Abstract

Objective

Test the hypothesis that autoimmunity induced by inhalation of aerosolized brain tissue caused outbreaks of sensory-predominant polyradiculoneuropathy among swine abattoir employees in Midwestern USA

Methods

Mice were exposed intranasally, 5 days weekly, to liquefied brain tissue. Serum from exposed mice, patients and unaffected abattoir employees were analyzed for clinically pertinent neural autoantibodies.

Results

Patients, coworkers and mice exposed to liquefied brain tissue had an autoantibody profile dominated by neural cation channel IgGs. The most compelling link between patients and exposed mice was MRI evidence of grossly swollen spinal nerve roots. Autoantibody responses in patients and mice were dose-dependent and declined after antigen exposure ceased. Autoantibodies detected most frequently, and at high levels, bound to detergent-solubilized macromolecular complexes containing neuronal voltage-gated potassium channels ligated with a high affinity Kv1 channel antagonist, 125I-α-dendrotoxin. Exposed mice exhibited a behavioral phenotype consistent with potassium channel dysfunction recognized in drosophila with mutant (“shaker”) channels: reduced sensitivity to isoflurane-induced anesthesia. Pathological and electrophysiological findings in patients supported peripheral nerve hyperexcitability over destructive axonal loss. The pain-predominant symptoms were consistent with sensory nerve hyperexcitability

Interpretation

Our observations establish that inhaled neural antigens readily induce neurological autoimmunity and identify voltage-gated potassium channel complexes as a major immunogen.

Introduction

Factors initiating neurological autoimmunity are largely unknown apart from disorders induced by medications, such as myasthenia gravis induced by D-penicillamine,1 or encephalomyelo-radiculopathies induced by systemic neoplasms expressing onconeural antigens.2 An outbreak of a multifocal neurological disorder with prominent sensory polyradiculoneuropathy that was recently encountered in 24 swine abattoir workers seen at our institution provided a unique opportunity to investigate aspects of neurological autoimmunity induction in human subjects. The patients were suspected to have been immunized by inhaling neural autoantigens through occupational exposure to aerosolized porcine brain tissue.3 Their multifocal manifestations were reminiscent of both paraneoplastic autoimmune neurological disorders2, 4, 5 and presentations documented historically in recipients of first generation attenuated rabies virus vaccines prepared from mammalian neural tissues.6, 7 We now identify a clinically pertinent profile of autoantigens defined by the patients' serum IgGs, and describe an animal model that replicates the serological and neuroimaging abnormalities documented in the patients. We conclude that an autoantibody arising in this setting, and targeting one or more components of a neuronal Kv1 voltage-gated potassium channel complex (VGKC), may contribute to neurophysiological impairment.

Materials and Methods

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved these studies.

Clinical Materials

Serum samples were available from the 24 patient subjects of the reported occupational outbreak of neurological autoimmunity.3 All were evaluated and treated at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. Control sera were obtained by the Minnesota Department of Health from 85 swine abattoir workers chosen at random from the Austin, MN plant.3 Community controls (178) were recruited from adult residents of Olmsted County, MN.3 Serum samples were coded for blinded investigation.

Indirect Immunofluorescence

The principal substrate was a composite frozen section (12 μm) of mouse cerebellum, gut and kidney.8 Sera were diluted 1:240, and pre-absorbed with bovine liver powder to reduce non-specific autoantibody interference. Bound IgG was visualized using fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc., Birmingham, AL.). Immunostaining patterns were scored independently by two experienced serologists. Positive sera were titrated to determine antibody detection endpoint. Sera (all patients and 10 mice) were tested for IgGs reactive with Lgi1, Caspr2 and ionotropic NMDA receptor (NR1 subunit) by indirect immunofluorescence using kit assays incorporating transfected and control cells, and validated clinically in this laboratory (Euroimmun AG, Lübeck, Germany).

Radioimmunoprecipitation

Autoantibodies reactive with voltage-gated potassium channel complexes (VGKC), voltage-gated calcium channels and GAD65 were quantified by radioimmunoprecipitation assays using clinically validated protocols:9–11 digitonin-solubilized synaptic membrane channel proteins complexed with 125I-labeled ligand (or 125I-human GAD65 antigen [purchased from Kronus, Star, ID]) were held 8 hours at 4°C with serum before adding secondary antibody. Gamma emission, measured from the washed pellet of antibody-antigen complexes precipitated with polyethylene glycol, is recorded as nmoles precipitated per liter of serum. Patient serum VGKC complex-IgG results were concordant in assays using macromolecular complexes solubilized from porcine, rabbit and human brain membranes and labeled with a tracer, 125I-α-dendrotoxin (high affinity ligand for KV1.1, KV1.2 and KV1.6 potassium channels); levels were consistently higher with porcine antigen. Solubilized calcium channels were labeled with 125I-ω-conotoxin GVIA (N-type) or 125I-ω-conotoxin MVIIC (P/Q-type).9 Sera yielding positive results were retested using 125I-ligand alone to verify antigen specificity.12

ELISA

IgGs reactive with myelin basic protein or rat striated muscle antigens were detected by enzyme-linked immunoassay13 with sera diluted in doubling steps, from 1:200. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated secondary antibody was used to detect bound immunoglobulins. OD405 values considered positive exceeded 150% of the mean OD405 value yielded by five normal control sera for each dilution.

