Abstract

PURPOSE

We sought to identify and compare studies reporting the prevalence of multimorbidity and to suggest methodologic aspects to be considered in the conduct of such studies.

METHODS

We searched the literature for English- and French-language articles published between 1980 and September 2010 that described the prevalence of multimorbidity in the general population, in primary care, or both. We assessed quality of included studies with a modified version of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist. Results of individual prevalence studies were adjusted so that they could be compared graphically.

RESULTS

The final sample included 21 articles: 8 described studies conducted in primary care, 12 in the general population, and 1 in both. All articles were of good quality. The largest differences in prevalence of multimorbidity were observed at age 75 in both primary care (with prevalence ranging from 3.5% to 98.5% across studies) and the general population (with prevalence ranging from 13.1% to 71.8% across studies). Apart from differences in geographic settings, we identified differences in recruitment method and sample size (primary care: 980–60,857 patients; general population: 1,099–316,928 individuals), data collection, and the operational definition of multimorbidity used, including the number of diagnoses considered (primary care: 5 to all; general population: 7 to all). This last aspect seemed to be the most important factor in estimating prevalence.

CONCLUSIONS

Marked variation exists among studies of the prevalence of multimorbidity with respect to both methodology and findings. When undertaking such studies, investigators should carefully consider the specific diagnoses included and their number, as well as the operational definition of multimorbidity.

Keywords: prevalence, multimorbidity, comorbidity, primary care, general population, family practice, chronic disease, practice-based research

INTRODUCTION

As a result of various factors, including aging of the population and advances in medical care and public health policy, a growing proportion of patients have multiple coexisting chronic diseases, also referred to as multimorbidity.1,2 Because of the negative consequences and high cost associated with multimorbidity, it has received growing interest in the primary care literature over the past few years and is now acknowledged by some as a research priority.3–7 At a time when several countries are undergoing major primary care reforms, multimorbidity appears to be a driver of change as it implies a shift in health services from the single-disease paradigm from which the majority of medical knowledge arises to a more holistic view of patients and a “generalist approach” to care.8

Unlike single chronic diseases or conditions for which strong epidemiologic data are available, however, results for multimorbidity vary widely among studies, making it difficult to determine whether differences among countries and locations and between the general and primary care populations are real or due to a wide variety of methodologic issues. Considering the importance of valid descriptive data, this area of research deserves greater attention.9 In this systematic review, we evaluate prevalence studies on multimorbidity and highlight the differences and possible explanations for variations among them. Our aim was to identify and compare studies reporting the prevalence of multimorbidity, and to suggest methodologic aspects to be considered in the conduct of such studies.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria

We searched for articles meeting both of 2 inclusion criteria: they described the prevalence of multimorbidity or reported results that allowed its calculation, and they reported studies conducted in primary care, in the general population, or both.

Search Strategy and Article Selection

We conducted an electronic literature search of the Ovid MEDLINE and MANTIS databases for English- and French-language articles published between 1980 and September 2010. The strategy was run in both databases simultaneously, and duplicates were eliminated (as shown in Supplemental Appendix 1, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/10/2/142/suppl/DC1). We used 4 Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): prevalence, chronic disease, primary health care, and family practice; we also used the key words multimorbidity and its lexical and nonlexical linguistic variation multi-morbidity, multiple diseases, prevalence study, general practice, and population. To broaden the scope of our research, we also applied the search strategy to the same databases using the MeSH comorbidity and its linguistic variation co-morbidity. We also examined reference lists for additional relevant articles.

One team member (J.A.) read the abstract to exclude articles that were not eligible. Two authors (J.A. and M-E.P.) independently appraised the full text of the retrieved papers. Articles meeting all inclusion criteria were retained for quality assessment and data extraction. Discrepancies between the 2 reviewers were resolved by team consensus.

Assessment of Study Quality

We assessed study quality with a modified version of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (available at http://www.strobe-statement.org/fileadmin/Strobe/uploads/checklists/STROBE_checklist_v4_cross-sectional.pdf).10,11 The checklist was modified to include items that should be considered in reports of cross-sectional studies. Each reviewer (J.A. and M-E.P.) independently determined a global quality score for each article, giving 1 point for each STROBE item the article addressed. To be retained in our review, articles had to have a quality score of at least 12 out of a possible 23.

