Abstract

The Bcl-2 regulated apoptosis pathway is critical for the elimination of autoreactive lymphocytes, thereby precluding autoimmunity. T cells escaping this process can be kept in check by regulatory T (Treg) cells expressing the transcription and lineage commitment factor Foxp3. Despite the well-established role of Bcl-2 family proteins in shaping the immune system and their frequent deregulation in autoimmune pathologies, it is poorly understood how these proteins affect Treg cell development and function. Here we compared the relative expression of a panel of 40 apoptosis-associated genes in Treg vs. conventional CD4+ T cells. Physiological significance of key-changes was validated using gene-modified mice lacking or overexpressing pro- or anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members. We define a key role for the Bim/Bcl-2 axis in Treg cell development, homeostasis and function but exclude a role for apoptosis induction in responder T cells as relevant suppression mechanism. Notably, only lack of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein Bim or Bcl-2 overexpression led to accumulation of Treg cells while loss of pro-apoptotic Bad, Bmf, Puma or Noxa had no effect. Remarkably, apoptosis resistant Treg cells showed reduced suppressive capacity in a model of T cell-driven colitis, posing a caveat for the use of such long-lived cells in possible therapeutic settings.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Regulatory T cells, Bim, Bcl-2, Autoimmunity

Abbreviations: TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TCR, T cell receptor; Bcl-2, B cell lymphoma 2; Bim/Bcl-2L1, 1Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; Tcon, conventional CD4+ T cells; iTreg, induced regulatory T cells; nTreg, natural regulatory T cells; Foxp3, Forkhead box P3; GFP, green fluorescent protein; IL, interleukin; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; BH, Bcl-2 homology; GITR, glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4

Highlights

► nTreg cells differ in their cell death responsiveness from conventional T cells. ► Cell death defects cause reduced expression of Treg cell markers. ► Treg cells defective in apoptosis induction show impaired suppressive capacity. ► Cell death defective Treg cells fail to effectively suppress inflammatory bowel disease.

1. Introduction

Regulatory T (Treg) cell dependent suppression and apoptosis of immune effector cells are both essential in establishing and maintaining peripheral tolerance. Failure in either process can result in an overshooting immune response and foster the development of autoimmunity.

Two separate apoptosis signalling pathways contribute to preclude autoimmunity. The extrinsic pathway is induced by ligation of membrane-bound death receptors (DR; e.g. CD95 or TRAIL-R) with their cognate ligands (CD95L or TRAIL), whereas the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway is triggered in response to diverse forms of cell stress including cytokine-deprivation or high-affinity ligation of antigen receptors and mediated by proteins of the Bcl-2 family [1]. The latter are divided according to function in anti- and pro-apoptotic proteins. Anti-apoptotic proteins (e.g. Bcl-2, Bcl-x or Mcl-1) contain up to four Bcl-2-homology domains (BH1-4), pro-apoptotic Bax/Bak-like proteins three (BH1-3) and ‘BH3-only’ proteins (e.g. Bim, Puma) only one, i.e. the BH3 domain.

Defective signalling along the extrinsic apoptosis pathway can underlie the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease in mice and humans as exemplified by the loss of CD95-mediated apoptosis in autoimmune prone lpr mice and patients suffering from autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) [2]. Also, deviations of the intrinsic pathway contribute to the establishment of autoimmunity. Loss of Bim or Bcl-2 overexpression in mice impairs negative selection of thymocytes and developing B cells expressing self-reactive antigen receptors and Bim plus Puma co-regulate lymphocyte homeostasis in the periphery [3]. Forced overexpression of Bcl-2 or Mcl-1 causes lymphadenopathy, can facilitate cancer development [4,5] and the former also facilitates autoimmunity in mice [6,7]. Deletion of activated cells after antigenic challenge is impaired in Bim-deficient or Bcl-2 overexpressing animals thereby facilitating the development of SLE-like pathology [7,8]. Consistently, high-level expression of Bcl-2 or its pro-survival homologues is frequently associated with different types of AID in humans [9–11].

Treg cells are characterized by the expression of distinct cell surface molecules including CD4, the IL-2Rα chain (CD25), GITR and CTLA-4 but the transcription factor Foxp3 appears to be the only reliable marker [12]. Treg cells arise naturally in the thymus (nTreg) or can be induced (iTreg) in the periphery from CD4+Foxp3− naïve T cells in response to TGF-β plus IL-2 or retinoic acid [13]. Their immune suppressive capacity involves the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. TGF-β, IL-10), cell-to-cell contact dependent mechanisms (e.g. CTLA-4) or active transfer of small immune-modulatory metabolites such as cAMP [14,15]. Previous reports also suggested that induction of apoptosis in activated T cells, e.g. due to expression of DR ligands such as TRAIL [16] or CD95L [17] on Treg cells, or Treg-dependent IL-2 deprivation of activated T cells [18], triggering Bcl-2 regulated cell death, may contribute.

Loss of Foxp3 triggers the scurfy phenotype in mice and immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked inheritance (IPEX) in humans [19,20]. Importantly, the timed deletion of Treg cells in adult mice results in scurfy-like pathology [21]. Moreover, Treg number and function are frequently reduced in patients suffering from autoimmunity [22,23]. These findings demonstrate the importance and simultaneously highlighting the therapeutic potential of Treg cells for the treatment of autoimmunity or other pathologies such as graft vs. host disease.

Despite the well-established role of Bcl-2 family proteins in lymphocyte development and homeostasis, only fragmented information is available concerning their impact on Treg cell biology. To gain insight, we investigated the relative expression levels of Bcl-2 family proteins in Treg cells derived from thymus or spleen in relation to that found in developing thymocytes or conventional CD4+ T cells. In addition, we explored the impact of loss- or gain-of-function of key Bcl-2 family proteins on Treg cell development, their cell death responsiveness as well as their suppressor function in vitro and in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

C57BL/6 foxp3gfp reporter mice [24] were purchased from Jackson Laboratories, backcrossed 3 more generations to C57BL/6 (total 8 times) and crossed with congenic Bim−/− [8], vav-Bcl-2 [25] mice to obtain foxp3gfpBim−/− and foxp3gfpvav-Bcl-2 mice. RAG1−/− mice were a kind gift from A. Moschen, Department of Internal Medicine II. The generation of mice deficient for Bad [26], Bmf [27], Puma [28] or Noxa [28] has been described. All animals used in this study were on a C57BL/6 background and 6–12 weeks of age. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Austrian “Tierversuchsgesetz” (BGBl. Nr. 501/1988 i.d.F. 162/2005) and have been granted by the Bundesministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur (BMWF-66.011/0167-II/3b/2011).

2.2. Cell sorting

To obtain CD4+Foxp3-GFP− conventional T cells and CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ natural Treg cells single cell suspensions were prepared from splenocytes and thymocytes isolated from foxp3gfp wild type, foxp3gfpBim−/−, foxp3gfpvav-Bcl-2 mice and stained with fluorochrome-labelled antibodies recognizing mouse CD4 and 7AAD to exclude dead cells. Cell sorting was performed using a FACSVantage cell sorter (Becton Dickinson). Purity of isolated cell populations was routinely ≥98%.

