Abstract

α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate receptors (AMPARs) are of fundamental importance in the brain. They are responsible for the majority of fast excitatory synaptic transmission, and their overactivation is potently excitotoxic. Recent findings have implicated AMPARs in synapse formation and stabilization, and regulation of functional AMPARs is the principal mechanism underlying synaptic plasticity. Changes in AMPAR activity have been described in the pathology of numerous diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and epilepsy. Unsurprisingly, the developmental and activity-dependent changes in the functional synaptic expression of these receptors are under tight cellular regulation. The molecular and cellular mechanisms that control the postsynaptic insertion, arrangement, and lifetime of surface-expressed AMPARs are the subject of intense and widespread investigation. For example, there has been an explosion of information about proteins that interact with AMPAR subunits, and these interactors are beginning to provide real insight into the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the cell biology of AMPARs. As a result, there has been considerable progress in this field, and the aim of this review is to provide an account of the current state of knowledge.

I. Introduction

A. Classes of Glutamate Receptors

The amino acid glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system (CNS1), and it exerts its physiological effects by binding to a number of different types of glutamate receptors (GluRs). Glutamate receptors can be divided into two functionally distinct categories: those that mediate their effects via coupling to G-protein second messenger systems, the metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and ionotropic ligand-gated ion channels (Simeone et al., 2004). Based largely upon the work of Watkins and coworkers (Watkins, 1981, 1991; Watkins et al., 1981), the ionotropic glutamate receptors have been separated into three distinct sub-groups based upon their pharmacology (for related reviews, see Dingledine et al., 1999; Barnes and Slevin, 2003; Mayer and Armstrong, 2004). These are the α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, and kainate (KA) receptors. However, it is important to note that AMPARs are responsive to kainate.

The pharmacologically isolated families of receptors were subsequently found to be encoded by distinct gene families. AMPARs comprise four subunits named GluR1 to GluR4 (also called GluRA–GluRD). The GluR1 subunit was first cloned after screening an expression library (Hollmann et al., 1989), and subsequent cDNA homology screens revealed the remaining GluR2, GluR3, and GluR4 homologs (Boulter et al., 1990; Keinanen et al., 1990; Nakanishi et al., 1990; Sakimura et al., 1990).

B. AMPA Receptor Topology

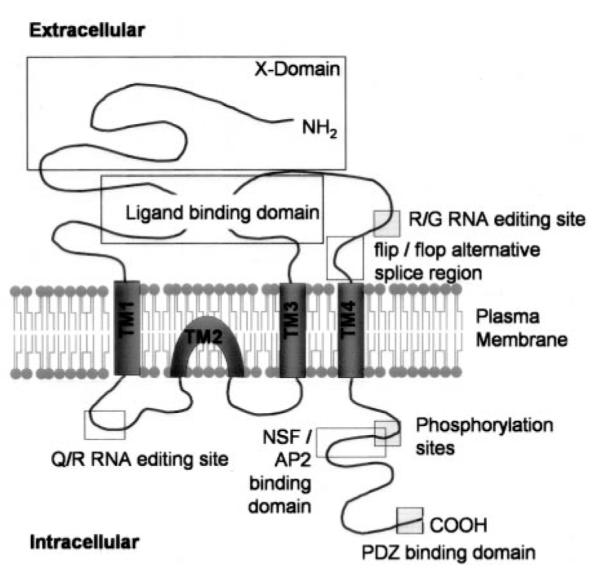

The schematic topology of an AMPAR subunit is illustrated in Fig. 1. This structure has been based largely on biochemical investigations as well as homology between the AMPARs and prokaryotic amino acid receptors (reviewed in Paas, 1998). The molecular architecture of each AMPAR subunit (GluR1–4) is very similar; each comprises ~900 amino acids and has a molecular weight of ~105 kDa (Rogers et al., 1991). There is approximately 70% sequence homology between genes encoding each subunit, although genes may undergo alternative splicing in two distinct regions, resulting in subunits that have either long or short C termini, and flip or flop variants in an extracellular domain (for review, see Black and Grabowski, 2003).

FIG. 1.

Schematic showing the topology of an AMPA receptor subunit. Each subunit consists of an extracellular N-terminal domain, four hydrophobic regions (TM1–4), and an intracellular C-terminal domain. The ligand-binding site is a conserved amino acid pocket formed from a conformational association between the N terminus and the loop linking TM3 and TM4. A flip/flop alternative splice region and R/G RNA editing site are also present within the TM3/TM4 loop. TM2 forms an intracellular re-entrant hairpin loop which contributes to the cation pore channel and is also the site for Q/R RNA editing in the GluR2 subunit. The intracellular C terminus contains phosphorylation sites and conserved sequences that have been shown to interact with a number of intracellular proteins, for example, PDZ domain-containing proteins and the ATPase NSF.

1. The N Terminus

Each subunit includes an extracellular N terminus, four hydrophobic domains (TM1–4), and an intracellular C terminus (Fig. 1). In eukaryotes, the N terminus contains the N-terminal domain of ~400 amino acids and a ~150 amino acid ligand-binding core. The N-terminal domain is also known as the X-domain because of its unknown function (Kuusinen et al., 1999). Suggestions for X-domain function include receptor assembly, allosteric modulation of the ion channel, and binding of a second ligand. The X-domains of GluR4 form dimers in solution (Kuusinen et al., 1999) and confer specificity for AMPARs, as opposed to KARs upon coassembly with other subunits (Leuschner and Hoch, 1999). However, deletion of the entire X-domain of GluR4 did not alter the function of homomers expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 cells, indicating that it is not involved in homomeric assembly of this subunit (Pasternack et al., 2002). The structure of this part of AMPARs is suggestive of a ligand-binding site, but no endogenous ligands have been found to bind here, although Zn2+ modulates at a similar site on NMDARs (Mayer and Armstrong, 2004). Intriguingly, the N terminus of GluR2 is involved in dendritic spine morphogenesis, perhaps through a receptor-ligand complex (Passafaro et al., 2003).

The ligand-binding core of AMPARs confers pharmacological specificity to the receptors; indeed, swapping the domains of AMPA and KARs swapped both their affinity for the ligand and desensitization properties and proved that this is the glutamate binding site (Stern-Bach et al., 1994, 1998). The structures of the ligand binding cores of GluR2 and GluR4 have been studied intensively (Jayaraman et al., 2000; Kubo and Ito, 2004; McFeeters and Oswald, 2004), and this is the only part of any AMPAR to be crystallized so far (Armstrong et al., 1998). For GluR2, the ligand-binding core has been crystallized with various pharmacological agents (Johansen et al., 2003). This approach gives an insight into the mode of action of some AMPAR agonists and antagonists and promises to be a valuable tool for the rational design of future drugs (reviewed in Stensbol et al., 2002; Mayer and Armstrong, 2004).

2. Hydrophobic Regions

The transmembrane orientation of the AMPAR subunits was initially elucidated by the use of specific antibodies, N-glycosylation pattern, and proteolytic sites (Molnar et al., 1994; Wo et al., 1995). Together, these studies demonstrated that the mature N terminus is expressed on the exterior surface of the neuron (Hollmann et al., 1994; Bennett and Dingledine, 1995; Seal et al., 1995), and subsequent work showed that the TM1, TM3, and TM4 regions are all transmembrane spanning domains, whereas TM2 forms a hairpin loop on the intracellular side of the cell membrane (see also Wo and Oswald, 1994) (Fig. 1). Similar to K+ channels, the re-entrant loop contributes to the cation pore channel (Kuner et al., 2003), although the specificity of AMPARs differ in that they gate Na+ and Ca2+ in preference to K+, perhaps because of a comparatively larger pore size (Tikhonov et al., 2002).

3. The Intracellular C Terminus

The intracellular C terminus of eukaryotic AMPARs has been shown to be the interaction site for a range of different proteins, many of which are involved in the receptor trafficking (reviewed in Henley, 2003) and synaptic plasticity (reviewed in Malenka, 2003; Sheng and Hyoung Lee, 2003). The functions of AMPAR interactors are under intense scrutiny and will be discussed in greater detail below.

C. Pharmacology

AMPARs gate Na+ and Ca2+ in response to ligand binding, with conductance and kinetic properties of the receptor depending on the subunit composition (Mat Jais et al., 1984; Hollmann et al., 1991; Jonas, 1993). This influx of ions causes a fast excitatory postsynaptic response, and the Ca2+ component can also activate second messenger pathways (Michaelis, 1998), including many protein kinases (Wang et al., 2004); indeed, AMPARs have been reported to have metabotropic as well as ionotropic properties (Wang and Durkin, 1995; Wang et al., 1997). For researchers investigating the function of AMPARs in in vitro preparations, it may also be interesting to note that AMPARs may be potentiated by serum factors (Nishizaki et al., 1997).

There are many drugs available that act on AMPARs, and listing them is beyond the scope of this review (but see Stensbol et al., 2002; Stone and Addae, 2002; Weiser, 2002; McFeeters and Oswald, 2004; O’Neill et al., 2004; Stromgaard and Mellor, 2004).

