Abstract

Health care reform will add millions of Americans to the ranks of the insured; however, their access to health care is threatened by a deep decline in the production of primary care physicians. Poorer access to primary care risks poorer health outcomes and higher costs. Meeting this increased demand requires a major investment in primary care training. Title VII, Section 747 of the Public Health Service Act previously supported the growth of the health care workforce but has been severely cut over the past 2 decades. New and expanded Title VII initiatives are required to increase the production of primary care physicians; establish high-functioning academic, community-based training practices; increase the supply of well-trained primary care faculty; foster innovation and rigorous evaluation of these programs; and ultimately to improve the responsiveness of teaching hospitals to community needs. To accomplish these goals, Congress should act on the Council on Graduate Medical Education’s recommendation to increase funding for Title VII, Section 747 roughly 14-fold to $560 million annually. This amount represents a small investment in light of the billions that Medicare currently spends to support graduate medical education, and both should be held to account for meeting physician workforce needs. Expansion of Title VII, Section 747 with the goal of improving access to primary care would be an important part of a needed, broader effort to counter the decline of primary care. Failure to launch such a national primary care workforce revitalization program will put the health and economic viability of our nation at risk.

Keywords: education, medical, primary health care, health policy

INTRODUCTION

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L.111–1148) (ACA) will provide health care coverage to nearly all Americans, but it did not go far enough to assure access to appropriate care. Despite providing for expansion of community health centers and the National Health Service Corps, the ACA did not do enough to reverse a serious decline in production of primary care workforce. Cautionary evidence to support this concern comes from the universal health care initiative in Massachusetts, where, despite having one of the nation’s highest ratios of primary care physicians to the resident population, the newly insured were generally unable to access primary care physicians.1 The ACA contained some important provisions to shore up primary care, including primary care incentive payments, a preference for primary care if unfilled residency positions are redistributed, authorization and funding for Teaching Health Centers, extension of Medicare Graduate Medical Education (GME) payments for training in nonhospital settings, and increase in Medicaid rates to 100% of Medicare for primary care physicians. Since passage of the ACA, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) also made a 5-year investment of $168 million to expand primary care physician positions.2,3 All these initiatives are useful, but health care reform demands a much larger and more focused policy effort to produce a greater number of primary care physicians and to distribute these physicians more equitably.

We describe the emaciation of primary care physician production and its adverse consequences for the health of the nation. We review some of the reasons for the limited trainee interest in becoming primary care physicians, who practice longitudinal, comprehensive primary care. As a ray of hope, we present evidence from remarkable successes of HRSA’s Title VII program initiatives in previous decades to address physician workforce deficiencies, including primary care. We amplify recommendations of federal advisory committees to expand the Title VII, Section 747 program to help stimulate the renewal of primary care training. This discussion is intended to mobilize the primary care community and other stakeholders who recognize the value of improving access to physicians trained to work with teams in improved models of care. Title VII could again be the platform for revitalizing primary care.

VALUE OF PRIMARY CARE AND CURRENT DECLINE IN THE UNITED STATES

The evidence that primary care can improve health outcomes and control costs has been well documented by studies conducted over several decades.4–6 Because of universal access to primary care, other industrialized nations enjoy better health status and outcomes than in the United States, despite our significantly greater health care expenditures.7 This difference is partly explained by the higher proportions of primary care physicians within the physician workforce of most other developed nations.

Our nation’s crumbling primary care infrastructure stands in marked contrast to these other nations.6,8,9 Currently, 31% of US physicians practice in primary care specialties, but less than 25% of physicians-in-training are currently entering primary care practice.10,11 Many trainees who do not subspecialize but remain in primary care are electing to practice only in the inpatient setting, reflecting in part the predominant focus on inpatient training at all levels of medical training. Currently 20% of general internists care only for inpatients, and one-third of the trainees entering general internal medicine plan to restrict their practice to inpatient settings.12 The Council on Graduate Medical Education (COGME) recently sounded an alarm that the numbers of primary care trainees and those in the current workforce will likely continue to decline, a situation that must be remedied.13

