Abstract

This paper describes the use of epoxy-encapsulated electrodes to integrate microchip-based electrophoresis with electrochemical detection. Devices with various electrode combinations can easily be developed. This includes a palladium decoupler with a downstream working electrode material of either gold, mercury/gold, platinum, glassy carbon, or a carbon fiber bundle. Additional device components such as the platinum wires for the electrophoresis separation and the counter electrode for detection can also be integrated into the epoxy base. The effect of the decoupler configuration was studied in terms of the separation performance, detector noise, and the ability to analyze samples of a high ionic strength. The ability of both glassy carbon and carbon fiber bundle electrodes to analyze a complex mixture was demonstrated. It was also shown that a PDMS-based valving microchip can be used along with the epoxy embedded electrodes to integrate microdialysis sampling with microchip electrophoresis and electrochemical detection, with the microdialysis tubing also being embedded in the epoxy substrate. This approach enables one to vary the detection electrode material as desired in a manner where the electrodes can be polished and modified in a similar fashion to electrochemical flow cells used in liquid chromatography.

1 Introduction

Advantages such as rapid analysis [1], the ability to manipulate small sample volumes [2], and the integration of multiple processes outside of the separation [3–6] have made the use of microchip systems for electrophoretic separations very popular. The use of electrochemistry to detect analytes after a microchip electrophoresis separation is an attractive alternative to the use of fluorescence detection. This is due to the inherent advantages of miniaturizing electrodes, the fact that many analytes (such as catecholamine neurotransmitters) can be detected directly without derivatization, and the selectivity that can be achieved with either judicious control over the detection potential or the use of multiple electrodes [7–11].

A challenge of integrating microchip electrophoresis with electrochemical detection is the need to minimize the interference between the separation field and the electrochemical detector. While there have been several approaches that include placing the electrodes in a reservoir [11, 12], it has been shown that a simple and reproducible method to perform this integration is through the use of a palladium “decoupler” electrode that is incorporated within the fluidic network to provide an electrophoretic ground and adsorb hydrogen produced from the reduction of water at the cathode [10, 13–16]. This approach enables a downstream working electrode to remain in the fluidic network, which helps to minimize band broadening processes that occur when electrodes are placed in a reservoir [12, 17, 18]. While there have been examples of manually placing metal wires into PDMS microchannels [15, 19, 20], the most popular approach of fabricating electrodes for microfluidics is through traditional sputtering and lithographic processing, followed by bonding of the electrode plate with a fluidic network [9, 14, 21–27]. Such patterned, thin-layer electrodes provide many advantages; however they are costly to produce and require a specialized facility for fabrication. With regard to microchip electrophoresis and use of a decoupler, it is also not trivial to integrate a detection electrode that differs from palladium. To do this with traditional fabrication techniques would require multiple sputtering/patterning steps with precise mask alignment. This has led our group to use carbon ink electrodes that are molded onto the electrode plate after the palladium decoupler has been patterned [3, 10, 23, 28]. Finally, thin-layer electrodes typically used for microchip applications are not able to be polished to generate a fresh electrode surface as is the case with both traditional electrode materials and electrochemical flow cells used for liquid chromatography. This limits the long-term re-usability of a device.

We recently described a new method of fabricating and integrating epoxy-embedded electrodes with microchip-based analysis systems [29]. This approach used a mold and commercially available epoxy to embed gold detection electrodes of various sizes. We demonstrated the applicability of these gold electrodes with microchip-based flow injection analysis and showed that the electrodes can be polished and modified in a similar fashion to electrochemical flow cells used in liquid chromatography. In this paper, we extend this approach to embedding multiple electrodes of differing composition for the purpose of integrating microchip electrophoresis with electrochemical detection. Devices with various electrode combinations can easily be developed. This includes a palladium decoupler with a downstream working electrode material of either gold (which can be modified with mercury to enable thiol detection), platinum, glassy carbon, or a carbon fiber bundle (which is widely used for neurotransmitter analysis). In addition, it is shown that this epoxy approach can be used to integrate additional device components, such as the platinum wires for the electrophoresis separation and the counter electrode for detection. The ability to embed fluidic tubing is also demonstrated with this approach and a valving-based microchip is used to integrate microdialysis sampling with microchip electrophoresis and electrochemical detection. Finally, the use of a carbon ink electrode array is shown to lead to significant signal enhancement.

