Abstract

Objectives

We examined factors associated with dental anxiety among a sample of HIV primary care patients and investigated the independent association of dental anxiety with oral health care.

Methods

Cross-sectional data were collected in 2010 from 444 patients attending two HIV primary care clinics in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Corah Dental Anxiety Scores and use of oral health-care services were obtained from all HIV-positive patients in the survey.

Results

The prevalence of moderate to severe dental anxiety in this sample was 37.8%, while 7.9% of the sample was characterized with severe dental anxiety. The adjusted odds of having severe dental anxiety were 3.962 times greater for females than for males (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.688, 9.130). After controlling for age, ethnicity, gender, education, access to dental care, and HIV primary clinic experience, participants with severe dental anxiety had 69.3% lower adjusted odds of using oral health-care services within the past 12 months (vs. longer than 12 months ago) compared with participants with less-than-severe dental anxiety (adjusted odds ratio = 0.307, 95% CI 0.127, 0.742).

Conclusion

A sizable number of patients living with HIV have anxiety associated with obtaining needed dental care. Routine screening for dental anxiety and counseling to reduce dental anxiety are supported by this study as a means of addressing the impact of dental anxiety on the use of oral health services among HIV-positive individuals.

Oral health care ranks among the highest unmet health-care needs for individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), as demonstrated in several national studies.1–6 Heslin et al.1 reported that in a probability sample of 2,864 HIV-positive adults, unmet dental needs were twice as prevalent as unmet medical needs. Data from Weinert et al.7 and other studies have indicated that during the era before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was available, 90% of HIV-positive individuals developed at least one oral lesion through the duration of their disease.7–9 Patton et al.10 and others11–13 have observed that with HAART, the prevalence of oral manifestations of HIV infection has generally decreased to 33%–54% of individuals over the duration of their disease. Moreover, because the occurrence of specific opportunistic oral lesions is strongly associated with lower CD4 cell counts7,14,15 and higher viral loads,14,15 the oral cavity has played an important role in monitoring the progression of HIV infection,15,16 immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome,17 and the effectiveness of HAART.18,19 Of particular concern are HIV-infected individuals with impaired immune systems because the risks associated with compromised oral health can have negative repercussions on the general health of these patients, potentially leading to serious and life-threatening consequences.7 Studies have shown that dental examiners were more successful than medical examiners in identifying oral lesions associated with HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).20,21 Together, these findings show that utilization of oral health-care services is an imperative for HIV-positive individuals.

The identification and mitigation of barriers to oral health care for HIV-infected adults is an important component of the overall management of this disease. Barriers to oral health-care access and utilization have been identified in studies of general populations. Fear, cost of treatment, lack of insurance, education, embarrassment, age, race/ethnicity, and gender are among the barriers commonly described.22–27 Dental anxiety in general populations has long been associated with delay or avoidance in seeking dental care.22–25 A construct investigated by Armfield et al. concerned “a vicious cycle of dental fear,” whereby individuals with dental anxiety avoid dental care, the avoidance contributes to deterioration of their dental condition, awareness of their worsening conditions leads to more anxiety regarding pending treatment needs, and the increased anxiety reinforces the avoidance behaviors.26

Dental anxiety has also been identified as a barrier to receiving dental health care among HIV-infected individuals, although it has not been measured with a validated scale of dental anxiety. Patton et al.28 and Shiboski et al.4 both found that the odds of not utilizing dental care were more than three times higher among HIV-positive patients who were anxious or fearful about dentists compared with those who were not fearful. The prevalence of moderate to severe dental anxiety in various samples of general populations worldwide ranges from 4.6% to 21.1%, with severe dental anxiety leading to dental avoidance.24,29–34 Much less is known regarding the prevalence of dental anxiety among HIV-positive populations.

Within this context, the specific aims of this study were to (1) identify factors associated with dental anxiety among a sample of HIV primary care patients and (2) investigate the independent association of dental anxiety with use of oral health-care services.