Animal Procedures

Fresh porcine brains were homogenized with addition of phosphate buffered saline (2 mL per gram) to reduce homogenate viscosity and allow reproducible dosing of the animals. Homogenate was flash frozen in 1 mL aliquots, and stored at −80°C prior to use. Female 129S6/SvEv mice, purchased from Taconic at age 4–5 weeks, had unrestricted access to food and water, and were acclimated to the research environment for 10 days before use. Groups of 10–12 mice received intranasal instillations once or twice daily, 5 days per week under anesthesia (4% isofluorane/4% O2, Supplemental data). Liquefied brain (20 μL) was placed across the nares of the supine mouse until completely inhaled. Control mice were given PBS once or twice daily by the same method. In the first experiment, a single daily intranasal instillation yielded a low autoantibody response by day 42. We therefore doubled the dose from day 57 by repeating intranasal exposure to liquefied brain or PBS twice daily (interval 6 hours). In the second experiment, mice were exposed twice daily from day 0. In the third experiment, mice were exposed once daily for 28 days and twice daily thereafter. Mice were weighed weekly and examined for signs of neurological impairment.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI studies14, 15 were conducted using Bruker Biospin Avance II 300 MHz and 700 MHz NMR machines with field strengths of 7 and 16.4 Tesla, respectively. Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation. For contrast studies, gadolinium DTPA (Magnevist) was injected into the tail vein (0.2 mL/kg). Mice were placed in a standard small rodent probe, with heads stabilized using a bite bar and nose cone for continuous anesthesia. Respiratory rate was monitored via MRI compatible chest pressure sensors (1025 MRI monitoring and gating system SA Instruments, Inc, Stony Brook, NY). A separate computer continuously monitored the recorded parameters, and adjusted isoflurane anesthesia dose. A separate thermocouple-linked system monitored and adjusted the temperature in the scanner bore using a forced air heating system to maintain a constant ambient temperature. Mice were orientated head up in the vertical bore, to allow comfortable breathing. The following imaging sequences are used: 1) Tripilot 3D RARE sequence in three perpendicular planes to verify animal placement and select appropriate field of view; 2) T1 weighted imaging, using both 3D and 2D Gradient echo based sequences including GEFI, FLASH and spin echo sequences including MSME; 3) T2 weighted imaging, using both 3D and 2D RARE, FISP and MSME sequences; 4) T1 weighted imaging following gadolinium injection, plus Magnetization Transfer pulse for better tissue enhancement visualization. Image visualization and processing were performed using Bruker's Xtip Image software (part of the ParaVision software suite) and by Analyze 9.0, a biomedical image analysis package developed by Mayo Clinic's Biomedical Imaging Resource (BIR).16

Statistical Analyses

We analyzed levels of signature IgG (titer, log2 scale) and VGKC complex-IgG (nmol/L, log10 scale) as continuous variables, and data for coexisting autoantibody numbers as a sum of dichotomous (negative or positive) variables. Median values were used for serum levels of all antibodies for the four groups: patient cases, asymptomatic workplace controls, mice exposed to neural tissue or vehicle. Correlation coefficients and p values were calculated using JMP statistical analysis software.

Results

Neural-specific Signature IgG Immunostaining Pattern

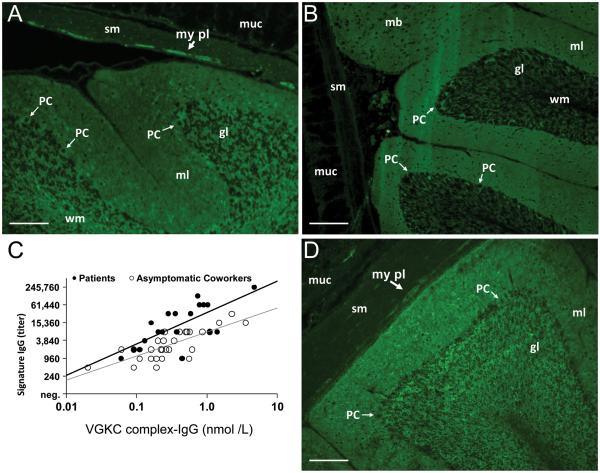

At the initial serological screening assay performed in clinical evaluation, a “signature” IgG autoantibody was recognized and defined by immunofluorescence criteria in all 24 patients' sera.3 Figure 1A illustrates the tissue distribution that is characteristic of the signature IgG pattern on the standard composite tissue substrate. Immunoreactivity is prominent in synapse-rich neuropil, cytoplasm of Purkinje neurons and granular layer neurons and white matter in cerebellar cortex, and enteric neurons and nerve twigs in gut smooth muscle. Mucosa and smooth muscle are not reactive. One-third of asymptomatic coworkers' sera (34%) yielded the same immunostaining pattern, but at lower median titer (Table 1). The initial publication describing this outbreak reported myelin basic protein as a defined antigen contributing to the staining pattern in white matter and extending into the granular layer.3 The signature IgG pattern was consistent with a complex combination of multiple co-existing neural cytoplasmic and synaptic autoantibodies, as has been documented in the context of paraneoplastic and idiopathic neurological disorders in this laboratory in the past decade of clinical interpretive service activities. 4, 8, 17, 18 Here we now report the clinically pertinent neural autoantibodies identified to date in the serum of these patients.