2 Experimental

2.1 Chemicals and materials

The following chemicals and materials were used as received: Armstrong C-7 resin, Activator A, and Sylgard 184 (Ellsworth Adhesives, Germantown, WI, USA); Nano SU-8 developer, SU-8 50, SU-8 10 photoresist (Microchem, Newton, MA, USA); AZ 4620 positive resist and AZ 400 developer (AZ Resist, Somerville, NJ, USA); catechol, dopamine, epinephrine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid, boric acid, sodium dodecyl sulfate, potassium dicyanoaurate (I), sodium carbonate, liquid mercury, L-glutathione reduced, n-acetylcysteine, potassium chloride, sodium chloride, magnesium chloride, sodium phosphate, TES sodium salt, MES sodium salt, and HEPES (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA); 1 mm and 25 μm gold wire, 1 and 2 mm palladium wire, 1 mm glassy carbon, and 500 μm platinum wire (Alfa Aesar, Ward Hill, MA, USA); P-25 carbon fiber (Goodfellow Corporation, Oakdale, PA, USA); Ercon carbon ink and solvent thinner (Ercon, Wareham, MA, USA); soldering wire and heat shrink tubes (Radioshack); isopropanol and acetone (Fisher Scientific, Springfield, NJ, USA); colloidal silver (Ted Pella, Redding, CA, USA); BAS electrode polishing kit and microdialysis 4-mm brain probe (Bioanalytical Systems, West Lafayette, IN, USA); 8.89 cm diameter Teflon PTFE rod (McMaster-Carr, Chicago, IL, USA); HPFA tubing (360 μm o.d. and 150 μm i.d., IDEX Health and Science, Oak Harbor, WA, USA).

2.2 Fabrication and assembly

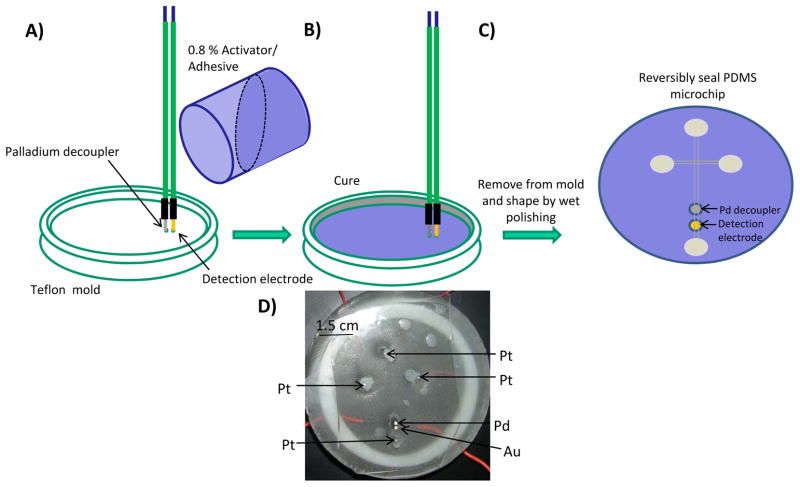

A brief summary of the epoxy-embedded electrode fabrication procedure is shown in Fig. 1. The two-part Teflon mold with an inner diameter of 7.87 cm was machined by traditional lathe-based turning. For all studies, two 1 mm electrode insertion holes were drilled with a 1 mm space in between. The first electrode insertion hole was used for the 1 mm Pd decoupler, and the second hole was used for the working electrode of desired material (gold, glassy carbon, carbon fiber bundle, or platinum). The desired electrode was affixed (soldered or connected with colloidal silver) to an extending copper wire to provide the electrical connection. The electrodes were inserted vertically into the insertion holes and a mixture of Armstong C-7 adhesive and 0.8% of Armstrong Activator A was poured into the mold (Fig 1A). The mixture was left to cure for at least two hours and then removed from the mold. Following the removal, the epoxy-embedded electrode base was shaped by wet polishing using a range (200–1200) of grits (Buehler, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) to achieve a fine polish. A BAS electrode polishing kit was used for everyday polishing prior to use. After polishing, the microchip was reversibly sealed over the epoxy-embedded electrodes before use (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Fabrication and assembly of epoxy-embedded electrodes: (A) A palladium decoupler and a detection electrode (gold, platinum, glassy carbon, carbon fiber bundle), affixed to connecting wires, are inserted (with a 1 mm spacing) into electrode insertion holes in a Teflon mold. (B) Armstrong C-7 resin is mixed with 0.8% Activator A and poured into the Teflon mold. The epoxy is left to cure for at least two hours, removed from the mold and shaped by wet polishing. (C) A PDMS microchip is reversibly sealed over the palladium and detection electrode. (D) Integration of palladium, gold, and platinum electrodes into an epoxy base with a PDMS microchip reversibly sealed over the palladium decoupler and gold detection electrode.

