Abstract

Microvesicles (MVs) are released by most cell types in physiological conditions, but their number is often increased upon cellular activation or neoplastic transformation. This suggests that their detection may be helpful in pathological conditions to have information on activated cell types and, possibly, on the nature of the activation. This could be of paramount importance in districts and tissues that are not accessible to direct examination, such as the central nervous system. Increased release of MVs has been described to be associated to the acute or active phase of several neurological disorders. While the subcellular origin of MVs (exosome or ectosomes) is basically never addressed in these studies because of technical limitations, the cell of origin is always identified. Endothelium- or platelet-derived MVs, detected in plasma or serum, are linked to neurological pathologies with a vascular or ischemic pathogenic component, and may represent a very useful marker to support therapeutic choices in stroke. In neuroinflammatory disorders, such as multiple sclerosis, MVs of oligodendroglial, or microglial origin have been described in the cerebrospinal fluid and may carry, in perspective, additional information on the biological alterations in their cell of origin. Little specific evidence is available in neurodegenerative disorders and, specifically, MVs of neural origin have never been investigated in these pathologies. Few data have been reported for neuroinfection and brain trauma. In brain tumors, despite the limited number of studies performed, results are very promising and potentially close to clinical translation. We here review all currently available data on the detection of MVs in neurological diseases, limiting our search to exclusively human studies. Current literature and our own data indicate that MVs detection may represent a very promising strategy to gain pathogenic information, identify therapeutic targets, and select specific biomarkers for neurological disorders.

Keywords: microvesicles, neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, brain tumors, neurological disorders

Introduction

Microvesicles (MVs) have gained recently large attention as both potential biomarkers, and a tool to investigate the biology of cells from sites difficult to reach in vivo. Solid tumors, for example, display an elusive nature of transformed cells, grow into organs, and re-appear in unpredictable sites when producing metastases. By releasing massive amounts of MVs, however, they may reveal their presence. Investigating the content of these vesicles, information may be gained on biological processes occurring within the tumor mass. Similarly, in diseases of the central nervous system (CNS), a part from post-mortem examination, neuroscientists, and neurologists do not have access to the diseased tissue with the extreme exception of cases that need a cerebral biopsy, which are usually not representative of the most common neurological disorders. Therefore, here also, MVs, that are physiologically released by all neural and non-neural cells within the CNS (Figure 1), hold promise as possible vehicle of clinical and biological information. The difficulties related to the detection and analysis of MVs in neurological disorders are partially overlapping with those found in other diseases, and partially peculiar. In fact there are common problems of general inadequacy of available detection techniques. It is now a general consensus that flow cytometry (FACS) is unable to detect properly small exosomes (Figure 2), but only can reliably analyze ectosomes (Figure 2), also called shed vesicles. Further, as compared to tumor cells, platelets, or endothelial cells, neural cells release very reduced amounts of MVs, posing also a problem of detection limit. Finally, the most interesting compartment to examine, the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), cannot be sampled serially without posing an ethical problem. Nevertheless, the possibility to access these complex cargo structures, storing a multiplicity of signals derived from un-accessible cells, gives the possibility to get very relevant information on their cell of origin during disease. Upon proper interpretation, these evidences may yield data with clinical diagnostic and prognostic value, provide information to stratify patients concerning response to treatments, or even suggest new therapeutic targets.