ECONOMICS ARE RESHAPING THE EDUCATIONAL LANDSCAPE

There are several reasons for the decline in primary care physician production, many of which have to do with artificial market incentives biased against generalist training.14 Choosing primary care rather than a nonprimary care specialty is the equivalent of giving up $3.5 million in career earnings, a difference that decreases the likelihood of choosing a primary care career by nearly one-half.15,16 These economic factors are also associated with reduction in GME training positions for primary care compared with the substantial expansion of nonprimary care training positions by teaching hospitals.10,13,17 For example, between 1998 and 2008, family medicine lost 46 programs and 390 positions, and general internal medicine experienced a loss of nearly 900 general internal medicine positions, while 133 new internal medicine subspecialty programs were created.11 This trend reflects hospital incentives to use GME to support more lucrative hospital services at the expense of producing generalist physicians.

This dire situation has galvanized leading foundations, health policy experts, federal and state health care agencies, and advisory panels to suggest possible solutions. Many recommendations target the payment gap, but others have focused on education payment policy. In 2008, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (Medpac), a federal advisory committee that makes recommendations about Medicare payments, recently decried the primary care income gap and limited community-based training opportunities.18 Medpac’s recommendations were eerily reminiscent of recommendations made by the Institute of Medicine 2 decades earlier.19 COGME similarly warned Congress and the Administration that too little of the nearly $10 billion in Medicare GME funding was going to training physicians in ambulatory primary care.13 In 2010, Medpac went even further, recommending that one-third of GME funding be redirected to training more primary care physicians and other physician specialties in limited supply.20

Revising payment policy for clinical care and GME are possibly the 2 most potent policy options to reform production of primary care physicians. They are also the most politically charged. So, in this article, we focus on a smaller, but strategic, source of investment in health workforce training most often referred to as Title VII.

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INVESTMENT IN PRIMARY CARE TRAINING

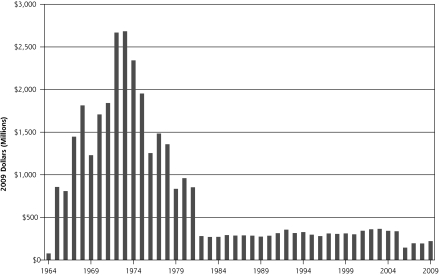

The Title VII program of the US Public Health Service Act is currently focused on supporting primary care educational programs that promote interprofessional education, training to meet needs of a diverse population, and increased diversity in the workforce. This focus is the third strategic modification made by Congress in the last 4 decades.21 At its inception, Title VII provided the equivalent of $2.5 billion (current dollars) to build new medical schools and successfully increased allopathic training by 60% (40 new schools), osteopathic by 83%, and dental programs by 44% (Figure 1).21,22 With the second phase, from 1976 to 1991, through its Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry (Section 747) appropriations, Title VII focused on the growth of our nation’s primary care workforce through new training programs in family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, and geriatrics. This phase of the Title VII, Section 747 initiative played a major role in developing an educational infrastructure to produce primary care clinicians.

Figure 1.

Title VII funding levels, adjusted to 2008 dollars.

Reprinted with permission from Fitzhugh Mullan. Data source: Health Resources and Services Administration.22

Funding for Title VII, Section 747 has declined dramatically during the past 2 decades as its mission was restricted. In 2009, Section 747 received just $48.4 million.23 These cuts occurred despite evidence of the positive effects of exposing trainees to Section 747 programs for increasing choice of primary care careers.24,25 As noted by the 7th Report of Advisory Committee on Training in Primary Care Medicine and Dentistry (ACTPCMD), the committee of experts charged with advising Congress about Title VII Section 747, this accomplishment is all the more remarkable given substantial funding reductions.

