Abstract

Glomerulonephritis occurs as a rare form of renal manifestation in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Herein, we report a case of falciparum malaria-associated IgA nephropathy for the first time. A 49-yr old male who had been to East Africa was diagnosed with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Microhematuria and proteinuria along with acute kidney injury developed during the course of the disease. Kidney biopsy showed mesangial proliferation and IgA deposits with tubulointerstitial inflammation. Laboratory tests after recovery from malaria showed disappearance of urinary abnormalities and normalization of kidney function. Our findings suggest that malaria infection might be associated with IgA nephropathy.

Keywords: Glomerulonephritis, IgA nephropathy, Malaria, Plasmodium falciparum

INTRODUCTION

Malaria is one of the most common parasitic infection in tropical areas, and 243 million cases were reported worldwide in 2008 (1). Renal involvement is particularly common in Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium falciparum infections and is generally manifested as chronic progressive glomerulopathy in the former and acute kidney injury (AKI) in the latter (2). In endemic areas, AKI occurs as a complication of falciparum malaria, mostly caused by acute tubular necrosis (ATN) and/or interstitial nephritis, in 1% to 4.8% of native patients, and its incidence increases up to 25% to 30% in European patients. Another less common form of renal involvement in falciparum malaria is acute glomerulonephritis, which is characterized by mesangial proliferation and matrix expansion (3). To date, only IgM, IgG, and C3 deposits within the mesangium have been detected, and immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy associated with falciparum malaria has not yet been reported. Herein, we present a case of falciparum malaria-associated IgA nephropathy accompanied by AKI that was resolved after recovery from the malaria infection.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 49-yr-old Korean male visited our hospital on February 22, 2010 because of persistent fever for three days despite repeated use of antipyretics. The patient had a 6-yr history of diabetes and had been receiving treatment at our hospital. Clinical evaluations performed 2 months earlier showed serum creatinine level of 0.9 mg/dL [corresponding to estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 95.3 mL/min/1.73m2, calculated using the 4-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation] and random urine albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) of 42.5 mg/g without microhematuria. Serial urine analyses since the first visit to the clinic consistently showed no microscopic hematuria. Ophthalmologic evaluation revealed mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Two weeks before the illness, he traveled Uganda in East Africa.

Upon admission, the patient was dehydrated and lethargic. Blood pressure, pulse rate and body temperature were 110/60 mmHg, 98 beats/min and 38.3℃, respectively. Initial laboratory tests showed the following values: hemoglobin, 9.0 g/dL; platelets, 57 × 103/µL; serum creatinine, 1.8 mg/dL; aspartate/alanine aminotransferase, 101/90 U/L; total bilirubin, 6.0 mg/dL; prothrombin time international normalized ratio, 1.03. The patient tested negative for hepatitis B surface antigen, and anti-hepatitis C virus antibody. Urine dipstick examination showed microhematuria (2+) and proteinuria (2+). Spot urine protein-creatinine ratio (UPCR) and ACR were 2.92 g/g and 1,064 mg/g, respectively, and 24-hr urinary protein and creatinine excretion was 953 and 1,158 mg/day, respectively, with mixed glomerular and tubular proteinuria on urine electrophoresis. Serum IgA was elevated to 606 mg/dL, but other serologic tests for antinuclear antibody and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. C3 and C4 were 95 and 32 mg/dL, respectively.

Based on his travel history and clinical features, malaria was suspected, and a peripheral blood smear revealed 6% hyperparasitemia with Plasmodium falciparum. The patient was immediately prescribed intravenous quinine dihydrochloride with oral doxycycline on the second day of admission. However, he became anuric with increase in serum creatinine up to 4.7 mg/dL on the third day of admission, and was started on hemodialysis.

