Abstract

Objective

We identified factors associated with retention in oral health care for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and the impact of care retention on oral health-related outcomes.

Methods

We collected interview, laboratory value, clinic visit, and service utilization data from 1,237 HIV-positive patients entering dental care from May 2007 to August 2009, with at least an 18-month observation period. Retention in care was defined as two or more dental visits at least 12 months apart. We conducted multivariate regression using generalized estimating equations to explore factors associated with retention in care.

Results

In multivariate analysis, patients who received oral health education were 5.91 times as likely (95% confidence interval 3.73, 9.39) as those who did not receive this education to be retained in oral health care. Other factors associated with care retention included older age, taking antiretroviral medications, better physical health status, and having had a dental visit in the past two years. Patients retained in care were more likely to complete their treatment plans and attend a recall visit. Those retained in care experienced fewer oral health symptoms and less pain, and better overall health of teeth and gums.

Conclusions

Retention in oral health care was associated with positive oral health outcomes for this sample of PLWHA. The strongest predictor of retention was the receipt of oral health education, suggesting that training in oral health education is an important factor when considering competencies for new dental professionals, and that patient education is central to the development of dental homes, which are designed to engage and retain people in oral health care over the long term.

The connection between oral health and systemic health is widely acknowledged by public health professionals and is particularly important for people with chronic diseases, including people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (PLWHA).1,2 PLWHA are at increased risk for caries, periodontal disease, oral lesions, and xerostomia (dry mouth).3–6 Affected individuals may have difficulty taking medications or maintaining appropriate nutrition, further impacting their physical health.7–9

The receipt of oral health care can improve oral health, reduce the risk of oral disease, and prevent the progression of existing disease.1,10,11 Studies have found that retention in care and the receipt of regular dental examinations are associated with fewer caries,12 better periodontal health,13 and increased retention of existing teeth.14,15 Retention in care also reduces the severity of dental pain and discomfort while improving the ability to eat, speak, and socialize.16 Individuals who are retained in care receive more diagnostic and preventive services, which can arrest the progression of disease and result in lower costs per visit.17,18

However, access to and retention in dental care is problematic for many PLWHA. Lack of dental insurance or the means to pay for care are the main barriers to dental care.2,19 Patient experiences at the dental office, particularly patient-provider interactions, also impact care retention. When patients are dissatisfied or do not trust their dental providers, they are less likely to return for care.20,21 Other barriers to care reported in the literature include fear of dentists, stigma, and limited oral health literacy.9,22–26

One of the challenges of promoting retention in oral health care for PLWHA is the lack of strong evidence about the appropriate recall intervals for maintaining oral health. In HIV primary care, clinical evidence supports the receipt of clinical monitoring and laboratory tests every three to six months, depending on stage of HIV illness.27 Therefore, it is possible to test and evaluate interventions that promote retention in HIV primary care. Both federal health agencies and private foundations have sponsored demonstration projects to test strategies that promote engagement and retention in HIV primary care, but none of these projects has explicitly embraced retention in oral health care as part of its model.28,29 At the same time, it is difficult to test and evaluate retention strategies in oral health if there is inconsistent evidence about the appropriate definition or measurement of retention.30 While the standard of care in many dental practices is six months between recall appointments,12,31 systematic reviews of the research literature have found no evidence to support this visit frequency, and many argue that recall intervals should be based on the individual’s age and risk for dental disease.30,32–34

In 2006, the Health Resources and Services Administration HIV/AIDS Bureau’s Special Projects of National Significance program funded the Innovations in Oral Health Care Initiative, a five-year project to improve access to oral health care for PLWHA. This article describes the results of a study exploring the factors associated with retention in oral health care and the impact of retention on service utilization, the elimination of active disease, and oral health outcomes. The results of this analysis will contribute to a better understanding of the benefits of retention in oral health care for PLWHA and inform strategies to promote retention.

