Abstract

Sexual assault and problem drinking are both prevalent in college women and are interrelated. Findings from cross-sectional research indicate that motives to drink to decrease negative affect (coping motives) or to increase positive affect (enhancement motives) are partial mediators of the sexual assault-problem drinking relation. However, no published longitudinal studies have examined these relations. The current study tests a longitudinal model and examines coping and enhancement motives as potential mediators. Participants were 131 female undergraduates who completed baseline measures of self-reported sexual assault victimization and problem drinking. Coping and enhancement motives were measured at three-month follow up; problem drinking was measured at six-month follow-up. Analyses using structural equation modeling (SEM) indicated direct and indirect paths in the sexual assault-problem drinking relation. Zero-order correlations indicated significant, positive relations between among drinking motives, sexual assault, and drinking variables. Longitudinally, mediation was evident for coping but not enhancement motives. Ultimately, findings were most consistent with self-medication hypotheses -- i.e., drinking in order to gain relief from symptoms or problems -- regarding the sexual assault-problem drinking relation.

Keywords: alcohol, sexual victimization, drinking motives, tension reduction, self-medication

I. Introduction

Important next steps in research on the relation between sexual assault and problem drinking include identifying mediators of the relation and testing models longitudinally. Motives for drinking alcohol as a means of regulating affect are promising candidates as mediators. Therefore, the current study tests a longitudinal model of the sexual assault-problem drinking relation, investigating coping and enhancement drinking motives as potential mediators.

Rates of sexual victimization among college women range are high (Abbey et al., 1996; Gidcyz et al., 2007; Gross, Winslett, Roberts, & Gohm, 2006). Moreover, sexual victimization is linked to increased alcohol and drug use (Collins, Ellickson, Orlando, & Klein, 2005; Corbin, Bernat, Calhoun, McNair, & Seals, 2001; Gidycz, Orchowsi, King, & Rich, 2008; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009). Despite this link, only recently have studies examined the relation’s directionality. Alcohol appears to increase risk of victimization (Combs-Lane & Smith, 2002; Greene & Navarro, 1998; Parks, Hsieh, Bradizza, & Romosz, 2008) and revictimization (Gidcyz et al,. 2007; Messman-Moore, Ward, & Brown, 2009). Victimization has also been associated with increased drinking; however, some studies have not found this relationship longitudinally (Messman-Moore et al., 2008; Najdowski & Ullman, 2009; Testa, Livingston, & Hoffman, 2007). Methodological differences may explain these disparate findings. Overall, results suggest bidirectional relationships between sexual victimization and drinking.

Drinking motives have been proposed as mediators of this relation. Specifically, victimization may be associated with higher endorsement of drinking to manage negative affect, which in turn leads to increases in drinking over time (self-medication). However, victimization could also lead to endorsement of drinking to increase positive affect – e.g., a woman who was victimized might drink because she simply wants to experience positive affect (see Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005). Both relationships have provisional support: drinking to cope and drinking to enhance mediated the relationship between trauma exposure and drinking outcomes in several studies of college students and community samples using cross-sectional designs (Goldstein, Flett, & Wekerle, 2010; Grayson & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2005; Miranda et al., 2002).

Testing mediation cross-sectionally, however, has limitations. Ideally, mediation models should evaluate predictor(s) assessed at one time point, followed by mediator(s) at a subsequent time point, followed by outcome(s) at a subsequent time point (Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998; Nock, 2007). Simultaneous assessment of either predictor and mediator; mediator and outcome; or all three contributes to causal ambiguity. Moreover, “true” tests of whether or not constructs function as mechanisms require that initial variables and mediators either be manipulated and/or measured at different time points from outcomes (see Kazdin & Nock, 2003; Nock, 2007). Thus, it is essential to test these relations using longitudinal designs, particularly because sexual assault and drinking motives do not readily lend themselves to experimental manipulations.

The current study tested coping and enhancement drinking motives as mediators of the sexual assault–problem drinking relation using a longitudinal design, with sexual assault history, drinking motives, and drinking variables assessed at different time points. We expected to find significant, positive relations between baseline sexual assault and problem drinking assessed six months later. We also expected to demonstrate that coping and enhancement drinking motives (assessed at three months) would function as mediators of the sexual assault-problem drinking relation.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were 131 female undergraduates. Their mean age was 18.65 years (SD =1.50). Fifty-one percent were Caucasian, 35% Asian American, 12% as American, Hispanic American, or bi/multi-racial, and 2% did not respond. A majority of the sample (93%) identified as heterosexual. Sixty-eight percent were freshman, 20% sophomores, 8% juniors, 2% seniors or above, and 2% did not respond. Three months and six months later, participants were contacted to complete a web-based follow-up survey.1 Neither the racial composition nor the mean age of the 3-month and 6-month follow-up changed significantly from baseline. Retention rates were 69% (n = 91) and 60% (n = 79) at 3-month and 6-month follow-up respectively. Participants who dropped out at either 3-month or 6-month follow-up did not differ from participants who did not drop out on baseline measures of sexual assault, alcohol consumption, or alcohol-related problems.