D. Post-Transcriptional Modification

1. Splice Variants

All four AMPAR subunits undergo alternative splicing in an extracellular region N-terminal to the fourth transmembrane domain to give “flip” and “flop” splice variants (Sommer et al., 1990) (see Fig. 1). This modifies the channel’s kinetic and pharmacological properties with flip splice variants desensitizing four times slower than flop (Mosbacher et al., 1994; Koike et al., 2000) and confers different sensitivity to allosteric modulators cyclothiazide (Partin et al., 1994; Kessler et al., 2000), 4-[2-(phenylsulfonylamin-o)ethylthio]-2,6-difluoro-phenoxyacetamide (Sekiguchi et al., 1997, 1998), zinc (Shen and Yang, 1999), and lithium (Karkanias and Papke, 1999), although affinity to AMPA is unchanged (Arvola and Keinanen, 1996). Expression levels of the different splice variants is region and cell-type specific (Sommer et al., 1990; Fleck et al., 1996; Lambolez et al., 1996) and developmentally regulated, for example, in the cerebellum (Mosbacher et al., 1994), as well as modified by physiological insults (Zhou et al., 2001b), lesions (Pires et al., 2000), and disease (Seifert et al., 2002, 2004; Tomiyama et al., 2002). This means that the number of permutations of AMPARs is very large giving a potential to fine-tune the kinetic properties of the channel.

Further to the flip and flop splice variants, GluR1, −2, and −4 can also undergo alternative splicing in the C terminus to give “long” isoforms (Gallo et al., 1992; Kohler et al., 1994); however the “short” isoform of GluR1 has not been reported. The short isoform of GluR2 is the most abundant, accounting for over 90% of total GluR2 (Kohler et al., 1994), and the long form of GluR4 is predominant (Gallo et al., 1992). GluR3 has a short C terminus due to a lack of splice sites in the C terminus. The alternative splice variants are able to bind different interacting proteins because the PDZ binding motif is only present in the short form (Dev et al., 1999). In consequence, much of the work in the field of AMPAR interactors has focused on the short form of GluR2.

2. RNA Editing

The genomic DNA of the GluR2 subunit of AMPARs contains a glutamine (Q) residue at amino acid 607. However, the vast majority of neuronal cDNA contains an arginine (R) at this position and occurs via a process of nuclear RNA editing (Sommer et al., 1991; Cha et al., 1994; Seeburg et al., 1998; Seeburg and Hartner, 2003). The edited residue is found in the channel-forming segment of the receptor, and the amount and presence of the edited subunit alters the kinetics and divalent ion permeability of the resulting receptors (Burnashev et al., 1992, 1995; Geiger et al., 1995), although it is not linked to receptor desensitization (Thalhammer et al., 1999). GluR2(R)-containing AMPARs have a low permeability to Ca2+ and low single-channel conductance because of the size and charge of the amino acid side chain in the edited form (Burnashev et al., 1992, 1996; Swanson et al., 1997). Nonetheless, GluR2(R)-containing AMPARs can still participate in intracellular Ca2+ signaling (Utz and Verdoorn, 1997) and can be trafficked in a Ca2+-dependent way (Liu and Cull-Candy, 2000). Furthermore, editing at this position has been shown to regulate endoplasmic reticulum retention (Greger et al., 2002) and tetramerization of AMPARs (Greger et al., 2003). Edited and unedited forms of the receptor have different sensitivity to the pharmacological agents Joro Spider toxin and adamantine derivatives (Meucci et al., 1996; Magazanik et al., 1997; McBain, 1998), and editing at this position is developmentally, region- and cell-specifically regulated (Lerma et al., 1994; Nutt and Kamboj, 1994). Indeed, changes in the levels of editing occur during differentiation of neurons and glia (Meucci et al., 1996; Lai et al., 1997).

Because of the link between calcium influx and excitotoxicity, changes in the amount of edited GluR2 have been implicated in a number of diseases including schizophrenia, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease (Akbarian et al., 1995), epilepsy (Brusa et al., 1995), and malignant glioma (Maas et al., 2001) with most research being focused on amyotropic lateral sclerosis (Takuma et al., 1999; Kawahara et al., 2003b, 2004), although the process is not involved in ischemia (Kamphuis et al., 1995; Paschen et al., 1996; Rump et al., 1996; but see Tanaka et al., 2000). Editing at this position is not essential for brain development (Kask et al., 1998), but mice have neurological deficits when editing does not take place (Feldmeyer et al., 1999).

Further, to the Q/R site of GluR2, GluR2, −3, and −4 may be edited at another site, the R/G site, in a region that immediately precedes the flip/flop splice module in the N terminus of the molecule (Lomeli et al., 1994; Fig. 1). This modification changes the desensitization and resensitization of the resulting AMPAR (Lomeli et al., 1994; Krampfl et al., 2002) and may be involved in epilepsy (Vollmar et al., 2004) and, in contrast to the Q/R site, ischemia (Yamaguchi et al., 1999).

The RNA-dependent adenosine deaminase 2 carries out RNA editing of AMPARs (Higuchi et al., 2000; Ohman et al., 2000), and like the edited and unedited forms of AMPAR subunits, expression levels of the enzyme are developmentally and regionally regulated. Indeed, it has been shown that RNA-dependent adenosine deaminase 2 abundance regulates levels of edited GluR2 (Kawahara et al., 2003a).

E. Post-Translational Modification

1. Glycosylation

All AMPARs have sites for asparagine (N)-linked glycosylation (Hullebroeck and Hampson, 1992; Breese and Leonard, 1993; Keinanen et al., 1994) in the extracellular domains of the protein, with two conserved sites in the S1 domain that forms part of the ligand-binding domain (Arvola and Keinanen, 1996; reviewed in Standley and Baudry, 2000; Pasternack et al., 2003). The functional consequence of the addition of these oligosaccharides is not clear. Inhibition of glycosylation with tunicamycin was found to prevent functional expression of recombinant AMPARs (Musshoff et al., 1992; Kawamoto et al., 1994), but later the drug itself was reported to inhibit AMPARs regardless of glycosylation state (Maruo et al., 2003). Studies of recombinantly expressed S1-S2 domain fusion proteins show that this form of post-translational modification does not affect the ligand-binding site (Arvola and Keinanen, 1996; Pasternack et al., 2003), however, the desensitizing lectin concanavalin A potentiates AMPAR currents by binding to these carbohydrates, with GluR2 remaining unaffected (Everts et al., 1997). This suggests that glycosylation of different AMPAR subunits may have different functional effects. It appears that only surface and synaptically expressed AMPARs possess the mature glycosylated form (Hall et al., 1997; Standley et al., 1998), and the exact nature of the oligosaccharides involved has been identified (Clark et al., 1998). It is likely that this protein modification is involved in the maturation and transport of the receptor or could protect AMPARs from proteolytic degradation. Indeed, the aberrant glycosylation of GluR3 can lead to proteolysis and release of an autoimmunogen leading to Rasmussen’s encephalitis (Gahring et al., 2001).

2. Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation of ligand-gated ion channels can regulate the properties of the channel, its intermolecular interactions, and trafficking of the protein (reviewed in Swope et al., 1999). The regulation of AMPAR phosphorylation adds a further complex level of receptor modulation beyond subunit composition, splice variants, and other post-translational modifications (Carvalho et al., 2000; Gomes et al., 2003). Phosphorylation of receptor subunits can occur basally or in response to particular types of synaptic activity, and each AMPAR subunit has its own calcium and kinase profile (Wyneken et al., 1997). In particular, the role of GluR1 phosphorylation in synaptic plasticity has been studied in detail (reviewed in Roche et al., 1994; see Yakel et al., 1995). However, some phosphorylation sites are thought to be shared by all AMPARs: a residue between 620 and 638 of GluR1 and the equivalent sites in all other AMPARs is phosphorylated in vitro by CaMKII leading to enhanced responses in synaptic plasticity (Yakel et al., 1995), and although most research has centered on the role of CaMKII, it is possible that CaMKIV may play a similar role (Kasahara et al., 2000). There also appears to be a general role for developmental regulation of AMPAR properties by phosphorylation (Shaw and Lanius, 1992; Li et al., 2003). Furthermore, a GluR2 Ser 696 phosphospecific antibody helped demonstrate phosphorylation of this and analogous sites in all other AMPARs in response to agonist by PKC (Nakazawa et al., 1995a,b). This phosphorylation is thought to underlie long-term desensitization.

In addition to modulation of AMPAR phosphorylation in response to glutamatergic synaptic activity, PKA phosphorylation of AMPARs, primarily GluR1, is enhanced by D1 dopamine receptor activation (Price et al., 1999; Snyder et al., 2000; Chao et al., 2002) and may play a role in Parkinson’s disease (Chase et al., 2000; Oh et al., 2003). Indeed, dopamine receptors may influence synaptic plasticity of AMPARs (Wolf et al., 2003) by increasing PKA-mediated AMPAR insertion (Mangiavacchi and Wolf, 2004). Serotonin hydroxytryptamine 1A receptors can, on the other hand, inhibit CaMKII phosphorylation of AMPARs (Cai et al., 2002b).

a. GluR1

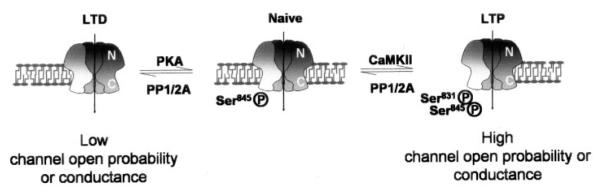

GluR1 is phosphorylated at multiple sites on the C terminus. PKC and CaMKII phosphorylate Ser 831 (Roche et al., 1996; Mammen et al., 1997), whereas PKA phosphorylates Ser 845 (Mammen et al., 1997). Differential phosphorylation of both sites occurs according to activity (Blackstone et al., 1994) leading to changes in synaptic efficacy (Fig. 2) and phosphorylation by PKA and PKC may play a role in nociception (Fang et al., 2003a,b; Nagy et al., 2004). Furthermore, phosphorylation at both PKA and CaMKII sites controls synaptic incorporation of these receptors (Esteban et al., 2003) and may be enhanced by the constitutive activity of phospholipase A2 (Menard et al., 2005).

