Abstract

Type 1 diabetes is preceded by islet β-cell dysfunction, but the mechanisms leading to β-cell dysfunction have not been rigorously studied. Because immune cell infiltration occurs prior to overt diabetes, we hypothesized that activation of inflammatory cascades and appearance of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in β-cells contributes to insulin secretory defects. Prediabetic nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice and control diabetes-resistant NOD-SCID and CD1 strains were studied for metabolic control and islet function and gene regulation. Prediabetic NOD mice were relatively glucose intolerant and had defective insulin secretion with elevated proinsulin:insulin ratios compared with control strains. Isolated islets from NOD mice displayed age-dependent increases in parameters of ER stress, morphologic alterations in ER structure by electron microscopy, and activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) target genes. Upon exposure to a mixture of proinflammatory cytokines that mimics the microenvironment of type 1 diabetes, MIN6 β-cells displayed evidence for polyribosomal runoff, a finding consistent with the translational initiation blockade characteristic of ER stress. We conclude that β-cells of prediabetic NOD mice display dysfunction and overt ER stress that may be driven by NF-κB signaling, and strategies that attenuate pathways leading to ER stress may preserve β-cell function in type 1 diabetes.

The pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes involves an orchestrated interplay between cell types of the immune system and the β-cell. In the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse, the prediabetic phase of the disease is characterized by infiltration of islets by macrophages and T cells, resulting in a scenario referred to as insulitis (1,2). Prior to overt β-cell death, it is thought that the local release of cytokines (interleukin 1β [IL-1β], γ-interferon [IFN-γ], and tumor necrosis factor-α [TNF-α]) by infiltrating cells activates inflammatory pathways in the β-cell leading to insulin deficiency and hyperglycemia (rev. in 3). It has been proposed that genetic and environmental factors might account for an increased susceptibility of β-cells both to attack by the immune system and to dysfunction in the face of an increasing inflammatory response (4). From this perspective, β-cells in the islet may be preferentially targeted in the setting of insulitis and thus contribute to their own demise. Early work described alterations in glucose homeostasis in NOD mice that were accompanied by defects in insulin secretion, even prior to the onset of diabetes (5,6). In human clinical trials, islet cell antibody-positive relatives of individuals with type 1 diabetes demonstrate defects in glucose tolerance and first-phase insulin release (7,8), suggesting that defects in β-cell function may precede the clinical onset of type 1 diabetes. Similarly, studies in NOD mice suggest that defects in first-phase insulin release may be an early sign portending diabetes (9,10). Despite evidence supporting early β-cell dysfunction in prediabetic humans and mice, the etiology underlying this dysfunction has remained largely speculative.

Proinflammatory cytokines are obvious candidates for precipitating early β-cell dysfunction. From studies of cell lines and isolated islets in vitro, cytokine signaling leads to the production of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in the short term (hours) and to activation of the unfolded protein response and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in the longer term (days) (11–13). Whether the development of ER stress is directly attributable to nitric oxide accumulation itself or secondarily to other cytokine-derived signals remains arguable. Nonetheless, it has been proposed that ER stress may contribute to the susceptibility of β-cells to dysfunction in NOD mice (4,14). In this study, we examined glycemic control and islet β-cell gene and protein expression patterns in the prediabetic phase of NOD mice, and compared these findings to those seen in NOD-SCID mice (a nondiabetic strain on the NOD background) and CD1 mice (an outbred nondiabetic strain). Our results indicate for the first time that islets from NOD mice exhibit progressive activation of the unfolded protein response at early ages (6 and 8 weeks), leading to decompensated ER stress at a later age (10 weeks). The striking upregulation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) target genes in 10-week-old NOD islets suggests that insulitis in NOD mice promotes an intracellular cascade that links NF-κB activation and ER stress to islet dysfunction.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

Female NOD/ShiLTJ (NOD) and age-matched female NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J (NOD-SCID) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). CD1 mice were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). All mice were maintained under protocols approved by the Indiana University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Diabetes was classified as two consecutive blood glucose levels above 300 mg/dL. Mouse islets were isolated from collagenase-perfused pancreata using a combination of purified collagenase (CIzyme MA; VitaCyte, Indianapolis, IN) and neutral protease (CIzyme BP Protease; VitaCyte). Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) studies using isolated islets were performed as previously described (15). Glucose tolerance tests in mice were performed using 2 g/kg glucose injected intraperitoneally (16). Serum insulin was measured using an Ultra Sensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL). Serum proinsulin was measured using a Proinsulin Rat/Mouse ELISA kit (Mercodia, Winston Salem, NC).

Real-time RT-PCR.

Reverse-transcribed islet RNA was analyzed by real-time PCR using SYBR Green or Taqman technology. Primers described previously include Ins-1/2 and pre-Ins2 (17); Bip, Xbp1, Xbp1s, and Chop (18); Serca2b (19); Atf4 and Wfs1 (20); and Pdx1 (16). For amplification of Cd3g, the following primers were used: 5′-TCAGTCAAGCCACAAGTCAGA- 3′ (forward) and 5′-ATGGAGCAGAGGAAGGGTCT-3′ (reverse). For Nos2, the following primers were used: 5′-CCTACCAAAGTGACCTGAAAGAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ATTCTGTGCTGTCCCAGTGAGGAG-3′ (reverse). Taqman Primers for Myd88, Tlr4, Il1b, Ifng, Nfkb1, and Irf1 were obtained from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). All samples were corrected for input RNA by normalizing to Actb message. All data represent the average of independent determinations from pooled islets from at least three separate isolations.