2.3. Flow cytometry

The following fluorochrome-labelled antibodies or reagents were used for extra- and intracellular staining: rat anti-mouse CD4 mAb (L3T4), rabbit anti-mouse GITR (YGITR 765, Biolegend), rat anti-mouse Foxp3 (FJK-16s) from eBioscience; 7AAD from Sigma–Aldrich; rat anti-mouse CD25 mAb (3C7), hamster anti-mouse CTLA-4 mAb (UC10-4B9) and AnnexinV-Alexa647, rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (XMG1.2), rat anti-mouse IL-17A mAb (TC11-18H10.1) from Biolegend.

For intracellular staining of cytokines cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PMA (Fluka Biochemika) and 1 μg/ml Ionomycin (Sigma) for 5 h. During the last 3 h of cell culture Monensin (Biolegend) was added. Then cells were fixed with fixation buffer and permeabilized with permeabilization buffer (Biolegend) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For intracellular Foxp3 staining, buffers were purchased from eBioscience. Flow cytometry measurements were performed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by Cellquest™ (BD Biosciences) or WinMDI.

2.4. Apoptosis assays

To asses apoptosis susceptibility cells were cultured in media (supplemented with 10% FCS, 100 U/ml Pen/Strep, 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM pyruvate, 1× non-essential amino acids, 50 μM beta-mercaptoethanol) in the presence or absence of 100 U/ml IL-2 (Peprotech), 20 ng/ml IL-7 (Peprotech), 10−8 M Dexamethasone (Sigma–Aldrich), 10 μg/ml Etoposide (Sigma–Aldrich), 1 μM SAHA (a gift from R. Johnstone, Peter MacCallum Cancer Center, Melbourne, Australia), 100 nM Staurosporine (Sigma–Aldrich). To induce apoptosis by Fas ligation, cells were cultured in the presence of human 100 ng/ml FasL (Alexis Biochemicals) and crosslinked with 1 μg/ml anti-FLAG (M2, Sigma–Aldrich). The percentage of living cells was assessed by AnnexinV/7AAD staining. Increased and relative survival was calculated by normalisation to medium cultured cells.

2.5. T cell suppression assay

Freshly purified CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ nTreg cells were tested functionally in a co-culture suppression assay. Triplicates of different nTreg cell ratios were co-cultured with 5 × 104/ml splenic CD4+Foxp3-GFP− responder T cells, 2 × 105/ml APCs (irradiated total splenocytes, 30 Gy) and 0.5 μg/ml anti-CD3 (2C11) in 96-well U-bottom plates for 72 h. 1 μCi [3H]-thymidine/well was added for the last 16 h. Cells were transferred onto glass fiber filters using a Combi-cell-harvester (Molecular Devices) and proliferation measured by scintillation counting in a beta-Counter (Beckman Coulter).

2.6. RNA isolation and quantitative RT-PCR

RNA isolation (Zymo research) and cDNA synthesis (Biorad) were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real time PCR was done using the following primers (5′–3′): A1 CCTGGCTGAGCACTACCTTC (sense) and TCCACGTGAAAGTCATCCAA (antisense); β-actin ACTGGGACGACATGGAGAAG (sense) and GGGGTGTTGAAGGTCTCAAA (antisense); Bcl-2, CTGGCATCTTCTCCTTCCAG (sense) and GACGGTAGCGACGAGAGAAG (antisense); Bcl-xL TTCGGGATGGAGTAAACTGG (sense) and TGGATCCAAGGCTCTAGGTG (antisense); Bim GAGATACGGATTGCACAGGA (sense) and TCAGCCTCGCGGTAATCATT (antisense); Mcl-1 TAACAAACTGGGGCAGGATT (sense) and GTCCCGTTTCGTCCTTACAA (antisense); Noxa CCCACTCCTGGGAAAGTACA (sense) and AATCCCTTCAGCCCTTGATT (antisense); Puma CAAGAAGAGCAGCATCGACA (sense) and TAGTTGGGCTCCATTTCTGG (antisense). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using a Mastercycler® Gradient (Eppendorf) and the DyNAmo™ Flash SYBR mastermix (Finnzymes) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The results were normalized to β-actin expression and evaluated using the −ΔΔCT relative quantification method.

2.7. Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (RT-MLPA)

RNA amounts were analyzed with the Apoptosis Mouse RT-MLPA kit RM002 (MRC-Holland, http://www.mlpa.com) according to the manufacturer’s instructions [29]. Samples were run through a Genescan and analyzed with Gene-Mapper (Applied Biosystems GmbH; http://www.appliedbiosystems.com) and subsequently using the Statview© software program (Abacus).

2.8. T cell transfer model of colitis

CD4+Foxp3-GFP− conventional T cells were isolated from congenic C57BL/6 foxp3gfp mice and injected i.p. into 6–10-week-old C57BL/6 RAG1−/− immunodeficient recipients (4 × 105 cells/mouse). 1 × 105 wild type or vav-Bcl-2 CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells were co-injected i.p. where indicated. Mice were monitored every 3–4 days for wasting disease. Mice were sacrificed either losing >25% of its initial body weight or 7 weeks after cell transfer.

2.9. Histological assessment of intestinal inflammation

Samples of proximal colon, mid-colon, and distal colon were fixed in buffered 4% formalin solution. 3 μm paraffin-embedded sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Tissues were graded semi-quantitatively from grade 0 to 4 in a blinded fashion. Grade 0: no changes observed, grade 1: discrete increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria with granulocytes in the lamina epithelialis, grade 2: as grade 1 with scattered erosions of the mucosa, grade 3: increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria and scattered crypt abscesses, grade 4: all signs of grade 3 plus more than 3 crypt abscesses per colon circumference in the scanning magnification (40×).

2.10. Statistics

Estimation of statistical differences between groups was carried out using the unpaired Student’s t-test or Mann Whitney U test, where appropriate. P-values of ≤ 0.05 were considered to indicate statistically significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. Distinct expression patterns of anti- and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members are found in nTreg vs. conventional T cells