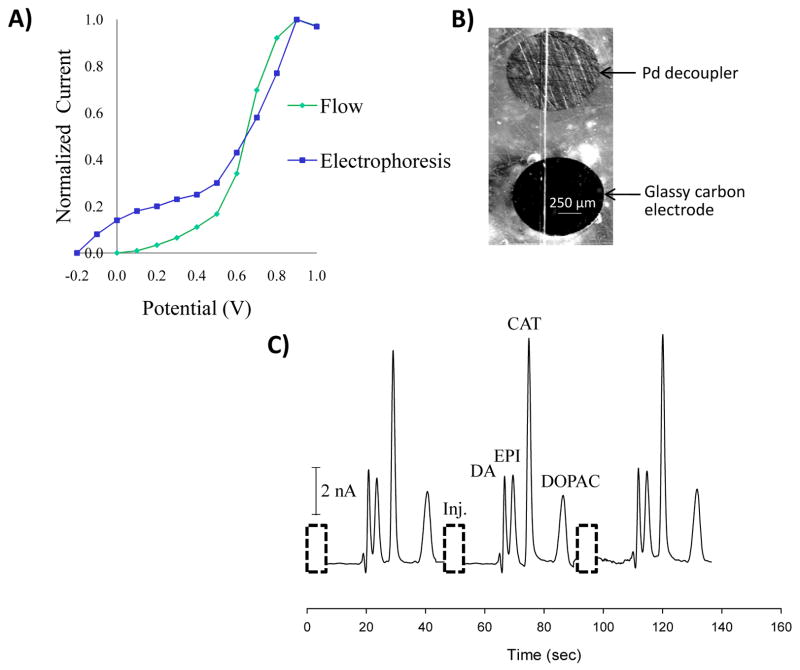

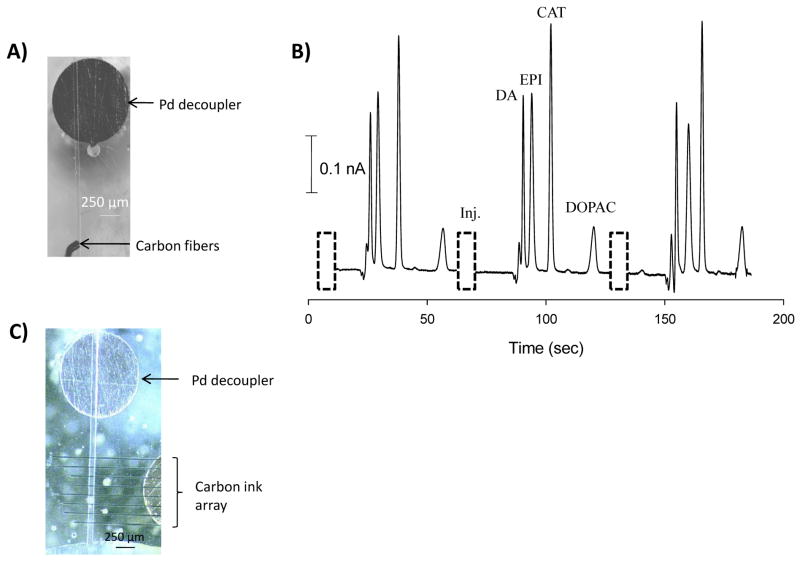

A variety of detection electrodes were used in these studies. Glassy carbon (Fig. 2B), a carbon fiber bundle (Fig. 3A) and platinum (Fig. 4B) electrodes could be used directly after polishing. As described in the Supporting Information, gold electrodes could be modified to form Hg/Au amalgam electrodes or pillar electrodes that protrude into the fluidic network (Figs. S-1 and S-2). A carbon ink microelectrode array could also be patterned on the surface of an embedded electrode (Fig. 3C) by using PDMS-based micromolding channels that were made from a double casting procedure [30]. Carbon ink microelectrodes were produced by sealing the rounded PDMS micromolding channels over a 1 mm gold electrode. The channels were filled with a carbon ink mixture and, after heating at 75 °C for 30 min, the mold was removed to leave the carbon ink electrodes patterned on the epoxy. The electrodes were further cured at 75 °C for 1.5 hrs before use.

Figure 2.

Use of a glassy carbon detection electrode. (A) Hydrodynamic voltammogram (HDV) comparing flow injection analysis and electrophoresis. (B) Micrograph of a 1 mm palladium decoupler and a 1 mm glassy carbon electrode. (C) Electropherogram for the separation and detection of dopamine (DA), epinephrine (EPI), catechol (CAT) (200 μM each), and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC, 750 μM).

Figure 3.

(A) Use of a carbon fiber microelectrode in microchip electrophoresis: Micrograph of a 1 mm palladium decoupler and a 100 μm carbon fiber bundle electrode. (B) Electropherogram for the separation and detection of dopamine (DA), epinephrine (EPI), catechol (CAT) (200 μM each), and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC, 750 μM) using a carbon fiber bundle detection electrode. (C) Micrograph of a 1 mm Pd decoupler and 8 carbon ink electrodes with a 1 mm gold electrode connector.