Data Extraction and Calculations

We extracted all data related to multimorbidity prevalence or its calculation from the included articles. As multimorbidity is strongly associated with older ages, and there was no uniformity in the way age and sex were reported in the articles, we made the following age-related adjustments so that we could display all prevalence studies in a single graph for comparison (one for primary care and one for the general population).

If prevalence was reported for an age range, we calculated mean age between the lower and upper limits to represent the range in the graph.

If prevalence was reported for an age range with an upper limit only, we adjusted the age to approximately 10 years below the upper limit to represent the range. For example, if the age was either 25 years or younger, or younger than 25 years, we used an age of 15 years.

If prevalence was reported for an age range with a lower limit only, we adjusted the age to approximately 10 years above the lower limit to represent the range. For example, if the age was either 70 years or older, or older than 70 years, we used an age of 80 years.

If prevalence was reported for male and female individuals separately, we calculated the weighted mean value of both groups to represent the prevalence in the graph.

RESULTS

Articles Included in the Review

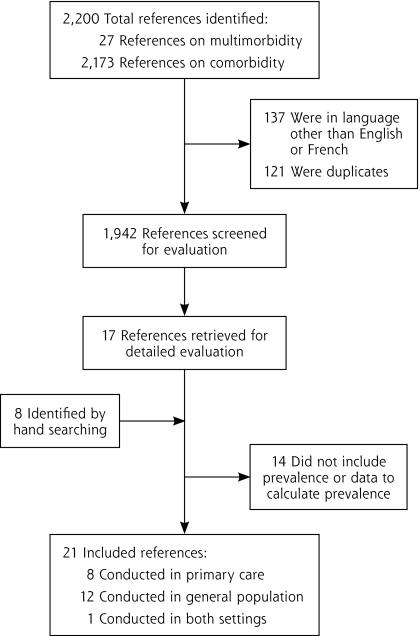

Our process for selecting articles is shown in Figure 1. The search strategies identified 27 references with the word multimorbidity and 2,173 with the word comorbidity, of which 1,942 remained after removing articles written in languages other than English or French and duplicates. After the abstracts were read for eligibility, 17 articles were retained to be read completely; 8 more were identified by reviewing reference lists. Of these 25 publications, 4 were excluded because they did not contain prevalence information or data allowing its calculation. The final sample used for data extraction and calculations was thus 21 articles: 8 containing prevalence information in primary care,1,2,12–17 12 in the general population,18–29 and 1 in both settings.30

Figure 1.

Number of references identified at each stage of the systematic review.

Study quality was assessed in all but 2 publications that were not research articles, one a statistical report28 and the other a chartbook.29 Quality scores in the final sample of articles ranged from 15 to 23 out of 23 (as shown in Supplemental Appendix 2, available at http://www.annfammed.org/content/10/2/142/suppl/DC1); therefore, all articles were retained.

Primary Care Settings

The primary care articles reported prevalence in the Netherlands,1,2,15,30 the United Kingdom,14,16 Canada,13 Australia,12 and Greece.17 Table 1 shows characteristics of those reporting prevalence estimates of 2 or more coexisting chronic conditions. One article reported the prevalence based on 2 or more domains of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) affected by chronic diseases.12 The CIRS makes it possible to classify any illness within 1 of the 14 organ system domains of the instrument, simplifying coding down to 14 possible domains. Britt and colleagues12 have proposed that multimorbidity be defined as involvement of 2 or more organ domains by chronic diseases.

Table 1.

Studies Reporting Prevalence of Multimorbidity in Primary Care Settings

| Sample | Methods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Year) | Country | No. of Patients | Age, y | Recruitment | Data Collection | No. of Diagnoses Considered |

| Schellevis et al (1993)15 | The Netherlands | 23,534 | All | Patients registered in 7 general practices | Medical history from patient records | 5 |

| van den Akker et al (1998)1 | The Netherlands | 60,857 | All | Patients included in the Registration Network of Family Practices (15 practices) | Medical history from computerized database | ICPC codes related to diagnostic categories |

| Macleod et al (2004)16 | United Kingdom | 7,286 | ≥18 | Patients registered in a practice | Medical history from computerized database | 8 major diseases |

| Fortin et al (2005)13 | Canada | 980 | ≥18 | Patients in the waiting room of 21 family physicians | Medical history from patient records | All |

| Kadam et al (2007)14 | United Kingdom | 9,439 | ≥50 | Responders to a survey who consulted their GP before the survey | Medical history from patient records | 185 morbidities categorized on 4 ordinal scales of severity |