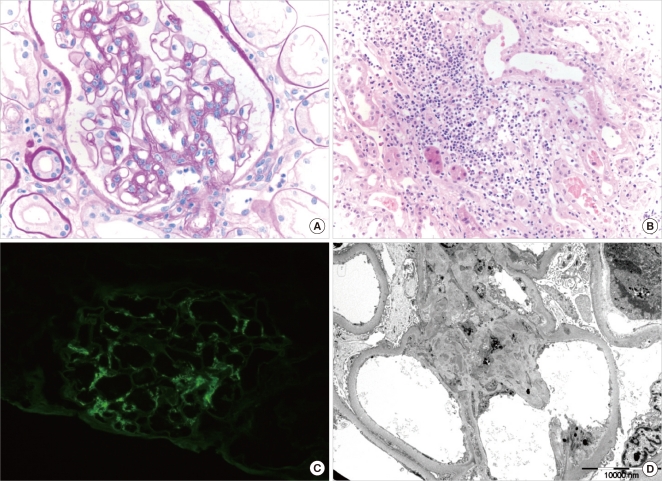

To further ascertain the cause of AKI and proteinuria, a kidney biopsy was performed on the 14th day after admission. On light microscopy, 11 glomeruli showed mild mesangial proliferation and expansion. In addition, some tubular lumens were packed with hemosiderin casts, and the interstitium was infiltrated with many inflammatory cells. Seven glomeruli processed for immunofluorescence analysis showed mesangial staining for IgA (1+ to 2+) and C3 (1+). In addition, 3 glomeruli examined by electron microscopy showed multifocal electron-dense deposits within the mesangium and thickened glomerular basement membrane ranging from 800 nm to 1,200 nm in thickness (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Pathologic findings in a patient with P. falcifarum-associated immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy. (A) The renal biopsy specimen showed mild mesangial proliferation and expansion (original magnification × 400). (B) Acute and chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in the tubulointerstitium with multifocal hemosiderin casts (original magnification × 200). (C) Direct immunofluorescence showed mesangial staining for IgA (2+). (D) Electron microscopy showed multifocal electron-dense deposits within the mesangium and irregularly thickened glomerular basement membrane ranging from 800 nm to 1,200 nm in thickness. Diffusely effaced foot processes were also observed.

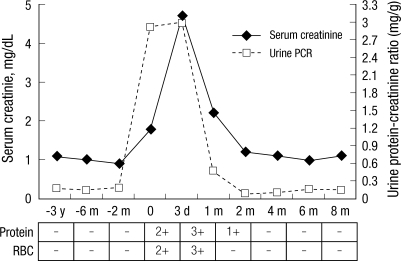

The patient underwent hemodialysis until the 25th day after admission. In the meantime, he became negative for P. falciparum and his kidney function recovered with increased urine output. Serum creatinine and UPCR decreased to 2.2 mg/dL and 0.47 mg/g on the 33rd day after admission, and the patient was discharged in good condition. Two months later, his serum creatinine level had decreased to 1.2 mg/dL with UPCR of 0.07 mg/g. Three consecutive urinalyses revealed no microhematuria (Fig. 2). Serum IgA was also normalized to 301 mg/dL.

Fig. 2.

Changes in kidney function and urine findings during the course of disease. d; day, m; month, y; year, PCR; protein-creatine ratio.

DISCUSSION

IgA nephropathy is the most common primary glomerulonephritis worldwide. It is characterized by mesangial cell proliferation, expansion of the extracellular matrix, and predominant IgA deposition within the mesangium (4). Although the etiology of the disease has not been clearly elucidated, some infectious organisms have been reported to be associated with IgA nephropathy. These include Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Staphylococcus species, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and the Hepatitis B and Dengue viruses, but no individual bacterial or viral organism has been specifically associated with the development of IgA nephropathy (5-9). Meanwhile, in an previous experimental study, mesangial IgA deposits were rarely noted in mouse malaria nephropathy caused by Plasmodium berghei (10). However, similar findings were not reported among human malaria nephropathy to date. To our best knowledge, this is the first case suggesting a possible link between IgA nephropathy and Plasmodium falciparum infection.

In line with the previous studies, AKI due to ATN and interstitial nephritis was clearly evident, which clearly explains our patient's clinical features. Notably, IgA nephropathy developed after Plasmodium falciparum infection. One might question whether the patient had glomerulonephritis or latent IgA nephropathy before the infection. However, the patient had been followed for 6 yr at our clinic for diabetes management, and previous blood and urine tests consistently had revealed no evidence of glomerulopathy. In addition, his urine analysis from 2 months before the illness showed no microscopic hematuria but only microalbuminuria suggesting that glomerulonephritis such as IgA nephropathy was less likely. Presumably, microalbuminuria at that time could have been attributed to underlying diabetic nephropathy. In fact, he might have diabetic nephropathy, as evidenced by the biopsy finding showing a thickened glomerular basement membrane and history of coexisting mild non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Moreover, subsequent blood and urine tests after recovery from malaria showed a disappearance of urine abnormalities along with normalization of both kidney function and serum IgA level. These findings taken together suggest that Plasmodium falciparum may have been associated with IgA nephropathy in this patient.

It is uncertain how malaria infection is involved in the development of IgA nephropathy. In general, undergalactosylated IgA1 is reported to play a role in the pathogenesis of idiopathic IgA nephropathy (11). Such aberrantly glycosylated polymeric IgA1 are prone to form circulating immune complexes, leading to mesangial deposition and proliferation (12, 13). The underlying mechanism responsible for this IgA1 abnormality is poorly understood. However, it is possible that anti-α-galactosyl (anti-Gal) antibodies may contribute to the development of immune complexes with aberrantly glycosylated IgA1. Anti-Gal antibodies are originally natural human polyclonal antibodies that specifically bind to the mammalian carbohydrate structure Galα1, 3Galβ1,4GlcNAc-R (α-galactosyl epitope) on glycoproteins and glycolipids (14). Some investigators showed that anti-Gal was associated with IgA nephropathy and Henoch-Schonlein purpura (15). Interestingly, the titers of these antibodies were also found to be elevated in many of the sera collected from subjects living in malaria endemic areas or patients with falciparum malaria (16). It was reported that terminal α-linked galactosyl residues in some of the carbohydrate side chains of glycoproteins of the asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum could provoke increased anti-Gal production (17, 18). Therefore, in the present case, it can be surmised that Plasmodium falciparum might have induced augmented production of anti-Gal, and in turn, might have caused formation of aberrantly glycosylated polymeric IgA1. Unfortunately, we could not perform any pertinent study to confirm the presence of abnormal IgA1 because the patient's serum was not available by the time the biopsy revealed IgA nephropathy.