METHODS

Study sample and data collection

Fourteen dental programs across the United States enrolled 2,178 PLWHA in dental care and a longitudinal study from May 2007 to August 2009. Details about the study sites and program models are described elsewhere.35 To be eligible for the study, individuals had to be HIV-positive and 18 years of age or older. They could not have received any dental care, other than for an emergency, in the 12 months prior to study enrollment, and they had to receive at least one dental visit within 45 days of their baseline interview.

To analyze retention, we restricted the sample to individuals with an observation period of at least 18 months before the end of data collection in August 2010 (n=1,466) to maximize the opportunity to have two dental visits at least 12 months apart. We further restricted the sample to delineate two distinctly different groups of service users—those who were retained in care for more than 12 months and those who dropped out of care within six months of study enrollment, yielding a final sample of 1,237 individuals.

We collected four types of data for this longitudinal study: (1) interviews conducted at baseline, six months, and 12 months in English or Spanish; (2) laboratory values for CD4 cell counts (cells/cubic millimeter [mm3]) and viral load, collected from patient charts or laboratory slips every six months; (3) clinic data collected at each dental visit, including the visit date and whether or not a phase 1 treatment plan was completed at that visit; and (4) dental service utilization data, collected at each dental visit, including the 2006–2007 Current Dental Terminology (CDT) procedure codes for each service provided.36 All data were entered into a password-protected, Web-based database and housed at the Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH), which served as the multisite evaluation center.

Interviewers at each site were trained in both Spanish and English by the multisite evaluation center. BUSPH provided technical assistance to each site in the collection of clinic visit and service utilization data. All utilization data were audited by the lead dentist at each site and verified by chart audits conducted by the site and the oral health consultants at the multisite evaluation center at least three times during the course of the study to ensure consistency and completeness in coding and data entry across sites. All study sites and the multisite evaluation center received approval from their respective Institutional Review Boards.

Variables

The dependent variable, retention, was created using the clinic visit data. There are multiple definitions of retention or regular users in the oral health literature. Some retention studies examine visit intervals of six months,10,37 while others examine intervals of 24 months or a range of intervals.11,16,17,29 The most common visit interval used in retention studies is 12 months, or a visit at least once per year.12–14,38,39 For this study, we defined retention in care as a minimum of two visits at least 12 months apart. Non-retention was defined as less than six months of care. Thus, an individual might attend several dental appointments, but if they all occurred within the first six months, the person was considered not retained in care.

Independent variables were selected based on a review of the oral health-care access and retention literature and guided by the Institute of Medicine model on access to health services.40 The model posits that access to health-care services is influenced by structural factors, financial factors, and personal/cultural factors. These factors can be mediated by the appropriateness and efficacy of treatment. Structural factors included receipt of care in a mobile van or in a stationary clinic setting, having an HIV case manager, and the amount of time it took the patient to travel to the dentist. We did not include a dental insurance variable because dental services were provided at no cost to study participants. Personal factors included gender, age, race/ethnicity, housing, employment, education, income, and exposure to HIV through injection drug use (IDU). Health measures included years since the participant tested HIV-positive; the SF-8™ Health Survey, a standardized instrument that measures mental and physical health-related quality of life;41 laboratory values for viral load dichotomized as detectable or undetectable, and CD4 cell counts dichotomized as, <200 cells/mm3 or ≥200 cells/mm3; and whether the participant was taking antiretroviral medications. Oral health characteristics included the number of dental symptoms at initial study assessment, the length of time since the last dental visit, prior unmet need for dental care, the main reason for an unmet need, the reasons for seeking care at intake (i.e., for an examination/cleaning or to resolve a problem), and the overall health of teeth and gums.

Eleven dental symptoms—toothache, bad breath, growths/bumps, tooth decay, bleeding gums, problem with appearance, pain in jaw joints, sensitivity, sores, loose teeth, and other symptoms not listed—were summed and measured as a continuous variable. Twenty potential reasons for unmet need were collapsed into four categories: (1) financial (lack of insurance or funds to pay for care); (2) logistical (did not know where to go, could not get to the dentist); (3) stigma or fear (afraid the dentist would not be HIV friendly, fear of the dentist); and (4) other. The “other” category included 10 different reasons, including illness and addiction. The most frequent “other” response indicated that dental care was neither important nor a priority. A single mediating variable, the receipt of any oral health education during a dental visit, was included to reflect the appropriateness of treatment. Oral health education was defined as the presence of any CDT code of 1310 (nutritional counseling), 1320 (tobacco cessation counseling), or 1330 (oral hygiene instructions).

