Abstract

Recent studies reveal a strong relationship between reduced mitochondrial content and insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle, although the underlying factors responsible for this association remain unknown. To address this question, we analyzed muscle biopsy samples from young, lean, insulin resistant (IR) offspring of parents with type 2 diabetes and control subjects by microarray analyses and found significant differences in expression of ∼512 probe pairs. We then screened these genes for their potential involvement in the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis using RNA interference and found that mRNA and protein expression of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in skeletal muscle was significantly decreased in the IR offspring and was associated with decreased mitochondrial density. Furthermore, we show that LPL knockdown in muscle cells decreased mitochondrial content by effectively decreasing fatty acid delivery and subsequent activation of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR)-δ. Taken together, these data suggest that decreased mitochondrial content in muscle of IR offspring may be due in part to reductions in LPL expression in skeletal muscle resulting in decreased PPAR-δ activation.

Although reduced mitochondrial function, as a result of decreased mitochondrial content, is associated with increased intramyocellular lipid content and insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle (1–3), the underlying factors responsible for these changes remain unknown. Two previous microarray studies implicate downregulation of peroxisome proliferator activated–receptor (PPAR)-γ coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) responsive genes in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) (4,5) as being responsible for decreased mitochondrial biogenesis; however, these findings could not be replicated in lean, nondiabetic, insulin resistant (IR) offspring of parents with T2D (2).

To identify potential factors responsible for reduced mitochondrial content in IR offspring, we analyzed mRNA expression in skeletal muscle of young, lean IR offspring and control subjects using microarray analysis and found ∼512 probe pairs, which were significantly different between the IR offspring and the insulin-sensitive control subjects. Consistent with our previous studies, we found no differences in the expression of PGC-1α or gene sets regulated by PGC-1α using Gene Enrichment Set Analysis (5). However, we did observe significant reductions in the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in the IR offspring group (Supplementary Table 2). We therefore screened these 250 genes for their potential role in the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis by treating RC13 cells (human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line) with RNA interference (RNAi) reagents to knock down expression of these candidate genes and monitored mitochondrial content in these cells using a mitochondrial-specific dye. Using this approach, we identified reduced expression of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) as a potential factor that may be responsible in part for reduced muscle mitochondrial content in IR offspring.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

All subjects (N = 22) were recruited by means of local advertising and were prescreened to confirm that they were in excellent health, lean, nonsmoking, and taking no medications. A birth weight >2.3 kg and a sedentary lifestyle, as defined by an activity index questionnaire (6), were also required. Qualifying subjects underwent a 3-h oral glucose tolerance test (with a 75-g oral glucose load) with calculation of an insulin sensitivity index (ISI) (7), after which two subgroups of subjects were selected to identify extreme phenotypes for insulin resistance and increased insulin sensitivity.

The group of IR subjects (n = 11) had at least one parent or grandparent with T2D, at least one other family member with T2D, and an ISI of <4.0 (7). The insulin-sensitive control subjects (n = 11) were defined by an ISI >7.0 and without a family history of T2D. The groups were matched for age, weight, BMI, and activity.

Written consent was obtained from each subject after the purpose, nature, and potential complications of the studies had been explained. The protocol was approved by the Yale Human Investigation Committee.

Diet and study preparation.

Subjects were instructed to eat a regular, weight-maintenance diet containing at least 150 g carbohydrate and not to perform any exercise other than normal walking for the 3 days before the study. Subjects were admitted to the Yale–New Haven Hospital the evening before the study and fasted from 10 p.m. with free access to water until the completion of the study the following day.

Measurement of metabolites and hormones.

Plasma glucose concentrations were measured with a YSI 2700 Analyzer. Plasma concentrations of insulin were measured using a double-antibody radioimmunoassay kit.

Muscle biopsy.

The skin over the vastus lateralis muscle was sterilely prepared with betadine, and 1% lidocaine was injected subcutaneously. A 2-cm incision was made using a scalpel, and a baseline punch muscle biopsy was extracted using a 5-mm Bergstrom biopsy needle (Warsaw, IN). A piece of muscle tissue was dissected with a scalpel and immediately fixed in glutaraldehyde buffer for electron microscopy studies as described below. The remainder of the muscle tissue was blotted, snap frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen until assay.

Affymetrix microarray complementary RNA synthesis and labeling, hybridization, and expression profiling.

Total RNA was extracted from ∼60-mg skeletal muscle samples using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN). Double-stranded cDNA was synthesized from 6 μg total RNA using the SuperScript Choice system (Invitrogen) and the T7-Oligo (dT) promoter primer kit (Affymetrix). cDNA was purified using Phase Lock Gels (Eppendorf 5-prime) and used to synthesize biotin-labeled cRNA. Next, 15 μg biotin-labeled cRNA was hybridized onto Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 GeneChips (Affymetrix). Procedures for cRNA preparation and GeneChips processing were performed as previously described (8). In the first microarray, we analyzed muscle biopsies from six control subjects and five IR offspring, who participated in a previous study (2). In a second microarray study, we analyzed muscle biopsies from newly recruited subjects (n = 5 control subjects, n = 6 IR offspring) using 1 μg total RNA (Supplementary Table 1). In the second microarray analysis, six muscle biopsies from the first microarray study were included to double-check the results of the first microarray analysis.

Microarray data analysis.