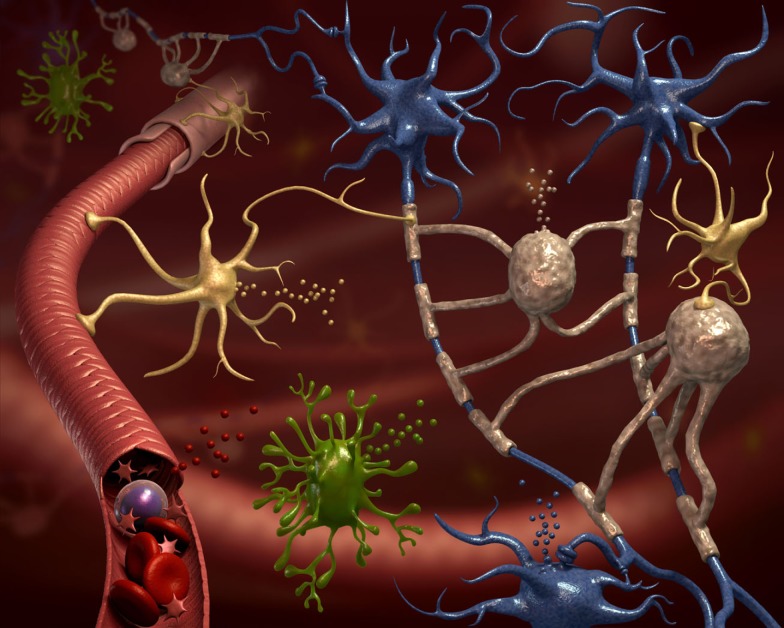

Figure 1.

All neural cell types release microvesicles (MVs). The CNS parenchyma is very complex in terms of cellular composition. This cartoon depicts neurons (blue cells), their axons surrounded by myelin produced by oligodendrocytes (gray cells), ramified microglia (green cells), astrocytes (yellow cells), and blood vessels (in red). Still, this is a very simplified representation of CNS tissue. All represented, and not represented, cell types are able to release MVs delivering signals to neighboring cells and into the environment (van der Vos et al., 2011). Some of these MVs are drained to accessible biological fluids like the blood or the cerebrospinal fluid, where they might constitute a new class of biomarkers.

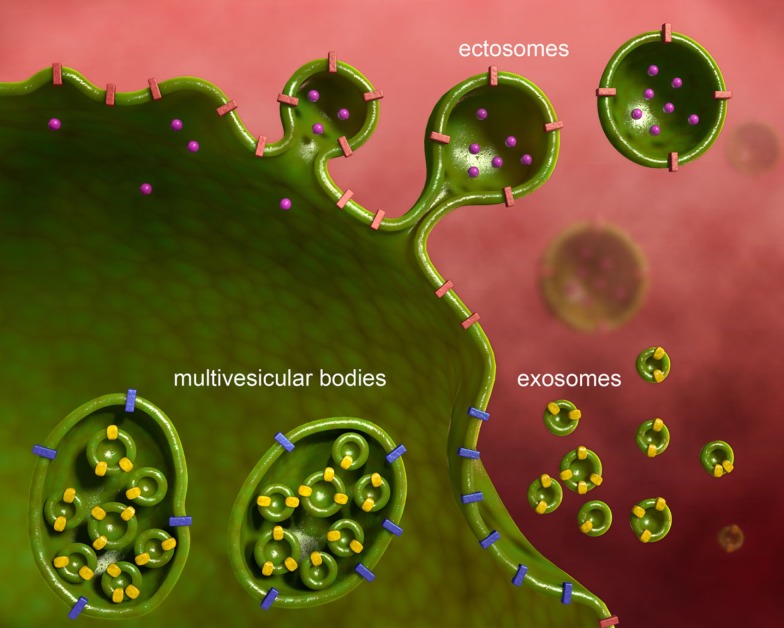

Figure 2.

Microvesicles are of different subcellular origin. MVs released from various neural cell types have different subcellular origin. In the present review we consider ectosomes, also called shed vesicles, and exosomes. Ectosomes shed from the plasma membrane carrying along transmembrane proteins, and soluble proteins, nucleic acids, and metabolites present in the cytoplasm. Ectosomes are large and heterogeneous in size. Exosomes derive from the release of multivesicular bodies, an intracellular organel along the endocytic pathway, that controls membrane composition and content. Exosomes are small and homogenous in size.

Investigations have already been performed in this respect and we are going to review available evidence for MVs of different cellular and subcellular origin, and detected by different techniques, in different compartments, as potential biomarkers in neurological disorders (Table 1).

Table 1.