FIG. 2.

Schematic illustrating that phosphorylation of the GluR1 AMPA receptor subunit may act as a bidirectional switch in synaptic plasticity.

AMPARs present in the postsynaptic density are phosphorylated by CamKII, and there is evidence that the PKA site is occluded in this location (Figurov et al., 1993; Vinade and Dosemeci, 2000). CaMKII phosphorylation plays a role in synaptic unsilencing (Liao et al., 2001) and enhancement (Figurov et al., 1993; Nishizaki and Matsumura, 2002), ischemia (Takagi et al., 2003; Fu et al., 2004), inflammation (Guan et al., 2004), and LTP (Hayashi et al., 1997; of depressed synapses: Strack et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2000) perhaps by increasing the AMPAR-mediated current (Derkach, 2003; Vinade and Dosemeci, 2000) and/or by modulating an interaction between GluR1 and a PDZ-containing protein (Hayashi et al., 2000). Interestingly, amyloid β protein prevents the activation of CaMKII and AMPAR phosphorylation during LTP (Zhao et al., 2004). Dephosphorylation of this site by protein phosphatase 1 leads to depotentiation (Lee et al., 2000; Vinade and Dosemeci, 2000; Huang et al., 2001).

PKA phosphorylation leads to potentiation of homomeric peak current (Roche et al., 1996; Vinade and Dosemeci, 2000) by increasing the peak open probability (Banke et al., 2000) and leads to LTP in naive synapses (Lee et al., 2000). Dephosphorylation occurs via a calcineurin-mediated pathway (Snyder et al., 2003) and is a feature of NMDA-dependent LTD expression at naive synapses (Kameyama et al., 1998; Ehlers, 2000; Lee et al., 2000; Launey et al., 2004). The interacting proteins SAP-97 and A-kinase-anchoring protein 79 are thought to direct basal PKA phosphorylation of GluR1 and calcium-dependent dephosphorylation at this site (Colledge et al., 2000; Lisman and Zhabotinsky, 2001; Tavalin et al., 2002).

It is clear that the effects of GluR1 (de)phosphorylation at the major CaMKII and PKA sites on synaptic plasticity depends on the history of the synapse (Lee et al., 2000), and it is becoming increasingly evident that these kinases and phosphatases play important roles in development, synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory (Vianna et al., 2000; Genoux et al., 2002; D’Alcantara et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2003a; Lu et al., 2003), although a role for GluR1 dephosphorylation in LTD maintenance rather than induction has been postulated (Brown et al., 2005). See Fig. 2 for a model of how the phosphorylation state of GluR1 relates to the plastic state of the synapse. GluR1 phosphorylation by the Src family tyrosine kinase Fyn also occurs in vitro and protects the receptors from calpain digestion which could modulate trafficking events or channel properties (Rong et al., 2001).

b. GluR2

GluR2 is phosphorylated by PKC at Ser 880 in the PDZ binding site. This differentially regulates binding of AMPAR binding protein (ABP)/glutamate receptor-interacting protein 1 (GRIP1) and protein interacting with C kinase (PICK)1, with a decrease in ABP/GRIP binding but not PICK1 in response to phosphorylation (Matsuda et al., 1999; Seidenman et al., 2003). Furthermore, ABP binding to GluR2 prevents this phosphorylation (Fu et al., 2003). Phosphorylated GluR2 has been shown to recruit PICK1 to synapses apparently causing the release of the GluR2-PICK1 complex from synapses facilitating internalization (Chung et al., 2000; Seidenman et al., 2003) and LTD (Matsuda et al., 2000; Xia et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2001; Chung et al., 2003). Interestingly, cerebellar LTD has also been shown to involve a mitogen-activated protein kinase step that converts transiently phosphorylated AMPARs to stably phosphorylated ones (Kuroda et al., 2001), and LTD-inducing protocols lead to tyrosine phosphorylation of GluR2 and, consequently, endocytosis of the receptors (Ahmadian et al., 2004). Indeed, phosphorylation of Tyr 876 near the C terminus of the receptor by a src family tyrosine kinase has a similar effect on GRIP1 and PICK1 binding to PKC phosphorylation of Ser 880, although this phosphorylation is involved in AMPA- and NMDA-induced internalization of these receptors (Hayashi and Huganir, 2004). Furthermore, potential PKC phosphorylation sites have also been identified in the C terminus of GluR2, including Ser 863 (Hirai et al., 2000; McDonald et al., 2001).

c. GluR3

There has been no systematic study into the regulation of GluR3 subunit phosphorylation.

d. GluR4

Recombinant homomeric GluR4 is the most rapidly desensitizating of the AMPARs, a property that may be regulated by (de)phosphorylation. This subunit is phosphorylated by PKC in response to activation of the kinase/receptor (Carvalho et al., 2002). PKC directly interacts with the membrane-proximal C terminus of the receptor, phosphorylating at Ser 482, and leading to increased surface expression of recombinant receptors (Correia et al., 2003; Esteban et al., 2003), and Thr 830 is also a potential PKC site (Carvalho et al., 1999). Ser 842 can be phosphorylated by PKA which modulates surface expression of the receptor (Gomes et al., 2004).

F. Expression Patterns

1. Regional Distribution in the Brain

In situ hybridization studies (Keinanen et al., 1990; Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1991), receptor autoradiography using [3H]AMPA and [3H]glutamate (Monaghan et al., 1984), and immunocytochemistry using antibodies directed against individual AMPAR subunits (Petralia and Wenthold, 1992; Martin et al., 1993) demonstrated the widespread and varied distribution of AMPARs in the brain (reviewed in Hollmann and Heinemann, 1994). The hippocampus, outer layers of the cortex, olfactory regions, lateral septum, basal ganglia. and amygdala of the CNS are enriched in GluR1, GluR2, and GluR3 (Keinanen et al., 1990; Beneyto and Meador-Woodruff, 2004). In contrast, GluR4 mRNA and immunolabeling is low to moderate throughout the rat CNS, except in the reticular thalamic nuclei and the cerebellum where levels are high (Petralia and Wenthold, 1992; Martin et al., 1993; Spreafico et al., 1994).

2. Neuronal and Glial Expression

Interestingly, AMPARs have also been found on glial cells (Gallo and Russell, 1995; Garcia-Barcina and Matute, 1998; Janssens and Lesage, 2001), where they appear to be involved in excitotoxicity (Yoshioka et al., 1996; Park et al., 2003) and ischemia pathology (Gottlieb and Matute, 1997; Meng et al., 1997). Activation of these receptors on some glia can lead to the release of ATP or nitric oxide, which may act as autocrine or paracrine messengers (Queiroz et al., 1999; Comoletti et al., 2001) and can affect glial morphology (Ishiuchi et al., 2001). It has recently been demonstrated that mouse hippocampal astrocytes may be categorized into AMPAR-expressing cells or glutamate transporter cells, which adds yet another layer of complexity (Wallraff et al., 2004). Glia-glia coupling (Muller et al., 1996) and neuron-glia signaling is an emerging area of interest in this field, with work centering on the Bergmann glia of the cerebellum (Mennerick et al., 1996; Clark and Barbour, 1997; Iino et al., 2001; Dziedzic et al., 2003; Millan et al., 2004). Indeed, it appears to be possible to induce a form of LTP in cerebellar glia by stimulating neighboring neurons (Linden, 1997), and a form of epilepsy appears to be coupled to a change in AMPAR splice variant expression in hippocampal glia (Seifert et al., 2002). It has been proposed that neuron-glia signaling in the hypothalamus may also control sexual development (Dziedzic et al., 2003).

3. Developmental Regulation

AMPAR mRNA can be detected at very early stages of development. In embryonic rat brain, GluR2 mRNA is near ubiquitous, with GluR1, GluR3, and GluR4 more differentially expressed (Monyer et al., 1991). GluR1 protein was found in rat brain as early as E15.5 and GluR4 at E11 in mouse brain (Durand and Zukin, 1993; Martin et al., 1998). Later in development, studies on postnatal tissue have suggested that expression levels of GluR1–4 increase gradually, concurrent with synapse development, and appear to peak in the third postnatal week (Insel et al., 1990; Pellegrini-Giampietro et al., 1991; Durand and Zukin, 1993; Standley et al., 1995; Arai et al., 1997; Martin et al., 1998). However, immunoreactivity to GluR4 in rat brain was not apparent until P14, after which its levels of immunoreactivity increased gradually until adulthood (Hall and Bahr, 1994). Developmental changes in the expression levels of AMPARs in hippocampal organotypic slice cultures (Fabian-Fine et al., 2000) and living cultured hippocampal neurons have also been reported (Pickard et al., 2000; Molnar et al., 2002), concluding that maturation of synapses may be retarded in vitro. AMPAR expression is also developmentally regulated in the spinal cord (Jakowec et al., 1995; Kalb and Fox, 1997), the visual system (Silveira dos Santos Bredariol and Hamassaki-Britto, 2001; Batista et al., 2002; Hack et al., 2002), and the auditory system (Sugden et al., 2002). During neonatal development, AMPAR incorporation into the plasma membrane occurs prior to synaptogenesis when GluR1-containing AMPARs cluster at potential postsynaptic sites (Martin et al., 1998). As well as developmental regulation of receptor subunit expression, splicing of AMPARs changes during development (Monyer et al., 1991; Tonnes et al., 1999), as can the kinetics of channel opening (Koike-Tani et al., 2005; Wall et al., 2002). The Ca2+-permeability of some glia also appears to be developmentally regulated (Backus and Berger, 1995).

