | 40.8 |

Oral Hygiene and Gingival Health

Tab. 2 - Shows the Visible Plaque Index (VPI) and the Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI) values for groups and phases.

Table 2.

Clinical Indices.

| Study Group | Control Group | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VPI + | |||

| T0 | 85.4% | 97.9% | - |

| T1 | 19.7% | 79.2% | 0.002 |

| T2 | 60.3% | 97.8% | 0.021 |

| GBI + | |||

| T0 | 80.5% | 87.5% | 0.614 |

| T1 | 28.9% | 45.8% | 0.410 |

| T2 | 70.7% | 86.7% | 0.360 |

Visible Plaque Index (VPI) results

T1: compared to the initial phase, the VPI values were lower at this phase, both in the Study Group and in the Control Group, with a significant difference between the two groups.

T2, the values of positive VPI are higher than T1, but lower than the values in the initial phase; also in this case there is a significant difference between the two groups.

Gingival Bleeding Index (GBI)

T1 this parameter shows a significant improvement only within groups.

Instead, at T2 the indices are similar to the values recorded at T0, especially in the Control Group; however, there was no significant difference in this phase between the two groups.

Microbiologic Analysis

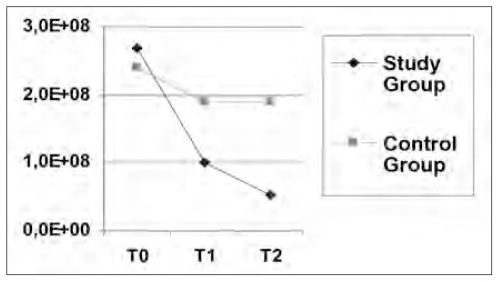

T1, the Real-Time PCR microbiological analysis showed an overall quantitative reduction of the total bacterial load in both groups.

At T2 the total bacterial load is further reduced in the Study Group and instead remains constant in the Control Group; in both cases the values show a significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2). Regarding bacteria marker (Tab. 3), the qualitative analysis showed at T1 a reduction of all the bacterial strains in both groups, except for the Fusobacterium nucleatum’s value, which shows a slight quantitative increase in the Control Group.

Figure 2.

Total bacterial load.

Table 3.

Marker bacteria.

| Study Group | Control Group | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans | |||

| T0 | 2.3×104/0.00 | 4.4×104/0.05 | 0.352/0.908 |

| T1 | 3.4×103/0.00 | 4.2×104/0.04 | 0.723/0.500 |

| T2 | 5.0×104/0.06 | 2.6×105/0.46 | 0.324/0.827 |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | |||

| T0 | 2.9×106/1.03 | 8.7×105/0.29 | 0.000/0.014 |

| T1 | 2.5×106/1.46 | 8.6×104/0.02 | 0.040/0.006 |

| T2 | 9.6×105/1.49 | 7.7×105/0.52 | 0.803/0.329 |

| Tannerella for sythensis | |||

| T0 | 4.2×106/2.05 | 1.9×106/0.81 | 0.050/0.096 |

| T1 | 9.8×105/1.06 | 1.7×106/0.81 | 0.931/0.308 |

| T2 | 7.0×105/1.22 | 3.5×106/1.55 | 0.160/0.692 |

| Treponema denticola | |||

| T0 | 6.8×106/2.86 | 5.2×106/1.75 | 0.217/0.267 |

| T1 | 2.1×106/2.16 | 2.3×106/1.03 | 0.890/0.201 |

| T2 | 9.8×105/1.36 | 8.3×106/3.21 | 0.173/0.400 |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | |||

| T0 | 2.6×106/1.02 | 3.7×105/0.23 | 0.076/0.046 |

| T1 | 3.5×105/0.72 | 4.6×105/0.23 | 0.642/0.092 |

| T2 | 6.0×105/1.26 | 1.6×105/0.25 | 0.518/0.095 |

| Prevotella intermedia | |||

| T0 | 8.3×106/2.01 | 2.3×106/1.05 | 0.073/0.136 |

| T1 | 4.2×106/2.76 | 1.1×106/0.50 | 0.015/0.004 |

| T2 | 1.2×106/3.30 | 2.9×106/0.98 | 0.066/0.015 |

At T2 the analysis indicates: (i) Study Group a reduction, compared with T1 of all the bacteria, except Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Fusobacterium nucleatum. Compared with T0 all the bacterial strains are reduced, except Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans; (ii) Control Group, compared with T1 all the bacterial markers are increased, except Fusobacterium nucleatum. Compared with T0 all the values are increased, except for Porphyromonas gengivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum.

Discussion

The analysis of the results of the examination of Oral Hygiene, Gingival Health State and Microbiological Analysis, shows an overall improvement of the indices, compared with the initial status, mostly at T1 in both examined groups.

STUDY GROUP (patients who participated in the educational phase of direct hygiene and oral health).

The results show that 4 weeks after the educational phase, the clinical and microbiological indices’ values decreased significantly in the Study Group patient. Conversely, after 6 months the overall clinical indices increased, although most microbiological values continued to decrease.