MVs in neurological diseases.

| Disease | Site and detection | Cell of origin | MPs modulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEREBROVASCULAR DISORDERS | ||||

| Ischemic stroke | Plasma by FACS | Platelets | ↑ CD42+ | Lee et al. (1993) |

| Ischemic stroke | Blood by FACS | Platelets | ↑ CD61+ ↑ CD62P+ |

Cherian et al. (2003), Pawelczyk et al. (2008) |

| Ischemic stroke | Plasma by ELISA | Platelets | ↑ CD42a+ | Shirafuji et al., 2008 |

| Ischemic stroke | Plasma by ELISA | Platelets | ↑ CD42+ | Kuriyama et al. (2010) |

| Ischemic stroke | Plasma by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD105+CD41a−CD45− | Simak et al. (2006) |

| ↑ CD105+CD144+ | ||||

| ↑ CD105+PS+CD41a | ||||

| ↑ CD105+CD54+CD45 | ||||

| Strokes mimics | Plasma by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD31+ | Williams et al. (2007) |

| ↑ CD62E+ | ||||

| Intracranial arterial stenosis | Plasma by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD31+CD42b | Jung et al. (2009) |

| ↑ CD31+PS+ | ||||

| Extracranial arterial stenosis | Plasma by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD62E+ | Jung et al. (2009) |

| Cerebral vasospasm | Plasma by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD105+PS+ | Lackner et al. (2010) |

| ↑ CD62E+ | ||||

| ↑ CD106+ | ||||

| Cerebral infarction following vasospasm | Plasma by FACS | Platelets | ↑ CD41+ | Lackner et al. (2010) |

| NEUROINFLAMMATORY DISEASES | ||||

| Multiple sclerosis | CSF by electron microscopy | Oligodendrocytes | ↑ Unknown | Scolding et al. (1989) |

| Multiple sclerosis | Plasma by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD31+CD42− | Minagar et al. (2001) |

| ↑ CD51+ | ||||

| Multiple sclerosis | Blood by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD54+ | Jy et al. (2004) |

| ↑ CD62E+ | ||||

| Multiple sclerosis | Plasma by FACS | Platelets | ↑ CD62P+ | Sheremata et al. (2008) |

| Cerebral malaria | Plasma by FACS | Endothelium | ↑ CD51+ | Combes et al. (2004) |

| NEURODEGENERATIVE DISORDERS | ||||

| Alzheimer | CSF by WB | Neurons? | ↑ Phospho-tau | Saman et al. (2012) |

| Alzheimer | Blood by FACS | Platelets | No modulation | Lee et al. (1993), Sevush et al. (1998) |

| Vascular dementia | Plasma by FACS | Platelets | ↑ CD42+ | Lee et al. (1993) |

| EPILEPSY | ||||

| Temporal lobe epilepsy | CSF by immunoblotting | Stem cells | ↑ CD133+ | Huttner et al. (2012) |

| BRAIN TUMORS | ||||

| Glioblastoma | Biopsies by electron microscopy | Tumor cells | ↑ Membrane blebs | González-Cámpora et al. (1978) |

| Glioblastoma | CSF by immunoblotting | Stem cells | ↑ CD133+ | Huttner et al. (2008) |

| Glioblastoma | Serum and biopsies by RT-PCR | Tumor cells | ↑ EGFRvIII+ | Skog et al. (2008) |

| TRAUMA | ||||

| Traumatic brain injury | CSF and plasma by prothrombinase assay | Platelets and endothelium | ↑ CD42+ ↑ CD31+ |

Morel et al. (2008) |

Cerebrovascular Disorders

The number of MVs derived from endothelial cells or platelets have been linked to the extent of myocardial infarcts (Mallat et al., 2000; Jung et al., 2012). Similarly, their number has been investigated by several groups in cerebral ischemia.

Already in the early 1990s, Ahn and co-workers found that platelet-derived MVs, stained for CD42 and detected by FACS, are increased in plasma of patients with ischemic stroke, especially in those with transitory ischemic attacks or with lacunar infarcts, as compared to those with thrombosis of large vessels (Lee et al., 1993). In this first, pioneering study, however, no correlations had been drawn with the extent of the ischemic area, or the severity of the outcome (Lee et al., 1993). These results have been confirmed, over 10 years later, using CD61 and CD62P to identify MVs of platelets origin, in whole blood of patients with ischemic stroke (Cherian et al., 2003; Pawelczyk et al., 2009). These two reports discuss their results associating increased platelet activation, testified by the increased release of MVs, with higher risk of developing stroke. They therefore propose to use the detection of platelet-derived MVs as a biomarker to be used in a population at risk to have a stroke, to identify individuals with higher chance, or particularly close to develop the event. Two groups in Japan have used an interesting, alternative, technical approach to overcome some of the limitations of flow cytometry in measuring platelet-derived MVs. By ELISA they quantify the platelet marker CD42a or CD42 on ultracentrifugated plasma MVs, confirming the positive association of these markers with the occurrence of ischemic stroke (Shirafuji et al., 2008; Kuriyama et al., 2010). From these studies we can conclude that platelet-derived MVs are studied to dissect the contribution of platelets to the pro-thrombotic state leading to stroke, but, judging from available literature, appear of limited clinical usefulness as biomarkers.