FIGURE 1.

Serum IgGs reactive with antigens in central and peripheral neural tissues detected by indirect immunofluorescence on substrates of cerebellar cortex, midbrain and stomach; scale bar: 200 μm. IgG of a patient (A) and a mouse (D) exposed nasopharyngeally to liquefied porcine brain tissues. (A and D) Note prominent synaptic staining in molecular layer (ml) of cerebellar cortex. Somata and processes of neural cells also are immunoreactive in the molecular layer and granular layer (gl), and enteric neurons and nerve fibers in the myenteric plexus (my pl); gut smooth muscle (sm) and mucosa (muc) are not immunoreactive. (B) IgG in serum of a control patient with idiopathic VGKC complex-IgG autoimmunity yields similar synaptic staining in the cerebellar molecular layer (and midbrain) but, in contrast to the “Signature IgG” pattern yielded by serum of aerosol –exposed patients and mice, this IgG does not bind to neuronal somata and processes; (C) IgG titers in the aerosol-exposed patients' sera correlated significantly with levels of VGKC complex-IgG (patients, dark line, R = 0.67, p < 0.01; asymptomatic coworkers, gray line, R = 0.73, p < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Serum Autoantibody Profiles of Patients, Co-workers and Mice Exposed to Liquefied Brain Tissue by Oro-nasopharyngeal Routea

| Autoantibody | Patients (n=24) | Coworkers (n=85)b | Mice (n=34) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Median Value (range) | Frequency | Median Value (range) | Frequency | Median (range) | |

| Immunofluorescence signature IgG pattern | 24 (100%) | 7,860c (240 – 245,760) | 29 (34%) | 1,920c (240 – 30,720) | 34 (100%) | 30,720c (7680 – 61,440) |

| VGKC complexd | 19 (79%) | 0.37 nmol/L (0.06 – 4.70) | 44 (52%) | 0.23 nmol/L (0.06 – 3.6) | 34 (100%) | 2.11 nmol/L (0.02 – 22) |

| Myelin basic protein | 18 (75%) | 6,400c (200 – 51,200) | 28 (33%) | 12,800c (200 – 51,200) | 34 (100%) | 25,600c (800 – 409,600) |

| Voltage-gated calcium channels: | ||||||

| - P/Q-type | 7 (29%) | 0.09 nmol/L (0.07 – 0.51) | 19 (22%) | 0.05 nmol/L (0.03 – 0.24) | 31 (91%) | 0.11 nmol/L (0.02 – 0.31) |

| -N-type | 6 (25%) | 0.08 nmol/L (0.05 – 0.46) | 14 (16%) | 0.09 nmol/L (0.03 – 0.74) | 28 (82%) | 0.12 nmol/L (0.02 – 0.39) |

| Striated muscle | 6 (25%) | 480c (60 – 15,360) | – | – | 25 (72%) | 1,600c (200 – 6,400) |

| GAD65 | 1 (4.2%) | 0.29 nmol/L | – | – | 15 (44%) | 0.15 nmol/L (0.02–0.98) |

The prevalence of these autoantibodies in community adult control subjects (n=178) was <1%, except for GAD65 (2.5% positive). Normal value range for immunoprecipitation assays: 0.00–0.02 nmol/L.

Insufficient serum available to perform all assays.

Units expressed as titer (reciprocal of farthest dilution scored positive); negative values: <120 (signature IgG), <200 (MBP-IgG), <60 (striational Ab, patients) or <200 (striational Abs, mice).

Sera of 2 patients (VGKC complex-IgG values: 0.78 and 0.37 nmol/L) were positive for Caspr2-IgG (tested by transfected cell-binding immunofluorescence assay at 1:20 dilution); none was positive for Lgi1; 1 mouse serum of 10 tested was positive for Caspr2-IgG at 1:40 dilution (VGKC complex-IgG value: 6.39 nmol/L); none was positive for Lgi1-IgG.

Spectrum of Neural-specific IgG Autoantibodies Identified

In the cerebellar molecular layer (and also midbrain, not shown) the diffuse glow yielded by signature IgG binding resembled in part the pattern that we and others have previously shown is characteristic of IgG in serum of patients with spontaneous VGKC complex autoimmunity18 (illustrated for comparison in Figure 1B). We confirmed this suspected specificity by demonstrating IgG binding to neuronal α-dendrotoxin-sensitive (“shaker-type”) Kv1 voltage-gated potassium channel complexes (VGKC complex-IgG) in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay employing detergent-solubilized CNS synaptic proteins ligated with 125I-α-dendrotoxin18. Nineteen of 24 patients' sera (79%) and 43 of 85 asymptomatic coworkers' sera (51%) contained VGKC complex-IgG. The levels of VGKC complex-IgG in the patients' serum correlated directly with the titer of the signature IgG (Fig 1C). No control subject's serum among 178 age-matched local community residents was positive for the signature IgG or VGKC complex-IgG.