METHODS

Participants

The current study used cross-sectional data collected from a sample of patients who were attending two HIV primary care clinics in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Individuals were eligible for the study if they were at least 18 years of age and attending the Jackson Memorial Hospital Special Immunology (JMHSI) Clinic in Miami or the Jackson Health Systems Prevention Education and Treatment (PET) Center in Miami Beach during the study period of March–October 2010. All patients attending these two clinics are HIV-positive.

Study staff approached every third person who had entered one of the two clinics and had checked in for receipt of HIV health-care services any day the clinics were open. The clinics operated four days a week, and two trained study staff were present at each clinic during normal operating hours. Strict ethical guidelines regarding professional conduct were enforced for all project staff, all of whom were trained in appropriate conduct for obtaining informed consent and strict maintenance of participant confidentiality. If the patient was interested in participating in the study and eligible, staff accompanied the potential participant to a secure and confidential room where the research study was described. Those patients who were still interested proceeded to the informed consent process. As part of the recruitment and screening process, study personnel informed all potential participants of their right not to enroll in the study if not interested and to withdraw from the study at any time. Additionally, all study participants signed a statement attesting to their understanding that the information they provided would be kept confidential. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami and the Jackson Memorial Hospital Oversight Committee reviewed and approved the study protocol prior to the study's commencement.

Procedures

A total of 476 individuals were approached for participation in the study, with 413 recruited at the JMHSI Clinic and 63 at the PET Center. Recruitment of participants occurred at each clinic from March–October 2010. The current analysis was based upon 444 survey respondents; 32 enrollees declined to participate or presented incomplete data for the dependent variables studied, resulting in an overall participation rate of 93.3%.

After providing informed consent, the participants completed the survey instrument administered by trained study personnel. Study activities were conducted in either English or Spanish, according to the preference of the participant. The survey instrument collected demographics, dental anxiety scores, oral and general health status, utilization of oral health-care and HIV primary health-care services, alcohol- and drug-using behaviors, and questions about the participants' relationships and discussions with their HIV care providers. On completion of the survey, participants were compensated $10 for their time and effort during the 15-minute interview.

Dependent and independent variables

Two dependent variables were analyzed in this study: the first variable described dental anxiety using the Corah Dental Anxiety Scale (DAS), and the second variable was utilization of oral health-care services, measured as the time since the last dental care visit. The DAS is a scale comprising four questions relating to situational dental anxiety, where each question can be scored from 1 (lowest anxiety) to 5 (highest anxiety); the scale and questions have been published elsewhere.35 The sum of the four questions determines the DAS score, which can range from four to 20. Corah reported a high internal consistency coefficient of 0.86 and test-retest reliability of 0.82 for the DAS.35 In our study, Cronbach's alpha as a measure of internal consistency of DAS was 0.88, which is comparable to previous studies.35–37 Following Corah's35 classification of severe anxiety, we dichotomized the scores to DAS ≥15 (severe anxiety) vs. DAS, <15 (less-than-severe anxiety) for this analysis.

Utilization of oral health-care services was determined by asking the participants, “When was the last time you visited the dentist?” For the purposes of this analysis, responses were dichotomized to the last dental appointment occurring within the past 12 months vs. longer than 12 months ago. Independent variables, listed in Table 1, included individual demographic characteristics, dental care measures, HIV primary care measures, and measures of alcohol and tobacco use.