CONTROL GROUP (patients who did not attend the educational program).

In the Control Group, both clinical and microbiological values decreased after one month (even if less significantly than the first group) and returned to initial values after 6 months.

Therefore the most important observation concerns the clinical and qualitative/quantitative parameters of the oral bio-film: its clinical indices, its total load and its pathogen-periodontal bacteria decreased more in the Study Group than in the Control Group. This was the case in both follow up periods T1 and T2.

As a result, our data indicates that utilizing a structured educational program for disabled patients together with their tutors (i.e. caregivers) can improve both their oral health habits and the qualitative properties of bacterial plaque, reducing its pathogenicity over a brief period (4 weeks). The difference in the significant improvements of the groups, even if only over a short time, documents that the participation of the patient as well as caregivers/tutors in the educational phase is an effective strategy for the short-term.

Our data confirms the hypothesis put forth in much of the literature to date, which is that the active interest in disabled patients’ lives from people close to them, can positively affect their compliance. The fact that after 6 months the clinical indices in our study returned to the initial values in both groups, demonstrates a decreasing motivation and compliance over time. In patients this decreased motivation could be due to disability status itself and behavioural problems. Likewise, the tutors may be impacted by time-factor. For example, over a longer period, they may tend to underestimate the importance of oral prevention.

Our data clearly indicates that educational programs cannot be superficially evaluated without taking into consideration the time factor. As has been pointed out in many of the guidelines put forth in the global initiatives mentioned earlier, careful evaluation and monitoring over time are critical to the long-term success of any program.

Significant short-term improvements in OH after education of patients and tutors risk being examined too superficially. Our data indicate that improvements seen in the beginning period after a didactic/help session will not necessarily last. Our results indicate that over time – motivation, compliance, and disregard for the seriousness of OH, can all influence outcome as we observed after six months. The underestimation of the seriousness of Oral Health care among caregivers is understandable given the high number of health and behavioural issues that they encounter in this patient population. However, caregiver awareness of OH contribution to overall patient well-being is important and will hopefully be a focus for future studies. On-going review and follow-up, ideally at very short intervals could significantly improve long-term success, especially in this patient population where caregiver compliance is essential. Frequent motivating “alerts” (every month or maximum every two months) for the tutors have to be supported by easy access and low cost, as well as by a stimulating and innovative approach.

Many studies on disabled patient populations were done over the last two decades, prior to the development and/or widespread usage of new technologies for distance learning and digital communication. The results of this study could lead to the adoption of new educational channels that our colleagues hadn’t been able to consider.

The long-term decline in overall oral health indices (after 6 months) is greatly due to decreasing motivation over time. This can be conveniently and cost-effectively tackled by utilizing a vast array of new technological tools and digital media, which can be stimulating and more enjoyable for patients and their tutors. For example the internet, (e.mail/webinars/youtube) and even cell phones could be considered. Further studies should be done with these technological aids, in order to assess their efficacy in combating oral health worsening over the long-term, due to poor compliance and motivation.

References

- 1.Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; New York. 6 December 2006; [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.un.org/disabilities/convention/conventionfull.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. 2000. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/sgr/

- 3.Lancashire P, Janzen J, Zach GA, Addy M. The oral hygiene and gingival health of paraplegic inpatients--a cross-sectional survey. J Clin Periodontol. 1997 Mar;24(3):198–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucchese C, Checchi L. Lo stato orale in pazienti istituzionalizzati con ritardo mentale. Minerva Stomatol. 1998;47(10):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott A, March L, Stokes ML. A survey of oral health in a population of adults with developmental disabilities: Comparison with a national oral health survey of the general population. Aust Dent J. 1998;43(4):257–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1998.tb00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith DS. Health care management of adults with Down syndrome. [last access 18-03-2009];Am Fam Physician. 2001 64(6):1031–38. Available on http://www.aafp.org/afp/20010915/1031.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roizen NJ, Patterson D. Down’s syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361(9365):1281–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12987-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angelillo IF, Nobile CG, Pavia M, De Fazio P, Puca M, Amati A. Dental health and treatment needs in institutionalized psychiatric patients in Italy. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995;23(6):360–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain M, Marthur A, Kumar S, Dagli RJ, Duraiswamy P, Kulkarni S. Dentition status and treatment needs among children with impaired hearing attending a special school for the deaf and mute in Udaipur, India. J Oral Sci. 2008;50(2):161–5. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.50.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai SS. Down Syndrome: A Review of the Literature. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol, Oral Radiol, and Endod. 1997;84(3):279–85. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oredugba FA. Oral health condition and treatment needs of a group of Nigerian individuals with Down syndrome. [last access 18-03-2009];Down Syndr Res Pract. 2007 12(1):72–6. doi: 10.3104/reports.2022. Available on http://www.down-syndrome.org/reports/2022/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Oral Conditions in Children With Special Needs: A Guide for Health Care Providers. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Oral-HealthInformation/ChildrensOralHealth/OralConditionsChildrenSpecialNeeds.htm.