VGKC complex-IgG-positive patients' sera were tested additionally by immunofluorescence on HEK-293 cells transgenically expressing proteins known to co-precipitate with solubilized Kv1 VGKCs, namely Lgi1 or Caspr2.19, 20 IgG in 2 of 19 sera (8%) bound to Caspr2; no serum IgG bound to non-transfected cells or to cells expressing Lgi1.

Titers of the signature IgG correlated significantly with the total number and levels of the identified neural-specific autoantibodies of clinical relevance. In descending frequency these were specific for: VGKC, P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels, striated muscle contractile proteins, and N-type voltage-gated calcium channels (Table 1). One patient was positive for GAD65-IgG. IgGs reactive with other central and peripheral nervous system antigens (aquaporin-4, collapsin response-mediator protein [CRMP]-5, amphiphysin, peripherin and NMDA receptors) were sought, but not found. Serum from 11 patients were tested in the Mayo Clinical Immunology Laboratory for GM1 and GD1B ganglioside antibodies; all were negative.

Mice Exposed Intranasally to Liquefied Brain Tissue Produce Neural Autoantibodies

Using the same clinically validated assays employed to test patients' sera, we screened sera from mice exposed 5 days weekly to liquefied brain tissue. All contained IgG that bound selectively to neural elements, in the characteristic pattern of signature IgG (Fig 1E); sera of vehicle-exposed control mice were negative. The signature IgG was first detected at day 14 of exposure. All recipient mice were seropositive after 28 days of twice daily exposure.

The serum of brain tissue-exposed mice contained all neural autoantibodies identified in the patients' sera (Table 1), at frequencies and levels higher than found in the patients. VGKC and myelin basic protein (MBP) autoantibodies, detected most commonly in patients, were found in 100% of mice at levels that rose in parallel with the signature IgG level (Fig 2A). Of 10 tested mouse sera, one was Caspr2-positive and none was Lgi1-positive. Mouse sera were negative for aquaporin-4, CRMP-5, amphiphysin, peripherin and NMDAR antibodies. Interestingly, the neuroendocrine GAD65 autoantibody, which was detected in only one patient, was induced in 44% of mice. No patient or mouse serum contained either of two other pancreatic islet cell-reactive IgGs that serve as markers of type 1 diabetes susceptibility (IA-2 and insulin autoantibodies). Furthermore, no sex and strain-matched control mouse was seropositive for GAD65 autoantibody, including the 20 mice exposed to intranasal vehicle and 10 mice injected repeatedly with recombinant aquaporin-4 and adjuvants by intradermal or intraperitoneal routes. Vehicle-exposed mice produced no neural-reactive IgG.

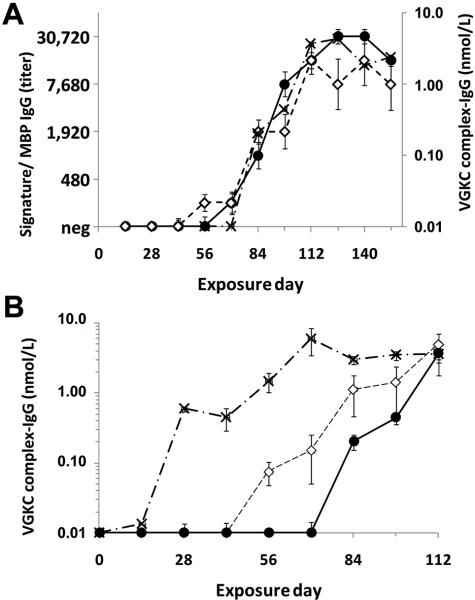

FIGURE 2.

Autoantibody profiles in mice exposed 5 days per week to liquefied brain tissue by oronasopharyngeal exposure. (A) Median serum levels of signature IgG ( ), myelin basic protein (MBP)-IgG (–◇–) and VGKC complex-IgG (–X–) increase in parallel in 10 mice for which exposure frequency was doubled at day 57. (B) Dose-dependent production of VGKC complex-IgG in three groups of 10 mice. Median serum levels rose progressively 28 days after the dose of inhaled brain tissue was doubled (–X– day 0; –◇– day 29;

), myelin basic protein (MBP)-IgG (–◇–) and VGKC complex-IgG (–X–) increase in parallel in 10 mice for which exposure frequency was doubled at day 57. (B) Dose-dependent production of VGKC complex-IgG in three groups of 10 mice. Median serum levels rose progressively 28 days after the dose of inhaled brain tissue was doubled (–X– day 0; –◇– day 29;  day 57).

day 57).