Data analysis was performed using Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 software to generate an absolute analysis for each chip. Each chip was scaled globally to a target intensity value of 800 to allow for interarray comparisons. Gene expression values from MAS 5.0 were then imported into GeneSpring GX 7.3 for further analysis. We applied two-sample t test to compare the expression changes between insulin resistance and insulin sensitivity. The genes up- or downregulated >1.2-fold and P < 0.05 were used for hierarchical clustering analysis, gene ontology analysis, and pathway analysis. For screening with RNAi, fold change >2.0 and lower than −1.3 was considered significant. We also selected genes with a P value <0.01. In summary, we selected 250 out of 512 genes.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis.

Total RNA was isolated from each basal muscle section and culture cell lines using an RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was prepared from 1 μg RNA using the StrataScript RT-PCR kit (Stratagene) with random hexamer primers, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting cDNA was diluted and 5-ng aliquot was used in 50 μL PCR reaction using a TaqMan gene expression assay (Applied Biosystems). PCR reactions were run in duplicate and quantified with an ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detection System. Cycle threshold values were normalized to 18S ribosomal RNA expression, and results were expressed as a fold change of mRNA compared with insulin-sensitive control subjects.

Western blot assay.

Western blot was performed as described previously (9). In brief, samples were homogenized in lysis buffer containing 50 mmol/L HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mmol/L NaCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mmol/L sodium vanadate, 100 mmol/L NaF, 20 mmol/L sodium pyrophosphate, 20 μg/mL aprotinin, and 1 mmol/L phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Samples were denatured with Laemmli sample buffer for 5 min at 95°C and 40-μg samples were separated using 7.5–15% SDS gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.) and electrotransfered onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.). The membrane was probed with antibodies against pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) (1:3,000; Invitrogen), succinate dehydrogenase (SDHA) (1:5,000; Abcam), porin (1:3,000; Molecular Probes), cytochrome c (1:3,000; BD Pharmingen), manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) (1:5,000; Stressgen), and cytochrome c oxidase I (MTCOI) (1:2,000; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Equal protein loading was confirmed by reblotting of the membranes with either a goat polyclonal antibody to pan-actin (1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (1:5,000; Chemicon). Images were analyzed and quantified with Quantity One (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.) or Scion software.

Cell culture.

Human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RC13 (also known as SJ-RH30 or RMA 13 cells) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 in 50-mL flasks in a culture medium composed of RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS (Invitrogen) and 1 mmol/L glutamine (10).

L6 cells, which were provided by Dr. Amira Klip (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada), were grown and maintained in α-minimum Eagle’s medium (α-MEM) containing 50 units/mL penicillin, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 10% FCS in a 5% CO2 environment. The cells were reseeded in the appropriate culture dishes and after reaching subconfluency, the medium was changed to α-MEM containing 2% FCS. The medium was then changed every 2 days until the cells were fully differentiated, typically after 4 days.

RNAi.

Individual siGENOME SMARTpool RNA duplexes for 250 candidate genes, including LPL as well as siCONTROL nontargeting small interfering RNA 1, were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). We also purchased siGENOME SMARTpool RNA duplexes for CD36, PPAR-δ, PPAR-α, and PGC-1α from Dharmacon. RC13 and L6 myotubes were transfected with small interfering RNA (25–50 nmol/L) using DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon) for 2–4 days.

Mitochondrial density determined by fluorescence.

RC13 were spread in 96-well plates (Nunc, 96-well optical bottom plate #165305); treated with an RNAi reagent (Dharmacon) against negative controls (nontargeting, GAPDH, and siGLR fluorescently labeled control), positive control (PGC-1α), and candidate genes (50 nmol); and incubated for 48 h. Cells were fixed with 3.8% formaldehyde and treated with both Mitotracker Green (1:1,000; Molecular Probe) for 30 min and DAPI (1:1,000; Molecular Probe) for 30 min. Fluorescence was detected with a multiple fluorescence reader and the mitochondria-to-nuclear ratio was calculated. When the mitochondria-to-nuclear ratios deviated >20% from the control samples, the candidate genes were further analyzed by Western blotting to confirm change in mitochondrial protein expression.

Determination of mitochondrial activity by MTT assay.

RC13 and L6 were spread in 96-well plates and treated with RNAi reagent against either nontargeting or LPL. Two days after the RNAi treatment, the cells were incubated with dye-free medium and incubated for 2 h with 0.5 mg/mL 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) before 1-h lysis by addition of two volumes of 10% SDS in 0.01 mol/L HCl (Cell Proliferation Kit I [MTT], Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were shaken and then formazan dye produced by mitochondrial dehydrogenases was photometrically measured at 565 nm.

Fatty acid stock preparation.

Fatty acids were bound to fatty acid–free BSA as previously described (11) with minor modifications. Fatty acids (200 mmol/L in ethanol) were diluted 1:12 into 10% BSA. The fatty acid mixture was gently agitated at 37°C for 1 h. The control medium containing ethanol and BSA was prepared similarly. The stock solutions were stored at −20°C, and working solutions were prepared fresh by diluting stock solution in 2% FCS α-MEM.

Electron microscopy.

Individual skeletal muscle samples were prepared by immersion in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4°C overnight. The samples were then washed three times in 0.1 mol/L cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and postfixed for 1 h in 1% osmium tetroxide (EMbed-812 epoxy resin) in the same buffer at room temperature. After three washes in water, the samples were stained for 1 h at room temperature in 2% uranyl acetate, washed again in water, and dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol dilutions (50–100%). The samples were then embedded in EMbed. Ultrathin (60 nm) sections were cut using a Reichert Ultracut ultramicrotome, collected on formvar- and carbon-coated grids, stained with 2% uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and examined in a Philips 410 electron microscope. Only cross-sections of skeletal muscle were examined for quantification of mitochondrial density. For each individual muscle, 15 random pictures were taken at a magnification of ×7,100 and printed at a final magnification of ×18,250. The volume density of mitochondria was estimated using the point-counting method. The average volume density was calculated for each individual muscle sample and was used to calculate the average volume density for each treatment.