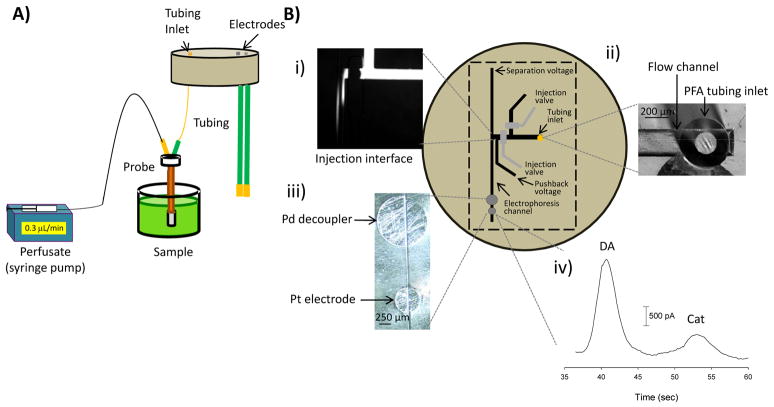

Figure 4.

Use of epoxy-embedded electrodes and tubing to enable the injection (via on-chip valves), electrophoretic separation and amperometric detection of dopamine and catechol sampled through a 4 mm microdialysis probe. (A) Schematic (side-view) that deptics the microdialysis set up and solution transfer through the epoxy base. (B) Top-down view of PDMS microchip sealed on epoxy base. (i) Micrograph of a pressure based injection, using on chip valves, into the electrophoresis channel; (ii) micrograph of a microfluidic flow channel reversibly sealed over epoxy-encapsulated PFA tubing; (iii) micrograph of a 1 mm decoupler and a 500 μm diameter Pt detection electrode; (iv) electropherogram for the separation and detection of dopamine (DA) and catechol (CAT).

2.3 Electrophoresis

Fabrication of the PDMS-based fluidic channels was based upon the use of soft lithography and silicon masters, as previously described, with SU-8 10 photoresist being used for the electrophoresis channels and SU-8 50 photoresist for PDMS-based flow injection channels [9, 10, 31]. The structure heights were measured using a profilometer (Dektak3 ST, Veeco Instruments, Woodbury, NY, USA). A 20:1 mixture of Sylgard 184 elastomer base and curing agent was poured onto the patterned silicon wafer and allowed to cure at 75 °C for 1 hr. After removal from the master, a hole punch was used to make reservoirs in the PDMS chips used for electrophoresis. For chips used for flow injections analysis, a 20-guage Luer stub adapter (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) was used to punch the inlet hole for the capillary [29]. The PDMS-based bilayer valving microchips that were used for microdialysis studies were fabricated using a negative resist for a valving layer master and a positive resist for a fluidic layer master [28, 32]. Following a partial cure step, the resulting PDMS structures were cured together to form a uniform, bilayer microchip. For all studies, PDMS structures were reversibly sealed over the electrode surface (as shown in Figs. 1C, D).

A LabSmith HVS448 3000 V High Voltage Sequencer with eight independent channels (LabSmith, Livermore, CA, USA) was used as the electrophoresis voltage source for all studies. The electrophoretic studies represented in Figs 2 and 3 used a gated injection scheme. The buffer consisted of 10 mM boric acid with 25 mM SDS (pH of 9.2). For these separations, injections were carried out by applying a high voltage (HV, +1000 V) to the buffer reservoir, a fraction of the HV (+800 V) to the sample reservoir, with the sample waste reservoir and decoupler being grounded (field strength = 200 V/cm). All separation channels were 2.75 cm long. A bilayer valving chip was used for the separation in Fig. 4B, with the separation channel being 24 μm tall and 40 μm wide. The operation of these valving chips has been described previously [28, 32]. In this study, a separation voltage of +700 V and a pushback voltage of +200 V were used (field strength = 144 V/cm). Amperometric detection was performed with gold, glassy carbon, carbon fiber, carbon ink, or platinum as the working electrode and a platinum wire served as the counter electrode.

The setup used for microchip-based flow injection analysis (used in Fig. 2A) was based on previous work [29, 31]. A PDMS flow channel (100 μm width, 100 μm height and 3 cm length) was reversibly sealed on the epoxy surface over the electrode. A buffer (10 mM MES, pH 5.5) was continuously pumped at 3.0 μL/min to the flow channel via a 500 μL syringe (SGE Analytical Science) and a syringe pump (Harvard 11 Plus, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). Injections (200 nL) of a 50 μM catechol sample were made via a 4-port injector (Vici Rotor, Valco Instruments, Houston, TX, USA). For the hydrodynamic voltammogram (HDV) comparison study, a Pt wire served as the auxiliary and Ag/AgCl was used as the reference electrode.

