Abstract

Objectives

The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) is a commonly used self-reporting tinnitus questionnaire. We undertook this study to determine the reliability and validity of the Chinese-Mandarin version of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI-CM) for measuring tinnitus-related handicaps.

Methods

We tested the test-retest reliability, internal reliability, and construct validity of the THI-CM. Two-hundred patients seeking treatment for primary or secondary tinnitus in Southwest China were asked to complete THI-CM prior to clinical evaluation. Patients were evaluated by a clinician using standard methods, and 40 patients were asked to complete THI-CM a second time 14±3 days after the initial interview.

Results

The test-retest reliability of THI-CM was high (Pearson correlation, 0.98), as was the internal reliability (Cronbach's α, 0.93). Factor analysis indicated that THI-CM has a unifactorial structure.

Conclusion

The THI-CM version is reliable. The total score in THI-CM can be used to measure tinnitus-related handicaps in Mandarin-speaking populations.

Keywords: Tinnitus, Reliability, Validity

INTRODUCTION

Tinnitus is a phantom auditory perception or sensation (1, 2). It is a common complaint with a prevalence of 10% to 15% in the adult population (3, 4). The mechanism and pathophysiology of tinnitus is poorly understood. Individuals affected with tinnitus can show an emotional distress and an may impact their quality of life. While some individuals feel depressed, angry, annoyed, distracted, or experience insomnia (5), tinnitus is not a significant problem for 80% of the people who have it (6, 7). It is important to identify the patients whose daily life is affected by tinnitus.

Assessing tinnitus is a challenging task. Tinnitus is primarily a subjective disorder. Self-reporting tinnitus questionnaires are one of the most commonly used tools for assessing the way patients experience tinnitus (8). Currently, there exist numerous questionnaires that are available to assess tinnitus in such manner. These include the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) (9), Tinnitus Severity Scale (10), Tinnitus Questionnaire (11), Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (12), Tinnitus Handicap Questionnaire (13), Subjective Tinnitus Severity Scale (14), Tinnitus Handicap/Support Scale (15), Tinnitus Coping Strategy Questionnaire (16), Tinnitus Coping Style Questionnaire (17), and Tinnitus Cognitions Questionnaire (18). Questionnaires used in research and in clinical practice are typically developed using a two-stage process. First, a questionnaire with a large set of questions is written. Then, through a pilot test, the statistical properties of the questions are examined and questions are selected from a set of questions to create the final questionnaire (19). These questionnaires must be reliable and valid. Reliability is an indication of how well the measured score reflects the true score. Validity is the degree to which the questionnaire score reflects the actual disability or handicap experienced by the respondent (19). THI is widely endorsed in clinical practice and has gained recognition as a useful self-reporting assessment tool for quantifying the impact of tinnitus on daily life (20). THI is brief enough to be used in busy clinics, is easy to administer and interpret, broad in scope, and psychometrically robust. It also has adequate internal consistency, reliability, convergent validity, and construct validity (9).

THI has been translated into a variety of languages, including Danish (THI-DK) (21), Spanish (22), Korean (23), Brazilian Portuguese (24), Turkish (25), Italian (26), and Singapore (27). Adequate reliability and validity have been demonstrated for all of these translations. THI has also been translated into Chinese-Cantonese (THI-CH) and researchers have reported good reliability and validity for this version, as well (28). Mandarin is the official language of China and is popularly used by people of the Han nationality. Cantonese is a dialect used in South China, including Guangdong Province, Guangxi Province, Hong Kong, and Macao. There are large differences between Mandarin and Cantonese. For example, Mandarin has 4 tones, while Cantonese has 6. There are also large differences in pronunciation and lexicon. Because of these differences, a THI-CM is needed. The purpose of the present study is to investigate whether THI-CM is a reliable and valid measure of tinnitus-related problems in the Mandarin-speaking tinnitus sufferers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