RECOMMENDATIONS TO EXPAND THE TITLE VII, SECTION 747 PROGRAM

The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation and COGME both recently called for strategic expansion of Title VII (Table 1).9,13,26 The Macy Foundation did not mention a specific amount, but COGME has recommended an investment increase to $560 million annually, which in current dollars is actually less than one-fourth of Title VII funding in the early 1970s. This 10-fold increase in current Title VII funding would raise it to a little less than 5% of what is currently spent on GME. COGME’s recommendation would support key initiatives that will complement the new ACA investments in primary care training.2,3 COGME’s recommendation did not have specific funding targets, but throughout the report it mentions several goals: funding specifically for community-based training; producing a physician workforce that is 40% primary care; promoting primary care GME training initiatives to enhance the quality and number of physicians; and enhancing student exposure to underserved areas.

Table 1.

Strategic Title VII Expansion for Support of Health Reform

| Specific Area of Strategic Funding | Annual Funding Level | Focus Within Strategic Funding Area |

|---|---|---|

| Investment in community-based training and longitudinal experiencesa | $200 million | Residency position creation and maintenance, 2000 residency positions in community-based sites and Teaching Health Centers |

| $100 million | Expansion of undergraduate medical education training to create longitudinal experiences, financially support those relationships in the community, and create school-based or AHEC resources to support them | |

| $30 million | Support for Rural Training Tracks; undergraduate and graduate level | |

| Expand primary care faculty | $50.5 million | 50 faculty development fellowships annually ($200,000 each to offset salary, benefits, fellowship support, travel), support for a full FTE faculty position at each medical school (150 schools, $270,000 salary, benefits, overhead) |

| Establish high-functioning academic ambulatory practice models for training | $100 million | $500,000 in ongoing support, 200 sites; to support infrastructure and team-based training |

| Reconnect training hospitals to their communities | $50 million | Grants to involve trainees and faculty in community evaluation, description, priority-setting, intervention, and evaluation |

| Innovation grants | $25 million | 10–20 grants annually to test new models of training, population management, and community engagement; support rigorous evaluation |

| Evaluation, analysis, data management | $4.5 million | Funding for evaluation and analysis of Title VII outcomes, data platforms to support impact assessments, and accountable transparency |

| Total | $560 million |

AHEC = Area for Health Education Center; FTE = full-time equivalent.

The primary care residency expansion program requires about $50,000,000 annually to maintain at current levels; likewise, the Teaching Health Center Program requires about $50,000,000 annually to maintain at current levels. This estimate seeks to double the expansion.

We build on COGME’s recommendation of $560 million, offering how this could be allocated to distinct areas where the funds should be expended and some rough estimates for allocating funding (Figure 1). The first focus for funding would be longitudinal, outpatient training experiences at the undergraduate and graduate level. This funding could create 2,000 new primary care residency training positions to replace the 1,200 primary care training positions lost in recent years and create the added capacity sought by the ACA (roughly, $200 million, annually). These funds and related positions should strategically focus on underserved and rural communities by supplementing existing residency programs that serve these populations, by building on the new Teaching Health Center authorization, and by creating community partnerships for longitudinal training opportunities in other underserved/rural sites.

New money is also needed to support existing Rural Training Tracks and build new ones (an additional $30 million per year) and to support partnerships with Critical Access Hospitals. Rural practice experiences for medical students and residents attract a disproportionally large share of graduates into rural practice; unfortunately, many rural residency programs have been lost over the last two decades.27

Medical students would further benefit from more community-based, longitudinal experiences, such as those facilitated by Area Health Education Centers, particularly if they involve community-oriented primary care principles ($100 million per year). We support COGME’s recommendation for community-based primary care practices to enhance the training experience, recognizing that infrastructure development will be an enticement for ambulatory care practices to open their doors to trainees.