We also examined selected service-utilization characteristics of the sample and health outcomes for the retained subset of the sample as descriptors. Utilization data, including the total number of services received, the receipt of patient education services, and the receipt of a recall visit after phase 1 treatment plan completion, were obtained from CDT codes. We derived the number of clinic visits from individual dates of services, and we obtained phase 1 treatment plan completion data (the elimination of active disease and restoration of function) from clinic visit forms.

Analysis

We used measures of central tendency to describe characteristics of the study sample. Given the variation in site data, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to control for site variation in the bivariate analysis. All variables significant at the p≤0.15 level in bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. We used multivariate regression modeling techniques, using GEEs to account for within-site correlation of the data, to explore factors associated with being retained in care. Data were analyzed using SPSS®/® statistics software, version 18.0.42

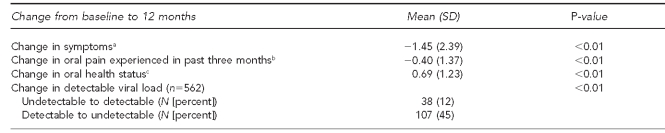

Oral health outcome measures were calculated as the change at 12 months from baseline using t-tests to compare means. These analyses were only conducted among the retained sample because the variables were obtained from patient interviews, and more than 75% of the non-retained sample did not complete a 12-month interview. The number of oral health symptoms at baseline (total possible n=11) was subtracted from the number of oral health symptoms at 12 months to obtain the change in symptom score, with a decrease in score representing a decrease in symptoms. Oral pain was measured on a five-point Likert scale, where 0 = “none at all,” and 4 = “a great deal,” with a decrease in score representing a decrease in pain. Oral health status was also measured on a five-point Likert scale, where 0 = “poor,” and 4 = “excellent,” with an increase in score representing an improvement in overall oral health status. The one health outcome measure, change in detectable viral load, was calculated using McNemar-Bowker Chi-square tests.