2.2 Measures

Alcohol consumption

Alcohol consumption was measured at six months with the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). Participants reported drinking patterns for a typical week over the last month. Alcohol consumption was calculated by summing the number of reported drinks for each day of the week.

Alcohol problems

Alcohol-related consequences were measured at six months by the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989). Two items were added related to drinking and driving. Participants were asked to report the number of alcohol consequences experienced over a three month time period. Alpha was .89.

Sexual assault

Unwanted sexual experiences since the age of 14 years old were measured at baseline with the modified version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (m-SES; Testa, VanZile-Tamsen, Livingston, & Koss, 2004). Items included attempted and completed vaginal, anal, and oral intercourse as well as sex under the influence of alcohol and drugs. For the current study, items involving forced touch were not included. Participants who had at least one event since the age of 14 years old were coded as sexual assault victims.

Coping and enhancement drinking motives

Drinking motives were measured at three months with the coping and enhancement subscales of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994). Alphas were .94 (enhancement) and .87 (coping).

2.3 Procedures

All procedures were approved by the University’s institutional review board. Participants were approached during a mass testing session and interested participants completed a brief screening questionnaire. Female participants who were at least 18 were invited via mail and email to participate in a six-month longitudinal study on problem drinking and sexual assault. Participants completed the baseline survey on the computer of their choice and informed consent procedures were completed online. Upon completion, participants received course credit for their introductory psychology class. Three- and six-month surveys were also completed online. Participants were compensated $20 (for three months) and $25 (for six months).

3. Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Sexual victimization was reported by 23% of the sample. Baseline sexual assault was positively and significantly correlated with coping and enhancement motives assessed three months later at time 2. Coping and enhancement motives assessed at time 2 were significantly and positively associated with drinks per week and alcohol-related problems assessed three months later at time 3.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for sexual assault, drinking motives, and drinking outcomes.

| Variable | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sexual assault (baseline) | 23% | -- | |||||

| 2. Coping (3 months) | 7.86 | 3.90 | .24* | -- | |||

| 3. Enhance (3 months) | 11.58 | 6.25 | .34** | .60*** | -- | ||

| 4. Drinks per week (6 months) | 2.80 | 4.61 | .42*** | .48*** | .41** | -- | |

| 5. Alcohol problems (6 months) | 2.10 | 3.87 | .52*** | .48*** | .47*** | .31** | -- |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Total N at baseline = 131 women. N’s vary due to missing data. Baseline sexual assault history was a dichotomous variable indicating whether or not participants had experienced an attempted or completed rape since the age of 14.

The proposed model was evaluated using AMOS 16. Missing data was addressed with full information maximum likelihood estimation (Shafer & Graham, 2002). Overall model fit was assessed with several fit indices, including chi-square, chi-square/df, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Normed fit index (NFI), and the comparative fit index (CFI (Bollen, 1989; Browne & Cudeck, 1993). A chi-square/df ratio less than 2.0 indicates good fit. RMSEA values less than .05 and NFI, and CFI values above .90 and close to 1.00 indicate good fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hoyle, 1995).

The proposed model evaluated coping and enhancement motives as mediators of prior sexual assault and subsequent problem drinking. Prior sexual assault was assessed at baseline, coping and enhancement drinking motives at three month follow up, and problem drinking at six month follow up. Problem drinking was modeled as a latent variable with drinks per week and alcohol-related negative consequences specified as indicators.

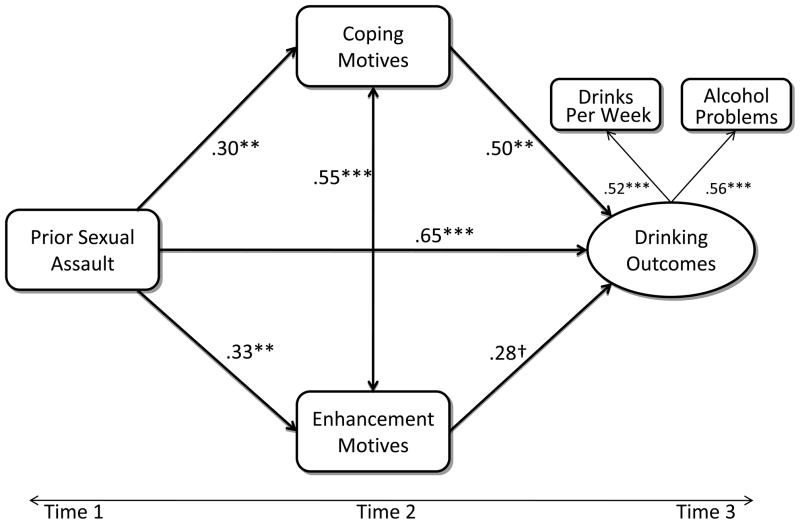

Figure 1 presents a diagram of the path model with standardized path coefficients. The proposed model provided an excellent fit to the data, χ2 (df = 2, N = 131) = 0.15, p = .927; χ2/df = .077; RMSEA = .000; NFI = .998; CFI = 1.000. Prior sexual assault was positively and significantly associated with both coping and enhancement motives and was directly associated with drinking outcomes. Coping motives were significantly associated with subsequent drinking outcomes whereas enhancement motives were marginally associated with drinking outcomes.