Endothelium-derived MVs, recently identified and linked to cerebral ischemia, may be more promising. The first available report associated the number of endothelial MVs, identified in plasma by FACS staining for CD105, CD144, phosphadityl serine (PS), and CD54, with several clinical parameters, including stroke size, severity, and outcome (Simak et al., 2006). In particular, lesion volume appeared to be in direct correlation with the number of CD105+, CD54+, PS+, but not CD144+ MVs. CD144+ MVs, on the other hand, predict the hemorrhagic transformation of the ischemic lesion (Simak et al., 2006). Contrasting results were reported 1 year later, when similar CD31+ or CD62E+endothelial MVs levels were described in acute ischemic stroke patients and in stroke mimics, i.e., patients with stroke-like symptoms but apparently without ischemic lesions (Williams et al., 2007). The lack of a real consensus on the definition of stroke mimics (potentially affected by transitory ischemic attack?), and several technical limitations, including the use of archival samples stored frozen for over 1 year, however, limit the interpretation of these data. More recently, Jung et al. (2009) have substantially confirmed the original finding. In fact, they describe elevated endothelium-derived MVs to be significantly associated to stenosis of both intra- and extra-cranial portions of cerebral arteries. Further they associate distinct MVs markers for extra-cranial (CD62E+) and intra-cranial (CD31+CD42b−PS+) localization of the stenosis. This study also confirms a positive correlation of the number of plasma endothelial MVs and infarct size and clinical severity. Analysis of predictive parameters in patients already carrying risk factors showed that plasma levels of endothelial MVs were inversely correlated with the time of occurrence of an ischemic stroke (Jung et al., 2009). The predictive value of endothelial MVs (defined as CD105+PS+, CD62E+, or CD106+), has been confirmed in a different clinical setting, namely the risk to develop cerebral vasospasm in patients with spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage (Lackner et al., 2010), in which also platelet-derived MVs may play a role (Lackner et al., 2010). The recent introduction of treatments of the acute phase of ischemic stroke, for example systemic thrombolysis, indicates the need for biomarkers able to stratify patients and minimize side effects of these therapies. Further, the identification of patients in which the risk for ischemic stroke is so high that it might be worth treating with anticoagulants could be a very powerful preventive strategy. Plasma endothelial MVs levels may potentially represent a solid biomarker for these two conditions. Investigations to validate this concept are conducted in several centers.

Neuroinflammatory Diseases

With the introduction of MRI, and especially gadolinium-enhanced MRI, the field of neuroinflammation has found a gold standard biomarker providing localization, structural (or even ultrastructural), molecular, and functional information. Performances of MRI are still increasing and its potential has not been fully exploited, since new sequences, providing new information, are constantly developed. What is the need, then, for new biomarkers in neuroinflammation? MRI is very costly, difficult to perform on all patients in the emergency room, and, for the moment, provides very little information on the biological status of single cell types. MVs hold the potential to fill this gap, providing quantitative and qualitative information on distinct cell types selectively involved in CNS pathologies.

The pioneering work in this field was published over 20 years ago, describing MVs of oligodendroglial origin in the CSF of patients affected by multiple sclerosis (MS; Scolding et al., 1989). Authors discussed their findings in the perspective of dissecting the effector mechanisms leading to myelin destruction, rather than as potential biomarkers for MS. The reason, among others, may rely on the fact that CSF is not a readily accessible biological fluid and repeated sampling, as mentioned above, poses an ethical issue. On the other hand, inflammatory events occurring in the CNS may produce biomarkers that are rapidly diluted in the circulation and difficult to detect in peripheral fluids, such as plasma, displaying high background noise levels for most markers. Nevertheless, CD31+ endothelial MVs, identified in plasma samples by FACS, have been associated to clinical and neuroradiological exacerbation of MS, while CD51+ endothelial MVs have been found elevated in both relapsing and remitting MS patients as compared to controls (Minagar et al., 2001). The same group has confirmed their findings in 2004, further describing that most endothelial MVs can be detected in the blood in the form of conjugates with other cells, especially monocytes (Jy et al., 2004), while described that, similarly to stroke, platelet-derived MVs, despite elevated in the plasma of MS patients as compared to controls, display a reduced discriminating power between health and disease (Sheremata et al., 2008).