Immunoblots, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy.

Immunoblots were performed as described previously (21). For immunofluorescence experiments, pancreata were fixed and sectioned (16), and sections were stained using rabbit anti-mouse C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) (sc-575, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and mouse anti-mouse insulin (sc-8033, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-mouse were used for secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Images were acquired using an LSM 700 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). For electron microscopy, pancreata from each of three NOD and NOD-SCID mice were isolated following heart perfusion with a combination of paraformaldehyde and glutaraldehyde as previously described (20). Transmission electron micrographs were obtained at the Purdue University Life Science Microscopy Facility.

Polyribosomal profiling and 35S uptake assays.

For polyribosomal profiling studies (22), MIN6 β-cells were untreated or treated with 1 μmol/L thapsigargin for 6 h or a mixture of cytokines (10 ng/mL TNF-α, 100 ng/mL IFN-γ, 5 ng/mL IL-1β) ± 1 mmol/L aminoguanidine or 100 μmol/L NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA) for 24, 48, or 72 h. At the end of the incubation, cells were lysed and centrifuged, and the resulting supernatants were layered on a 10–50% sucrose gradient and centrifuged in an ultracentrifuge at 40,000 rpm for 2 h. A piston gradient fractionator (BioComp Instruments, Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada) was used to fractionate the gradients, and absorbance of RNA at 254 nm was recorded using an in-line ultraviolet monitor. For 35S uptake assays, MIN6 cells were cultured in 6-well plates in the presence or absence of cytokines for 24 or 72 h, then 100 μCi of a mixture of 35S-Met and 35S-Cys was added for 1 h. The cells were then lysed in SDS loading buffer. A fraction of the lysate was counted on a scintillation counter to correct for 35S amino acid uptake, and corrected lysate volumes were loaded on a 4–20% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and subjected to electrophoresis. The gel was dried and exposed to X-ray film overnight.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA (with Bonferroni post-test) was used for comparisons involving more than two conditions, and a two-tailed Student t test was used for comparisons involving two conditions. Prism 5 software was used for all statistical analyses. Statistical significance was assumed at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Prediabetic NOD mice exhibit progressive β-cell loss, dysfunction, and glucose intolerance with age.

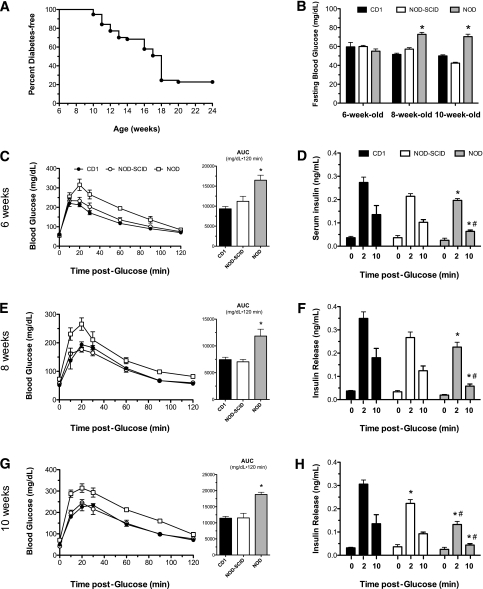

Female NOD mice housed in our vivarium facilities exhibited spontaneous conversion to diabetes after 10 weeks of age, with a cumulative incidence of diabetes of 78% by 20 weeks of age (Fig. 1A). Prior studies demonstrated that NOD mice exhibit early glucose intolerance that may be attributable to first-phase insulin deficiency (10). To assess glucose homeostasis and β-cell function in the prediabetic phase in this study, female NOD mice were subjected to glucose tolerance testing and serum insulin levels at 6, 8, and 10 weeks of age. NOD mice were compared with age-matched immune-deficient female mice on the NOD background (NOD-SCID) and to outbred immune-competent female mice (CD1), neither of which spontaneously develop diabetes. As shown in Fig. 1B, NOD mice show higher fasting glucose levels at 8 and 10 weeks compared with the diabetes-resistant strains, although these glucose values do not approach diabetic levels. Whereas glucose tolerance tests revealed no differences between NOD-SCID and CD1 mice at any of the ages (based on their corresponding area under the curve analyses), NOD mice showed relative and significant glucose intolerance at all ages, suggesting a subtle alteration in glucose homeostasis in prediabetic NOD mice (Fig. 1C, E, and G). To verify that this alteration in glucose homeostasis results from defects in insulin secretion, we measured serum insulin levels in response to an intraperitoneal load of glucose. As shown in Fig. 1D, F, and H, NOD mice displayed significantly reduced serum insulin levels at 2 and 10 min following an intraperitoneal glucose load at all ages compared with CD1 mice, consistent with prior studies that indicated a first-phase insulin secretory defect (10). Importantly, NOD-SCID mice showed no significant differences in insulin secretion compared with CD1 mice at 6 and 8 weeks of age, but showed a reduced 2-min insulin response at 10 weeks of age.