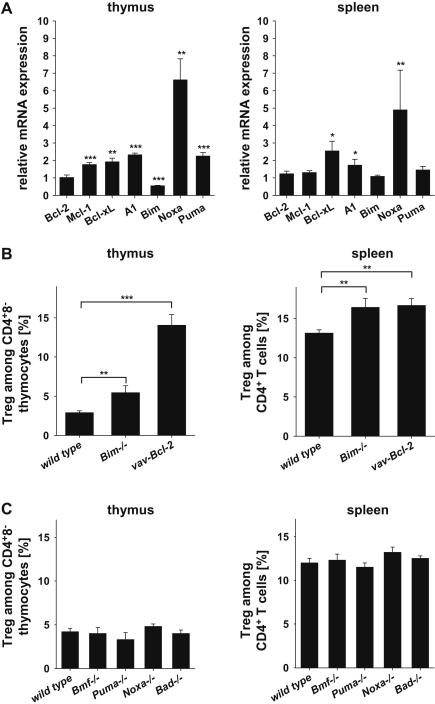

First we investigated if Treg and conventional CD4+ T cells (Tcon) differ in their repertoire of 40 apoptosis-associated genes, including all pro- and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members. Therefore, Treg cells, CD4+8− thymocytes or CD4+ Tcon cells were isolated from the thymus or spleen of foxp3gfp reporter mice based on cell surface marker and GFP expression by cell sorting. RNA was isolated and analyzed by RT-MLPA (Suppl. Table 1) and quantitative (q)RT-PCR (Fig. 1A). In the thymus, Treg cells expressed higher mRNA levels encoding anti-apoptotic Mcl-1, Bcl-xL or A1/Bfl-1, when compared to CD4+8− thymocytes. In contrast, expression of pro-apoptotic Bim was found reduced in Treg cells while mRNA for Puma was more and that for Noxa seemed most abundant in this relative comparison (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Differential expression of proteins of the Bcl-2 family by Treg cells in the thymus and spleen. CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg, CD4+8−Foxp3-GFP− thymocytes, or CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells were isolated from the (A) thymus or spleen, respectively. Relative mRNA expression of Bcl-2 family members was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. Expression in CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells was set to 1. Bars represent means ± SEM of n = 5 independent samples. (B) Relative abundance of CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells among CD4+ T cells in the thymi and spleens of foxp3gfpwt (n = 8), foxp3gfpBim−/− (n = 3) and foxp3gfpvav-Bcl-2 (n = 5) mice. (C) Abundance of CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells among CD4+ T cells in the thymi and spleens of wt (n ≥ 8), Bmf−/− (n ≥ 4), Puma−/− (n ≥ 5), Noxa−/− (n = 2) and Bad−/− (n = 2) mice. Bars represent means ± SEM; statistics: Student’s t-test and Mann Whitney U test for Noxa in the spleen. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

In contrast, in the spleen only mRNAs for Bcl-xL, A1/Bfl-1 and Noxa were found to be overrepresented in Treg cells, whereas no difference was observed for transcripts encoding Bcl-2, Mcl-1, Bim or Puma, suggesting that Bcl-xL levels may define increased cell death thresholds in nTreg cells in the periphery. All other cell death related genes amplified in the RT-MLPA analysis were either not expressed or found comparable in their levels with one notable exception, BIRC1A/NAIP, a member of the NOD-like receptor family, initially implicated as an apoptosis inhibitor in neurons, that was significantly more abundant in Treg cells derived from thymus or spleen (Suppl. Table 1).

Next we investigated if loss of BH3-only protein function or Bcl-2 overexpression had an impact on nTreg cell homeostasis in vivo. Therefore, we quantified the percentage and number of CD4+Foxp3+Treg cells in the thymus and spleens of mice lacking the BH3-only proteins Bim, Bmf, Bad, Puma or Noxa and compared it to the consequences of transgenic overexpression of Bcl-2. This analysis revealed a relative increase in the percentage of nTreg cells in Bim-deficient or vav-Bcl-2 transgenic mice (Fig. 1B). No differences in Treg cell number were observed in all other knockout animals analyzed (Fig. 1C), including those lacking Puma or Noxa, despite the higher mRNA levels observed in wild type Treg cells (Fig. 1A).

3.2. nTreg cells differ in their cell death responsiveness from conventional T cells

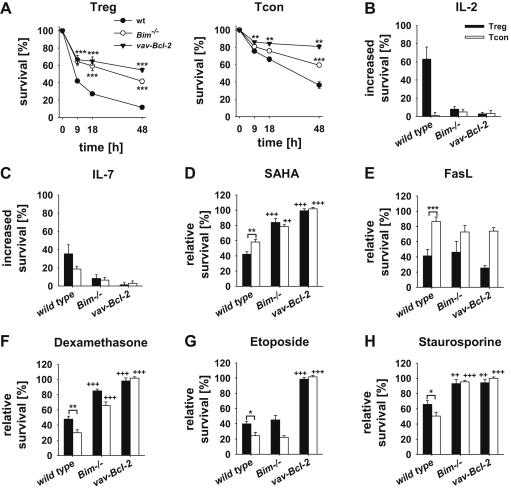

Based on our findings related to gene expression and the observed accumulation of Treg cells in Bim-deficient or Bcl-2 overexpressing mice, we assessed if Treg cells differ from CD4+8− thymocytes or CD4+ Tcon cells from spleen in their susceptibility to apoptosis. Therefore, CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells, CD4+8−Foxp3-GFP− thymocytes or CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells were isolated from the thymus or spleen of mice from the different genotypes. Cells were exposed to a broad range of apoptotic stimuli triggering Bcl-2 dependent apoptosis, including cytokine deprivation, treatment with the glucocorticoid dexamethasone, the DNA-damaging drug etoposide, the histone-deacetylase (HDAC)-inhibitor SAHA, the broad-spectrum kinase-inhibitor staurosporine and, for reference, CD95 ligation. Compared to CD4+8− thymocytes (Suppl. Fig. 1) or splenic Tcon cells (Fig. 2), Treg cells died more rapidly in the absence of cytokines and were efficiently rescued by addition of IL-2, in line with their strict dependence on this cytokine for survival [30], but also by the addition of IL-7. Consistently, loss of Bim as well as Bcl-2 overexpression protected them from spontaneous death in culture (Fig. 2A–C). Next to cytokine deprivation, Treg cells were found more susceptible to apoptosis induced by the HDAC inhibitor SAHA, and Fas ligation (Fig. 2D, E). Loss of Bim or Bcl-2 overexpression protected Treg cells from SAHA but not CD95-induced apoptosis. In contrast, Treg cells were more resistant to apoptosis induced by the glucocorticoid dexamethasone, etoposide or staurosporine when compared with Tcon cells (Fig. 2F–H). This difference might be explained with increased level of Bcl-xL in these cells (Fig. 1), whereas in the thymus, Treg cells displayed increased survival only in response to staurosporine treatment. As in Tcon cells, absence of Bim or Bcl-2 overexpression conferred partial or complete protection to dexamethasone or staurosporine while etoposide killing was only blocked by Bcl-2 overexpression (Fig. 2; Suppl. Fig. 1).

Fig. 2.

Splenic Treg and Tcon cells display different susceptibility to mitochondrial apoptosis. Wild type, Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg and CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells were purified from the spleen and survival analyzed by AnnexinV/7AAD staining. Only AnnexinV/7AAD negative cells were considered alive. Cells were cultured either (A) in medium for 9, 18 and 48 h or in the presence of (B) 100 U/ml IL-2, (C) 20 ng/ml IL-7, (D) 1 μM SAHA, (E) 100 ng/ml FasL, (F) 10−8 M Dexamethasone, (G) 10 μg/ml Etoposide and (H) 100 nM Staurosporine for 18 h. For calculation of increased and relative survival cell viability was normalized to medium values. Symbols and bars represent means ± SEM of n = 3–10 data points acquired in ≥3 independent experiments; statistics: Student’s t-test *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001 Treg cells were compared to Tcon cells; ++p ≤ 0.01, +++p ≤ 0.001 wild type Treg and Tcon cells, respectively were compared to their Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 counterparts.