Endothelium-derived MVs have been investigated also in cerebral malaria, a complication of malaria occurring in about 1% of patients infected with Plasmodium Falciparum and in which the endothelium of small cerebral vessels appears to play a crucial role (Milner, 2010). Indeed, endothelial MVs, detected by FACS staining for CD51, are selectively increased in plasma of patients with cerebral malaria and in patients with both coma and severe anemia, as compared to patients with uncomplicated malaria or only with severe anemia (Combes et al., 2004). Further, the number of plasma endothelial MVs normalizes upon treatment, suggesting a possible role also as biomarkers for therapeutic efficacy (Combes et al., 2004).

A common feature of all neuroinflammatory diseases is the primary involvement of the prototypical immune neural cell type: microglia. Practically indistinguishable from peripheral tissue macrophages using common markers, not accessible due to anatomical reasons, the only current way to gain information on microglia activation in vivo is by positron emission tomography using the tracer [11C](R)-PK11195 (Kannan et al., 2009). We have recently described that microglia derived MVs, identified by FACS staining for IB4, are dramatically increased in the CSF of patients with neuroinflammatory diseases such as patients affected by relapsing MS, neuromyelitis optica, meningitis (RF and CV personal communication). Our clinical and experimental data suggest that microglial MVs may be a solid marker for disease status and response to therapies, with all the limitations of biomarkers in the CSF that we have discussed above.

Neurodegenerative Disorders

Little evidence is available in the literature for MVs alterations in neurodegeneration. In Alzheimer’s disease, negative results for platelet-derived MVs have been reported, demented patients displaying MVs levels overlapping to healthy individuals (Lee et al., 1993; Sevush et al., 1998). A very recent report, however, describes that in early Alzheimer it is possible to detect increased levels of phosphorylated tau protein in the exosome fraction of the CSF (Saman et al., 2012). This is a very promising finding, and points to the possibility for an early diagnosis of AD through CSF MVs content. For amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, experimental data in vitro on mice tissue suggest the possible increase in motoneuron-derived apoptotic MVs (Appert-Collin et al., 2006), but no human follow-up studies have been performed. Thus, the only positive available evidence is for vascular, multi-infarct, dementia in which elevated platelet-derived MVV have been reported (Lee et al., 1993), in line with data available for cerebral ischemia, of which vascular dementia is a chronic form. Since so little work has been done so far, neurodegeneration appears, in perspective, an interesting field to investigate MVs.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is, of course, mostly a clinical diagnosis and is monitored by electroencephalography. Stratification of patients in clinical subtypes is, however, not always trivial. Notably, MVs positive for the stem cell marker prominin-1/CD133, likely derived from neural stem cells or ependymal cells, have been found elevated in the CSF of patients with partial temporal, but not extra-temporal, epilepsy (Huttner et al., 2012). CD133+ MVs CSF levels were similarly increased in cryptogenetic forms or in patients were temporal epilepsy was secondary to neoplasms dysplasia, or hippocampal sclerosis (Huttner et al., 2012).