THI-CM development

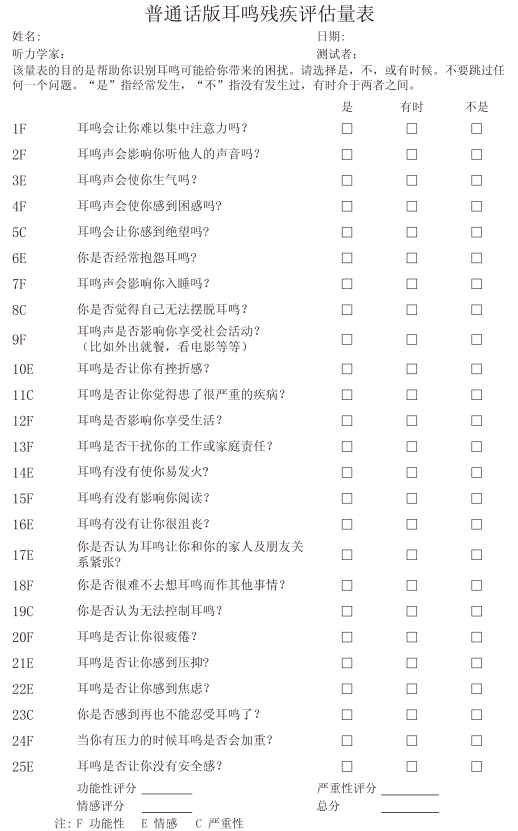

THI consists of 25 items grouped into 3 subscales. The subscales include the functional subscale (11 items), emotional subscale (9 items), and catastrophic subscale (5 items). The original version of the THI was translated into Mandarin Chinese using a translation-back translation method (29). In this translation, the translation of concepts was emphasized over a literal translation of the original THI. The original version of the THI was first translated into Mandarin Chinese by an audiologist, who is both an expert in tinnitus and is fluent in English. Then, a professional English translator, with no knowledge of the original THI, has back-translated the Mandarin version into English. The Mandarin version was then adjusted by the original translator, with the assistance of another audiologist, using comparisons between the original THI and the back-translated THI as a guide. The THI-CM was further refined, after initial testing with 25 tinnitus patients. Patient feedback was taken into account and adjustments were made to those questions that the majority of respondents found difficult to understand. The final THI-CM is in the Appendix (see http://e-ceo.org) to this report.

Subjects

Study participants were recruited from patients seeking treatment for primary or secondary tinnitus, at the West China Hospital Otolaryngology Department Hearing Center in Sichuan University. Subjects were enrolled after providing written informed consent and were assigned numbers corresponding to the order in which they were enrolled. Female patients were identified by numbers between 1 and 100, and male patients were identified by numbers between 101 and 200. This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the West China Hospital in Sichuan University.

Only patients with unilateral or bilateral tinnitus over 12 years of age were included in the study. Patients with psychiatric disorders or difficulty in expressing themselves were also excluded.

Study design

Subjects were asked to complete THI-CM by themselves. Then, hearing threshold and tinnitus match were tested for each subject. We used the Clinical Guide for Audiologic Tinnitus Management Method to determine the tinnitus match (30). Patients with an ID number that ended in 0 or 5 were asked to complete THI-CM a second time, 14±3 days, after the initial interview. Forty subjects completed THI-CM twice, and we used the resultant data to perform a test-retest reliability assessment.

Data analysis

SPSS ver. 11.5 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. External reliability was tested using test-retest reliability. Internal reliability was tested by determining Cronbach's α value. The construct validity was assessed using factor analysis.

RESULTS

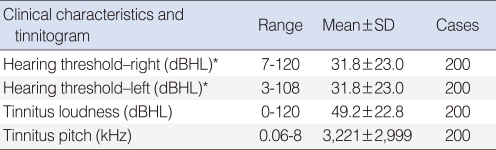

A total of 232 tinnitus patients were screened for inclusion in the study. Two-hundred patients, 100 women and 100 men, met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled. No patients withdrew from the study. The subjects ranged in age from 14 to 75 years of age (mean, 41.6; SD, 14.6). Patients suffered tinnitus for periods ranging from 0.03 to 240 months prior to the study, with a mean duration of 34.6 months (SD, 53.9). Eighty-three subjects had bilateral tinnitus, 54 had right ear tinnitus, and 63 had left ear tinnitus. The hearing threshold, tinnitogram and hearing loss of participants are shown in Tables 1, 2.

Table 1.

Hearing levels and psychoacoutics of tinnitus in study subjects

*Hearing threshold ranged from 0.25-8 kHz.