4. Subcellular Expression Patterns

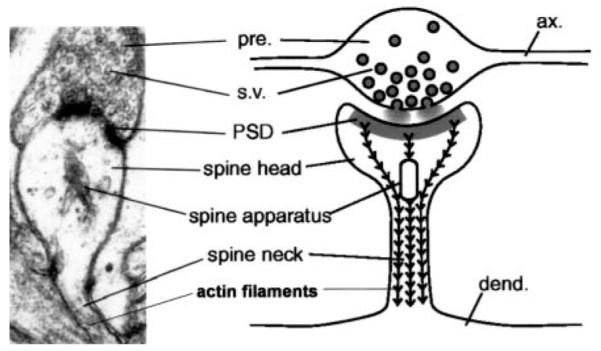

Subcellular fractionation experiments have indicated an enrichment of AMPARs in both synaptic membrane and postsynaptic density preparations (Rogers et al., 1991; Blackstone et al., 1992; Archibald and Henley, 1997). For a diagram of the morphology of an excitatory synapse at the electron-micrograph level, please see Fig. 3. Microscopy confirmed these findings in many brain areas (Petralia and Wenthold, 1992; Craig et al., 1993; Baude et al., 1994; Spreafico et al., 1994; Petralia et al., 1997). However, some AMPARs have also been detected extrasynaptically and within the cytoplasm of individual neurons (Baude et al., 1994, 1995). Consistent with this observation, a large number of intracellular AMPARs have been identified by biochemical studies (Barnes and Henley, 1993; Hall and Soderling, 1997; Hall et al., 1997; Lee et al., 2001). Overall, these studies suggest 60 to 70% of the total AMPAR population is intracellular. As discussed in more detail below, it has been speculated that this intracellular pool of AMPARs may play a role in synaptic plasticity and development via the “silent synapse” hypothesis.

FIG. 3.

Electron micrograph and corresponding diagram depicting a single excitatory synapse. The electron dense PSD directly opposes the neurotransmitter release sites located on the presynaptic bouton and the spine neck and spine apparatus are clearly defined (reproduced with permission from Fischer et al., 2000).

G. Plasma Membrane Distribution of AMPA Receptors

1. Postsynaptic Membrane

It is well established that AMPARs reside in the postsynaptic compartment and that their appropriate targeting and clustering in this region is critical for the formation and maintenance of excitatory synapses. The mechanisms of receptor insertion and removal at the postsynaptic membrane and of incorporation and maintenance in functional clusters within the postsynaptic density have been the topics of intensive research (Nusser, 2000; Savtchenko et al., 2000; Sheng, 2001; Franks et al., 2003). The interactions between AMPARs and many accessory proteins are of critical importance in these trafficking steps, and insertion and removal of synaptic AMPARs plays an important role in synaptic plasticity (Lu et al., 2001a). These interactors will be discussed later in the review.

GluR2/3 and GluR4 subunits colocalize throughout the postsynaptic density in the rat organ of Corti, with higher concentrations of receptors located around the periphery of the PSD. These subunits were not detected at extrasynaptic membranes, but some GluR4 subunits appeared to be presynaptic (Matsubara et al., 1996). This suggests that AMPARs are inserted into the postsynaptic membrane in a very precise manner and that receptor density increases upon moving away from the center of the synapse. In the rat hippocampus, it was estimated that there were 3 to 140 individual AMPAR present at synapses on CA3 pyramidal spines (Nusser et al., 1998). However, more recent investigations into the relationship between spine morphology and AMPAR distribution suggest that different types of spines contain differing amounts of AMPARs (Matsuzaki et al., 2001). In addition to the differential expression of AMPAR subunits within and between brain regions (McBain and Dingledine, 1993; Hack et al., 2001), AMPARs of different composition may be targeted to different synapses within a single cell (Rubio and Wenthold, 1997) or the distribution of AMPARs inside a neuron may be heterogeneous (Andrasfalvy and Magee, 2001).

It has been shown that the abundance of postsynaptic AMPARs correlates with both the size of the synapse and the dimensions of the dendritic spine head (Matsuzaki et al., 2004). These findings suggest that silent Schaffer collateral-commissural (SCC) synapses (see below) are smaller than the majority of SCC synapses at which AMPA and NMDARs are colocalized and that synapse size may determine important properties of SCC synapses (Takumi et al., 1999). Furthermore, NMDAR activation has been reported to cause the formation of new spines as well as synaptic delivery of AMPARs and perhaps is involved in the mechanism of LTP (Shi et al., 1999). Recently, it has been reported that the N-terminal domain of GluR2 increases spine size and density in hippocampal neurons suggesting that, in addition to being involved in rapid neurotransmission, GluR2 is important for spine growth and/or stability (Passafaro et al., 2003).

2. Extrasynaptic AMPA Receptors

Electrophysiological experiments indicate that AMPARs are widely distributed throughout the cell surface plasma membrane. However, antibody surface labeling of neurons indicates that surface-expressed AMPARs do not have a homogenous distribution. Typically, distinct immunopositive areas are observed that are thought to correspond to synaptic puncta. This discrepancy may be explained if nonsynaptic AMPARs are present at an insufficient density to be detected efficiently by immunocytochemistry.

Recent studies have focused on the mechanisms of receptor recruitment to the plasma membrane, incorporation of receptors into the synapse, and their clustering, both during synaptogenesis and synaptic plasticity (for example, see Cottrell et al., 2000; Andrasfalvy and Magee, 2004). This will be discussed in more detail in the trafficking sections below.

3. Presynaptic Terminal

The investigation into presynaptic AMPARs has not received much attention to date. Nonetheless, some years ago it was reported that AMPA increased glutamate release from rat hippocampal synaptosomes. This effect was shown to be related specifically to AMPARs and suggests that AMPARs are present on presynaptic terminals and that they may play a role in the regulation of neurotransmitter release (Barnes et al., 1994). It has also been shown that the movement of axonal filopodia is strongly inhibited by glutamate and requires the presence of axonal AMPA/ kainate glutamate receptors (Chang and De Camilli, 2001). Furthermore, functional GluR1 and GluR2 are expressed in axonal growth cones of hippocampal neurons (Martin et al., 1998; Hoshino et al., 2003), and a pool of presynaptic AMPAR subunits have also been isolated biochemically (Pinheiro et al., 2003; Schenk et al., 2003).

II. Trafficking of AMPA Receptors

A. Assembly

Each mature AMPAR is assembled from four individual subunits (Wu et al., 1996; Mano and Teichberg, 1998; Rosenmund et al., 1998; Safferling et al., 2001), although early work had indicated that the receptors may be pentamers (Ferrer-Montiel and Montal, 1996). Assembly is thought to occur through dimer pairing (Armstrong and Gouaux, 2000; Ayalon and Stern-Bach, 2001; Mansour et al., 2001; Robert et al., 2001). The early stages of assembly may be mediated by the proximal extracellular N-terminal domain of the subunits (Leuschner and Hoch, 1999; Ayalon and Stern-Bach, 2001; Horning and Mayer, 2004), but involvement of other regions, such as the membrane region and S2 portion, could also be necessary for formation of the mature tetrameric receptor (for differing viewpoints, see Wells et al., 2001; Pasternack et al., 2002).

Functional assembly of AMPAR subunits expressed in mammalian cells or Xenopus oocytes is selective, with no association with kainate or NMDAR subunits (Brose et al., 1994; Leuschner and Hoch, 1999), although coassembly with the orphan GluRδ2 with GluR1 and GluR2 has been reported (Kohda et al., 2003). The stoichiometry of the receptor complexes in these systems seems to be largely controlled by the expression levels of individual subunits, and it remains to be determined what processes govern assembly in neurons, especially since the type of complex can vary dramatically between synapses on a single neuron. Evidence that GluR2 is the preferred binding partner of GluR1 during heteromeric receptor assembly was uncovered by Mansour et al. (2001) in an elegant study involving physiological tagging of recombinant subunits and modeling of the results. They suggest that mature receptors are composed of a dimer of heteromers (i.e., that a GluR1/2 dimerizes with another GluR1/2), not a pair of homomers, and that they are arranged with identical subunits on opposite sides of the pore and not side by side, the stoichiometry and spatial arrangements of subunits affecting the phenotype. However, assembly of homomeric receptors is a stochastic process. Furthermore, recent studies in GluR2 knockout mice reported AMPAR complexes comprising abnormal heteromers of GluR1 and GluR3 as well as increased numbers of GluR1 and GluR3 homomers (Sans et al., 2003) with less efficient synaptic expression. This confirms that GluR2 is the preferred subunit partner in the assembly process and that it is important for synaptic expression of AMPARs.