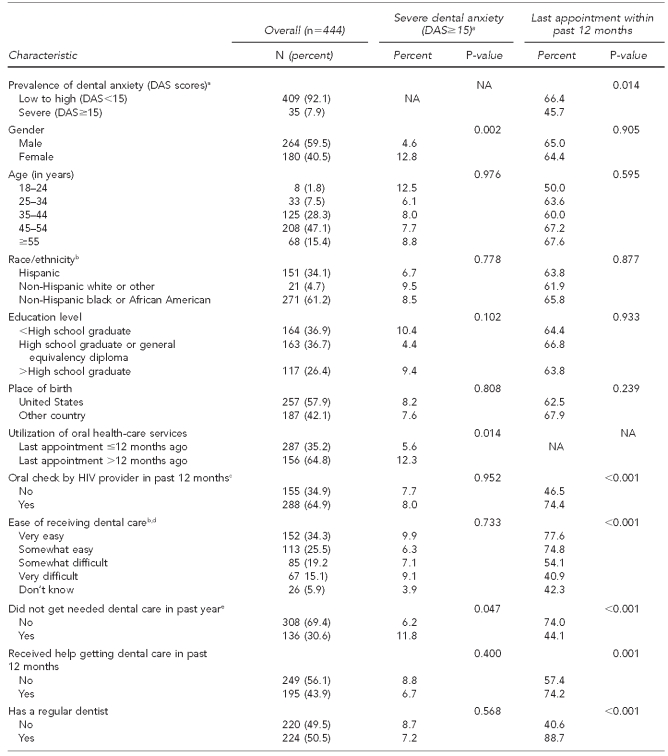

Table 1.

Individual characteristics and associations with dental anxiety and utilization of oral health care in a study of patients attending two HIV primary care clinics in Miami, Florida, March–October 2010

aSource: Corah NL. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res 1969;48:596.

bResponse missing for one individual

cSurvey instrument questions corresponding to the referenced characteristic: “In the past 12 months, did your HIV provider check your mouth, teeth, or gums?”

dSurvey instrument questions corresponding to the referenced characteristic: “How easy do you feel it is for people with HIV to get dental care?”

eSurvey instrument questions corresponding to the referenced characteristic: “In the past 12 months, have you needed dental care and did not get it?”

fSurvey instrument questions corresponding to the referenced characteristic: “How many adult teeth have you ever lost, from extraction by a dentist or falling out?”

gResponse missing for two individuals

hResponse missing for three individuals

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

DAS = Dental Anxiety Scale

NA = not applicable

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were performed to provide summary statistics of the individual, dental, and HIV primary care characteristics. Associations between each independent variable and both severe dental anxiety and utilization of oral health-care services were examined by bivariate analysis using Chi-square tests (Table 1). We began multivariable logistic regression analysis of each of the dependent variables by including independent variables with a bivariate p-value ≤0.20 in an initial model. Each of the models were further reduced in a stepwise fashion to include only those independent variables with a p-value ≤0.05, while still retaining a subset of the demographic variables independent of p-value (that is, age, ethnicity, gender, and education), following the method outlined in Hosmer and Lemeshow38 (Tables 2 and 3).

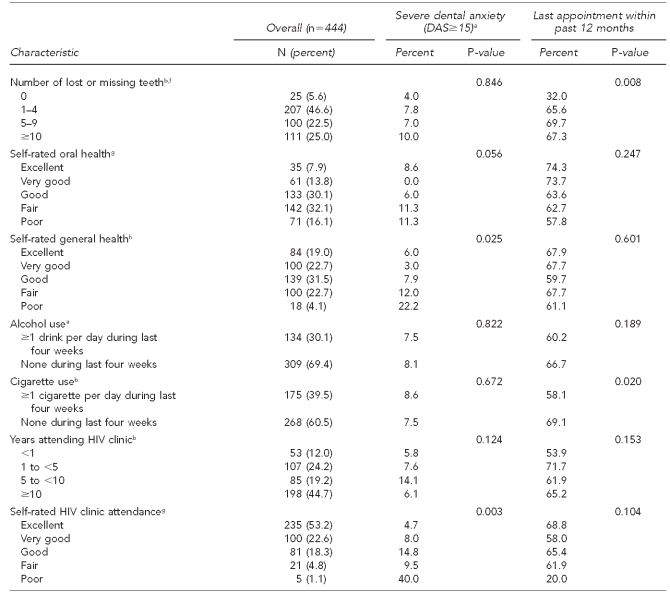

Table 2.