Table 2.

Distribution of study subjects according to degree of hearing loss

THI-CM score and severity

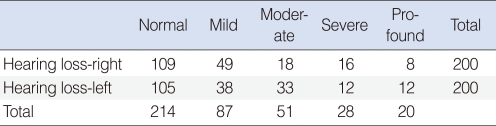

The mean scores of the functional, emotional, and catastrophic subscales were 20.1 (SD, 11.2), 15.2 (SD, 9.8), and 9.5 (SD, 5.8), respectively. The mean total score was 44.8 (SD, 24.5). The mean and standard deviation for each item in THI-CM are shown in Table 3. The mean total score and the subscale scores of THI-CM, THI-CH, THI-DK, and the original THI, as reported in their respective validation studies, are reported in Table 4. There were no statistically significant differences between men and women in any THI-CM score, including total score (P=0.76), functional subscale score (P=0.61), emotional subscale score (P=1.38), and catastrophic subscale score (P=1.05). Twenty-four subjects (12%) had no handicap, 63 subjects (31.5%) had a mild handicap, 48 subjects (24%) had a moderate handicap, and 65 subjects (32.5%) had a severe handicap.

Table 3.

Mean score and standard deviations for each THI-CM item

THI-CM, Chinese-Mandarin Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.

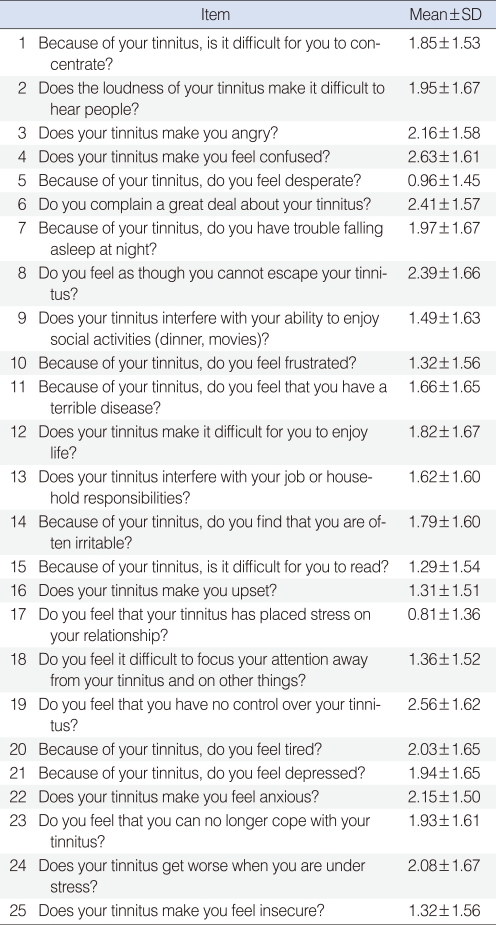

Table 4.

Score of total scale and subscales of THI-CM, THI-CH, THI-DK, THI original

Values are presented as mean±SD.

THI-CM, Chinese-Mandarin Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; THI-CH, Chinese-Cantonese THI; THI-DK, Danish THI.