There is considerable evidence that the subunit composition of functional AMPARs at specific synapses can change rapidly in response to synaptic activation (Shi et al., 2001; Liu and Cull-Candy, 2002; Lee et al., 2004), possibly due to targeted delivery of specific AMPAR complexes or subunit rearrangement of existing receptors in the spine. For example, it was observed that AMPARs containing only long C-terminal tails (i.e., GluR1) require plasticity-inducing synaptic activity for delivery to synapses, and those containing only short tails (i.e., GluR2/3) are constitutively expressed there (Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004). An attractive but as yet untested hypothesis is that binding of interacting proteins could favor the assembly of certain subunit combinations and prevent or disfavor others.

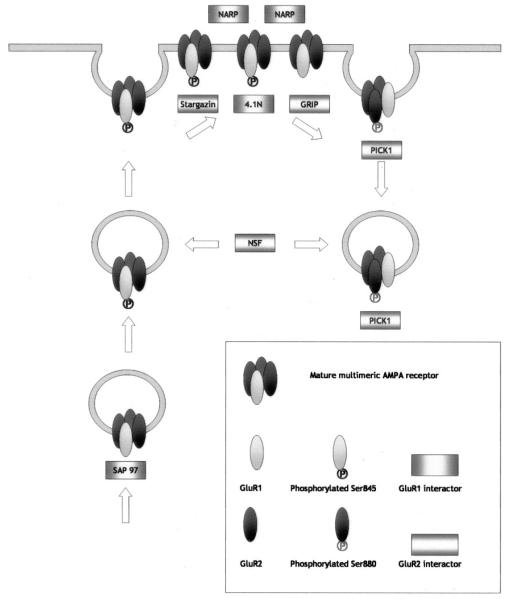

B. Visualizing AMPA Receptor Translocation

The isolation of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and its variants has enabled the experimenter to label cell structures and proteins for use in microscopy. For example, the morphology of neurons expressing GFP can be visualized using confocal microscopy, down to the shape and size of individual spines (Fig. 4). GFP-tagged AMPAR subunits may be expressed in neurons using a variety of techniques, and this approach has provided new insight into trafficking (Sheridan et al., 2002; Ashby et al., 2004), e.g., by viral transfer (Okada et al., 2001). For example, tetanic stimulation of hippocampal slice cultures causes the rapid NMDAR-dependent delivery of GFP-GluR1 into dendritic spines (Shi et al., 1999). GFP-labeled subunits have also been visualized in combination with electrophysiological tagging, where the channel rectification properties of recombinant AMPARs comprising specific subunits are altered by point mutations, e.g., GluR2 (R586Q)-GFP. Furthermore, expression of GFP-tagged AMPAR subunits in knockout mice has been used to “rescue” the wild-type phenotype, giving an insight into the cell biology of GluR1-containing heteromers (Mack et al., 2001). Using these approaches, it has been proposed that there are differential targeting mechanisms for AMPARs comprising either GluR1/GluR2 or GluR2/GluR3 subunit combinations (for example, see Hayashi et al., 2000). More specifically, GluR1/GluR2 receptors are added to synapses during plasticity via interactions between GluR1 and group I PDZ domain proteins, and CaMKII and LTP drive the synaptic expression of GluR1-containing AMPARs. In contrast, GluR2/GluR3 receptors replace existing synaptic receptors in a constitutive manner dependent on interactions between GluR2 with N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) and group II PDZ domain proteins (Shi et al., 2001; Malinow and Malenka, 2002).

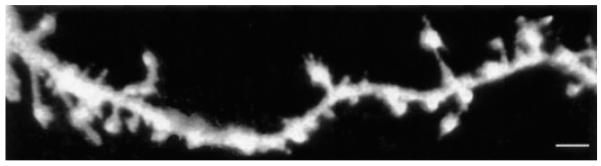

FIG. 4.

3D reconstruction of confocal image stack showing an area of spiny dendrite from a cultured pyramidal hippocampal neuron expressing a variant of GFP. The surface rendering of this reconstruction allows clear visualization of the varied structure of different spines (reproduced courtesy of Dr. M.C. Ashby, MRC Centre for Synaptic Plasticity, University of Bristol). Scale bar 4 μm.

Direct visualization of the intracellular transport of AMPARs using dispersed cultures of hippocampal neurons expressing GFP-GluR1 and GFP-GluR2 showed intracellular GFP-tagged AMPARs are widely distributed throughout the somatodendritic compartment (Perestenko and Henley, 2003). No evidence for intracellular clusters of receptors either in the soma or the dendrites was observed, suggesting the relatively free translocation of AMPARs in the soma and dendrites of neurons. AMPARs appear to be transported at rates comparable with fast axonal transport and move in a predominantly, but not exclusively, proximal to distal anterograde direction. Further data suggest that the intracellular transport of GFP-GluR1-containing AMPARs is not activity regulated but that various subunit combinations of the receptor complex are likely to be translocated throughout the soma and dendrites. Synapses may then “capture” these passing receptors as and when required (Perestenko and Henley, 2003). Furthermore, live imaging of GluR2 tagged with a pH-sensitive version of GFP that allows visualization of surface receptors only at the working (high) pH (pHlorin) demonstrated that extrasynaptic AMPARs containing the modified subunit react differently to the application of NMDA to synaptic receptors. The extrasynaptic receptors were internalized more quickly than those contained within the synapse (Ashby et al., 2004). This data confirms the model whereby extrasynaptic (or juxtasynaptic) receptors are more mobile than their synaptic counterparts, also demonstrated by particle tracking experiments (see below).

C. Lateral Diffusion of AMPA Receptors in the Membrane

Although the majority of interest in AMPAR dynamics has focused upon mechanisms of endo- and exocytosis, particularly with regard to plasticity, an increasing body of evidence suggests that diffusion within the postsynaptic membrane must account at least in part for some AMPAR movement (reviewed in Choquet and Triller, 2003). First, upon activation, AMPARs dissociate from their membrane anchors and diffuse away from the synapse prior to entering the constitutive endocytotic pathway, which is initiated either at the edge of the PSD or further afield in the extrasynaptic membrane (Zhou et al., 2001a). Second, studies involving stargazin suggest that the protein may recruit AMPARs from extrasynaptic to synaptic sites by binding synaptic PSD-95, then trapping freely diffusing AMPARs from outside the PSD (Chen et al., 2000; Schnell et al., 2002).

It is unsurprising that new research has centered on the kinetics of receptor movement during lateral diffusion in the neuronal plasma membrane. Interacting molecules outside, inside, and within the membrane can modulate receptor movement, and the subsynaptic cytoskeleton appears to be spatially organized into “corrals”, for example, rafts that limit diffusion of receptors within certain boundaries (Choquet and Triller, 2003).

Recently, innovative imaging methods involving single-particle tracking have permitted the study of the movement of a single AMPA receptor in the plasma membrane by the attachment of a specific fluorophore-conjugated antibody (Borgdorff and Choquet, 2002). GluR2-containing receptors appear confined to the regions surrounding the synapse, and their movement is controlled by basal neuronal activity. GluR2 diffusion ceased after influx of calcium, such as that observed after membrane depolarization, and the receptor appeared tethered. Increased Ca2+ levels may therefore change receptor binding to scaffolding proteins, stabilizing the receptor. This method was used to demonstrate that a proportion of AMPARs are able to exchange rapidly between synaptic and juxtasynaptic sites and that this diffusion is regulated (Tardin et al., 2003). This process may also be involved in synaptic plasticity mechanisms (Groc et al., 2004). While this study concentrated on the GluR2 subunit, tracking of other AMPAR species would be invaluable for establishing if differential movement took place in line with evidence gained from other studies (Passafaro et al., 2001; Shi et al., 2001).

D. AMPA Receptor Delivery to Synapses

The mechanisms by which AMPARs are brought to and inserted at the postsynaptic membrane represent a major research interest for many workers in the field. In particular, the activity-dependent components of this regulation which underlie changes in synaptic plasticity are an intensely studied area of neuroscience. In essence, there are two basic processes by which AMPARs could be delivered to the correct postsynaptic location: direct exocytosis of receptors to the site of action, or insertion into the membrane at a separate location with subsequent diffusion to the PSD. In fact, evidence to date suggests that both mechanisms can occur.

Single-particle tracking and video microscopy of the lateral membrane mobility of native AMPARs containing GluR2 in rat-cultured hippocampal neurons revealed that AMPARs alternate between rapid diffusive and stationary behavior. In older neurons, the stationary periods increased in frequency and length and were usually associated with synaptic sites. Increasing intracellular calcium causes rapid receptor immobilization and local accumulation on the surface, suggesting that calcium influx can inhibit AMPAR diffusion and that lateral receptor diffusion to and from synapses is important for the regulation of receptor numbers at synapses (Borgdorff and Choquet, 2002; Choquet and Triller, 2003). Using different methods, it has also been reported that surface insertion of GluR1 occurs slowly in basal conditions and is stimulated by NMDA receptor activation, whereas GluR2 exocytosis is constitutively rapid. In addition, GluR1 and GluR2 show different spatial patterns of surface accumulation, consistent with GluR1 being inserted initially at extrasynaptic sites and GluR2 inserted more directly at synapses (Passafaro et al., 2001; Gomes et al., 2003; Sheng and Hyoung Lee, 2003).