Brain Tumors

Brain tumor diagnosis and monitoring is usually performed by neuroradiology, with the need in certain circumstances to perform an invasive cerebral biopsy. A pioneering work by Roy Weller and collaborators, suggested already in 1978 the existence of glioblastoma-derived MVs (Gonzalez-Campora et al., 1978). In fact, by scanning electron microscopy they described, on human glioblastoma biopsy samples, the presence of several membrane alterations such as microvilli, blebs, and ruffles, suggesting a high motility of cell membranes. MVs close to shed from the cell membrane are clearly depicted in electron scans of this work (Gonzalez-Campora et al., 1978). Evidence for glioblastoma-derived MVs in biological fluids are, however, very recent. Huttner et al. (2008) have quantified, by immunoblotting, prominin-1/CD133+in MVs purified by ultracentrifugation from CSF samples. They show that prominin-1/CD133 levels are very high in CSF MVs from patients with glioblastoma as compared to healthy individuals. More useful in a clinical setting may be the finding by Skog et al. (2008) that it is possible to detect, by nested PCR, the transcript coding for the oncogenic form of the epidermal growth factor receptor EGFRvIII in MVs purified by ultracentrifugation from serum of a subgroup of patients with glioblastoma. This opens the possibility to use a serum biomarker, carried by glioblastoma-derived MVs, to support diagnosis in case of uncertain neuroradiological images, by avoiding invasive procedures such as cerebral biopsy, and to monitor therapeutic efficacy or the appearance of recurrences.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Traumatic brain injury may, besides acute lesions, determine secondary cellular and vascular damage leading to poor clinical outcome. Morel and co-authors described that in the CSF and in the plasma of patients with traumatic brain injury, PS+ MVs, defined as pro-coagulant by a functional assay, increase and peak in the acute phase, returning to basal levels within 10 days (Morel et al., 2008). The cellular origin of these MVs has been defined by capturing them with platelet and endothelial plastic-bound specific antibodies. Patients with persistent high CSF levels of these MVs displayed a poor clinical outcome. Thus, CSF endothelial or platelet-derived MVs may help identify those traumatic patients that need special care because of their high risk to develop secondary events leading to a fatal outcome or severe neurological deficit.

Conclusion

As can be learned from this review, MVs have not been widely investigated as potential biomarkers in neurological disorders, although the first evidence of their existence in the CNS was provided several decenniums ago. The most striking limit of current available reports is that, apart from glioblastoma tumor cells, MVs from very few, actually only two CNS specific cell types have been investigated for release in humans, namely oligodendrocytes and microglia. In fact, most studies mentioned in this review deal with MVs released by endothelium or platelets, and translate to the brain concepts that had been developed principally for myocardial infarct. The main reason for this may rely on the fact that, in general, neural cells generally release low amounts of MVs as compared to endothelium, platelets, stem cells, or tumor cells. Therefore, brain specific MVs are very diluted, if present, in peripheral biological fluids such as blood, plasma, or serum, thus making very difficult their detection by current available technologies. On the other hand, endothelium and platelets, and even microglia, are involved in most pathological processes occurring within the CNS. Thus, even if detected in the CSF, MVs derived from these cell types are likely to be non-specifically altered in the course of different neurological diseases.

Nevertheless, detection of MVs as biomarkers for neurological disorders is very promising in perspective. The development of new detection systems, specifically designed for MVs, with increased sensitivity and able to stratify MVs according to size and cellular origin, may considerably improve our ability to associate a certain MVs pattern to a specific pathological condition. The main goal to gain disease specificity is, however, identification of the content of MVs. It is reasonable to think that MVs of neural origin carry different molecules in different diseases and even in different disease phases. Further, the unique possibility to obtain from MVs in vivo information on brain cells involved in pathological processes may shed light on the pathogenesis of currently elusive pathologies such as primary neurodegenerative disorders, i.e., Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, ALS, etc. In some of these disorders MVs themselves may play a role in pathogenesis, and thus constitute a novel therapeutic target, once the biology of their release will be dissected in more detail (Bianco et al., 2009).

From the neurologist’s perspective, validated, routinely available, detection techniques for MVs may be very interesting in stroke, where they may constitute an additional paraclinical parameter to evaluate when deciding therapeutic strategies, or to identify patients at high risk for a poor clinical outcome. In brain tumors the possibility to avoid brain biopsy and to monitor disease progression through MVs only depends from the detection limits, since tumor-specific MVs bearing specific markers have already been identified, and may indeed constitute a valuable tool in future clinical neurology. In neuroinflammation the role for MVs may be more difficult to define, since solid biomarkers, such as MRI, are already available, and microglial MVs in the CSF, despite holding promise, may remain a non-specific parameter, helpful but not decisive to make diagnosis and difficult to use for monitoring. Detection of MVs from neural cell origin may be extremely useful in neuroinfection, especially in those cases were the pathogen may be elusive, since it is known that MVs are carriers for infectious agents, and isolation of MVs from the CSF may help to increase significantly the sensitivity of available tests.