Logistic regression model: severe vs. less-than-severe dental anxiety among a sample of patients attending two HIV primary care clinics in Miami, Florida, March–October 2010

aAge, ethnicity, gender, and education were forced into models.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

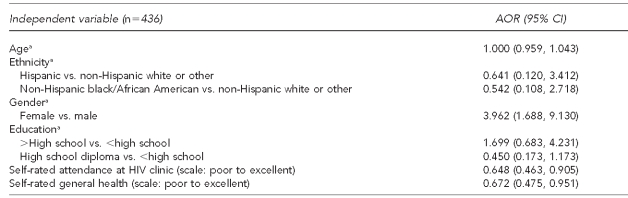

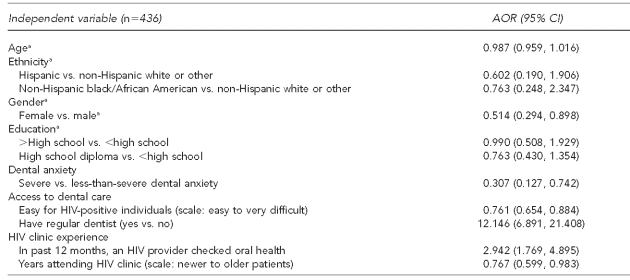

Table 3.

Logistic regression model: utilization of oral health-care services—last dental visit less than 12 months ago vs. more than 12 months ago, among a sample of patients attending two HIV primary care clinics in Miami, Florida, March–October 2010

aAge, ethnicity, gender, and education were forced into models.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

RESULTS

Demographics; DAS scores; health-care experiences for the sample; and Pearson's Chi-square tests of association among severe dental anxiety, utilization of oral health-care services, and selected independent variables are presented in Table 1. Approximately 60% of the participants were male, and about 60% identified as non-Hispanic black and 34% as Hispanic race/ethnicity; 58% were born in the U.S. Slightly more than one-third of the respondents had not completed high school or a general equivalency diploma. The median age was 47 years for males and 46 years for females. Approximately 76% of the respondents were unemployed and 10% had unstable housing (data not shown).

Oral health was perceived as fair or poor by more than 48% of participants. Half of the participants had a regular dentist, but almost two-thirds reported that it had been longer than 12 months since their last dental appointment. Slightly more than 30% reported that they had needed dental care in the past 12 months but did not get it, and almost 44% had received help from someone in attempting to get dental care. The prevalence of moderate to severe dental anxiety (DAS ≥9) was 37.8%, the prevalence of high dental anxiety (DAS=13–14) was 7.6%, and the prevalence of severe dental anxiety (DAS ≥15) was 7.9%.

Table 2 shows the multivariable logistic regression model for severe dental anxiety vs. less-than-severe dental anxiety. After controlling for age, ethnicity, gender, education, HIV health clinic attendance, and general health, the adjusted odds of having severe dental anxiety were 3.962 times greater for females than for males (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.688, 9.130). For each unit higher on the scale of self-rated attendance (from poor to excellent) at the HIV primary care clinic where patient recruitment occurred, the adjusted odds of having severe dental anxiety vs. less-than-severe dental anxiety were 64.8% lower (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.648, 95% CI 0.463, 0.905). Additionally, for each unit higher on the scale of self-rated general health (from poor to excellent), the adjusted odds of having severe dental anxiety vs. less-than-severe dental anxiety were 67.2% lower (AOR=0.672, 95% CI 0.475, 0.951).