E. AMPA Receptor Turnover at Synapses

In the past, it was generally accepted that AMPARs within the postsynaptic membrane are relatively static, at least under basal conditions, with a constitutive turnover of surface-expressed receptors in the order of hours to days (Archibald et al., 1998; Huh and Wenthold, 1999). However, electrophysiological recordings predicted a more rapid emergence of AMPARs to the cell surface, such as that seen during the acquisition of AMPARs at silent synapses (Luscher et al., 1999; Kim and Lisman, 2001). Evidence that receptor internalization may also occur with equal rapidity was initially gathered during experiments involving blockade of the GluR2-NSF interaction (Nishimune et al., 1998; Song et al., 1998). However, as set out below, it was discovered that GluR2-containing AMPARs undergo rapid NSF-dependent cycles of internalization and reinsertion into the postsynaptic membrane with a half-life in the order of a few minutes. The principle of rapid NSF-dependent recycling has also been extended to G-protein-coupled receptors via β-arrestins (Miller and Lefkowitz, 2001) and GABAA receptors via GABA receptor-activating protein (Kittler et al., 2001), suggesting that this may be an important general regulatory synaptic mechanism.

The involvement of AMPAR interactors in receptor cycling has now been extensively studied (Ehlers, 2000; Osten et al., 2000; Ehrlich and Malinow, 2004; Lee et al., 2004; Nakagawa et al., 2004) and has had major implications for understanding the cellular processes underlying synaptic plasticity (for review, see Collingridge and Isaac, 2003; Collingridge et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2004). The application of glutamate to cultured hippocampal neurons causes a significant reduction in AMPARs, but not NMDARs from synaptic sites (Lissin et al., 1999), supporting the hypothesis that dynamic movement of AMPARs occurs in response to spontaneous synaptic activity. Subsequent work demonstrated that loss of AMPARs from synapses can also be promoted by NMDA, AMPA, insulin, or mGluR receptor activation (Carroll et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Snyder et al., 2001; Ehlers, 2003; Lee et al., 2004).

Several studies have focused on identifying the molecular basis of AMPAR cycling at the postsynaptic membrane. Increasing synaptic activity has been shown to cause a decrease in the number of surface-expressed AMPARs and size of AMPAR clusters in cultured neurons (Lissin et al., 1999). The internalization of GluR2-containing AMPARs and subsequent targeting for lysosomal degradation can be triggered by NMDA receptor activation and is mediated through the formation of clathrin-coated pits (Carroll et al., 1999; Ehlers, 2000; Lee et al., 2004). Furthermore, GluR2-containing receptors are internalized and recycled in response to the application of AMPA (Lee et al., 2004), but probably only in a subset of synapses as miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents decrease in frequency but not size (Carroll et al., 1999; Lissin et al., 1999; Beattie et al., 2000). GluR2 appears to be the dominant subunit when deciding the fate of internalized receptors, with GluR3 homomers being constitutively targeted to lysosomes and GluR1 homomers being continually recycled, and the GluR2-NSF interaction is important for the correct targeting of these receptors (Lee et al., 2004). These findings are in contrast to those of Ehlers, perhaps because of the different use of tetrodotoxin in these investigations (Ehlers, 2000; Lin et al., 2000). Similar results have also been reported for the effects of AMPA and insulin stimuli on the fate of internalized receptors (Lin et al., 2000).

F. Trafficking, Learning, and Memory

Changes in surface-expressed receptor populations are mirrored in LTD. Consistent with the synaptic loss of strength observed electrophysiologically, LTD, in part, is caused by the NMDA receptor-induced internalization of synaptic AMPARs (Carroll et al., 1999; Beattie et al., 2000) and shares a common mechanism with clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Man et al., 2000; Wang and Linden, 2000). It has also been shown that the clathrin adaptor protein (AP)2 associates with GluR2 in a similar region to that of NSF and is required for NMDA-dependent LTD (Lee et al., 2002b).

Research has also focused upon the intracellular signaling cascades that trigger the removal of AMPARs from the surface. NMDA-dependent LTD appears to require the activation of a calcium-dependent protein phosphatase cascade involving calcineurin and protein phosphatase I (PPI) (Lisman, 1989; Mulkey et al., 1993, 1994). Specific inhibition of calcineurin appears to block NMDA-dependent internalization as well as that which is observed after application of AMPA or insulin (Beattie et al., 2000; Ehlers, 2000; Lin et al., 2000). The situation is less clear when PPI is inhibited. Endocytosis has been reported to be both blocked (Ehlers, 2000) and enhanced after pharmacological inhibition of PPI (Beattie et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2000), although different techniques were employed in each set of experiments. More recently, roles for the small GTPases Ras, Rap, and Rab5 have been reported for AMPAR trafficking and synaptic plasticity. Both Rap and Rab5 are thought to mediate the activity-dependent removal of AMPARs during LTD expression, with Rap removing short-tail subunit-containing AMPARs and Rab5 involved in the clathrin-dependent removal of GluR1- and GluR2-containing AMPARs from synapses (Zhu et al., 2002; Brown et al., 2005). Conversely, Ras has a role in activity-dependent long-tail AMPAR insertion and may play a role in LTP (Zhu et al., 2002). Future work will no doubt focus on linking the induction mechanisms of synaptic plasticity to the functional up- or down-regulation of the AMPAR number at synapses.

A cellular mechanism for learning and memory was initially hypothesized by Bliss and Lomo (1973) who demonstrated that, in the rabbit hippocampus, repeated high frequency electrical stimulation resulted in a strengthening of synaptic transmission in target cells. This “long-term potentiation” of transmission after such a short period of stimulation was expressed as an experimental phenomenon in which “the coincident activation of a pre and postsynaptic neuron resulted in a long-lasting increase in synaptic strength” (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993). It was hypothesized that this endurance of transmission could be the underlying mechanism of learning and memory. The transition from observing such occurrences to unraveling the cellular mechanisms beneath them has led to a huge field of investigation, much of which centers on the modulation of synaptic AMPARs.

As already described, the synaptic expression of functional AMPARs is highly regulated both during development and by neuronal activity. Furthermore, an important characteristic of glutamatergic synapses is that they can exhibit NMDAR responses in the absence of functional AMPARs, and because of the magnesium block of NMDARs at resting membrane potentials, these postsynaptic membranes are functionally inactive or silent (Isaac et al., 1995; Liao et al., 1995). Silent synapses contain NMDARs but no AMPARs (Liao et al., 1999; Petralia et al., 1999; Pickard et al., 2000), and AMPARs can be recruited to these synapses within minutes by either spontaneous or stimulated NMDAR activation (Fitzjohn et al., 2001; Liao et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2001a; Pickard et al., 2001). The “unsilencing” of such synapses by the rapid insertion of functional AMPARs is likely to be a key determinant for NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity and neuronal development (Durand et al., 1996). The role of AMPAR trafficking in synaptic plasticity is a matter of intense investigation and has been reviewed extensively (Henley, 2003; Malenka, 2003; Sheng and Hyoung Lee, 2003). Aspects of current research are discussed elsewhere, since they relate to specific interacting proteins and phosphorylation events involved in exo- and endocytosis (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Simplified schematic diagram illustrating the protein interactions at GluR1 and GluR2 containing AMPA receptors.

III. Interacting Proteins

The regulation of AMPAR surface expression is undoubtedly a complex process that requires multiple protein interactions (Fig. 5). Many different proteins interact selectively with individual AMPAR subunits and can be divided into PDZ domain and non-PDZ domain-containing proteins (Ziff, 1997; Henley, 2003). Furthermore, a comparative study in macaques into the expression patterns of AMPARs and their interaction partners has addressed whether some of these interactions are relevant in higher mammals (Srivastava et al., 1998; Srivastava and Ziff, 1999).

A. PDZ-Containing Proteins

PDZ domains are modular protein interaction motifs that bind in a sequence-specific fashion predominantly to short C-terminal peptides, but also to internal peptides that fold into a β-finger or to other PDZ domains (reviewed in Sheng and Sala, 2001; Hung and Sheng, 2002). The acronym PDZ is derived from the three proteins first identified as containing this motif, namely PSD-95/SAP90, the Drosophila discs large tumor suppressor gene Dlg-A, and an epithelial tight junction protein ZO-1 (Woods and Bryant, 1991; Cho et al., 1992; Itoh et al., 1993). PDZ domain-containing proteins are characteristically involved in the assembly of supramolecular structures that can perform specific signaling tasks at particular cellular locations, for example, the subcellular targeting of receptor subunit complexes to the cell surface (for reviews, see O’Brien et al., 1998; Garner et al., 2000). The motif has been found both as a single domain and in a repeated format in different proteins (Ponting and Phillips, 1995; Songyang et al., 1997). Evidence of variable sequences encoding for amino acids lining the peptide binding groove of the domain reflects the diverse nature of PDZ interactions and their functional roles (Bezprozvanny and Maximov, 2001).

1. PDZ Architecture

PDZ domains exhibit a similar architecture throughout the range of proteins within which they are found (Doyle et al., 1996). Each PDZ domain binds only one ligand. A carboxylate-binding loop with the conserved sequence R/K-XXX-GLGF (X = any residue) ensures that the terminal carboxylate group of the peptide ligand is orientated in the correct fashion along the binding groove. Specific selectivity of PDZ motifs for different binding peptides is thought to be dependent upon small changes in the size and geometry of the hydrophobic pocket.

