Abstract

Background

Breast and cervical cancer screening are widely recognized as effective preventive procedures in reducing cancer mortality. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of socioeconomic disparities in the uptake of female screening in Italy, with a specific focus on different types of screening programs.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted using data from the 2004-2005 national health interview survey. A sample of 15, 486 women aged 50-69 years for mammography and one of 35, 349 women aged 25-64 years for Pap smear were analysed. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the association between socioeconomic factors and female screening utilization.

Results

Education and occupation were positively associated with attendance to both screening. Women with higher levels of education were more likely to have a mammogram than those with a lower level (OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.10-1.49). Women of intermediate and high occupational classes were more likely to use breast cancer screening (OR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.55-2.03, OR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.40-1.91) compared to unemployed women. Women in the highest occupational class had a higher likelihood of cervical cancer screening compared to those in the lowest class (OR = 1.81; 95% CI = 1.63-2.01). Among women who attended screening, those with lower levels of education and lower occupational classes were more likely than more advantaged women to attend organized screening programs rather than being screened on the basis of their own initiative.

Conclusions

Inequalities in the uptake of female screening widely exist in Italy. Organized screening programs may have an important role in increasing screening attendance and tackling inequalities.

Background

Breast and cervical cancer have both high morbidity and mortality rates in Italy. In 2006, 36, 634 new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed and 11, 476 deaths were registered. In the same year 3, 418 new cases of cervical carcinoma were diagnosed, whereas 351 deaths due to cervical cancer and 2, 404 deaths due to cancer of the uterus not otherwise specified were recorded [1]. This disease burden can be reduced if cases are detected and treated early. Education helps people recognize early signs of cancer and seek prompt medical attention for symptoms, while screening programs, which include mammography for breast cancer, and Pap smear for cervical cancer, allow the early identification of cancer or pre-cancer before signs are recognizable [2].

Screening for breast and cervical cancer are strongly related with a reduction in cancer mortality [3]. Evidence-Based screening plans and European guidelines recommend a mammography every 2 years for women aged 50-69 and Pap test every 3 years for women aged 25-64 [4-6].

In Italy, in accordance to the National Health Plan, a National Plan for Prevention was developed to promote women's cancer screening. Cervical and breast cancer screening programs, promoted since the 90s, are developed at a regional level and offered free of charge to women of target age groups (25-64 for cervical cancer and 50-69 for breast cancer). Although participation rates generally increased in recent years, they were substantially lower than those recommended by international guidelines. In 2008, participation in organized screening programs was 40% and 55% for cervical cancer and breast cancer, respectively [6]. These figures are substantially lower than those set by the European guidelines of 85% and 70%, respectively [7].

Socioeconomic factors were shown to be strongly related to the use of preventive services [8-11]. Disparities in the utilization of female screening were widely identified [11-13]. Comparative studies on the use of preventive services in Europe showed inequalities in the participation to screening programs, although the size of the inequality varied among countries [14,15]. Women with lower health literacy are less likely to carry out routine cancer screening [16,17]. Ethnic minority, old age and low socioeconomic status are all accompanied by a low chance of undergoing cancer screening procedures [18].

In the US characteristics associated with lower rates of Pap test use included low family income and low educational attainment [19]; income and educational level were positively associated with mammography practice in a French population-based study [20].

Recent Italian studies generally focused on the effectiveness of screening programs [21,22]. Other Italian studies reported significant regional and educational inequalities [17,23].

This study aims to assess the association between socioeconomic status and the use of female cancer screening. A further objective was to evaluate whether socioeconomic factors are associated with adherence to organised screening programs versus opportunistic ones.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted using data from the National Survey on "Health conditions and health care services use", a five-yearly nationwide survey conducted by the Italian National Centre for Statistics (Istat) in December 2004-March 2005. Data were provided in an anonymised electronic dataset which is publicly available at Istat website [24]. Information was collected through face to face interviews and self-administered questionnaires. This analysis focused on women without self-reported history of cancer.

According to cancer screening guidelines the analysis was conducted on a subgroup of women aged 25-64 years for Pap smear and on a subgroup of women aged 50-69 years for mammography.

The survey contained the following questions: "Have you ever had a mammography/Pap test without having symptoms?"; "In case you had at least one mammography/Pap test, did you have other tests afterwards?"; "In case you had at least one mammography/Pap test, how often did you have the following tests afterwards?".

The frequency of screening practices was considered "appropriate" if women reported having a mammogram every 2 years and a Pap test every 3 years according to European guidelines [5,6]. For women aged 50-53 we considered as regular prevention having only one mammography, whereas for women aged 25-29 we considered as regular prevention having only one Pap test. With regards to the comparison between organized and opportunistic screening, we defined a dichotomous variable as whether or not a women reported having had Pap test or mammogram on invite of National Health Program at the most recent screening. This second analysis was performed on the subset of women who reported having an appropriate frequency of screening.