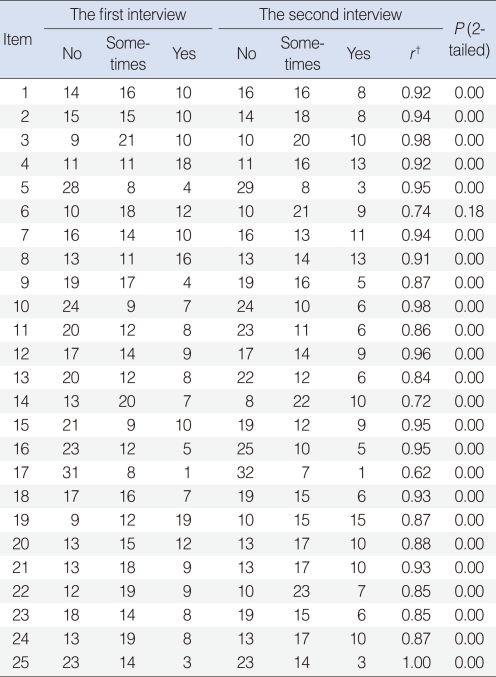

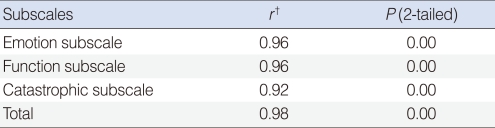

Reliability

The external reliability of THI-CM was examined by its test-retest reliability. Number of the subjects responded for each question at the first and second interview and the Pearson correlations between the first and second responses for each item are shown in Table 5. The Pearson correlation, between the first and second scores on the 3 subscales (emotional, functional, and catastrophic) and between the first and second total score, is presented in Table 6. The Pearson correlations ranged between 0.62 (item 17, "Do you feel that your Tinnitus has placed stress on your relationships with members of your family and friends?") and 1.00 (item 25, "Does your Tinnitus make you feel insecure?"). The Pearson correlations were greater than 0.85 for all items, except 6, 13, 14, and 17, for which the values ranged between 0.62 and 0.84. The Pearson correlation was greater than 0.90 for all subscales. The Pearson correlation for the total score was 0.98. These high Pearson correlation values indicate good test-retest reliability.

Table 5.

Subjects numbers for answering each question at the first and the second interview and correlations of THI-CM* (n=40)

THI-CM, Chinese-Mandarin Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.

*Pearson correlation.

Table 6.

External reliability* of the three subscales (emotion, function, catastrophic) and total items of THI-CM (n=40)

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

THI-CM, Chinese-Mandarin Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.

*External reliability was tested using Pearson correlation. †Pearson correlation.

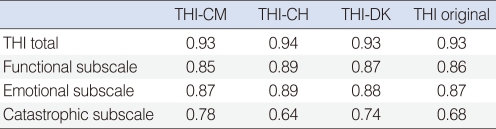

Cronbach's α for the total score was 0.93. The Cronbach's α coefficients for the functional, emotional, and catastrophic subscales were 0.85, 0.87, and 0.78, respectively. The total score and subscale Cronbach's α coefficients from the validation studies of THI-CM, THI-CH, THI-DK, and original THI are given in Table 7. The THI-CM has good external and internal reliability.

Table 7.

Internal reliability* of THI-CM, THI-CH, THI-DK, THI original version

*The internal reliability of THI was assessed using Cronbach alpha coefficients.

THI-CM, Chinese-Mandarin Tinnitus Handicap Inventory; THI-CH, Chinese-Cantonese THI; THI-DK, Danish THI.