PDZ domains may be classified according to their specificity for C-terminal peptides. Each class of PDZ domain has been identified as recognizing a specific consensus sequence of the last four amino acids of the C-terminal peptide. Class I PDZ domains recognize either the sequence X-S/T-X-L or X-S/T-X-V, for example, the C terminus of NMDAR2a by PSD-95 (exact sequence E-D-D-V; Doyle et al., 1996). Class II domains recognize the sequence X- -X-

-X- where X = unspecified amino acid and

where X = unspecified amino acid and  = hydrophobic amino acid. Within this class are the PDZ domain-containing proteins GRIP and PICK1 which have both been shown to interact with the S-V-K-I sequence at the extreme C terminus of GluR2 (Dong et al., 1997; Dev et al., 1999).

= hydrophobic amino acid. Within this class are the PDZ domain-containing proteins GRIP and PICK1 which have both been shown to interact with the S-V-K-I sequence at the extreme C terminus of GluR2 (Dong et al., 1997; Dev et al., 1999).

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor treatment leads to an increase in expression of PDZ-containing AMPAR interactors SAP97, GRIP1, and PICK1 (Jourdi et al., 2003), and the control of GRIP expression by neurotrophins may be involved in light adaptation (Cotrufo et al., 2003). Although AMPARs don’t bind PSD-95 directly, this PDZ-containing protein can drive GluR1-containing AMPARs into synapses and is involved in LTP (DeSouza et al., 2002). Truncation of the last 10 amino acids of GluR2 removes the PDZ ligand and reduces synaptic incorporation of the receptor (Dong et al., 1999; Osten et al., 2000).

2. AMPA Receptor Binding Protein/Glutamate Receptor-Interacting Protein

ABP is a relative of GRIP and both proteins bind to the C terminus of GluR2/3 via a PDZ domain (Dong et al., 1997). This binding site is also shared by PICK1, and the interaction is differentially modulated by PKC/tyrosine kinase phosphorylation of Ser 880/Ser 876 within the ligand (Seidenman et al., 2003). ABP and GRIP, like SAP-97, have multiple PDZ domains and are major anchoring proteins in the postsynaptic density. Furthermore, ABP and GRIP can form homo- and heteromultimers via their PDZ domains (Srivastava et al., 1998; Fu et al., 2003). Blocking the ABP/GRIP interaction with GluR2 in cultured neurons did not affect surface targeting or constitutive recycling of the receptor, but prevented surface accumulation of the receptor over time (Osten et al., 2000) and reduces the amount of receptor internalized after AMPA stimulation (Braithwaite et al., 2002).

ABP exists as two splice variants, one short (containing six PDZ domains and known as ABP-S) (Srivastava et al., 1998; Dong et al., 1999) and one long (containing seven PDZ domains and called ABP-L) (Wyszynski et al., 1999). The long splice variant is sometimes confusingly referred to as GRIP2 and can be palmitoylated (to give pABP-L), which facilitates membrane and GluR2 association in spines (DeSouza et al., 2002). Its expression pattern was found to parallel AMPARs, and immunoreactivity was detected in the postsynaptic density and at synaptic plasma membranes (Gabriel et al., 2002). Interestingly, the nonpalmitoylated version of ABP-L is intracellular (Fu et al., 2003), which points to different sites of AMPAR anchoring according to the expression levels of the splice variants. In addition to this, ABP present on intracellular membranes can bind and retain GluR2 that has been internalized and can also prevent phosphorylation of GluR2 Ser 880 to stabilize this interaction (Fu et al., 2003). Immunocytochemistry studies demonstrated that ABP is predominantly expressed by pyramidal neurons of the neocortex, where it colocalizes with two thirds of GluR2/3-containing puncta in spines (Burette et al., 2001). A protein called KIAA1719 could be the human homolog of ABP, and studies into its expression in macaque brain suggest that overlapping distribution with GluR2/3-containing AMPARs may be restricted to particular areas of the forebrain and cerebellum, e.g., CA3 and dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Beneyto and Meador-Woodruff, 2004).

GRIP is predominantly expressed in GABAergic interneurons (Burette et al., 1999; Wyszynski et al., 1999), where ABP is expressed at lower levels and expression of these proteins is almost mutually exclusive in some synapses (Dong et al., 1999; Burette et al., 2001). Differential expression was also found in the retina (Gabriel et al., 2002). Furthermore, an interaction between GRIP and GABA receptor-activating protein implies a role for GRIP in GABAA receptor trafficking or stabilization (Kittler et al., 2004).

GRIP exists as a variety of splice variants to give long and short forms (Wyszynski et al., 1998). Full-length GRIP has seven PDZ domains, with the fourth and fifth domain being involved in GluR2/3 binding (Dong et al., 1997). Interestingly, two forms of GRIP, GRIP1-a and -b are thought to have different transcriptional start sites resulting in potential differential palmitoylation of the protein and hence membrane and protein interactions (Yamazaki et al., 2001). GRIP1b, the version that can be palmitoylated in heterologous cells, appears to be the dominant isoform in the forebrain and cerebellum and is soley associated with membranes. Confusingly, another GRIP splice variant, also called GRIP1-b and DLX-interacting protein, has been isolated as a truncated form of GRIP. This protein retains the PDZ domains necessary for AMPAR interaction, although one of these is required for its function as a transcriptional coactivator (Yu et al., 2001). Interestingly, this function can be blocked by activation of GluR2. Another isoform of GRIP, called GRIP1τ has also been isolated and acts as a testis-specific transcription factor (Nakata et al., 2004). GRIP1-c is a short isoform of GRIP containing only four PDZ domains, which can interact with GluR2/3 and is found concentrated in both GABAergic and glutamatergic synapses, although this protein can also be detected presynaptically (Charych et al., 2004).

GRIP protein is widely expressed in the brain throughout development and can be detected early in embryonic development, before the appearance of AMPARs (Dong et al., 1999). This is in contrast to the expression pattern of ABP, which parallels AMPARs (Dong et al., 1999). Indeed, Northern blotting demonstrated that mouse GRIP is down-regulated early in postnatal development (Wyszynski et al., 1998). GRIP is enriched in postsynaptic densities and is mostly associated with membranes throughout the neuron (Wyszynski et al., 1998), the intracellular version of the protein being associated with the rough endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus and recycling endosomes (Burette et al., 1999; Lee et al., 2001).

GRIP is a substrate for the Ca2+-dependent protease calpain, and activation of this enzyme disrupts the GluR2-GRIP interaction. Given that both LTP and LTD have calcium dependencies, activation of calpain and the subsequent effects on this interaction could play a role in these phenomena (Lu et al., 2001b).

Consistent with its role as a scaffolding protein, GRIP itself can interact with many other proteins. GRIP binding to Shank 2 could link AMPARs to mGluRs in the cerebellum (Uemura et al., 2004), although little colocalization was detected in retinal synapses (Brandstatter et al., 2004). An interaction with liprinα links GluR2/3-containing AMPARs to receptor tyrosine phosphatases, GTPases, and motor proteins and may therefore modulate receptor trafficking and clustering, the actin cytoskeleton, and synaptic maturation (Wyszynski et al., 2002; Ko et al., 2003). GRIP binding to GRIP-associated proteins link AMPARs to activity-dependent Ras signaling and trafficking events (Ye et al., 2000), as well as to the caspase pathway (Ye et al., 2002). The interaction with the Ephrin B receptor, a receptor tyrosine kinase, may be involved in LTP and recruitment of cytoplasmic GRIPs to membrane lipid rafts (Torres et al., 1998; Bruckner et al., 1999), and an interaction with kinesin heavy chain and microtubule-associated protein-1B may be involved in AMPAR trafficking (Setou et al., 2002; Seog, 2004). Furthermore, GRIP binding to the proteoglycan NG2 in immature glia could play a role in glial-neuronal signaling in the immature brain (Stegmuller et al., 2003), as well as diseases such as multiple sclerosis and melanoma (Stegmuller et al., 2002), and an interaction with Fras1 protein implicates GRIP in Fraser syndrome (Takamiya et al., 2004).

3. LIN-10

LIN-10 is a Caenorhabditis elegans membrane-associated guanlylate kinase (MAGUK) family protein. The human homolog, mLIN-10 or X11L can bind directly to GluR1 via a PDZ domain interaction and could direct trafficking of receptors containing this subunit (Stricker and Huganir, 2003). Interestingly, X11L can bind and modulate the activity of the transcription factor NF-κB and plays a role in Alzheimer’s disease (Tomita et al., 2000).

4. Protein Interacting with C Kinase

PICK binds to the C terminus of GluR2 at the synapse via a PDZ domain that is also required for PICK1 binding to active PKCα (Dev et al., 1999; Xia et al., 1999). The role of PICK1 binding to AMPARs may be to target this active PKC to the receptors (Perez et al., 2001), indeed, it is possible to differentiate between PICK1 binding to PKC and GluR2 (Dev et al., 2004). Phosphorylation of the PDZ ligand Ser 880 by PKC causes PICK1 to traffic to synapses and rapid internalization of GluR2-containing receptors, perhaps because this phosphorylation releases GluR2 from GRIP1 binding (Chung et al., 2000), but not PICK1. Similarly, phosphorylation of Tyr 876 in the PDZ ligand differentially affects the ability of GluR2 to bind ABP/GRIP and PICK1 (Hayashi and Huganir, 2004). The PKC-dependent internalization is implicated in cerebellar and hippocampal LTD (Matsuda et al., 2000; Xia et al., 2000; Kim et al., 2001; Seidenman et al., 2003), and PICK1 has been detected in recycling endosomes (Lee et al., 2001). However, overexpression of PICK1 in the hippocampus in vitro reduces the amount of synaptic GluR2, but not GluR1, and increases synaptic strength at resting potentials (Terashima et al., 2004). The PICK1-GluR2 interaction can itself be disassembled by NSF and other proteins (Hanley et al., 2002), and PICK is capable of interacting with at least an additional 13 proteins besides GluR2 (Meyer et al., 2004).