Demographic variables, such as age (from 50 to 69 for breast cancer screening and from 25 to 64 for cervical cancer screening), region of residence and marital status were considered as independent variables. Other independent variables considered were Body Mass Index (BMI), smoking status and self-assessed health status, because they were all found to be correlated to the use of female screening [25,26].

Educational level (primary school or less, secondary school, and high school and over) and occupational class (with the categories high, intermediate, low and non-working) were used as indicators of socioeconomic status. The non-working category included students, those unable to work, those in search of occupation, retired and housewives. In the breast cancer sample housewives were 86.5% of the "non-working" category, while in the cervical cancer sample they were 70.8% of the same category. Occupational class was classified according to the UK National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC) [27]. NS-SEC class was derived using the full derivation method based on the 1990 Standard Operational Classification (SOC) codes combining data on occupation and employment status (whether an employer, self-employed or employee; whether a supervisor, manager).

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study population. Separate multivariate logistic regression models were developed to examine the relationship between all explanatory variables and the outcomes of interest. For each final model, adjusted odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Sampling weights in all analyses were used, in order to reflect the multistage sampling design of the survey.

Results

Breast cancer screening

Table 1 describes the characteristics of the sample (N = 15, 486). About 43.4% of women lived in Northern Italy and 11, 310 women (73.0%) were married. About 50% of the sample reported a "fair" health status and only 8.5% a "bad" or "very bad" status. Approximately half had less than secondary school education and 38.2% was in the low occupational class. Women who underwent routine breast cancer screening were 47.0% of the sample. Table 2 shows prevalence rates of having regular screening by sample characteristics. Women with the highest level of education attended more frequently breast cancer screening than women with the lowest educational level (57.0% vs. 40.5%). There was a strong positive association between occupational class and attendance to breast cancer screening.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sample*

| Breast cancer screening | Cervical cancer screening | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 15, 486) | (N = 35, 349) | |||

| N | Proportion (%) | N | Proportion (%) | |

| Age groups | ||||

| 25-34 | 8746 | 24.7 | ||

| 35-44 | 10201 | 28.9 | ||

| 45-54 | 8677 | 24.5 | ||

| 55-64 | 7725 | 21.9 | ||

| 50-54 | 4184 | 27.0 | ||

| 55-59 | 4299 | 27.8 | ||

| 60-64 | 3426 | 22.1 | ||

| 65-69 | 3577 | 23.1 | ||

| Region of residence | ||||

| North-western Italy | 3599 | 23.2 | 12383 | 35.0 |

| North-eastern Italy | 3127 | 20.2 | 2355 | 21.5 |

| Central-Italy | 2833 | 18.3 | 6241 | 20.2 |

| Southern Italy | 4213 | 27.2 | 10405 | 29.4 |

| Italian Islands | 1714 | 11.1 | 3965 | 11.2 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1067 | 6.9 | 7257 | 20.5 |

| Married | 11310 | 73.0 | 23782 | 67.3 |

| Separated/Divorced | 914 | 5.9 | 2723 | 7.7 |

| Widowed | 2195 | 14.2 | 1587 | 4.5 |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Normal weight | 7564 | 48.8 | 22342 | 63.2 |

| Underweight | 305 | 2.0 | 1889 | 5.3 |

| Overweight | 5378 | 34.7 | 8128 | 23 |

| Obese | 2239 | 14.5 | 2990 | 8.5 |

| Self-assessed health status | ||||

| Good/Very good | 6414 | 41.4 | 22771 | 64.4 |

| Fair | 7751 | 50.1 | 11310 | 32.0 |

| Bad/Very bad | 1321 | 8.5 | 1268 | 3.6 |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Current | 2216 | 14.3 | 6474 | 18.3 |

| Former | 2565 | 16.6 | 5869 | 16.6 |

| Never | 10705 | 69.1 | 23006 | 65.1 |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary school or less | 7603 | 49.1 | 7082 | 20.1 |

| Secondary school | 3900 | 25.2 | 11214 | 31.7 |

| High school and over | 3983 | 25.7 | 17053 | 48.2 |

| Occupational class | ||||

| Non-working | 4941 | 31.9 | 9806 | 27.8 |

| Low | 5915 | 38.2 | 11643 | 32.9 |

| Intermediate | 3167 | 20.5 | 10223 | 28.9 |

| High | 1463 | 9.4 | 3677 | 10.4 |

| Mammography | ||||

| One every two years | 7274 | 47.0 | ||

| Less than two or none | 8212 | 53.0 | ||

| Pap test | ||||

| One every three years | 18417 | 52.1 | ||

| Less than three or none | 16932 | 47.9 | ||

*Italian National Health Interview Survey, 2004-2005 [24].

Table 2.