The multivariable regression model for utilization of oral health-care services is presented in Table 3. After controlling for age, ethnicity, gender, education, access to dental care, and HIV primary clinic experience, participants with severe dental anxiety had 69.3% lower adjusted odds of utilizing oral health-care services within the past 12 months (vs. longer than 12 months ago) than participants with less-than-severe dental anxiety (AOR=0.307, 95% CI 0.127, 0.742). Respondents who reported that an HIV primary care provider had checked their mouth, teeth, or gums within the past 12 months were almost three times as likely to use oral health-care services as those who had not had an oral checkup from their HIV provider in the past year (AOR=2.942, 95% CI 1.769, 4.895). Similarly, participants who reported having a regular dentist were about 12 times as likely to have had a dental visit in the past year compared with those who did not have a regular dentist (AOR=12.146, 95% CI 6.891, 21.408). For the scale measuring perceived ease of getting dental care for HIV-positive individuals (from easy to very difficult), the adjusted odds of using oral health-care services were 23.9% lower for each unit of greater difficulty on the scale (AOR=0.761, 95% CI 0.654, 0.884). The adjusted odds of using oral health-care services were lower for females than for males (AOR=0.514, 95% CI 0.294, 0.898). Lastly, patients with a longer history of attending an HIV primary care clinic were less likely to have had a dental visit in the past 12 months (AOR=0.767, 95% CI 0.599, 0.983).

DISCUSSION

Our study represents one of the first attempts to characterize dental anxiety among HIV-positive individuals utilizing a standardized scale. Corah's DAS35 has been reported as the most widely used psychometric measure of dental fear for adults.39,40 DAS was selected for use in this study in part to provide wide comparison with previously published studies.

Our findings suggest that 7.9% of HIV-positive patients recruited from two HIV primary care clinics in Miami exhibit severe dental anxiety and 15.5% are characterized as presenting high to severe dental anxiety. These findings are higher than the prevalence of dental anxiety reported among general population (unspecified HIV status) patients in the U.S. in studies that similarly utilized the Corah DAS.35,41 Woodmansey32 reported the prevalence of severe dental anxiety as 5%; the prevalence of high to severe dental anxiety reported by Sohn and Ismail25 and Doerr et al.42 was 10%. While studies conducted outside the U.S. generally confirm this pattern of lower prevalence among the HIV-negative population,20,39 two exceptions have been found. In each of their respective studies (HIV status unknown among study participants), McGrath and Bedi43 observed a prevalence of severe dental anxiety of 11% and Thomson et al.30 measured the prevalence of high dental anxiety at 21.1%, both higher than the prevalence found in our study. No clear explanation can be offered for these observations, except perhaps in the case of Thomson et al.,30 in which the study sample was evaluated at 18 and 26 years of age; our study sample exhibited a mean age of 46.2 years (standard deviation = 9.3 years). Studies conducted across wide age groups have found that the prevalence of dental anxiety seems to peak at younger ages. For example, in two studies in Europe, prevalence of dental anxiety was greatest among Dutch females aged 26–35 years44 and among Swedes aged 20–39 years.45

Another consideration is that 37% of our study participants had less than a high school education (a proxy for low socioeconomic status), while 42% of our participants were from countries outside of the U.S. and may have had significantly different cultural perceptions regarding the importance of maintaining dental health. Shiboski et al.4 reported that both low income and nonwhite ethnicity are barriers to dental care. Lack of dental care may lead to a deteriorated state of oral health that may prompt such individuals to seek dental care only when experiencing acute pain. A history of urgent dental care encounters may predispose people to being fearful of the dentist because previous experiences with the dentist may have been painful. However, neither the associations between education nor ethnicity with severe dental anxiety or utilization of oral health-care services (i.e., fear or barrier to care) were significant in our study when controlling for other factors (Tables 2 and 3).

Higher prevalence of dental anxiety among HIV-positive patients raises concern because of the well-documented negative impact that dental anxiety has upon keeping timely and regular dental appointments4,22–25,33 and the potential for serious health consequences resulting from not maintaining oral health.7 Our findings support this concern, as dental anxiety was associated with decreased use of oral health-care services. These findings suggest that there should be increased efforts to screen people living with HIV for dental anxiety.