Preparing the next generation of physicians to work in new models of practice can be promoted by establishing high-functioning academic ambulatory practice models as an attractive training environment. An annual appropriation of $100 million would provide grants of $500,000 per year to 200 sites to transform practices into team-based medical homes, develop curricular innovations to prepare trainees to deliver evidence-based medicine in these collaborative settings, train faculty to educate trainees in these novel forms of care, and free faculty to dedicate more time to training young physicians. Training programs with high-functioning primary care practices can serve as models for other regional providers and can form clinical and curricular learning collaboratives. This regional learning-by-example follows the successful model of regional GP Super Clinics in Australia.28

Second, Title VII, Section 747 should provide enhanced support for the educators who will train this primary care physician workforce ($50.5 million per year). In the ACTPCMD 7th report, specific recommendations were made to increase fellowship training opportunities for primary care physician-educators to meet greatly expanded educational demands and to create capacity for training to new models of care. These funds could also support training of physician-scientists who are able to lead community-based participatory research, community engagement, and evaluation efforts.

Primary care transformation would benefit from grants to help the third area for new support: grants to help up to 200 training centers implement infrastructure and training capacity for new models of care, such as the patient-centered medical home, and team-based care. The ACA expands demonstration opportunity for the patient-centered medical home, an important transformation of primary care practice, and Title VII should play a major role in facilitating this transformation and preparing the next generation of primary care physicians for this new care model.

Fourth, models, such as New Mexico’s Health Education Rural Outreach (HERO) program, are showing how academic health center-community partnership around training and community engagement can strategically improve health and health access ($50 million, annually).29 This funding would support strategic training partnerships that help draw health professions students from underserved areas and return them there for portions of their training to build and reinforce relationships that help them choose to return home for their careers. The other aspect of this funding would support trainee participation in community-oriented primary care projects to include community definition, characterization, engagement, intervention, and evaluation.

The fifth and sixth foci for enhanced Title VII funding would directly invest two important and often neglected efforts: innovation and evaluation. We propose creation of a small fund to support training innovation experiments ($25 million, annually), and funding for prospective evaluation of Title VII-funded programs ($4.5 million, annually). The latter would improve accountability and effectiveness of this strategic expansion of Title VII.

In summary, the ACA opens the door to the health care system for millions of uninsured individuals. Providing health care coverage to all Americans is an essential prerequisite to raising the standard of health, but the current, rapid decline in the supply of primary care physicians means that many Americans will not be able to benefit from receiving coordinated, continuous, and comprehensive health care. Title VII, Section 747 should reprise its role as a catalyst for increasing our nation’s health workforce. Raising Title VII, Section 747’s investments in primary care training from 0.5% to 5% of what is currently spent on GME could spark a primary care resurgence by building the educational infrastructure and expanding community-based and primary care training for medical students and residents. Historically, such expansions in Title VII funding have been approved by Congress when it appreciates the need for this investment. Many national advisory bodies, including COGME, ACTPCMD, and Medpac, are speaking out to help Congress and other national stakeholders understand that the time has come for such an investment in the primary care work-force. This money should come with a requirement for evaluation and accountability, at least as rigorous as what is implemented for Medicare GME funding. It is time for Title VII, especially Section 747, and for HRSA to be regarded as a centerpiece of a national initiative to train and retain more primary care physicians in longitudinal ambulatory care settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Kathleen Klink for her contributions to early drafts of this paper, and Barbara J. Culliton for her assistance with manuscript editing.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: Dr Phillips was named in a Title VII grant from Georgetown University, Washington, DC, for a shared health policy fellowship. Dr Turner is under contract with Aetna to evaluate quality of care in persons treated with long-term opioids; Director of Health Outcomes Research, University Health System in San Antonio (a safety-net health care institution); and former Executive Deputy Editor, Annals of Internal Medicine.

Funding support: Dr. Turner is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers: Disparities Research for Change.

Disclaimer: The information and opinions contained in manuscript do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the American Academy of Family Physicians, The Council on Graduation Medical Education, the Advisory Committee on Primary Care Training in Medicine and Dentistry, or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Finding Answers Program (Dr Turner support).