Prevalence rates of having regular mammography and Pap test by sample characteristics

| Women that performed a mammography every two years | Women that performed a Pap test every three years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age groups | ||||

| 25-34 | 3718 | 42.5 | ||

| 35-44 | 5482 | 53.7 | ||

| 45-54 | 5084 | 58.6 | ||

| 55-64 | 4133 | 53.5 | ||

| 50-54 | 2409 | 57.4 | ||

| 55-59 | 2038 | 47.6 | ||

| 60-64 | 1478 | 43.9 | ||

| 65-69 | 1349 | 38.1 | ||

| Region of residence | ||||

| North-western Italy | 1985 | 56.4 | 4795 | 63.1 |

| North-eastern Italy | 1959 | 62.7 | 5236 | 73.3 |

| Central-Italy | 1507 | 50.3 | 3753 | 60.1 |

| Southern Italy | 1308 | 29.3 | 3403 | 32.7 |

| Italian Islands | 515 | 28.1 | 1230 | 31.0 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 402 | 38.4 | 2739 | 37.7 |

| Married | 5608 | 49.8 | 13376 | 56.2 |

| Separated/Divorced | 419 | 46.1 | 1529 | 56.2 |

| Widowed | 845 | 38.2 | 773 | 48.7 |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Normal weight | 3732 | 49.8 | 11981 | 53.6 |

| Underweight | 156 | 50.0 | 945 | 50.0 |

| Overweight | 2451 | 45.7 | 4120 | 50.7 |

| Obese | 935 | 41.1 | 1371 | 45.9 |

| Self-assessed health status | ||||

| Good/Very good | 3087 | 48.7 | 11540 | 50.7 |

| Fair | 3690 | 47.5 | 6279 | 55.5 |

| Bad/Very bad | 497 | 37.5 | 598 | 47.2 |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Current | 1130 | 44.7 | 3452 | 49.0 |

| Former | 1407 | 54.8 | 3690 | 63.5 |

| Never | 4737 | 50.2 | 11275 | 53.9 |

| Level of education | ||||

| Primary school or less | 3052 | 40.5 | 3114 | 44.0 |

| Secondary school | 1951 | 49.5 | 5632 | 50.5 |

| High school and over | 2271 | 57.0 | 9671 | 56.7 |

| Occupational class | ||||

| Non-working | 1800 | 35.4 | 3598 | 63.3 |

| Low | 2788 | 47.9 | 6142 | 52.8 |

| Intermediate | 1863 | 59.5 | 6371 | 62.3 |

| High | 823 | 57.5 | 2306 | 62.7 |

Results of logistic regression models are shown in Table 3. Age, region of residence, marital status, education and social class were significant predictors of regular breast cancer screening after adjusting for the other covariates. Women of 55 years and older were less likely to have had a mammogram within the clinically recommended 2 year-time period. The likelihood to perform breast cancer screening was lower in central (OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.73-0.96) and southern (OR = 0.30; 95% CI = 0.26-0.34) than in northern regions. Married women resulted more likely to have regular prevention (OR = 1.83; 95% CI = 1.56-2.15). Women with a higher level of education were more likely to have a mammogram within the past 2 years than those with a lower level (OR = 1.28; 95% CI = 1.10-1.49). Women of intermediate and high occupational classes were more likely to use screening (OR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.55-2.03, OR = 1.63; 95% CI = 1.40-1.91) compared to the unemployed ones. Obese women had a lower likelihood to have a mammogram than normal weight ones (OR = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.77-0.98). Significant interactions were found between the highest educated and living in central and Southern Italy: as a result, educational inequalities were largest in Southern Italy and lowest in Central Italy.

Table 3.

Odds ratio of having regular prevention by mammography

| ORs (CI 95%) | Linearized standard errors | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | |||

| 50-54 | 1 | ||

| 55-59 | 0.64 (0.57-0.71) | 0.04 | < 0.001 |

| 60-64 | 0.58 (0.51-0.65) | 0.03 | < 0.001 |

| 65-69 | 0.47 (0.42-0.53) | 0.03 | < 0.001 |

| Region of residence | |||

| North-western Italy | 1 | ||

| North-eastern Italy | 1.30 (1.16-1.46) | 0.08 | < 0.001 |

| Central-Italy | 0.83 (0.73-0.96) | 0.06 | < 0.05 |

| Southern Italy | 0.30 (0.26-0.34) | 0.02 | < 0.001 |

| Italian Islands | 0.32 (0.27-0.37) | 0.02 | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 1 | ||

| Married | 1.83 (1.56-2.15) | 0.15 | < 0.001 |

| Separated/Divorced | 1.15 (0.93-1.43) | 0.13 | 0.206 |

| Widowed | 1.32 (1.10-1.60) | 0.13 | < 0.05 |

| Body mass index | |||

| Normal weight | 1 | ||

| Underweight | 0.88 (0.64-1.20) | 0.14 | 0.403 |

| Overweight | 1.04 (0.95-1.13) | 0.05 | 0.405 |

| Obese | 0.87 (0.77-0.98) | 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Self-assessed health status | |||

| Good/Very good | 1 | ||

| Fair | 1.17 (1.07-1.27) | 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| Bad/Very bad | 1.01 (0.86-1.17) | 0.08 | 0.957 |