FIG. 1.

Glucose homeostasis in female CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice. A: Diabetes incidence in female NOD mice by age. Diabetes was defined as blood glucose >300 mg/dL on two consecutive measurements. n = 57 mice. B: Blood glucose values, as measured following an overnight fast in 6-, 8-, and 10-week-old mice. C, E, and G: Results of glucose tolerance tests and their corresponding area under the curve (AUC) analyses in mice at 6 (C), 8 (E), and 10 (G) weeks of age following intraperitoneal injections of glucose (2 mg/kg). n = 5–6 mice per group. D, F, and H: Serum insulin values in mice at 6 (D), 8 (F), and 10 (H) weeks of age at the indicated times following an intraperitoneal injection of glucose (2 g/kg). n = 3–4 mice per group. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding time value for CD1 mice. #P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding time value for NOD-SCID mice.

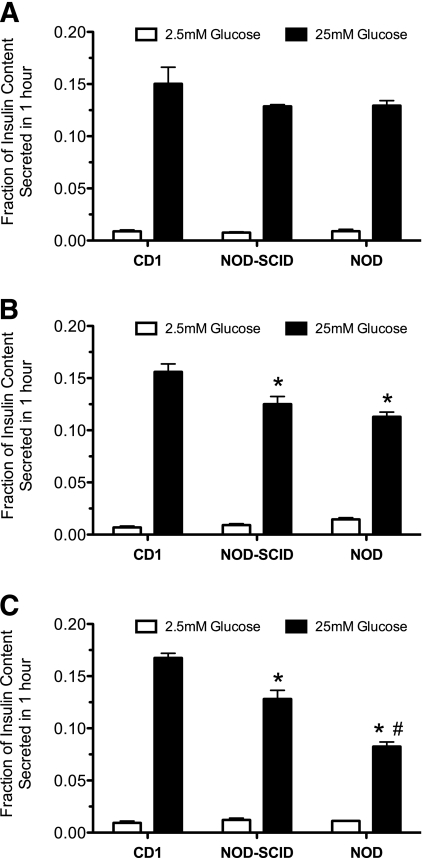

To clarify whether the apparent defect in glucose homeostasis in prediabetic NOD mice is attributable to β-cell dysfunction, we performed analysis of insulin secretion from isolated islets. Figure 2A–C shows that isolated islets from all ages of CD1 mice showed robust GSIS in static secretion assays, with insulin secretion at high glucose (25 mmol/L) that was at least 20-fold greater than at low glucose (2.5 mmol/L). Notably, both NOD-SCID and NOD islets from 8- and 10-week-old animals showed significantly reduced GSIS compared with CD1 islets, with NOD islets showing a progressively worse response at 10 weeks. Taken together, the data in Figs. 1 and 2 suggest that NOD mice exhibit reductions in insulin secretion and islet GSIS with time during the prediabetic phase, whereas NOD-SCID mice show milder losses but without apparent defects in glucose homeostasis.

FIG. 2.

GSIS from islets of female CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice. Shown are results of GSIS studies from islets of female CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice at 6 (A), 8 (B), and 10 (C) weeks of age exposed to low (2.5 mmol/L) and high (25 mmol/L) glucose concentrations. n = 3 independent, pooled islet isolations per group. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding glucose value for CD1 mice. #P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding glucose value for NOD-SCID mice.

Islets of prediabetic NOD mice exhibit early insulitis, loss of ER morphology, and ER stress.

The finding of early glucose intolerance and β-cell dysfunction led us to consider possible pathways that might contribute to defects in insulin secretion. Islets from 10-week-old NOD mice showed greater frequency and severity of cellular infiltration compared with islets from 6-week-old mice, as shown in the histology and scoring data in Supplementary Fig. 1A and B. This increase in insulitis with age suggests that proinflammatory cytokines secreted locally by the invading immune cells may contribute to the β-cell dysfunction of NOD mice. From studies in vitro, chronic incubation of islets and β-cell lines with proinflammatory cytokines leads to the activation of the unfolded protein response and eventual ER stress (11,13), but whether this occurs in NOD islets is unknown. To test for incident ER stress in islets of NOD mice, we first measured insulin and proinsulin levels in the serum of random-fed NOD, NOD-SCID, and CD1 mice. As shown in Fig. 3A, NOD mice exhibited a lower and progressively decreasing insulin level in serum with age compared with CD1 and NOD-SCID mice. However, the proinsulin level in NOD mice showed the opposite trend, with levels of proinsulin at 10 weeks that were 3-fold higher compared with NOD-SCID and CD1 mice (Fig. 3B). The ratio of proinsulin:insulin (Fig. 3C) was elevated a striking 9- and 16-fold, respectively, compared with CD1 and NOD-SCID mice at 10 weeks of age, a finding suggestive of an ER folding/processing defect. In this respect, prior electron microscopic studies suggested that NOD β-cells exhibit morphological alterations in the ER (6). To evaluate ER morphology in NOD mice compared with NOD-SCID mice, we performed transmission electron microscopy. As shown in the representative images in Fig. 3D, β-cells of NOD mice displayed fewer secretory granules and more swollen and fragmented ER compared with NOD-SCID mice, with loss of the neatly aligned stacks of ER adjacent to the nuclear membrane.