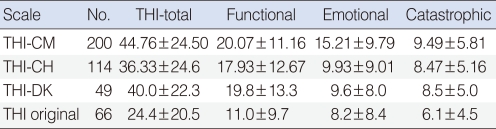

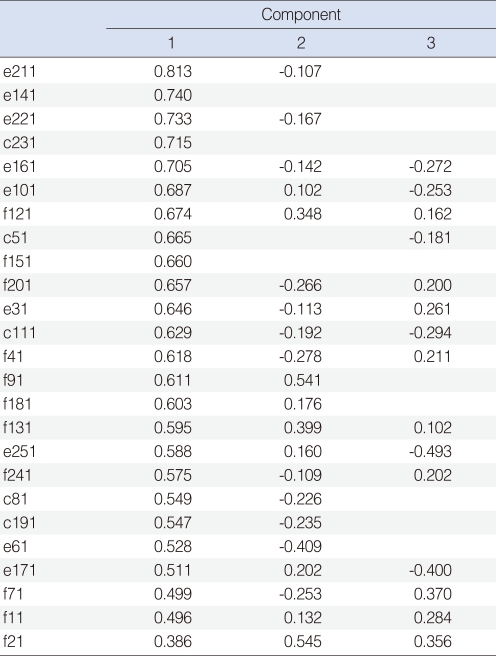

Validity

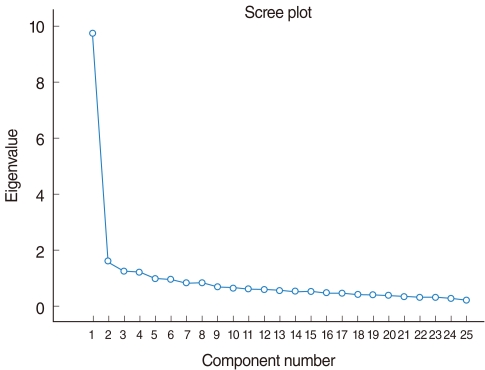

The validity was tested by construct validity. Factor analysis was used to demonstrate the construct validity. Because the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin sampling adequacy was 0.932, the items were considered acceptable for factor analysis. Principal component extraction was performed during factor analysis. Three factors (functional, emotional, and catastrophic responses to tinnitus) represent handicaps related to tinnitus. The eigenvalues for these factors were 9.7 (Factor 1), 1.6 (Factor 2), and 1.2 (Factor 3). Factor 1 explained 38.9% of the variance, Factor 2 explained 6.5% of the variance, and Factor 3 explained 5.0% of the variance. The cumulative variance explained by the 3 factors was 38.9%, 45.4%, and 50.4%, respectively. Loading scores for each item, except item 2, indicated almost exclusive loading on Factor 1. The item 2 ("Does the loudness of your tinnitus make it difficult to hear people?") primarily loaded on Factor 2, but also loaded on Factors 1 and 3 (Table 8). When an additional factor was added, the eigen values for the factors were 9.7 (Factor 1), 1.6 (Factor 2), 1.2 (Factor 3), and 1.2 (Factor 4). The added factor explained 4.8% of the variance and the total variance explained by the 4 factors was 55.2%. A scree plot indicated that adding factors would not improve the explanation variance (Fig. 1). Factor analysis indicated THI-CM has a unifactorial structure.

Table 8.

Component matrix of THI-CM

Extraction method: principal component analysis. 3 components extracted.

THI-CM, Chinese-Mandarin Tinnitus Handicap Inventory.

Fig. 1.

Scree plot of Chinese-Mandarin Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. The number of eigenvalue almostly reached to ten when one factor was introduced. However, it decreased dramatically when more than two factors were introduced.

DISCUSSION

THI-CM had good external reliability for the total score and the subscale scores (total Pearson correlation, 0.98, functional, emotional, and catastrophic Pearson correlations were 0.96, 0.96, and 0.92, respectively). Item 17 demonstrated the lowest degree of test-retest reliability. THI-CM showed high internal reliability, which is consistent with the reports for other versions. THI-CM had the same internal reliability as the original English version (α, 0.93). THI-CM and THI-CH also had similar internal reliability (α, 0.94 for THI-CH). The internal reliability of the functional (α, 0.85) and emotional (α, 0.87) subscales of THI-CM were similar to those of THI-CH (α, 0.89 and α, 0.89, respectively) and the original THI (α, 0.86 and α, 0.87, respectively). The catastrophic subscale had a relatively low degree of internal reliability (α, 0.78). However, only 5 items were included in such subscale. The small number of items may explain the relatively low degree of internal reliability of the catastrophic subscale. The internal reliability of the catastrophic subscale of THI-CM was higher than that reported for THI-CH and the original THI version (α, 0.64 and α, 0.68, respectively). However, the internal reliabilities of THI-DK, the Portuguese version, and the Italian version were high (α, 0.93, α, 0.929, and α, 0.91, respectively).

Originally, the THI subscales were examined on the basis of item content (9), rather than factor analysis. To assess the construct validity, the original THI developers used the Beck Depression Inventory, Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire, and symptom rating scales (9, 31, 32). Weak correlations were observed between THI and both the Beck Depression Inventory and Modified Somatic Perception Questionnaire. Significant correlations were observed between THI and symptom rating scales. The creators of the Portuguese, Italian, and Cantonese versions of THI evaluated validity by testing correlations between THI translations and other questionnaires. The Portuguese THI was correlated to the Beck depression inventory with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.68, thus, confirming its validity (24). The Italian version correlated well with the MOS 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) providing evidence of good construct validity (26, 33, 34). THI-CH scores significantly correlated with the anxiety and depression scores of the HADS (28). None of these researchers used uniform questionnaires to assess the correlations between THI and other questionnaires or psychoacoustical measures. Factor analysis of THI-CM yielded similar results to factor analyses performed on other versions of THI. Factor analysis demonstrated the unifactorial structure of THI-CM. Adding more factors did not improve the explanation of variance. Factor analysis of THI-DK (21), the Italianversion of THI (26), and THI-CH (28) also revealed unifactorial structures. In the validation study for THI-DK, researchers stated that the 3 factors only partially matched the items in the original 3 subscales (21). Factor analysis of the Italian version of THI indicated that the first extracted factor explained 35.9% of the variance and the second and the third factors explained 7.8% and 7.5% of the variance, respectively (26). The factor analysis of THI-CH demonstrated that the first factor explained 41.99% of the total variance and the second and the third factors explained 6.87% and 5.87% of the variance, respectively (28). Factor analysis of the original THI version done in 2003 indicated that 3 factors could explain 52.8% of the variance and adding more factors contributed little to the explanation of variance. Additionally, the majority of items loaded on the first factor (35). The unifactorial structure of the original version was demonstrated.