| Cigarette smoking status | |||

| Never | 1 | ||

| Former | 1.11 (0.99-1.24) | 0.06 | 0.084 |

| Current | 0.95 (0.85-1.06) | 0.05 | 0.361 |

| Level of education | |||

| Primary school or less | 1 | ||

| Secondary school | 1.08 (0.97-1.19) | 0.05 | 0.147 |

| High school and over | 1.28 (1.10-1.49) | 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Occupational class | |||

| Non-working | 1 | ||

| Low | 1.23 (1.12-1.36) | 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| Intermediate | 1.77 (1.55-2.03) | 0.12 | < 0.001 |

| High | 1.63 (1.40-1.91) | 0.13 | < 0.001 |

| Interaction between Region of residence and Level of education | |||

| North-western Italy*Primary school or less | 1 | ||

| Central-Italy*High school and over | 0.77 (0.61-0.98) | 0.09 | < 0.05 |

| Southern Italy*High school and over | 1.38 (1.13-1.70) | 0.15 | < 0.001 |

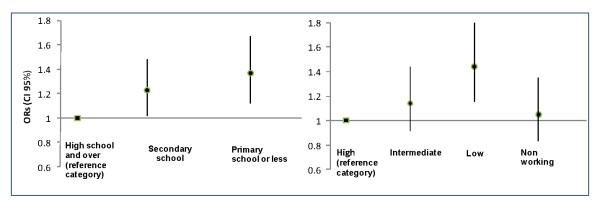

Figure 1 shows the ORs of attending an organized mammography screening program versus opportunistic screening by level of education and social class adjusting for age, regional residence, marital status, BMI, smoking status and self-assessed health status. The figure shows that women with lower educational level had a higher likelihood of attending an organized mammography screening program than more educated women (OR = 1.37; 95% CI = 1.12-1.67). In addition, low social class was associated with a greater use of organized screening program (OR = 1.44; 95% CI = 1.15-1.81) compared to a higher class.

Figure 1.

Odds Ratio of attending an organized mammography screening program versus opportunistic screening by level of education and social class adjusted for age, regional residence, marital status, BMI, smoking status and self-assessed status.

Cervical cancer screening

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 35, 349 women included in the study. About half of the sample had a high educational level (48.2%), only 10.4% were in the high occupational class, while there were not considerable differences in the percentages of non-working (27.8%), low (32.9%) and intermediate class (28.9%). More than 50% of women had a Pap test within the past 3 years.

A positive educational gradient was found for attendance to cervical cancer screening (Table 2). Attendance ranged from 56.7% among the highest educated to 44.0% among the lowest educated. Women in the low occupational class showed a lower attendance rate compared to the other occupational groups.

Results of logistic regression models are shown in Table 4. Women aged 35-64 years were more likely to undergo screening than women aged 25-34 years. A regional gradient was found in the regular uptake of cervical cancer screening: women living in Southern Italy and main islands, used Pap test less frequently than women living in North Italy with an OR of 0.38 (95% CI = 0.33-0.43) and an OR of 0.30 (95% CI = 0.27-0.34), respectively. Married women had a higher likelihood to have a Pap test (OR = 2.41; 95% CI = 2.23-2.60) than single women. Obese women reported a lower likelihood of cancer screening (OR = 0.77; 95% CI = 0.70-0.85) than normal weight ones. Former smoking status was an important predictor of regular Pap test attendance (OR = 1.36; 95% CI = 1.25-1.47). Women with a high socioeconomic status had a higher likelihood of cervical cancer screening compared to those with a lower status. The ORs were 1.91 (95% CI = 1.72-2.13) for women with a high school level or a higher level and 1.81 (95% CI = 1.63-2.01) for those with a high occupational class. The significant interaction terms in this model imply that higher levels of education in the South are less strongly associated with cervical cancer screening than in the rest of Italy.

Table 4.

Odds ratio of having regular prevention by Pap test

| ORs(CI 95%) | Linearized standard errors | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | |||

| 25-34 | 1 | ||

| 35-44 | 1.21 (1.12-1.31) | 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| 45-54 | 1.62 (1.49-1.77) | 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| 55-64 | 1.45 (1.32-1.60) | 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| Region of residence | |||

| North-western Italy | 1 | ||

| North-eastern Italy | 1.65 (1.52-1.80) | 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| Central-Italy | 0.87 (0.80-0.95) | 0.04 | < 0.05 |

| Southern Italy | 0.38 (0.33-0.43) | 0.03 | < 0.001 |

| Italian Islands | 0.30 (0.27-0.34) | 0.02 | < 0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 1 | ||

| Married | 2.41 (2.23-2.60) | 0.09 | < 0.001 |

| Separated/Divorced | 1.69 (1.50-1.90) | 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Widowed | 1.78 (1.54-2.07) | 0.14 | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index | |||