FIG. 3.

Secreted hormone levels and electron microscopic imaging of female prediabetic mice. A: Insulin levels in nonfasting 6-, 8-, and 10-week-old female CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice. B: Proinsulin levels in nonfasting 6-, 8-, and 10-week-old CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice. C: Proinsulin:insulin ratios in nonfasting 6-, 8-, and 10-week-old CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice. D: Representative low- and high-magnification transmission electron microscopic images of β-cells from 10-week-old NOD-SCID and prediabetic NOD mice. Arrows indicate ER. N, nucleus; SG, secretory granule. n = 4–5 mice in panels A–C. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding value for CD1 mice. #P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding value for NOD-SCID mice.

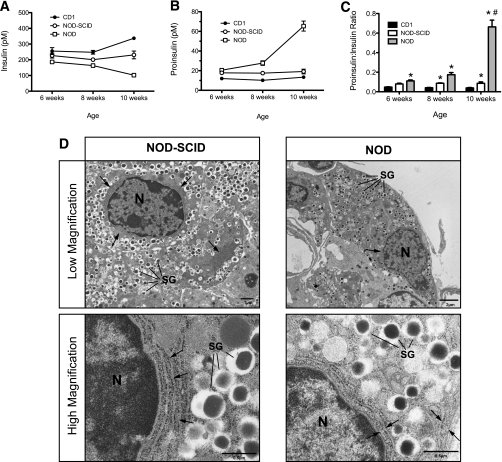

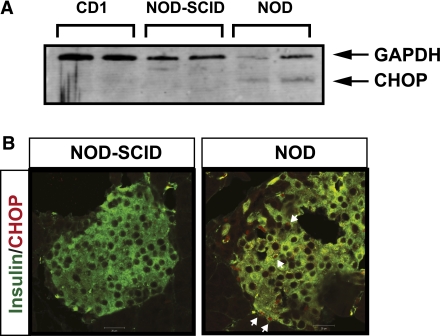

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms contributing to ER dysfunction, we isolated islets and performed real-time RT-PCR and immunoblots. To exclude the possibility that excessive infiltration by T cells was superseding the signals attributable to β-cells in NOD mice, we performed RT-PCR for the T cell gene Cd3g (CD3-γ chain) and found that its message levels represented <5% of Ins1/2 message in islets from NOD mice (Supplementary Fig. 2A and B). As shown in Fig. 4A and B, islets from 6-, 8-, and 10-week-old NOD mice demonstrated progressive reductions to more than 10-fold in the mRNAs encoding Pdx1 (Pdx1) and preproinsulin (Ins1/2). Interestingly, the pre-mRNA encoding preproinsulin (pre-Ins2, a species that more closely reflects acute changes in transcription of the gene encoding preproinsulin [17,23]) was elevated 3-fold above levels seen in CD1 mice at 6 weeks of age, but by 10 weeks a dramatic decrease of greater than 10-fold was observed (Fig. 4C). These findings suggest that at 6 (and perhaps 8) weeks of age, islets from NOD mice may be in a partial compensatory state that appears to be unsustainable by 10 weeks of age. Next, we examined the progression of ER stress markers in isolated islets over the same period of time. Islets from NOD mice showed elevations in the mRNA encoding the protein folding chaperone BIP (Bip) compared with NOD-SCID and CD1 mice (Fig. 4D). Whereas total Xbp1 mRNA was only slightly elevated in NOD mice, spliced Xbp1 mRNA (Xbp1s, an mRNA species that directly reflects ER stress activation via IRE-1α [24,25]). was significantly elevated at all ages, increasing by over 20-fold compared with the diabetes-resistant strains at 10 weeks of age (Fig. 4E and F). Accompanying the increase in Bip and Xbp1s mRNAs was a 10-fold increase in Chop mRNA by 10 weeks of age (Fig. 4G). Immunoblot analysis of islet extracts at 10 weeks of age revealed the presence of CHOP in islets from NOD animals, but not from diabetes-resistant strains (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B shows the localization of CHOP protein within the nuclei of insulin+ cells in a representative 10-week-old NOD mouse islet, whereas no CHOP staining was visible in a representative NOD-SCID islet.

FIG. 4.

Transcript levels of ER stress–responsive genes in islets of female CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice. Islets from 6-, 8-, and 10-week-old female CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice were isolated and processed for total RNA. Total RNA from each age and strain was then subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR for selected genes; the values were corrected for Actb mRNA levels and are displayed relative to 6-week-old CD1 islet data. Shown are results for Pdx1 (A), Ins1/2 (B), pre-Ins2 (C), Bip (D), Xbp1 (E), Xbp1s (F), Chop (G), Atf4 (H), Wfs1 (I), and Serca2b (J). n = 3 independent, pooled islet isolations per group. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding value for CD1 mice. #P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding value for NOD-SCID mice.

FIG. 5.