Autoantibody Responses Induced by Inhalation of Liquefied Brain Tissue are Dose-Dependent

In both patients and mice, the serum levels of all autoantibodies correlated with dose of neural antigen exposure. In the patients, serum autoantibody levels correlated with the individual's workstation distance from the point of brain extraction/aerosol emission at the swine abattoir.3 In the mice, levels of VGKC complex-IgG, signature IgG and MBP-IgG rose sharply 28 days after doubling the dosage (Fig 2A and B).

Neurological Resolution Accompanies Spontaneous and Therapy-Induced Reductions in Autoantibody Levels

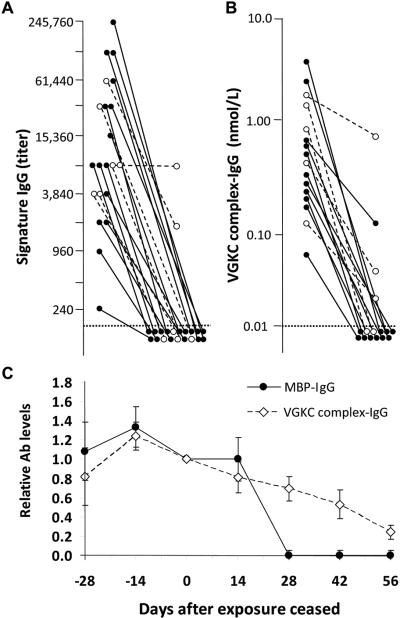

One or more follow-up serum evaluations were available for 21 patients. Signature IgG levels fell below the detection threshold in 19 (90%) at 3–48 months after neural antigen exposure ceased (Fig. 3A). In 4 of 5 patients who did not receive immunotherapy, signature IgG levels fell below detection limits spontaneously (after a mean interval of 16 ± 7.2 months; range, 6.3 – 38). For 16 patients receiving immunotherapy, the mean interval from initial serological analysis to the first negative result was 13 ± 3.5 months (range, 1.4 – 48).

FIGURE 3.

Patients' serum autoantibody levels fell after neural antigen exposure ceased. (A) Signature IgG and (B) VGKC complex-IgG levels. Patients' antibody levels fell, with (●—●) and without (◯—◯) immunotherapy. Horizontal dotted lines indicate detection thresholds. (C) Serum autoantibody levels in mice fell after neural antigen exposure ceased; MBP-IgG ( ) and VGKC complex-IgG (–◇–).

) and VGKC complex-IgG (–◇–).

VGKC complex-IgG levels fell concurrently with the signature IgG. In 12 of 16 patients (75%) VGKC complex-IgG levels fell below the detection threshold by 3-48 months after exposure ceased (Fig 3B). The mean interval from initial serological analysis to the first negative result was 8.5 ± 2.3 months for patients receiving immunotherapy. At last follow up, 3 of 5 patients (60%) who did not receive immunotherapy remained seropositive (after a mean interval of 21 ± 8.3 months after exposure ceased).

Symptoms in most patients resolved slowly. A common lasting complaint was persistent pain, described as aching, burning, stabbing and tingling, and in varied regions (extremities, trunk and, in some patients, whole body). Normalization of motor, sensory and reflex signs was noted at bedside testing; improvement was confirmed by electrophysiological testing. An instructive patient reported improved symptoms over a 24 month period after an initial course of high dose i.v. methylprednisolone followed by maintenance immune globulin infusions, 0.4 g/Kg i.v. (IVIg) at 2–3 week intervals. EMG and nerve conduction abnormalities resolved. During maintenance therapy, serum VGKC complex-IgG levels fell below detection threshold and pain relief allowed discontinuation of narcotic medications. With each attempt to wean IVIg therapy, VGKC complex-IgG reappeared and was accompanied by painful leg cramping and fatigue.

Autoantibody levels peaked earliest in mice exposed early to brain antigens at high dose (Fig 3C). Thereafter, a plateau level was sustained in all mice. Levels fell after intranasal exposure was discontinued (Fig 3A and B). At 2 weeks after exposure ceased, the median VGKC complex-IgG value had fallen by 18%, and at 8 weeks it had fallen by 88%. MBP-IgG was not detectable in any mouse 4 weeks after exposure ceased.