RESULTS

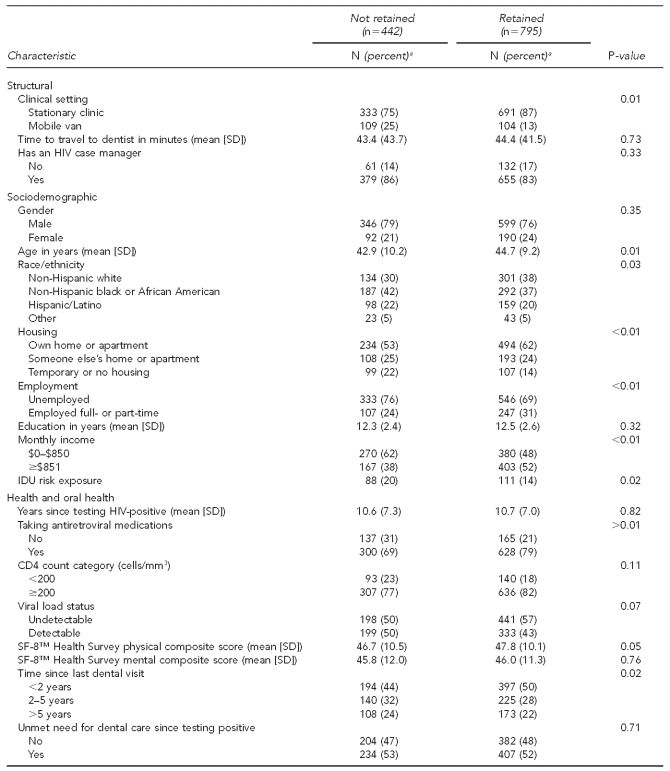

Of the 1,237 individuals included in this analysis, 442 (36%) were not retained and 795 (64%) were retained in dental care. Table 1 shows the program structural features, sociodemographic characteristics, and health and oral health characteristics of the two groups. The delivery of services at a stationary clinic, rather than in a mobile van, was the only structural factor of significance associated with retention in care. Several sociodemographic characteristics were significantly associated with retention in dental care, including older age, non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity, living in one’s own home or apartment, being employed, and having a monthly income of more than $850. IDU risk exposure was significantly associated with non-retention. Gender and education were not associated with retention in care. Health- or oral health-related characteristics significantly associated with retention in dental care included taking antiretroviral medications, having an undetectable viral load, having better self-reported physical health status, having received dental care in the previous two years, and reporting a prior unmet need for dental care due to financial reasons. There was no significant difference in retention based on overall oral health status, number of oral health symptoms, reason for seeking care, mental health status, years since testing HIV-positive, or CD4 count.

Table 1.

Characteristics of HIV-infected individuals retained and not retained in oral health care, controlling for site (n=1,237): SPNS Oral Health Initiative, 2006–2011

aTotal N may not sum to total sample due to missing data. Percentages are based on number of responses in each category, and percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

b“Not applicable” responses are from those who reported no prior unmet need for dental care.

cOut of 11 total symptoms, including toothache, bad breath, growths or bumps, tooth decay, bleeding gums, problem with appearance, pain in jaw joints, sensitivity, sores, loose teeth, and other symptoms not listed

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

SPNS = Special Projects of National Significance

SD = standard deviation

IDU = injection drug use

mm3 = cubic millimeter

SF-8™ = Short Form 8™

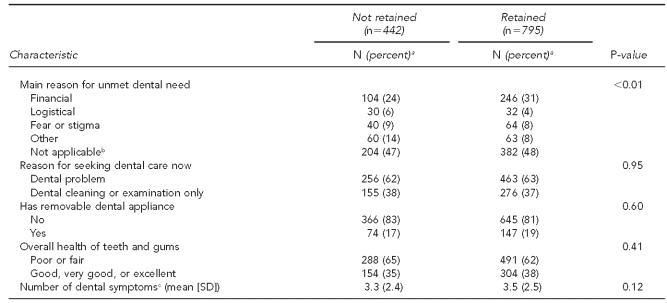

People who were retained in oral health care received significantly more visits and services than individuals who were not retained, as shown in Table 2. Although all study participants had at least one dental visit, those who were retained were significantly more likely than those not retained to have received patient education (68% vs. 27%). They were also significantly more likely to complete their phase 1 treatment plan (65% vs. 17%), and if that plan was completed, to have received a subsequent recall visit (87% vs. 64%).

Table 2.

Services received by HIV-infected individuals retained and not retained in care, controlling for site (n=1,237): SPNS Oral Health Initiative, 2006–2011

aTotal N may not sum to total sample due to missing data. Percentages are based on number of responses in each category, and percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

SPNS = Special Projects of National Significance

SD = standard deviation

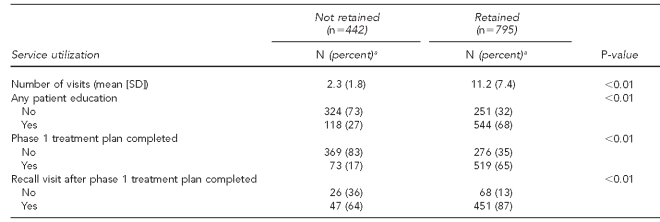

In the multivariate model, patient education was the factor most strongly associated with retention in oral health care, as shown in Table 3. Those who received patient education were 5.91 times as likely to be retained in care as those who did not receive education. Other significant factors included age (with older adults being 3% more likely to be retained in care for every additional year of age), the taking of antiretroviral medications (with those taking medications being 41% more likely to be retained than those not taking medications), and better physical health status. Individuals who had not received any oral health care in the past two years or more were 33%–36% less likely to be retained in care than those who had received care, and individuals who reported “other” reasons for prior unmet dental needs were 34% less likely to be retained than those who had no trouble obtaining dental care when needed. None of the other variables entered into the model was significant at the p≤0.05 level.