- 13.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Practical Oral Care for People With Intellectual Disability. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/PracticalOralCarePeopleIntellectualDisability.htm.

- 14.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Practical Oral Care for People With Down Syndrome. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/PracticalOralCarePeopleDownSyndrome.htm.

- 15.Hennequin M, Allison PJ, Veyrune JL. Prevalence of oral health problems in a group of individuals with Down Syndrome in France. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42(10):691–8. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200001274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Christensen GJ. Special oral hygiene and preventive care for special needs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(8):1141–3. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friedlander AH, Yagiela JA, Paterno VI, Mahler ME. The neuropathology, medical management and dental implications of autism. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(11):1517–27. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar M, Chandu GN, Shafiulla MD. Oral health status and treatment needs in institutionalized psychiatric patients: One year descriptive cross sectional study. [last access 18-03-2009];Indian J Dent Res. 2006 17(4):171–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29868. Available on http://www.ijdr.in/text.asp?2006/17/4/171/29868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stiefel DJ. Dental Care considerations for Disabled Adults. [last access 18-03-2009];Spec Care Dentist. 2002 22:26S–39S. Available on http://www.sc-donline.org/associations/2865/files/supplement.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mouradian WE, Corbin SB. Addressing Health Disparities Through Dental-Medical Collaborations, Part II. Cross-Cutting Themes in the Care of Special Populations. [last access 18-03-2009];J Dent Educ. 2003 67(12):1320–6. Available on http://www.jdentaled.org/cgi/reprint/67/12/1320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scorzetti L, Di Martino S, Marchetti E, Mummolo S, Fornarelli G, Marzo G. Ipertrofia gengivale secondaria all’assunzione di farmaci. Prima parte. Doctor Os. 2007;18(5):495–500. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pilcher ES. Dental Care for the Patient with Down Syndrome. [last access 18-03-2009];Down Syndr Res Pract. 1998 5(3):111–6. Available on http://www.down-syndrome.org/reviews/84/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desai SS, Flanagan TJ. Orthodontic Conditions in Individuals with Down Syndrome: A Case Report. Angle Orthod. 1999;69(1):85–8. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(1999)069<0085:OCIIWD>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennequin M, Faulks D, Veyrune JL, Bourdiol P. Significance of oral health in persons with Down Syndrome: a literature review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1999;41(4):275–83. doi: 10.1017/s0012162299000596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Continuing Education: Practical Oral Care for People With Developmental Disabilities. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/ContinuingEducation.htm.

- 26.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Practical Oral Care for People With Cerebral Palsy. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/PracticalOralCarePeopleCerebralPalsy.htm.

- 27.National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) Practical Oral Care for People With Autism. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/OralHealth/Topics/DevelopmentalDisabilities/PracticalOralCarePeopleAutism.htm.

- 28.Davies R, Bedi R, Scully C. ABC of oral health. Oral health care for patients with special needs. BMJ. 2000;321(7259):495–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7259.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawton L. Providing dental care for special patients. Tips for the general dentist. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133(12):1666–70. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berry AM, Davidson PM. Beyond comfort: Oral hygiene as a critical nursing activity in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2006;22(6):318–28. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.British Society for Disability and Oral Health (BSDH) Oral Health Care for People with Mental Health Problems. Guidelines and Recommendations. 2000. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.bsdh.org.uk/guidelines/mental.pdf.

- 32.British Society for Disability and Oral Health (BSDH) Guidelines for Oral Health Care for People with a Physical Disability. 2000. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.bsdh.org.uk/guidelines/physical.pdf.

- 33.Guay AH. Access to dental care. Solving the problem for under-served populations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135(11):1599–605. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pezzementi ML, Fisher MA. Oral health status of people with intellectual disabilities in the southeastern United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136(7):903–12. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fenton SJ, Hood H, Holder M, May PB, Mouradian WE. The American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry: Eliminating Health Disparities for Individuals with Mental Retardation and Other Developmental Disabilities. [last access 18-03-2009];J Dent Educ. 2003 67(12):1337–44. Available on http://www.jdentaled.org/cgi/reprint/67/12/1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Loeppky WP, Sigal MJ. Patients with Special Health Care Needs in General and Pediatric Dental Practices in Ontario. [last access 18-03-2009];J Can Dent Assoc. 2006 72(10):915. Available on http://www.cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-72/issue-10/915.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheller B. Systems issues workshop report. Pediatr Dent. 2007;29(2):150–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.D.P.C.M. 29 Novembre 2001(entrato in vigore il 23 febbraio 2002), mod. 28 Novembre 2003. “Definizione dei Livelli Essenziali di Assistenza”. [last access 18-03-2009]. Available on http://www.ministerosalute.it/program-mazione/lea/sezPrestazioni.jsp?id=149&label=lea02.

- 39.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals of recordig gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25(4):229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.GABAInternational. [last access 18-03-2009]. http://www.gaba.com/htm/568/en/meridol_Perio_Diagnostics.htm?Productgroup=MeridolPerioDiagnostics.