| Schram et al (2008)30 | The Netherlands | 2,895 (setting 1), 5,610 (setting 2) | ≥55 | Patients from 2 GP registries, 1 of 4 general practices with 10 GPs and another of 4 general practices with 20 GPs | Medical history from patient records | 68 morbidities (setting 1) and 83 morbidities (setting 2), with >2% prevalence |

| Uijen and van de Lisdonk (2008)2 | The Netherlands | 13,584 | All | Patients included in the Primary Care Research Network, 4 practices (10 GPs) | Medical history from patient records | All chronic diseases with an ICHPPC code except very rare conditions |

| Britt et al (2008)12 | Australia | 9,156 | All | Patients attending 305 GPs | GPs recorded morbidity, using their knowledge of patients, patient self-report, and medical records | 18 morbidities or categories classified into 8 CIRS morbidity domains and 1 additional domain for malignancies |

| Minas et al (2010)17 | Greece | 20,299 | >14 | Patients visiting 4 primary health care centers and willing to participate | Structured questionnaires completed by study coordinators who also checked medical records | All chronic diseases; diseases recorded were included in their respective organ system according to ICPC codes |

CIRS = Cumulative Illness Rating Scale; GP = general practitioner; ICHPPC = International Classification of Health Problems in Primary Care; ICPC = International Classification of Primary Care.

The studies were heterogeneous in terms of recruitment methods, sample size, data collection, and operational definition of multimorbidity or comorbidity. Three studies sampled patients from those consulting their family physician,12,13,17 whereas the others included all patients from the selected practices. The number of participants in each study varied tremendously, from 980 to 60,857. In 2 studies, data were collected using chart review13,14; in the others, data were collected from a registry or an electronic health record. With regard to the operational definition of multimorbidity and comorbidity, the main source of variation was the number of diseases considered in the count (5, 8, 68, 83, 185, or all possible chronic conditions) regardless of the data collection approach used. The definition of a chronic condition varied among studies, and the importance or severity of the disease was usually not specified. All publications defined multimorbidity as having 2 or more chronic diseases (or 2 or more affected CIRS domains) and reported results accordingly, but the majority also reported other cutoffs such as 3 or more, or 4 or more.2,12,13,15–17,30 One article reported the number of patients with chronic diseases in more than 2 domains of the CIRS without weighting for severity.12

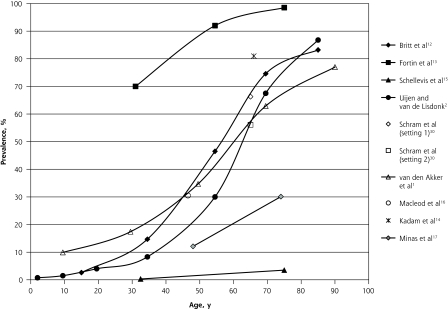

Figure 2 summarizes the prevalence estimates reported by these studies based on a count of 2 or more chronic diseases (or CIRS domains) according to age and shows a wide variation in the results, the only constant being the increasing prevalence with age. The largest difference in prevalence (Δ = 95.0%) was observed at age 75 years, with prevalence ranging from 3.5% in a study reporting on 5 chronic diseases15 to 98.5% in another reporting on all chronic diseases.13 Among studies that included patients of all ages, there was an S-shaped curve for the association between age and prevalence: prevalence was roughly 20% or lower before the age of 40 years, then increased dramatically, and finally plateaued around the age of 70 years at 75%.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of multimorbidity (defined as ≥2 diseases) reported in primary care settings.

Note: Data reported in the studies were adjusted to fit into the graph, as described in the Methods section.

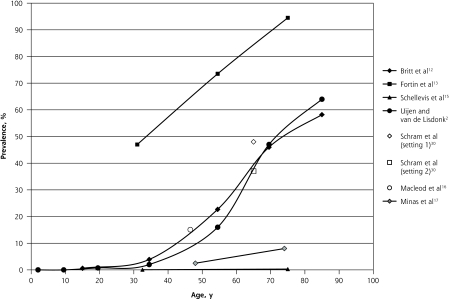

Figure 3 shows the results for studies reporting results with a cutoff of 3 or more chronic diseases used to define multimorbidity. The S-shaped curves are still evident, although the curves are less pronounced and more linear, with an overall lower prevalence as expected. The 2 studies looking at broad age ranges reported increasing numbers of chronic conditions with advancing age.1,13

Figure 3.