Oxygen consumption assay.

Basal oxygen consumption was measured as previously described (12). In brief, a Seahorse Bioscience XF24–3 Extracellular Flux Analyzer was used to measure the rate of O2 consumption of L6 cells cultured in a collagen I–coated XF24 V7 cell culture microplate (Seahorse Bioscience). L6 myoblasts were seeded in XF24-well microplates at 2.0 × 104 cells per well (area 0.32 cm2) in 100 μL growth medium and then incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 overnight. The following day, an additional 100 μL growth medium was added; 1 day later, the medium was replaced with fresh medium. The RNAi experiment was performed against PPAR-δ 48 h before measurements of oxygen consumption, and the eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) treatment was performed 48 before measuring oxygen consumption at 50 μmol/L.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using ANOVA and unpaired Student t test with JMP software (SAS Institute). Fisher exact t test was used in the microarray experiments, and Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for correlation analyses. All data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Microarray in the offspring of T2D parents and age-matched control subjects.

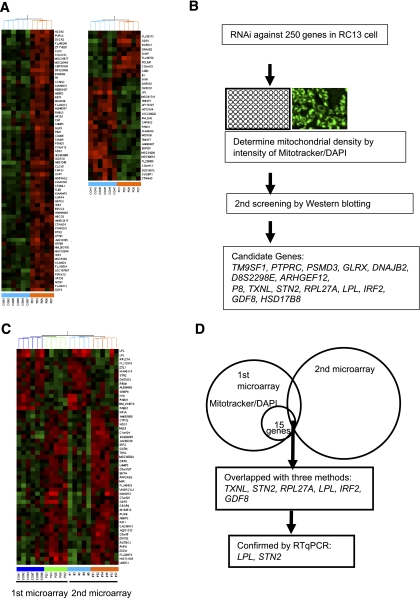

To assess gene expression in muscle of IR offspring, we purified mRNA in muscle biopsies taken from vastus lateralis muscles and then performed microarray data analysis using Human Genome U133 Affimatrix plus 2.0 GeneChip. Out of 53,947 probe pairs, 512 showed significant differences in expression compared with control subjects (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Consistent with our previous studies, we found no differences in the expression of PGC-1α or gene sets regulated by PGC-1α using Gene Enrichment Set Analysis (5). However, we did observe significant reductions in the expression of genes involved in mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in the IR offspring (Supplementary Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Microarray in the offspring of T2D parents and age-matched control subjects. A: Heat-map representations of genes detected in expression analysis of skeletal muscle of the offspring of T2D parents and age-matched control subjects. The list shows the top 100 genes by P value between two groups. B: Screening experiments using Mitotracker-to-DAPI ratio were performed after treatment with RNAi against 250 candidate genes in RC13 human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line. After the screening experiments, 45 genes were tested by Western blotting with MTCOI, PDH, and SDHA antibodies, and 15 genes showed significant change compared with treatment of nontargeting RNAi. C: Heat-map representations of overlapped genes in first microarray and second microarray. D: Six genes were overlapped with first microarray, second microarray, and former screening (B). A total of 2 out of 6 genes showed significant difference determined by RT-qPCR using TaqMan probe in control subjects (n = 7) and IR offspring (n = 13).

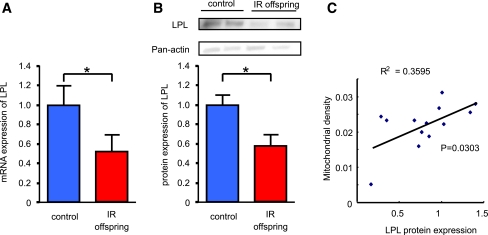

Most of the genes on the list were orphan; so to identify a potential new regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, we screened our genes with high throughput assays using cultured muscle cells by the ratio of mitochondrial- and nuclear-specific dye after RNAi treatment against the 250 candidate genes, which were selected based on stricter criteria. We therefore screened these 250 genes for their effect on mitochondrial density (mitochondria-to-nuclear ratio) and mitochondrial protein expression using Western blot against MTCOI, PDH, and SDHA. Out of these 250 candidate genes, we found 15 genes that changed mitochondrial density and mitochondrial protein expression (Fig. 1B). To confirm these observations in an independent group of young, lean IR offspring (n = 6) and an age/weight/BMI–matched group of insulin-sensitive control subjects (n = 5), we performed a second microarray study. In this study, two genes were consistently lower in the IR offspring compared with the insulin-sensitive control subjects; this finding was confirmed by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) (Fig. 1C and D). To further confirm these screening data using RNAi, we measured several mitochondrial proteins by Western blot and found that LPL was the most potent candidate protein to alter mitochondrial density under these experimental conditions. We confirmed the expression of LPL by RT-qPCR and Western blotting and found that expression of LPL mRNA and LPL protein were ∼45% reduced in the IR offspring as compared with the age/weight/BMI/activity–matched control subjects (Fig. 2A and B). Protein expression of LPL was positively correlated with mitochondrial density (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Lipoprotein lipase is decreased in skeletal muscle of young, lean IR offspring of T2D parents. A: mRNA expression of LPL determined by RT-qPCR using TaqMan probe in control subjects (n = 7) and IR offspring (n = 13). B: Protein expression of LPL measured by Western blotting in control subjects (n = 7) and IR offspring (n = 9). Results represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 vs. age/weight/BMI–matched healthy control subjects. C: Relationship between mitochondrial density measured by electron microscopy and LPL protein expression in skeletal muscle.