In the draft THI-CM used in the pilot study, some patients had difficulty interpreting the term "sometimes." In the final version, we added an explanation for this term at the beginning of THI-CM to help patients understand it.

The mean THI-CM total score and subscale scores were higher than those reported in the THI-CH validation study (Table 4). In this study, the subjects came from the areas in Southwest China, while the subjects in the THI-CH validation study came from Hong Kong. In terms of economic progress, Southwest China lags behind Hong Kong. Therefore, patients from Southwest China will not seek treatment unless they feel their tinnitus is severe. This reluctance to seek treatment may be an explanation of the observed higher score during THI-CM validation than that reported for THI-CH.

THI-CM does not appear to be affected by gender. The length to which the subjects in this study took was about 10 minutes to complete the questionnaire, and even those subjects with only a primary school education found it easy to understand. This self-administered questionnaire is therefore appropriate for busy clinics.

In conclusion, the THI-CM version is a reliable measure of tinnitus-related handicaps. The reliability of THI-CM is in line with that of the original English version. THI-CM has a unifactorial structure. It is culturally adapted to the Mandarin Chinese-speaking population, and its total score can be used to evaluate tinnitus-related handicaps and to assess the effect of tinnitus treatment and rehabilitation in such population. However, the subscales of THI-CM are not suitable for assessing tinnitus-related handicaps. Tinnitus-related handicaps included many aspects (irritation, annoyance, concentration, insomnia, etc). It is not possible to asses all aspects of tinnitus-related handicaps in one questionnaire. Therefore, additional questionnaires in Mandarin are still needed to further identify these aspects of tinnitus-related handicaps.