2.4 Microdialysis sampling

Perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) tubing was embedded into the epoxy base for microdialysis experiments. A 4-mm microdialysis brain probe was utilized. The PFA tubing was embedded into the epoxy base and the PDMS microchip was reversibly sealed over the tubing inlet (Fig. 4Bii). The brain probe was used to sample (at 0.3 μL/min) a solution of 200 μM dopamine and catechol. Discrete plugs were then injected into the separation channel by actuating the pneutmatic valves (Fig. 4Bi); following an electrophoretic separation the analytes were detected downstream at a 500 μm platinum detection electrode (Fig. 4Biii). A similar valving-based injection device with on-chip peristaltic pumps was used for the ionic strength comparison studies that are discussed in the results/discussion [3]. The cell stimulant buffer (pH 7.4) was made up of the following: 80 mM KCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.7 mM MgCl2, 1 mM NaH2PO4, and 10 mM HEPES [33]. The thin-layer palladium decoupler electrode used in the ionic strength comparison was fabricated by traditional sputtering and lithographic processing, as described previously [10, 14].

2.5 Imaging

Non-fluorescent images (Figs. 2–4) were captured from a stereoscope (Olympus SZ61) operating in bright-field mode using a Sony 3CCD color camera (Leeds Precision Instruments, Minneapolis, MN, USA). A fluorescent image (Fig. 4Bi) was taken using fluorescein (Sigma Aldrich) and an upright fluorescence microscope (Olympus EX 60) equipped with a 100 W Hg Arc lamp and a cooled 12-bit monochrome Qicam Fast digital CCD camera (Qimaging, Montreal, Canada). Images were captured with Streampix Digital Video Recording software (Norpix, Montereal, Canada) and Image Pro express software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) was used to measure channel dimensions and injection plug sizes.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Fabrication and initial characterization

We recently published a new approach (outlined in Fig. 1) to fabricate epoxy-embedded electrodes for microchip-based analysis systems that is simple, inexpensive, and reproducible [29]. In the initial study, gold detection electrodes were utilized with microchip-based flow analysis. We have expanded this approach here to integrate other materials of various composition and diameters such as 1 mm or 2 mm palladium, 1 mm glassy carbon, ~100 μm carbon fiber bundles, and 500 μm platinum electrodes. Importantly, as shown in Fig. 1, different materials can be incorporated in the same epoxy so that a palladium decoupler can be used with a variety of detection electrodes. As also seen in Fig. 1D, other electrodes such as the platinum wires for electrophoresis and a counter electrode can be embedded in the epoxy.

In our initial description of using thin-layer palladium decouplers (made from traditional sputtering and lithographic processing) to integrate microchip electrophoresis with electrochemical detection, it was noted that the distance between the decoupler leading edge and the detection electrode had an effect on the resulting electrophoretic separation [14]. This is due to increased band broadening from the parabolic flow profile that occurs after the decoupler. These epoxy-embedded electrodes were characterized for the optimal decoupler size. A 1 mm diameter palladium decoupler was compared to the use of a 2 mm diameter decoupler using the same detection electrode (1 mm gold), decoupler/electrode spacing (1 mm), and catechol (1 nL injection volume, n = 3 for each comparison) as a test analyte. It was found that use of the 2 mm decoupler reduced the peak-to-peak noise by a factor of ~2.4 (0.17 nA for the 1 mm decoupler and 0.07 nA for the 2 mm decoupler); however, the increased distance between the decoupler leading edge and the electrode led to a ~3.8 times decrease in the average peak height (1.1 nA for the 1 mm decoupler and 0.29 nA for the 2 mm decoupler) and a concurrent increase in peak width (2.39 s for the 1 mm decoupler and 6.22 s for the 2 mm decoupler). While the 2 mm decoupler was useful in decreasing noise, the increased band broadening that resulted from the increased distance between the decoupler leading edge and the detection electrode was deemed unfavorable for electrophoretic separations. It was also found that the 1 mm decoupler effectively dissipated hydrogen production up to field strengths of 800 V/cm for at least 30 mins, after which time the experiment was stopped (buffer = 25 mM boric acid with 1 mM SDS, pH 9.2). Higher field strengths led to bubble formation at the decoupler. For subsequent studies, the decoupler size was fixed to be 1 mm, with a 1 mm decoupler/electrode spacing.