Another possible explanation for IgA nephropathy in our report is that clearance of IgA and immune complexes were reduced due to liver and/or renal dysfunction. However, such assumptions cannot fully explain why IgA deposits were more prominent than other immune-complexes within the mesangium in our patient because only IgG, IgM, and C3 deposits have been reported in malarial nephropathies to date although most reported cases involved both renal failure and hepatitis.

As in some previous reports on IgA nephropathy associated with infection (9, 19), the glomerulopathy in our patient appeared to be transient. It is possible that removal of the causative organism from circulation and improvements in renal and hepatic dysfunction might result in increased clearance of immune-complexes, thus leading to the resolution of IgA nephropathy. Unfortunately, a second biopsy to prove the complete resolution of IgA nephropathy was not feasible because the patient did not agree to a repeated test. However, based on the results from consecutive blood and urine tests after recovery from malaria infection, it is likely that such glomerulopathy was resolved. In addition, although it is not easy to discriminate between true IgAN and IgA-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis, the latter was less likely because hypocomplementemia, diffuse glomerular endocapillary hypercellularity, and subepithelial humps (20) were not found in our case (Fig. 1).

In conclusion, our findings suggest that Plasmodium falciparum may be involved in the development of IgA nephropathy. However, this report is limited to a single case and the mechanism responsible for this remains speculative. Further investigation to elucidate the underlying pathogenesis is required.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World malaria report 2009. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barsoum RS. Malarial nephropathies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1588–1597. doi: 10.1093/ndt/13.6.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barsoum RS, Sitprija V. Tropical nephrology. In: Schrier RW, editor. Diseases of the kidney and urinary tract. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 2013–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donadio JV, Grande JP. IgA nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:738–748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunaga H, Oh M, Takahashi N, Fujieda S. Infection of Haemophilus parainfluenzae in tonsils is associated with IgA nephropathy. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2004:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satoskar AA, Nadasdy G, Plaza JA, Sedmak D, Shidham G, Hebert L, Nadasdy T. Staphylococcus infection-associated glomerulonephritis mimicking IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1179–1186. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01030306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki K, Hirano K, Onodera N, Takahashi T, Tanaka H. Acute IgA nephropathy associated with mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Pediatr Int. 2005;47:583–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang NS, Wu ZL, Zhang YE, Guo MY, Liao LT. Role of hepatitis B virus infection in pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2004–2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i9.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upadhaya BK, Sharma A, Khaira A, Dinda AK, Agarwal SK, Tiwari SC. Transient IgA nephropathy with acute kidney injury in a patient with dengue fever. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George CR, Parbtani A, Cameron JS. Mouse malaria nephropathy. J Pathol. 1976;120:235–249. doi: 10.1002/path.1711200407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barratt J, Feehally J, Smith AC. Pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2004;24:197–217. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coppo R, Amore A. Aberrant glycosylation in IgA nephropathy (IgAN) Kidney Int. 2004;65:1544–1547. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.05407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomana M, Novak J, Julian BA, Matousovic K, Konecny K, Mestecky J. Circulating immune complexes in IgA nephropathy consist of IgA1 with galactose-deficient hinge region and antiglycan antibodies. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:73–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI5535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamadeh RM, Galili U, Zhou P, Griffiss JM. Anti-alpha-galactosyl immunoglobulin A (IgA), IgG, and IgM in human secretions. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:125–131. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.2.125-131.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davin JC, Malaise M, Foidart J, Mahieu P. Anti-alpha-galactosyl antibodies and immune complexes in children with Henoch-Schönlein purpura or IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1987;31:1132–1139. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ravindran B, Satapathy AK, Das MK. Naturally-occurring anti-alpha-galactosyl antibodies in human Plasmodium falciparum infections: a possible role for autoantibodies in malaria. Immunol Lett. 1988;19:137–141. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(88)90133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramasamy R, Reese RT. Terminal galactose residues and the antigenicity of Plasmodium falciparum glycoproteins. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1986;19:91–101. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jakobsen PH, Theander TG, Jensen JB, Mølbak K, Jepsen S. Soluble Plasmodium falciparum antigens contain carbohydrate moieties important for immune reactivity. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:2075–2079. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.11.2075-2079.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han SH, Kang EW, Kie JH, Yoo TH, Choi KH, Han DS, Kang SW. Spontaneous remission of IgA nephropathy associated with resolution of hepatitis A. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:1163–1167. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasr SH, D'Agati VD. IgA-dominant postinfectious glomerulonephritis: a new twist on an old disease. Nephron Clin Pract. 2011;119:c18–c25. doi: 10.1159/000324180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]