CHOP expression in islets and pancreata of prediabetic NOD mice. A: Results of immunoblot analysis for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and CHOP from islet extracts from each of two 10-week-old female CD1, NOD-SCID, and prediabetic NOD mice. B: Fixed pancreatic sections from 10-week-old female NOD-SCID and prediabetic NOD mice were subjected to immunofluorescence staining for insulin (green) and CHOP (red). Shown are representative islets from each strain. Arrows in the right panel identify CHOP+/insulin+ cells. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Islets of NOD mice fail to activate or maintain ER stress–remediating genes.

From prior studies by Stoffers and colleagues (20), it was suggested that the inability of Pdx1+/− mice to appropriately compensate for ER stress arises, in part, from inadequate activation (by Pdx1) of the stress response genes Atf4 and Wfs1. Atf4 encodes a transcription factor that is necessary for the activation of stress-related genes involved in the protection against oxidative stress (26), and Wfs1 encodes a protein that may be involved in the regulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis and granule acidification (27–29). As shown in Fig. 4H, Atf4 mRNA levels not only fail to activate with age (and increasing ER stress) in NOD mice, but remain significantly lower than in CD1 and NOD-SCID mice. Interestingly, although Wfs1 mRNA levels are elevated almost 6-fold in 6 week-old NOD mice, they rapidly fall by 8 weeks and remain significantly lower than in nondiabetic strains at 10 weeks (Fig. 4I). The mRNA level encoding another ER-associated Ca2+ transporter, Serca2b, is also observed to fall precipitously by 10-fold in 10 week-old NOD islets (Fig. 4J).

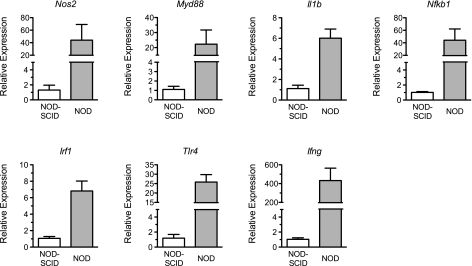

The NF-κB pathway is activated in NOD islets.

The NF-κB pathway is activated under a variety of cellular stressors, including proinflammatory cytokines and ER stress, to promote the host cell inflammatory response. To determine if NF-κB signaling is activated in prediabetic NOD islets, we performed real-time RT-PCR for a subset of NF-κB target genes. As shown in Fig. 6, striking and uniform activation (6–400-fold) of NF-κB targets Nos2, Myd88, Il1b, Nfkb1, Irf1, Tlr4, and Ifng were observed in prediabetic 10-week-old NOD islets compared with age-matched NOD-SCID islets. These data suggest the occurrence of an intracellular crosstalk between cytokine signaling, ER stress, and inflammation that may serve to promote the dysfunction or death of β-cells in NOD mice.

FIG. 6.

Transcript levels of NF-κB target genes in islets of female NOD-SCID and prediabetic NOD mice. Islets from 10-week-old female NOD-SCID and prediabetic NOD mice were isolated and processed for total RNA. Total RNA from each strain was then subjected to quantitative real-time RT-PCR for the NF-κB target genes shown at the top of each panel; the values were corrected for Actb mRNA levels and are displayed relative to NOD-SCID islet data. n = 3 independent, pooled islet isolations per group.

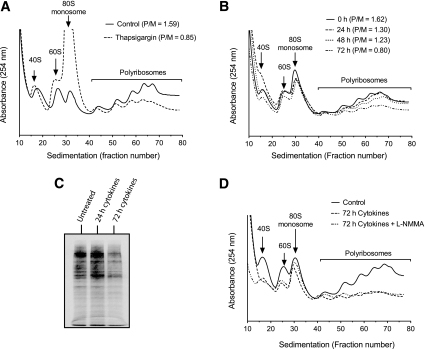

Cytokine milieu of type 1 diabetes induces an apparent block in translational initiation.