Appendix

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Jastreboff PJ, Hazell JW. A neurophysiological approach to tinnitus: clinical implications. Br J Audiol. 1993 Feb;27(1):7–17. doi: 10.3109/03005369309077884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moller AR. Tinnitus: presence and future. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:3–16. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(07)66001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henry JA, Dennis KC, Schechter MA. General review of tinnitus: prevalence, mechanisms, effects, and management. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005 Oct;48(5):1204–1235. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/084). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoffman HJ, Reed GW. Epidemiology of tinnitus. In: Snow JB, editor. Tinnitus: theory and management. Lewiston, NY: BC Decker; 2004. pp. 16–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Westin V, Hayes SC, Andersson G. Is it the sound or your relationship to it? The role of acceptance in predicting tinnitus impact. Behav Res Ther. 2008 Dec;46(12):1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis A, Refaie AE. Epidemiology of tinnitus. In: Tyler RS, editor. Tinnitus handbook. Sandiego, CA: Singular; 2000. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jastreboff PJ, Haell JW. Treatment of tinnitus based on a neurophysiological model. In: Vernon JA, editor. Tinnitus: treatment and relief. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 1998. pp. 201–217. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson PH, Henry JL. Psychological management of tinnitus. In: Tyler RS, editor. Tinnitus handbook. Sandiego, CA: Singular; 2000. pp. 263–280. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman CW, Jacobson GP, Spitzer JB. Development of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996 Feb;122(2):143–148. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1996.01890140029007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sweetow RW, Levy MC. Tinnitus severity scaling for diagnostic/therapeutic usage. Hear Instrum. 1990;41:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hallam RS. Manual of the tinnitus questionnaire. London: Psychological Co.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson PH, Henry J, Bowen M, Haralambous G. Tinnitus reaction questionnaire: psychometric properties of a measure of distress associated with tinnitus. J Speech Hear Res. 1991 Feb;34(1):197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuk FK, Tyler RS, Russell D, Jordan H. The psychometric properties of a tinnitus handicap questionnaire. Ear Hear. 1990 Dec;11(6):434–445. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halford JB, Anderson SD. Tinnitus severity measured by a subjective scale, audiometry and clinical judgement. J Laryngol Otol. 1991 Feb;105(2):89–93. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100115038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erlandsson SI, Hallberg LR, Axelsson A. Psychological and audiological correlates of perceived tinnitus severity. Audiology. 1992;31(3):168–179. doi: 10.3109/00206099209072912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry JL, Wilson PH. Coping with tinnitus: two studies of psychological and audiological characteristics of patients with high and low tinnitus-related distress. Int Tinnitus J. 1995;1(2):85–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Budd RJ, Pugh R. The relationship between locus of control, tinnitus severity, and emotional distress in a group of tinnitus sufferers. J Psychosom Res. 1995 Nov;39(8):1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson PH, Henry JL. Tinnitus cognitions questionnaire: development and psychometric properties of a measure of dysfunctional cognitions associated with tinnitus. Int Tinnitus J. 1998;4(1):23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyler RS. Tinnitus disability and handicap questionnaires. Semin Hear. 1993 Nov;14(4):377–384. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newman CW, Sandridge SA, Jacobson GP. Psychometric adequacy of the tinnitus handicap inventory (THI) for evaluating treatment outcome. J Am Acad Audiol. 1998 Apr;9(2):153–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zachariae R, Mirz F, Johansen LV, Andersen SE, Bjerring P, Pedersen CB. Reliability and validity of a Danish adaptation of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Scand Audiol. 2000;29(1):37–43. doi: 10.1080/010503900424589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baguley D, Norman M. Tinnitus handicap inventory. J Am Acad Audiol. 2001 Jul-Aug;12(7):379–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JH, Lee SY, Kim CH, Lim SL, Shin JN, Chung WH, et al. Reliability and validity of a Korean adaptation of the tinnitus handicap inventory. Korean J Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2002 Apr;45(4):328–334. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt LP, Teixeira VN, Dall'Igna C, Dallagnol D, Smith MM. Brazilian Portuguese language version of the "Tinnitus Handicap Inventory": validity and reproducibility. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006 Nov-Dec;72(6):808–810. doi: 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31048-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aksoy S, Firat Y, Alpar R. The Tinnitus Handicap Inventory: a study of validity and reliability. Int Tinnitus J. 2007;13(2):94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monzani D, Genovese E, Marrara A, Gherpelli C, Pingani L, Forghieri M, et al. Validity of the Italian adaptation of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory: focus on quality of life and psychological distress in tinnitus-sufferers. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2008 Jun;28(3):126–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim JJ, Lu PK, Koh DS, Eng SP. Impact of tinnitus as measured by the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory among tinnitus sufferers in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 2010 Jul;51(7):551–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kam AC, Cheung AP, Chan PY, Leung EK, Wong TK, van Hasselt CA, et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese (Cantonese) Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009 Aug;34(4):309–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.01946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradley C. Translation of questionnaires for use in different languages and cultures. In: Bradley C, editor. Handbook of psychology and diabetes: a guide to psychological measurements in diabetes research and management. Langhorne: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry JA, Zaugg TL, Schechter MA. Clinical guide for audiologic tinnitus management I: assessment. Am J Audiol. 2005 Jun;14(1):21–48. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2005/004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961 Jun;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Main CJ. The modified somatic perception questionnaire (MSPQ) J Psychosom Res. 1983;27(6):503–514. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(83)90040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993 Mar;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costantini M, Musso M, Viterbori P, Bonci F, Del Mastro L, Garrone O, et al. Detecting psychological distress in cancer patients: validity of the Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Support Care Cancer. 1999 May;7(3):121–127. doi: 10.1007/s005200050241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baguley DM, Andersson G. Factor analysis of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Am J Audiol. 2003 Jun;12(1):31–34. doi: 10.1044/1059-0889(2003/007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]