Serological, Clinical and Imaging Correlations in Patients and Mice

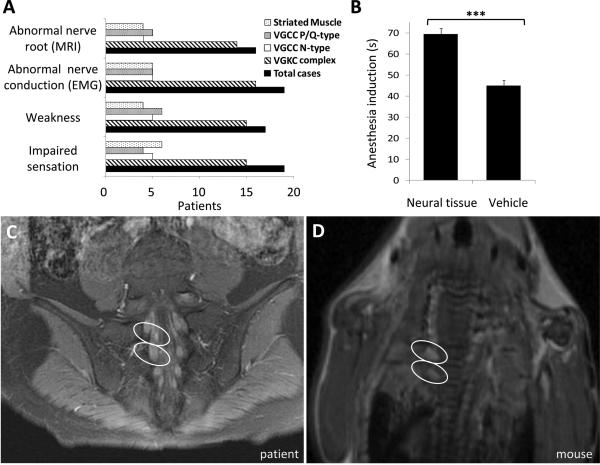

Despite the patients' complaints of severe sensory symptoms (prickling paresthesias [100%], pain [96%] and commonly fatigue), findings on neurological examination were mild.3 Nerve conduction study abnormalities were stereotypical and implied damage at the nerve root level and nerve terminals with little damage in the middle sections of nerves3. Electrophysiological or quantitative sensory testing in 7 of 24 patients (29%) indicated hyperexcitability. Electrophysiological abnormalities included absent distal sensory responses, prolonged distal motor latencies and prolonged f-wave latencies; conduction velocities were normal.3 Nerve pathology showed subtle segmental demyelination and inflammatory cell collections.3 Thus, the combined pathological and physiological findings supported sensory greater than motor involvement, and peripheral nerve hyperexcitability and demyelination rather than destructive axonal loss. VGKC complex-IgG was detected in 15 of 19 patients (79%) with quantitatively documented sensory impairment (Fig 4A), and in 88% of patients with abnormal nerve conduction studies. Clinical examination scores indicated mild or moderate weakness in 17 patients (84% VGKC complex-IgG-positive).

FIGURE 4.

Clinical, behavioral and imaging observations in patients and mice exposed to liquefied brain tissue. (A) Frequency of neural-specific autoantibodies in serum of patients with documented motor, sensory and imaging abnormalities. (B) Sensitivity to isoflurane-induced anesthesia was reduced in mice exposed to liquefied neural tissue (***p < 0.001, n = 30). (C, D) Representative magnetic resonance images of spinal cord revealing nerve root abnormalities (circled) in a patient and a mouse. Images are post-gadolinium T1-weighted coronal scans of sacral (patient) and thoracic (mouse) spinal roots. Nerve root brightness reflects enhanced blood-nerve barrier permeability.

No mouse had overt neurological impairment (grooming, weight gain, strength, coordination, gait, pupillary light reflexes and exploratory activity were normal). However, from day 42 onward a gross behavioral abnormality was noted at daily induction of anesthesia with isoflurane inhalation. Mice exposed to brain tissue exhibited excessive hyperactivity (documented quantitatively, Fig 4B, and by video [Supplemental data]). This unusual behavior persisted for the duration of the study. On average, those mice required 69 ± 2.7 seconds of isoflurane inhalation to achieve anesthesia, while control vehicle-exposed mice required only 45 ± 1.0 seconds (p < 0.001).

Spinal root abnormalities were documented in 72% of patients who were investigated by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)3: ganglionic enlargement, T2 hyperintensity, or gadolinium-enhanced dorsal roots (Fig 4C). Under coded conditions, we evaluated by MRI two control vehicle-exposed mice and four mice that after 84 days of high dose neural antigen exposure had high autoantibody values. T1 weighted images revealed gadolinium-enhanced dorsal roots in all four brain tissue-exposed mice (Fig 4D), but no abnormality in the control mice. Brain, spinal cord and nerve roots were dissected for histopathological evaluation 4 days after imaging. No evidence of inflammation or demyelination was found in any mouse. Abnormalities in biopsied patients' sural nerves were minimal.3

Discussion

The serological findings we report here confirm the autoimmune pathogenesis hypothesized for the occupational outbreak of a neurological disorder with sensory-predominant polyradiculoneuropathy among swine abattoir workers exposed to aerosolized brain tissue.3 The IgG specificities we have identified in the patients' sera indicate that multiple autoantigens served as co-immunogens in eliciting a spectrum of neural-specific autoantibodies. It is conceivable that brain lipids might have provided adjuvant activity. Multiple neural-specific IgGs contributed to the composite signature immunostaining pattern that was documented at initial clinical serological screening3. All of the identified neural-specific IgGs, except for myelin basic protein-IgG, have recognized clinical pertinence in patients with idiopathic and paraneoplastic autoimmune neurological disorders.5, 9, 18, 21

The serum autoantibody profile in mice exposed intranasally to liquefied brain tissue paralleled the profile identified in occupationally-exposed patients and in a majority of asymptomatic co-workers. Neurological symptoms and signs were restricted to abattoir employees who received aerosolized brain tissue in highest dose, i.e., individuals whose work stations were nearest the point of brain liquefaction/aerosol emission.3 The antibody responses in mice were similarly dose-dependent—a single daily dose of aerosol was below the threshold required for autoantibody production but doubling the frequency of exposure exceeded the required threshold. The nerve root MRI abnormalities documented in mice validated the clinical model of autoimmunity induced by intranasal immunization.