Figure 1.

Model of drinking motives as mediators of the association between prior sexual assault and subsequent problem drinking. Baseline was Time 1; Time 2 was three months later, and Time 3 was 6 months after baseline.

† p < .10. * p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p, .001.

Mediation analyses were conducted to evaluate whether coping motives and enhancement motives mediated the relation between prior sexual assault and subsequent problem drinking. MacKinnon and colleagues’ ab products of coefficients method was used (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). For the sexual assault → coping motives → problem drinking pathway way, the ab product was .82 (SE = .41, Z =1.98, p =.04). Thus, the indirect pathway from sexual assault to follow-up problem drinking through coping motives was significant. In contrast, the indirect pathway through enhancement motives was not significant, ab =.50 (SE = .30, Z =1.46, p =.15).

4. Discussion

This is the first study of which we are aware to evaluate drinking motives as mediators of the sexual assault problem drinking relation using a longitudinal design that is temporally consistent with the proposed mediation model. Findings support a direct, positive relationship between sexual assault and problem drinking. Coping motives also longitudinally mediated the relation between sexual assault and problem drinking. Enhancement motives were positively related to both sexual assault and problem drinking but mediation was not supported.

Overall, results are consistent with the notion that women who experience sexual assault engage in problem drinking behaviors due, in part, to a desire to reduce or manage distress. Thus, findings support self-medication and tension reduction theories (e.g., Greeley & Oei, 1999; Khantzian, 1985). However, we must note that we did not specifically measure psychological distress associated with victimization and cannot demonstrate this relationship directly. The lack of support for enhancement motives as a mediator was contrary to expectations and to findings in Grayson and Nolen-Hoeksema (2005). This difference may stem from the use of a cross-sectional design by Grayson and Nolen-Hoeksema. By retrospectively assessing sexual assault and concurrently assessing motives and drinking, the relationship between sexual assault, drinking motives and drinking behavior will artificially be strengthened due to the confound of time (Briere & Elliott, 1997). Thus, it is possible that the mediational findings with enhancement motives were a product of the design, rather than reflecting the true nature of the relationships between the variables. Another potential explanation could be that prior research examined relations between lifetime childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems, whereas our study investigated sexual assault since the age of 14. There may be qualitative differences between assault since the age of 14 versus assault at any point in childhood that explain the relative importance of coping and reduced importance of drinking-to-enhance.

These findings also may have important clinical implications. Our results suggest that modifying coping motives clinically could break or reduce the link between sexual assault and problem drinking. Improving coping skills may indirectly reduce problem drinking behaviors in this population. Furthermore, findings indicate that attempting to alter enhancement motives (e.g., brainstorming alternate activities for improving positive affect) may have less utility when intervening with clients who have experienced sexual assault.

4.1 Limitations and future directions

Study findings should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, this study cannot disentangle whether high drinking and high drinking motives predated the sexual assault, and whether women who drink more are at increased risk of victimization (see Combs-Lane & Smith, 2002; Greene & Navarro, 1998; Parks et al., 2008). Future studies should assess women prior to victimization and follow them over time. The sample was from a single university and it is unclear how results might generalize. Additionally, the present study focused exclusively on women; future research will be needed to evaluate whether findings extend to men. The present research is also limited by the exclusive use of self-report measures. Previous research has shown self-reported drinking to be unbiased relative to collateral reports (e.g., LaForge, Borsari, & Baer, 2005), and the SES is a widely-used, validated measure of sexual assault (e.g., Testa et al., 2004). Nevertheless, self-report measures are a limitation of the field. An additional limitation of this study was the relatively high attrition rate, particularly between baseline and 3-month follow-up. This may have been due in part to the disruption of the campus winter break which occurred between these two assessment periods, and it is noteworthy that there were no significant differences between drop-outs and completers in baseline measures of sexual assault or drinking.

Highlights.

We investigated the sexual assault-problem drinking relationship longitudinally.

We tested whether coping and enhancement drinking motives serve as mediators.

Sexual assault was directly and positively associated with problem drinking.

Coping and enhancement were positively related to sexual assault and drinking.