Collectively, our findings show that although cell death signalling pathways and responses are generally conserved between Tcon and Treg cells, differences in relative sensitivity to certain forms of stress do exist, that correlate with the different expression patterns of certain Bcl-2 family proteins described above (Fig. 1).

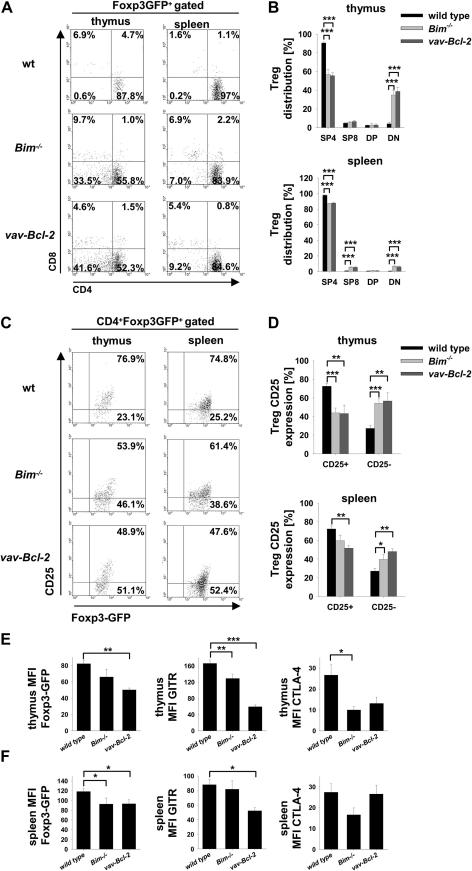

3.3. Reduced expression of Treg cell markers due to loss of Bim or Bcl-2 overexpression

Because apoptosis differently affected Treg and Tcon cells we wanted to know if and how deregulation of cell death impacts on Treg cell phenotype and function. Therefore, we analyzed expression of Treg cell markers in foxp3gfpwild type, foxp3gfpBim−/− and foxp3gfpvav-Bcl-2 mice, the latter two showing increased Treg cell numbers. While in wild type mice nearly all Foxp3-GFP+ cells were CD4+ (Fig. 3A, B), we observed an increased number of CD8+Foxp3-GFP+ cells in the spleens of foxp3gfpBim−/− and foxp3gfpvav-Bcl-2 mice. Surprisingly, up to 40% of Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Foxp3-GFP+ cells in the thymus lacked CD4 or CD8 expression and even migrated to the periphery (Fig. 3A, B). Furthermore, expression of typical Treg cell markers, such as Foxp3, CD25 and GITR were diminished in Bim−/− mice, an effect even more pronounced, in vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells (Fig. 3C–F and Suppl. Fig. 2). CTLA-4 expression, required for Treg cell effector function, was significantly reduced in thymic Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells but this phenomenon was no longer seen in the spleen. Overall, Treg cell marker reduction was more pronounced in the thymus than the spleen. Together this indicates, that defective cell death signalling impacts on the maturation program of Treg cells that may also impact on their effector function.

Fig. 3.

Treg cell marker expression is reduced in Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells. (A) Representative dot-plot analysis of CD4 and CD8 cell surface marker expression by Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells in the thymus (left column) or spleen (right column) of wild type, Bim−/− or vav-Bcl-2 mice. (B) Quantification of CD4 and CD8 distribution among of Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells in the thymus (upper panel) or spleen (lower panel). Bars represent means ± SEM of wt n = 11; Bim−/−n = 6; vav-Bcl-2 n = 5 animals. (C) Representative dot-plot analysis of CD25 expression on the cell surface of wild type, Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells in the thymus (left column) or spleen (right column). (D) Quantification of CD25 expression as in (B). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Foxp3-GFP, GITR and CTLA-4 by CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells in the (E) thymus or (F) spleen (wt n ≥ 9; Bim−/−n ≥ 3; vav-Bcl-2 n ≥ 3); bars represent means ± SEM of ≥3 independent experiments; statistics: Student’s t-test *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

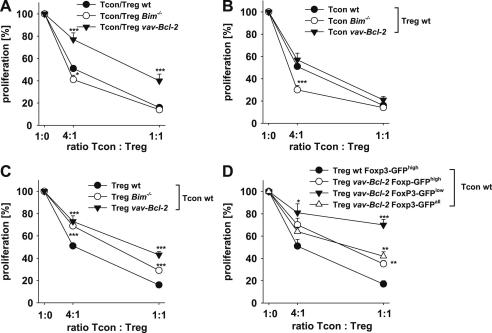

3.4. Treg cells derived from foxp3gfpBim−/− or foxp3gfpvav-Bcl-2 mice show impaired suppressive capacity

Expression levels of Foxp3 in Treg cells highly correlate with their suppressive capacity and forced expression of Foxp3 in former Foxp3−CD4+ T cells confers suppressive function [31]. Because Foxp3 amounts were reduced in foxp3gfpBim−/− and foxp3gfpvav-Bcl-2 Treg cells we assessed if their suppressive potential might be impaired in an in vitro suppression assay system. Therefore, CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells were stimulated either alone or in the presence of genotype matched Treg cells. Treg cells from all genotypes were able to suppress their matching Tcon cells but while suppression of wild type or Bim−/− Tcon cells seemed similar, that of vav-Bcl-2 Tcon cells was clearly less efficient (Fig. 4A). This marked difference may be related to changes in function or responsiveness of nTreg and/or Tcon cells overexpressing Bcl-2 that may include increased survival (Fig. 2) and/or inferior proliferative capacity (not shown).

Fig. 4.

Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells display reduced suppressive capacity in vitro. Different ratios of splenic CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg and CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb (2C11) for 3 days. T cell proliferation was assessed by [H3]-thymidine incorporation added during the last 16 h of cell culture. Proliferation was normalized to Tcon cell proliferation in the absence of Treg cells. (A) Proliferation of wild type (n = 19), Bim−/− (n = 6) or vav-Bcl-2 (n = 9) Tcon cells in the absence or presence of Treg cells with the same genotype. (B) Proliferation of wild type (n = 19), Bim−/− (n = 7) or vav-Bcl-2 (n = 9) Tcon cells cultured in the absence or presence of wt Treg cells. (C) Wild type Tcon cells were used as responder T cells and cultured with or without wild type (n = 19), Bim−/− (n ≥ 6) or vav-Bcl-2 (n = 9) Treg cells. (D) wt Tcon cells were cultured alone or with wt Foxp3-GFPhigh (n = 4), unseparated vav-Bcl-2 (Foxp3-GFPall) (n = 4) Tregs or vav-Bcl-2 Tregs divided into Foxp3-GFPhigh (n = 3) and Foxp3-GFPlow Tregs cells (n = 4). Data points represent means ± SEM; statistics: Student’s t-test *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

It has been proposed that responder T cells can differ in their susceptibility to Treg cell mediated suppression when cell death is impaired [18]. Thus, we cultured wild type, Bim-deficient or vav-Bcl-2 transgenic Tcon cells together with wild type Treg cells and assessed their proliferation capacity. Proliferation of Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Tcon cells was efficiently suppressed in the presence of wild type Treg cells (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, suppression of Bim−/− Tcon cells by wild type Treg cells was even more efficient than that of wild type or vav-Bcl-2 Tcon cells when limiting dilution experiments were performed. While the reasons for the increased susceptibility of Bim-deficient CD4+ T cells over those expressing transgenic Bcl-2 remain to be identified, our observations demonstrate that induction of apoptosis in Tcon cells does not play a significant role in suppression, as most recently also noted by Vignali et al. [32].