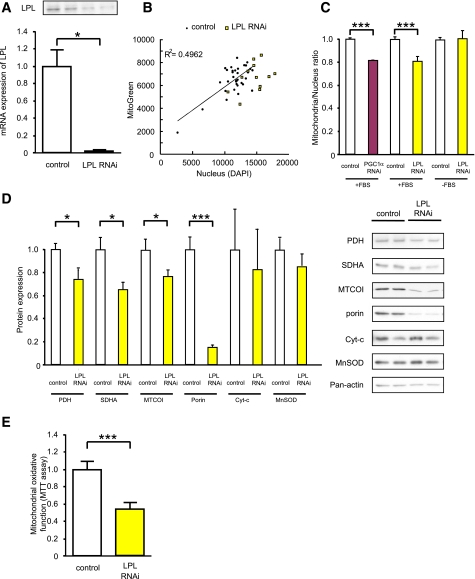

Suppression of the LPL gene by RNAi decreased mitochondrial density and protein expression in human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line RC13.

To test whether decreased expression of LPL can result in decreased mitochondrial density, we performed LPL knockdown by RNAi techniques in a human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (RC13). LPL RNAi treatment decreased LPL mRNA expression by ∼95% after 48 h of RNAi treatment (Fig. 3A). Under this condition, we analyzed mitochondrial density using mitochondrial-specific dye and found that depletion of LPL mRNA decreased mitochondrial density (Fig. 3B and C). This phenomenon was observed only when cells were treated with media containing FBS, the only source of fat for culture cells, or the VLDL fraction of human blood (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 1A).

FIG. 3.

LPL knockdown by RNAi in RC13 human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line. A: mRNA expression of LPL determined by RT-qPCR and Western blotting 72 h after RNAi treatment (50 μmol) in RC13. Represented LPL protein expression 48 h after RNAi treatment. B: Mitochondrial density measured by fluorescence dyes. RC13 cells were treated with RNAi reagents against either LPL or nontargeting control (50 nmol/L), maintained in 10% FBS RPMI for 48 h, fixed with 1% formaldehyde, stained with mitochondrial-specific Mitotracker Green (which stain mitochondria specifically), and scanned with multifluorescence reader. Nuclei were stained by DAPI. C: The intensity of Mitotracker dye was divided by DAPI signal to normalize cell number. RC13 cells were treated with LPL and PGC-1α RNAi reagent and maintained in either FBS-free RPMI or 10% FBS RPMI. D: Mitochondrial protein expression was determined by Western blotting 48 h after RNAi treatment (n = 8). Cyt-c, cytochrome c. E: MTT assay. RC13 cells were treated with LPL RNAi reagents (50 nmol/L) and maintained in 10% FBS RPMI for 48 h. Cells subsequently were incubated in phenol-red–free RPMI with and without MTT reagent (0.5 mg/mL) for 2 h, and mitochondrial oxidative activity was photometrically determined by measuring the formation of formazan from the MTT substrate (n = 16). Results represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0005 vs. nontargeting control.

Furthermore, we found that several mitochondrial proteins, such as MTCOI, PDH, and SDHA, which we have previously shown to be reduced in IR offspring were decreased by LPL RNAi treatment (Fig. 3D). There were no significant changes in expression of cytochrome c, somatic or MnSOD. We also observed a strong decrease in porin expression, the main pathway for transport of metabolites across the mitochondrial outer membrane (Fig. 3D). Finally, we analyzed mitochondrial oxidative function using MTT dye and found that LPL depletion reduced mitochondrial function in the RC13 cell line (Fig. 3E).

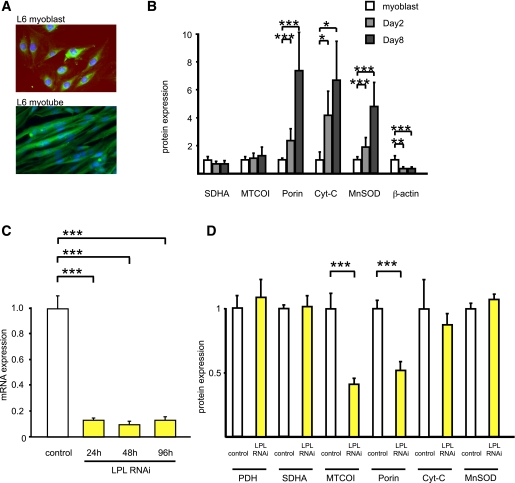

Suppression of LPL gene by RNAi decreased mitochondrial density and protein expression in L6 cell line.

To further evaluate the role of LPL in skeletal muscle, we analyzed LPL knockdown in L6 rat myotubes; in contrast to RC13, L6 differentiate into muscle fiber morphologically (Fig. 4A). The expression level of the mitochondrial proteins, such as porin, MnSOD, and cytochrome c, somatic, increased dramatically during L6 differentiation, but the others did not change (Fig. 4B). LPL RNAi treatment decreased LPL mRNA expression ∼90% at 24, 48, and 96 h posttransfection (Fig. 4C). In both RC13 and L6 myotubes, we found that depletion of LPL decreased the mitochondrial proteins MTCOI and porin (Fig. 4D) and mRNA of MTCOI (data not shown) without apparent morphological change and differentiation. Finally, LPL depletion reduced mitochondrial oxidative function as measured by MTT assay in L6 myotubes (0.63 ± 0.06 vs. 0.57 ± 0.05, P < 0.0005).