ER stress triggers the protein kinase regulated by RNA/ER–like kinase (PERK)-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2-α (eIF2-α); phospho-eIF2-α causes a block in the translational initiation of most cellular mRNAs in an attempt to decrease ER protein load (30,31). We asked whether exposure of cells to cytokines causes a translational initiation block, consistent with the ER stress response. To assess the translational effects directly, we performed sucrose gradient sedimentation of total RNA from MIN6 β-cells, followed by monitoring of ultraviolet absorbance through the gradient at 254 nm—a technique known as polyribosomal profiling (32). Figure 7A shows the position of the 80S ribosomal species as well as of polyribosomes (which contain multiple ribosomes bound to individual transcripts) from the RNA of control MIN6 cells. The ratio of polyribosomes to 80S monosomes (P/M ratio) is 1.59 in these control cells. A 6-h treatment of MIN6 cells with 1 μmol/L thapsigargin (a sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase [SERCA] pump inhibitor and inducer of ER stress) results in the dissipation of the polysome fraction and a decrease in the P/M ratio to 0.85, consistent with a block in initiation and a resultant runoff of polyribosomes (Fig. 7A). This ribosomal runoff and fall in the P/M ratio is considered a hallmark of a block in translational initiation (22). During a time course of treatment of MIN6 cells with cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) at 25 mmol/L glucose, there was a gradual loss of the polyribosomal fraction and a decrease in the P/M ratio that occurred after 24 h (Fig. 7B) (this decrease in P/M ratio occurred even in 5 mmol/L glucose, data not shown). To verify that this loss of polyribosomes resulted in a decrease in total protein synthesis, we incubated MIN6 cells with cytokines for varying times, then with a mixture of 35S-Met and 35S-Cys for 1 h. As shown in Fig. 7C, after loading correction for total cellular uptake of 35S, cytokine treatment resulted in a global decrease in total 35S incorporation into protein at 72 h. Because cytokines rapidly activate iNOS, we next asked whether inhibition of iNOS could prevent the initiation block upon prolonged cytokine incubation. Figure 7D shows that concurrent incubation of MIN6 cells with the nonspecific nitric oxide synthase inhibitor l-NMMA had no effect on initiation blockade after 72-h exposure to cytokines (identical data were obtained using a second, more selective iNOS inhibitor, aminoguanidine; data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Translational profiling of MIN6 cells. MIN6 cells were incubated with thapsigargin for 6 h or cytokines for the indicated times, then cellular extracts were harvested and subjected to centrifugation through a 10–50% sucrose gradient. Profiles through the gradient were measured by absorbance at 254 nm. A: Profiles of MIN6 cells untreated or exposed to thapsigargin. Positions of the 40S and 60S subunits, 80S monosome, and polyribosomes are indicated, and the P/M ratios are shown (as calculated from areas under the respective curves). B: Profiles of MIN6 cells untreated or exposed to a mixture of cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) for the indicated times are shown, as are the respective P/M ratios. C: Results of SDS-PAGE analysis of 35S-labeled protein in MIN6 cells that were untreated or exposed to cytokines for the indicated times. D: Profiles of MIN6 cells untreated and exposed to a mixture of cytokines or to a mixture of cytokines + 100 μmol/L l-NMMA. All data shown are from representative experiments performed on 2–3 occasions.

DISCUSSION

Islet β-cell dysfunction has long been thought to precede the development of type 1 diabetes. In both NOD mice and humans, loss of first-phase insulin secretion in response to a glucose load has been observed in the prediabetic period (7–9). Importantly, findings from the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial showed that individuals entering the study with residual β-cell function had lower rates of hypoglycemia and diabetic microvascular complications (33). Elucidating the underlying molecular pathways causing β-cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetes might suggest a therapeutic approach to preserving insulin secretion and thereby reducing diabetes complications. No clear mechanism linking immune cell infiltration and islet dysfunction has been definitively identified to date. In this study, we used a well-established mouse model of type 1 diabetes to demonstrate the activation of the NF-κB and ER stress pathways in β-cells of prediabetic NOD mice. The activation of these pathways may accelerate β-cell death in the prediabetic phase of the disease and thus promote further antigen exposure and T cell activation.

In autoimmune type 1 diabetes, the occurrence of β-cell ER stress has remained largely speculative. Given the striking insulitis seen in NOD mice, it is tempting to speculate a role for proinflammatory cytokines—released locally by invading macrophages and helper T cells—in initiating inflammation in the β-cell (via NF-κB) that eventually leads to the early defects in insulin secretion. The cross-talk between inflammation and ER stress has been the focus of several studies involving β-cell lines and islets, but has never been demonstrated in islets of NOD mice. We show here that NOD islets exhibit striking activation of both NF-κB signaling and ER stress pathways. However, it is difficult to know precisely whether NF-κB signaling leads to ER stress or vice-versa (34). Nevertheless, a hallmark of ER stress is the phosphorylation of the translational initiation factor eIF2-α (35), an event that is also seen upon the incubation of β-cell lines with IL-1β or a mixture of proinflammatory cytokines (36,37). Phosphorylation of eIF2-α blocks global translational initiation in an effort to mitigate ER protein load (31,35). In this study, we show for the first time by polyribosomal profiling analysis and 35S-Met/Cys uptake that MIN6 β-cells exhibit a decline in global translational initiation in response to chronic (days) exposure to proinflammatory cytokines, an effect that is similar to that observed following thapsigargin exposure.

Precisely how cytokines might cause ER stress is not clear, but some studies suggest that the nitric oxide generated via iNOS downregulates SERCA2B (11–13). SERCA2B is an ATP-dependent Ca2+ pump that is partially responsible for transport of Ca2+ into the ER lumen, thereby maintaining a steep ER:cytosolic Ca2+ gradient (19,38,39). Although our studies using iNOS inhibitors did not reverse the translational initiation blockade of prolonged cytokine exposure in vitro, they do not entirely rule out a contributory role for nitric oxide, as defects in the expression of other crucial ER proteins (e.g., Wfs1 and ATF4) and the confluence of other stress-induced proteins (e.g., NAPDH oxidase [40]) may contribute in the longer-term to translational blockade. ER stress has also been shown to activate NF-κB (34); thus, a self-perpetuating cascade may be occurring in prediabetic NOD β-cells that serves to promote defects in insulin secretion.

Prior studies have shown that β-cell mass is reduced (∼30%) in prediabetic NOD mice compared with NOD-SCID mice, suggesting that reductions in β-cell mass (independently of the defects in glucose-stimulated insulin release we have shown here) may also contribute to the relative glucose intolerance of prediabetic NOD mice (9). Our study does not address whether this reduction in β-cell mass in prediabetic NOD mice is a direct consequence of ER stress. Interestingly, a recent study by Satoh et al. (14) showed that global Chop deletion on the NOD background did not protect against β-cell loss or diabetes development. Moreover, studies using isolated rodent and human islets suggest that ER stress may not directly contribute to β-cell death, but rather to insulin secretory defects (11). In this respect, our results correlate the extent of ER stress with severity of β-cell secretory deficiency in prediabetic NOD mice.