Keeping in mind that Bim-deficient T cells were reported to be more anergic and to respond more reluctantly to antigenic challenge [33], we reasoned that differences in Treg cell function may become distinguishable when apoptosis-defective Treg cells needed to suppress functionally fully competent responder T cells. In line with this hypothesis, when wild type Tcon cells were incubated with Bim−/− or vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells a clear-cut difference was observed, as both genotypes were less effective in suppressing wild type Tcon cells, when compared to controls (Fig. 4C). The suppressive capacity of vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells was weakest and this phenotype correlated with lower levels of Foxp3 in these cells, a phenomenon also noted in Bim−/− Treg cells, albeit less pronounced (Fig. 3). To assess if Foxp3 expression directly impacts on Treg cell function we divided vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells in Foxp3-GFPhigh and Foxp3-GFPlow groups and compared their suppressive potential with that of unseparated (Foxp3-GFPall) and wild type Treg cells that all showed high levels of GFP expression (Foxp3-GFPhigh) (Fig. 4C). Indeed, Foxp3-GFPlow vav-Bcl-2 Tregs were weaker in the suppression of Tcon cells compared to all other Treg subpopulations. Surprisingly, Foxp3-GFPhigh vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells were still less potent when compared to wild type Foxp3-GFPhigh Treg cells (Fig. 4D), indicating that the levels of Foxp3 in these cells do not define suppressive capacity alone. Impaired function becomes best apparent when apoptosis-defective Treg cells are challenged with fully competent CD4+ responder T cells. Hence deregulation of Bcl-2 family protein levels in Treg cells may contribute to inflammatory phenotypes frequently underlying autoimmunity.

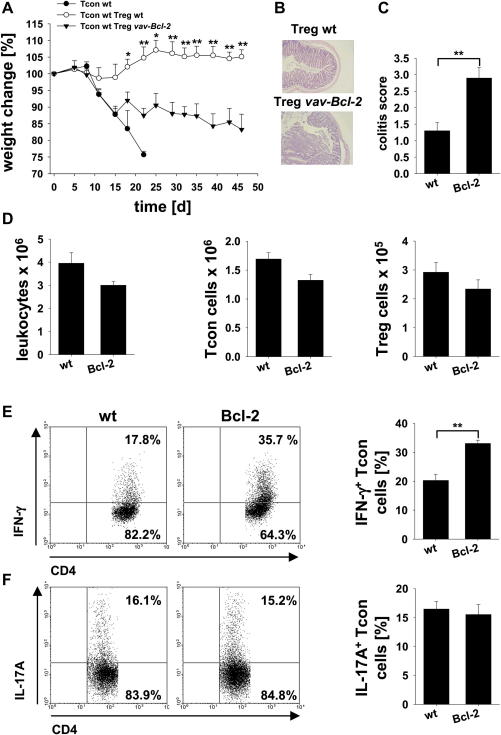

3.5. Bcl-2 transgenic Treg cells fail to effectively suppress inflammatory bowel disease

To evaluate if vav-Bcl-2 derived Treg cells also display an impaired suppressive function in vivo we tested their capacity to prevent T cell induced colitis. Therefore, 4 × 105 CD4+Foxp3-GFP− wild type conventional T cells were transferred alone (control group) or together with 1 × 105 CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ wild type or vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells into RAG1−/− mice. Animals receiving only Tcon cells without Treg cells rapidly developed colitis, indicated by strong weight loss and had to be sacrificed early on, displaying a colitis score of 3, according to histopathological assessment (Fig. 5A; not shown). Transfer of wild type Treg cells successfully prevented development of colitis during the whole observation period whereas mice receiving vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells succumbed to disease, initially even as quickly as mice that only received conventional CD4+ T cells (Fig. 5A). However, after two weeks their weight loss decelerated, suggesting at least a partial suppression of disease by vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells but animals never fully recovered during the whole observation period (Fig. 5A–C). Animals were sacrificed after 7 weeks. Consistent with a pro-inflammatory phenotype, total splenic cellularity was significantly increased in animals that received vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells compared to wild type controls due to an increase in Mac-1+ cells (not shown), while the number of conventional CD4+ T and Treg cells remained comparable (Suppl. Fig. 3A). Notably, significantly more IFN-γ producing CD4+ Tcon cells were found in the mesenteric lymph nodes of mice treated with Treg cells overexpressing Bcl-2 than mice that received wild type cells while no difference was observed in IL-17 production (Fig. 5E, F). Mesenteric lymph node cellularity (Fig. 5D) and IFN-γ or IL-17 secretion in spleen were indistinguishable between the groups (Suppl. Fig. 3B). Together, these findings strongly support the pathophysiological relevance of deregulated mitochondrial cell death signalling in Treg cell function, warranting a more detailed analysis of Bcl-2 family protein expression in Treg cells from patients with autoimmune disease.

Fig. 5.

vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells fail to effectively prevent induction of colitis. Colitis was induced in RAG1−/− mice by adoptive transfer of 4 × 105 wild type CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells without (control group; n = 3) or together with 1 × 105 wild type (n = 4) or vav-Bcl-2 CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells (n = 4). Animals were sacrificed when weight loss reached >25% (control group) or on day 46 after cell transfer (mice receiving either wild type or vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells). (A) Depicted is the relative weight change normalized to the starting weight before cell transfer. (B) Representative H&E stained mid-colon sections and (C) colitis score of mice treated with wild type Tcon cells, either together with wild type or vav-Bcl-2 CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells. (D) Absolute cell number (left panel), Tcon (middle panel) and Treg cell number (right panel) in the mesenteric lymph nodes of mice receiving wild type Tcon cells either together with wild type (wt) or vav-Bcl-2 (Bcl-2) Treg cells. Expression of (E) IFN-γ and (F) IL-17A by CD4+Foxp3-GFP− Tcon cells in the mesenteric lymph node after 5 h stimulation in vitro in the presence of PMA/Ionomycin has been analyzed by intracellular staining and flow cytometry. Data points represent means ± SEM; one out of two independent experiments is shown; statistics: Student’s t-test *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01.