FIG. 4.

LPL knockdown by RNAi in rat L6 myotubes. A: Typical morphological change during differentiation. L6 myoblasts and L6 myotubes (4 days after, maintained with 2% α-MEM) were stained with Mitotracker Green and DAPI (magnification ×200). B: Mitochondrial protein expression during differentiation was determined by Western blotting at days 0, 2, and 8 in 2% FBS α-MEM (n = 3). Results represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005 vs. L6 myoblasts. C: mRNA expression of LPL determined by RT-qPCR at 24, 48, and 96 h after RNAi treatment (50 nmol/L, n = 6). Results represent mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.0005 vs. nontargeting controls. D: Mitochondrial protein expression of L6 myotubes (4 days in 2% FCS α-MEM) was assessed by Western blotting 48 h after RNAi treatment against either nontargeting control (n = 6) or LPL (n = 6). Results were normalized to GAPDH expression. Results represent mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.0005 vs. nontargeting controls. Cyt-c, cytochrome c. (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

Fatty acid flux regulates mitochondrial biogenesis in L6 myotubes.

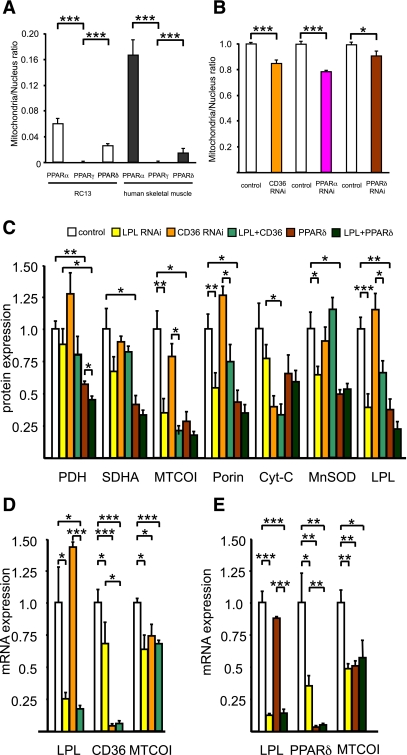

We hypothesized that fatty acid flux into the skeletal muscle regulates mitochondrial biogenesis through a PPAR-dependent process. To test this hypothesis, we first analyzed three PPAR genes by RT-qPCR to clarify which isoform is dominant in human skeletal muscle and found that both PPAR-α and PPAR-δ are dominant compared with the PPAR-γ isoforms, as previously reported (Fig. 5A) (13). We next knocked down PPAR-α and PPAR-δ in RC13 cells and measured mitochondrial density by mitochondrial-specific dye. As we expected, both PPAR-α and PPAR-δ RNAi decreased mitochondrial density (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Role of PPARs and CD36 in mitochondrial biogenesis. A: mRNA expression of PPAR isoforms determined by RT-qPCR using TaqMan probe in RC13 human rhabdomyosarcoma cell line (n = 4) and human skeletal muscle (n = 4). Data were normalized with 18S rRNA expression. B: RC13 cells were treated with CD36, PPAR-α, and PPAR-δ RNAi (50 nmol/L), maintained in 10% FBS RPMI for 48 h, fixed with 1% formaldehyde, stained with Mitotracker Green (which stain mitochondria specifically), and scanned with multifluorescence reader. The quantity of Mitotracker Green dye was divided by DAPI signal to normalize cell number. Results represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0005 vs. nontargeting control. C: Mitochondrial protein expressions in L6 myotubes measured by Western blotting in control (nontargeting control 50 nmol/L; n = 6), LPL RNAi (LPL RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 6), CD36 RNAi (CD36 RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3), combination of LPL and CD36 RNAi (LPL RNAi 25 nmol/L + CD36 RNAi 25 nmol/L; n = 3), PPAR-δ RNAi (PPAR-δ RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3), and combination of LPL and PPAR-δ RNAi (PPAR-δ RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3). Cyt-c, cytochrome c. D: mRNA expression of MTCOI determined by RT-qPCR in L6 myotubes after RNAi treatment against control (nontargeting control 50 nmol/L; n = 3), LPL RNAi (LPL RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3), and CD36 RNAi (CD36 RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3). E: mRNA expression of MTCOI determined by RT-qPCR in L6 myotubes after RNAi treatment against control (nontargeting control 50 nmol/L; n = 3), LPL RNAi (LPL RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3), PPAR-δ RNAi (PPAR-δ RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3), and combination of LPL and PPAR-δ RNAi (PPAR-δ RNAi 25 nmol/L + nontargeting control 25 nmol/L; n = 3). Results represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.0005.

To decrease fatty acid incorporation into the cell, we next knocked down CD36 (fatty acid translocase) by RNAi and found that this treatment decreased mitochondrial density by 17% (Fig. 5B). To confirm these data by protein expression level, we treated L6 myotubes with LPL, PPAR-δ, and CD36 RNAi and found that not only LPL RNAi but also both PPAR-δ and CD36 RNAi decreased mitochondrial protein expression (Fig. 5C). We also knocked down PPAR-α by RNAi but did not see the difference on the protein expression of MTCOI, SDHA, and PDH (data not shown). We used RT-qPCR to examine MTCOI mRNA expression and found that CD36 and PPAR-δ RNAi treatment decreased MTCOI mRNA expression (Fig. 5D and E). In contrast, fatty acid treatment increased several mitochondrial genes related to fatty acid oxidation and glucose metabolism. mRNA expression of CPT1b, UCP3, and PDK4 were significantly induced by EPA, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and bromopalmitate (a known PPAR activator), suggesting that fatty acid flux into the cell mediates fatty acid oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 2A–C).