The HIV-positive patients in our study with the greatest odds of utilization of oral health-care services had received an oral examination by their HIV primary care provider in the past 12 months, were male, had a regular dentist, and exhibited less-than-severe dental anxiety (Table 3). These associations reinforce Armfield's concept of a “vicious cycle” involving negative reinforcement, fear, and lack of dental care.26 However, it is equally important not to overlook the potential role of HIV primary care providers, who may be the key to interventions that positively affect behaviors among these patients. Our findings suggest that patients with better HIV primary care clinic attendance have less dental anxiety. HIV primary care settings offer opportunities for providers to impress upon their patients the importance of maintaining regular appointments at the dentist and/or dental hygienist. Parallel to these efforts, HIV-positive patients should be encouraged to discuss oral health and unmet oral health needs with their primary care clinicians to address these needs in such settings as well as to provide referrals to oral health-care specialists. Clinical guidelines from the Health Resources and Services Administration's HIV/AIDS Bureau recommend that both initial and interim physical examinations of all HIV-positive patients include examinations of the oral cavity.46 Additionally, routine administration of the DAS35 as both a quick and reliable measure to identify the level of dental anxiety among patients may be helpful in the primary care setting to facilitate subsequent use of oral health-care services. For example, providers may refer anxious patients for counseling to reduce dental anxiety,47,48 perform routine examinations of the oral cavity, increase referrals to dental care providers, reinforce that dental care is easily available to people with HIV, encourage patients to establish a regular dental relationship, and help to improve patients' understanding of the importance of oral health relative to their HIV status.

Such intervention strategies could break the vicious cycle barrier to dental care services. Additionally, simple and straightforward quality-control measures—such as including an area on patients' medical charts to note completion of an oral exam by the HIV primary care provider, referral to a dentist, and a follow-up confirmation that the patient has a dentist of record—may be helpful. Providing a “grand rounds” presentation for primary care providers on this topic could be another approach to sharpen the focus within the HIV primary care settings on the importance of routine dental care for HIV-infected individuals. Such interventions appear both inexpensive and practical to employ.

Limitations

Several study limitations should be recognized. First, these data are from a sample of HIV-positive patients recruited from HIV primary care clinics in a large urban area. Therefore, generalizations to other HIV-positive individuals in rural areas or other countries should be made with caution. Second, these data are based upon self-reports, and differential recall may have been a factor regarding events of the past year; therefore, data may be affected by under- or over-reporting. Third, because the data are cross-sectional, neither the temporal relations nor causal relations are provided for the associations found.

CONCLUSION

This study is one of many49–51 that suggest the need for continued, increased focus on oral health in the HIV primary health-care setting. In this article, we outline time-efficient and cost-effective mechanisms to positively address the effects of dental anxiety on the utilization of dental health-care services. Efforts can be made to encourage HIV primary care clinicians, who already deal with the many obligations of care for the needs of their HIV-positive patients, to routinely address the oral health care of their patients. In addition, completing the circle by empowering HIV-positive patients to actively address oral health care with their primary care provider can establish a positive framework of referral to dentists and oral health-care services and break the vicious cycle of dental fear, treatment avoidance, and unmet dental health-care needs.

Footnotes

This study was supported by funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) grant #H97HA07515 and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH/NIAID)-funded Developmental Center for AIDS Research (P30AI073961). The views expressed in this article are solely the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of HHS and HRSA or NIH/NIAID, nor does mention of the department or agency names imply endorsement by the U.S. government.