5. Synapse-Associated Protein-97

The SAP family of proteins are members of the MAGUK family that contain many protein interaction domains. These have undergone extensive investigation and are thought to have roles beyond anchoring and trafficking of transmembrane receptors (Fujita and Kurachi, 2000). SAP-97 is the mammalian homolog of the Drosophila protein discs large tumor suppressor protein, the human homolog of which is often called hDlg (Lin et al., 1997). SAP-97 expression is not restricted to the central nervous system, for example, the role of this protein in the heart and epithelium is of interest to many researchers (Godreau et al., 2003). In particular, the role of SAP-97 in cell-cell contact within epithelial tissues is an extensive area of study (Muller et al., 1995; Wu et al., 1998; Firestein and Rongo, 2001). Within the brain, the majority of SAP-97 may be detected at the postsynaptic density, but some of the protein can also be found cytoplasmically and presynaptically (Aoki et al., 2001); indeed, it has been shown that the protein plays a fundamental role in the architecture of synapses (Thomas et al., 1997). The very C terminus of GluR1 binds to the second PDZ domain of SAP-97 via an interaction that confers specificity to this particular AMPAR (Leonard et al., 1998; Cai et al., 2002a). This interaction potentially allows GluR1-containing AMPARs to associate with many other proteins including PKA, PKC and calcineurin, calmodulin (Paarmann et al., 2002), NMDARs (Bassand et al., 1999; Gardoni et al., 2003) and KARs (Mehta et al., 2001), stargazin (Ives et al., 2004), guanylate kinase-activating protein (Kuhlendahl et al., 1998; Wu et al., 2000), a kinesin superfamily motor protein (Mok et al., 2002), and the actin-based motor myosin VI, which plays a role in endocytosis (Wu et al., 2002; Hasson, 2003) provided that the interaction sites do not overlap. The interaction with SAP-97 also promotes the stabilization and synaptic incorporation of GluR1-containing AMPARs (Valtschanoff et al., 2000; Nakagawa et al., 2004). The Drosophila homolog of SAP-97, Dlg, with the cooperation of another protein called Strabismus promotes incorporation of proteins into newly formed plasma membrane (Lee et al., 2003b). SAP-97 is capable of multimerization with itself and other MAGUKs, which is consistent with a role as an anchoring protein (Karnak et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2002a; Feng et al., 2004) and controls synaptic targeting of AMPARS (Nakagawa et al., 2004). Synaptic targeting of SAP-97 is modulated by CamKII (Mauceri et al., 2004), and SAP-97 itself is a target for the kinase, which can modulate some interactions (Yoshimura et al., 2002; Gardoni et al., 2003). SAP-97 occurs as different splice variants (Mori et al., 1998; Godreau et al., 2003). Overexpression of the synaptic form increases the number of functional AMPARs at synapses (Rumbaugh et al., 2003) and can occlude LTP (Nakagawa et al., 2004), although NMDA-dependent internalization of GluR1 doesn’t involve SAP-97 (Sans et al., 2001). The SAP-97-A-kinase-anchoring protein 79 interaction promotes basal PKA phosphorylation of GluR1 Ser 845 and may be involved in the calcium-dependent dephosphorylation of this residue and hence LTD (Tavalin et al., 2002). Interestingly, blocking NMDARs leads to an up-regulation of SAP-97 expression in some areas of the cortex (Linden et al., 2001). Interaction with SAP-97 can occur early in the secretory pathway (Sans et al., 2001). SAP-97 has been implicated in cleft palate (Caruana and Bernstein, 2001), Alzheimer’s disease (Wakabayashi et al., 1999), and schizophrenia (Toyooka et al., 2002). SAP-97 also plays a role in trafficking of potassium channels (Kim and Sheng, 1996; Tiffany et al., 2000; Leonoudakis et al., 2001; Folco et al., 2004), plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases (DeMarco and Strehler, 2001; Schuh et al., 2003), the receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB4 (Huang et al., 2002), and interacts with tumor necrosis factor α-converting enzyme (Peiretti et al., 2003).

6. SemaF Cytoplasmic Domain-Associated Protein-3 and PDZ-Regulator of G-Protein Signaling-3

An interaction between the C terminus of GluR2 and SemaF cytoplasmic domain associated protein-3 (a protein with similar domains to E3 ubiquitin ligase LNX) and PDZ-RGS3 (PDZ-regulator of G-protein signaling-3, a GTPase-activating protein for trimeric G-proteins) has been reported in the yeast two-hybrid system, the functional implications of which are not clear (Meyer et al., 2004).

7. Syntenin

Syntenin is a protein that has been reported to interact with all AMPARs in vitro, but not in the yeast two-hybrid system. The affect of syntenin binding to AMPARs is not clear, but the interaction with KARs has been investigated (Hirbec et al., 2002, 2003). Syntenin is able to interact directly with the phosphatidylinositol biphosphate component of the plasma membrane (Zimmermann et al., 2002) and with syndecans, implicating them in cell-adhesion and synaptogenesis mechanisms (Zimmermann et al., 2001).

8. Transmembrane AMPA Receptor Regulatory Proteins

Stargazin was the first transmembrane interactor isolated for AMPARs (Chen et al., 2000) and is the only AMPAR interactor found associated with AMPARs in native gel preparations of cerebellar extracts (Vandenberghe et al., 2005). Null mutant mice exhibit the stargazer phenotype of absence seizures and cerebellar ataxia, which was attributed to the lack of functional AMPARs in cerebellar granule cells (Chen et al., 2000; Schnell et al., 2002). Stargazin is a member of a family of L-type calcium channel modulatory γ subunits and is also called γ-2. Stargazin, γ-3, γ-4, and γ-8 together form the transmembrane AMPAR regulatory protein family (Moss et al., 2003; Tomita et al., 2003). These proteins are differentially expressed throughout the nervous system, with γ-4 being predominant early in development (Tomita et al., 2003). Different TARPs may be expressed by the same neuron, but they do not form heteromeric complexes with each other. Furthermore, stargazin is the only TARP expressed by cerebellar granule cells (which explains the stargazer phenotype), and γ-8 has striking expression throughout the hippocampus, whereas stargazin is absent from CA1 (Tomita et al., 2003). This has implications for the differential control of activity-dependent trafficking events in different regions of the brain, for example, cerebellar and hippocampal LTD. TARPs comprise a conserved N-terminal AMPAR-binding domain and a more variable C-terminal PDZ binding domain that can bind to MAGUK proteins, for example, PSD-95 and PSD-93 (Dakoji et al., 2003). TARPs play a dual role in the trafficking of AMPARs, first enabling surface expression of AMPARs and second via interaction with PDZ proteins, facilitating synaptic incorporation of these receptors (Chen et al., 2000). The role of PSD-95 and stargazin in functional expression of AMPARs has been studied in the most detail, and it transpires that the TARP-MAGUK interaction can be regulated by phosphorylation of the PDZ binding site with phosphorylated stargazin being unable to bind PSD-95, resulting in a loss of synaptic AMPAR clusters (Chetkovich et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2002). Clustering of the tertiary complex is also regulated by the palmitoylation state of PSD-95, with activity-dependent depalmitoylation resulting in the loss of synaptic AMPARs (El-Husseini Ael et al., 2002). It has also been demonstrated that TARPs, unlike AMPARs, are stable at the plasma membrane and that agonist binding to AMPARs results in detachment from TARPs by an allosteric mechanism and internalization of the receptors (Tomita et al., 2004). The interaction between stargazin and PSD-95 also serves to link AMPARs to NMDARs and signaling cascades (Chetkovich et al., 2002; Lim et al., 2003; Mi et al., 2004). Other stargazin interactors include neuronal protein interacting specifically with TC10, which is enriched in the Golgi and is involved in trafficking of transmembrane proteins (Cuadra et al., 2004) and LC2, which is involved in microtubule trafficking events (Ives et al., 2004).

B. Other Interactors

1. Neuronal Activity-Regulated Pentraxin

Narp (neuronal activity-regulated pentraxin) is a neuronal intermediate-early gene product secreted upon synaptic activity (O’Brien et al., 1999). Narp is enriched in a subset of synapses within the hippocampus and spinal cord, but unlike other AMPAR interactors, Narp is extracellular and is believed to interact with the N terminus of AMPA subunits and can also form homomultimers. The protein is more predominant in presynaptic regions, with accumulation opposing excitatory synapses on dendritic shafts rather than on spines. Narp is postulated to promote aggregation of AMPARs via direct interaction, although in neuronal models this has only been demonstrated using exogenously applied Narp and dominant-negative mutant experiments (O’Brien et al., 1999, 2002). Interestingly, Narp secretion by hippocampal axons may selectively target the aggregation of AMPARs only in interneurons (Mi et al., 2002). Further research has shown that Narp may be involved in enduring forms of neuronal plasticity (Reti and Baraban, 2000).

2. N-Ethylmaleimide-Sensitive Factor