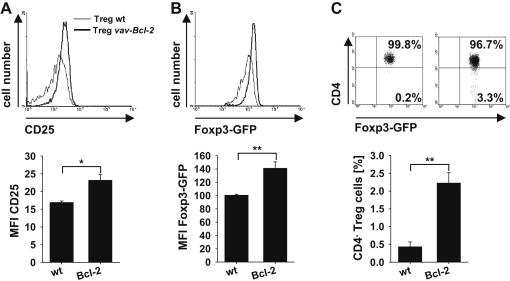

3.6. Inflammation can restore the suppressive capacity of Bcl-2 overexpressing Treg cells

To assess which impact the ongoing inflammatory response had in relation to the delayed recovery of mice that received Bcl-2 transgenic Treg cells, we also compared expression of Foxp3-GFP, CD25, GITR and CTLA-4 in wild type and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells before and after transfer. Treg cells in the spleen of vav-Bcl-2 mice displayed significantly reduced levels of Foxp3-GFP, CD25 and GITR (Fig. 3), but surprisingly the opposite phenotype was observed 7 weeks after disease induction (Fig. 6A, B). While GITR was now comparable between wild type and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells (Suppl. Fig. 4D, E), Foxp3 as well as CD25 expression were even significantly higher in vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells (Fig. 6A, B and Suppl. Fig. 4A, B). In addition, when these cells were tested in an in vitro suppression assay, wild type and vav-Bcl-2 Treg both efficiently suppressed wt Tcon cells (Suppl. Fig. 4F). This indicates that reduced Treg cell lineage marker expression and suppression capacity by vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells do not result from a cell intrinsic developmental defect as these deficiencies can be overcome under pro-inflammatory conditions. Notably here, as in vav-Bcl-2 mice, we also observed the emergence of CD4−Foxp3-GFP+ vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells after transfer into RAG1−/− mice (Fig. 6C and Suppl. Fig. 4C). This suggests that defective cell death signalling allows their undesired survival after exhaustion that associates with phenotypic changes.

Fig. 6.

Bcl-2 overexpressing Treg cells express higher levels of Foxp3 and CD25 than wild type Treg cells under inflammatory conditions. On day 46 after cell transfer mice were sacrificed and expression of (A) CD25, (B) Foxp3-GFP and (C) CD4 by wild type and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes was assessed by flow cytometry. For the quantification of CD25 and Foxp3-GFP expression, cells were gated on CD4+Foxp3-GFP+ and for CD4 expression on total Foxp3-GFP+ Treg cells. In the upper panel representative histograms or dot plots from one out of four representative stainings are depicted. The lower panels display quantification of CD25 MFI, Foxp3-GFP MFI and CD4− Treg cells. Bars represent means ± SEM of n = 4 animals per group; statistics: Student’s t-test *p ≤ 0.05 **p ≤ 0.01.

4. Discussion

In this study, we assessed how Bcl-2 regulated apoptosis impacts on Treg cell apoptosis susceptibility, maturation, phenotype and functionality. Our RT-MLPA expression analysis demonstrates that Treg cells differ from Tcon cells in their repertoire of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins expressed that contribute to differences in their susceptibility to apoptosis induced by different stimuli (Figs. 1 and 2). Proteins of the Bcl-2 family are critically involved in T cell selection and maturation processes in the thymus. For example Mcl-1 and A1 are induced upon cytokine and (pre)TCR signalling in immature double negative thymocytes [34,35] and Bcl-xL becomes the major survival protein in double-positive thymocytes where Bcl-2 levels become repressed [36] and Bim executes negative selection [37]. Contrary to conventional CD4+ T cells, Treg cells require a stronger TCR signal for development in the thymus and are more resistant to negative selection compared to conventional CD4+ T cells [38,39]. This idea is also supported by our results. Levels of Bcl-xL were found higher and those for Bim were reduced, circumventing negative selection. Higher Mcl-1 and A1 levels may result from strong TCR signalling received during negative selection and may be required to antagonize the simultaneous increase in Noxa levels observed in these cells (Fig. 1).

In the periphery Treg cells also differ from Tcon cells in expression levels of proteins of the Bcl-2 family. Most notably, Bcl-xL that is usually downregulated in mature T cells and replaced by Bcl-2 [36] was found increased, indicating either stimulation by self-peptide ligands in the periphery and/or cytokine stimulation by IL-2 via constitutive expression of CD25 on Treg cells. These differences may also account for the observed increased survival of splenic Treg cells in response to dexamethasone, etoposide or staurosporine. At least for the observed glucocorticoid resistance a former study correlated augmented Bcl-2 levels and IL-2 with survival advantages in Treg cells in response to dexamethasone treatment [40]. In general, loss of pro-apoptotic Bim or overexpression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 increased survival of both Treg and Tcon cells alike, indicating conserved function of the Bcl-2 proteins family in both cell types.

Next to the increased survival capacity in response to the aforementioned stimuli Tregs were more susceptible to cytokine deprivation, HDAC-inhibition and Fas ligation. As Treg cells cannot produce IL-2 [30] or IL-7 [41] they are highly susceptible to cytokine deprivation. Thus, either loss of Bim or Bcl-2 overexpression, as well as addition of common γ-chain cytokines IL-2 or IL-7, rescued Treg cells from apoptosis (Fig. 2). Former studies reported that HDAC-inhibitors induce Treg cell maturation in vivo. Increased acetylation of Foxp3 increased its binding to the IL-2 promoter thereby suppressing cytokine production [42]. However, HDAC-inhibition can also lead to the induction of Bim in lymphoid tumor cells [43] and, as shown here, ultimately triggers apoptosis also in Treg cells. As noted before, Treg cells were found highly susceptible to apoptosis induction by Fas ligation that may be due to higher Fas surface expression by Treg cells compared to Tcon cells (Ref. [44] and Tischner et al., pers. observation). Notably, expression of Noxa mRNA was found also to be much higher in splenic Treg cells, as opposed to Tcon cells. Since Noxa expression can be induced by antigenic stimulation in peripheral CD8+ T cells [45], we assume that stimulation by self-peptide/MHC molecules may contribute to this phenotype but protein levels achieved appear insufficient to cause death. However, increased Noxa may prime Treg cells to apoptosis, e.g. as it does conventional T cells under glucose limiting conditions [46].

Similar to observations made with conventional T cells [8], Treg cell number was augmented in Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 mice. Notably, some of these cells developed into double negative Treg cells in the thymus that were then also found in the periphery (Fig. 3). Cells in the thymus seem to derive from SP4+ Treg cells, as they also stain positive for the TCR-beta chain on their surface (not shown) and presumably escaped negative selection. These observations are in line with most recent findings by Zhan et al. who provided evidence that these cells are actually autoreactive cells that have been reprogrammed/redirected to commit to an anergic regulatory T cell fate [47].