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami and the Jackson Memorial Hospital Oversight Committee approved this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heslin KC, Cunningham WE, Marcus M, Coulter I, Freed J, Der-Martirosian C, et al. A comparison of unmet needs for dental and medical care among persons with HIV infection receiving care in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2001;61:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marcus M, Freed JR, Coulter ID, Der-Martirosian C, Cunningham W, Andersen R, et al. Perceived unmet need for oral treatment among a national population of HIV-positive medical patients: social and clinical correlates. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1059–63. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.7.1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coulter ID, Marcus M, Freed JR, Der-Martirosian C, Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, et al. Use of dental care by HIV-infected medical patients. J Dent Res. 2000;79:1356–61. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790060201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiboski CH, Cohen M, Weber K, Shansky A, Malvin K, Greenblatt RM. Factors associated with use of dental services among HIV-infected and high-risk uninfected women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1242–55. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonuck KA, Arno PS, Green J, Fleishman J, Bennett CL, Fahs MC, et al. Self-perceived unmet health care needs of persons enrolled in HIV care. J Community Health. 1996;21:183–98. doi: 10.1007/BF01557998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobalian A, Andersen RM, Stein JA, Hays RD, Cunningham WE, Marcus M. The impact of HIV on oral health and subsequent use of dental services. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinert M, Grimes RM, Lynch DP. Oral manifestations of HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:485–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-6-199609150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy GM. Host factors associated with HIV-related oral candidiasis. A review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:181–6. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90192-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson NW. The mouth in HIV/AIDS: markers of disease status and management challenges for the dental profession. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(Suppl 1):85–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patton LL, McKaig R, Strauss R, Rogers D, Eron JJ., Jr. Changing prevalence of oral manifestations of human immuno-deficiency virus in the era of protease inhibitor therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt-Westhausen AM, Priepke F, Bergmann FJ, Reichart PA. Decline in the rate of oral opportunistic infections following introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Oral Pathol Med. 2000;29:336–41. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2000.290708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamí-Maury IM, Willig JH, Jolly PE, Vermund S, Aban I, Hill JD, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and recurrence of oral lesions among HIV-infected patients on HAART in Alabama: a two-year longitudinal study. South Med J. 2011;104:561–6. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318224a15f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaitan Cepeda LA, Ceballos Salobreña A, López Ortega K, Arzate Mora N, Jiménez Soriano Y. Oral lesions and immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV+/AIDS patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy. Epidemiological evidence. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E85–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiboski CH, Patton LL, Webster-Cyriaque JY, Greenspan D, Traboulsi RS, Ghannoum M, et al. The Oral HIV/AIDS Research Alliance: updated case definitions of oral disease endpoints. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:481–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2009.00749.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick M, Muzyka BC, Lurie D, Salkin LM. Oral manifestations associated with HIV-related disease as markers for immune suppression and AIDS. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:344–9. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patton LL. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of oral opportunistic infections in adults with HIV/AIDS as markers of immune suppression and viral burden. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:182–8. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.108799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramírez-Amador VA, Espinosa E, González-Ramírez I, Anaya-Saavedra G, Ormsby CE, Reyes-Terán G. Identification of oral candidosis, hairy leukoplakia and recurrent oral ulcers as distinct cases of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:259–61. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramírez-Amador V, Ponce-de-León S, Anaya-Saavedra G, Crabtree Ramírez B, Sierra-Madero J. Oral lesions as clinical markers of highly active antiretroviral therapy failure: a nested case-control study in Mexico City. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:925–32. doi: 10.1086/521251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miziara ID, Weber R. Oral candidosis and oral hairy leukoplakia as predictors of HAART failure in Brazilian HIV-infected patients. Oral Dis. 2006;12:402–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruz GD, Lamster IB, Begg MD, Phelan JA, Gorman JM, el-Sadr W. The accurate diagnosis of oral lesions in human immunodeficiency virus infection. Impact on medical staging. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:68–73. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890130060010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hilton JF, Alves M, Anastos K, Canchola AJ, Cohen M, Delapenha R, et al. Accuracy of diagnoses of HIV-related oral lesions by medical clinicians. Findings from the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:362–72. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Armfield JM. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Index of Dental Anxiety and Fear (IDAF-4C+) Psychol Assess. 2010;22:279–87. doi: 10.1037/a0018678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohjola V, Lahti S, Tolvanen M, Hausen H. Dental fear and oral health habits among adults in Finland. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008;66:148–53. doi: 10.1080/00016350802089459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eitner S, Wichmann M, Paulsen A, Holst S. Dental anxiety—an epidemiological study on its clinical correlation and effects on oral health. J Oral Rehabil. 2006;33:588–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2005.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohn W, Ismail AI. Regular dental visits and dental anxiety in an adult dentate population. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:58–66. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Armfield JM, Stewart JF, Spencer AJ. The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenagy GP, Linsk NL, Bruce D, Warnecke R, Gordon A, Wagaw F, et al. Service utilization, service barriers, and gender among HIV-positive consumers in primary care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17:235–44. doi: 10.1089/108729103321655881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patton LL, Strauss RP, McKaig RG, Porter DR, Eron JJ., Jr. Perceived oral health status, unmet needs, and barriers to dental care among HIV/AIDS patients in a North Carolina cohort: impacts of race. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Locker D, Liddell A, Shapiro D. Diagnostic categories of dental anxiety: a population-based study. Behav Res Ther. 1999;37:25–37. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson WM, Locker D, Poulton R. Incidence of dental anxiety in young adults in relation to dental treatment experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:289–94. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dionne RA, Gordon SM, McCullagh LM, Phero JC. Assessing the need for anesthesia and sedation in the general population. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:167–73. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woodmansey KF. The prevalence of dental anxiety in patients of a university dental clinic. J Am Coll Health. 2005;54:59–61. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.1.59-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heaton LJ, Carlson CR, Smith TA, Baer RA, de Leeuw R. Predicting anxiety during dental treatment using patients' self-reports: less is more. J Am Dent Assoc. 2007;138:188–95. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Humphris G, King K. The prevalence of dental anxiety across previous distressing experiences. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:232–6. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Corah NL. Development of a dental anxiety scale. J Dent Res. 1969;48:596. doi: 10.1177/00220345690480041801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Locker D, Liddell A, Burman D. Dental fear and anxiety in an older adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1991;19:120–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1991.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vervoorn JM, Duinkerke AS, Luteijn F, van de Poel AC. Assessment of dental anxiety in edentulous subjects. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:177–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armfield JM. How do we measure dental fear and what are we measuring anyway? Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:107–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newton JT, Buck DJ. Anxiety and pain measures in dentistry: a guide to their quality and application. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:1149–57. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2000.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Corah NL, Gale EN, Illig SJ. Assessment of a dental anxiety scale. J Am Dent Assoc. 1978;97:816–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doerr PA, Lang WP, Nyquist LV, Ronis DL. Factors associated with dental anxiety. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1111–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGrath C, Bedi R. The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stouthard ME, Hoogstraten J. Prevalence of dental anxiety in The Netherlands. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1990;18:139–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hakeberg M, Berggren U, Carlsson SG. Prevalence of dental anxiety in an adult population in a major urban area in Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:97–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Health Resources and Services Administration (US), HIV/AIDS Bureau. Guide for HIV/AIDS clinical care, January 2011. [cited 2011 Mar 8]. Available from: URL: http://hab.hrsa.gov/deliverhivaidscare/clinicalguide11.

- 47.Crawford AN, Hawker BJ, Lennon MA. A dental support group for anxious patients. Br Dent J. 1997;183:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eli I. Behavioural interventions could reduce dental anxiety and improve dental attendance in adults. Evid Based Dent. 2005;6:46. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sroussi HY, Epstein JB. Changes in the pattern of oral lesions associated with HIV infection: implications for dentists. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:949–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tobias C, Martinez T, Bednarsh H, Fox JE. Increasing access to oral health care for PLWHA: the role of dental case managers, patient navigators, and outreach workers. [cited 2011 Jun 29]. Available from: URL: http://echo.hdwg.org/resources/report/increasing-access-oral-health-care-plwha-role-dental-case-managers-patient-navigato.

- 51.Pereyra M, Metsch LR, Gooden L. HIV-positive patients' discussion of oral health with their HIV primary care providers in Miami, Florida. AIDS Care. 2009;21:1578–84. doi: 10.1080/09540120902923030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]