Table 3.

Factors associated with retention in oral health care among a sample of HIV-positive adults, using multiple logistic regression with generalized estimating equations to control for clustering by site (n=1,131): SPNS Oral Health Initiative, 2006–2011

aThe majority of “other” reasons included “dental care not important” or “low priority.”

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

SPNS = Special Projects of National Significance

OR = odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

Ref. = reference category

IDU = injection drug use

SF-8™ = Short Form 8™

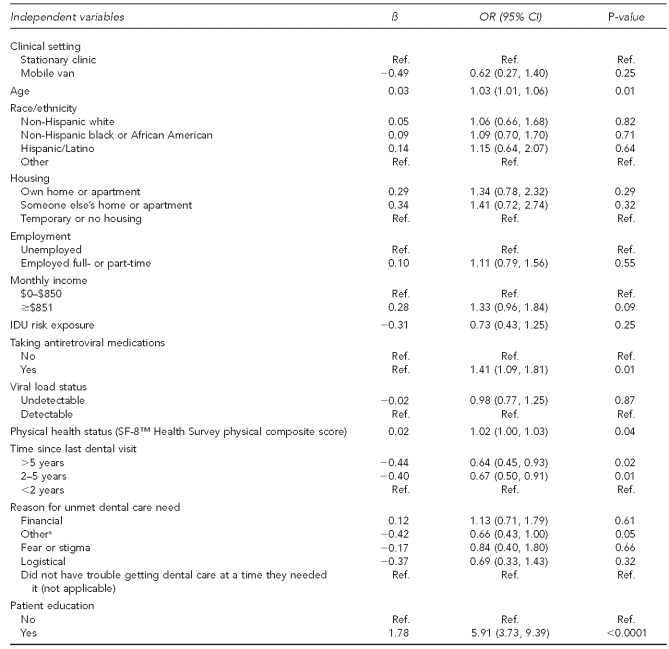

Those who were retained in care experienced improvements in their health and oral health status during a 12-month period, as shown in Table 4. They experienced a significant decline (–1.45) in overall oral health symptoms, which represented a change from 3.49 symptoms per person at baseline to 2.04 symptoms per person at 12 months. The most common symptoms included tooth decay, problems with appearance, and sensitivity, experienced by 55%–69% of the sample at baseline (data not shown). The decrease in symptoms was significant for each symptom, with the exception of problems with dentures or partials. The retained group also experienced a decline in oral pain and their overall oral health improved. The percentage of individuals whose viral load changed from detectable to undetectable also increased from baseline to 12 months among the retained sample.

Table 4.

Health changes in retained sample of HIV-positive adults from baseline to 12 months (n=605): SPNS Oral Health Initiative, 2006–2011

aOut of 11 total symptoms, including toothache, bad breath, growths/bumps, tooth decay, bleeding gums, problems with appearance, pain in jaw joints, sensitivity, sores, loose teeth, and other symptoms not listed. At baseline, the mean number of symptoms per person retained in care was 3.49.

bOn a five-point scale, where 0 = “a great deal” and 5 = “none at all”

cOn a five-point scale, where 0 = “poor” and 5 = “excellent”

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

SPNS = Special Projects of National Significance

SD = standard deviation

DISCUSSION

In this study, retention in oral health care was associated with improved overall oral health status and a reduction in pain and oral health symptoms. Those retained in care reported a significant drop in problems associated with tooth decay, sensitivity, bleeding gums, bad breath, loose teeth, sores, their appearance, and several other dental concerns after 12 months in care. Individuals who were retained in care were more likely to complete their phase I treatment plans, thereby eliminating active disease and restoring function, than those who were not retained, and they completed at least one recall visit. While these results are consistent with the results of other studies17,18 and, therefore, are not surprising, it is useful to confirm that retention in care had a positive impact on oral health and quality of life for this sample. We were surprised to find a significant change in the percentage of individuals who achieved an undetectable viral load at 12 months among the retained sample. This finding, along with the finding that taking antiretroviral medications was significantly associated with retention in multivariate analysis, may indicate that individuals who took care of their physical health were more likely to remain engaged in oral health care.