VGKC complex-reactive IgGs were the most frequent autoantibody specificity encountered in both humans and mice exposed to liquefied brain tissue, and serum levels were remarkably high (on average 1 log order greater than calcium channel IgG levels). In clinical practice, VGKC complex-IgGs serve as biomarkers for a spectrum of spontaneously acquired central and peripheral nervous system disorders.10, 18, 22, 23 Among 72 patients in whom VGKC complex-IgG was detected incidentally by this laboratory in service serological screening for markers of spontaneous neurological autoimmunity, one in four had somatic peripheral neuropathy.18 It was recently reported that among VGKC autoantibodies identified in a clinical setting by immunoprecipitation assays employing solubilized complexes ligated with 125I-α-dendrotoxin, only 3% or fewer bind to a Kv1 subunit.19, 20 The IgGs detected in patients with autoimmune limbic encephalitis bound to the trans-synaptic protein Lgi1.19, 24 In patients with peripheral nerve hyperexcitability, with and without central nervous system involvement, the identified antigen to which 6 to 20% of detected VGKC complex-IgGs bound was the paranodal protein Caspr2.20, 24 Excluding VGKC complex-IgG-positive patients who have limbic encephalitis, which is strongly associated with Lgi1 specificity,19 the definitive antigenic component in the VGKC complex remains to be identified in a majority of the reported seropositive cases, as is so for the patients and mice of this report.

Motor nerve hyperexcitability, manifest as myokymia, muscle fasciculations, cramps and neuromyotonia, is the peripheral nerve presentation customarily recognized in VGKC complex-IgG-seropositive patients.22, 25 However, sensory nerve hyperexcitability, manifest as paresthesias, also has been reported with VGKC autoimmunity.26, 27 All of the swine abattoir patients reported prickling and tingling paresthesias among their main symptoms. Paresthesia also is frequently reported by patients receiving the VGKC antagonist drug aminopyridine.28, 29 In sum, the observations suggest a relationship between VGKC complex-IgG and the paresthesias experienced by the swine abattoir patients.

IgG-mediated VGKC complex dysfunction plausibly explains the resistance of VGKC complex-IgG-seropositive mice to isoflurane anesthesia. Fruit flies with nonfunctional mutations in KV1-type VGKCs exhibit vigorous leg shaking during induction of anesthesia with isoflurane, with IC50 values more than doubled in Kv1 mutant flies by comparison with wild-type Kv1 flies.30 This phenomenon is the origin of the historical nomenclature “shaker channels” used to describe the VGKC family Kv1.1–Kv1.8.31

Parallels between the clinical syndrome induced by occupational aerosol exposure and our findings in mice immunized by intranasal instillation demonstrate that inhalation of neural antigens readily generates neurological autoimmunity. A subset of the Kv1 VGKC family appears to be particularly immunogenic when administered by this route. We conclude from the presented data that functional impairment of one or more components of VGKC macromolecular complexes in the peripheral or central nervous system is responsible in part for the neurological manifestations induced in both humans and mice. Our findings warrant caution in considering therapeutic trials involving autoantigen administration by the oronasal route as “tolerization” therapy for autoimmune neurological disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christine Hachfeld, Stacy Hall, Vickie Mewhorter, Seth Eisenman, Evelyn Posthumus, Aaron Maixner and Debby Cheung for excellent technical assistance, Dr. Karl Krecke for reviewing the human MRI scans, Jeffrey Gamez for performing mouse MRI scans, Prabin Thapa for statistical analysis, and the Minnesota Department of Health for providing serum samples from asymptomatic swine abattoir workers, and for data concerning distance of seropositive employees' workstation from the point of brain extraction/aerosol emission at the swine abattoir.

This work was funded by the Mayo Foundation and grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK071209 [VAL], NS058698 [IP] and NS065007, NS36797 [CJK]).