References

- 1.Ku L, Jones E, Finnegan B, Shin P, Rosenbaum S. How is the primary care safety net faring in Massachusetts? Community health centers in the midst of health reform. Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Health Resources and Services Administration Primary Care Residency Expansion. HRSA-10-277. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/grants/affordablecareact.html Accessed Jul 11, 2011

- 3.Health Resources and Services Administration Affordable Care Act (ACA) Teaching Health Center (THC) Graduate Medical Education (GME) Payment Program. http://www.hrsa.gov/grants/apply/assistance/teachinghealthcenters/ 2011; Accessed Jul 11, 2011

- 4.Steinwald AB. Primary Care Professionals: Recent Supply Trends, Projections, and Valuation of Services. United States Government Accountability Office, a testimony before the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, US Senate. GAO-08-472T February 12, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Jan-Jun;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-184–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis K, Schoen C, Schoenbaum SC, et al. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International Update on the Comparative Performance of American Health Care. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips RL, Jr, Bazemore AW. Primary care and why it matters for U.S. health system reform. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):806–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garr D. Developing a Strong Primary Care Workforce (Meeting summary). New York, NY: Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salsberg E, Rockey PH, Rivers KL, Brotherton SE, Jackson GR. US residency training before and after the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. JAMA. 2008;300(10):1174–1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weida NA, Phillips RLJ, Jr, Bazemore AW. Does graduate medical education also follow green? Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(4):389–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sprague L. The hospitalist: better value in inpatient care? Issue Brief Natl Health Policy Forum. 2011;March 30;(842):1–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council on Graduate Medical Education Twentieth Report: Advancing Primary Care. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bodenheimer T, Berenson RA, Rudolf P. The primary care-specialty income gap: why it matters. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(4):301–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips RL, Dodoo MS, Petterson S, et al. Specialty and Geographic Distribution of the Physician Workforce: What Influences Medical Student and Resident Choices? Washington DC: The Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation and The Robert Graham Center; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmeri M, Pipas C, Wadsworth E, Zubkoff M. Economic impact of a primary care career: a harsh reality for medical students and the nation. Acad Med. 2010;85(11):1692–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinbrook R. Medical student debt—is there a limit? N Engl J Med. 2008;359(25):2629–2632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Promoting the Use of Primary Care. Report to Congress: Reforming the Delivery System. Washington, DC: Medpac; 2008:23–51 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Institute of Medicine Committee to Study Strategies for Supporting Graduate Medical Education for Primary Care Physicians in Ambulatory Settings Primary Care Physicians: Financing Their Graduate Medical Education in Ambulatory Settings. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission Graduate Medical Education Financing: Focusing on Educational Priorities. Report to the Congress: Aligning Incentives in Medicare. Washington, DC: MedPAC; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reynolds PP. A legislative history of federal assistance for health professions training in primary care medicine and dentistry in the United States, 1963–2008. Acad Med. 2008;83(11):1004–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullan F. Testimony before the House Committee on Education and Labor on the Tri-Committee Draft Proposal for Health Care Reform. June 23, 2009. http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-111hhrg50479/pdf/CHRG-111hhrg50479.pdf Accessed Oct 17, 2011

- 23.Health Professions and Nursing Coalition Updated Title VII and Title VIII Funding Chart. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rittenhouse DR, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, et al. Impact of Title VII training programs on community health center staffing and national health service corps participation. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(5):397–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fryer GE, Jr, Meyers DS, Krol DM, et al. The association of Title VII funding to departments of family medicine with choice of physician specialty and practice location. Fam Med. 2002;34(6):436–440 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Council on Graduate Medical Education NIneteenth Report: Enhancing Flexibility in Medical Education. Rockville, MD: COGME; 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Institute of Medicine Human Resources. Quality Through Collaboration: The Future of Rural Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy of Science; 2005:79–119 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Australian Department of Health and Aging About the GP Super Clinics Program. 2011. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/pacd-gpsuperclinic-about Accessed Oct 22, 2011

- 29.Kaufman A, Powell W, Alfero C, et al. Health extension in new Mexico: an academic health center and the social determinants of disease. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(1):73–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]