People who received oral health education, whether for nutritional counseling, tobacco cessation counseling, or oral hygiene instructions, were nearly six times as likely to be retained in care as those who did not receive any education, making this the strongest factor associated with retention in care. Patient education was far more predictive of retention than a history of IDU, race/ethnicity, housing status, employment, or monthly income, none of which was significant in multivariate analysis. In this study, individuals who reported a prior unmet need for dental care for “other” reasons were significantly less likely to be retained in care than people who reported financial, logistical, or stigma/fear barriers to care. The most common “other” responses included “I did not think it was that important” and “I did not want to go.” This finding reinforces the idea that patient education is a key component of retention. Other findings from the multivariate analysis suggest that patient education should target younger adults, individuals who are not taking antiretroviral medications, people who have been out of care for more than two years, and people with poorer health status.

The Surgeon General’s “National Call to Action to Promote Oral Health” recognized the need to expand and enhance the present makeup of the oral health workforce.43 With a number of different proposed models and providers, great emphasis has been placed on the dental procedures these new practitioners will be allowed to perform. Our data suggest that, if we want to achieve improved access to and retention in care and reduce health disparities, these new practitioners will need to demonstrate competencies in effective oral health education, counseling, and health promotion.

Nationally, health-care policy makers and providers are engaged in important efforts to improve the health of individuals with chronic illness through strategies that promote retention in care, including chronic care self-management and the establishment of medical or health homes.44–47 The health home is a model of care that replaces “episodic care based on illnesses and [an] individual’s complaints with coordinated care for all life stages…. ”48 Some leaders in public health dentistry have called for the establishment of dental homes49–51 to mirror the concept of medical homes for health care, but the dental field as a whole lags behind the medical field in establishing dental homes or dental care as part of the health home. Oral health is often excluded from mention in the establishment of health homes, despite the fact that oral disease is a chronic illness, one that is largely avoidable, and, if detected early, certainly treatable. As HIV disease is increasingly managed as a chronic illness, it is more important than ever to consider oral health as a part of the health home for PLWHA.

Limitations

Several important limitations to this study should be considered. We used a convenience sample of PLWHA who had not received dental care in the past year rather than a probability sample, and, thus, the results may not be generalizable to the national population of PLWHA. Also, some of the study participants were not in the study long enough to have two full years of data but may have only had 18 months of data; thus, there is a possibility that some of those who were considered “not retained” might have returned for more care after the study period ended. Furthermore, we were not able to compare health and oral health status outcomes for the retained group with those of the not retained group because the majority of those who were not retained in care were not retained in the study, which was the primary source of data for outcomes. Therefore, while there were significant health and oral health status changes for those who were retained in care, we cannot be certain that those changes were caused by retention in care.

In addition, we did not have access to information about other important factors that might influence care retention, such as the length of time between follow-up appointments, appointments cancelled because a mobile van broke down or a dentist resigned, or the inability of an individual to return to care due to hospitalization, incarceration, or moving out of state. Finally, although we did collect uniform data from all sites about the delivery of patient education, we did not collect specific information about the contents or duration of that education. Given the strength of the association between patient education and care retention, this is an important area for future research.

CONCLUSION

Nearly two-thirds of this sample of 1,237 PLWHA were retained in care for more than a year, and most completed their phase 1 treatment plans and experienced improvements in oral health-related quality of life. Patient education was the strongest predictor of care retention, suggesting that the training of oral health clinicians should encompass the delivery of oral health education and counseling. Retention in care is preferable to episodic emergency treatment if we want to ensure access to comprehensive, coordinated, preventive care in a dental home or health home that includes oral health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Howard Cabral, MPH, PhD, Associate Professor, Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston, Massachusetts; and Karl Hoffman, DDS, Director of Dentistry, Center for Comprehensive Care, St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital, New York, New York, for providing constructive comments and suggestions in the development of this article.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grant #H97HA07519 from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. This grant is funded through the HIV/AIDS Bureau’s Special Projects of National Significance program. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies or the U.S. government.