Our first description of using epoxy-embedded electrodes mainly utilized microchip-based flow injection analysis to characterize the integration of gold detection electrodes into microfluidic channels [29]. Part of this work showed that a 1 mm gold wire could be easily amalgamated with mercury for selective thiol detection and a 25 μm gold wire could be used to create pillar electrodes (by an electrodeposition procedure) that protrude into the fluidic network [29]. It was found here that these types of detection electrodes can also be integrated with a palladium decoupler and used to monitor an electrophoretic separation. As detailed in the Supporting Information (Section S.1), a Hg/Au amalgam electrode that was 1 mm downstream from a palladium decoupler was used to separate and selectively detect a mixture of thiols (glutathione and n-acetylcysteine, see Fig S-1). In addition, as described in Section S.2 of the Supporting Information, a 12 μm tall and 40 μm wide pillar was integrated 1 mm away from a palladium decoupler (Fig. S-2). The performance of a flat 25 μm gold electrode was compared to the use this pillar electrode by injecting and separating a 50 μM catechol solution. The pillar resulted in a signal increase of 3.8 times greater than the flat electrode, demonstrating the ability of the pillar electrode to oxidize more analyte in a given area. This is similar to the improved signal that was seen in the previous flow injection work [29].

3.2 Integration of carbon electrodes

The preferred electrode for detecting catecholamine neurotransmitters is carbon. As compared to the use of metal electrodes, carbon electrodes have minimal fouling, a lower overpotential, and a larger potential range for organic compounds [11, 18]. Integrating carbon electrode materials with a palladium decoupler has primarily involved the use of carbon ink electrodes that are patterned over palladium connector electrodes [10, 30]. Traditional voltammetry and LC-flow cell experiments utilize glassy carbon (also known as vitreous carbon) as an electrode since it is a well-defined material that has low resistance and is compatible with most solvents [34]. As shown in Fig. 2, the ability to embed different materials with the epoxy encapsulation method enables the integration of a 1 mm glassy carbon detection electrode with a palladium decoupler. A HDV (see Fig. 2A) first showed that the optimal potential for both microchip-based flow injection analysis and microchip electrophoresis is +0.9 V. Since there is no observable shift in the voltammogram when microchip electrophoresis is performed, this demonstrates that the detection electrode is in a field free region [35, 36]. The glassy carbon electrode was next utilized for a separation of dopamine, epinephrine, catechol, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid using a 10 mM boric acid buffer containing 25 mM SDS (pH 9.2). A gated injection scheme was used to discretely inject 190 pL into the separation channel. The resolution was 1.2 between dopamine and epinephrine, 2.4 between epinephrine and catechol, and 3.3 between catechol and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid. The number of theoretical plates was 2,700 for catechol, which is typical for PDMS devices [37, 38].

While the glassy carbon detection electrode offers many advantages, the smallest commercially available glassy carbon electrode that we could obtain is 1 mm in diameter. In terms of the separation performance of electrophoresis, it is preferable to use smaller electrodes because a smaller detection window results in sharper, more resolved peaks. Carbon fiber electrodes have become very popular due to their small size and the ability to use these electrodes in vivo in conjunction with fast scan cyclic voltammetry [39]. In this study, a series of carbon fibers were bundled together to create a ~100 μm electrode that was placed 1 mm away from the palladium decoupler (Fig. 3A). The same gated injection scheme, field strength, and buffer as the glassy carbon separation were used for the injection (200 pL) and separation of dopamine, epinephrine, catechol, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (Fig. 3B). The resolution improved to 1.8 between dopamine and epinephrine, 3.7 between epinephrine and catechol, and 6.4 between catechol and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid. The number of theoretical plates increased to 6,300 for catechol, with this data showing a significant improvement in the separation performance due to the decreased electrode sensing area. For both the glassy carbon and carbon fiber studies, the final encapsulated material had a fixed alignment relative to the decoupler and the electrodes could be easily polished to a fresh surface before use, as is done with conventional LC flow cells. Since the PDMS was reversibly sealed over the carbon materials, a device could be disassembled, polished, and re-assembled daily between uses. While the carbon fiber resulted in efficient separations, the limit of detection (for catechol) was 2.6 μM (S/N = 3). A lower limit of detection is often desired for bioanalytical applications such as cellular analysis. Our group has previously reported that a carbon ink microelectrode array, with the electrodes held at the same potential, allows signal enhancement in microchip electrophoresis with electrochemical detection [30]. An optimally spaced array of electrodes (vs. a single electrode of the same electrode area) offers signal enhancement by allowing fresh analyte to diffuse to the surface of each electrode [21]. This same method can be used on the epoxy surface, with the carbon ink patterning having no effect on the epoxy base. As seen in Fig. 3C, 8 carbon ink electrodes were pulled over a 1 mm gold electrode, which was used for electrical connection. Use of a single carbon ink electrode resulted in a 2.0 μM limit of detection (LOD) for catechol, while the 8-electrode carbon ink array improved the limit of detection to 350 nM.