Finally, a notable finding in our study is the reduction in Pdx1 mRNA and protein levels in 10-week-old NOD mice. Stoffers and colleagues (20) recently showed that Atf4 and Wfs1 are directly activated by Pdx1 in β-cells; both of these genes were reduced in our 8- and 10-week-old NOD animals. Hence, as in type 2 diabetes, Pdx1 levels may serve as a barometer of β-cell stress susceptibility in type 1 diabetes. Interestingly, Pdx1 mRNA levels were also reduced in NOD-SCID mice, which correlated with mild deficiencies in islet glucose responsiveness in vitro and elevated levels of Bip mRNA, Xbp1s mRNA, and serum proinsulin compared with CD1 mice. These findings may be referable to an inherent genetic feature of the NOD β-cell that enhances susceptibility to proinflammatory cytokines; indeed, although NOD-SCID mice have dysfunctional T and B cells, their intact macrophage activity and persistent TNF-α secretion (41) may contribute to mild β-cell dysfunction in these animals.

Our data support the conclusion that, independent of large reductions in β-cell mass, dysfunction of the islet β-cell precedes the onset of frank hyperglycemia in NOD mice. Although further studies are clearly warranted to clarify the precise contribution of the ER stress cascade to β-cell loss in type 1 diabetes, our studies suggest that approaches that reduce sources of ER stress or enhance the ability of the β-cell to intrinsically cope with ER stress may preserve β-cell function in the setting of autoimmunity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) (to R.G.M.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (Grant R01 DK083583 to R.G.M.), and the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (NIH Grant UL1 RR025761 to J.L.R.). S.M.C. is supported by an NIH training grant (T32 DK065549). Y.N. is supported by a Takeda-American Diabetes Association mentor-based postdoctoral award. A.T.T. is supported by an American Heart Association predoctoral award. S.C.C. is supported by a JDRF postdoctoral award.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

S.A.T. researched data and wrote the manuscript. Y.N., A.T.T., and S.M.C. researched data and reviewed the manuscript. N.D.S. and S.C.C. researched data. C.E.-M. and J.L.R. contributed to discussion and reviewed the manuscript. B.M. researched data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. R.G.M. conceived the experiments, researched data, and wrote the manuscript. S.A.T. and R.G.M. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors thank L. Narayanan (Indiana University) and B. Tersey (Indiana University) for their technical assistance. The authors also wish to acknowledge R. Wek (Indiana University) for helpful discussions; M. McDuffie (University of Virginia) for critically reading the manuscript; D. Sherman (Purdue University Life Science Microscopy Facility) for provision of electron microscopy images; and VitaCyte, LLC, for generously providing collagenase and neutral protease for islet isolations.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db11-1293/-/DC1.

See accompanying commentary, p. 780.