Notably, Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells showed reduced expression of Foxp3, CD25, GITR and CTLA-4, the latter only in the thymus (Fig. 3), suggesting that these cells may not be fully functional which was confirmed in vitro (Fig. 4) and in vivo (Fig. 5). While we, and others [32], failed to note substantial differences in genotype matched suppression assays, arguing against the cytokine consumption hypothesis for T cell suppression [18], we also realized that Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells displayed a reduced suppressive capacity towards Tcon cells from wild type mice (Fig. 4). However, attempts to define differences in calcium signalling, known to be modulated by Bcl-2 [48], in Treg cells were unsuccessful, questioning an intrinsic defect. Yet, vav-Bcl-2 Treg cells showed also a strongly impaired suppressive capacity in vivo (Fig. 5). However, isolated colitogenic vav-Bcl-2 transgenic Treg cells from these mice showed even higher levels of CD25 and Foxp3 expression, when compared to wild type cells (Fig. 6) and were equally potent in suppressing Tcon cells in vitro (Suppl. Fig. 4C). As this phenomenon coincided with increased total splenocyte number and IFN-γ production by Tcon cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes (Fig. 5), we assume that the reduced suppressive capacity of Treg cells in vav-Bcl-2 mice is not cell intrinsic and can be overcome during inflammation. Consistently, addition of IL-2 in vitro was shown to increase Foxp3 expression in Bim-deficient Treg cells [47], in line with IL-2 signalling impacting directly on Foxp3 promoter activity [49]. However, as mice never fully recovered their initial body weight over a period of 7 weeks, we assume that Bcl-2 transgenic Treg cells may be able to recover only transiently or carry additional defects that affect the biological outcome (Fig. 5).

Another open question is why these “disabled” Treg cells develop in Bim−/− and vav-Bcl-2 mice in the first place and where they originate. Zhan and colleagues propose that these cells accumulate in such large number because they represent survivors of negative selection deviated into an anergic Treg cell fate when mitochondrial cell death is impaired. Consistently, these cells more frequently expressed self-reactive TCRs against endogenous superantigens and display low level CD25 expression, presumably as they do no longer depend strictly on IL-2 for survival [47]. However, our study shows that additional Treg cells lacking CD4 expression do accumulate in the thymus (Fig. 3C) and that these cells can also arise de novo from CD4+ Treg cells during suppression of T cell expansion in vivo (Fig. 6). We assume that these cells also represent a pool of cells that should have been deleted, either in the thymus during negative selection, or towards the end of an immune response in the periphery. Whether these cells are still functional remains to be determined.

5. Conclusions

Collectively, our findings demonstrate that cell death along the intrinsic Bcl-2 regulated apoptosis pathway is critical for normal development and function of Treg cells. Intrinsic differences in Bcl-2 family protein expression impinge on the relative cell death susceptibility of Treg cells to a number of stress signals that may become of pathophysiological importance, such as those elicited by glucocorticoids or cytokine withdrawal. Deregulated expression of key effectors of the Bcl-2 family impairs lineage commitment and suppressive capacity but these defects are not imprinted and appear largely reversible during conditions of inflammation. Therefore, attempts to increase the yield or lifespan of Treg cells prior therapeutic application by modulation of cell death regulators should be feasible without significantly compromising their regulatory capacity, albeit a certain caveat remains, warranting further detailed investigations.

Authorship contribution

D.T. designed and performed most experiments, statistical analysis, prepared figures and wrote paper. I.G., I.P., M.K. and S.T. performed experiments. M.D. performed histopathological assessment. A.V. designed research, interpreted data, wrote paper, conceived study. G.J.W. performed experiments, designed research, interpreted data and wrote paper. A.V. and G.J.W. contributed equally to this study.

Disclosure of conflicts

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K. Rossi and C. Soratroi for animal care and technical assistance as well as to G. Böck for cell sorting. We thank H. Acha-Orbea, J. Adams and A. Strasser for mice and reagents; M. Erlacher for help with MLPA analysis. This work was supported by grants from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF); SFB021 and START Y212-B12 to A.V.; the Tiroler Krebshilfe to J.G.W. and the Daniel Swarovski Fond to D.T.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2011.12.008.

Contributor Information

Andreas Villunger, Email: andreas.villunger@i-med.ac.at.