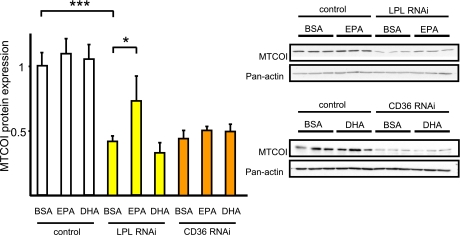

Next, we tested the effect of several fatty acids on the mitochondrial-to-nuclear ratio and found EPA to have the strongest effects (Supplementary Fig. 2D). We hypothesized that PUFA may be rescuing mitochondrial gene expression during the LPL RNAi treatment and found that indeed, EPA rescued MTCOI protein during LPL knockdown but that MTCOI protein expression did not change during CD36 knockdown (Fig. 6). GW501516, a PPAR-δ agonist, and PUFA stimulate mRNA expression of CPT1b, UCP3, and PDK4 (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3A–C). Thus, we tested GW501516 treatment on MTCOI protein expression during LPL knockdown and found a partial rescue of MTCOI protein expression after GW501516 treatment (Supplementary Fig. 3D).

FIG. 6.

EPA treatment rescued LPL RNAi–induced suppression of MTCOI protein expression. L6 myotubes were incubated with EPA (50 μmol/L), DHA (50 μmol/L), or 0.125% BSA for 48 h after LPL and CD36 RNAi treatment (50 nmol/L). MTCOI protein expressions were measured by Western blotting (n = 9). Results represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.0005.

DISCUSSION

Insulin resistance in skeletal muscle, as a result of decreased insulin-stimulated muscle glucose transport and muscle glycogen synthesis, is one of the earliest detected abnormalities in the pathogenesis of T2D (14–16). Previous studies show a strong relationship between increased intramyocellular lipid content and reduced insulin-stimulated muscle glucose uptake in both humans (14,17) and rodents (18–20), which has led to the hypothesis that an increase in intracellular lipid metabolites (e.g., diacylglycerol and ceramides), due to a mismatch between fatty acid delivery and mitochondrial oxidation or conversion to neutral lipid (triacylglycerol), leads to activation of novel and conventional protein kinase Cs (e.g., PKCθ, PKCδ, and PKCβ) that results in decreased insulin signaling and insulin action (2,19,21–23). In this regard, recent studies show an ∼35% reduction in resting muscle mitochondrial ATP production (3) and tricarboxylic acid activity (1) in young, lean IR offspring, which could be attributed to a 35% reduction in mitochondrial density (2). Taken together, these data suggest that reductions in mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle of IR offspring may be an important contributing factor that predisposes these individuals to intramyocellular lipid accumulation and muscle insulin resistance. To further examine the mechanism responsible for reduced muscle mitochondrial density in these individuals, we assessed gene expression in muscle by microarray analysis in a similar group of young, lean IR offspring and found that mRNA and protein expression of LPL were reduced by ∼45% compared with age/weight/BMI–matched control subjects. This observation is consistent with previous studies that observe lower skeletal muscle LPL activity in overweight and T2D subjects (24).

Previous studies show that insulin per se stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis (25,26) and that mitochondrial morphology is altered in obese IR and T2D individuals (27). It is therefore possible that insulin resistance is the cause and not the effect of reduced mitochondrial content in the IR offspring. Insulin has been shown to upregulate expression of LPL mRNA in adipose tissue and in postheparin plasma (28), but in contrast, insulin does not appear to activate LPL gene expression in skeletal muscle (29–31). To assess the potential role of LPL in the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis, we next investigated the effect of knocking down LPL gene expression by RNAi techniques and assessed mitochondrial density and mitochondrial protein expression. Using this approach, we found that knocking down LPL expression in both RC13 human rhabdomyosarcoma cells and L6 rat myotubes decreased mitochondrial density and protein expression as well as mitochondrial oxidative capacity. These observations are supported by previous studies that show increased mitochondria density and SDH activity in mice with overexpression of LPL in skeletal muscle (32).

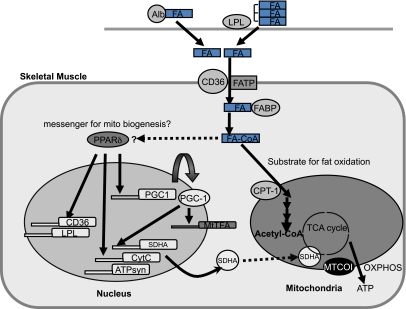

Given these findings, we examined the hypothesis that fatty acid flux into the myocyte, working through activation of PPARs, may be an important intracellular regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 7) (33,34). Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that RNAi treatment of CD36 (fatty acid translocase) partially decreased mitochondrial protein expression, indicating that fatty acid uptake into the cell may be an important factor regulating mitochondrial biogenesis.

FIG. 7.