This research project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Boston University Medical Campus, 2006–2011.

REFERENCES

- 1.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Office of the Surgeon General. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. 2000. May, [cited 2010 Dec 17]. Available from: URL: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/oralhealth.

- 2.Marcus M, Maida CA, Coulter ID, Freed JR, Der-Martirosian C, Liu H, et al. A longitudinal analysis of unmet need for oral treatment in a national sample of medical HIV patients. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:73–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.025403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinert M, Grimes RM, Lynch DP. Oral manifestations of HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:485–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-6-199609150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryder MI. Periodontal management of HIV-infected patients. Periodontol 2000. 2000;23:85–93. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2230108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenspan JS, Greenspan D. The epidemiology of the oral lesions of HIV infection in the developed world. Oral Dis. 2002;8(Suppl 2):34–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-0825.2002.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petersen PE. Strengthening the prevention of HIV/AIDS-related oral disease: a global approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:399–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mascarenhas AK, Smith SR. Access and use of specific dental services in HIV disease. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60:172–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2000.tb03324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobalian A, Andersen RM, Stein JA, Hays RD, Cunningham WE, Marcus M. The impact of HIV on oral health and subsequent use of dental services. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shiboski CH, Cohen M, Weber K, Shansky A, Malvin K, Greenblatt RM. Factors associated with use of dental services among HIV-infected and high-risk uninfected women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:1242–55. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2005.0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheiham A. Is there a scientific basis for six-monthly dental examinations. Lancet. 1977;2:442–4. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)90620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts-Thomson K, Stewart JF. Risk indicators of caries experience among young adults. Aust Dent J. 2008;53:122–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2008.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celeste RK, Nadanovsky P. Why is there heterogeneity in the effect of dental checkups? Assessing cohort effect. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:191–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lang WP, Ronis DL, Farghaly MM. Preventive behaviors as correlates of periodontal health status. J Public Health Dent. 1995;55:10–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1995.tb02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cunha-Cruz J, Nadanovsky P, Faerstein E, Lopes CS. Routine dental visits are associated with tooth retention in Brazilian adults: the Pró-Saúde study. J Public Health Dent. 2004;64:216–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2004.tb02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kressin NR, Boehmer U, Nunn ME, Spiro A., 3rd. Increased preventive practices lead to greater tooth retention. J Dent Res. 2003;82:223–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richards W, Ameen J. The impact of attendance patterns on oral health in a general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2002;193:697–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Locker D. Does dental care improve the oral health of older adults? Community Dent Health. 2001;18:7–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hastreiter RJ, Jiang P. Do regular dental visits affect the oral health care provided to people with HIV? J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:1343–50. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heslin KC, Cunningham WE, Marcus M, Coulter I, Freed J, Der-Martirosian C, et al. A comparison of unmet needs for dental and medical care among persons with HIV infection receiving care in the United States. J Public Health Dent. 2001;61:14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ayer WA. Dental providers and oral health behavior. J Behav Med. 1981;4:273–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00844252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Graham MA, Logan HL, Tomar SL. Is trust a predictor of having a dental home? J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1550–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0081. quiz 1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patton LL, Strauss RP, McKaig RG, Porter DR, Eron JJ., Jr. Perceived oral health status, unmet needs, and barriers to dental care among HIV/AIDS patients in a North Carolina cohort: impacts of race. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:86–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng X, Heft MW, Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Effect of fear on dental utilization behaviors and oral health outcome. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohn EJ, Sankar A, Hoelscher DC, Luborsky M, Parise MH. How do social-psychological concerns impede the delivery of care to people with HIV? Issues for dental education. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1038–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seacat JD, Litt MD, Daniels AS. Dental students treating patients living with HIV/AIDS: the influence of attitudes and HIV knowledge. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:437–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg BJ, Kumar JV, Stevenson H. Dental case management: increasing access to oral health care for families and children with low incomes. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1114–21. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. 2011. Oct 14, [cited 2011 Jan 11]. Available from: URL: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 28.AIDS United. World AIDS Day marks new collaboration between the National AIDS Fund and Bristol-Myers Squibb [press release] 2009. Nov 30, [cited 2011 Jul 27]. Available from: URL: http://www.aidsfund.org/2009/12/01/world-aids-day-marks-new-collaboration-between-the-national-aids-fund-and-bristol-myers-squibb-2.