G. Jan Wiegers, Email: jan.wiegers@i-med.ac.at.

Appendix. Supplementary material

References

- 1.Strasser A. The role of BH3-only proteins in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:189–200. doi: 10.1038/nri1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rieux-Laucat F., Le Deist F., Fischer A. Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndromes: genetic defects of apoptosis pathways. Cell Death Diff. 2003;10:124–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tischner D., Woess C., Ottina E., Villunger A. Bcl-2-regulated cell death signalling in the prevention of autoimmunity. Cell Death Dis. 2010;1:e48. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2010.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strasser A., Harris A.W., Bath M.L., Cory S. Novel primitive lymphoid tumours induced in transgenic mice by cooperation between myc and bcl-2. Nature. 1990;348:331–333. doi: 10.1038/348331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campbell K.J., Bath M.L., Turner M.L., Vandenberg C.J., Bouillet P., Metcalf D. Elevated Mcl-1 perturbs lymphopoiesis, promotes transformation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells and enhances drug-resistance. Blood. 2010 doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egle A., Harris A.W., Bath M.L., O’Reilly L., Cory S. VavP-Bcl2 transgenic mice develop follicular lymphoma preceded by germinal center hyperplasia. Blood. 2004;103:2276–2283. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strasser A., Whittingham S., Vaux D.L., Bath M.L., Adams J.M., Cory S. Enforced BCL2 expression in B-lymphoid cells prolongs antibody responses and elicits autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:8661–8665. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.19.8661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouillet P., Metcalf D., Huang D.C.S., Tarlinton D.M., Kay T.W.H., Köntgen F. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative Bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science (New York, N.Y.) 1999;286:1735–1738. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutcheson J., Scatizzi J.C., Siddiqui A.M., Haines G.K., 3rd, Wu T., Li Q.Z. Combined deficiency of proapoptotic regulators Bim and Fas results in the early onset of systemic autoimmunity. Immunity. 2008;28:206–217. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doreau A., Belot A., Bastid J., Riche B., Trescol-Biemont M.C., Ranchin B. Interleukin 17 acts in synergy with B cell-activating factor to influence B cell biology and the pathophysiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:778–785. doi: 10.1038/ni.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehrian R., Quismorio F.P., Jr., Strassmann G., Stimmler M.M., Horwitz D.A., Kitridou R.C. Synergistic effect between IL-10 and bcl-2 genotypes in determining susceptibility to systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:596–602. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199804)41:4<596::AID-ART6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu L.F., Rudensky A. Molecular orchestration of differentiation and function of regulatory T cells. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1270–1282. doi: 10.1101/gad.1791009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mucida D., Pino-Lagos K., Kim G., Nowak E., Benson M.J., Kronenberg M. Retinoic acid can directly promote TGF-beta-mediated Foxp3(+) Treg cell conversion of naive T cells. Immunity. 2009;30:471–472. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.008. [author reply 472–473] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vignali D.A., Collison L.W., Workman C.J. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wing K., Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells exert checks and balances on self tolerance and autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:7–13. doi: 10.1038/ni.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren X., Ye F., Jiang Z., Chu Y., Xiong S., Wang Y. Involvement of cellular death in TRAIL/DR5-dependent suppression induced by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. Cell Death Diff. 2007;14:2076–2084. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strauss L., Bergmann C., Whiteside T.L. Human circulating CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells kill autologous CD8+ but not CD4+ responder cells by Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 2009;182:1469–1480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pandiyan P., Zheng L., Ishihara S., Reed J., Lenardo M.J. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induce cytokine deprivation-mediated apoptosis of effector CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1353–1362. doi: 10.1038/ni1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gambineri E., Torgerson T.R., Ochs H.D. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked inheritance (IPEX), a syndrome of systemic autoimmunity caused by mutations of FOXP3, a critical regulator of T-cell homeostasis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:430–435. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brunkow M.E., Jeffery E.W., Hjerrild K.A., Paeper B., Clark L.B., Yasayko S.A. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:68–73. doi: 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahl K., Loddenkemper C., Drouin C., Freyer J., Arnason J., Eberl G. Selective depletion of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells induces a scurfy-like disease. J Exp Med. 2007;204:57–63. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huan J., Culbertson N., Spencer L., Bartholomew R., Burrows G.G., Chou Y.K. Decreased FOXP3 levels in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:45–52. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar M., Putzki N., Limmroth V., Remus R., Lindemann M., Knop D. CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T lymphocytes fail to suppress myelin basic protein-induced proliferation in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;180:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haribhai D., Lin W., Relland L.M., Truong N., Williams C.B., Chatila T.A. Regulatory T cells dynamically control the primary immune response to foreign antigen. J Immunol. 2007;178:2961–2972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogilvy S., Metcalf D., Print C.G., Bath M.L., Harris A.W., Adams J.M. Constitutive bcl-2 expression throughout the hematopoietic compartment affects multiple lineages and enhances progenitor cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14943–14948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ranger A.M., Zha J., Harada H., Datta S.R., Danial N.N., Gilmore A.P. Bad-deficient mice develop diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9324–9329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533446100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Labi V., Erlacher M., Krumschnabel G., Manzl C., Tzankov A., Pinon J. Apoptosis of leukocytes triggered by acute DNA damage promotes lymphoma formation. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1602–1607. doi: 10.1101/gad.1940210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Villunger A., Michalak E.M., Coultas L., Mullauer F., Bock G., Ausserlechner M.J. p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins puma and noxa. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2003;302:1036–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1090072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eldering E., Spek C.A., Aberson H.L., Grummels A., Derks I.A., de Vos A.F. Expression profiling via novel multiplex assay allows rapid assessment of gene regulation in defined signalling pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fontenot J.D., Rasmussen J.P., Gavin M.A., Rudensky A.Y. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fontenot J.D., Rasmussen J.P., Williams L.M., Dooley J.L., Farr A.G., Rudensky A.Y. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szymczak-Workman A.L., Delgoffe G.M., Green D.R., Vignali D.A. Cutting edge: regulatory T cells do not mediate suppression via programmed cell death pathways. J Immunol. 2011;187:4416–4420. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ludwinski M.W., Sun J., Hilliard B., Gong S., Xue F., Carmody R.J. Critical roles of Bim in T cell activation and T cell-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J Clin Investig. 2009;119:1706–1713. doi: 10.1172/JCI37619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opferman J.T., Letai A., Beard C., Sorcinelli M.D., Ong C.C., Korsmeyer S.J. Development and maintenance of B and T lymphocytes requires antiapoptotic MCL-1. Nature. 2003;426:671–676. doi: 10.1038/nature02067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandal M., Borowski C., Palomero T., Ferrando A.A., Oberdoerffer P., Meng F. The BCL2A1 gene as a pre-T cell receptor-induced regulator of thymocyte survival. J Exp Med. 2005;201:603–614. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ma A., Pena J.C., Chang B., Margosian E., Davidson L., Alt F.W. Bclx regulates the survival of double-positive thymocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4763–4767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bouillet P., Purton J.F., Godfrey D.I., Zhang L.-C., Coultas L., Puthalakath H. BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim is required for apoptosis of autoreactive thymocytes. Nature. 2002;415:922–926. doi: 10.1038/415922a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aschenbrenner K., D’Cruz L.M., Vollmann E.H., Hinterberger M., Emmerich J., Swee L.K. Selection of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells specific for self antigen expressed and presented by Aire+ medullary thymic epithelial cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:351–358. doi: 10.1038/ni1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moon J.J., Dash P., Oguin T.H., 3rd, McClaren J.L., Chu H.H., Thomas P.G. Quantitative impact of thymic selection on Foxp3+ and Foxp3− subsets of self-peptide/MHC class II-specific CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14602–14607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109806108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen X., Murakami T., Oppenheim J.J., Howard O.M. Differential response of murine CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells to dexamethasone-induced cell death. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:859–869. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guimond M., Veenstra R.G., Grindler D.J., Zhang H., Cui Y., Murphy R.D. Interleukin 7 signaling in dendritic cells regulates the homeostatic proliferation and niche size of CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:149–157. doi: 10.1038/ni.1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tao R., de Zoeten E.F., Ozkaynak E., Chen C., Wang L., Porrett P.M. Deacetylase inhibition promotes the generation and function of regulatory T cells. Nat Med. 2007;13:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/nm1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindemann R.K., Newbold A., Whitecross K.F., Cluse L.A., Frew A.J., Ellis L. Analysis of the apoptotic and therapeutic activities of histone deacetylase inhibitors by using a mouse model of B cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8071–8076. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702294104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weiss E.M., Schmidt A., Vobis D., Garbi N., Lahl K., Mayer C.T. Foxp3-mediated suppression of CD95L expression confers resistance to activation-induced cell death in regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:1684–1691. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wensveen F.M., van Gisbergen K.P., Derks I.A., Gerlach C., Schumacher T.N., van Lier R.A. Apoptosis threshold set by Noxa and Mcl-1 after T cell activation regulates competitive selection of high-affinity clones. Immunity. 2010;32:754–765. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alves N.L., Derks I.A., Berk E., Spijker R., van Lier R.A., Eldering E. The Noxa/Mcl-1 axis regulates susceptibility to apoptosis under glucose limitation in dividing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:703–716. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhan Y., Zhang Y., Gray D., Carrington E.M., Bouillet P., Ko H.J. Defects in the Bcl-2-regulated apoptotic pathway lead to preferential increase of CD25 low Foxp3+ anergic CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:1566–1577. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rong Y., Distelhorst C.W. Bcl-2 protein family members: versatile regulators of calcium signaling in cell survival and apoptosis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:73–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.021507.105852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zorn E., Nelson E.A., Mohseni M., Porcheray F., Kim H., Litsa D. IL-2 regulates FOXP3 expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells through a STAT-dependent mechanism and induces the expansion of these cells in vivo. Blood. 2006;108:1571–1579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.