| Normal weight | 1 | ||

| Underweight | 0.98 (0.87-1.12) | 0.04 | 0.790 |

| Overweight | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) | 0.08 | < 0.05 |

| Obese | 0.77 (0.70-0.85) | 0.06 | < 0.001 |

| Self-assessed health status | |||

| Good/Very good | 1 | ||

| Fair | 1.22 (1.14-1.29) | 0.04 | < 0.001 |

| Bad/Very bad | 1.10 (0.95-1.28) | 0.07 | 0.206 |

| Cigarette smoking status | |||

| Never | 1 | ||

| Former | 1.36 (1.25-1.47) | 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Current | 1.10 (1.03-1.18) | 0.05 | < 0.05 |

| Level of education | |||

| Primary school or less | 1 | ||

| Secondary school | 1.44 (1.31-1.59) | 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| High school and over | 1.91 (1.72-2.13) | 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Occupational class | |||

| Non-working | 1 | ||

| Low | 1.28 (1.19-1.38) | 0.05 | < 0.001 |

| Intermediate | 1.73 (1.60-1.89) | 0.07 | < 0.001 |

| High | 1.81 (1.63-2.01) | 0.10 | < 0.001 |

| Interaction between Region of residence and Level of education | |||

| North-western Italy*Primary school or less | 1 | ||

| Southern-Italy*Secondary school | 0.78 (0.66-0.91) | 0.06 | < 0.05 |

| Southern Italy*High school and over | 0.83 (0.72-0.96) | 0.06 | < 0.05 |

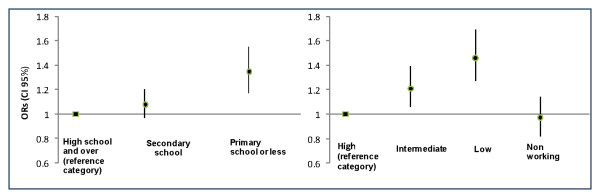

Figure 2 shows the OR of attending an organized cervical cancer screening program versus opportunistic screening by level of education and social class adjusting for age, regional residence, marital status BMI, smoking status and self-assessed health status. The lowest educated women had a higher likelihood of using organized screening than those with a higher educational level (OR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.17-1.55). Women of lower occupational class had a higher odds of organized screening program attendance compared with women in the highest occupational class (OR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.27-1.69).

Figure 2.

Odds Ratio of attending an organized cervical cancer screening program versus opportunistic screening by level of education and social class adjusted for age, regional residence marital status, BMI, smoking status and self-assessed status.

Discussion

In our study, we investigated inequity in breast and cervical cancer screening among Italian women. Our study suggests the presence of important inequalities in the use of these preventive services: both lower level of education and occupational class are strongly associated with underutilization of screening, despite coverage of most expenses for such preventive services by the Italian National Health System. However, among women who attended screening, those with lower level of education and lower occupational class were more likely to attend organized screening program rather than being screened on the basis of their own initiative.

These findings are consistent with the results of other international studies [8,13,28-30] reporting that women with lower socioeconomic status are less likely to undergo cancer screening. Sabates and Feinstein investigated the role of education in the uptake of cervical cancer screening in Britain; they found that continuing adult learning has a direct impact on the uptake of preventative screening which is not reduced by income, occupation or social class [31]. Furthermore, Rakowski et al. highlighted the positive influence of education on preventive behaviours [32]. Recently, a study on the use of breast and cervical cancer screening among European countries found that inequalities existed in some countries and were related to the type of screening program [14]. Contextual effects may also be important: it was shown that less educated women living in metropolitan areas with a lower proportion of low-education residents are less likely to undergo cancer screening, compared to women with similar level of education in other metropolitan areas. This may be due to socioeconomic factors or to the lack of culturally appropriate and accessible preventive health care services in the areas in which women live [16]. On the other hand, Achat et al. in 2005 demonstrated the existence of a weak association between socioeconomic status and regularity of mammography among Australian women when preventive programs were available without direct charge [33].

Referring to the relationship between socioeconomic status and adherence to organized screening programs versus opportunistic screening, our results are in line with several studies showing that women who attended an organized breast cancer screening program were more likely to be of a lower socioeconomic status [20,34]. These studies suggested that screening programs appeared to attract disadvantaged women who did not usually undergo screening. Similarly, a national study reported lower participation in organized screening program in more educated women, which was thought to reflect the greater extent of private purchase of screening outside public services [35]. In their study on the influence of type of screening program on the extent of inequality in some European countries, Palencia et al. reported large inequalities in countries without population-based cancer screening programs [14].

In contrast, other studies reported that organized screening programs assure a generic positive effect on coverage without clearly reducing the social gap [15,30,36,37]. More recently, results from two studies seemed to confirm that it is necessary to give programs longer periods of time since their start in order to observe any impact on inequalities [38,39].

In our study, we found that the association between socioeconomic status and mammography uptake was stronger for occupational status than for education. Women who do non-working were the most disadvantaged. This finding is similar to the one reported by Zackrisson et al. [40].