Prevalence of multimorbidity (defined as ≥3 diseases) reported in primary care settings.

Note: Data reported in the studies were adjusted to fit into the graph, as described in the Methods section.

General Population

Studies of the general population reported either national or local prevalence of multimorbidity in the United States,22,24,27,29 Canada,25,28 Israel,26 Ireland,23 Germany,21 Sweden,19 the Netherlands,30 and Spain.18 One article gathered data from sites in Finland, Italy, and the Netherlands.20 Table 2 shows the characteristics of articles reporting prevalence estimates of 2 or more coexisting chronic conditions in the general population.

Table 2.

Studies Reporting Prevalence of Multimorbidity in the General Population

| Sample | Methods | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (Year) | Country | No. of Individuals | Age, y | Recruitment | Data Collection | No. of Diagnoses Considered |

| Verbrugge et al (1989)27 | United States | 16,148 | ≥55 | 1984 National Health Interview Survey, the Supplement on Aging | Questionnaire completed by interview | 13 |

| Newacheck et al (1991)24 | United States | 7,465 | 10–17 | 1988 National Health Interview Survey on Child Health | Questionnaire completed by interview | >50 |

| Hoffman et al (1996)22 | United States | 27,505 | All | 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey | Questionnaire completed by interview | All chronic conditions classified in ICD-9 codes |

| Fuchs et al (1998)26 | Israel | 1,487 | 75–94 | A national random stratified sample | Questionnaire completed by interview | 14 |

| Menotti et al (2001)20 | Finland, The Netherlands, Italy | 716 (Finland), 887 (the Netherlands), and 682 (Italy) | Men 65–84 | Cohorts recruited in particular locations | Clinical examination | 7 |

| Rapoport et al (2004)25 | Canada | 17,244 | >20 | 1999 National Population Health Survey | Questionnaire completed by interview | 22 |

| Partnership for Solutions (2004)29 | United States | (Not reported) | All | 2001 National Medical Expenditure Survey | Questionnaire completed by interview | All chronic conditions classified in ICD-9 codes |

| Naughton et al (2006)23 | Ireland | 316,928 | Individuals from a national pharmacy claims database | Conditions identified from ≥3 dispensed items associated with a specific chronic condition | 9 | |

| Nagel et al (2008)21 | Germany | 13,781 | 50–75 | Participants in the EPIC subcohort of Heidelberg recruited from the general population | Questionnaire completed by interview | 13 diagnostic groups |

| Marengoni et al (2008)19 | Sweden | 1,099 | 77–100 | Inhabitants of the Kungsholmen area in Stockholm | Clinical assessment, medical history, laboratory data, and current drug use | All chronic conditions |

| Schram et al (2008)30 | The Netherlands | 1,691+1,002 (LASA), 7,983 (Rotterdam), and 599 (Leiden) | 55–94 (LASA), ≥65 (Rotterdam), 85 (Leiden) | Inhabitants of the different geographic locations | Medical history from self-reports as well as from the GP (LASA); an extensive physical examination (Rotterdam); medical history obtained from GP or treating nursing home physician (Leiden) | Varied by location: 12 diagnoses (LASA), 12 diagnoses (Rotterdam), and 13 diagnoses (Leiden) |

| Cazale and Dumitru (2008)28 | Canada | ~26,000 | ≥12 | Quebec residents included in the 2005 National Population Health Survey | Questionnaire completed by interview | 7 |

| Loza et al (2009)18 | Spain | 2,192 | >20 | National random sample taking into account the Spanish rural-urban ratio | Questionnaire completed by interview | All diseases |

EPIC = European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; GP = general practitioner; ICD-9=International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; LASA=Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam.

As for the primary care studies, these studies varied considerably in their recruitment methods, sample sizes, data collection methods, and operational definitions of multimorbidity. Participants consisted of national random samples,18,22,24–29 cohorts in particular geographic locations,19–21,30 or individuals identified from national pharmacy claims databases.23 The sample size again varied widely, from 1,099 to 316,928 individuals. Most studies used a questionnaire18,21,22,24–29; other methods were clinical assessment,19,20,30 medical history obtained from a health professional,30 and use of a pharmacy database to identify conditions.23

The number of reported conditions varied from 7 to any number, with variation in the criteria used to define them. All studies considered a count of 2 diseases or more as multimorbidity. Many studies included chronic conditions without regard for their severity, masking considerable variation in disease burden for patients.