In conclusion, MVs already represent an interesting biomarker in neurology. To make their detection a routine procedure in the clinics, we need a change of gears in the development of specific technologies able to increase the performances of currently available assays. This would probably allow also more investigations in neglected fields like neurodegeneration, that however constitute one of the major challenges for research in medical neurosciences.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. Brown and Dr. L. Muzio for helpful discussion. This work was supported by the Italian Foundation for Multiple Sclerosis (FISM201/R/39) and the Italian Ministry of Research (2008XFMEA3).

References

- Appert-Collin A., Hugel B., Levy R., Niederhoffer N., Coupin G., Lombard Y., Andre P., Poindron P., Gies J. P. (2006). Cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors prevent apoptosis of postmitotic mouse motoneurons. Life Sci. 79, 484–490 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco F., Perrotta C., Novellino L., Francolini M., Riganti L., Menna E., Saglietti L., Schuchman E. H., Furlan R., Clementi E., Matteoli M., Verderio C. (2009). Acid sphingomyelinase activity triggers microparticle release from glial cells. EMBO J. 28, 1043–1054 10.1038/emboj.2009.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherian P., Hankey G. J., Eikelboom J. W., Thom J., Baker R. I., Mcquillan A., Staton J., Yi Q. (2003). Endothelial and platelet activation in acute ischemic stroke and its etiological subtypes. Stroke 34, 2132–2137 10.1161/01.STR.0000086466.32421.F4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combes V., Taylor T. E., Juhan-Vague I., Mege J. L., Mwenechanya J., Tembo M., Grau G. E., Molyneux M. E. (2004). Circulating endothelial microparticles in malawian children with severe falciparum malaria complicated with coma. JAMA 291, 2542–2544 10.1001/jama.291.21.2542-a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Campora R., Haynes L. W., Weller R. O. (1978). Scanning electron microscopy of malignant gliomas. A comparative study of glioma cells in smear preparations and in tissue culture. Acta Neuropathol. 41, 217–221 10.1007/BF00690439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner H. B., Corbeil D., Thirmeyer C., Coras R., Köhrmann M., Mauer C., Kuramatsu J. B., Kloska S. P., Doerfler A., Weigel D., Klucken J., Winkler J., Pauli E., Schwab S., Hamer H. M., Kasper B. S. (2012). Increased membrane shedding – indicated by an elevation of CD133-enriched membrane particles – into the CSF in partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 99, 101–106 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner H. B., Janich P., Köhrmann M., Jaszai J., Siebzehnrubl F., Blumcke I., Suttorp M., Gahr M., Kuhnt D., Nimsky C., Krex D., Schackert G., Lowenbruck K., Reichmann H., Juttler E., Hacke W., Schellinger P. D., Schwab S., Wilsch-Brauninger M., Marzesco A. M., Corbeil D. (2008). The stem cell marker prominin-1/CD133 on membrane particles in human cerebrospinal fluid offers novel approaches for studying central nervous system disease. Stem Cells 26, 698–705 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C., Sörensson P., Saleh N., Arheden H., Rydén L., Pernow J. (2012). Circulating endothelial and platelet derived microparticles reflect the size of myocardium at risk in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Atherosclerosis 221, 226–231 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K. H., Chu K., Lee S. T., Park H. K., Bahn J. J., Kim D. H., Kim J. H., Kim M., Kun Lee S., Roh J. K. (2009). Circulating endothelial microparticles as a marker of cerebrovascular disease. Ann. Neurol. 66, 191–199 10.1002/ana.21681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jy W., Minagar A., Jimenez J. J., Sheremata W. A., Mauro L. M., Horstman L. L., Bidot C., Ahn Y. S. (2004). Endothelial microparticles (EMP) bind and activate monocytes: elevated EMP-monocyte conjugates in multiple sclerosis. Front. Biosci. 9, 3137–3144 10.2741/1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S., Balakrishnan B., Muzik O., Romero R., Chugani D. (2009). Positron emission tomography imaging of neuroinflammation. J. Child Neurol. 24, 1190–1199 10.1177/0883073809338063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama N., Nagakane Y., Hosomi A., Ohara T., Kasai T., Harada S., Takeda K., Yamada K., Ozasa K., Tokuda T., Watanabe Y., Mizuno T., Nakagawa M. (2010). Evaluation of factors associated with elevated levels of platelet-derived microparticles in the acute phase of cerebral infarction. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 16, 26–32 10.1177/1076029609338047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner P., Dietmann A., Beer R., Fischer M., Broessner G., Helbok R., Marxgut J., Pfausler B., Schmutzhard E. (2010). Cellular microparticles as a marker for cerebral vasospasm in spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke 41, 2353–2357 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.584995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J., Jy W., Horstman L. L., Janania J., Reyes Y., Kelley R. E., Ahn Y. S. (1993). Elevated platelet microparticles in transient ischemic attacks, lacunar infarcts, and multiinfarct dementias. Thromb. Res. 72, 295–304 10.1016/0049-3848(93)90138-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat Z., Benamer H., Hugel B., Benessiano J., Steg P. G., Freyssinet J. M., Tedgui A. (2000). Elevated levels of shed membrane microparticles with procoagulant potential in the peripheral circulating blood of patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 101, 841–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner D. A., Jr. (2010). Rethinking cerebral malaria pathology. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23, 456–463 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833c3dbe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minagar A., Jy W., Jimenez J. J., Sheremata W. A., Mauro L. M., Mao W. W., Horstman L. L., Ahn Y. S. (2001). Elevated plasma endothelial microparticles in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 56, 1319–1324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel N., Morel O., Petit L., Hugel B., Cochard J. F., Freyssinet J. M., Sztark F., Dabadie P. (2008). Generation of procoagulant microparticles in cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood after traumatic brain injury. J. Trauma. 64, 698–704 10.1097/TA.0b013e31816493ad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelczyk M., Baj Z., Chmielewski H., Kaczorowska B., Klimek A. (2009). The influence of hyperlipidemia on platelet activity markers in patients after ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 27, 131–137 10.1159/000177920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saman S., Kim W., Raya M., Visnick Y., Miro S., Jackson B., Mckee A. C., Alvarez V. E., Lee N. C., Hall G. F. (2012). Exosome-associated tau is secreted in tauopathy models and is selectively phosphorylated in cerebrospinal fluid in early Alzheimer disease. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3842–3849 10.1074/jbc.M111.277061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolding N. J., Morgan B. P., Houston W. A., Linington C., Campbell A. K., Compston D. A. (1989). Vesicular removal by oligodendrocytes of membrane attack complexes formed by activated complement. Nature 339, 620–622 10.1038/339620a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevush S., Jy W., Horstman L. L., Mao W. W., Kolodny L., Ahn Y. S. (1998). Platelet activation in Alzheimer disease. Arch. Neurol. 55, 530–536 10.1001/archneur.55.4.530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheremata W. A., Jy W., Horstman L. L., Ahn Y. S., Alexander J. S., Minagar A. (2008). Evidence of platelet activation in multiple sclerosis. J. Neuroinflammation 5, 27. 10.1186/1742-2094-5-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirafuji T., Hamaguchi H., Kanda F. (2008). Measurement of platelet-derived microparticle levels in the chronic phase of cerebral infarction using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 54, E55–E61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simak J., Gelderman M. P., Yu H., Wright V., Baird A. E. (2006). Circulating endothelial microparticles in acute ischemic stroke: a link to severity, lesion volume and outcome. J. Thromb. Haemost. 4, 1296–1302 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01911.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skog J., Wurdinger T., Van Rijn S., Meijer D. H., Gainche L., Sena-Esteves M., Curry W. T., Jr., Carter B. S., Krichevsky A. M., Breakefield X. O. (2008). Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1470–1476 10.1038/ncb1800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vos K. E., Balaj L., Skog J., Breakefield X. O. (2011). Brain tumor microvesicles: insights into intercellular communication in the nervous system. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 31, 949–959 10.1007/s10571-011-9697-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. B., Jauch E. C., Lindsell C. J., Campos B. (2007). Endothelial microparticle levels are similar in acute ischemic stroke and stroke mimics due to activation and not apoptosis/necrosis. Acad. Emerg. Med. 14, 685–690 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2007.tb01861.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]