3.3 Integration of microdialysis sampling with microchip electrophoresis

Microdialysis is a popular continuous sampling method for in vivo systems [40, 41]. Since it is common to use low flow rates (<1 μL/min) to maximize recovery, low volume separation and detection techniques are required in order to decrease analysis time and minimize the amount of sample that must be collected. We have previously reported a microchip device that integrates microdialysis sampling, microchip electrophoresis, and electrochemical detection [28]. The fluidic interconnect for that device consisted of capillary tubing that was manually inserted into the top of the microchip through a punched hole. The dead volume and placement of the fluidic tubing can vary based upon how far the tubing is inserted into the microchip. In this work, we demonstrate the ability to embed PFA tubing within the epoxy base, along with a palladium decoupler and platinum detection electrode (Fig. 4). The epoxy could be polished as in other studies, with the dead volume of the tubing/chip interface remaining fixed. To demonstrate the applicability of this approach, a microdialysis brain probe with a 4-mm membrane was used to sample from a dopamine and catechol mixture. The perfusate and electrophoresis buffers were matched by using a 10 mM boric acid buffer with 25 mM SDS buffer (pH = 9.2). The analytes diffused across the membrane and were pumped (0.3 μL/min) onto the microchip through the epoxy-encapsulated tubing (Fig 4Bii). PDMS-based pneumatic valves were used to discretely inject 600 pL into the electrophoresis channel (Fig. 4Bi), with the separation resulting in a resolution of 1.65 between dopamine and catechol (Fig 4Biv).

A similar valving microchip was also used to investigate the effectiveness of the palladium decoupler when a high ionic strength buffer was used. Buffers needed for in vivo and in vitro studies have a very high salt content. In this study, we made use of a cell stimulant solution where the salt concentration was ~240 mM. It was found that a microfabricated thin-layer palladium decoupler was not as effective in dissipating the high electrophoretic currents (and resulting hydrogen production from the electrolysis of water) associated with these buffers. Use of a 2 mm (in length) thin-layer Pd decoupler (0.2 μm thickness) and repetitive injections (150 pL plug) of cell compatible buffer into the separation channel showed the highest field strength that could be used before bubble formation at the decoupler was 144 V/cm. A higher field strength was possible with the epoxy-embedded palladium decouplers (330 V/cm for a 1 mm diameter decoupler and 400 V/cm for a 2 mm decoupler) and these decouplers could effectively dissipate the hydrogen produced for at least ten injections (600 pL injection volume), after which the experiment was stopped. It is thought that the increased performance is due to the thickness of the Pd (~10 mm for the epoxy-based Pd and 0.2 μm for the thin-layer Pd) allowing more H2 dissipation. This should allow future in vitro and in vivo studies with this approach.