REFERENCES

- 1.Charré S, Rosmalen JG, Pelegri C, et al. Abnormalities in dendritic cell and macrophage accumulation in the pancreas of nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice during the early neonatal period. Histol Histopathol 2002;17:393–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDuffie M, Maybee NA, Keller SR, et al. Nonobese diabetic (NOD) mice congenic for a targeted deletion of 12/15-lipoxygenase are protected from autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes 2008;57:199–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehuen A, Diana J, Zaccone P, Cooke A. Immune cell crosstalk in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol 2010;10:501–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson MA, Bluestone JA, Eisenbarth GS, et al. How does type 1 diabetes develop?: the notion of homicide or β-cell suicide revisited. Diabetes 2011;60:1370–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strandell E, Eizirik DL, Sandler S. Reversal of beta-cell suppression in vitro in pancreatic islets isolated from nonobese diabetic mice during the phase preceding insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Invest 1990;85:1944–1950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leiter EH, Prochazka M, Coleman DL. The non-obese diabetic (NOD) mouse. Am J Pathol 1987;128:380–383 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keskinen P, Korhonen S, Kupila A, et al. First-phase insulin response in young healthy children at genetic and immunological risk for type I diabetes. Diabetologia 2002;45:1639–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrannini E, Mari A, Nofrate V, Sosenko JM, Skyler JS; DPT-1 Study Group Progression to diabetes in relatives of type 1 diabetic patients: mechanisms and mode of onset. Diabetes 2010;59:679–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sreenan S, Pick AJ, Levisetti M, Baldwin AC, Pugh W, Polonsky KS. Increased beta-cell proliferation and reduced mass before diabetes onset in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Diabetes 1999;48:989–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ize-Ludlow D, Lightfoot YL, Parker M, et al. Progressive erosion of β-cell function precedes the onset of hyperglycemia in the NOD mouse model of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 2011;60:2086–2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chambers KT, Unverferth JA, Weber SM, Wek RC, Urano F, Corbett JA. The role of nitric oxide and the unfolded protein response in cytokine-induced beta-cell death. Diabetes 2008;57:124–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyadomari S, Takeda K, Takiguchi M, et al. Nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in pancreatic beta cells is mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:10845–10850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardozo AK, Ortis F, Storling J, et al. Cytokines downregulate the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum pump Ca2+ ATPase 2b and deplete endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+, leading to induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 2005;54:452–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satoh T, Abiru N, Kobayashi M, et al. CHOP deletion does not impact the development of diabetes but suppresses the early production of insulin autoantibody in the NOD mouse. Apoptosis 2011;16:438–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maier B, Ogihara T, Trace AP, et al. The unique hypusine modification of eIF5A promotes islet beta cell inflammation and dysfunction in mice. J Clin Invest 2010;120:2156–2170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans-Molina C, Robbins RD, Kono T, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation restores islet function in diabetic mice through reduction of ER stress and maintenance of euchromatin structure. Mol Cell Biol 2009;29:2053–2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iype T, Francis J, Garmey JC, et al. Mechanism of insulin gene regulation by the pancreatic transcription factor Pdx-1: application of pre-mRNA analysis and chromatin immunoprecipitation to assess formation of functional transcriptional complexes. J Biol Chem 2005;280:16798–16807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lipson KL, Fonseca SG, Ishigaki S, et al. Regulation of insulin biosynthesis in pancreatic beta cells by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein kinase IRE1. Cell Metab 2006;4:245–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kulkarni RN, Roper MG, Dahlgren G, et al. Islet secretory defect in insulin receptor substrate 1 null mice is linked with reduced calcium signaling and expression of sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA)-2b and -3. Diabetes 2004;53:1517–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sachdeva MM, Claiborn KC, Khoo C, et al. Pdx1 (MODY4) regulates pancreatic beta cell susceptibility to ER stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:19090–19095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robbins RD, Tersey SA, Ogihara T, et al. Inhibition of deoxyhypusine synthase enhances islet beta cell function and survival in the setting of endoplasmic reticulum stress and type 2 diabetes. J Biol Chem 2010;285:39943–39952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palam LR, Baird TD, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of eIF2 facilitates ribosomal bypass of an inhibitory upstream ORF to enhance CHOP translation. J Biol Chem 2011;286:10939–10949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans-Molina C, Garmey JC, Ketchum RJ, Brayman KL, Deng S, Mirmira RG. Glucose regulation of insulin gene transcription and pre-mRNA processing in human islets. Diabetes 2007;56:827–835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshida H, Matsui T, Yamamoto A, Okada T, Mori K. XBP1 mRNA is induced by ATF6 and spliced by IRE1 in response to ER stress to produce a highly active transcription factor. Cell 2001;107:881–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calfon M, Zeng H, Urano F, et al. IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 2002;415:92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8:519–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fonseca SG, Ishigaki S, Oslowski CM, et al. Wolfram syndrome 1 gene negatively regulates ER stress signaling in rodent and human cells. J Clin Invest 2010;120:744–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riggs AC, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Ohsugi M, et al. Mice conditionally lacking the Wolfram gene in pancreatic islet beta cells exhibit diabetes as a result of enhanced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis. Diabetologia 2005;48:2313–2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hatanaka M, Tanabe K, Yanai A, et al. Wolfram syndrome 1 gene (WFS1) product localizes to secretory granules and determines granule acidification in pancreatic beta-cells. Hum Mol Genet 2011;20:1274–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang HY, Wek RC. Phosphorylation of the alpha-subunit of the eukaryotic initiation factor-2 (eIF2alpha) reduces protein synthesis and enhances apoptosis in response to proteasome inhibition. J Biol Chem 2005;280:14189–14202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Back SH, Scheuner D, Han J, et al. Translation attenuation through eIF2alpha phosphorylation prevents oxidative stress and maintains the differentiated state in beta cells. Cell Metab 2009;10:13–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teske BF, Baird TD, Wek RC. Methods for analyzing eIF2 kinases and translational control in the unfolded protein response. Methods Enzymol 2011;490:333–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steffes MW, Sibley S, Jackson M, Thomas W. Beta-cell function and the development of diabetes-related complications in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care 2003;26:832–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell 2010;140:900–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wek RC, Jiang HY, Anthony TG. Coping with stress: eIF2 kinases and translational control. Biochem Soc Trans 2006;34:7–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pirot P, Ortis F, Cnop M, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress gene chop in pancreatic insulin-producing cells. Diabetes 2007;56:1069–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akerfeldt MC, Howes J, Chan JY, et al. Cytokine-induced beta-cell death is independent of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. Diabetes 2008;57:3034–3044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meldolesi J, Pozzan T. The endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store: a view from the lumen. Trends Biochem Sci 1998;23:10–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bygrave FL, Benedetti A. What is the concentration of calcium ions in the endoplasmic reticulum? Cell Calcium 1996;19:547–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Subasinghe W, Syed I, Kowluru A. Phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase promotes cytokine-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in pancreatic β-cells: evidence for regulation by Rac1. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011;300:R12–R20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dahlén E, Dawe K, Ohlsson L, Hedlund G. Dendritic cells and macrophages are the first and major producers of TNF-alpha in pancreatic islets in the nonobese diabetic mouse. J Immunol 1998;160:3585–3593 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.