- 29.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Health Resources and Services Administration, HIV/AIDS Bureau. FY 2001 program guidance: new competitive initiative for targeted HIV outreach and intervention model development and evaluation for underserved HIV-positive populations not in care. Rockville (MD): HRSA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beirne PV, Clarkson JE, Worthington HV. Recall intervals for oral health in primary care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD004346. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004346.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davenport CF, Elley KM, Fry-Smith A, Taylor-Weetman CL, Taylor RS. The effectiveness of routine dental checks: a systematic review of the evidence base. Br Dent J. 2003;195:87–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson TJ, Nash DA. Practice patterns of board-certified pediatric dentists: frequency and method of cleaning children’s teeth. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bader J. Risk-based recall intervals recommended. Evid Based Dent. 2005;6:2–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel S, Bay RC, Glick M. A systematic review of dental recall intervals and incidence of dental caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:527–39. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox JE, Tobias CR, Bachman SS, Reznik DA, Rajabiun S, Verdecias N. Increasing access to oral health care for people living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S.: baseline evaluation results of the Innovations in Oral Health Care Initiative. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(Suppl 2):5–16. doi: 10.1177/00333549121270S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Dental Association. Current dental terminology (CDT-2007/2008) Chicago: ADA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Vogel WB. Determinants of dental care use in dentate adults: six-monthly use during a 24-month period in the Florida Dental Care Study. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:727–37. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Doty HE, Weech-Maldonado R. Racial/ethnic disparities in adult preventive dental care use. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2003;14:516–34. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crocombe LA, Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, Brennan DS, Slade GD, Poulton R. Dental visiting trajectory patterns and their antecedents. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:23–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millman M, editor. Institute of Medicine. Access to health care in America. Washington: National Academy Press; 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: a manual for users of the SF-8™ Health Survey. Lincoln (RI): Quality Metric Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.IBM SPSS, Inc. SPSS®/PASW®: Version 18.0. Chicago: IBM SPSS, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Department of Health and Human Services (US). National call to action to promote oral health. 2003. [cited 2011 Jan 14]. Available from: URL: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/topics/oralhealth/nationalcalltoaction.html.

- 44.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. 2007. Feb, [cited 2010 Dec 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.aafp.org/online/etc/medialib/aafp_org/documents/policy/fed/jointprinciplespcmh0207.Par.0001.File.dat/022107medicalhome.pdf.

- 45.Ginsburg PB, Maxfield M, O’Malley AS, Peikes D, Pham HH. Making medical homes work: moving from concept to practice. Health System Change Policy Analysis No. 1. Washington: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaén CR, Crabtree BF, Flocke SA, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:601–12. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient centered medical home resource center. [cited 2010 Dec 8]. Available from: URL: http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov.

- 48.Department of Health and Human Services (US), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Health homes for enrollees with chronic conditions. 2010. Nov 16, [cited 2010 Dec 1]. Available from: URL: http//www.cms.gov/smdl/downloads/SMD10024.pdf.

- 49.Glick M. A home away from home: the patient-centered health home. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:140–2. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS. The dental home: a primary care oral health concept. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:93–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2002.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee JY, Bouwens TJ, Savage MF, Vann WF., Jr. Examining the cost-effectiveness of early dental visits. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:102–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]