Fatty acid flux into skeletal muscle, a potential intracellular regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis through activation of PPAR-δ. LPL hydrolyzes serum triglycerides (VLDL and chylomicrons) releasing fatty acids, which are subsequently internalized by the muscle cell. Fatty acids are also derived from adipose tissue lipolysis and bound to albumin, which is subsequently taken up via cell surface receptors such as fatty acid translocase/CD36, plasma membrane–bound fatty acid binding protein (FABP), and fatty acid transport protein (FATP). Once in the cytoplasm, long-chain fatty acids are bound to cytoplasmic FABP, and upon activation to acyl-CoA at the AMP-binding site of FATP, the formed acyl-CoA esters will bind to acyl-CoA–binding protein before being metabolized. Long-chain acyl-CoA are oxidized during β-oxidation in mitochondria after being converted to long-chain acylcarnitines catalyzed by CPT-1. We propose that muscle mitochondrial content is regulated in part by EPA-CoA activation of PPAR-δ. Alb, albumin; FA, fatty acid; MtTFA, mitochondrial transcription factor A; CytC, cytochrome c; ATPsyn, ATP synthase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid; OXPHOS, oxidative phosphorylation.

Both PPAR-α and PPAR-δ are highly expressed in skeletal muscle, and PPAR-δ activation has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity through increased fat oxidation and increased muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in rodents (35,36), although there was no significant difference in mRNA expression of PPAR-α and PPAR-δ between the IR offspring and control subjects (data not shown). In addition, polymorphisms in the PPAR-δ gene have been found to be associated with alterations in mitochondrial function, aerobic physical fitness, and insulin sensitivity in humans (37). Consistent with these findings, we found that knocking down PPAR-δ expression in L6 myotubes decreased mitochondrial density, mitochondrial protein expression, and oxygen consumption (Fig. 5B and C and Supplementary Fig. 3E). Previous studies show that unsaturated fatty acids increase PGC-1α expression in cultured muscle cells (38) and that PUFA increases mitochondrial biogenesis in liver (39) and white adipose tissue (40). We therefore examined the possible role of PUFAs as potential mediators of mitochondrial biogenesis in muscle cells and found that EPA, but not DHA, rescued decreased MTCOI protein expression by LPL knockdown in L6 myotubes, suggesting that EPA may be a key fatty acid mediator by which LPL expression regulates mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle.

In summary, these results provide new insights into the earliest abnormalities that may be responsible for the pathogenesis of muscle insulin resistance in T2D. Taken together, these data suggest that decreased mitochondrial content in muscle of IR offspring may be due in part to reductions in LPL expression in skeletal muscle, resulting in decreased PPAR-δ activation. Furthermore, these data support the hypothesis that EPA influx into skeletal muscle is a potential molecular signal that regulates mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle via activation of PPAR-δ.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. Public Health Service (R01-DK-49230, R01-AG-23686, R01-DK-063192, P30-DK-45735, U24-DK-059635, R37-HL-45095, and M01 RR-00125) and a Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award from the American Diabetes Association (to K.F.P.). This work also was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan; Takeda Science Foundation; Mochida Memorial Foundation; Suzuken Memorial Foundation; and the Naito Foundation (to K.M.).

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

K.M., K.F.P., and G.I.S. designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed and researched data, and wrote, reviewed, and edited the manuscript. S.S., C.S.C., V.T.S., A.L., A.G., H.Z., and A.K. analyzed and researched data. I.J.G., H.W., R.H.E., and H.M. contributed reagents and reviewed and edited the manuscript. G.I.S. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors are indebted to Marc Pypaert, PhD; Richard Reznick, PhD; Hui-Young Lee, PhD; Yanna Kosover; Mikhail Smolgovsky; Anthony Romanelli; Irene Moore, PhD; Shin Yonemitsu, MD; Yoshio Nagai, MD, PhD; Christina Horensavitz; Alessandro De Camilli; Aida Groszmann; Andrea Belous; Jonas Lai; Sandra Alfano; and Shuta Ishibe (all of the Yale University School of Medicine); Hajime Kondo and Ruchia Moroto (Shiga University of Medical Science); Amira Klip, PhD (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada); the staff of the Yale–New Haven Hospital Research Unit of the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation for expert technical assistance with the studies; and the volunteers for participating in this study. The authors also acknowledge the W.M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory at Yale University for expert technical assistance with the microarray experiment.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db11-1391/-/DC1.

See accompanying commentary, p. 778.