Our results show a positive association between female screening and marriage condition similar to other studies [33,41]. Being unmarried was a stronger predictor for not undergoing screening especially for Pap test. It may be that Pap test was often offered to married women as part of pre or post natal services [28]. In addition, according to Zackrisson et al. marital status could be considered as a proxy for social support [40].

Age was positively correlated to the uptake of Pap test whereas it was negatively correlated with the use of mammography. Conflicting findings are reported in the literature in this regard [42-44]. Higher rates found among older women for Pap smear may be due to a lower attention paid to preventive issues among younger generations.

We also considered the influence of BMI and smoking status on the use of preventive services. The role of obesity as a barrier to screening is a fairly recent research topic. This study reveals, as also shown by Datta [45], that women with BMI > 30 had a greater likelihood of non attending screening than women with normal weight. Cohen et al. discussed possible reasons for this association that were not necessarily weight-related, including embarrassment, discomfort and emotional barriers [46]. Results from a meta-analysis showed that obesity was inversely associated with the likelihood of having recently undergone a mammography [25].

In contrast with previous studies, our findings show that cigarettes smokers are not less likely that non smokers to use cancer preventive services [26,29]. Recently Ortiz et all found similar results, reporting that Pap screening was not associated with smoking status and other unhealthy behaviors [47]. We showed that former smokers tended to have higher attendance to screening than current smokers and people who were never smokers. This may be because former smokers decided to adopt a healthier lifestyle altogether. Similar results are reported by Rakowski et al. [48].

Despite the existence of free cancer prevention programs, the overall proportion of women that undertake regular screening tests is relatively small. Only half of the investigated women have had regular prevention, even though in Italy female screening programs have been existing for more than 10 years.

Deficit in utilization may be due to a lack of trust in the National Health Service and in its initiatives, as a consequence of the wide geographical heterogeneity in implementation of regional programs. Other reasons associated with poor adherence to screening may be the low perception in cancer screening efficacy, the fear of radiation mammography, the anxiety for the result and the fear of cancer.

In order to increase screening uptake rates, Duport et al. suggested that media campaigns should target women who were never screened or not regularly screened, underlying the importance of early diagnosis of breast cancer and the fact that screening is free of charge. On the other hand, benefits in terms of quality of organization about screening programs should be shown to women who underwent opportunistic mammography [20].

Our findings are subject to some limitations. First, there may be an effect of recall bias on self reported information about cancer screening practices: patients frequently tend to over-report their use of Pap test or mammogram and underreport the time lapse since their last screening [43,49].

Furthermore, several studies found that women's self-reported information varies according to the type of health care providers and to socio-demographic factors [50]. Secondly, useful information on some variables was not included in the survey questionnaire such as number of partners and parity.

A major strength of this study is that data were collected on a large national population-based sample. Furthermore, this sample provided detailed information about health status, socio-demographic characteristics and unhealthy behaviours.

In Italy, the 1998-2000 National Health Plan recommended that cancer screening programs should be introduced in every region [51]. Since 2005 the National Screening Observatory and the National Centre for Disease Control and Prevention have been working in partnership in order to control and support Regions in implementing screening programs.

Identifying reasons for failures of cancer screening is an important public health issue. In order to increase the proportion of women who carry out regular prevention it could be useful to improve the organization of screening services, for example through more flexible hours to meet the needs of women. Furthermore, it is important to involve the primary health sector to enhance and promote the spread of information on the benefits of screening to improve access to health services by increasing women compliance. Knowledge about socioeconomic status is essential for providing equal access to preventive care. Specific interventions at the national, regional and local level have to be designed in order to reduce disparities in screening utilisation by focusing on disadvantaged women. The implementation of organized screening programs may have an important role in increasing screening attendance and tackling socioeconomic inequalities.

Conclusions

Inequalities in the uptake of female screening widely exist in Italy. Organized screening programs may have an important role in increasing screening attendance and tackling inequalities.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

GD, FS and WR contributed to the conception of this paper; GD, BF and DB designed the study. DB, CBNAB, GMA and GN selected articles that met the inclusion criteria and extracted data. AR conducted the statistical analysis.

All authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of results and have read and approved the final version.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Gianfranco Damiani, Email: gdamiani@rm.unicatt.it.

Bruno Federico, Email: b.federico@unicas.it.

Danila Basso, Email: danila.basso@gmail.com.

Alessandra Ronconi, Email: aleronconi@tiscali.it.

Caterina Bianca Neve Aurora Bianchi, Email: caterinabianchi@hotmail.it.

Gian Marco Anzellotti, Email: g.anzellotti@gmail.com.

Gabriella Nasi, Email: gabrynasi@gmail.com.

Franco Sassi, Email: franco.sassi@oecd.org.

Walter Ricciardi, Email: wricciardi@rm.unicatt.it.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Saverio Tomaiuolo, Department of Health and Sport Sciences, University of Cassino, for his contribution in revising the manuscript.