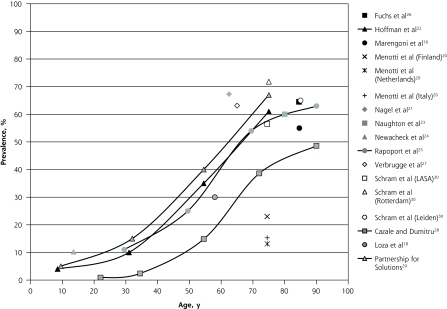

Figure 4 depicts the prevalence estimates reported in these general population studies according to age. Again, the highest variation in prevalence (Δ = 58.7%) was observed at age 75, with values ranging from 13.1%20 to 71.8%30 across studies; of note, both studies reported data from the Netherlands. The studies assessing individuals across broad age ranges showed S-shaped curves for prevalence by age, similar to those found in the primary care settings.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of multimorbidity (≥2 diseases) in the general population.

LASA = Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam.

Note: Data reported in the studies were adjusted to fit into the graph, as described in the Methods section

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review shows that prevalence estimates of multimorbidity vary widely among studies. The largest difference was observed at the age of 75 years both in primary care and in the general population (Δ across studies = 95% and 59%, respectively). Differences of this magnitude are unlikely to reflect real differences between populations and more likely to be due to biases in methods. In addition to their differing geographic settings, the studies differed in recruitment method and sample size, data collection, and operational definition of multimorbidity, including the number of conditions and the conditions selected. All of these factors may affect prevalence estimates.

Impact of Methodology

The majority of studies conducted in primary care used existing patient databases. These cohorts have the advantage of including a very large number of diverse patients.2,15,16,30 Their prevalence estimates are probably a good representation of the actual prevalence at the primary care level in their respective locations, provided that a random sample of practices is included; however, the reliability of these estimates can be affected by factors such as the completeness of records and how data are codified.

In contrast, studies wherein patients are recruited during a visit with the physician may overrepresent frequent attenders, who have more complex medical problems and would increase the apparent prevalence of multimorbidity observed in the practice. This phenomenon may explain why 3 of the 4 primary care studies using this recruitment method also had the highest multimorbidity prevalence.12–14 In addition, this kind of recruitment is likely to produce smaller sample sizes, reducing the precision of estimates.

Differing methods may also partly explain the differences we observed in prevalence estimates. This influence can be inferred from the results of one study in the general population involving individuals of the same age-group among whom conditions were assessed using a variety of sources.30 The prevalence estimate based on self-reports and general practitioner reports was lower than that obtained when data were collected from an extensive physical examination (56.5% vs 71.8%). One study in primary care extracted data from the combined input of general practitioners (using their knowledge of patients), patient self-reports, and medical records.12 This approach should provide more reliable estimates than those based on only a single source of information.

One study estimated the prevalence in the general population based on a pharmacy database.23 This method works better for chronic diseases treated with drugs that are specific to the disease and are taken continuously; however, its main drawback is the lack of definitive diagnostic information.

Prevalence estimates seemed to be greatly influenced by the operational definition of multimorbidity, which has 2 components: the list of diagnoses considered and the cutoff used to define presence of the diagnosis. As an example, the study in our review with the fewest diagnoses considered (5 diagnoses) reported the lowest prevalence values in primary care (0.3% at age 32.5 years and 3.5% at age 75 years) despite its very large size (23,534 patients).15 Other studies from the same country (the Netherlands) that considered more diagnoses reported higher prevalence estimates.1,2,30 This pattern is consistent with a previous report that found large differences in prevalence estimates according to the number of chronic diseases considered.9

Similarly, Figure 4 includes 2 studies of the general population of Canada, using comparable methods. The study of Rapoport et al,25 with 22 diseases taken into consideration, reported a higher prevalence than the study of Cazale and Dumitru,28 with just 7 diseases.

Studies done in both primary care and the general population showed an S-shaped curve for prevalence by age, with low estimates before the age of 40 years and then a steep increase in prevalence followed by a plateau at about the age of 70 years (Figures 2 and 4). This plateau may be due to a balance between new cases and mortality at older ages, or to the current definition of multimorbidity as 2 or more chronic conditions. The plateau at older ages is not as flat when the definition of 3 or more chronic conditions is used (Figure 3).

Suggestions for Study Conduct

Considering all of the various aspects of prevalence studies on multimorbidity highlighted in this systematic review, we suggest some methodologic issues to be considered in the conduct of such studies.