Conclusions

In this work, we have demonstrated the ability of epoxy-encapsulated electrodes to enable the integration of microchip electrophoresis and electrochemical detection in a manner where the detection electrode can be varied as desired. Established electrode materials such as carbon fiber and glassy carbon, which have not been commonly used in microchip-based systems, can be utilized and, in all cases, the epoxy-based electrodes can be polished before use. In addition, other microchip components such as electrophoresis electrodes, counter electrode, and fluidic tubing can be encapsulated. This work lays the foundation for future studies involving the investigation of other encapsulation materials and the use of the epoxy-embedded electrodes and an associated microchip to monitor the release of neurotransmitters from cultured cells [3, 42] as well as analyze the contents of droplets used to improve the temporal resolution for microdialysis sampling [43].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project described was supported by Award Number R15GM084470-03 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Jacobson SC, Culbertson CT, Daler JE, Ramsey JM. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3476–3480. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li MW, Bowen AL, Batz NG, Martin RS. In: Lab on a Chip Technology, Part II: Fluid Control and Manipulation. Herold KE, Rasooly A, editors. Caister Academic Press; Nofolk, UK: 2009. pp. 385–403. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowen AL, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:2534–2540. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noblitt SD, Lewis GS, Liu Y, Hering SV, Collett JL, Henry CS. Anal Chem. 2009;81:10029–10037. doi: 10.1021/ac901903m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Easley CJ, Karlinsey JM, Bienvenue JM, Legendre LA, Roper MG, Feldman SH, Hughes MA, Hewlett EL, Merkel TJ, Ferrance JP, Landers JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19272–19277. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604663103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li MW, Martin RS. Analyst. 2008;133:1358–1366. doi: 10.1039/b807093h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wightman RM. Anal Chem. 1981;53:1125A–1134A. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gawron AJ, Martin RS, Lunte SM. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:242–248. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200101)22:2<242::AID-ELPS242>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin RS, Gawron AJ, Lunte SM, Henry CS. Anal Chem. 2000;72:3196–3202. doi: 10.1021/ac000160t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mecker LC, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2006;27:5032–5042. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandaveer WR, Pasas-Farmer SA, Fischer DJ, Frankenfeld CN, Lunte SM. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:3528–3549. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasas SA, Fogarty BA, Huynh BH, Lacher NA, Carlson B, Martin RS, Vandeveer WR, IV, Lunte SM. In: Separation Methods in Microanalytical Systems. Kutter JP, Fintschenko Y, editors. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovarik ML, Li MW, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:202–210. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacher NA, Lunte SM, Martin RS. Anal Chem. 2004;76:2482–2491. doi: 10.1021/ac030327t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vickers JA, Henry CS. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:4641–4647. doi: 10.1002/elps.200500508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen DC, Hsu FL, Zhan DZ, Chen CH. Anal Chem. 2001;73:758–762. doi: 10.1021/ac000452u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin RS. Methods in Molecular Biology. In: Henry CS, editor. Microchip Capillary Electrophoresis: Methods and Protocols. Vol. 339. Humana Press; Towtowa, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandaveer WR, Pasas SA, Martin RS, Lunte SM. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:3667–3677. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200211)23:21<3667::AID-ELPS3667>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holcomb RE, Kraly JR, Henry CS. Analyst. 2009;134:486–492. doi: 10.1039/b816289a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Vickers JA, Henry CS. Anal Chem. 2004;76:1513–1517. doi: 10.1021/ac0350357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amatore C, Da Mota N, Lemmer C, Pebay C, Sella C, Thouin L. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9483–9490. doi: 10.1021/ac801605v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batz NG, Martin RS. Analyst. 2009;34:372–379. doi: 10.1039/b813898b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen AL, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2009;30:3347–3354. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keynton RS, Roussel TJ, Crain MM, Jackson DJ, Franco DB, Naber JF, Walsh KM, Baldwin RP. Anal Chim Acta. 2004;507:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manica DP, Mitsumori Y, Ewing AG. Anal Chem. 2003;75:4572–4577. doi: 10.1021/ac034235f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pai RS, Walsh KM, Crain MM, Roussel TJ, Jackson DJ, Baldwin RP, Keynton RS, Naber JF. Anal Chem. 2009;81:4762–4769. doi: 10.1021/ac9002529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woolley AT, Lao K, Glazer AN, Mathies RA. Anal Chem. 1998;70:684–688. doi: 10.1021/ac971135z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mecker LC, Martin RS. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9257–9264. doi: 10.1021/ac801614r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selimovic A, Johnson AS, Kiss IZ, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2011;32:822–831. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mecker LC, Filla LM, Martin RS. Electroanalysis. 2010;22:2141–2146. doi: 10.1002/elan.201000118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kovarik ML, Torrence NJ, Spence DM, Martin RS. Analyst. 2004;129:400–405. doi: 10.1039/b401380h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li MW, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2007;28:2478–2488. doi: 10.1002/elps.200600713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozminski KD, Gutman DA, Davila V, Sulzer D, Ewing AG. Anal Chem. 1998;70:3123–3130. doi: 10.1021/ac980129f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCreery RL, Cline KK. In: Laboratory Techniques in Electroanalytical Chemistry. Kissinger PT, Heineman WR, editors. Marcel Dekker, Inc; New York: 1996. pp. 293–332. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin RS, Ratzlaff KL, Huynh BH, Lunte SM. Anal Chem. 2002;74:1136–1143. doi: 10.1021/ac011087p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wallenborg SR, Nyholm L, Lunte CE. Anal Chem. 1998;71:544–549. doi: 10.1021/ac980737v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vickers JA, Caulum MM, Henry CS. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7446–7452. doi: 10.1021/ac0609632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lacher NA, de Rooij NF, Verpoorte E, Lunte SM. J Chromatogr A. 2003;1004:225–235. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00722-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heien MLAV, Johnson MA, Wightman RM. Anal Chem. 2004;76:5697–5704. doi: 10.1021/ac0491509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davies MI, Cooper JD, Desmond SS, Lunte CE, Lunte SM. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2000;45:169–188. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00114-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shou M, Ferrario CR, Schultz KN, Robinson TE, Kennedy RT. Anal Chem. 2006;78:6717–6725. doi: 10.1021/ac0608218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hulvey MK, Martin RS. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;393:599–605. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2468-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Filla LA, Kirkpatrick DC, Martin RS. Anal Chem. 2011;83:5996–6003. doi: 10.1021/ac201007s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.