References

- AIRTUM Working Group. Cancer trend (1998-2005) Epidemiol Prev. 2009;33(Suppl 1):1–167. http://www.registri-tumori.it/cms/ (accessed 14 January 2011) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2008-2013. 2008. http://www.who.int/entity/nmh/Actionplan-PC-NCD-2008.pdf (accessed 14 January 2011)

- Kerlikowske K, Grady D, Rubin SM, Sandrock C, Ernster VL. Efficacy of screening mammography. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;273(2):149–154. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520260071035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Prevention and Early DetectionWorksheet for Women. 2009. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/webcontent/acsq-009098.pdf (accessed January 2011)

- Perry N, Broeders M, de Wolf C, Törnberg S, Holland R, von Karska L. European guidelines for quality assurance in breast cancer screening and diagnosi. Luxembourg: European Commission. Office for Official publications of the European Communities; 2006. http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_projects/2002/cancer/fp_cancer_2002_ext_guid_01.pdf (accessed January 2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- I programmi di screening in Italia 2009. (Screening programs in Italy 2009) Osservatorio Nazionale Screening. http://ons.stage-zadig.it/sites/default/files/allegati/screening_cervice2009.pdf#overlay-context=it/content/i-rapporti-brevi-dell%25E2%2580%2599ons ; http://ons.stage-zadig.it/sites/default/files/allegati/screening_mammografia2009.pdf#overlay-context=it/content/i-rapporti-brevi-dell%25E2%2580%2599ons.

- Arbyn M, Anttila A, Jordan J, Ronco G, Schenk U, Segnan N, European guidelines for quality assurance in cervical cancer screenin. Luxembourg: European Commission. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lorant V, Boland B, Humblet P, Deliège D. Equity in prevention and health care. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56:510–516. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.7.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani G, Federico B, Bianchi CBNA, Ronconi A, Basso D, Fiorenza S. et al. Socioeconomic status and prevention of cardiovascular disease in Italy: evidence from a national health survey. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(5):591–596. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells KJ, Roetzheim RG. Health disparities in receipt of screening mammography in Latinas: a critical review of recent literature. Cancer Control. 2007;14(4):369–379. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido-Cumbrera M, Borrell C, Palència L, Espelt A, Rodríguez-Sanz M, Pasarín MI. et al. Social class inequalities in the utilization of health care and preventive services in Spain, a country with a national health system. Int J Health Serv. 2010;40(3):525–542. doi: 10.2190/HS.40.3.h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi F, Luft HS, Guadagnoli E. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in female breast cancer screening rates and stage diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2165–2172. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071761. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.07176. [published Online First: 31 October 2006] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser K, Patnick J, Beral V. Inequalities in reported use of breast and cervical screening in Great Britain: analysis of cross sectional survey data. BMJ. 2009;338:b2025. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2025. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2025 [published Online First: 16 June 2009] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palencia L, Espelt A, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Puigpinòs R, Pons-Vigués M, Pasarìn MI. et al. Socio-economic inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening practices in Europe: influence of the type of screening program. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(3):757–765. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirbu I, Kunst A, Mielck A, Mackenbach JP. Tackling Health Inequalities. Europe: an integrated approach - EUROTHINE. Final Report. Rotterdam: Erasmus MC; 2007. Educational inequalities in utilization of preventive services among elderly in Europe; pp. 483–499.http://survey.erasmusmc.nl/eurothine [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS, King J, Richards TB, Ekwueme DU. Cervical cancer screening among women in metropolitan areas of the United States by individual-level and area-based measures of socioeconomic status, 2000 to 2002. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(11):2154–2159. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamo C, Landriscina T, Vannoni F, Costa G. L'Indagine ISTAT e il Piano nazionale della prevenzione. Spunti per la definizione di target. (Italian National Institute of Statistics' survey and Italian National Prevention Plan. Consideration for target definition.) Approfondimenti sull'indagine Multiscopo Istat 2005. 2008;22(Suppl 3):143–160. Monitor. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerson K, Gretebeck K. Factors influencing cancer screening practices of underserved women. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(11):591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Devesa SS, Breen N. Cervical cancer screening among U.S. women: analyses of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Prev Med. 2004;39(2):270–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duport N, Ancelle-Park R, Boussac-Zarebska M, Uhry Z, Bloch J. Are breast cancer screening practices associated with sociodemographic status and healthcare access? Analysis of a French cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008;17(3):218–224. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3282b6fde5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puliti D, Miccinesi G, Collina N, De Lisi V, Federico M, Ferretti S. et al. Effectiveness of service screening: a case-control study to assess breast cancer mortality reduction. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(3):423–427. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi Rossi P, Chini F, Barca A, Baiocchi D, Federici A, Farchi S. et al. Efficacy of disease management profiles. The mammographicscreening program of Lazio. Tumori. 2008;94(3):297–303. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologna E. La prevenzione dei tumori femminili in Italia: il ricorso a Pap test e mammografia. Anni 2004-2005. Istat Statistiche in breve. 2006. pp. 1–12.