Sampling Method

At the primary care level, there are basically 2 approaches for sampling. One approach is to extract data from existing databases, which usually provides information on the whole practice or a large number of patients, and reflects the general situation prevailing in the setting. Data could be extracted for randomly selected patients or for all patients. The second approach is to include patients seen during clinical sessions within a time period. This method may oversample complex patients with several diseases or frequent attendees; however, it provides insight into the physician’s daily work. Use of one sampling frame or the other is dictated by the research question and the resources available. In studies involving the general population, random samples, either at a national level or in particular geographic locations, are appropriate.

Data Collection

The method most often used for data collection in prevalence studies at the practice level was to check patients’ medical history in medical charts or computerized databases. This method has the advantage of being based on written evidence but assumes that the records are complete, which may not always be the case.

Another approach is to obtain data from the combined input of physicians, patient self-reports, and medical records. Intuitively, the use of multiple sources should provide more reliable estimates than a single source and is preferred when feasible. Studies conducted in the general population predominantly used questionnaires. As this method is based on self-report, it may present the disadvantage of assigning equal weight to both major and minor health conditions. The use of this method may be justified when the research question specifically addresses perceived burden or when very large samples are studied, when no other data are available as in many health surveys. In some studies in the general population, data were obtained from more than 1 source (self-report, medical history from general practitioners, clinical assessment). Again, a multisource method is preferable to a single-source method.

Operational Definition

The list of conditions assessed seems to be the most critical issue in studying prevalence estimates. Our review suggests that considering 4 to 7 diagnoses would lead to an underestimation of the prevalence of multimorbidity. In studies that considered 12 or more diagnoses, we did not observe much variation. We therefore suggest using a list of at least 12 chronic diseases. Further research is needed to select which specific diseases, but a list of the 12 most prevalent chronic diseases with a high impact or burden in a given population would be a good compromise. We cannot provide a precise list from this review.

Tabulation of the number of domains of the CIRS affected by chronic diseases is another method of measuring multimorbidity prevalence comparable to the simple count of diseases.12 This approach deserves further attention as it may simplify coding and data collection.

Concerning the cutoff in number of medical conditions, we found that studies generally reported main results based on a count of 2 or more conditions, but some also reported the number of patients with higher counts. We suggest systematic use of at least 2 operational definitions of multimorbidity, namely, both 2 or more diagnoses (or CIRS domains) and 3 or more diagnoses (or CIRS domains). The latter definition results in a lower prevalence of multimorbidity and likely better identifies patients with higher needs, and thus may be more meaningful for clinicians than a count of 2 or more, which is less discriminating. In addition, the difference in the S-shape pattern between Figures 2 and 3 may further support this new operational definition. Additional research is needed to test this definition.

Reporting Results

When reporting prevalence estimates by age-group, as there is no standard for age-groups, investigators should be sure to provide enough information to allow good assessment of their cohorts in terms of age, especially when they use open-ended age-groups (eg, aged ≥65 years). Information about the age structure (or at least the mean and SD) would facilitate graphical display and comparison. Reporting results both for each sex and for the sexes combined would also facilitate comparison.

Study Limitations

A limitation of any systematic review is the potential omission of relevant articles. Although we tried to use exhaustive inclusion criteria, it is possible that we did not identify all publications on the subject. Our search strategy was based on MeSH and key words assigned by authors, and we may have missed publications that were not indexed under these terms, although we tried to identify further articles through reference lists. Our search strategy had the advantage of using 2 large databases, however, enabling an exhaustive literature review.

Conclusion

In conclusion, in this review of 21 studies, we observed marked differences across studies in the estimated prevalence of multimorbidity. These differences appeared to be largely due to variations in study methodology, especially how multimorbidity was defined. Investigators designing future studies to assess the prevalence of multimorbidity should consider the number of diagnoses to be assessed (with ≥12 frequent diagnoses of chronic diseases appearing ideal) and should attempt to report results for differing definitions of multimorbidity (both ≥3 diseases and the classic ≥2 diseases). Use of a more uniform methodology should permit more accurate estimation of the prevalence of multimorbidity and facilitate comparisons across settings and populations.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Elizabeth Bayliss, MD, MSPH, for her contribution in reading and commenting on the manuscript. We also thank Susie Bernier and Tarek Bouhali for their editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: Dr Fortin is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and partners (CIHR Applied Health Services and Policy Research Chair on Chronic Diseases in Primary Care/Canadian Institutes of Health Research-Institute of Health Services and Policy Research, Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, and Centre de santé et de services sociaux de Chicoutimi). Dr Stewart is funded by the Dr Brian W. Gilbert Canada Research Chair.