REFERENCES

- 1.Befroy DE, Petersen KF, Dufour S, et al. Impaired mitochondrial substrate oxidation in muscle of insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 2007;56:1376–1381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morino K, Petersen KF, Dufour S, et al. Reduced mitochondrial density and increased IRS-1 serine phosphorylation in muscle of insulin-resistant offspring of type 2 diabetic parents. J Clin Invest 2005;115:3587–3593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen KF, Dufour S, Befroy D, Garcia R, Shulman GI. Impaired mitochondrial activity in the insulin-resistant offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2004;350:664–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patti ME, Butte AJ, Crunkhorn S, et al. Coordinated reduction of genes of oxidative metabolism in humans with insulin resistance and diabetes: Potential role of PGC1 and NRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:8466–8471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson K-F, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet 2003;34:267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE. A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. Am J Clin Nutr 1982;36:936–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1462–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee TS, Mane S, Eid T, et al. Gene expression in temporal lobe epilepsy is consistent with increased release of glutamate by astrocytes. Mol Med 2007;13:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuel VT, Liu ZX, Qu X, et al. Mechanism of hepatic insulin resistance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem 2004;279:32345–32353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gitterman DP, Wilson J, Randall AD. Functional properties and pharmacological inhibition of ASIC channels in the human SJ-RH30 skeletal muscle cell line. J Physiol 2005;562:759–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svedberg J, Björntorp P, Smith U, Lönnroth P. Free-fatty acid inhibition of insulin binding, degradation, and action in isolated rat hepatocytes. Diabetes 1990;39:570–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu F, Jeneson JA, Beard DA. Oxidative ATP synthesis in skeletal muscle is controlled by substrate feedback. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2007;292:C115–C124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auboeuf D, Rieusset J, Fajas L, et al. Tissue distribution and quantification of the expression of mRNAs of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and liver X receptor-alpha in humans: no alteration in adipose tissue of obese and NIDDM patients. Diabetes 1997;46:1319–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krssak M, Falk Petersen K, Dresner A, et al. Intramyocellular lipid concentrations are correlated with insulin sensitivity in humans: a 1H NMR spectroscopy study. Diabetologia 1999;42:113–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rothman DL, Magnusson I, Cline G, et al. Decreased muscle glucose transport/phosphorylation is an early defect in the pathogenesis of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995;92:983–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perseghin G, Price TB, Petersen KF, et al. Increased glucose transport-phosphorylation and muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise training in insulin-resistant subjects. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1357–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perseghin G, Scifo P, De Cobelli F, et al. Intramyocellular triglyceride content is a determinant of in vivo insulin resistance in humans: a 1H-13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy assessment in offspring of type 2 diabetic parents. Diabetes 1999;48:1600–1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin ME, Marcucci MJ, Cline GW, et al. Free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance is associated with activation of protein kinase C theta and alterations in the insulin signaling cascade. Diabetes 1999;48:1270–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu C, Chen Y, Cline GW, et al. Mechanism by which fatty acids inhibit insulin activation of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1)-associated phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in muscle. J Biol Chem 2002;277:50230–50236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gavrilova O, Marcus-Samuels B, Graham D, et al. Surgical implantation of adipose tissue reverses diabetes in lipoatrophic mice. J Clin Invest 2000;105:271–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 2000;106:171–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morino K, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Molecular mechanisms of insulin resistance in humans and their potential links with mitochondrial dysfunction. Diabetes 2006;55(Suppl. 2):S9–S15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savage DB, Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Disordered lipid metabolism and the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Physiol Rev 2007;87:507–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pollare T, Vessby B, Lithell H. Lipoprotein lipase activity in skeletal muscle is related to insulin sensitivity. Arterioscler Thromb 1991;11:1192–1203 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sreekumar R, Halvatsiotis P, Schimke JC, Nair KS. Gene expression profile in skeletal muscle of type 2 diabetes and the effect of insulin treatment. Diabetes 2002;51:1913–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stump CS, Short KR, Bigelow ML, Schimke JM, Nair KS. Effect of insulin on human skeletal muscle mitochondrial ATP production, protein synthesis, and mRNA transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:7996–8001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ritov VB, Menshikova EV, He J, Ferrell RE, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE. Deficiency of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2005;54:8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Farese RV, Jr, Yost TJ, Eckel RH. Tissue-specific regulation of lipoprotein lipase activity by insulin/glucose in normal-weight humans. Metabolism 1991;40:214–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lithell H, Boberg J, Hellsing K, Lundqvist G, Vessby B. Lipoprotein-lipase activity in human skeletal muscle and adipose tissue in the fasting and the fed states. Atherosclerosis 1978;30:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun JE, Severson DL. Regulation of the synthesis, processing and translocation of lipoprotein lipase. Biochem J 1992;287:337–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doolittle MH, Ben-Zeev O, Elovson J, Martin D, Kirchgessner TG. The response of lipoprotein lipase to feeding and fasting. Evidence for posttranslational regulation. J Biol Chem 1990;265:4570–4577 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levak-Frank S, Radner H, Walsh A, et al. Muscle-specific overexpression of lipoprotein lipase causes a severe myopathy characterized by proliferation of mitochondria and peroxisomes in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest 1995;96:976–986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Roves P, Huss JM, Han DH, et al. Raising plasma fatty acid concentration induces increased biogenesis of mitochondria in skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007;104:10709–10713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ziouzenkova O, Perrey S, Asatryan L, et al. Lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins generates PPAR ligands: evidence for an antiinflammatory role for lipoprotein lipase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:2730–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang YX, Zhang CL, Yu RT, et al. Regulation of muscle fiber type and running endurance by PPARdelta. PLoS Biol 2004;2:e294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tanaka T, Yamamoto J, Iwasaki S, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta induces fatty acid beta-oxidation in skeletal muscle and attenuates metabolic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:15924–15929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stefan N, Thamer C, Staiger H, et al. Genetic variations in PPARD and PPARGC1A determine mitochondrial function and change in aerobic physical fitness and insulin sensitivity during lifestyle intervention. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:1827–1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staiger H, Staiger K, Haas C, Weisser M, Machicao F, Häring HU. Fatty acid-induced differential regulation of the genes encoding peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha and -1beta in human skeletal muscle cells that have been differentiated in vitro. Diabetologia 2005;48:2115–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neschen S, Moore I, Regittnig W, et al. Contrasting effects of fish oil and safflower oil on hepatic peroxisomal and tissue lipid content. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2002;282:E395–E401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flachs P, Horakova O, Brauner P, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine origin upregulate mitochondrial biogenesis and induce beta-oxidation in white fat. Diabetologia 2005;48:2365–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.