Glossary

Non-standard abbreviations used

- VGKC

voltage-gated potassium channel complex

- Caspr2

contactin-associated protein-2

- Lgi1

leucine-rich glioma-inactivated protein-1

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- VGCC

ovltage-gated calcium channel

- GAD-65

glutamic acid decarboxylase

- IA-2

islet cell antigen

- NMDAR

N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bucknall RC, Dixon ASJ, Glick EN, Woodland J, Zutshi DW. Myasthenia gravis associated with penicillamine treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Br Med J. 1975;1:600–602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5958.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lachance DL, Lennon VA. Paraneoplastic neurological autoimmunity. In: Kalman B, Brannagan TH III, editors. Neuroimmunology in Clinical Practice. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2008. pp. 210–217. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachance DH, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, et al. An outbreak of neurological autoimmunity with polyradiculoneuropathy in workers exposed to aerosolised porcine neural tissue: a descriptive study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:55–66. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu Z, Kryzer TJ, Griesmann GE, Kim K, Benarroch EE, Lennon VA. CRMP-5 neuronal autoantibody: marker of lung cancer and thymoma-related autoimmunity. Ann Neurol. 2001;49:146–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pittock SJ, Kryzer TJ, Lennon VA. Paraneoplastic antibodies coexist and predict cancer, not neurological syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:715–719. doi: 10.1002/ana.20269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hemachudha T, Griffin D, Giffels B, Johnson R, Moser A, Phanuphak P. Myelin basic protein as an encephalitogen in encephalomyelitis and polyneuritis following rabies vaccination. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:369–374. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198702123160703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFadzean A, Wong C. Neuroparalytic accidents of rabies vaccination. Bull Hong Kong Chinese Med Assoc. 1952;4:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pittock SJ, Yoshikawa H, Ahlskog JE, et al. Glutamic acid decarboxylase autoimmunity with brainstem, extrapyramidal, and spinal cord dysfunction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1207–1214. doi: 10.4065/81.9.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lennon VA, Kryzer TJ, Griesmann GE, et al. Calcium-channel antibodies in the Lambert-Eaton syndrome and other paraneoplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1467–1474. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vernino S, Lennon VA. Ion channel and striational antibodies define a continuum of autoimmune neuromuscular hyperexcitability. Muscle Nerve. 2002;26:702–707. doi: 10.1002/mus.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walikonis JE, Lennon VA. Radioimmunoassay for glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65) autoantibodies as a diagnostic aid for stiff-man syndrome and a correlate of susceptibility to type 1 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:1161–1166. doi: 10.4065/73.12.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apiwattanakul M, McKeon A, Pittock SJ, Kryzer TJ, Lennon VA. Eliminating false-positive results in serum tests for neuromuscular autoimmunity. Muscle Nerve. 2010;41:702–704. doi: 10.1002/mus.21653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griesmann GE, Kryzer TJ, Lennon VA. Autoantibody Profiles of Myasthenia Gravis and Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome. In: Rose NR, Hamilton RG, Detrick B, editors. Manual of Clinical and Laboratory Immunology. Sixth ed ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2002. pp. 1005–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denic A, Macura SI, Mishra P, Gamez JD, Rodriguez M, Pirko I. MRI in rodent models of brain disorders. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:3–18. doi: 10.1007/s13311-010-0002-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pirko I, Johnson AJ, Chen Y, et al. Brain atrophy correlates with functional outcome in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2011;54:802–806. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robb RA. The biomedical imaging resource at Mayo Clinic. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:854–867. doi: 10.1109/42.952724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernino S, Lennon VA. New Purkinje cell antibody (PCA-2): marker of lung cancer-related neurological autoimmunity. Ann Neurol. 2000;47:297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan KM, Lennon VA, Klein CJ, Boeve BF, Pittock SJ. Clinical spectrum of voltage-gated potassium channel autoimmunity. Neurology. 2008;70:1883–1890. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312275.04260.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai M, Huijbers MG, Lancaster E, et al. Investigation of LGI1 as the antigen in limbic encephalitis previously attributed to potassium channels: a case series. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:776–785. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70137-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irani SR, Alexander S, Waters P, et al. Antibodies to Kv1 potassium channel-complex proteins leucine-rich, glioma inactivated 1 protein and contactin-associated protein-2 in limbic encephalitis, Morvan's syndrome and acquired neuromyotonia. Brain. 2010;133:2734–2748. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKeon A, Lennon VA, Lachance DH, Fealey RD, Pittock SJ. Ganglionic acetylcholine receptor autoantibody: oncological, neurological, and serological accompaniments. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:735–741. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newsom-Davis J, Buckley C, Clover L, et al. Autoimmune disorders of neuronal potassium channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;998:202–210. doi: 10.1196/annals.1254.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thieben MJ, Lennon VA, Boeve BF, Aksamit AJ, Keegan M, Vernino S. Potentially reversible autoimmune limbic encephalitis with neuronal potassium channel antibody. Neurology. 2004;62:1177–1182. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000122648.19196.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancaster E, Huijbers MG, Bar V, et al. Investigations of caspr2, an autoantigen of encephalitis and neuromyotonia. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:303–311. doi: 10.1002/ana.22297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liguori R, Vincent A, Clover L, et al. Morvan's syndrome: peripheral and central nervous system and cardiac involvement with antibodies to voltage-gated potassium channels. Brain. 2001;124:2417–2426. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.12.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ochoa JL, Torebjork HE. Paraesthesiae from ectopic impulse generation in human sensory nerves. Brain. 1980;103:835–853. doi: 10.1093/brain/103.4.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herskovitz S, Song H, Cozien D, Scelsa SN. Sensory symptoms in acquired neuromyotonia. Neurology. 2005;65:1330–1331. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000180688.06885.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kocsis JD, Bowe CM, Waxman SG. Different effects of 4-aminopyridine on sensory and motor fibers: pathogenesis of paresthesias. Neurology. 1986;36:117–120. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bever CT, Jr., Leslie J, Camenga DL, Panitch HS, Johnson KP. Preliminary trial of 3,4-diaminopyridine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:421–427. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tinklenberg JA, Segal IS, Guo TZ, Maze M. Analysis of anesthetic action on the potassium channels of the Shaker mutant of Drosophila. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;625:532–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb33884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papazian DM, Schwarz TL, Tempel BL, Jan YN, Jan LY. Cloning of genomic and complementary DNA from Shaker, a putative potassium channel gene from Drosophila. Science. 1987;237:749–753. doi: 10.1126/science.2441470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.