- Condizioni di salute e ricorso ai servizi sanitari Anni 2004-2005. (Health conditions and use of health services, 2004-2005) http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/5471

- Maruthur NM, Bolen S, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Obesity and mammography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):665–677. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0939-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Rakowski W, Ehrich B. Breast and cervical cancer screening: association with personal, spouse's, and combined smoking status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9(5):513–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Pevalin D. The National Statistics Socio-economic Classification: Genesis and Overvie. London: Office of National Statistics; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture MC, Nguyen CT, Alvarado BE, Velasquez LD, Zunzunegui MV. Inequalities in breast and cervical cancer screening among urban Mexican women. Prev Med. 2008;47(5):471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.005. [published Online First: 15 July 2008] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvin E, Brett KM. Breast and cervical cancer screening: sociodemographic predictors among White, Black, and Hispanic women. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(4):618–623. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.4.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duport N, Ancelle-Park R. Do socio-demographic factors influence mammography use of French women? Analysis of a French cross-sectional survey. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2006;15(3):219–224. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000198902.78420.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabates R, Feinstein L. The role of education in the uptake of preventative health care: the case of cervical screening in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(12):2998–3010. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.032. [published Online First: 5 January 2006] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Breen N, Meissner H, Rimer BK, Vernon SW, Clark MA. et al. Prevalence and correlates of repeat mammography among women aged 55-79 in the Year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achat H, Close G, Taylor R. Who has regular mammograms? Effects of knowledge, beliefs, socioeconomic status, and health-related factors. Prev Med. 2005;41:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamot E, Charvet A, Perneger TV. Overuse of mammography during the first round of an organized breast cancer screening programme. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(4):620–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato F, Bollani A, Spiazzi R, Soldo M, Pasquale L, Monarca S. et al. Factors associated with non-participation of women in a breast cancer screening programme in a town in northern Italy. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1991;45:59–64. doi: 10.1136/jech.45.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadea T, Bellini S, Kunst A, Stirbu I, Costa G. The impact of interventions to improve attendance in female cancer screening among lower socioeconomic groups: a review. Prev Med. 2010;50(4):159–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anttila A, Ronco G, Clifford G, Bray F, Hakama M, Arbyn M, Weiderpass E. Cervical cancer screening programmes and policies in 18 European countries. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(5):935–941. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luengo-Matos S, Polo-Santos M, Saz-Parkinson Z. Mammography use and factors associated with its use after the introduction of breast cancer screening programmes in Spain. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2006;15(3):242–248. doi: 10.1097/01.cej.0000199503.30818.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puddu M, Demarest S, Tafforeau J. Does a national screening programme reduce socioeconomic inequalities in mammography use? Int J Public Health. 2009;54(2):61–68. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-8105-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zackrisson S, Andersson I, Manjer J, Janson L. Non-attendance in breast cancer screening is associated with unfavourable socio-economic circumstances and advanced carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2004;108(5):754–760. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez MA, Ward LM, Pérez-Stable EJ. Breast and cervical cancer screening: impact of health insurance status, ethnicity, and nativity of Latinas. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):235–241. doi: 10.1370/afm.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambamoorthi U, McAlpine DD. Racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, and access disparities in the use of preventive services among women. Prev Med. 2003;37(5):475–484. doi: 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi V, Phillips SP, Hopman WM. Determinants of a healthy lifestyle and use of preventive screening in Canada. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:275. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SS, Leadbetter S, Richards T, Sabatino SA. Contextual analysis of breast and cervical cancer screening and factors associated with access among United States women, 2002. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(2):260–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta G, Colditz GA, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Individual-, neighborhood-, and state-level socioeconomic predictors of cervical carcinoma screening among U.S. black women. Cancer. 2006;106(3):664–669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SS, Palmieri RT, Nyante SJ, Koralek DO, Kim S, Bradshaw P. et al. Obesity and screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in women. A review. Cancer. 2008;112(9):1892–1904. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz AP, Hebl S, Serrano R, Fernandez ME, Suárez E, Tortolero-Luna G. Factors associated with cervical cancer screening in Puerto Rico. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A58. [Erratum appears in Prev Chronic Dis 2010;7(5)] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Clark MA, Ehrich B. Smoking and cancer screening for women ages 42-75: associations in the 1990-1994 National Health Interview Surveys. Prev Med. 1999;29:487–495. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon NP, Hiatt RA, Lampert DI. Concordance of self-reported data and medical record audit for six cancer screening procedures. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(7):566–570. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.7.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee SJ, Nguyen TT, Shema SJ, Nguyen B, Somkin C, Vo P. et al. Validation of recall of breast and cervical cancer screening by women in an ethnically diverse population. Prev Med. 2002;35(5):463–473. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piano Sanitario Nazionale 1998-2000. (Italian National Health Plan 1998-2000) http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_947_allegato.pdf [PubMed]