Mediation was supported for coping but not enhancement motives.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

This research was supported by K99AA017669, R00 AA017669, and the Small Grants Program at the University of Washington’s Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute. NIAAA and the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Participants were also invited to complete a brief survey two weeks following baseline to investigate the test-retest reliability of measures not reported here. One hundred and one participants completed the two-week follow-up survey.

Contributors

Dr. Lindgren designed the study, wrote the protocol, wrote the abstract and parts of the introduction and discussion, and edited all sections of the manuscript. Dr. Neighbors consulted on study design, conducted the analyses and wrote the first draft of the results section. Ms. Blayney was responsible for data management and wrote the first draft of the method section. Mr. Mullins also was responsible for data management, wrote part of the discussion section, and edited all sections of the manuscript. Dr. Kaysen consulted on study design, wrote part of the introduction, and edited all sections of the manuscript. All authors have contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kristen P. Lindgren, University of Washington

Clayton Neighbors, University of Houston.

Jessica A. Blayney, University of Washington

Peter M. Mullins, George Mason University

Debra Kaysen, University of Washington.

References

- Abbey A, Ross LT, McDuffie D, McAuslan P. Alcohol and dating risk factors for sexual assault among college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1996;20:147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Elliott DM. Psychological assessment of interpersonal victimization effects in adults and children. Psychotherapy: Theory, Practice, Research, Training. 1997;34:353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Neal DJ, Collins SE. A psychometric analysis of the self-regulation questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Klein DJ. Isolating the Nexus of Substance Use, Violence and Sexual Risk for HIV Infection Among Young Adults in the United States. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9:73–87. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-1683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs-Lane AM, Smith DW. Risk of sexual victimization in college women: The role of behavioral intentions and risk-taking behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Bernat JA, Calhoun KS, McNair LD, Seals KL. The role of alcohol expectancies and alcohol consumption among sexually victimized and nonvictimized college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2001;16:297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Gidycz CA, Loh C, Lobo T, Rich C, Lynn SJ, Pashdag J. Reciprocal relationships among alcohol use, risk perception, and sexual victimization: A prospective analysis. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:5–14. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.1.5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AL, Flett GL, Wekerle C. Child maltreatment, alcohol use and drinking consequences among male and female college students: An examination of drinking motives as mediators. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:636–639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson CE, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Motives to drink as mediators between childhood sexual assault and alcohol problems in adult women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:137–145. doi: 10.1002/jts.20021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeley J, Oei T. Alcohol and tension reduction. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological theories of drinking and alcoholism. 2. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 14–53. [Google Scholar]

- Greene D, Navarro RL. Situation-specific assertiveness in the epidemiology of sexual victimization among university women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1998;22:589–604. [Google Scholar]

- Gross AM, Winslett A, Roberts M, Gohm CL. An Examination of Sexual Violence Against College Women. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:288–300. doi: 10.1177/1077801205277358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A, Nock M. Delineating mechanisms of change in child and adolescent therapy: methodological issues and research recommendations. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2003;44(8):1116–1129. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Bolger N. The handbook of social psychology. 4. 1 and 2. New York, NY US: McGraw-Hill; 1998. Data analysis in social psychology; pp. 233–265. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of addictive disorders: Focus on heroin and cocaine dependence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1259–1264. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.11.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laforge RG, Borsari B, Baer JS. The utility of collateral informant assessment in college alcohol research: Results from a longitudinal prevention trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:479–487. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation Analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore T, Coates A, Gaffey K, Johnson C. Sexuality, substance use, and susceptibility to victimization: Risk for rape and sexual coercion in a prospective study of college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1730–1746. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Ward R, Brown AL. Substance use and PTSD symptoms impact the likelihood of rape and revictimization in college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:499–521. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Meyerson LA, Long PJ, Marx BP, Simpson SM. Sexual assault and alcohol use: Exploring the self-medication hypothesis. Violence and Victims. 2002;17:205–217. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.2.205.33650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najdowski CJ, Ullman SE. Prospective effects of sexual victimization on PTSD and problem drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:965–968. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock M. Conceptual and design essentials for evaluating mechanisms of change. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(Suppl 3):4S–12S. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks KA, Hsieh Y, Bradizza CM, Romosz AM. Factors influencing the temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and experiences with aggression among college women. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:210–218. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Livingston JA, Hoffman JH. Does sexual victimization predict subsequent alcohol consumption? A prospective study among a community sample of women. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2926–2939. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, VanZile-Tamsen C, Livingston JA, Koss MP. Assessing women’s experiences of sexual aggression using the Sexual Experiences Survey: Evidence for validity and implications for research. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Todd M, Armeli S, Tennen H, Carney MA, Ball SA, Kranzler HR, et al. Drinking to Cope: A Comparison of Questionnaire and Electronic Diary Reports. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:121–129. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]