Disclaimer: None of the funding agencies had any role in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1.van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Metsemakers JF, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Multimorbidity in general practice: prevalence, incidence, and determinants of co-occurring chronic and recurrent diseases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51(5):367–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in primary care: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14 (Suppl 1):28–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B. Global health, equity, and primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(6):511–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Listening for Direction. A National Consultation on Health Services and Policy Issues. 2007. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/20461.html Accessed Jun 10, 2011

- 5.Valderas JM, Starfield B, Roland M. Multimorbidity’s many challenges: a research priority in the UK [comment]. BMJ. 2007;334 (7604):1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortin M, Soubhi H, Hudon C, Bayliss EA, van den Akker M. Multimorbidity’s many challenges. BMJ. 2007;334(7602):1016–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenberg NE, Kim H, Edwards W, Fleming ST. Burden of common multiple-morbidity constellations on out-of-pocket medical expenditures among older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):423–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starfield B. Challenges to primary care from co- and multi-morbidity. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2011;12(1):1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortin M, Hudon C, Haggerty J, Akker M, Almirall J. Prevalence estimates of multimorbidity: a comparative study of two sources. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):800–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. ; STROBE Initiative Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):805–835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britt HC, Harrison CM, Miller GC, Knox SA. Prevalence and patterns of multimorbidity in Australia. Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Lapointe L. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):223–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kadam UT, Croft PRNorth Staffordshire GP Consortium Group Clinical multimorbidity and physical function in older adults: a record and health status linkage study in general practice. Fam Pract. 2007;24(5):412–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schellevis FG, van der Velden J, van de Lisdonk E, van Eijk JT, van Weel C. Comorbidity of chronic diseases in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(5):469–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macleod U, Mitchell E, Black M, Spence G. Comorbidity and socioeconomic deprivation: an observational study of the prevalence of comorbidity in general practice. Eur J Gen Pract. 2004;10(1):24–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minas M, Koukosias N, Zintzaras E, Kostikas K, Gourgoulianis KI. Prevalence of chronic diseases and morbidity in primary health care in central Greece: an epidemiological study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loza E, Jover JA, Rodriguez L, Carmona L; EPISER Study Group Multimorbidity: prevalence, effect on quality of life and daily functioning, and variation of this effect when one condition is a rheumatic disease. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2009;38(4):312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marengoni A, Winblad B, Karp A, Fratiglioni L. Prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity among the elderly population in Sweden. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1198–1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menotti A, Mulder I, Nissinen A, Giampaoli S, Feskens EJ, Kromhout D. Prevalence of morbidity and multimorbidity in elderly male populations and their impact on 10-year all-cause mortality: the FINE study (Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Elderly). J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):680–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagel G, Peter R, Braig S, Hermann S, Rohrmann S, Linseisen J. The impact of education on risk factors and the occurrence of multi-morbidity in the EPIC-Heidelberg cohort. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8:384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung HY. Persons with chronic conditions. Their prevalence and costs. JAMA. 1996;276(18):1473–1479 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naughton C, Bennett K, Feely J. Prevalence of chronic disease in the elderly based on a national pharmacy claims database. Age Ageing. 2006;35(6):633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newacheck PW, McManus MA, Fox HB. Prevalence and impact of chronic illness among adolescents. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145(12): 1367–1373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapoport J, Jacobs P, Bell NR, Klarenbach S. Refining the measurement of the economic burden of chronic diseases in Canada. Chronic Dis Can. 2004;25(1):13–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuchs Z, Blumstein T, Novikov I, et al. Morbidity, comorbidity, and their association with disability among community-dwelling oldest-old in Israel. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53(6):M447–M455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verbrugge LM, Lepkowski JM, Imanaka Y. Comorbidity and its impact on disability. Milbank Q. 1989;67(3–4):450–484 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cazale L, Dumitru V. Chronic diseases in Quebec: some striking facts [in French]. Zoom Santé. 2008;March:1–4 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Partnership for Solutions Chronic Conditions: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University; 2004. http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org/ Accessed Nov 12, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schram MT, Frijters D, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. Setting and registry characteristics affect the prevalence and nature of multimorbidity in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(11):1104–1112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]